Meet journalist Esha Chhabra, who spent a decade exploring the world for examples of social…

The post Best of Earth911 Podcast: Author Esha Chhabra on the Work of Restoring Our World appeared first on Earth911.

Meet journalist Esha Chhabra, who spent a decade exploring the world for examples of social…

The post Best of Earth911 Podcast: Author Esha Chhabra on the Work of Restoring Our World appeared first on Earth911.

This story was originally published by Canary Media and is republished with permission.

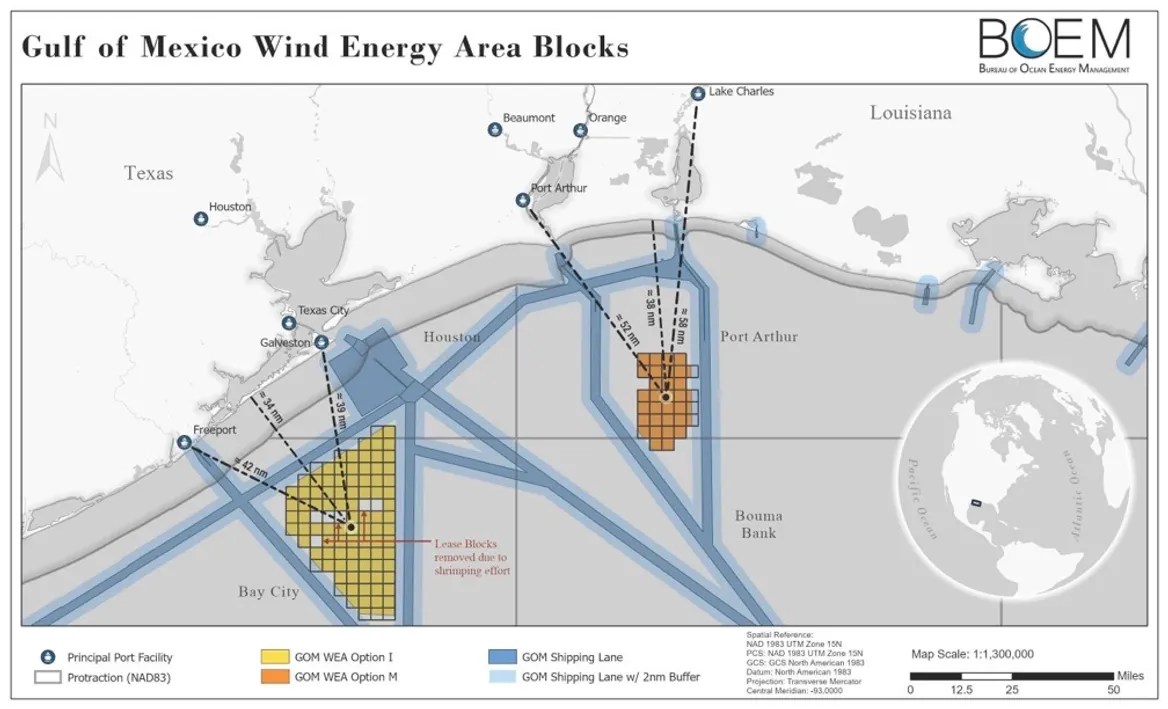

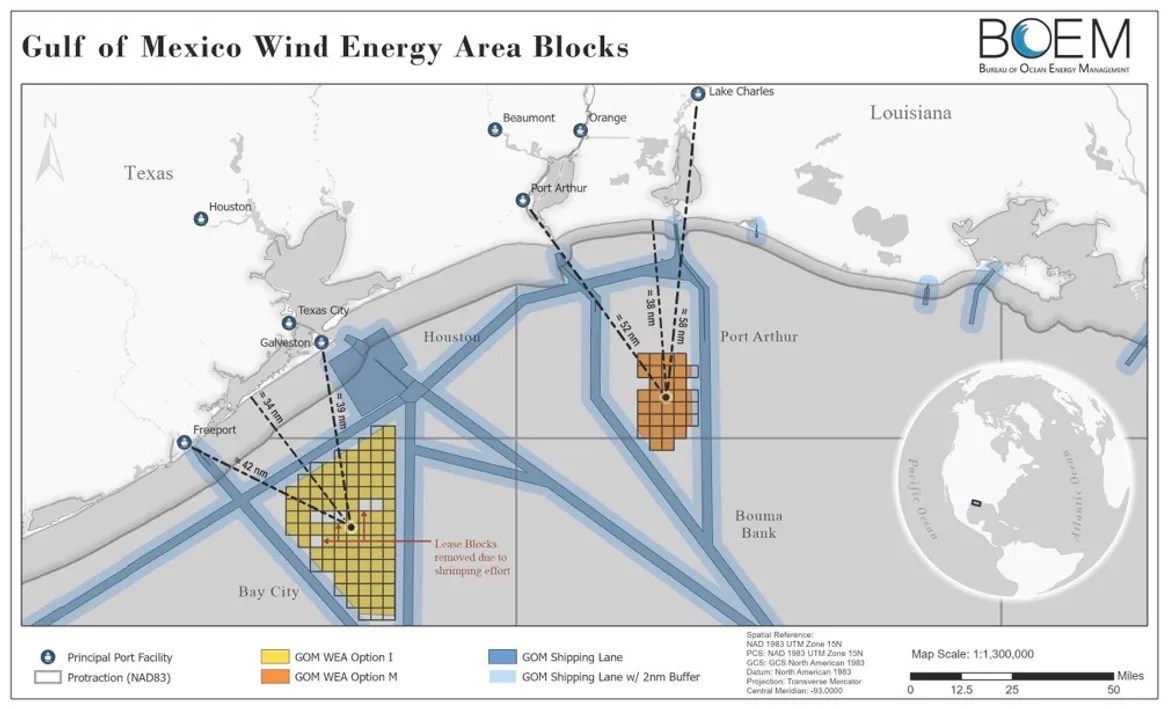

The Biden administration on Tuesday received a top bid of $5.6 million during the first-ever auction of offshore wind development rights in the Gulf of Mexico.

German energy giant RWE placed the highest bid for a 102,500-acre swath of water off the coast of Lake Charles, Louisiana, which has the potential to host 1.24 gigawatts’ worth of offshore wind capacity. Two other lease areas near Galveston, Texas didn’t receive any bids.

The lease sale is an important step toward building clean energy projects in a region that has long been dominated by offshore oil and gas production. Wind turbines are already spinning off the East Coast and more are being installed; meanwhile, floating offshore wind farms are being planned for California’s coastal waters. This week’s auction officially brings the emerging U.S. offshore wind industry to Gulf waters.

At the same time, the sale — which drew a lackluster response from the industry — reflects the significant challenges facing the offshore wind market in general, and the Gulf of Mexico in particular.

The U.S. Interior Department’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management put three areas up for auction that together span nearly 302,000 acres off the coasts of Texas and Louisiana. The combined lease area has the potential to generate roughly 3.7 gigawatts of clean electricity once developed, or enough to power nearly 1.3 million American homes — though the power generated by these projects could also eventually go toward producing green hydrogen.

“While today’s auction fell short of expectations, it is nonetheless a critical step for the energy transition on the Gulf Coast,” Josh Kaplowitz, vice president for offshore wind for the American Clean Power Association, an industry group, said on Tuesday in a statement.

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, the United States now has nearly 53 GW of offshore wind projects in the early planning, permitting or construction phases — over a thousand times greater than the current installed capacity of 42 megawatts (0.042 GW). The U.S. project pipeline is booming in large part due to state policies and federal targets for developing offshore wind, including the Biden administration’s goal of deploying 30 GW of the renewable energy source by 2030.

