This story is part of the Grist arts and culture series Remember When, a weeklong exploration of what happened to the climate solutions that once clogged our social feeds.

At Alaska’s northernmost point, a bowhead whale carcass on the beach attracted a visitor: a massive polar bear.

Kiliii Yuyan, a National Geographic photographer, caught a snapshot of the bear while on assignment in Alaska in 2016. He was visiting the Iñupiat as they butchered whales they’d hauled up onto the spring ice. In the image, the bear is looking up at his camera, the fur around its mouth tinted red from blood. Two sideways scars adorn its nose, with a third slash above its right eye raising a large tuft of fur.

“The hunters in particular have a really deep respect for those big-ass, crazy scarred ones,” Yuyan said. “When that bear came down, everyone was like, ‘That one, he’s a survivor. Let him eat. Let him eat!’ Everyone was shouting it.”

It’s different from the polar bear photos that once saturated our media diet. Starting about two decades ago, National Geographic and the like began churning out images of lonely, hungry bears adrift on melting ice floes, painting them as the hapless victims of climate change. Whereas charts and statistics had failed to evince much of a reaction from the public, the polar bear sparked sympathy.

But today, that symbol has largely fallen out of fashion. The advocacy group ClimateXChange even says the focus on the polar bear has done a “disservice” to the goals of the movement; a handbook for public engagement for members of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the world’s leading group of climate experts convened by the United Nations, says the image prompts “cynicism and fatigue.” Overexposure has turned the polar bear into a fluffy, environmental cliche, like saving the whales or hugging trees, as opposed to a real-life carnivore with dangerous teeth and claws.

After so many years of curated photos of perfectly white bears on floating ice, a polar bear with a few scars comes as a surprise — but the imperfections help capture what their lives are really like, Yuyan said. “When we caricature things too much, we just completely lose the intricacies and subtleties of what it means to actually be a polar bear, the things it is that they need, and how it is that we can live alongside them.”

That’s something Iñupiaq hunters know well. The day Yuyan snapped his photograph, half a dozen polar bears were circling the hunters, hiding behind rocks, waiting for the guards to relax and the chance to grab a human for a fresh, live meal. “It’s tense, but it’s not super-duper tense, because everyone’s used to it,” Yuyan, who was named to the 2022 Grist 50 list, said. “Even though the danger is real, the number of incidents is low because the Iñupiat learned how to deal with it really well.”

Similar to how the whale hunters got used to watching out for hungry bears, people around the world are becoming accustomed to living with the simmering threat of climate change. As we’re faced with inescapable wildfire smoke and intolerable heat waves, the once attention-grabbing bear has become just one of a thousand illustrations of a world careening toward disaster: A cracked, dry riverbed. Flames engulfing a forest. Ocean waves lapping at someone’s doorstep.

Are these images becoming so common that they risk losing people’s attention, too? “You know, we’re just at the start of those sorts of things, but even I find, personally, I saturate on this,” said Andrew Derocher, a biologist at the University of Alberta in Canada. “Like, how many climate change disasters do I have to see in a given week to understand that heavy rains in Italy, or forest fires in Portugal or California or Canada, are symptoms, collectively?”

That the polar bear became the mascot of climate change at all was a bit of an accident.

“I wanted to study the natural history of polar bears. I actually never wanted to study the unnatural history of them,” said Derocher, a longtime polar bear researcher. “But I spent most of my career looking at the effects of hunting, pollution, and climate change.”

He was among the first to lay out the simple connection between polar bears and global warming: Hotter temperatures would not only melt the Arctic sea ice they live on, but also threaten their preferred prey, ringed seals. In a paper Derocher coauthored in 1993, he warned of habitat loss, lower reproduction rates, and increasing conflict with humans. But the subject didn’t really catch the media’s attention until over a decade later, in 2004, when he helped write another paper concluding that it would be “unlikely” polar bears could survive if the sea ice disappeared completely. “That one kind of went crazy,” Derocher said, spawning dozens of articles and gathering interest from conservation groups.

