This holiday season set a sustainable example for the little ones in our lives with…

The post Sustainable Holidays: Gifts for the Kids appeared first on Earth911.

This holiday season set a sustainable example for the little ones in our lives with…

The post Sustainable Holidays: Gifts for the Kids appeared first on Earth911.

When you shop, do you think about how far what you’re buying has to travel?…

The post We Earthlings: The CO2 Cost of Shipping appeared first on Earth911.

Diplomats, academics, and activists from around the globe will gather yet again this week to try to find common ground on a plan for combating climate change. This year’s COP, as the event is known, marks the 28th annual meeting of the conference of the parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. More than 70,000 people are expected to descend on Dubai for the occasion.

In addition to marathon negotiations and heated discussions, the fortnight-long assembly will see all manner of marches, rallies, speakers, advocacy, and lobbying. But, aside from fanfare, it remains unclear how much COP28 will, or can, achieve. While there have been signs that the United States and China could deepen their decarbonization commitments, countries have struggled to decide how to compensate developing countries for climate-related losses. Meanwhile, global emissions and temperatures continue climbing at an alarming rate.

That has left some to wonder: Have these annual gatherings outlived their usefulness?

To some, the yearly get-togethers continue to be a critical centerpiece for international climate action, and any tweaks they might need lie mostly around the edges. “They aren’t perfect,” said Tom Evans, a policy analyst for the nonprofit climate change think tank E3G. “[But] they are still important and useful.” While he sees room for improvements — such as greater continuity between COP summits and ensuring ministerial meetings are more substantive — he supports the overall format. “We need to try and find a way to kind of invigorate and revitalize without distracting from the negotiations, which are key.”

Others say the summits no longer sufficiently meet the moment. “The job in hand has changed over the years,” said Rachel Kyte, a climate diplomacy expert and dean emerita of the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University. She is among those who believe the annual COP needs to evolve. “Form should follow function,” she said. “And we are using an old form.”

Durwood Zaelke, co-founder and former president of the Center for International Environmental Law, was more blunt. “You can’t say that an agreement that lets a problem grow into an emergency is doing a good job,” he said. “It’s not.”

Established in 1992, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change is an international treaty that aims to stabilize greenhouse gas emissions and avoid the worst effects of climate change. Some 198 countries have ratified the Convention, which has seen some significant wins.

The 1997 Kyoto Protocol marked the first major breakthrough, and helped propel international action toward reducing emissions — though only some of the commitments are binding, and the United States is notably absent from the list signatories. The 2015 Paris Agreement laid out an even more robust roadmap for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, with a target of holding global temperature rise to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above preindustrial levels, and “pursuing efforts” to limit the increase to 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F).

Although the path to that future is narrowing, it is still within reach, according to the International Energy Agency. But, some experts say, relying primarily on once-a-year COP meetings to get there may no longer be the best approach.

“Multilateral engagement is not the issue anymore,” Christiana Figueres said at a conference earlier this year. She was the executive secretary of the Convention when the Paris agreement was reached, and said that while important issues that need to be ironed out on the international level — especially for developing countries — the hardest work must now be done domestically.

“We have to redesign the COPs…. Multilateral attention, frankly, is distracting governments from doing their homework at home,” she said. At another conference a month later, she added, “Honestly, I would prefer 90,000 people stay at home and do their job.”

Kyte agrees and thinks it’s time to take at least a step back from festival-like gatherings and toward more focused, year-round, work on the crisis at hand. “The UN has to find a way to break us into working groups to get things done,” she said. “And then work us back together into less of a jamboree and more of a somber working event.”

The list of potential topics for working groups to tackle is long, from ensuring a just transition to reigning in the use of coal. But one area that Zaelke points to as a possible exemplar for a sectoral approach is reducing emissions of methane, a greenhouse gas with more than 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide in the first 20 years after it reaches the atmosphere.

“Methane is the blow torch that’s pushing us from global warming to global boiling,” he said. “It’s the single biggest and fastest way to turn down the heat.”

To tackle the methane problem, Zaelke points to another international agreement as a model: the Montreal Protocol. Adopted in 1987, that treaty was aimed at regulating chemicals that deplete the atmosphere’s ozone layer, and it has been a resounding success. The pollutants have been almost completely phased out and the ozone layer is on track to recover by the middle of the century. The compact was expanded in 2016 to include another class of chemicals, hydrochlorofluorocarbons.

“It’s an under-appreciated treaty, and it’s an under-appreciated model,” said Zaelke, noting that it included legally binding measures that the Paris agreement does not. “You could easily come to the conclusion we need another sectoral agreement for methane.”

Zaelke could see this tactic applying to other sectors as well, such as shipping and agriculture. Some advocates — including at least eight governments and the World Health Organisation — have also called for a “Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty”, said Harjeet Singh, the global engagement director for the initiative. Like Zaelke, Kyte, and others, he envisions such sectoral pushes as running complementary to the main Convention process — a framework that, while flawed, he believes can continue to play an important role.

“The amount of time we spend negotiating each and every paragraph, line, comma, semicolon is just unimaginable and a colossal waste of time,” he said of the annual events. But he adds the forum is still crucial, in part because every country enjoys an equal amount of voting power, no matter its size or clout.

“I don’t see any other space which is as powerful as this to deliver climate justice,” he said. “We need more tools and more processes, but we cannot lose the space.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Why some experts say COPs are ‘distracting’ and need fixing on Nov 28, 2023.

This story was originally published by Inside Climate News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

At the tail end of the aughts, as it became clear that the United States would need to create much more renewable energy, fast, many believed the transition would be bolstered by the proliferation of offshore wind. But not off the coasts of states like Massachusetts and California, where it’s best positioned today. They thought the industry would emerge, and then take hold, in the Great Lakes.

Things looked promising for a while. Glimmers of an offshore wind boom arose from the depths of the Great Recession, as developers offered up proposals on both the U.S. and Canadian sides of the lakes. In 2010, the Cleveland-based Lake Erie Energy Development Corporation, better known as LEEDCo, announced plans to install its first 20 megawatts by 2012 and scale up to 1,000 megawatts by 2020. Two years later, the Obama administration and five states—though not Ohio—formed the Great Lakes Offshore Wind Consortium to help streamline the permitting process.

“That was really a peak of burgeoning interest in climate,” said Greg Nemet, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who studies energy policy. “There was also a spike in energy prices just before the global financial crisis … that also stimulated awareness and interest in energy. And at the same time, the prices of renewable energy were really starting to come down.”

The wind that blows over the Great Lakes is stronger and more consistent than what inland wind farms receive. It holds steady even in the middle of the day, when power demand is high but generation from onshore wind farms tends to slow down. Which means that, in theory, tapping into the wind resource over the lakes would allow the electric grid to rely more on renewables without being as affected by their intermittency.

