This story is co-published with The Assembly and Spotlight on Poverty and Opportunity. This reporting project was supported by The Uproot Project Environmental Justice Fellowship and produced through the Environmental Justice Oral History Project.

Paul Fisher first heard about the Sampson County landfill on a radio talk show in the early 1990s. Folks were adamantly discussing plans to transform Sampson’s municipal solid waste facility in Roseboro, which had officially been in operation since 1974, into a massive regional dump site that would regularly draw from 44 counties.

Fisher, who lives less than a mile away in the Roseboro neighborhood of Snow Hill, and other residents quickly organized against it, frustrated that the county hadn’t done more to engage them in the process. But officials largely ignored their protests, and the expanded site that opened in 1992 has since grown from an approximate 350 acres into over 1,300 acres — the largest landfill in North Carolina.

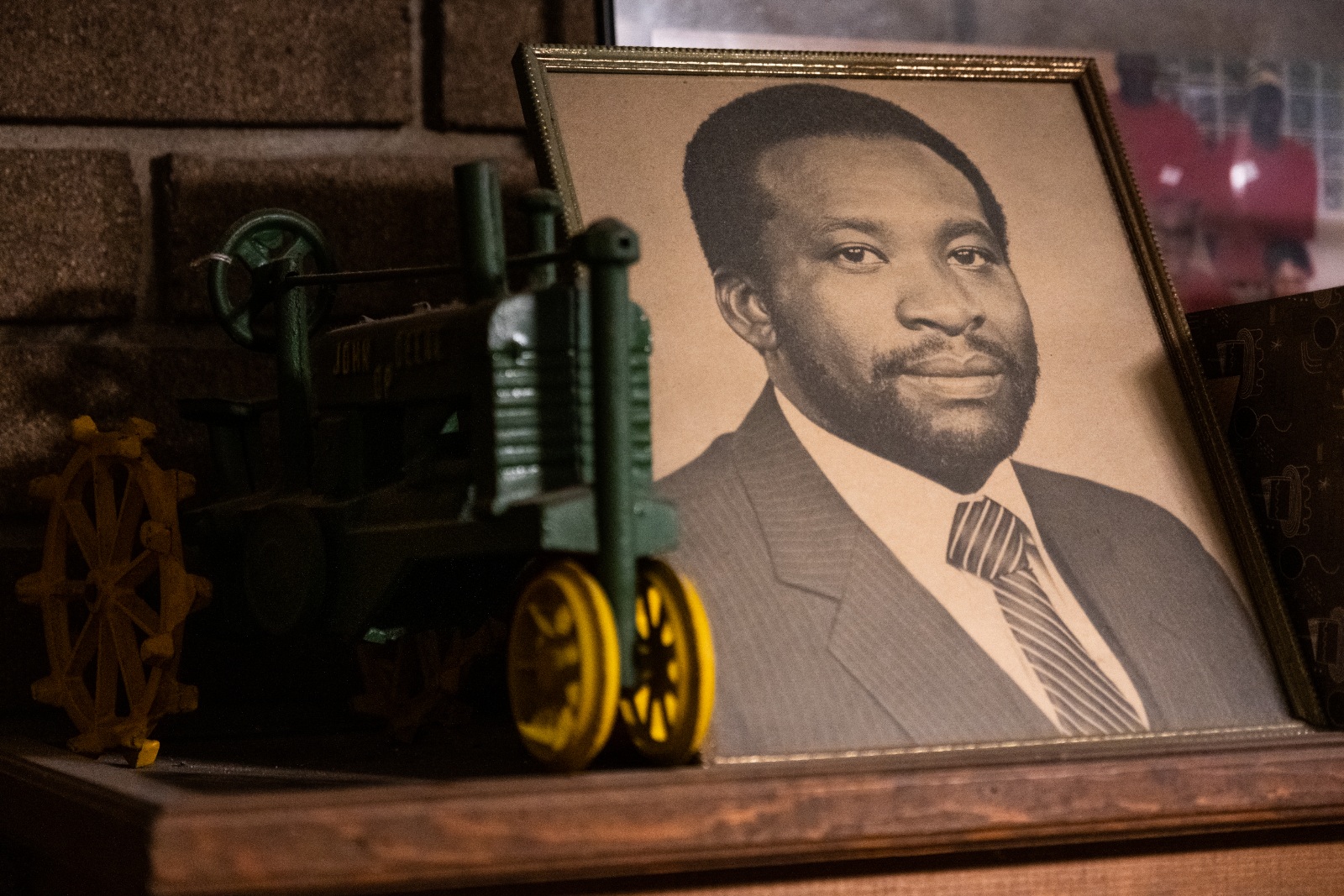

Like many residents of Snow Hill, Fisher traces his roots here to the early 1830s, when his great-great-great grandfather was enslaved about eight miles away. His ancestors eventually purchased land just a few miles from where they once labored. Fisher, 75, has spent his whole life here, save nine years in the military. He returned in 1975 to give his two daughters the same rich childhood he had.

But his children have moved away. They didn’t want to live with the smell and pollution of a dump next door. Now 30 years since the site was regionalized, Fisher is still speaking out.

“It takes three generations to accumulate generational wealth: One to start it, one to build it, and one to enjoy it,” he said. But for his family, the dump has made passing on wealth difficult.

Snow Hill was once a centerpiece of Black excellence in Sampson County: a multi-generational community that had its own barber shop, Boy Scout troop, and community center. Many teachers, lawyers, and doctors lived there; most people were college-educated, or ensured their children would be. Farmers and backyard gardeners drew water from their own wells, grew almost all of their food, and hunted game.

The community is still heavily agrarian, but much of the natural beauty is gone—and so is the prosperity.

Cornell Watson for The Assembly

You notice the smell first, a pungent odor detectable from about 2 miles away; residents say it’s constant and debilitating. Within a few minutes outside, the odor settles into clothing. Homeowners close their vents just to get a good night’s rest, but describe waking up with sinus headaches or shortness of breath. It leaves folks coughing, wheezing, and riddled with respiratory illnesses.

It attracts pests: buzzards, rats, and even black bears have caused property damage and car accidents. Fisher now carries a gun outside his house, as a pack of 10 to 12 wild dogs have become a constant aggressive presence. Although he’s brought this issue and his other odor, pest, and health concerns to county commissioner meetings, he’s received little response.

