Earth Hour 2024, the “Biggest Hour for Earth” of the year, takes place on March…

The post Earth911 Podcast: EPAM Continuum On Amplifying The Impact Of Earth Hour appeared first on Earth911.

Earth Hour 2024, the “Biggest Hour for Earth” of the year, takes place on March…

The post Earth911 Podcast: EPAM Continuum On Amplifying The Impact Of Earth Hour appeared first on Earth911.

Earth911 spoke with gardening expert Melinda Myers to find out how to cut fresh, long-lasting flowers from your garden without harming your plants. Read on for her top tips.

The post Tips for Snipping Spring Flowers Without Harming Your Plants appeared first on Earth911.

It’s almost that magical time of year that the Humane Society of America likens to a “natural disaster.” Kitten season.

“The level of emotions for months on end is so draining,” said Ann Dunn, director of Oakland Animal Services, a city-run shelter in the San Francisco Bay Area. “And every year we just know it’s going to get harder.”

Across the United States, summer is the height of “kitten season,” typically defined as the warm-weather months between spring and fall during which a cat becomes most fertile. For over a decade, animal shelters across the country have noted kitten season starting earlier and lasting longer. Some experts say the effects of climate change, such as milder winters and an earlier start to spring, may be to blame for the uptick in feline birth rates.

This past February, Dunn’s shelter held a clinic for spaying and neutering outdoor cats. Although kitten season in Northern California doesn’t typically kick off until May, organizers found that over half of the female cats were already pregnant. “It’s terrifying,” Dunn said. “It just keeps getting earlier and going later.”

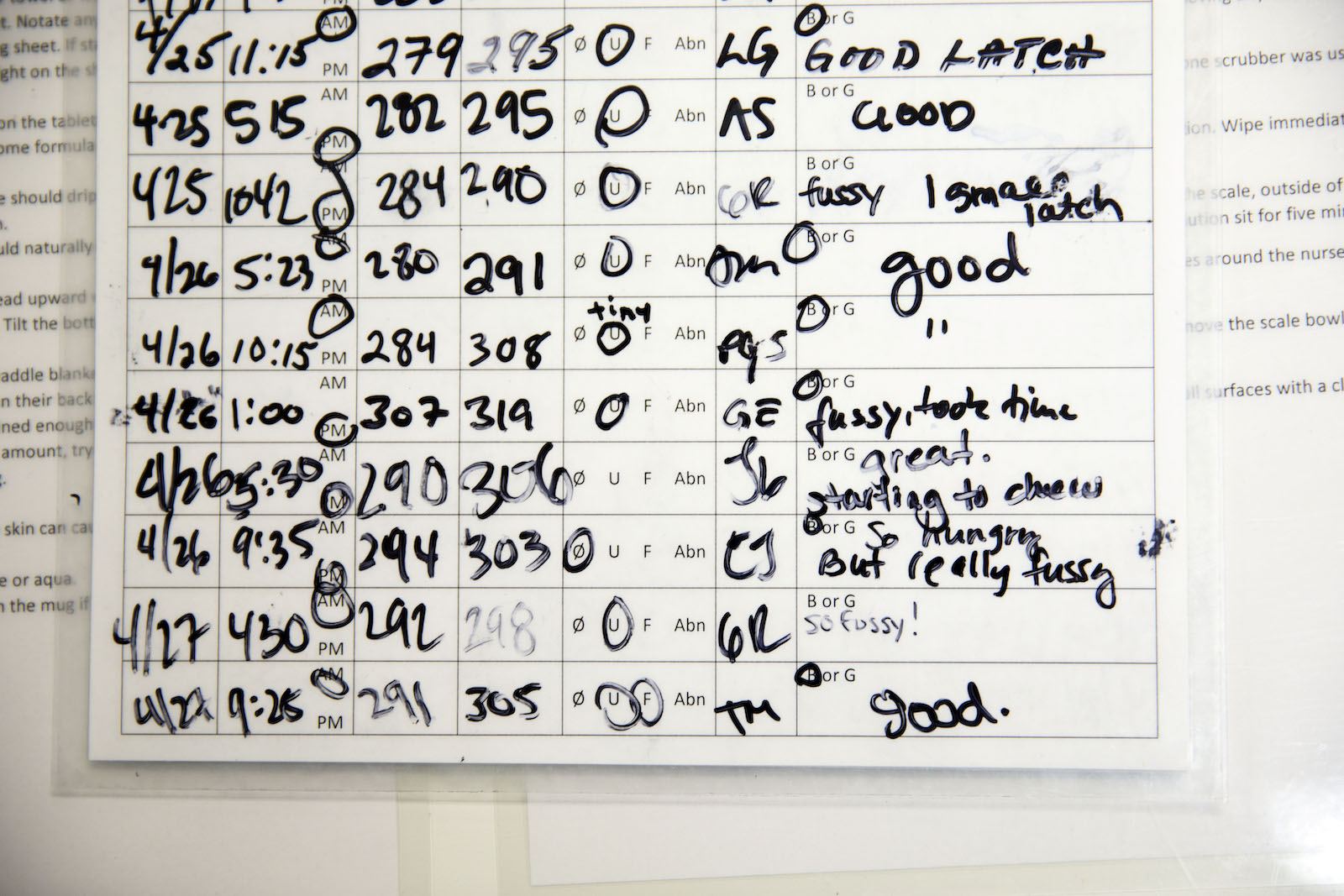

Unweaned kittens rest inside terrariums at the Best Friends Animal Society shelter in April 2017 in Mission Hills, California. A chart helps workers keep track of their behavior, weight, and care schedule. Patrick T. Fallon / The Washington Post via Getty Images