Yet more than a decade on, none of those early offshore wind projects have succeeded. There are still no commercial wind turbines in any of the five Great Lakes. And as the industry debates when, if ever, it will give the region another shot, those who tried before want newcomers to avoid making the same mistakes that they did.

Perhaps the most famous (or most infamous) such proposal is Icebreaker Wind, the sole project of Cleveland’s LEEDCo, a public-private nonprofit launched by several lakefront counties and a local foundation in 2009. By most accounts, the six-turbine pilot project is the most successful Great Lakes offshore wind initiative of its time—even though it may never be built.

“They were really ahead of their time,” Nemet said of LEEDCo. “It’s high risk, and just because it’s high risk doesn’t mean it’s a bad idea…You can learn from success, but you can also learn from failure.”

Two key qualities set Icebreaker apart from nearly all of its counterparts: It has been permitted, and it hasn’t been canceled. It survived the labyrinth of federal reviews and state and local hearings that took out the handful of others that made it that far. And it’s being spearheaded by a developer that, despite blow after blow from local policymakers, still hasn’t given up.

These days, though, LEEDCo is struggling to overcome the resistance it’s faced from birders, anti-wind groups and fossil fuel interests.

“There was an awful lot of delay and uncertainty,” said Will Friedman, president and CEO of the Cleveland-Cuyahoga County Port Authority and the acting president of LEEDCo. (The nonprofit, which no longer has any full-time staff, is being held together by Friedman and a few other volunteers.)

Following years of permitting slowdowns, LEEDCo sparred with Ohio regulators in 2020 over conditions tacked onto a key state permit that it said would’ve killed the project, then slogged through an Ohio Supreme Court case—brought by area residents but partly funded by a coal company—that lasted another year and a half. It won both, but development has dragged on for so long now that some of LEEDCo’s initial work has become outdated.

“While we currently hold all the permits, we don’t know if we can build the project consistent with the original permits, so maybe we have to go back to the drawing board and do that over again,” Friedman said. With a resigned chuckle, he added, “Do we then open ourselves up to being sued again by opponents?”

The challenges LEEDCo has confronted are far from unique. Onshore renewable energy projects have long faced pushback from prospective neighbors and are, increasingly, being met with inhospitable new regulations designed to shut them down. The idea of offshore wind turbines being built within sight of beloved coastlines can have entire communities up in arms.

“I think a lot of policymakers are hesitant to get offshore wind attached to their name, because it’s such a controversial technology,” said Doug Bessette, an associate professor at Michigan State University whose work explores the acceptance of renewables. “I think people are afraid to push it forward.”

Most of the Great Lakes region has made little headway on enacting policies that would help offshore wind. Efforts to change state or Canadian provincial laws to facilitate or subsidize offshore wind projects have struggled to gain momentum. For pilot-sized wind farms like Icebreaker, designed to prove that the technology is safe and effective, but too small to take advantage of economies of scale, cost remains a nearly insurmountable barrier.

The progress made by offshore wind projects in the Northeast, where supportive policies have found more traction and turbines have actually made it into the water, could be a boon for the industry if it ever returns to the Great Lakes, according to David Bidwell, an associate professor in the University of Rhode Island’s Department of Marine Affairs.

There’s real data now on offshore wind farms’ socioeconomic impacts, along with evidence that overwhelming public opposition is not, in fact, inevitable. While the approval process would be different—Great Lakes states have more authority over the lakebed than East Coast states have over the ocean floor—and studies on things like bird migration routes wouldn’t translate very well, the region would no longer be starting from scratch.

But there are also infrastructure barriers specific to the Great Lakes, Bessette noted. U.S. supply chains for freshwater turbines, designed to resist annual icing and de-icing, don’t exist. The workforce hasn’t been trained. There are a limited number of ports deep enough to support offshore wind, and some of those don’t yet have the capacity. There’s no way to get a ship big enough to put up turbines through the St. Lawrence River and into the lakes, meaning that the first company to make it to the construction phase will probably need to build one.

Offshore wind turbines themselves have advanced considerably in the last decade and a half, thanks to ongoing research and their continued deployment in Europe and, more recently, on the U.S. East Coast. They’re sturdier. More efficient. Better at withstanding freshwater ice. All that technological progress will inevitably boost the odds of an offshore wind project one day succeeding in the Great Lakes.

The political climate may be working against them, however. In the early 2010s, and maybe even more recently than that, there was an appetite in the Great Lakes region for bold new clean energy projects, Bessette said. “I don’t know if we’re there right now.”

Still, as the developers that flocked to the Great Lakes region back then quickly learned, building wind turbines that are visible from shore has never been an easy sell, even in places that are supportive of the idea of creating more renewable energy.

In many ways, the Great Lakes offshore wind sort-of-boom started in Canada. Toronto-based Trillium Power led the charge. The company’s plan was ambitious: 80 turbines, situated on a shallow shelf about 10 miles off Ontario’s mainland, together capable of generating roughly 500 megawatts of electricity.

The concept went over well at first, according to John Kourtoff, Trillium’s CEO. Kourtoff felt like local officials were on his side until a swarm of other developers—over a half-dozen by some counts—got the same idea. Some of the projects, he said, were proposed very close to shore, well within the lake views of affluent communities. That’s what he believes turned the tide of public opinion.

Trillium almost made it to construction. “We were just ready to close the financing to do detailed engineering for two specialized barges that we were having made to erect the turbines,” Kourtoff said.

It was Feb. 11, 2011, a Friday, when he got the call. Facing increasing public opposition to offshore wind months, and with a general election coming up that October, Ontario had imposed a moratorium on offshore wind. Ontario officials cited a lack of scientific research on the turbines’ impacts. Offshore wind’s proponents believe, however, that the moratorium was prompted by opposition from the public and from the province’s influential nuclear power industry.

Following the cancellation, Trillium sued, ultimately securing a partial victory in response to its claim that the province had destroyed relevant evidence, but failing to convince the courts of its primary argument that officials had targeted the project unfairly when they issued the moratorium.

Twelve years later, Kourtoff hasn’t given up on his flagship offshore wind project, or on the three others he wants to build in the Great Lakes. But he hasn’t been able to move forward on any of them, either. The moratorium is still in place.

Toronto Hydro, the city-owned electric utility, relinquished its own vision for offshore wind after the province’s moratorium went into effect. It had planned to start with an approximately 20-turbine, 100-megawatt project at a promising site about two miles offshore, said Joyce McLean, who worked as Toronto Hydro’s director of strategic issues and oversaw its clean energy programs at the time.

“We basically put the anemometer in the lakes, collected the data, and then there was nothing for us to do, because the program disappeared,” McLean said. The province, she said, “couched [the moratorium] in terms of ‘Well, we’re going to study it.’ But they never did, and it was deemed dead.”