Yet it’s far from guaranteed that all projects in the expanding pipeline will get built.

Developers along the East Coast and worldwide are grappling with recent supply-chain bottlenecks, rising material costs and higher interest rates that have made it more expensive and less profitable to install giant offshore turbines in any location. Companies behind about 9.7 GW of proposed U.S. offshore wind farms are expected to renegotiate or outright cancel their existing power purchase agreements with utilities, according to BloombergNEF.

On top of those industry-wide constraints, offshore wind developers in the Gulf of Mexico must also confront lower-than-average wind speeds — which limit how much electricity the turbines can produce — and seasonal hurricane activity that threatens to topple infrastructure. And while Louisiana has set a nonbinding goal of generating 5 GW of offshore wind power by 2035, the region’s utilities and state agencies have done relatively little to put policies in place for offtaking all the clean electricity.

“The business case in the Gulf of Mexico for offshore wind is very vague, and very uncertain,” Chelsea Jean-Michel, a wind analyst at BNEF, recently told Heatmap.

John Begala of the Business Network for Offshore Wind told Canary Media ahead of Tuesday’s auction that participants would have a “strategic vision” that looks beyond the current challenges to see the long-term market value of Gulf Coast projects.

That could eventually include supplying electricity to help produce hydrogen at facilities across Louisiana and Texas. Last week, the hydrogen production company Monarch Energy said it was exploring building a $426 million plant in Louisana’s Ascension Parish. The facility would use electrolyzers to split water into hydrogen and oxygen — a process that requires using massive amounts of clean energy to be considered “green.”

Large energy companies like RWE are also well-positioned to create new turbine technologies that can perform well in the region, said Begala, who is the network’s vice president for federal and state policy. Shell, for example, has invested $10 million in Gulf Wind Technology to build an “accelerator” hub in Louisiana that will develop offshore wind products optimized for the Gulf.

Slow winds and hurricanes “are environmental conditions that are found throughout the world,” he said. “If Gulf of Mexico [developers] can figure out these twin challenges, you’re going to see that technology explode worldwide, and it’s going to have a major impact on global production,” he predicted.

Putting towering turbines in the Gulf would also boost the region’s own emerging offshore wind economy. At shipyards in Louisiana and Texas, hundreds of workers are already busy building specialized vessels for installing turbines and substations that help bring offshore wind energy to the onshore grid.