Derocher’s study was published just months before the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment, a blockbuster 1,800-page report that described the widespread havoc that global warming was already wreaking in the sensitive region. In the summer of 2004, in anticipation of the report’s release, a group of high-profile U.S. senators — including John McCain and Hillary Clinton — visited the Arctic island of Svalbard to see global warming’s “ground zero” firsthand.

“The term ‘Arctic’ comes from the ancient Greek word for ‘country of the Great Bear,’” McCain, a Republican from Arizona, reported back to the Senate Commerce Committee. “It has been said that we will have to rename Glacier National Park since all the glaciers are melting. Will we have to do the same for the Arctic, if the polar bear becomes extinct?” Articles began cautioning that polar bears were already shrinking and drowning.

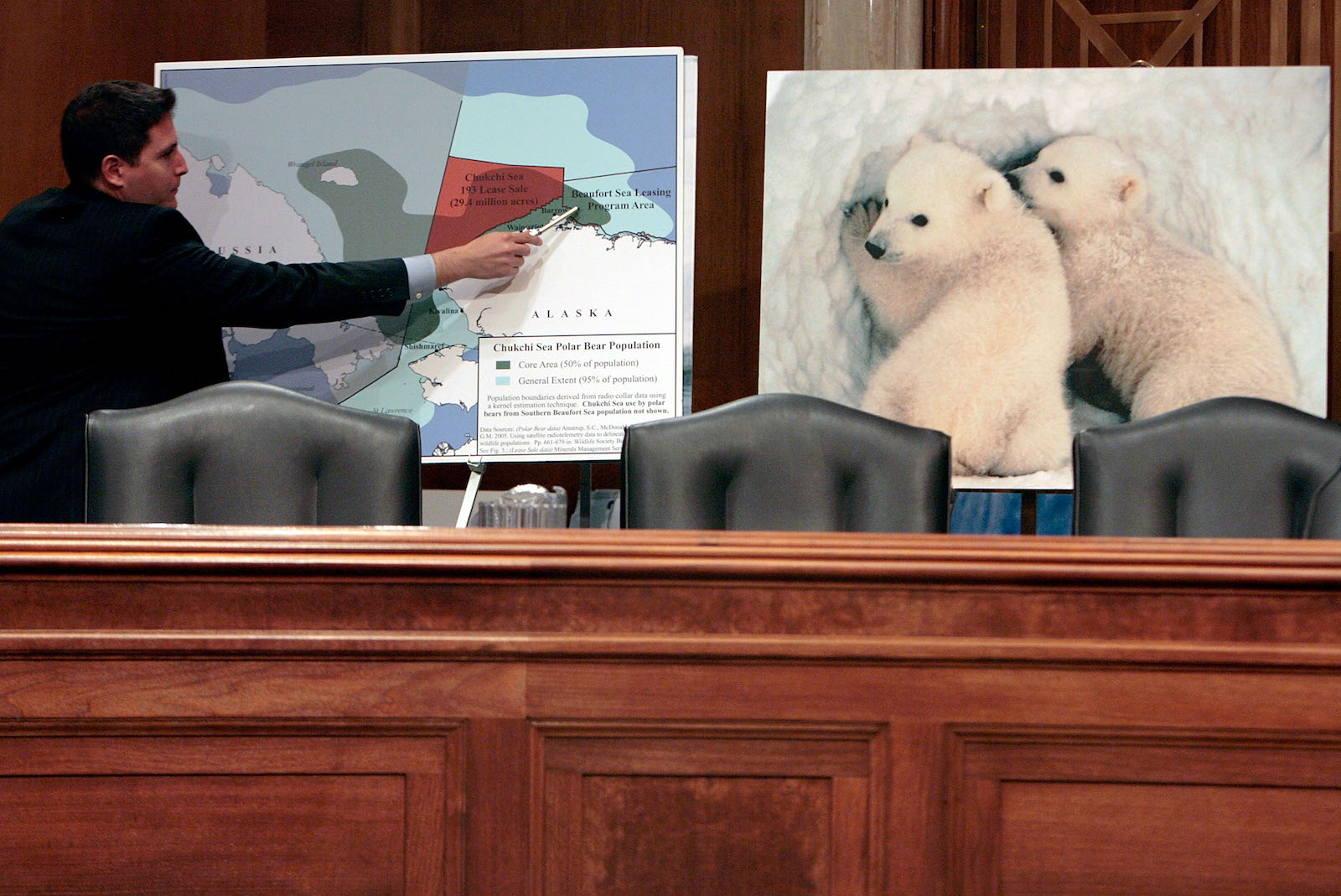

After the threat had been established, political battles kept polar bears in the headlines. The species became a flashpoint for climate deniers who cherry-picked evidence that the bears were doing just fine. In 2005, environmental groups petitioned the George W. Bush administration to get Alaska’s polar bears listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. Reluctant to acknowledge the threat of climate change, the Bush administration faced a host of lawsuits.