“As far as the landfill is concerned, you can get up and speak until you’re blue in the face, but you don’t ever get any results,” he said.

Dumped and dispersed

GFL Environmental, a Canadian solid waste company, operates Sampson’s landfill. County commissioners say items like vehicle waste, tires, appliances, untreated medical waste, and animal byproducts that have not passed state inspection are not allowed, nor is anything radioactive, volatile, explosive, toxic, or hazardous as defined by state and federal standards.

But residents say they’ve seen waste that raises concerns — in particular, a lot of dead hogs and industrial waste. According to the Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC) and local reports, asbestos, sludge containing Gen X from a Chemours wastewater facility, contaminated personal protective equipment, creosote-soaked wood, and ash from burned coal, wood, and tires have been dumped in the landfill for years. In some cases, the community was not informed about potentially harmful materials dumped in the landfill until years later.

County officials tout the landfill as an economic benefit, as it brings in about $2.3 million in host fees annually — income that’s gone toward essential services like ambulances, offset recycling site costs, and helped keep taxes low.

Sampson County Board of Commissioners Chair Jerol Kivett said in an email that while the funds are important, “they do not, however, negate our responsibilities for environmental stewardship.” But the county has ignored the health concerns the landfill creates, said Maia Hutt, a staff attorney for SELC who is working with the local Environmental Justice Community Action Network on the landfill.

Cornell Watson for The Assembly

A 2021 N.C. Division of Air Quality permit application review showed it was emitting about 32 tons of hazardous air pollutants per year as of 2019 — almost twice as much as it did in the previous four years. Per the permit application, EPA considers the landfill “a major source” of hazardous emissions, including the liver- and kidney-damaging chemical toluene and carcinogens benzene and ethylene dichloride. In 2020, the landfill ranked first in the state for vinyl chloride emissions, which have been linked to rare forms of liver cancer.

Methane emissions are also a growing concern, said Hutt, and the landfill is considered one of the biggest emitting landfills in the country at nearly 33,000 tons in 2021. Sampson County ranked second in the country for methane emissions from municipal solid waste landfills that year.

Groundwater contamination is also a concern, though many Snow Hill residents were moved off well water and onto county water soon after the landfill was regionalized. The county gets its water from groundwater stores in the nearby cities of Clinton, Garland, Roseboro, and Turkey, and many residents still don’t trust what comes from their taps.