Residents had reacted more strongly to the proposal than the utility expected. They’d packed its public meetings to ask about what would happen to their views and their property values and whether construction would stir up old industrial toxins sitting on the lakebed. One man, McLean said, yelled in her face about the harm the project would cause him. Then the moratorium came down, and the wind project went away.

“I think that we were a cautionary tale,” McLean said.

Scandia Wind arrived in Grand Haven, Michigan, even less prepared for the backlash it would face. The prospect of somewhere between 100 to 200 turbines, some of them situated as close as a mile and a half to shore, didn’t sit well with the beachfront city. The Norwegian developer’s later decision to reduce the scale of the project by half and move it six miles offshore did little to remedy the situation. In the end, unable to win over much of the community, Scandia was all but run out of town.

“I think they came with a mindset that, ‘Well, we have crossed these thresholds in Europe, and surely the Americans, with their desire for renewable energy, would welcome similar developments in their Great Lakes,’” said Arnold Boezaart, then-director of Grand Valley State University’s Michigan Alternative and Renewable Energy Center. “Well, they miscalculated.”

Some Michigan leaders believe that the fallout from Scandia ruined the chances for any offshore wind project to move forward in the area. Boezaart disagrees. “Even without Scandia,” he said, the offshore wind industry would still be figuring out how to better navigate public concerns about safety and visibility. “But certainly, there’s no question that Scandia Wind caused a big dustup during that time.”

In 2009, the New York Power Authority put out its own call for offshore wind projects aimed at a swath of eligible sites in Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. Several interested developers responded, but facing higher-than-expected costs and angrier-than-expected residents, the state-owned power organization scrapped the idea in 2011.

The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority revisited the question of Great Lakes offshore wind two years ago. Advocates hoped the results of its feasibility study, published in December 2022, would catalyze new development across the Great Lakes region. Instead, NYSERDA found that freshwater offshore wind “currently does not offer a unique, critical, or cost-effective contribution” toward the state’s climate goals, and concluded that “now is not the right time to prioritize Great Lakes Wind projects in Lake Erie or Lake Ontario.”

Walt Musial, a principal engineer and offshore wind researcher at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory who worked on the New York state feasibility study, isn’t sure turbines that are anchored to the ground will ever succeed, at least at scale, in the Great Lakes. He anticipates, though, that floating turbines will be a game-changer, tapping into some of the lakes’ best winds and potentially opening the door to the sort of growth that LEEDCo envisioned in the early 2010s.

“In Lake Michigan, for example, you can go 15, 20 miles out, get out of the viewshed of most people,” Musial said. “You can avoid the ice, you can avoid the birds and you can avoid the toxic sediments that people are concerned [about]. … So maybe we made a mistake not looking at that sooner, but I think that’s where the biggest opportunities will be in the Great Lakes.”

Floating wind turbines are still being tested. Floating freshwater wind turbines are even more experimental. But Musial is one of many offshore wind researchers who suspect that when the technology does mature, it’ll unleash a plentiful new source of relatively dependable renewable electricity—assuming, as many do, that the grid will still need it by then.

Yet none of offshore wind’s lingering limitations have dissuaded more than 50 Illinois state lawmakers from pushing for a 150-megawatt (or larger) pilot project to be built somewhere along the state’s coast. Ideally, they want it near the Southeast side of Chicago, where the low-carbon electricity the wind farm would generate and the local economic boost it would provide are both very much needed.

The Illinois Rust Belt to Green Belt Program Act would authorize surcharges on ratepayers’ bills once the pilot project goes into operation—guaranteeing it the sort of state-backed financial support that no Great Lakes offshore wind project has ever received (and which Icebreaker’s advocates, despite years of lobbying, couldn’t convince the Ohio General Assembly to provide). A Lake Michigan pilot, if built, would also supply the sort of unparalleled efficacy and impact data that the offshore wind industry has long hoped would come from Icebreaker.

The bill fell short in 2022 and again in 2023. Its backers plan to keep trying.

“Let’s get going,” said state Rep. Marcus Evans Jr., one of the bill’s sponsors. “What are we waiting for? I don’t want to be 185 years old when these things come to fruition. So we need a policy to make it happen. We need action. Things don’t just happen. You have to do something.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline What happened to the Great Lakes offshore wind boom? on Nov 28, 2023.

The largest iceberg in the world — A23a, nearly 1,500 square miles, about three times as big as New York City — has broken free of its anchor on the floor of the Weddell Sea and begun to drift toward the Southern Ocean.

In 1986, the Antarctic iceberg calved off the Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf in the western part of the continent, quickly becoming stuck on the seafloor, reported Reuters.

According to Dr. Andrew Fleming, a British Antarctic Survey (BAS) remote sensing expert, it was only a matter of time before the colossal chunk of ice broke loose.

“I asked a couple of colleagues about this, wondering if there was any possible change in shelf water temperatures that might have provoked it, but the consensus is the time had just come,” Fleming said, as the BBC reported. “It was grounded since 1986 but eventually it was going to decrease (in size) sufficiently to lose grip and start moving. I spotted first movement back in 2020.”

At the time of its calving, A23a was home to a Soviet research station.

The iceberg, which weighs about a trillion tons and is also one of the planet’s oldest, has recently begun moving more quickly with the aid of currents and winds and is drifting past the Antarctic Peninsula’s northern tip.

Oliver Marsh, a glaciologist with BAS, said seeing such a giant iceberg actually moving is a rarity, reported Reuters.

“Over time it’s probably just thinned slightly and got that little bit of extra buoyancy that’s allowed it to lift off the ocean floor and get pushed by ocean currents,” Marsh said, as Reuters reported.

The huge berg will most likely become swept up by the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, which will push it in the direction of the Southern Ocean and “iceberg alley,” where other icebergs float.

In 1916, the Anglo-Irish explorer Ernest Shackleton used the current in his harrowing Antarctic escape after his ship Endurance became trapped, broke up and sank in the Weddell Sea the previous year, reported CBS News. The sunken shipwreck was discovered in 2022.

Another possible outcome for A23a is for it to run aground at South Georgia Island, which would threaten the millions of penguins, seabirds and seals that breed on the Antarctic island and follow established foraging routes in its surrounding waters.

A separate iceberg, A68, looked as though it might crash into South Georgia Island in 2020, but ended up breaking apart, which could also happen to A23a.

However, Marsh explained, “an iceberg of this scale has the potential to survive for quite a long time in the Southern Ocean, even though it’s much warmer, and it could make its way farther north up toward South Africa where it can disrupt shipping,” as Reuters reported.

However, these enormous shards of ice are not just dangerous beauties floating through remote, chilly waters. They serve an important purpose in the larger ecosystem by releasing minerals as they melt, reported the BBC. The dust that collected in their ice as they scraped along Antarctica’s rock bed serves as a nutrient source for tiny organisms at the base of marine food chains.