Chip Somodevilla / Getty Images

“Every time they missed a deadline, we brought a suit, we won a suit — it sort of ratcheted up the pressure,” said Kassie Siegel, senior counsel for the Center for Biological Diversity. The administration finally relented and listed the species as threatened in 2008, with Interior Secretary Dirk Kempthorne’s announcement accompanied by videos of happy, healthy bears.

“Trying to make polar bears the symbol of climate change, or the only symbol of climate change — I mean, that was the furthest thing from our minds,” Siegel said.

But the link between polar bears and climate change was becoming more and more ingrained.

In 2006, former Vice President Al Gore’s slideshow-turned-blockbuster hit An Inconvenient Truth featured a cheesy 3D animation of a polar bear swimming through the open ocean, trying to clamber onto a floating patch of ice only for it to crack apart upon contact. A stranded polar bear was featured on the cover of Time magazine’s global warming issue that same year with the subtitle, “Be worried. Be very worried.” In a study of the portrayal of polar bears in National Geographic magazine, Dorothea Born, a communication researcher, wrote, “No other animal has been so continuously and recurringly associated with climate change.”

It was not surprising that an animal in the Arctic was the first to draw attention as the victim of climate change, simply because the polar region has been warming four times faster than the rest of the globe. The sea ice that normally reflects most sunlight back into space has been replaced by dark blue ocean waters that absorb heat, a feedback loop that propels more warming and more ice melt.

Polar bears are considered “charismatic megafauna,” the class of large animals that tend to attract the most empathy and interest, which also includes elephants, orangutans, and pandas. Of course, sometimes the most important species in an ecosystem isn’t charismatic at all. Consider the polar cod, the Arctic’s most abundant fish, bug-eyed but otherwise unremarkable-looking. “Nobody wants to snuggle up to a little fluffy polar cod doll,” Derocher said.

But warming waters threaten the polar cod, the key link between the Arctic’s lower and upper food webs. “All the birds, all the seals, the whales all rely on this ugly little fish,” he said. Derocher sees people’s fascination with the polar bear as inherent to human nature, and noted that it’s not just environmental groups that have tapped into that interest — take Coca-Cola’s long-running marketing campaign.

The link between polar bears and climate change became so strong that context often got lost in favor of the predominant narrative. When the filmmakers and wildlife photographers Paul Nicklen and Cristina Mittermeier came across a starving polar bear in Manitoba, Canada, in 2017, the resulting footage went viral, reaching an estimated 2.5 billion people. “This is what climate change looks like,” read the text on National Geographic’s video of the emaciated polar bear. There was one problem: There was no evidence the bear was starving because of climate change specifically. All polar bears eventually die, and factors like old age, sickness, or injury can lead to starvation. The magazine editors later admitted they had gone “too far” in drawing a definitive connection to global warming.

“We had sent a ‘gut-wrenching’ image out into the world,” Mittermeier wrote in a retrospective of what had gone wrong with the photo’s reception. “We probably shouldn’t have been surprised that people didn’t pick up on the nuances we tried to send with it.”

Courtesy of Andrew Derocher

The specificity of the polar bear’s story, when turned into something that was supposed to represent climate change broadly, became its downfall. It positioned the problem as something unfolding far away (at least to the vast majority of the population that lives outside the Arctic) and hurting animals as opposed to people. “How do you convey a global issue with a single image of a polar bear?” asked Kate Manzo, who researches international development and imagery at Newcastle University in the United Kingdom. “You can’t, right?”