Researchers at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill released a report on water tests in August 2023 that found nearby waterways had about 10 to 20 times more PFAS — a group of forever chemicals that has been linked to liver disease, kidney disease, developmental and immune system impairments, and cancer — than sites upstream.

Whitney Parker, a fourth-generation Snow Hill resident and community activist, discovered as a part of this study that the stream running behind his grandmother’s property was contaminated with PFAS. “And if you have land you want to try to rent out for people to use, it won’t pass the soil test. We’ve lost a lot of income because of that toxic place,” he said.

A detailed EPA facility report lists no violations of the Clean Air Act or Clean Water Act at the landfill over the last five years. But Hutt stressed that complying with policy doesn’t mean there’s no harm. “The question is, can you be in compliance with your permit and still be hurting people? The answer is yes,” she said. “And I think that’s where we see this legacy of weak permitting in communities of color.”

Cornell Watson for The Assembly

While the landfill’s permits limit pollutants like benzene and vinyl chloride, a chemical known as 1,4-dioxane that is thought to cause liver cancer is not limited. There is no federal standard for emerging contaminants like this, and although the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality has adopted a groundwater standard for 1,4-dioxane and regulates its release, GFL claimed in its July 2022 water quality report that it is not required to control its release. The report noted that the substance was “detected at quantifiable concentrations” greater than state groundwater standards at landfill monitoring locations.

DEQ said tests for 1,4-dioxane have shown decreasing levels at the locations it monitored, and at concentrations that are not expected to travel beyond the allowable 300 foot compliance boundary. “The state and the facility continue to monitor the situation and actions will be taken if required by monitoring results,” wrote Melody Foote, a DEQ public information officer.

Advocates say permitting also does not take the cumulative impacts of multiple waste streams into account. “There is not a house in this community that has not had a person who has suffered from some type of cancer or kidney failure,” said Parker. In addition to the landfill, Sampson is the second-largest hog-producing county in the country, a growing poultry producer, and home to an Enviva wood pellet plant.

A community left in the dark

County commissioner briefings dating back to the early 1970s seem to indicate that the decision to place the landfill in Snow Hill was rushed.