“In many ways these icebergs are life-giving; they are the origin point for a lot of biological activity,” said Dr. Catherine Walker, a scientist with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, as the BBC reported.

The post World’s Largest Iceberg Breaks Free in Antarctica appeared first on EcoWatch.

According to a White House official, U.S. President Joe Biden will not be attending the United Nations COP28 Climate Conference, which begins this Thursday in Dubai.

The meeting of world leaders and delegates — including climate scientists, Indigenous Peoples and youth — to discuss the climate crisis has been held annually at various international locations since 1995.

Last month, Reuters reported that the president was not likely to attend the meeting due to presidential campaign commitments and demands related to the war in the Middle East.

“They’ve got the war in the Middle East and a war in Ukraine, a bunch of things going on,” said John Kerry, U.S. special envoy for climate change, last week, as The New York Times reported. Kerry will attend the conference in Dubai, along with his team.

Leaders from almost 200 countries, including Pope Francis, King Charles III, who will give the opening address, and UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, are expected to be present at the conference.

Biden has attended the annual conference for the past two years, and referred to climate change as “the ultimate threat to humanity” earlier this month.

President of China Xi Jinping is also planning to skip the conference, reported Bloomberg.

The world leaders’ summit at COP28 will be held on Friday and Saturday, December 1 and 2.

According to the White House, the president’s schedule for this week includes a meeting with President of Angola João Manuel Gonçalves Lourenço, which is set to include a discussion on energy and climate, and the National Christmas Tree lighting on Thursday, Axios reported. President Biden is also set to attend a reception for honorees of the Kennedy Center on Sunday.

Biden’s decision not to attend the important climate conference is likely to upset climate activists.

According to analysts, it is not protocol for a president of the U.S. to be in attendance at every climate summit, reported The New York Times.

“I don’t quite see why you send a president to an event that doesn’t have a marquee outcome,” said David Victor, a Brookings Institution nonresident senior fellow, adding that President Biden’s absence sends “a message that there’s not much to be done by sending a leader,” as The New York Times reported.

The slow progress of nations on scaling back the use of fossil fuels and limiting global heating to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels is expected to be discussed in Dubai.

The planet has already reached an average of 1.2 degrees Celsius of warming.

According to scientists, by 2030 emissions must be reduced by 43 percent lower than 2019 levels in order to avoid disastrous climate impacts. However, current U.S. climate goals will only result in a reduction of seven percent.

Unless the world keeps warming below this threshold, scientists say humans will struggle to adapt to global changes such as heat waves, drought, wildfires and extreme weather.

The post Biden to Skip COP28 Climate Conference appeared first on EcoWatch.

The Western gray squirrel (Sciurus griseus) has been listed as a threatened species in the state of Washington since 1993. Now, the state has decided to list the species, sometimes known as the silver gray squirrel, as endangered.

Following a periodic status review meeting on Nov. 17, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) requested an approval from the department’s Commission to reclassify the Western gray squirrel as endangered.

According to the WDFW presentation during the review meeting, the species had a declining population in the late 1800s, and it became rare to see these squirrels by the 1970s. Today, their range has declined further, leaving just three isolated populations in the state. The remaining populations are located in Okanogan County, Klickitat County and Joint Base Lewis-McChord.

While the total number of squirrels is unknown, WDFW estimated about 400 to 1,400 remaining squirrels in the state, Oregon Public Broadcasting reported.

Despite recovery efforts, the number of Western gray squirrels has continued declining. WDFW explained that worsening wildfires linked to climate change could be to blame, noting that since the squirrels were first listed as threatened, their habitat in the Cascade Mountain Range has decreased more than 20%. Logging and development have also contributed to the habitat loss, and disease contributed to significant losses of Western gray squirrels in the population around Klickitat County in the late 1990s through 2005.

“These shy forest squirrels need better protection for their habitat from logging and other threats,” Noah Greenwald, endangered species program director at the Center for Biological Diversity, said in a statement. “I’m hopeful that endangered status will ring the alarm bells and spur action.”

The Western gray squirrel, which features a long and bushy tail and is often confused with the non-native Eastern gray squirrel, is the largest native tree squirrel in Washington. The Western gray squirrel prefers habitats with transitional forests of coniferous to deciduous trees. This type of habitat provides the squirrels with the appropriate food and nesting sites they need to thrive.

Although the species will be listed as endangered in Washington, it is not listed under the federal Endangered Species Act. The Western gray squirrel was considered for federal protections in 2003 but was denied in 2004.

With the decision to list the species as endangered, the next step will be to strengthen protections and recovery efforts.

“We’re happy to see that the commission made a unanimous decision to uplist the western gray squirrel,” Rudy Salakory, conservation director at Friends of the Columbia Gorge, shared in a statement. “Now the hard but critical work of developing stronger protective measures begins. We hope to see changes that favor this vanishing species.”

The post Western Gray Squirrel Listed as Endangered in Washington State appeared first on EcoWatch.

Business may be the most potent force in the world, perhaps more powerful than government….

The post Earth911 Podcast: The Rise of the Activist Leader In Business appeared first on Earth911.

Single-use packaging that bedevils nature and our society today was born more than 50 years…

The post Is It Time for a Return to Refillables? appeared first on Earth911.

Just weeks after the deadliest wildfire in modern U.S. history ripped through the coastal town of Lāhainā, Native Hawaiian taro farmers, environmentalists, and other residents of West Maui crowded into a narrow conference room in Honolulu for a state water commission hearing.

The chorus of criticism was emotional and persistent. For nearly 12 hours, scores of people urged commissioners to reinstate an official who had been key to strengthening water regulations and to resist corporate pressure to weaken those regulations. One after another, they calmly and deliberately delivered scathing criticism of a developer named Peter Martin, calling him “the face of evil in Lāhainā” and “public enemy number one.”

One person summed up the mood of the room when he said, “F— Peter Martin.”

More than 100 miles away on Maui, Martin followed parts of the hearing through a livestream on YouTube. Despite the deluge of criticism, he wasn’t upset. He wasn’t even surprised. After nearly 50 years as a developer on Maui, he’s used to public criticism.

“When you’re around a gang of people, a mob, the commissioners just listen to the mob, they don’t listen to reasoned voices,” Martin told Grist. “I’m not comparing these people to Hitler; I’m just saying Hitler got people involved by hating, hating the Jews.”

Martin, who is 76, has long been controversial. He moved to Maui from California in 1971 and got his start picking pineapples, teaching high school math, and waiting tables. Before long, he began investing in real estate. His timing was perfect: Hawaiʻi had become a state just 12 years earlier, and Maui’s housing market was booming as Americans from the mainland flocked there. By 1978, local headlines were bemoaning the high price of housing, and prices only went up from there.

