This story was produced in partnership with Atlanta News First.

Thousands of warehouse workers across the U.S. are likely regularly exposed to the cancer-linked chemical ethylene oxide. More than half of the country’s medical equipment is sterilized with the compound, which the EPA considers a carcinogen. Ethylene oxide evaporates off the surface of these medical products after they’ve been sterilized, creating potentially dangerous concentrations of air pollution in the buildings where they’re stored.

By and large, the EPA does not regulate these buildings — in fact, regulators don’t even know where most of them are. The Office of Safety and Health Administration, the federal agency in charge of worker protection that is known by its acronym, OSHA, has also done relatively little to evaluate worker exposure in these warehouses. But last week, OSHA opened a new investigation into a Georgia warehouse that stores medical devices sterilized with ethylene oxide, raising questions about whether the federal government is beginning to respond more quickly to these risks.

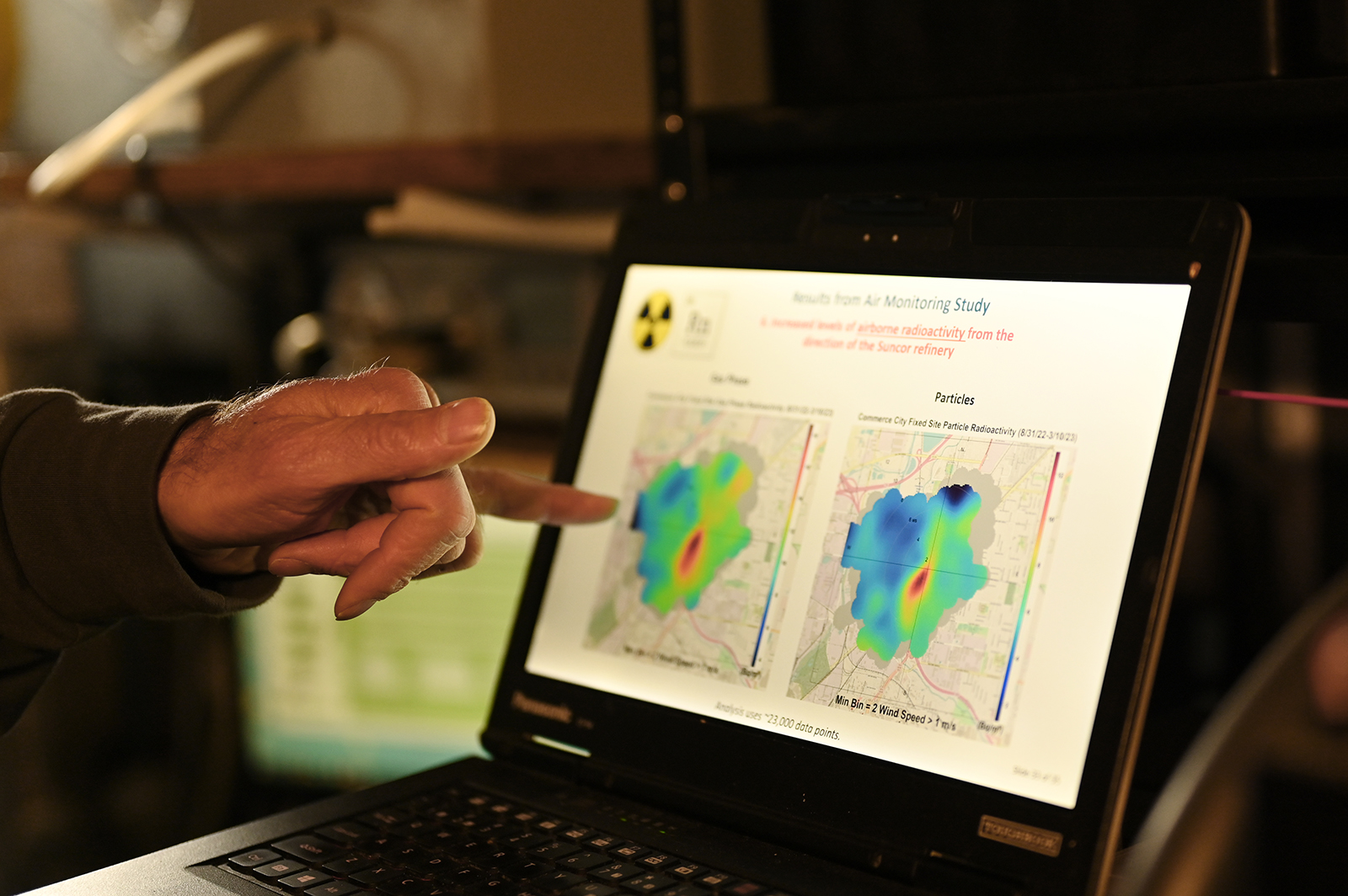

On March 13, the U.S. Marshals Service and the Douglas County sheriff’s office assisted OSHA in executing a search warrant at a warehouse leased by the medical device company ConMed in Lithia Springs, 17 miles west of Atlanta. The surprise inspection was initiated almost two weeks after a Grist and Atlanta News First investigation revealed that workers employed by ConMed had been unknowingly exposed to the chemical. Ambulances were routinely called to the facility as workers convulsed from seizures, lost consciousness, and had trouble breathing.

The workers sued the company in 2020, but the lawsuit was ultimately dropped earlier this year after a judge dismissed some of their claims, citing state labor laws. (Under Georgia law, once employees seek workers’ compensation from the state, they are barred from suing employers separately.) ConMed denies the lawsuit’s allegations that it knowingly exposed workers to ethylene oxide and maintains that no individual medical emergency can be tied to exposure to the chemical. A company representative told Grist that it is “committed to fully complying” with all applicable regulations and conducts monthly ethylene oxide testing for its employees to review.

“Given our many years of full cooperation with OSHA, as well as the fact that OSHA has inspected our Lithia Springs facility five times since 2019, ConMed was surprised by the manner in which OSHA elected to inspect the facility on March 13,” a company representative told Grist in an email.