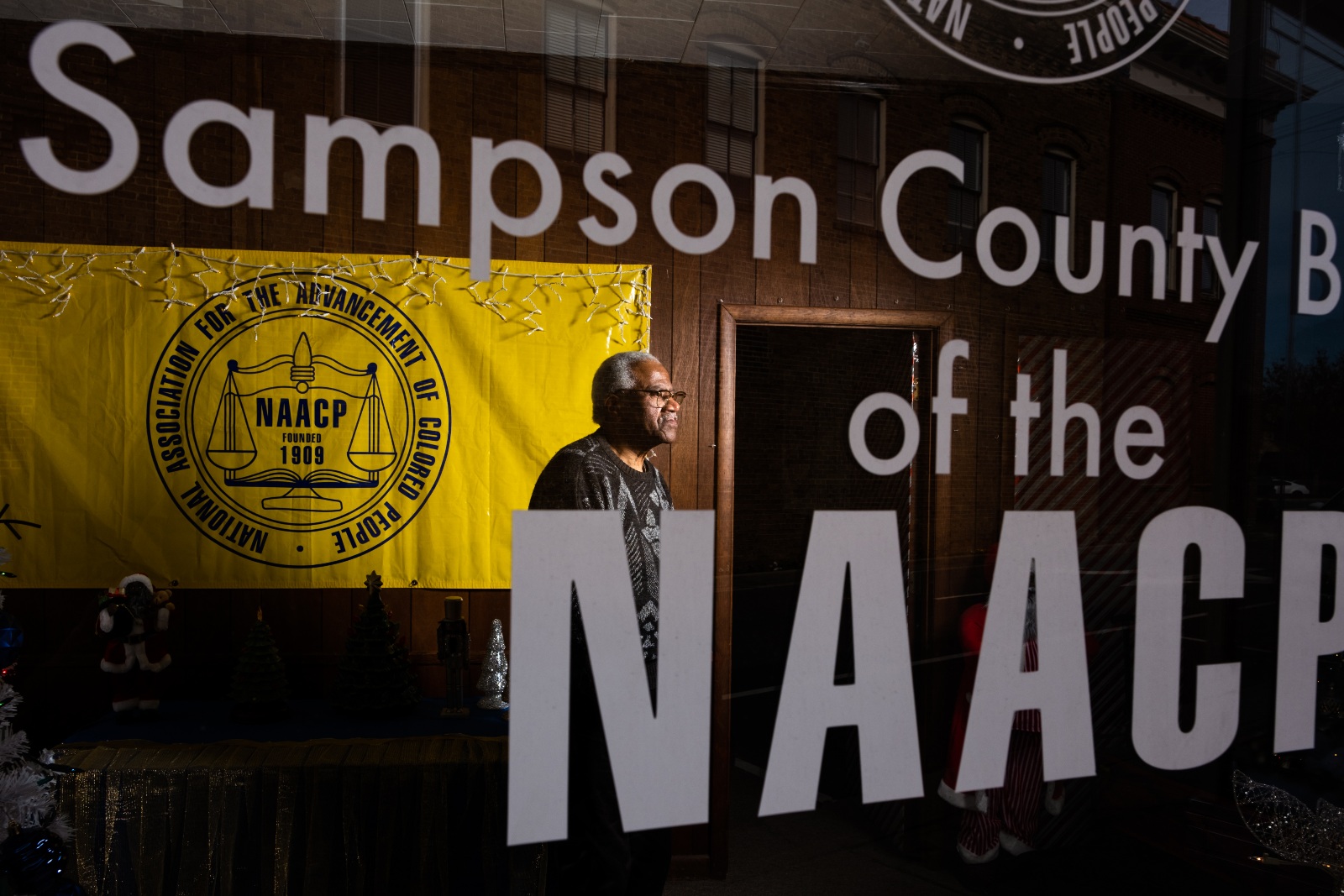

Sampson County NAACP President Larry Sutton believes it was also racially motivated, based on his research into records at the county clerk’s office. Sutton, 73, was born on his family’s land in Clinton about eight miles down the road from Snow Hill. But he spent a lot of time as a child riding up and down the old two-lane Highway 24 that bisected the community. In June 1970, the Sampson County Commissioners set aside funding to establish a solid waste disposal program that consisted of several smaller, easy-access municipal landfills across the county. But the plan received a number of complaints from residents about odor, and air, water, and soil contamination.

The county decided to consolidate its waste system into a single centralized landfill site in Snow Hill in March 1973. Environmental surveys determined that only about 30 percent of the Snow Hill site was suitable for a central landfill due to a high water table, but the county still approved construction, claiming they could fill the unsuitable land with tires and other solid materials.

Cornell Watson for The Assembly

Many community elders don’t recall learning about the landfill until after it was already built. According to Kivett, the original landfill, though small, was not lined and would not have met modern environmental standards now set by the EPA. It was prone to massive fires caused by unchecked methane emissions — at least twice a month according to Parker, a child at the time — that would burn for days.