Developer Peter Martin told the New Yorker that protecting water for Native Hawaiian cultural practices was “a crock of shit,” and that invasive grasses and “this stupid climate change thing” had “nothing to do with the fire.”

Martin points to a map of West Maui, indicating an area where he hopes to build homes. Next to him is his Bible, which he often quotes in conversations and emails. Cory Lum / Grist

Over the last five decades, Martin has made millions of dollars off this real estate boom, building a development empire on West Maui and turning hundreds of acres of plantation land into a paradise of palatial homes and swimming pools. He owns or holds interest in nearly three dozen companies that touch almost every aspect of the homebuilding process: companies that buy vacant land, companies that submit development plans to local governments, companies that build houses, and companies that sell water to residents. His real estate brokerage helps find buyers for homes built on his land, and he’s even got a company that builds swimming pools.

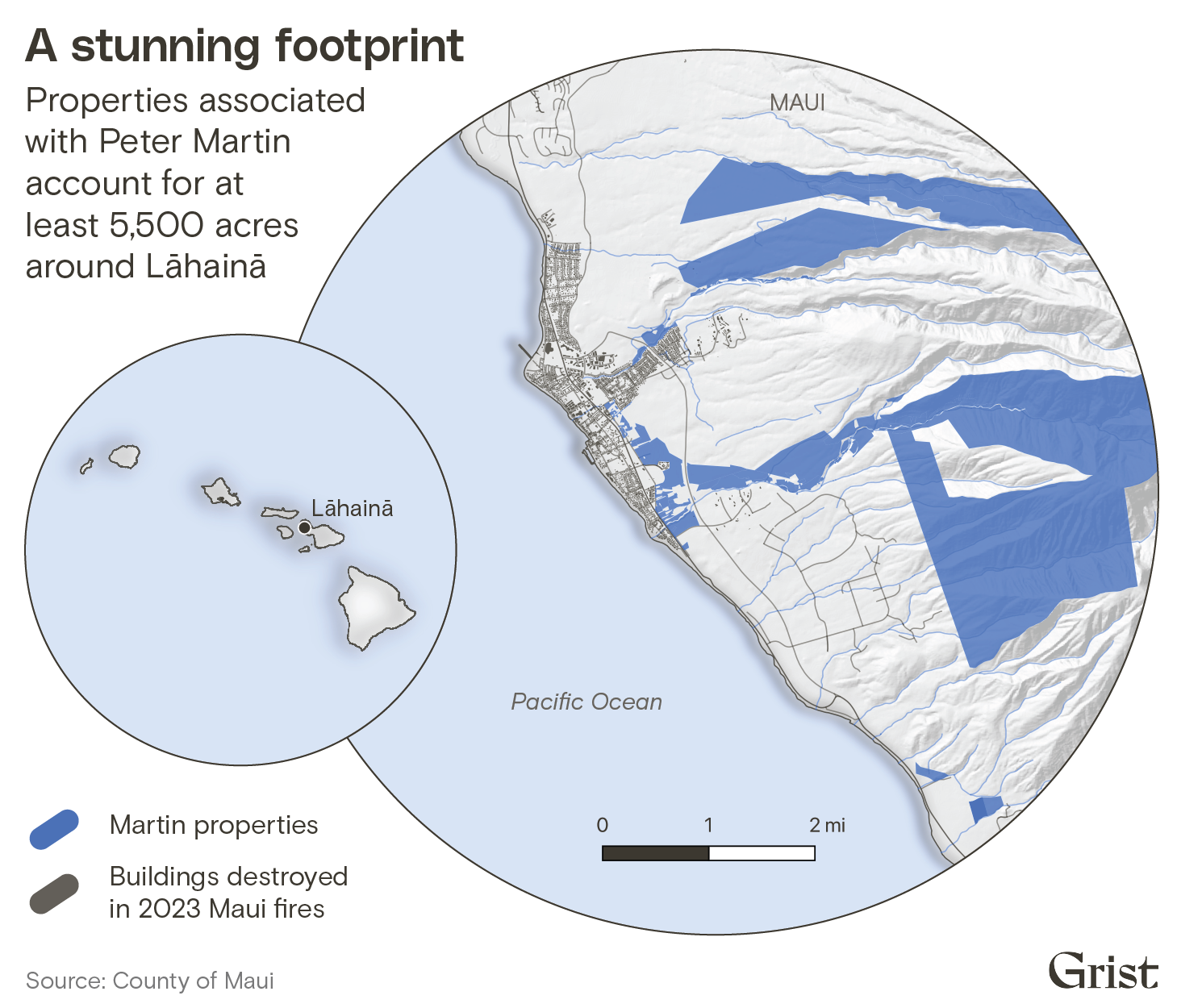

Companies associated with Martin own more than 5,500 acres of land around Lāhainā, according to an analysis of county records, making him one of the area’s largest private landowners, and his web of businesses wields immense influence in West Maui, which is home to about 25,000 people. He drives his white Ford F-150 around the island with a large, black Bible on the center dashboard and peppers his conversations and emails with quotes from Scripture or libertarian economist Milton Friedman. He once served on the Maui County salary commission, where he helped determine pay for elected officials and county department heads, and he has donated $1.3 million to the Grassroot Institute of Hawaii, a libertarian think tank that has fought Native Hawaiian sovereignty. So extensive is the reach of his land empire that the command center for the response to the August wildfires is located on land owned by a company in which he has a stake.

Development on Maui, where the median home price now exceeds $1 million, often sparks controversy, and Martin is far from the only builder who has inspired opposition. But his staunch ideological commitment to free market capitalism and Christianity, coupled with his companies’ persistent pushback against water regulations intended to protect Native Hawaiian rights, has evoked particularly passionate distaste among many locals. “F— the Peter Martin types,” reads one bumper sticker spotted in Lāhainā.

And that was before the wildfire. Just two days after the outbreak of a blaze that would go on to kill 100 people, fueled in part by invasive grasses on Martin’s vacant land, an executive at one of Martin’s companies sent a letter to the state water commission. Glenn Tremble, who works for West Maui Land Company, wrote that the company’s request to fill its reservoirs on the day of the fire had been delayed by the state. He also asked the commission to loosen water regulations during the fire recovery.

“We anxiously awaited the morning knowing that we could have made more water available to [the Maui Fire Department] if our request had been immediately approved,” he wrote.

Tremble’s letter implied that a state official key to implementing local water regulations — and the first Native Hawaiian to lead the state water commission — had impeded firefighting efforts. He soon walked back the claim, but his first letter had immediate effect. The state attorney general launched an investigation into the official, the governor suspended water regulations, and the official was temporarily reassigned. Critics saw it as an attempt to capitalize on the grief of the community for profit.