Cats reproduce when females begin estrus, more commonly known as “going into heat,” during which hormones and behavior changes signal she’s ready to mate. Cats can go into heat several times a year, with each cycle lasting up to two weeks. But births typically go up between the months of April and October. While it’s well established that lengthening daylight triggers a cat’s estrus, the effect of rising temperatures on kitten season isn’t yet understood.

One theory is that milder winters may mean cats have the resources to begin mating sooner. “No animal is going to breed unless they can survive,” said Christopher Lepczyk, an ecologist at Auburn University and prominent researcher of free-ranging cats. Outdoor cats’ food supply may also be increasing, as some prey, such as small rodents, may have population booms in warmer weather themselves. Kittens may also be more likely to survive as winters become less harsh. “I would argue that temperature really matters,” he said.

Others, like Peter J. Wolf, a senior strategist at the Best Friends Animal Society, think the increase comes down to visibility rather than anything biological. As the weather warms, Wolf said people may be getting out more and noticing kittens earlier in the year than before. Then they bring them into shelters, resulting in rescue groups feeling like kitten season is starting earlier.

Regardless of the exact mechanism, having a large number of feral cats around means trouble for more than just animal shelters. Cats are apex predators that can wreak havoc on local biodiversity. Research shows that outdoor cats on islands have already caused or contributed to the extinction of an estimated 33 species. Wild cats pose an outsized threat to birds, which make up half their diet. On Hawaiʻi, known as a bird extinction capital of the world, cats are the most devastating predators of wildlife. “We know that cats are an invasive, environmental threat,” said Lepczyk, who has published papers proposing management policies for outdoor cats.

Scientists, conservationists, and cat advocates all agree unchecked outdoor cat populations are a problem, but they remain deeply divided on solutions. While some conservationists propose the targeted killing of cats, known as culling, cat populations have been observed to bounce back quickly, and a single female cat and her offspring can produce at least 100 descendants, if not thousands, in just seven years.

Although sterilization protocols such as “trap, neuter, and release” are favored by many cat rescue organizations, Lepczyk said it’s almost impossible to do it effectively, in part because of how freely the animals roam and how quickly they procreate. Without homes or sanctuaries after sterilization, returning cats outside means they may have a low quality of life, spread disease, and continue to harm wildlife. “No matter what technique you use, if you don’t stop the flow of new cats into the landscape, it’s not gonna matter,” said Lepczyk.

Rescue shelters, already under strain from resource and veterinary shortages, are scrambling to confront their new reality. While some release materials to help the community identify when outdoor kittens need intervention, others focus on recruiting for foster volunteer programs, which become essential caring for kittens who need around-the-clock-care.

“As the population continues to explode, how do we address all these little lives that need our help?” Dunn said. “We’re giving this everything we have.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Kitten season is out of control. Are warmer winters to blame? on Mar 18, 2024.

This story was originally published by Canary Media.

You might consider heat pumps to be a tantalizing climate solution (they are) and one you could adopt yourself (plenty have). But perhaps you’ve held off on getting one, wondering how much of a difference they really make if a dirty grid is supplying the electricity you’re using to power them — that is, a grid whose electricity is generated at least in part by fossil gas, coal, or oil.

That’s certainly the case for most U.S. households: While the grid mix is improving, it’s still far from clean. In 2023, renewable energy sources provided just 21 percent of U.S. electricity generation, with carbon-free nuclear energy coming in at 19 percent. The other 60 percent of power came from burning fossil fuels.

So do electric heat pumps really lower emissions if they run on dirty grid power?

The answer is an emphatic yes. Even on a carbon-heavy diet, heat pumps eliminate tons of emissions annually compared to other heating systems.

The latest study to hammer this point home was published in Joule last month by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. The team modeled the entire U.S. housing stock and found that, over the appliance’s expected lifetime of 16 years, switching to a heat-pump heater/AC slashes emissions in every one of the contiguous 48 states.

In fact, heat pumps reduce carbon pollution even if the process of cleaning up the U.S. grid moves slower than experts expect. The NREL team used six different future scenarios for the grid, from aggressive decarbonization (95 percent carbon-free electricity by 2035) to sluggish (only 50 percent carbon-free electricity by 2035, in the event that renewables wind up costing more than their current trajectories forecast). They found that depending on the scenario and level of efficiency, heat pumps lower household annual energy emissions on average by 36 percent to 64 percent — or 2.5 to 4.4 metric tons of CO2 equivalent per year per housing unit.