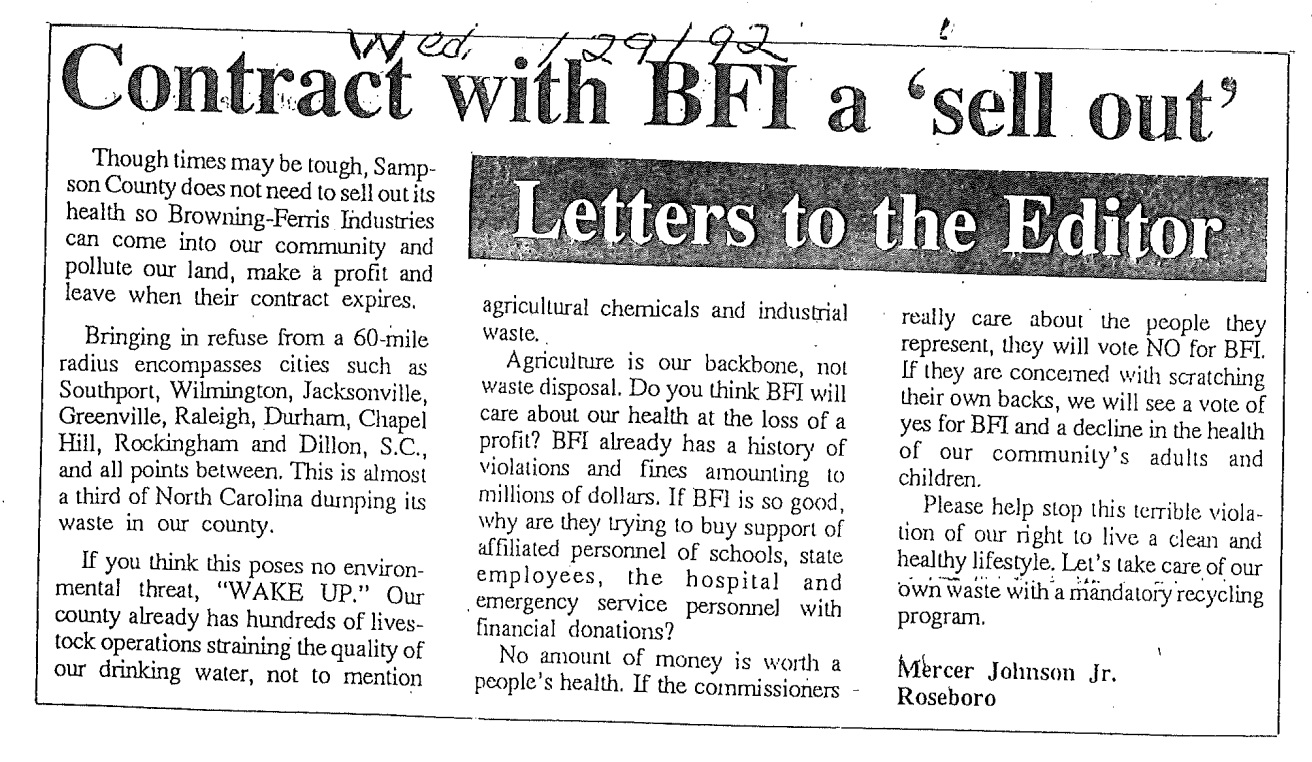

“There is plenty of land in our county where no one lives,” said Shelda Parker, 76, one of the 1992 protesters. “They could have put that landfill anywhere, but they chose to put it in the middle of our community.” In February 1992, the county entered a contract with Browning-Ferris Industries (BFI) to privatize operations at the landfill and transform it into a regional site. Snow Hill residents publicly pushed back against the expansion. Despite assurances that the facility would not expand beyond about 525 acres, some feared that BFI would turn their community into a mega-landfill site. For many others, the concern was not about meeting federal regulations, but about whether Snow Hill should have to receive waste from “almost a third of North Carolina.”

“They fought tooth and nail,” said Whitney Parker, whose older cousin Ed Parker was a founder of Concerned Citizens for Sampson County, which spearheaded the protests in the ‘90s. The group wrote op-eds, held community education sessions, canvassed, and spoke out at commissioner meetings leading up to the vote.

The board of commissioners was majority white at the time, and when it came time to vote, all of them approved. “It was unanimous — no consideration for the protests or for anyone’s health, clean air, soil, or property values,” Parker said. Even the commissioner for District 4, who lived in Roseboro, voted in favor.

Looking to the future

Whitney Parker grew up in Snow Hill on land that his parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents cultivated before him. He was born four years after the original municipal landfill was built and describes his childhood as a “paradise.”

He went to college in Greensboro and returned home in 2003 to take care of his parents. Their downturn was swift and unexpected — an independent duo who suddenly found themselves in and out of the hospital. His mother was diagnosed with kidney disease followed by cancer. Both passed within six months of each other in 2021.

“Almost everyone in the community is going through what I’ve gone through,” he said. He stayed in Snow Hill and has since dedicated his time to fighting for the closure of the landfill.

Cornell Watson for The Assembly

Cornell Watson for The Assembly

“As a fourth-generation heir, I can’t enjoy the fruits of all my grandparents’ labor. We’re the last gatekeepers for preserving what we saw our grandparents work on,” said Parker.

Parker is among the residents who have renewed the push to hold the county and landfill accountable, connecting with other North Carolina organizations involved with Justice40: A Time for Righteous Investment, a southern-based climate justice group.

“The biggest motivation for me is paying homage to the people who fought before me,” Parker said.

Among their concerns is another company, Sapphire RNG, which has approached the county and DEQ to collect methane from the landfill via a digester.