It didn’t help that within weeks, when the Washington Post asked about the role the invasive grasses on Martin’s land played in the deadly wildfire, Martin said he believed the fire was the result of God’s anger over the state water restrictions.

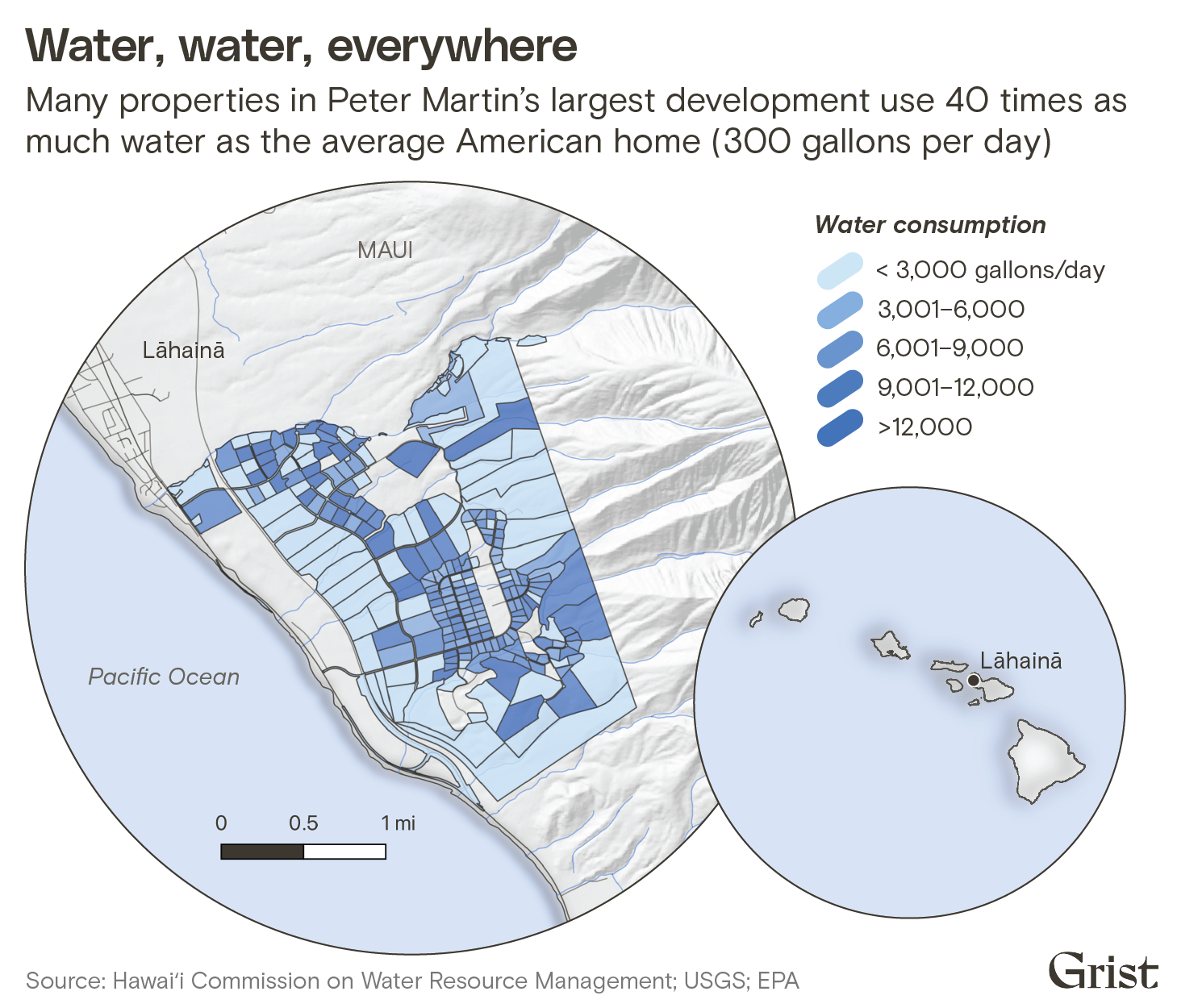

Most people in West Maui get water from the county’s public water system. But Martin-built developments such as Launiupoko, a community of a few hundred large homes outside of Lāhainā, draw their water from three private utility systems that he controls, siphoning underground aquifers and mountain streams to fill swimming pools and irrigate lawns. More than half of all water used in the Launiupoko subdivision, or around 1.5 million gallons a day, goes toward cosmetic landscaping on lawns, according to state estimates. Just over a quarter is used for drinking and cooking.

The scale of this water usage is stunning: According to state data, Launiupoko Irrigation Company and Launiupoko Water Company deliver a combined average of 5,750 gallons of water daily to each residential customer in Launiupoko, or almost 20 times as much as the average American home. The development has just a few hundred residents, but it uses almost half as much water as the public water system in Lāhainā, which serves 18,000 customers.

Martin says he didn’t set out to make Launiupoko a luxury development, but that its value spiked after Maui County imposed rules that limited large-scale residential development on agricultural land. Martin’s development was grandfathered in under those restrictions, and demand for large homes drove up prices in the area. He says criticism of swimming pools and landscaped driveways is rooted in envy.

“People come over and make their land beautiful by using water,” he said.

Martin also maintains that there’s more than enough water for everyone, but that doesn’t seem to be the case. Annual precipitation around Lāhainā declined by about 10 percent between 1990 and 2009, drying out the streams near Launiupoko, and now Martin sometimes can’t provide water to all his customers during dry periods. The underground aquifer in the area is also oversubscribed, according to state data, with Martin’s companies and other users pumping out 10 percent more groundwater than flows in each year on average. Climate change could exacerbate this shortage by worsening droughts along Maui’s coast: Projections from 2014 show that annual rainfall could decline by around 15 percent over the coming century under even a moderate scenario for global warming.

In response, the state water commission has intervened to stop Martin and other developers from overtapping West Maui’s water, setting strict limits on water diversion and fining his companies for violating those rules. Last year, the state took full control of the region’s water, potentially jeopardizing the future of Martin’s luxury subdivisions and making it harder for him to build more in the area.

Now, though, Martin is poised to play a key role as West Maui recovers from the Lāhainā wildfire, which destroyed 2,200 structures, including six housing units Martin had developed. Nine of his employees lost their homes. As of early November, more than 6,800 displaced people on Maui remained in hotels or other temporary lodging. Millions of dollars in federal funds are expected to flow into the state for reconstruction. Martin, with his dozens of development companies and thousands of acres of vacant land, is perfectly positioned to build new homes. And his concerns about water regulations slowing development may find a more sympathetic audience as local officials seek to address a post-fire housing crisis.