Environmental-justice groups said they welcomed this week’s offshore wind auction, citing the urgent need to replace heavily polluting fossil fuel projects with new industries that can ideally benefit the communities that have long suffered from poor air quality, a degraded environment and, increasingly, rising sea levels and other consequences of a warming planet.

But environmentalists also expressed disappointment that BOEM didn’t include incentives for developers to create “community benefit agreements” in the lease terms, as the agency did in California’s offshore wind auction last year. These legal agreements stipulate the terms a developer agrees to provide — including workforce development opportunities and other economic contributions — in exchange for earning the local community’s support. The lease terms do offer a 10 percent credit to developers who contribute to a fisheries compensation fund for commercial fishing outfits, but nothing similar for communities.

“The Gulf South is uniquely vulnerable to both [oil and gas] pollution and to climate impacts, and so we expected to see the same — if not more — benefits headed to the region,” said Kendall Dix, the national policy director for the nonprofit organization Taproot Earth.

Still, he added, local communities will potentially have another opportunity to advocate for and negotiate such terms when developers and utilities forge power purchase agreements in the coming years, or when BOEM opens additional swaths of the Gulf of Mexico to offshore wind development.

“The [Biden] administration has been saying that they want to make justice a priority,” he said. “I just think that the moment calls for something bigger.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Why the Gulf of Mexico’s first offshore wind auction wasn’t a smash hit on Sep 3, 2023.

This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Global Indigenous Affairs Desk.

A 54-year-old climate activist who was among hundreds of peaceful protesters criminalized for opposing the construction of an oil pipeline through pristine Indigenous lands is facing up to five years in prison, amid growing alarm at the crackdown on legitimate environmental protests.

Mylene Vialard was arrested in August 2021 while protesting in northern Minnesota against the expansion and rerouting of Line 3 – a 1,097-mile tar sands oil pipeline with a dismal safety record, that crosses more than 200 water bodies from Alberta, Canada, to refineries in the US midwest.

Vialard was charged with felony obstruction and gross misdemeanor trespass on critical infrastructure after attaching herself to a 25-foot bamboo tower erected to block a pumping station in Aitkin county. The gross misdemeanor charge, a post 9/11 law which has been used widely against protesters, was eventually dismissed after a court ruled there was insufficient evidence.

Vialard refused to take a plea deal on the felony charge, and her trial opened in Aitkin county on Monday.

“It was kind of a torturous decision. But in the end, I couldn’t sign a piece of paper saying I was guilty because I’m not the guilty party here. Enbridge is guilty, the violation of treaty rights, the pollution, the risk to water, that is what’s wrong. I’m just using my voice to point out something that’s wrong,” said Vialard, a self-employed translator and racial justice activist from Boulder, Colorado.

“I’m preparing my house for the worst case scenario,” she added.

Vialard’s arrest was not an anomaly. Minnesota law enforcement – which along with other agencies received at least $8.6 million in payments from the Canadian pipeline company Enbridge – made more than 1,000 arrests between December 2020 and September 2021.

The protesters, who identified as water protectors, were arrested during non-violent direct actions across northern Minnesota as construction of the 330-mile line expansion jumped from site to site, in what campaigners say was a coordinated strategy to divide and weaken the Indigenous-led social movement – an allegation Enbridge denies.

Overall, at least 967 criminal charges were filed including three people charged under the state’s new critical infrastructure protection legislation – approved as part of a wave of anti-protest laws inspired by the American Legislative Exchange Council (Alec), a rightwing group backed by fossil fuel companies.

Among those criminalized were a grandfather in his late 70s, numerous teenagers, first-time protesters and seasoned activists – many of whom travelled long distances amid growing anger and desperation at the government’s lack of urgency in tackling the climate emergency.

Yet the vast majority of charges were eventually dismissed – either outright by prosecutors and judges or through plea deals, suggesting the mass arrests were about silencing and distracting protesters, according to Claire Glenn, an attorney at the Climate Defense Project.

“It was obviously not about criminal sanctions or public safety because otherwise the prosecutors would not be dismissing these cases left and right. Enbridge was paying police to get people off the protest line and tied up with pretrial conditions, so they could get the pipeline in the ground, and it worked,” said Glenn, who has represented more than 100 Line 3 protesters including Vialard.

In a statement to the Guardian, Enbridge said the protesters were not arrested for peaceful protest but acted in ways that were “illegal and unsafe”, endangering themselves and others and causing damage.

Line 3 has a long track record of environmental disasters since it began operating in 1968, including a 1.7 million gallon spill at Grand Rapids, Minnesota, in 1991 which remains the largest inland oil leak in US history. Enbridge reduced its capacity amid growing concerns about the pipeline’s safety, but in 2014 announced a multibillion-dollar project to expand and partially reroute the pipeline.

