On a warm spring day in Chiang Mai, Thailand, a thick blanket of gray smog covers the city. The surrounding Khun Tan mountains are obscured by a dense haze, and residents are urged to stay indoors. Outside of an unassuming government building on the outskirts of the city, dozens line up for N-95 masks being handed out by civil servants. The air hangs heavy in their lungs and stings their eyes. For those who must venture outdoors, the masks provide a layer of protection.

Inside the building, local officials are strategizing about more holistic ways to address the air pollution crisis. Once a week, a group of 15 to 20 gathers in a large conference room, joined by another 80 or so online, to mount their campaign against the fires that engulf the region every year. They’ve dubbed it the “War Room.”

It’s the headquarters of a provincial effort to combat the pollution crisis using technology, rooted in a novel system of fire management: a mobile application called FireD.

Carmela Guaglianone

Chiang Mai — Thailand’s second largest city and a tourism hotspot — frequently tops charts as the world’s most polluted city during the first few months of the year. Significant industrial and car pollution contribute to an already dirty baseline, but widespread agricultural burning is considered the primary culprit. The annual “burning season” runs from January to April, when farmers traditionally have set fires on their land to dispose of waste or clear weeds from their field ahead of the planting season. Unique weather conditions in northern Thailand combine with the region’s mountainous geography to stagnate the air and trap the smoke. One of the byproducts of the burning is PM2.5, a fine particulate matter associated with a number of detrimental health effects. Breathing it in at levels common in Chiang Mai is comparable to picking up a smoking habit.

A working group in the Thai Parliament is in the process of drafting a Clean Air Act to address pollution across the country, but several years are expected to pass before an official law is put forth. In the meantime, demonstrable success of the FireD system could be a breath of fresh air — and a scalable solution for northern Thailand and surrounding countries, like Laos and Myanmar.

The problem also extends far beyond this region, affecting communities across Asia, Africa, and North America — even the United States. Smoke from local blazes can cover huge distances, contributing to poor health outcomes in some of the world’s most populous cities. A study in Nature Communications found that pollution from burning crop residue in India caused between 44,000 and 98,000 premature deaths there each year from 2003 to 2019. The release of smoke and particulate matter into the atmosphere also comes with consequences for ecosystems, waterways, and the climate.

Guillaume Payen / Anadolu via Getty Images

In a country where agriculture employs one-third of the total labor force, burning has long been a natural part of the yearly crop cycle. In Thailand’s north, 33 percent of farmland is used to grow corn, with some 80 percent of that going to animal feed. Much of the agricultural burning in the region can be traced back to farms growing feed for livestock, like corn or rice.

In the north, the steep mountain terrain makes it difficult for tractors and combine harvesters to cross fields to integrate waste from the last harvest into the soil, or for trucks to reach the fields to haul the waste away. And this machinery is expensive, often too costly for smallholder farmers, who make up the majority of farmland stewards in the region. Instead, farmers resort to burning to clear weeds, expand their planting area, and dispose of agricultural waste from the previous season ahead of planting — commonly referred to as slash-and-burn practices.

The Thai government enforces a no-burn policy from January through April, but the restrictions have had a limited impact. Enforcement is inconsistent, and farmers are often scapegoated for the pollution problem despite having few alternatives to burning.

Chiang Mai is now trying a more targeted approach to tackle its annual smog problem. While farmers can still face penalties for setting fires that get out of hand, leaders in Chiang Mai are hopeful that a more compassionate system can be introduced that balances farmers’ needs with the need to control air pollution.

In 2019, a team of professors at Chiang Mai University, or CMU, had an idea. Using imagery and data from NASA satellites and thermal drones, they could get a real-time overview of the region’s pollution levels. This data could then be used to determine when and where farmers should be allowed to do controlled burns across northern Thailand. The idea turned into a research paper, which turned into FireD, a quasi-translation of fị thī̀ dī, meaning “good fire.” Instead of burning indiscriminately, farmers can submit requests to burn through the app. Using the data accumulated through FireD, local officials can then approve or reject requests depending on the existing atmospheric conditions.