Ethylene oxide is a powerful fumigant, but it poses significant health risks and is linked to lung and breast cancers as well as diseases of the nervous system. Once medical devices are treated with ethylene oxide, the chemical continues to evaporate off the surface of the product as it moves through the supply chain. While the devices are trucked to warehouses, stored, and then shipped to hospitals, the products continue to quietly off-gas ethylene oxide, putting workers who come into contact with it at risk.

In a new rule it published last week, the EPA said that it will begin regulating toxic emissions from warehouses located on the same site as the sterilizer plants that actually apply the chemical. However, the agency argued that constraints stemming from the regulatory definition of the sterilization industry mean that offsite warehouses will be excluded from oversight. Even if the agency could clear that bureaucratic hurdle, it does not have “sufficient information to understand where these warehouses are located, who owns them, how they are operated, or what level of emissions potential they may have,” in the agency’s words.

What little the EPA knows about the threat from offsite warehouses was gleaned from a study conducted by state regulators in Georgia. That effort initially identified seven off-site warehouses and found that at least one of the state’s warehouses was emitting more ethylene oxide than the sterilization plant that first treats the medical products before sending them out for storage. Federal officials will begin gathering data on warehouses, according to the new EPA rule, and use it to determine whether a completely new regulation governing storage facilities should be developed. Such a process could take years, according to experts who spoke to Grist. All the while, warehouse workers across the country will continue to inhale ethylene oxide, in many cases without their knowledge.

“Up until eight years ago, a lot of people had no idea that the sterilizer facility, which looks like your regular office park facility, was poisoning them,” said Marvin Brown, an attorney with the environmental nonprofit Earthjustice. “Now we have this additional issue of these warehouses that are continuing to poison people, and most people have no idea that they live next to one or work at one.”

Brown and other experts Grist spoke to said the agency could take one of two approaches to regulating warehouses. It could expand the definition of regulated facilities under the sterilizer rule it finalized earlier this month, or it could create a new category of facilities that covers warehouses and develop a separate rule. Both come with challenges.

Reopening a new rule that has already been finalized is tricky, according to Scott Throwe, a former EPA enforcement official who worked on a number of rules that the EPA rolled out in the decade after amendments to the Clean Air Act were passed in 1990. “It’s a huge can of worms,” he said. “Once you open a rule, then you have to fix this and you have to fix this. It snowballs.”