That’s a staggering amount of emissions. For context, preventing 2.5 metric tons of CO2 emissions is equivalent to not burning 2,800 pounds of coal. Or not driving for half a year. Or switching to a vegan diet for 14 months. And at the high end of the study’s range, 4.4 metric tons of CO2 is almost equivalent to the emissions from a roundtrip flight from New York City to Tokyo (4.6 metric tons).

Eric Wilson, senior research engineer at NREL and lead author of the study, told me, “I often hear people saying, ‘Oh, you should wait to put in a heat pump because the grid is still dirty.’” But that’s faulty logic. “It’s better to switch now rather than later — and not lock in another 20 years of a gas furnace or boiler.”

Emissions savings tend to be higher in states with colder winters and heaters that run on fuel oil, such as Maine, according to the study. (Maine seems to be one step ahead of the researchers: Heat pumps have proven so popular there that the state already blew past its heat-pump adoption goal two years ahead of schedule.)

A dirty grid, then, doesn’t cancel out a heat pump’s climate benefits. But heat pumps can generate emissions in the same way standard ACs do: by leaking refrigerant, the chemicals that enable these appliances to move around heat. Though it’s being phased down, the HVAC standard refrigerant R-410A is 2,088 times more potent a greenhouse gas than CO2, so even small leaks have an outsize impact.

Added emissions from heat-pump refrigerant leaks barely make a dent, however, given the emissions heat pumps avoid, the NREL team found. Typical leakage rates of R-410A increase emissions on average by only 0.07 metric tons of CO2 equivalent per year, shaving the overall savings of 2.5 metric tons by just 3 percent, Wilson said.

A 2023 analysis from climate think tank RMI further backs up heat pumps’ climate bona fides. Across the 48 continental states, RMI found that replacing a gas furnace with an efficient heat pump saves emissions not only cumulatively across the appliance’s lifetime, but also in the very first year it’s installed. RMI estimated that emissions prevented in that first year were 13 percent to 72 percent relative to gas-furnace emissions, depending on the state. (Canary Media is an independent affiliate of RMI.)

Both the RMI and NREL studies focused on air-source heat pumps, which, in cold weather, pull heat from the outdoor air and can be three to four times as efficient as gas furnaces. But ground-source heat pumps can be more than five times as efficient compared to gas furnaces — and thus unlock even greater greenhouse-gas reductions, according to RMI.

How much could switching to a heat pump lower your home’s carbon emissions? For a high-level estimate, NREL put out an interactive dashboard. In the “states” tab, you can filter down to your state, building type and heating fuel. For instance, based on a scenario of moderate grid decarbonization in my state of Colorado, a single-family home that swaps out a gas furnace for a heat pump could slash emissions by a whopping 6 metric tons of CO2.

You can also get an estimate from Rewiring America’s personal electrification planner, which uses more specific info about your home, or ask an energy auditor or whole-home decarbonization company if they can calculate emissions savings as part of a home energy audit.

One final takeaway Wilson shared: If every American home with gas, oil, or inefficient electric-resistance heating were to swap it right now for heat-pump heating, the emissions of the entire U.S. economy would shrink by 5 percent to 9 percent. That’s how powerful a decarbonizing tool heat pumps are.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Heat pumps slash emissions even if powered by a dirty grid on Mar 17, 2024.

This story was originally published by Yale Environment 360 and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

In August of 2021, rain fell atop the 10,551-foot summit of the Greenland ice cap, triggering an epic meltdown and a more-than-2,000-foot retreat of the snowline. The unprecedented event reminded Joel Harper, a University of Montana glaciologist who works on the Greenland ice sheet, of a strange anomaly in his data, one that suggested that in 2008 it might have rained much later in the season — in the fall, when the region is typically in deep freeze and dark for almost 24 hours a day.

When Harper and his colleagues closely examined the measurements they’d collected from sensors on the ice sheet those many years ago, they were astonished. Not only had it rained, but it had rained for four days as the air temperature rose by 30 degrees C (54 degrees F), close to and above the freezing point. It had warmed the summit’s firn layer — snow that is in transition to becoming ice — by between 11 and 42 degrees F (6 and 23 degrees C). The rainwater and surface melt that followed penetrated the firn by as much as 20 feet before refreezing, creating a barrier that would alter the flow of meltwater the following year.

All that rain is significant because the melting of the Greenland ice sheet — like the melting of other glaciers around the world — is one of the most important drivers of sea level rise. Each time a rain-on-snow event happens, says Harper, the structure of the firn layer is altered, and it becomes a bit more susceptible to impacts from the next melting event. “It suggests that only a minor increase in frequency and intensity of similar rain-on-snow events in the future will have an outsized impact,” he says.

Rain used to be rare in most parts of the Arctic: the polar regions were, and still are, usually too cold and dry for clouds to form and absorb moisture. When precipitation did occur, it most often came as snow.

Twenty years ago, annual precipitation in the Arctic ranged from about 10 inches in southern areas to as few as 2 inches or less in the far north. But as Arctic temperatures continue to warm three times faster than the planet as a whole, melting sea ice and more open water will, according to a recent study, bring up to 60 percent more precipitation in coming decades, with more rain falling than snow in many places.