Construction went ahead everywhere except Minnesota due to widespread opposition from tribal nations, some state agencies, and climate and environmental groups. But in late 2020, regulators granted the remaining permits, and construction began in freezing cold December as thousands of Americans were dying every week from Covid.

Vialard and her teenage daughter were among thousands of ordinary people from across the US to respond to Indigenous activists requesting help in protecting their sovereign territory and water sources.

“The video of Indigenous leaders calling on white people to show up and do what was necessary to protect the land was very moving. There’s been so much racism and so much abuse towards Indigenous people throughout history, that this felt like part of the work that we need to do,” Vialard said.

It wasn’t the first time an Indigenous-led movement garnered wider public support.

The huge 2016 gathering of tribes and allies defending Standing Rock Sioux territory from the Dakota Access pipeline captured the world’s attention, and inspired a global movement of resistance to fossil-fuel infrastructure projects. The protest was brutally policed but the tribe never backed down and succeeded in forcing an environmental impact study – which could eventually shut down the pipeline.

The Standing Rock success triggered a wave of new anti-protest laws and could explain why in Minnesota Enbridge made it difficult for activists – and the media – by constructing at multiple sites simultaneously, according to the attorney Glenn.

Vialard had supported Standing Rock from afar but Line 3, located more than 1,000 miles from Boulder, was her first experience of civil disobedience or direct action. The arrests were tough – but Vialard says that the environmental destruction she saw was even harder.

“People being arrested was the reality. But I was mostly worried about the destruction of pristine lands that I was witnessing. I went to the headwaters of the Mississippi, such an iconic gorgeous river full of rare species, and to turn around and see this big swath of destruction through the forest … that was really very moving to me, it just breaks my heart.”

The new Line 3 started transporting oil in October 2021.

Minnesota environmental regulators have confirmed four groundwater aquifer breaches along the new pipeline – including one last month in Aitkin county, not far from where Vialard was arrested, at a wild rice lake in an area with complex wetlands and peat bogs. Enbridge, which reported gross profits of $16.55 billion for the year ending June 2023, has so far been fined $11 million to address the breaches, which a spokesperson said “Enbridge reported transparently and corrected them consistent with plans approved by the agencies.”

Oil from tar sands is among the dirtiest and most destructive fossil fuels, emitting three times as much planet-heating pollution as conventional crude oil. Environmentalists say the Line 3 expansion was the equivalent of adding 38 million fossil fuel-powered vehicles to our roads.

Many of the Line 3 defendants – including Vialard’s daughter – opted for plea deals, but the legal wrangling still tied people up for months or years. Some were left with a criminal record while others were able to secure a “deferred adjudication” plea in exchange for the charge being erased after a probationary period that restricted their ability to protest, find work and travel.

Vialard’s is only the second felony case to reach the trial phase, but several other Line 3 cases remain open and a misdemeanor trial against 70-year-old Jill Ferguson also begins on Monday, in Clearwater county. Next month three Anishinaabe women elders – Winona LaDuke, Tania Aubid, and Dawn Goodwin – will go on trial together on gross misdemeanor critical infrastructure charges related to a January 2021 protest.

But the mass arrests and criminalization of Line 3 activists is part of a nationwide – and global – trend of suppressing legitimate protests about climate and environmental harms, according to Marla Marcum, director of the Climate Disobedience Centre, which supports climate activists engaged in civil disobedience in the US.

“The pattern of heavier and heavier criminalization is undeniable. It’s a tactic which aims to divide and distract activists, suppress dissent and stop ordinary folks getting involved as more and more people wake-up to the urgency of the situation … tying people up for years is a huge emotional and energy drag.”

Marcum says that most environmental activists are being charged with serious crimes from old statutes such as domestic terrorism and gross trespass.

Yet since 2017 45 states have passed or tried to pass new legislation that further restricts the right to protest, and which expands penalties for protesters. At least three states – Oklahoma, Iowa, and Florida – have passed legislation providing some impunity for those who injure protesters, according to the International Center for Not-For-Profit Law, which tracks anti-protest bills.

“When a protest movement is righteous, effective and powerful, the US government responds by trying to chill, deter and criminalize rather than engaging with the issue,” said Vera Eidelman, a staff attorney with the ACLU’s speech, privacy and technology project who focuses on the right to protest and free speech rights.

A spokesperson from Enbridge said: “Protesters were not arrested for peaceful protest. They were arrested for breaking the law. Illegal and unsafe acts by protesters endangered themselves, first responders and our workers. They also caused millions of dollars in damages … including to equipment owned by small businesses and Tribal contractors on the project. We support efforts to hold protesters accountable for their actions. Activists may attempt to position this as a global conspiracy. It isn’t.”

The past two years since the arrest have been difficult for Vialard, and fighting the criminal charges has cost a lot of time, energy and lost income, but she doesn’t regret answering the call for help from Indigenous leaders.

“I was born and raised in France, and was never taught about the people and wisdom being crushed and forgotten because of colonization. But there’s so much to learn from ancient wisdom and so much to unpack within ourselves … You don’t have to get arrested, but be brave and do something that’s valuable for your future, for your children and their children’s future. It’s so enriching.”