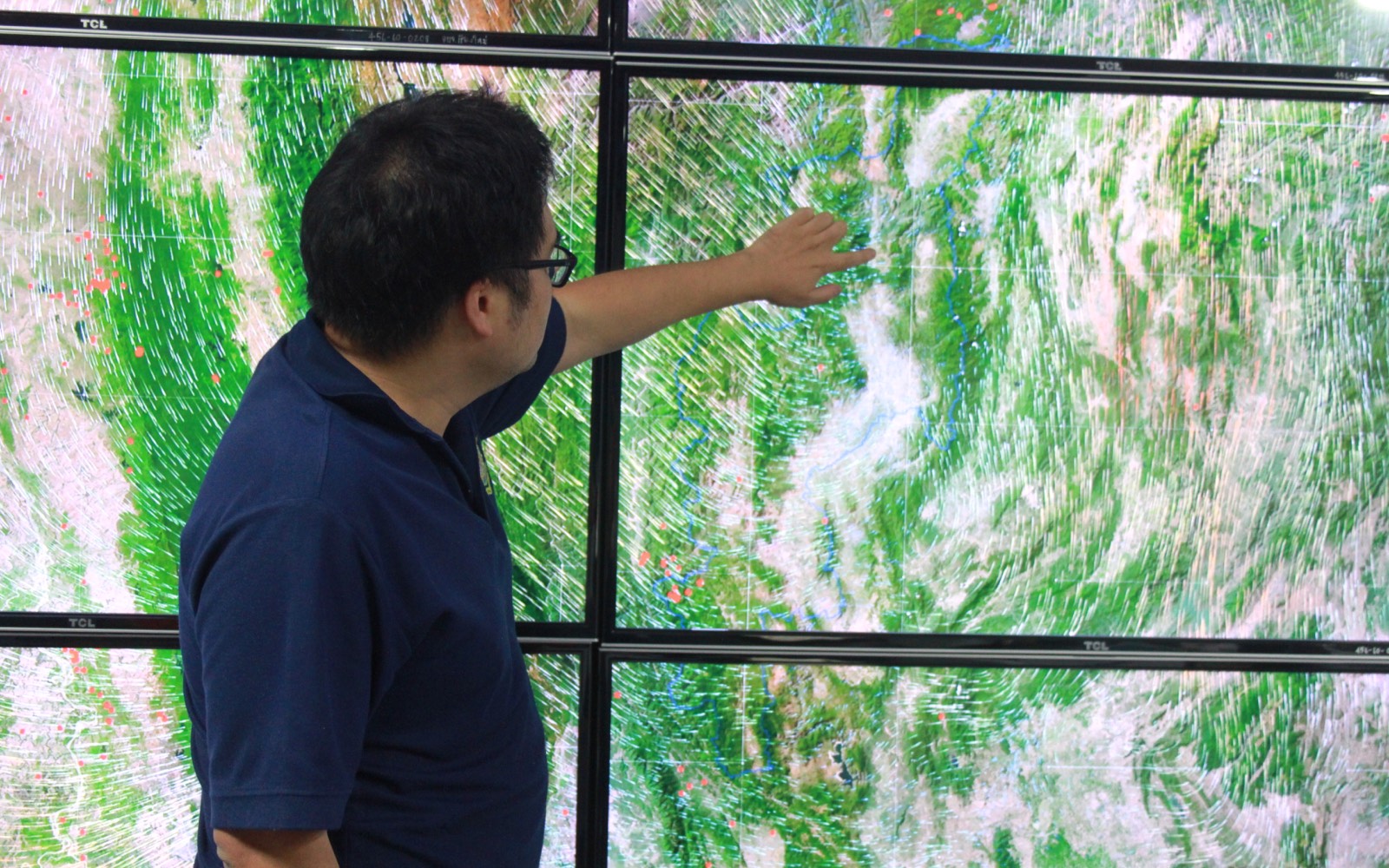

Inside the War Room, an entire wall is filled from floor to ceiling with TV monitors displaying data pulled from FireD. The screens provide a real-time glimpse of the severity of the burning and smog levels at any given time. Arrows on topographical maps follow the movement of smog across northern Thailand; video feeds show a 24-hour time lapse of haze accumulating over Chiang Mai; and data tables categorize the burn sites based on size, location, and duration of burning.

Carmela Guaglianone

These screens are manned by Somkid Panyadee, the director of Chiang Mai’s Office of Natural Resources and Environment and the de facto War Room general. He leads local officials through the process of accepting or rejecting burn requests. If conditions are bad enough, War Room officials can also use FireD data to help determine whether emergency fire fighting services need to be deployed across the region.

Panyadee sees this newer — though still imperfect — system as a step in the right direction, and a more realistic approach than a blanket no-burn policy. “At present this is the best hope,” he said.