Such changes will have a profound impact on sea ice, glaciers, and Greenland’s ice cap — which are already melting at record rates, according to Mark Serreze, director of the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colorado. The precipitation will trigger more flooding; an acceleration in permafrost thaw; profound changes to water quality; more landslides and snow avalanches; more misery for Arctic animals, many of which are already in precipitous decline due to the shifting climate; and serious challenges for the Indigenous peoples who depend on those animals.

Changes can already be seen. Thunderstorms are now spawning in places where they have historically been rare. In 2022, the longest thunderstorm in the history of Arctic observation was recorded in Siberia. The storm lasted nearly an hour, twice as long as typical thunderstorms in the south. Just a few days earlier, a series of three thunderstorms had passed through a part of Alaska that rarely experiences them.

Surface crevassing, which allows water to enter into the interior of the icecap, is accelerating, thanks to rapid melting. And slush avalanches, which mobilize large volumes of water-saturated snow, are becoming common: In 2016, a rain-on-snow event triggered 800 slush avalanches in West Greenland.

Rick Thoman, a climate scientist based at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, says that rainfall at any time of year has increased 17 percent in the state over the past half century, triggering floods that have closed roads and landslides that, in one case, sent 180 million tons of rock into a narrow fjord, generating a tsunami that reached 633 feet high — one of the highest tsunamis ever recorded worldwide.

But winter rain events are also on the rise. Where Fairbanks used to see rain on snow about two or three times a decade, Thoman says, it now occurs at least once in most winters. That’s a problem for local drivers because, with little solar heating, ice that forms on roads from November rains typically remains until spring.

The science of both rain and rain-on-snow events in the Arctic is in its infancy, and it is complicated by the fact that satellites and automated weather stations have a difficult time differentiating between snow and rain, and because there are not enough scientists on the ground to evaluate firsthand what happens when rain falls on snow, says Serreze.

It was hunters who first reported, in 2003, that an estimated 20,000 muskoxen had starved to death on Banks Island, in Canada’s High Arctic, following an October rain-on-snow event. It happened again in the winters of 2013-2014 and in 2020-2021, when tens of thousands of reindeer died on Siberia’s Yamal Peninsula.

In both places, the rain had hardened the snow and, in some places, produced ice, which made it almost impossible for the animals to dig down and reach the lichen, sedges, and other plants they need to survive the long winter.

Kyle Joly, a wildlife biologist with the U.S. National Park Service, views an increase in rain-on-snow events as yet another serious challenge for the world’s 2.4 million caribou, which have been in rapid decline pretty much everywhere over the past three generations. The ebbing numbers are a huge concern for northern Indigenous people who rely on caribou for food. Public health experts fear that Indigenous health will be seriously compromised if the animals can no longer be hunted.

Alaska’s western Arctic herd, which has been, at times, the largest in North America, had 490,000 animals in 2003 but just 152,000 in 2023. But at least that herd can still be hunted. In Canada’s central Arctic, the Bathurst herd has plummeted from roughly 470,000 animals in the 1980s to just 6,240 animals today; hunting those caribou in the Northwest Territories is currently banned.

Caribou are highly adaptable to extreme environmental variability, and their numbers can rise and fall for several reasons, according to Joly. The proliferation of biting flies in a warming climate can sap their energy, as can migration detours forced by the spread of roads and industrial development, and an increase in dumps of deep, soft snow, which are linked to the loss of sea ice. (An ice-free ocean surface increases humidity near the surface, which leads to more moisture in the atmosphere.)

Sharp-edged ice and crusty snow can also lacerate caribous’ legs, and rain on snow has periodically affected some of Alaska’s 32 caribou herds. For example, the day after Christmas in 2021, temperatures rose to more than 60 degrees F (15 degrees C) during a storm that dropped an inch of rain over a large area of the state. Alaska’s Fish and Game Department estimated that 40 percent of the moose, caribou, and sheep in the state’s interior perished that winter because they could not dig through the hard snow and ice.

It’s not just caribou and muskoxen that are being threatened. There is growing evidence that rain falling in parts of the Arctic where precipitation usually arrives as snow is killing peregrine falcon chicks, which have only downy feathers to protect them from the cold. Once water soaks their down, the chicks succumb to hypothermia.

Few scientists have evaluated the hydrological and geochemical impact of rain-on-snow events in polar desert regions, which are underlain by permafrost and receive very little snow in winter. Recent studies published by Queen’s University scientist Melissa Lafrenière and colleagues from several universities in Canada and the United States point to a worrisome picture unfolding at the Cape Bounty Arctic Watershed Observatory on Melville Island, in Canada’s High Arctic, which has been in operation since 2003.

A shift from runoff dominated by snowmelt in spring and summer to runoff from both rain and snowmelt is accelerating permafrost thaw and ground slumping, and it’s filling fish-bearing lakes with sediments. One study found a fiftyfold increase in turbidity in one lake that led to a rise in mercury and a decrease in the health of Arctic char, a fish that the Inuit of the Arctic rely on.