In an article titled “Why we’re rethinking the images we use for our climate journalism” in 2019, Fiona Shields, photo editor for the Guardian, explained that the publication would be using fewer polar bear photos going forward. “These images tell a certain story about the climate crisis but can seem remote and abstract — a problem that is not a human one, nor one that is particularly urgent.”

ALAIN JOCARD / AFP via Getty Images

The icon caused a dilemma for conservation groups, too. “When the symbol gets bigger than the region itself and people don’t realize that the polar bear is just one piece of a whole diverse web of life in the Arctic, then it can become almost a barrier,” Leanne Clare, at the time a communication manager for the World Wildlife Fund’s Arctic Program, said in 2018. (The World Wildlife Fund declined to comment for this article on the use of polar bears to promote conservation.)

It was around that year that Derocher thinks the polar bear’s status as a climate change mascot hit a “saturation point.” “In some respects, it just was no longer news anymore,” Derocher said. “Because I think you cannot find a person who can read that hasn’t heard about polar bears and climate change. It’s just such a done deal.” In addition, journalists slowly stopped offering a platform to climate deniers, eliminating the sense of controversy that had driven earlier coverage.

As climate change began to have visible effects in richer countries, the movement to new imagery happened naturally. “It’s hitting home in a way that it didn’t before,” said Manzo, who recalled seeing photos of wildfires in Spain, flooding in the United Kingdom, and the famous image of a kangaroo surrounded by flames in Australia during the bushfires in 2019 and 2020.

“Maybe polar bears aren’t on the front page anymore because you don’t need polar bears on the front page,” said Kristin Laidre, an ecologist at the University of Washington. “You can put Manhattan under a pall of wildfire smoke, and that’s a much more powerful, potent symbol, perhaps, than a critter that lives far away that most people will never see.” Twenty years ago, however, cities weren’t regularly blanketed with apocalyptic smoke. Back then, Laidre said, the polar bear “was one of the main sources of information showing that climate change was real.”

Old news or not, the facts of the situation have remained the same — polar bears are still threatened by global warming. Over the last four decades, Arctic sea ice has declined by an average of 13 percent per decade, shrinking at a faster rate than any time in at least 1,500 years. As early as the 2030s, the Arctic’s ice may completely disappear during the month of September, when it typically reaches its lowest levels.

For the estimated 2,500 polar bears that live in Baffin Bay between Canada and Greenland, bears of every age tend to be unhealthier than they used to be. They have fewer cubs, and their movement patterns have changed as the sea ice breaks up early, Laidre said.

As bears have gotten more desperate for food, they’ve also been pushed into more contact with humans. These days, you’re more likely to hear about a polar bear attacking people or eating trash than one stranded on the sea ice. Bears end up gnawing on butchered whale carcasses instead of stalking fresh seals.

ALEXANDER GRIR / AFP via Getty Images

Climate change is by no means affecting polar bear populations uniformly, though. Alaska, for example, has two populations of polar bears. While the Chukchi Sea population between Alaska and Russia appears to be doing fine, the one in the Beaufort Sea to the north of the state is shrinking, and may have declined by as much as 50 percent since before we started seeing the effects of climate change, Derocher said.

For Yuyan, the National Geographic photographer, the polar bear’s decline doesn’t fit with the tidy narrative implied by mid-2000s media coverage. “When the sea ice vanished, we expected them to all just sort of perish of starvation. And that is happening in some places,” Yuyan said. “But we also see polar bears that have adapted and figured out how to hunt from very isolated sea ice shelves, who had the ability to hunt in open-water situations, where they previously had never been observed doing that kind of thing.” Some bears, in other words, are adapting, though climate change remains a real threat to their survival.

Yuyan thinks it’s a good thing that the world is moving on from the photographs of the sad polar bear stranded on the ice. It gives the impression that the Arctic is “either frozen, or it’s all doomed. And it sends the message that polar bears are helpless victims,” he said. “You’re basically just ironing in cultural biases. And that’s not really our job. Our job isn’t to tell people what they already know. They already know it. Our job is to tell them what they don’t know, to surprise people, and to help them understand that the world is more complicated and more beautiful than we will ever know.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Why the climate movement doesn’t talk about polar bears anymore on Aug 2, 2023.