Alternatively, the EPA could draft a new rule entirely, he added, but the agency is unlikely to do that either, because of the sheer amount of effort such a process would take. Throwe said that the EPA’s decision not to include offsite warehouse regulations in its new rule means that the agency doesn’t have either the time, the resources, or the will to tackle those emissions at this time.

“They’re going to declare victory on this one and move on,” he said. “They ain’t reopening that rule unless someone sues them.”

A spokesperson for the EPA said that the agency has an “incomplete list” of warehouses and that it has not conducted any risk assessments of them. As a next step, the agency expects to follow up with sterilization companies that did not provide detailed information about the location of their warehouses in response to a 2021 request. Once those responses are received, the agency plans to conduct emissions testing at some of the warehouses. If the agency decides to pursue a separate rule for warehouses, that process could take four to five years, the spokesperson said.

Getty Images

The rule governing medical sterilization facilities was one of the first industry-specific air quality regulations that the EPA ever crafted. In its amendments to the Clean Air Act in 1990, Congress published a list of 189 toxic air pollutants and asked the agency to develop regulations for each industry emitting at least one of them. Officials published the first standards for medical sterilizers in 1994 with little fanfare, according to Throwe. At the time, regulators and toxicologists were unaware of the true risks of ethylene oxide, which was used to fumigate a range of materials, from books to spices to cosmetics. With the new law giving the agency just a decade to craft dozens of new regulations, officials rushed the process, sacrificing the efficacy of some standards along the way.

“It was like drinking from a firehose,” Throwe said. “Unrealistic statutory deadlines became court-ordered deadlines.”

Drafting new regulations for a polluting industry, regulators quickly learned, was a lot of work. In addition to collecting and analyzing copious amounts of data on a particular type of plant’s emissions and configuration, officials had to consult engineering experts to understand what kinds of technologies they could ask companies to use to control their emissions. Decades later, the process for revising these regulations to better protect exposed communities is no different. It took the EPA almost a decade to publish its new sterilizer regulations, and it did so under a court-ordered due date after missing a previous deadline to update the rule. If the agency were to issue a new rule for warehouses, the time and resource commitment would be steep, Throwe said.

While the EPA is not responsible for worker safety, it has found a roundabout way to increase protections for those coming in close contact with ethylene oxide. Since ethylene oxide is a fumigant, the agency is also pursuing separate oversight under a federal pesticide law. The Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act requires the agency to evaluate pesticides every 15 years and determine where, how, and how much of a given pesticide may be used. In April, the EPA proposed a new set of requirements including reducing the amount of ethylene oxide used for sterilization and mandating that workers wear protective equipment while engaging in tasks where there is a high risk of exposure to the chemical. Since the law applies to all facilities where ethylene oxide is used — not just sterilization plants — warehouse workers could benefit from the requirements once it is finalized.

Some state and local agencies are proactively regulating warehouses themselves. After the Georgia Environmental Protection Division found that one warehouse was estimated to emit about nine times as much ethylene oxide as the facility that sterilized it, the agency began trying to find similarly dangerous warehouses. After scouring the internet and reaching out to companies, the agency identified four warehouses that were emitting more ethylene oxide than permitted under state law. The agency is now in the process of issuing permits and requiring controls for those facilities.

In Southern California, which has a large concentration of sterilization facilities, the local air quality regulator has included requirements for offsite warehouses in a rule that primarily targets sterilization plants. The rule categorizes warehouses into two tiers — those with an indoor space of 250,000 square feet or more and those with between 100,000 and 250,000 square feet. Depending on the size of the facility, the warehouses are subject to different reporting and monitoring requirements. In the course of developing the rule, the agency identified 28 warehouses that fall into one of these two tiers. The agency finalized the rule in December, and larger warehouses will be studied for a year to determine whether they emit significant amounts of ethylene oxide.

Editor’s note: Earthjustice is an advertiser with Grist. Advertisers have no role in Grist’s editorial decisions.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline A loophole in the EPA’s new sterilizer rule leaves warehouse workers vulnerable on Mar 22, 2024.