Lafrenière says that with only 20 years of measurement, it’s difficult to point conclusively to a trend. “But we have been seeing more rain falling in bigger events, in late summer especially. In 2022, we had unusually heavy rain that dropped an average summer’s worth of rain in less than 48 hours.”

To help scientists and decisionmakers better understand the impacts of what is happening, Serreze and his colleagues have created a database of all known rain-on-snow events across the Arctic. And increasingly, scientists like Robert Way of Queen’s University in Canada are working with the Inuit and other northern Indigenous people to ground-truth what they think the satellites and automated weather stations are telling them and to share the data that they are collecting and evaluating.

Way, who is of Inuit descent, was a young man when he witnessed parts of the George River herd, one of the world’s largest caribou herds, migrate across the ice in central Labrador. “There were thousands and thousands and thousands of them,” he recalls with wonder. The herd contained 750,000 animals in the 1980s; today, it has no more than 20,000. The animals are facing the same climate change challenges that caribou everywhere are facing.

Way is working with Labrador’s Inuit to better understand how these weather events will affect caribou and food security, as well as their own travel on snow and ice. But, he says, “It’s increasingly difficult to do this research in Canada because half of the weather stations have been shut down” due to federal budget cuts. Most of the manually operated stations, Way adds, “are being replaced by automated ones that produce data that makes it hard for scientists to determine whether it is raining or snowing when temperatures hover around the freezing mark.”

To better understand how rain-on-snow events are affecting the Arctic, Serreze says, researchers need to better understand how often and where these events occur, and what impact they have on the land- and seascape. “Satellite data and weather models can reveal some of these events, but these tools are imperfect,” he says. “To validate what is happening at the surface and the impacts of these events on reindeer, caribou, and musk oxen requires people on the ground. And we don’t have enough people on the ground.” Researchers need to work with Indigenous people “who are directly dealing with the effects of rain on snow,” he noted.

In 2007, Serreze stated in a University of Colorado Boulder study that the Arctic may have reached a climate-change tipping point that could trigger a cascade of events. More rain than snow falling in the Arctic is one such event, and he expects more surprises to come. “We are trying to keep up with what is going on,” he says, “but we keep getting surprised.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Rain comes to the Arctic, with a cascade of troubling changes on Mar 16, 2024.

California is not on track to meet its greenhouse gas emissions reduction goal for 2030, new data released by nonprofit think tank Next 10 and prepared by consulting firm Beacon Economics reveals.

To do so, the state must triple its annual emissions reductions, the 2023 California Green Innovation Index said.

“The increase in emissions following the pandemic makes it all the more difficult for California to meet its climate goals on time,” said Next 10 Founder F. Noel Perry, as reported by ESG News. “In fact, we may be further behind than many people realize. If you look at the trajectory since 2010, California won’t meet our 2030 climate goal until 2047. We need to triple the rate of decarbonization progress each year to hit that target.”

A recent jump in emissions from in-state power generation has been offsetting progress in the transportation sector, the report said.

California Air Resources Board (CARB) data shows that the state’s yearly greenhouse gas emissions increased 3.4 percent in 2021, while an early estimate by CARB shows emissions began decreasing the following year.

The new report said the promotion of zero-emissions vehicles (ZEVs) and buildings, as well as renewable sources of energy, must be accelerated to meet California’s goal of reducing emissions to 40 percent of 1990 levels by the end of the decade. To achieve this, the state would need to move from an average yearly reduction of roughly 1.5 percent to about 4.6 percent. However, as 2023 emissions data is not yet available, the percentage may be higher.

“California is an important state to study decarbonization because the state has a great deal of technology and wealth,” said Stafford Nichols, Beacon Economics research manager, as Reuters reported. “If California can’t decarbonize its economy then that does not bode well for less well-off economies.”

However, the prognosis for California’s greening economy has significant upsides. Of the 50 states, California is in third place for lowest per-capita emissions, after New York and Massachusetts. Additionally, the state economy’s carbon intensity — emissions versus gross domestic product — has fallen by half in the past two decades.

Transportation emissions in California — which went up 7.4 percent from 2020 to 2021 — make up almost 40 percent of its carbon footprint. Overall emissions from heavy-duty trucks, cars and other vehicles went down more than 10 percent from 2019 to 2021, which illustrates the state’s success in reducing its biggest pollution source. Heavy-duty vehicle emissions fell 14.1 percent from 2018 to 2021.

“While California is moving in the right direction in many ways, renewable electricity generation must greatly increase in the coming years in order to reach the state’s goal,” Nichols said, as reported by ESG News. “To meet our upcoming target of 50% of electricity from renewable sources by 2026, we need to double the speed we are adding RPSeligible renewables to our power mix, from 4.3% per year to 8.7% per year.”

ZEVs made up one-quarter of all new vehicle sales last year, an all-time high for the state. California also reached its 2025 ZEV onroad goal of 1.5 million in April of 2023, two years ahead of target. If the trajectory stays the same, it will meet its five million ZEV target for 2030 a year early.