Last month, Vialard packed up her house and headed back to northern Minnesota to prepare for the trial among those who tried their best to stop the pipeline that is polluting waterways and warming the planet.

“I am preparing for the worst case scenario. Making this decision was not an easy one, but I feel like it’s our duty to to fight when the decisions being made are so wrong. There is pollution everywhere, climate change is a reality and yet the oil and gas industry is still destroying our planet. I’m just a regular person but it’s pretty crazy to me.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline ‘I’m not the guilty one’: the water protector facing jail time for trying to stop a pipeline on Sep 2, 2023.

In a major victory for the people of south Memphis, a plant that uses carcinogenic ethylene oxide to sterilize medical equipment announced this week that it is shutting down.

The decision by Sterilization Services of Tennessee follows more than a year of dogged organizing by residents and activists fed up with the industrial pollution that the company, and more than 20 others, releases into their community. Ethylene oxide, an odorless and colorless gas, has been linked to multiple forms of cancer.

“We’re relieved that the community will soon have one less polluting facility that they have to contend with,” Amanda Garcia, a senior attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center, told Grist.

The facility opened in 1976 and is the flagship of Sterilization Services, which also has locations in Atlanta and Richmond, Virginia. In a letter to U.S. Representative Steve Cohen, a Democrat whose district includes Memphis, company attorneys said the facility will move, but did not disclose further details.

Community members and advocates told Grist that Sterilization Services’ facilities is just one of more than 20 sources of toxic pollution in south Memphis, where more than 98 percent of residents are Black. Among the most toxic are a refinery owned by Valero and a steel mill owned by Nucor. A 2020 study from the University of Memphis found that the life expectancy of local residents is 10 years lower than that of their neighbors just a few miles away. KeShaun Pearson, president of Memphis Community Against Pollution, called the elimination of a major polluter an “extreme victory,” but said there is more work to be done.

“Black people have been relegated to places that are overburdened with pollution and cancer causing agents because of the zoning that has been approved for industry in those areas,” he said.

Cheryl Ballard, a lifelong resident of south Memphis, is happy to see the plant close, but wants to see air monitoring begin in the interim to ensure pollution levels do not exceed federal standards. Ethylene oxide is a colorless and odorless compound that, except in high concentrations, is difficult to detect without expensive equipment.

“Harm has already been done,” she said, noting that many residents have been exposed for 40 years.

Environmental regulators learned of the risks of medical equipment sterilization facilities in 2016, when the EPA found ethylene oxide to be 30 times more toxic to adults and 60 times more toxic to children than previously known. The finding was based on a series of studies in the early 2000s that linked ethylene oxide exposure to breast cancer in women and to lymphoma.

More than 50 percent of the nation’s medical equipment is sterilized with the chemical because it can fumigate heat-sensitive equipment without damage. In April, the EPA proposed revised regulations that it claims will reduce ethylene oxide emissions from these facilities by 80 percent. It will take more than a year for the new rule to go into effect.

According to the EPA, there are 86 medical sterilization facilities operating nationwide. In August 2022, regulators published the results of an analysis that found 23 of them, including the one in south Memphis, pose a cancer risk greater than 1 in 10,000 to nearby communities, a level that the agency considers unacceptable. That means that if 10,000 people were exposed to a certain level of the substance during their lives, one of them would be expected to develop cancer. According to a Grist analysis of agency data, the south Memphis plant is the seventh most toxic of its kind in the country.

In February, the Southern Environmental Law Center, on behalf of Memphis Community Against Pollution, asked the Shelby County Health Department to use its emergency powers under county and federal air pollution laws to address Sterilization Service’s carcinogenic emissions. According to Garcia, the agency argued it lacks the authority to compel the facility to address its emissions as long as it is in compliance with the federal Clean Air Act.

The situation highlights a recurring inconsistency in the nation’s air pollution laws: Companies can emit pollution at levels allowed by their permits yet generate cancer risk at levels that the federal government considers unacceptable. While environmental regulators have the authority to take emergency action against these emissions, they frequently do not. Historically, the EPA has largely used its emergency authority to address acute public health crises, such as a refinery in the Virgin Islands that rained oil on a nearby neighborhood.

Garcia said that the South Memphis case “highlighted serious concerns about the local air pollution control program.” The Shelby County Department of Health did not respond to a request for comment.

The Food and Drug Administration has expressed concern that closing sterilization facilities could upset the medical device supply chain and lead to dangerous shortages in hospital equipment. In a 2019 statement, Norman Sharpless, the agency’s acting commissioner at the time, said in a statement that a shortage “can be a detriment to public health.”

The agency has said that it is researching alternatives to ethylene oxide sterilization, but that the development and approval of those methods could take many years.

Naveena Sadasivam contributed to this story.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline ‘Extreme victory’: Years of organization leads to the shuttering of a toxic polluter in south Memphis on Sep 1, 2023.