It’s been touted as a solution to the methane problem: If the landfill won’t close, at least they can reduce the emissions and use what’s collected to produce energy. Commissioner Kivett pointed to it as evidence that GFL is putting “an emphasis on expanding technologies to manage potential environmental hazards.”

But community members say it’s another way for a private business to profit while they still experience harm.

The facility is also projected to bring more traffic. About 250 trucks haul waste to the site daily, which is expected to increase as the landfill begins capturing and transporting renewable natural gas offsite. The current trucks are prone to spillage on their way to the facility, leaving waste, sludge, and sometimes dead animals on the road that get swept into people’s yards or left for young people to stand in as they wait for the bus. Despite requests for truck figures from DEQ and SELC as a part of permit review, Sapphire RNG did not share traffic estimates.

On October 4, 2023, DEQ approved Sapphire RNG’s air permit request, after SELC and community groups requested additional information about potential impacts. While Hutt, the SELC staff attorney, noted that some updates were made to the permit, such as including a PFAS-monitoring provision, this “must be the beginning, not the end, of the state’s efforts to protect the people of Snow Hill.”

In a move that surprised the community, the DEQ announced in early October that it would invest more than $4 million to improve water infrastructure in Sampson County. The state has also begun conducting PFAS water testing in the Snow Hill community, and on November 16 held a meeting to update those residents still using well water on the status of private wells. Thirty-one wells had been tested, and six households are now receiving bottled water from the state due to high PFAS concentrations.

But DEQ has not officially connected the PFAS contamination to the landfill. And some community members are skeptical of the new interest in Snow Hill’s well-being. “This is an attempt to cover up and counter future litigation,” Parker wrote in an email to The Assembly. His organization hopes to conduct water testing in 2024 to ensure the state data is accurate.

In September 2023, Snow Hill community members filed a formal complaint against the landfill to the Sampson County chapter of the NAACP in the hope that the organization can advocate on their behalf. “Residents of the Snow Hill community need to be part of the conversations, in the room, with a seat at the decision-making table,” said Sutton in a written statement. “What is more basic to healthy living than ensuring clean water and air?”

Taryn Ratley, a fourth-generation Snow Hill resident and Parker’s cousin, says the county needs a more comprehensive health assessment. “We’re going in debt buying air purifiers, water purifiers, candles, fly spray, fly traps,” she said. “The buzzards are picking the shingles off our roofs and the insurance won’t pay for it. It’s almost like a prison in our own houses.”

Cornell Watson for The Assembly

Cornell Watson for The Assembly

A comprehensive study would include interviews with residents, reviews of health records, and evaluating whether there is a causal relationship between the landfill and poor health outcomes in the community. In October 2023, the Environmental Justice Community Action Network in partnership with researchers from Grambling State University in Louisiana and Georgia State University announced they would perform a health assessment of Snow Hill residents like what Ratley suggested. Other opportunities for formal community engagement are fast approaching. The landfill’s current air permit expires in June, and it will need to submit a new permit application to DEQ. The process gives the community another chance to plead their case about the landfill’s harms.

The smell is another issue. State law requires landfills to have odor “management practices” or install “control equipment.” But Hutt noted that the Sampson County landfill does not, while one located in a predominantly white community in Apex does.

“Both the company itself and our state seem to think it’s okay to do the bare minimum because they’re in Sampson County,” Hutt said.

DEQ spokesman Shawn Taylor said the Sampson County landfill has not met the requirements necessary for an odor management plan, which include “existence of objectionable odors” as determined by DEQ, but the agency is “currently investigating odor complaints.”

Landfills in the U.S. have an average lifespan of 50 years, and according to DEQ, the Sampson County landfill is not expected to close until 2042 — which will put the community at about 70 years of waste collection. Fisher fears that even then, the county could just build a new one nearby.

“There’s no county, I don’t think, in North Carolina that would accept a regional landfill. Not nowadays,” he said. “And the only way this gets shut down is if it goes somewhere else.”

Fisher is just hoping to curb the impacts enough to keep his family’s land in the family. “They don’t make any more land,” he said. “If my father or grandfather accumulated some land, then there’s no use in me giving it away and not taking care of it.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline A decades-long battle against North Carolina’s largest landfill is ramping up on Jan 19, 2024.