A new goal for decarbonization of the power sector was adopted by the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) in February 2024. It calls for a 58 percent reduction in emissions by 2035, as compared to 2020 levels. In order to achieve the goal, the state needs to lower power emissions by 6.3 percent yearly from 2021 to 2035, according to Beacon Economics — almost twice the 3.5 percent average rate from 2011 to 2021. From 2020 to 2021, there was an upward trend of 4.8 percent.

For decades, California led rooftop solar, but new CPUC changes relating to solar generation compensation greatly reduced residential installation of solar panels. Currently, there are 1.8 million installations in the state with a generating power of 15-plus gigawatts running at peak capacity. However, there has been a 66 to 83 percent reduction in applications for residential rooftop solar since the new rules took effect in April of 2023.

Another challenge is that industrial wind and solar projects are finding it difficult to connect to the grid due to many of the transmission lines being at capacity or not being able to connect to renewable power installations in remote areas. An average project built in 2022 had to wait five years to be up and running after the initial interconnection request.

“While California is well-positioned as a leader on climate, there are substantial obstacles to accelerating our decarbonization efforts in an equitable way that benefits all Californians,” Perry said, as ESG News reported. “These are not insurmountable, but we need to act urgently in order to achieve these goals on time.”

The post California Must Triple Its Rate of Carbon Emissions Reductions to Reach 2030 Target, Report Says appeared first on EcoWatch.

In the past eight years, the Great Barrier Reef — the largest coral reef in the world, stretching 1,429 miles — has experienced five mass bleaching events, tied by scientists to climate change.

Most recently, corals around six islands in Turtle Group National Park, located about 6.2 miles off Australia’s Queensland Coast, have seen extensive bleaching, according to scientists from James Cook University, as reported by Reuters.

“It was quite devastating to see just how much bleaching there was, particularly in the shallows… (but) they were all still at the stage of bleaching where they could still recover as long as the water temperatures decline in time,” Maya Srinivasan, lead researcher of the survey, told Reuters.

Warming sea surface temperatures cause corals to expel the beneficial, colorful algae that live in them while providing them with food, causing the corals to turn white. If ocean waters cool in time, bleached corals may recover, but if temperatures stay elevated long enough, the corals will die.

The researchers carried out aerial surveys of more than 300 reefs and found that most had “prevalent shallow water coral bleaching,” CNN reported. According to the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, ongoing surveys in the water that can gauge the depth and severity of bleaching were also being conducted.

“We now need to combine the spatial coverage captured from the air with in-water surveys to assess the severity of coral bleaching in deeper reef habitats across the different regions of the Marine Park,” said Dr. Neal Cantin, Australian Institute of Marine Science senior research scientist, as reported by The Guardian.

Srinivasan said data collected from the six Turtle Group islands would be used in an ongoing analysis of the ways in which corals are impacted by bleaching, floods and cyclones, Reuters reported.

“The Reef has demonstrated its capacity to recover from previous coral bleaching events, severe tropical cyclones, and crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks,” the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority said, as reported by CNN.

The Australian Climate Council, an independent climate change communication organization, said the Great Barrier Reef’s sudden shifts point to larger risks for the UNESCO World Heritage Site, according to Reuters.

“With climate change where there’s predictions that these sorts of disturbance events will become more frequent and be of higher intensity… it’s becoming even more crucial than ever to have these long-term monitoring programs continue into the future,” Srinivasan added.

Simon Bradshaw, Climate Council’s research director, described the current bleaching event as “an underwater bushfire.”

“Climate change is the biggest risk not just to the Great Barrier Reef in Australia but also to coral reefs around the world,” said Tanya Plibersek, Australia’s environment minister, as CNN reported. “We know that we need to give our beautiful reef the best chance of survival for the planet and animals that call it home, for the 64,000 people whose livelihoods depend on reef tourism.”

The post ‘An Underwater Bushfire’: Major Coral Bleaching Event in Northern Parts of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef appeared first on EcoWatch.

The National Park Foundation (NPF) and National Park Service (NPS) recently announced that Yellowstone National Park has received a $40 million donation. The money is earmarked for improving existing housing and expanding housing for the park’s staff.

The gift was given by an anonymous donor, as NPR reported. The money will help provide affordable housing to the Yellowstone National Park staff, which can total more than 3,000 workers at the busiest times of the year.

A Yellowstone National Park seasonal employee housing trailer on April 9, 2019. Jacob w. Frank / NPS

“This transformational gift will meet a critical need for new housing in Yellowstone, and be a catalyst for more philanthropic investment,” Will Shafroth, President and CEO of NPF, said in a press release. “These skilled, dedicated professionals at the National Park Service who protect our parks and make visitors’ experiences great deserve housing they can be proud to call home.”

Like many parts of the U.S., areas around national parks have been impacted by rising housing costs, according to NPS. Further, homes converted into short-term rental units have limited the amount of housing available in the areas around national parks. This has pushed many workers to live farther away from the parks or quit working at the parks altogether. It has also made it harder to recruit new employees, NPS said.