A new study has found that only about 12% of people in the U.S. consume more than half of the beef eaten in the country on any given day. According to the researchers, the highest consumption was more likely to occur with men or people aged 50 to 65.

The researchers used the 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans as the baseline. Theses latest guidelines suggest 4 ounces combined of meat, poultry, and eggs for people consuming 2,200 calories per day, so they reviewed people consuming more than this.

Researchers analyzed data collected by the CDC in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and focused on beef consumption, noting that the beef industry in particular had major environmental impacts. The beef industry produces up to 10 times more emissions than chicken and over 50 times more emissions than beans.

The survey collected information of what more than 10,000 adults ate within a 24-hour period. The researchers were surprised to find that so much beef consumption was coming from a small percentage of people.

“On one hand, if it’s only 12% accounting for half the beef consumption, you could make some big gains if you get those 12% on board,” Diego Rose, corresponding and senior author of the study and professor and nutrition program director at Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, said in a statement. “On the other hand, those 12% may be most resistant to change.” Rose also noted that beef is high in saturated fat, which raises health concerns.

About one-third of beef consumption in a day came from steak, brisket, or other cuts of beef. Most of beef consumption came from what the researchers called mixed dishes, like burritos, burgers, or spaghetti with meat sauce.

With their findings, which were published in the journal Nutrients, the researchers hope to influence the 12% of people eating a disproportionate amount of beef to make switches to other, lower-emissions protein sources.

“If you’re getting a burrito, you could just as easily ask for chicken instead of beef,” said Amelia Willits-Smith, lead author of the study and a postdoctoral fellow at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Further, the study found that people below the age of 29, above the age of 66, or anyone who looked up the MyPlate method from the U.S. Department of Agriculture were least likely to eat disproportionate amounts of beef.

“This might indicate that exposure to dietary guidelines can be an effective tool in changing eating behaviors, but it could also be true that those who were aware of healthy or sustainable eating practices were also more likely to be aware of dietary guideline tools,” Willits-Smith said.

To conclude the study, the authors suggest that their findings should be used and expanded upon to encourage people in the U.S. to reduce beef consumption through campaigns and educational programs, ultimately to lessen the beef industry’s climate impacts.

The post Just 12% of People in the U.S. Consume Over 50% of the Country’s Beef, Study Finds appeared first on EcoWatch.

Pickleball, one of the fastest-growing sports in America, has gained immense popularity. However, pickleball players…

The post Recycling Mystery: Can I Recycle Pickeballs? appeared first on Earth911.

What do the response to climate change and the Y2K computer bug — which required…

The post Best of Earth911 Podcast: William Ulrich on Learning From Y2K To Design the Circular Economy appeared first on Earth911.

Today’s inspiration is from Mahatma Gandhi: “What we are doing to the forests of the…

The post Earth911 Inspiration: What We Are Doing to the Forests of the World appeared first on Earth911.

It’s a truth universally acknowledged that Americans love to stuff their faces with cow meat. There may be nothing more stereotypically American than grilling burgers on the Fourth of July. Meatloaf is a home-cooking classic. And few dishes in the country’s cookbook have the same cachet as steak or match the succulence of a barbecued brisket. In 2021, Americans ate 20 billion pounds of beef. That’s roughly 60 pounds per person, or a Big Mac every other day, plus a Whopper every three or four days. So it’s no wonder that the United States is the world’s top producer of veal and beef.

But this picture of the country’s beef consumption — a major factor in greenhouse gas emissions from U.S. agriculture, which accounts for about one-tenth of the country’s total — is more skewed than the raw numbers might lead you to believe. New research indicates that not all beef eaters are created equal. A small percentage of the country’s population — just 12 percent — accounts for half of the country’s beef consumption on any given day, according to a paper published on Wednesday in the journal Nutrients.

“It’s startling that it’s concentrated among a small minority,” said Diego Rose, a professor at Tulane University and a co-author of the paper.

From a climate standpoint, these beef guzzlers are not all that different from gasoline superusers — the 10 percent of drivers who account for one-third of the country’s gas use. A single cow can belch up to 264 pounds of methane in a year, the equivalent of burning almost 4,000 pounds of coal or driving a gas-powered car about 9,000 miles. That’s why climate advocates say people should eat less beef if they want to help ease climate change. “Beef is kind of like an environmentally extravagant source of protein,” Rose said. “It’s like the Hummer of the protein world.”

According to previous research by Rose and researchers at the University of Michigan, getting Americans to cut their beef consumption by 90 percent – and other animal products by 50 percent – would reduce emissions by the same amount as taking every single car off the road in the U.S., and another 200 million cars off the roads in other countries, for a year. The good news, in other words, is that the entire population of the United States doesn’t need to be convinced; a focus on changing the eating habits of the small group of beef eaters could go a long way.

Who, exactly, comprises that group? “There’s some of everybody,” Rose said, but men and people between the ages of 50 and 65 are most likely to be big beef eaters, the study found. The study doesn’t explain the gender gap, but other research has linked similar findings to a perception that meat is more masculine and to a conclusion that men’s spending habits are worse for the climate than women’s.