Moreover, he is itching to build. Before the fire, county and state officials were shooting down most of his new building proposals amid a concern about overdevelopment, even the ones that Martin pitched as affordable workforce housing. Martin thinks he can mitigate West Maui’s fire risk and its housing crisis by getting rid of the barriers that prevent developers like himself from building more houses with irrigated farms and green lawns.

“What I just want is the water to be able to be used on the land, which God intended it to,” he said.

Daniel Kuʻuleialoha Palakiko doesn’t know what deity Martin is referring to.

“Ke Akua is a God of love and restoration and abundant life,” he told the water commission during September’s hearing, using the Hawaiian word for God. Palakiko had flown to Honolulu with many other Maui residents to urge the state officials to uphold their responsibility to protect water.

Palakiko doesn’t take his land, or water, for granted. He was a teenager in Lāhainā in the 1980s when his family started getting priced out by rising rents. That’s when his dad remembered that his own father had once shown him the family’s ancestral land in nearby Kauʻula Valley. According to Palakiko’s grandfather, the family had been forced out by the Pioneer Mill sugar plantation, which had diverted the Palakikos’ water to irrigate crops. Palakiko’s family still owned the title to the land, and his father was determined to find a way to reclaim it.

First they cleared brush by cutting firebreaks and burning the overgrowth, controlling the flames with five-gallon buckets of water hauled from a nearby river. Once they had opened enough land to build a house, the Palakikos worked out a deal with Pioneer Mill to restore free water access to their property, connecting their home to the plantation’s water system with a series of 1½-inch plastic pipes.

Access to that water meant that the Palakikos could live on their ancestral land for the first time in generations. Back then, Palakiko says, their property felt isolated from Lāhainā, accessible only by old cane field roads that could take 45 minutes to reach town. But the family didn’t mind. It was enough to be able to stay on Maui when so many other Native Hawaiians were forced by economic necessity to leave.

That isolation didn’t last. In 1999, Pioneer Mill harvested its last sugar crop, ending 138 years of cultivation in Lāhainā. The abandoned fields turned brown and Palakiko heard that the company was selling off thousands of acres. Where once the Palakikos had seen Filipino plantation workers tending to crops, they noticed fair-skinned strangers and surveyors exploring the fallow grounds.

The Palakikos soon realized that the land was now in the hands of Peter Martin, who had joined other local investors to buy everything he could of the old plantation land. These new owners soon subdivided the land and sold parcels at ever higher prices as demand for the area known as Launiupoko kept increasing. It didn’t matter that the area was zoned for agriculture: Like many other developers, Martin took advantage of a legal provision that allowed homeowners to build luxurious estates on such land as long as they did some token farming of crops like fruit or flowers, no matter how perfunctory it might be.

By the time Martin finished the development, which included around 400 homes on around 1,000 acres, he was diverting almost 4 million gallons from the stream every day, according to state data, almost as much as the 4.8 million gallons Pioneer Mill had diverted each day before it shut down.

Some days the Palakiko family would wake up to find no water running through the pipes. By the afternoon, puddles along the stream would evaporate and fish would flop on the hot rocks, suffocating. It wasn’t just the Palakikos who were suffering, but the whole river system: As Martin diverted water from the mountains, the waterway dried up farther downstream, threatening the native fish and shrimp that lived in it. Palakiko appealed to Martin’s new water utility, Launiupoko Irrigation Company, but he said the company was hostile. First it tried to shut off the water the family had been receiving through plastic pipes, then asked the family to pay for water they’d always drawn for free, only relenting after the Palakikos fought back.

In addition to diverting water away from Native Hawaiian families, Martin has tried to force some from their land. In 2002, his Makila Land Company filed a so-called “quiet title” case against the Kapus, another farming family whose land borders the Palakikos, seeking to claim a portion of the family’s ancestral land as its own. This legal strategy, which allows landowners to take control of properties that may have multiple ownership claims, later gained notoriety when Mark Zuckerberg used it to consolidate his holdings on Kauai.

When the Kapus fought back, the company kept them in court for almost two decades, appealing over and over to gain the rights to a 3.4-acre parcel. The situation between Martin and the Kapu family became so tense that in 2020, Martin sought a restraining order against one member of the family, Keeaumoku Kapu, accusing him of “verbally attack[ing] me with an expletive-laced tirade” and blocking Martin’s access to the disputed land. The court imposed a mutual injunction against Martin and Kapu later that year; two years later, Kapu finally prevailed in court and secured the title to his property.

Martin’s companies filed multiple quiet-title lawsuits over the years as Martin sought to consolidate control of the land around Launiupoko. Just after it began litigation against the Kapus, Makila Land Company made a similar claim against a neighboring taro farmer named John Aquino, seeking to seize a portion of the land belonging to Aquino’s family. The company won the slice of land in an appellate court in 2013, but the Aquino family stayed put. Police arrested Aquino in 2020 after two of Martin’s employees drove a semi onto the land; Aquino had smashed the truck’s windows with a baseball bat. Makila later filed a trespassing lawsuit in 2021 against Brandon and Tiara Ueki, who also live near the Kapus. The parties agreed to dismiss the case the following year after an apparent settlement. More recently, Martin has fanned even more frustration by selling properties with contested titles, prompting at least one ongoing legal battle.

Meanwhile, Martin and his fellow investors sought to expand to other parts of West Maui with several large-scale developments in areas along the coastline. In one instance, he and another pair of developers named Bill Frampton and Dave Ward proposed building 1,500 homes, including both single and multifamily housing units, in the small beachfront town of Olowalu, even though water access in the area is minimal and rainfall is declining. The developers later scrapped the project following protests from environmental activists, but in the meantime, Martin sold off a few dozen more lots in Olowalu, where he has a home. He also created another utility, Olowalu Water Company, to supply homes in the area with stream water.

Hawaiʻi, like most of the Western United States, allocates water using a “rights” system: A person or company can own the right to draw from a given water source, often on land they own, but they can’t own the water source itself. In states like Oregon and Arizona, this system has led to conflicts between settlers and tribal nations, but in Hawaiʻi the law provides explicit protection for Native Hawaiian users. State law stipulates that traditional and cultural uses, such as taro farming, “shall not be abridged or denied.” In times of shortage, Native users have the highest priority.

In 2018, the state water commission imposed so-called “flow standards” on several West Maui streams, capping the amount of water that Launiupoko Irrigation Company and Olowalu Water Company could divert at any given time. Palakiko had mixed feelings about this: He didn’t want to cede more control over the water that his family had used for generations, but it felt necessary in order to ensure someone could hold the companies accountable.

Even after these rules took effect, though, Martin’s water utility companies violated them dozens of times. When the state threatened to fine the companies, Launiupoko Irrigation Company stopped taking water from its stream completely. Residents of the lush Launiupoko subdivision soon had to ration irrigation water, and the Palakikos lost their access altogether. Their pipes stayed dry for more than a week until a judge ordered Martin’s company to turn on the tap back on.