NPF and NPS will use the funds to build more than 70 new modular housing units. The housing will be built in West Yellowstone and Gardner Village, as Cache Valley Daily reported. Construction is expected to begin later this year, NPS said.

In 2020, Yellowstone announced a major effort to improve employee housing and began replacing old trailers with new modular cabins. According to the press release, “The $40 million gift will bridge the funding gap at Yellowstone National Park to meet the current need for employees housing in the park and provide a funding model to accelerate construction of employee housing at national parks across the country.”

Above: A Yellowstone employee housing site before demolition, on Feb. 4, 2020. Below: New homes for park employees under construction on Oct. 8, 2021. Jacob w. Frank / NPS

“This gift will be transformational in helping us continue improving employee housing across Yellowstone,” Yellowstone National Park Superintendent Cam Sholly said. “Our thanks to the donors for their generosity and commitment to meet the needs of park employees and to the Park Foundation for its leadership and continued partnership.”

Yellowstone National Park is just one of many national parks facing a shortage in affordable housing for staff. NPS employs a total of about 20,000 people, and 15,600 workers rely on park housing. NPS stated it has more than 5,600 housing facilities, which include cabins, dorms and duplexes. But the organization noted that private philanthropy, like the $40 million donation to Yellowstone National Park, could quickly aid in efforts to improve and add housing at parks around the U.S.

“The housing challenges facing each park are unique, and so are the solutions,” said Chuck Sams, director of NPS. “The ability to recruit and retain a talented workforce remains essential to our ability to protect parks and to ensure a world-class visitor experience. NPS is committed to innovative solutions that contribute to meeting the demand for employee housing across the National Park System. I am incredibly grateful to the donors to the National Park Foundation whose tremendous generosity will help NPS address this critical need.”

The post Yellowstone National Park Receives $40 Million Donation for Employee Housing appeared first on EcoWatch.

This week’s quote is from author Michael Pollan: “The garden suggests there might be a…

The post Earth911 Inspiration: Meet Nature Halfway appeared first on Earth911.

Up to 10 informants managed by the FBI were embedded in anti-pipeline resistance camps near the Standing Rock Sioux Indian Reservation at the height of mass protests against the Dakota Access pipeline in 2016. The new details about federal law enforcement surveillance of an Indigenous environmental movement were released as part of a legal fight between North Dakota and the federal government over who should pay for policing the pipeline fight. Until now, the existence of only one other federal informant in the camps had been confirmed.

The FBI also regularly sent agents wearing civilian clothing into the camps, one former agent told Grist in an interview. Meanwhile, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, or BIA, operated undercover narcotics officers out of the reservation’s Prairie Knights Casino, where many pipeline opponents rented rooms, according to one of the depositions.

The operations were part of a wider surveillance strategy that included drones, social media monitoring, and radio eavesdropping by an array of state, local, and federal agencies, according to attorneys’ interviews with law enforcement. The FBI infiltration fits into a longer history in the region. In the 1970s, the FBI infiltrated the highest levels of the American Indian Movement, or AIM.

The Indigenous-led uprising against Energy Transfer Partners’ Dakota Access oil pipeline drew thousands of people seeking to protect water, the climate, and Indigenous sovereignty. For seven months, participants protested to stop construction of the pipeline and were met by militarized law enforcement, at times facing tear gas, rubber bullets, and water hoses in below-freezing weather.

After the pipeline was completed and demonstrators left, North Dakota sued the federal government for more than $38 million — the cost the state claims to have spent on police and other emergency responders, and for property and environmental damage. Central to North Dakota’s complaints are the existence of anti-pipeline camps on federal land managed by the Army Corps of Engineers. The state argues that by failing to enforce trespass laws on that land, the Army Corps allowed the camps to grow to up to 8,000 people and serve as a “safe haven” for those who participated in illegal activity during protests and caused property damage.

In an effort to prove that the federal government failed to provide sufficient support, attorneys deposed officials leading several law enforcement agencies during the protests. The depositions provide unusually detailed information about the way that federal security agencies intervene in climate and Indigenous movements.

Until the lawsuit, the existence of only one federal informant in the camps was known: Heath Harmon was working as an FBI informant when he entered into a romantic relationship with water protector Red Fawn Fallis. A judge eventually sentenced Fallis to nearly five years in prison after a gun went off when she was tackled by police during a protest. The gun belonged to Harmon.

Manape LaMere, a member of the Bdewakantowan Isanti and Ihanktowan bands, who is also Winnebago Ho-chunk and spent months in the camps, said he and others anticipated the presence of FBI agents, because of the agency’s history. Camp security kicked out several suspected infiltrators. “We were already cynical, because we’ve had our heart broke before by our own relatives,” he explained.

“The culture of paranoia and fear created around informants and infiltration is so deleterious to social movements, because these movements for Indigenous people are typically based on kinship networks and forms of relationality,” said Nick Estes, a historian and member of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe who spent time at the Standing Rock resistance camps and has extensively researched the infiltration of the AIM movement by the FBI. Beyond his relationship with Fallis, Harmon had close familial ties with community leaders and had participated in important ceremonies. Infiltration, Estes said, “turns relatives against relatives.”