The meat-eating gap doesn’t end with gender. College graduates, young people, old people, and people familiar with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s dietary guidelines all tend to eat less beef, the study found. Past surveys have indicated that Republicans are more likely to eat meat (not just beef) than Democrats. And people with higher incomes tend to eat more meat at first but less meat over time compared to people in the low-income bracket.

It’s not clear whether telling people who eat a lot of beef that their eating habits are contributing to global warming would actually make them change their ways. Some research suggests it might. But many people who feel wrong about eating meat still eat a lot of it. Psychologists call this the “meat paradox.” That term originally denoted the cognitive dissonance associated with consuming animal flesh while feeling morally wrong about animal suffering. But the same mental gymnastics appear to be associated with beef consumption and climate change, too.

Still, that doesn’t mean that ethical arguments are ineffective, according to Peter Singer, the moral philosopher and animal rights advocate who has spent much of his life trying to convince people not to eat meat. In a recent article in the Atlantic, he wrote that meat eaters can be convinced that eating meat is wrong, but the effect of that persuasion “is felt most powerfully at the level of the policy changes that voters will support, rather than in people’s choice of what to buy at the supermarket.” Getting money and lobbyists out of politics would be a start, Singer wrote. While his article focused on animal welfare, it might as well have been about climate change. Top U.S. meat and dairy companies have spent millions of dollars trying to kill climate legislation.

Voters, consumers, and political and corporate leaders still seem far from convinced enough to take collective action to lower beef consumption. Arby’s has shunned plant-based meat and even teased critics with its “Marrot” — a carrot look-alike made from turkey meat. One of the main Republican talking points in opposition to the ambitious climate proposal known as the Green New Deal, which aimed to tackle agricultural emissions without mentioning cows, was: “They want to take away your hamburgers.” Two years ago, a fake story made the rounds alleging that President Joe Biden would limit Americans to one hamburger a month. In response, Representative Lauren Boebert, a Republican from Colorado, told the president to “stay out of my kitchen.”

Knowing that a small portion of Americans eat much of the country’s beef won’t make the political climate any less hostile. But it might help hone arguments about the benefits of eating less beef and the dangers of guzzling it.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Beef guzzlers: 12% of Americans eat half of the country’s cow meat on Sep 1, 2023.

When people think about “climate fiction,” they tend to imagine the speculative sci-fi of writers like Kim Stanley Robinson, or perhaps the eco-anxiety that pervades a book like Jenny Offill’s Weather. These are books where the visible effects of the climate crisis dominate the plot or at least the thought patterns of the characters. Lydia Kiesling’s Mobility, which came out last month, is a different kind of climate novel: It tells the story of a young woman who doesn’t think that much about the climate crisis at all, despite her ancillary role in causing it.

The protagonist, Bunny Glenn, works for a small, family-owned oil company, first as an administrative assistant and later as a public-relations executive focused on advancing the interests of “women in energy.” She only took the job because she couldn’t find a better one, and she feels vaguely that there’s something wrong with what she’s doing. Nevertheless, she doesn’t have any plans of quitting. In the words of Gillian Welch, she wants to do right, just not right now.

Though Mobility looks superficially like a story about one woman’s aimless young adulthood and middling professional career, the question of Bunny’s complicity in the destruction of the planet can’t help gushing up, complicating the book’s tale of class anxiety and alienation. Kiesling doesn’t force her preoccupation with climate change on the reader, but she does challenge them to look beyond Bunny’s blinkered consciousness and spot the two-way relationship between individual decisions and the slow progress of planetary collapse.

Kiesling’s first novel, The Golden State, narrates a 10-day span in the life of a young mother who moves out to the California high desert on her own to grapple with her new life as a mother. Right from the start, Mobility takes a different tack: Rather than a one-week snapshot of a young woman’s life, the novel charts that woman’s trajectory over the course of several decades, sweeping from the past through the present and into a not-too-distant future.

But if Mobility is a bildungsroman, it’s a somewhat uneventful one. The narrative opens on Bunny as a teenager in Baku, Azerbaijan, where her father has a Foreign Service posting. Diplomats and oil company officials have descended on the Central Asian nation, jockeying for a share of its all-important Caspian Sea petroleum, but Bunny isn’t thinking much about the “the aboveground oil pipes that snaked through the dirt roads and knobby paved streets” of Baku’s urban sprawl. She’s more focused on Eddie, the documentary filmmaker she has a crush on, and Charlie Kovak, a renegade journalist who looks a little too long in her direction.

The wax remains in Bunny’s ears until well into her twenties, by which time she has moved back in with her mother in Beaumont, Texas, a city home to the enormous Motiva oil refinery complex. Fresh off a breakup and stripped of career prospects thanks to the 2008 recession, she stumbles into doing administrative work for an engineering company, then moves over to the new “energy solutions” unit of a domestic oil company, which is starting to invest in solar and other non-fossil technologies. The oil company, privately held and family-run, comes off as a miniature version of Hunt, complete with a patriarchal executive who resembles industry titan H.L. Hunt. Bunny soon makes herself indispensable to that boss, Frank Turnbridge, whoʻs fond of saying that his company thinks in “geologic time.”