Chaya Vaddhanphuti, a lecturer at CMU’s Department of Geography, is an independent researcher working with the developers of FireD to study the app’s rollout across Chiang Mai province. He sees FireD not only as a way to control fires, but to reframe the conversation around those who burn. “The app was called FireD, or ‘good fire’, as a way to recover the reputation of people who need to light these fires for their own well-being,” he said.

In 2024, FireD fielded more than 14,000 burn requests, covering nearly 155,000 acres. But while researchers are optimistic the system could shift the way agricultural burning is approached in the country, there are obstacles to broad implementation.

“We have a lack of consistent understanding of the use of FireD. I think this is quite clear,” said Vaddhanphuti.

Due to lack of access to technology and internet service, farmers are typically expected to complete a written form that mirrors the app’s interface and submit it to their local village chief. The chiefs then submit these forms to program representatives for their districts or subdistricts, of which there are 204 in Chiang Mai. This data is fed into the FireD system. Officials contact the farmer directly three days ahead of their burn to let them know if their request is approved or delayed, and to discuss the wildfire mitigation techniques they plan to use.

Carmela Guaglianone

Instead of undergoing the request process, farmers often just wait until May to burn so they can skirt around the no-burn policy, said Chief Pipat Tanarawithaya, a village leader in the province. Not a single farmer in his jurisdiction filled out paperwork for this burn cycle, he said.

Farmers in the rural regions of northern Thailand must weigh the need to support themselves and their families against burning’s environmental and health effects — including for themselves.

This year, forest cover in Mae Chaem, an agriculturally rich district about 75 miles southwest of Chiang Mai, is visibly parched. Thipawan, a farmer from a village in the district, has been growing on this land for nearly all of her 54 years, and nearly all of her land is dedicated to corn. Her parents grew here before her. Smoke pollutes her youngest memories.

When Thipawan decides to burn, she chooses the day strategically. She considers the weather, but first and foremost she considers the needs of her land. If she burns too early, weeds will grow back on the field and make it difficult to plant — she’d need to burn a second time. Thipawan opts to burn in May and has not yet used FireD.

Carmela Guaglianone

Like many of her neighbors, Thipawan has attempted to replace some corn plots with crops that don’t require burning — like mango, bamboo, or teak trees. The transition has yet to pay off; the markets for those products are less sure, and it takes time to build up the inventory.

She has also considered switching to more lucrative crops, like vegetables. With more funds, it could be easier to invest in alternative means to get rid of agricultural waste. But those crops are water intensive, and this soil is thirsty for much of the year. Corn relies only on rainwater.

If she were to use the app, she said, it would be challenging for her to postpone her planned burns for more than a week from the date she picked, even if officials told her that it was a bad time. If she doesn’t prepare for planting in time, it may affect her yield. And if she’s burning a large plot, she needs to ask people to help her oversee and monitor the blaze. For her, and many farmers like her in the region, changing her farming practices is easier said than done.

Another burning season ended in May, with some improvements in air quality evident from last year. Incidents of burning hotspots were down 3 percent from the previous year in protected forest areas, where most fires take place — and overall burn-scarred acreage was almost cut in half, according to an aggregation of FireD data. The tally of days with dangerous PM2.5 levels also decreased by 24 percent, the data showed. However, public communication, oversight, and resistance to change remain key hurdles to widespread use of FireD in the coming years.

To raise awareness of the new system, local leaders like Chief Tanarawithaya have started holding meetings with villagers in December, ahead of burn season, to inform them of the new rules and how the process works. Some forest officials are going door to door to educate villagers.

In a few areas in Thailand’s north, adoption of the system has been more widespread, due to differing levels of technological access, expertise among local officers, or specific village dynamics.

FireD is seen by provincial officials and local researchers alike as a promising tool for fire management, originating from the country’s worst affected region. The apparatus is complicated — merging modern technology with traditional practices requires a unique type of innovation, and a high level of cooperation between the parties involved. But what it represents is a compromise. With FireD, officials are testing a data-driven approach to addressing air pollution that also takes into account the needs and realities of Thai farmers.

“Indigenous groups in rural areas have always been targeted and blamed for the pollution problem,” said Vaddhanphuti, the app researcher. “We don’t want FireD to become a tool for reinforcing these blames. Instead, we want it to be an agent of change, so these farmers can continue their rotational farming practices in a less harmful way.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline When is it safe to burn fields? In Thailand, farmers can turn to a new app to check. on Jul 12, 2024.