As the state cracked down on stream diversions, Martin sought to secure more water by tapping an aquifer beneath Lāhainā. Here again, he was accused of infringing on Native Hawaian cultural resources: When his West Maui Construction Company started digging a ditch for a water line in 2020, it excavated an area that contained Native Hawaiian burial remains, triggering protests. Five Native Hawaiian women activists climbed into the company’s ditch to stop the construction project and were arrested. A judge later found the company broke the law by starting construction on the water line without all the requisite permits.

The new restrictions started to hamper Martin’s development activities. Last year, his Launiupoko Water Company applied to the state’s utility regulator for permission to deliver water to a new area near Lāhainā. The company said it had agreed to supply a nearby landowner with potable water for 11 new homes, and told the state it needed to increase its groundwater pumping by at least 65,000 gallons per day. The regulator rejected the expansion plan, saying the company had omitted “basic information” about where it would get this new water. The landowner that would have received the water was another company in which Martin has an ownership stake.

Even as his companies’ plans faced headwinds, Martin continued to benefit. He loaned Launiupoko Irrigation Company a total of $9 million in recent years as the company tried to expand its Lāhainā well system, charging 8 percent interest. The company tried in 2021 to secure a bank loan for the project, but three banks turned it down, with one noting that the company’s “interest payments to Pete” were “substantial.”

Glenn Tremble, a top executive at West Maui Land Company, the company at the center of Martin’s development empire, said in response to a list of questions that Grist’s statements were “generally false and often libelous.” Tremble noted that Martin has built affordable housing units on West Maui and donated to churches. He said that Martin is “well positioned to assist with recovery and efforts to rebuild.”

If Martin’s track record with water and land made him infamous in Lāhainā, it also invigorated local support for even stricter water controls. Palakiko’s long campaign for more attention to the region’s water problems finally bore fruit last year when the state designated West Maui as a “water management area.” Instead of just setting limits on how much water Martin’s companies could take from West Maui streams at any given time, the state water commission announced that it would revamp the area’s entire water system, giving highest priority to Indigenous cultural uses like taro farming. That may mean limiting access for Martin’s luxury developments, though Tremble disputes this.

“We’ve heard a lot from the community about the development of West Maui Land’s holdings in Launiupoko,” said Dean Uyeno, the interim chair of the state water commission, about the decision. “To continue building in these types of ways is going to keep taxing the resource.” The question, Uyeno said, is whether developers “can … find a way to [be] building more responsible development that balances the resources we have.”

Martin thinks the argument that water is a scarce resource is a “red herring.” He argues that the market is calling for more housing, not more water for native fish that rely on the streams.

“All the people [who] ever come to me say, ‘Peter, can you get me a house? I want a place to live,’” he said. “They don’t go, ‘Oh, I wish I had [shrimp] for dinner.’ That’s not what people tell me. They say, ‘Can’t you give me some house, some land?’ I go, ‘I’d love to but the government won’t let me.’”

In the days before the wildfire, Martin’s executives worked long hours in his West Maui Land Company office filling out 30 state applications justifying their current water usage and seeking more, in accordance with the state’s revamp of the area’s water system. They submitted the applications just days before the state’s August 7 deadline. The day after the deadline, Lāhainā burned.

To Martin, this is not a coincidence. He believes the state water commission’s efforts to more strictly regulate water enabled the fire by preventing more construction of homes with irrigated lawns — in other words, more development would have made West Maui more resilient to fire. The day before the water commissioners met in September, he wondered if the commissioners would acknowledge their responsibility for the wildfire deaths and regretted not pushing harder against their restrictions.

“I feel I actually have blood on my hands because I didn’t fight hard enough,” he said.

There’s no evidence that the state management rules, which are still in the process of going into effect, had any bearing on the fire. When Grist relayed this argument to the interim leader of the state’s water commission, he was stunned.

“That actually leaves me speechless,” said Uyeno. “I don’t know how to respond to that.”

Palakiko and his family spent the day of the fire watching the smoke rising from the coastline, watering the grass on their property and praying the winds wouldn’t shift, sending the flames their way. Five years earlier, another fire fueled by a passing hurricane had burned down two homes on their land.

That day, their prayers were answered. But when Palakiko’s son, a firefighter, came home shaken from his shift fighting the blaze, the family realized that the West Maui they had known their whole lives was gone.

Two days later, Palakiko received another shock when he read Tremble’s letter accusing Kaleo Manuel, the deputy director of the water commission, of delaying the release of firefighting water. The letter argued that Manuel had waited to release water to West Maui Land Company’s reservoir until he had checked with the owners of a downstream taro farm. That farm belongs to the Palakikos.

The company’s allegations were explosive. The state attorney general launched an investigation and requested that the commission reassign Manuel, who had been instrumental in establishing the Lāhainā water management area and was the only Native Hawaiian to ever hold that position. Governor Josh Green temporarily suspended the rules that limit how much water Martin’s companies and other water users can draw from West Maui streams. The state later reinstated Manuel and restored the rules. In a statement to Grist, Tremble said he respects Manuel’s “commitment and his integrity” and said that “the problem is the process, or lack thereof, to provide water to Maui Fire Department and to the community.”

While there was no evidence that filling the reservoir would have stopped the fire from destroying Lāhainā, and firefighting helicopters wouldn’t have been able to access the reservoir due to high winds on the day in question, there’s a growing consensus among scientists in Hawaiʻi that one factor in its rapid spread was the proliferation of nonnative grasses on former plantation lands — including lands that Peter Martin owns.

Before the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893, before the dominance of the sugar industry allowed plantations to divert West Maui’s streams, Hawaiian royalty lived on a sandbar in the midst of a large fishpond within a 14-acre wetland in Lāhainā, which was known as the Venice of the Pacific.

After plantation owners diverted streams for their crops, the royal fishpond became a stagnant marsh, and later was filled with coral rubble and paved over. Now, Palakiko imagines what it would be like if the streams were allowed to resume their original paths: what trees would grow, what native grass could flourish, what fires might be stopped. He doesn’t think this vision is at odds with the need to address Maui’s housing crisis.

For Palakiko, the fight over the future of water in Lāhainā is about more than just who controls the streams in this section of Maui. It’s also in some ways a referendum on what future Hawaiʻi will choose: one that reflects the worldview of people like Palakiko, who see water as a sacred resource to be preserved, or that of people like Martin, who sees it as a tool to be used for profit.

To Martin, such a shift is unsettling.

“I mean, for a hundred years, you could take all the water, and all of a sudden these guys come in, and say, ‘Oh, you can’t take any water,’” Martin said. “And they made it sound like I’m this terrible person.”

This story has been corrected to reflect the updated death toll provided by Maui County.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline The libertarian developer looming over West Maui’s water conflict on Nov 27, 2023.