The contrast between individual human lives and larger economic and geological forces is omnipresent in the book, sometimes in Bunny’s thoughts and sometimes in more subtle aesthetic juxtaposition, such as when Bunny orders a chicken Caesar at a work lunch in Beaumont and looks out at a “golf course … pale with heat and refinery haze.” The three sections of the book are labeled “Upstream,” “Midstream,” and “Downstream,” oil industry terms for different stages of the production cycle, and each smaller chapter opens with the index price of U.S. crude oil in the year the chapter takes place. As a result, the reader is reminded that not only economies but also personal lives follow the movements of global commodity markets. By the same token, the “mobility” of the book’s title could refer to Bunnyʻs personal mobility through the class strata of Texas or the spatial mobility we gain by burning oil in cars and airplanes.

In addition to following Bunny’s entanglement with oil, the narrative also follows her evolution into a pathbreaker for professional women. During the first half of the book, we find her on the outside of conversations between more knowledgeable men, first the expat guys in Baku and then the oil buffs at parties in Houston. But by the end of the book Bunny is at an all-women roundtable at a big conference back in Baku, holding her own with other successful professionals from BP and the American embassy who are gathered together for “the promulgation of various agendas.”

Kiesling herself cares a lot about climate change — she’s written an essay about wildfire for the Wall Street Journal and volunteered with Portland mutual aid groups during that city’s heat wave — and Bunny serves as a kind of alternate version of her author. Sheʻs more or less the same age as Kiesling, and both came of age as the child of a prominent diplomat. But the two take very different paths through the labyrinth of millennial existence. Instead of becoming a writer with left-wing politics who lives in a liberal West Coast city, Bunny becomes a materialistic professional in Texas who talks to finance guys at boring weddings. (The descriptions of bourgeois Houston’s rooftop parties and ugly skyscrapers ring true, though one pities Bunny’s commitment to trying all of the cityʻs ethnic cuisines “in some small portion,” given the average size of an entree in that city.)

Almost as if she can hear Kiesling breathing down her neck, Bunny tries to justify her choices, parroting her bossʻs pro-oil arguments in her conversations with her brother’s environmentalist girlfriend. When she loses the argument, she goes for a swim and reposes in the comfort of her industry expertise, “thinking rebelliously about soft salt domes and ancient stones and flat-bottomed barges transported in pieces across the earth.”

As it follows Bunny through the garden of forking paths, the narrative asks us to reflect on all the unintended consequences of mere existence. Like all of us, Bunny comes into contact throughout her life with any number of random people, from petty colleagues in the engineering firmʻs admin pool to one-night stands at the wedding of a childhood friend. Neither she nor the reader can ever know what effect she has on the course of those people’s lives. In just the same way, she can’t recognize her own role in the destruction of the earth — can’t see that after sowing the wind at her women in energy conferences she will someday reap the whirlwind in the form of heat waves and hurricanes. Even someone like this, the book seems to say, has a fearful agency. When describing Bunny’s mother’s new vegetable garden, the narrator notes that “it had taken very little time, in the scheme of things, to totally remake the earth.”

Or maybe not. Toward the end, after a climactic return to Baku and an encounter with an old flame, the timeline starts to move faster, and the external world pushes in to drown out Bunny’s internal monologue. The narrative becomes a haze of headlines about oil and gas mergers, presidential elections, pandemics, and climate disasters. Is this a sign that Bunny’s habitual ignorance is at last giving way to a more defined political consciousness? Or is the narrative pulling away from its head-in-the-sand protagonist, reminding us that the story of the earthʻs collapse is much bigger than mere human emotions?

The novel’s final feint raises a deep set of questions about how to depict climate change in fiction. After first posing as a novel of slow and delayed self-discovery, Mobility at the end almost seems to adopt the structure of classical tragedy, forcing Bunny to live in the world that her work for old Turnbridge’s oil company helped to create. She “wonders whether she would see her father and brother and sister-in-law again,” Kiesling tells us in the final chapter. “Flying was out of the question for Elizabeth; the turbulence had gotten too bad … they could always drive the van somewhere to get out of the smoke for a while.”

It’s unclear whether the external world is taking revenge on Bunny for her actions, a la Sophocles, or whether Bunny just happens to have been alive during a specific chapter of ecological collapse — in other words, it’s unclear whether we should think about the narrative in human time or in geologic time. For Kiesling to provide an answer to this question would also be for her to pass judgment on Bunny, and she avoids doing so. There’s a lesson in there for many climate-conscious readers in a country that has emitted the largest share of historical carbon. However Bunny’s life may differ from our own, we too are both guilty and not.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Forget eco-activists: This climate novel stars an oil industry shill on Sep 1, 2023.