Less widely known than the FBI’s undercover operations are those of the BIA, which serves as the primary police force on Standing Rock and other reservations. During the NoDAPL movement, the BIA had “a couple” of narcotics officers operating undercover at the Prairie Knights Casino, according to the deposition of Darren Cruzan, a member of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma who was the director of the BIA’s Office of Justice Services at the time.

It’s not unusual for the BIA to use undercover officers in its drug busts. However, the intelligence collected by the Standing Rock undercovers went beyond narcotics. “It was part of our effort to gather intel on, you know, what was happening within the boundaries of the reservation and if there were any plans to move camps or add camps or those sorts of things,” Cruzan said.

A spokesperson for Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, who oversees the BIA, also declined to comment.

According to the deposition of Jacob O’Connell, the FBI’s supervisor for the western half of North Dakota during the Standing Rock protests, the FBI was infiltrating the NoDAPL movement weeks before the protests gained international media attention and attracted thousands. By August 16, 2016, the FBI had tasked at least one “confidential human source” with gathering information. The FBI eventually had five to 10 informants in the protest camps — “probably closer to 10,” said Bob Perry, assistant special agent in charge of the FBI’s Minneapolis field office, which oversees operations in the Dakotas, in another deposition. The number of FBI informants at Standing Rock was first reported by the North Dakota Monitor.

According to Perry, FBI agents told recruits what to collect and what not to collect, saying, “We don’t want to know about constitutionally protected activity.” Perry added, “We would give them essentially a list: ‘Violence, potential violence, criminal activity.’ To some point it was health and safety as well, because, you know, we had an informant placed and in position where they could report on that.”

The deposition of U.S. Marshal Paul Ward said that the FBI also sent agents into the camps undercover. O’Connell denied the claim. “There were no undercover agents used at all, ever.” He confirmed, however, that he and other agents did visit the camps routinely. For the first couple months of the protests, O’Connell himself arrived at the camps soon after dawn most days, wearing outdoorsy clothing from REI or Dick’s Sporting Goods. “Being plainclothes, we could kind of slink around and, you know, do what we had to do,” he said. O’Connell would chat with whomever he ran into. Although he sometimes handed out his card, he didn’t always identify himself as FBI. “If people didn’t ask, I didn’t tell them,” he said.

He said two of the agents he worked with avoided confrontations with protesters, and Ward’s deposition indicates that the pair raised concerns with the U.S. marshal about the safety of entering the camps without local police knowing. Despite its efforts, the FBI uncovered no widespread criminal activity beyond personal drug use and “misdemeanor-type activity,” O’Connell said in his deposition.

The U.S. Marshals Service, as well as Ward, declined to comment, citing ongoing litigation. A spokesperson for the FBI said the press office does not comment on litigation.

Infiltration wasn’t the only activity carried out by federal law enforcement. Customs and Border Protection responded to the protests with its MQ-9 Reaper drone, a model best known for remote airstrikes in Iraq and Afghanistan, which was flying above the encampments by August 22, supplying video footage known as the “Bigpipe Feed.” The drone flew nearly 281 hours over six months, costing the agency $1.5 million. Customs and Border Protection declined a request for comment, citing the litigation.

The biggest beneficiary of federal law enforcement’s spending was Energy Transfer Partners. In fact, the company donated $15 million to North Dakota to help foot the bill for the state’s parallel efforts to quell the disruptions. During the protests, the company’s private security contractor, TigerSwan, coordinated with local law enforcement and passed along information collected by its own undercover and eavesdropping operations.

Energy Transfer Partners also sought to influence the FBI. It was the FBI, however, that initiated its relationship with the company. In his deposition, O’Connell said he showed up at Energy Transfer Partners’ office within a day or two of beginning to investigate the movement and was soon meeting and communicating with executive vice president Joey Mahmoud.

At one point, Mahmoud pointed the FBI toward Indigenous activist and actor Dallas Goldtooth, saying that “he’s the ring leader making this violent,” according to an email an attorney described.

Throughout the protests, federal law enforcement officials pushed to obtain more resources to police the anti-pipeline movement. Perry wanted drones that could zoom in on faces and license plates, and O’Connell thought the FBI should investigate crowd-sourced funding, which could have ties to North Korea, he claimed in his deposition. Both requests were denied.

O’Connell clarified that he was more concerned about China or Russia than North Korea, and it was not just state actors that worried him. “If somebody like George Soros or some of these other well-heeled activists are trying to disrupt things in my turf, I want to know what’s going on,” he explained, referring to the billionaire philanthropist, who conspiracists theorize controls progressive causes.

To the federal law enforcement officials working on the ground at Standing Rock, there was no reason they shouldn’t be able to use all the resources at the federal government’s disposal to confront this latest Indigenous uprising.

“That shit should have been crushed like immediately,” O’Connell said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline FBI sent several informants to Standing Rock protests, court documents show on Mar 15, 2024.