Brenda Mallory reports directly to President Joe Biden, but in a crowded building at Expo City in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, nobody recognizes her. Mallory is the chair of the Council on Environmental Quality, a White House department in charge of implementing some of Biden’s key climate priorities, and she’s promoting that agenda as the annual United Nations climate conference nears its close.

On Saturday, she’s seated on a couch in the middle of a bustling corridor listening intently to KM Reyes, a community organizer and conservation lobbyist based in the Philippines. With a notepad balanced on her lap, Mallory wants to hear what the U.S. can do to help grassroots advocates like Reyes. “I’m big on details,” she tells her.

“It’s ensuring that we get actual finance on the ground,” Reyes responds. “Because we’re nowhere near the target $20 billion by 2025 in order to fulfill the framework,” she adds, referring to a global biodiversity agreement signed last year.

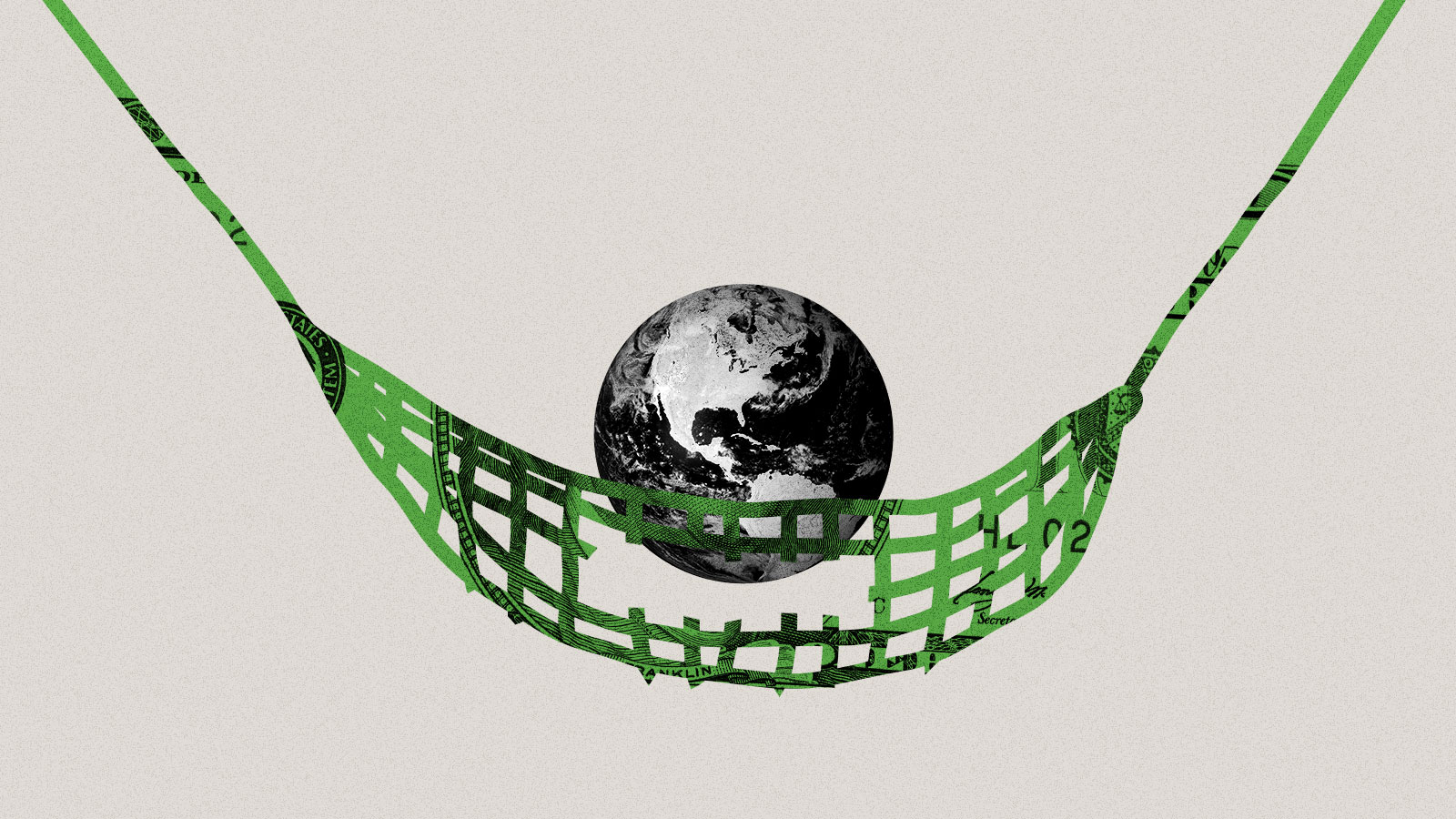

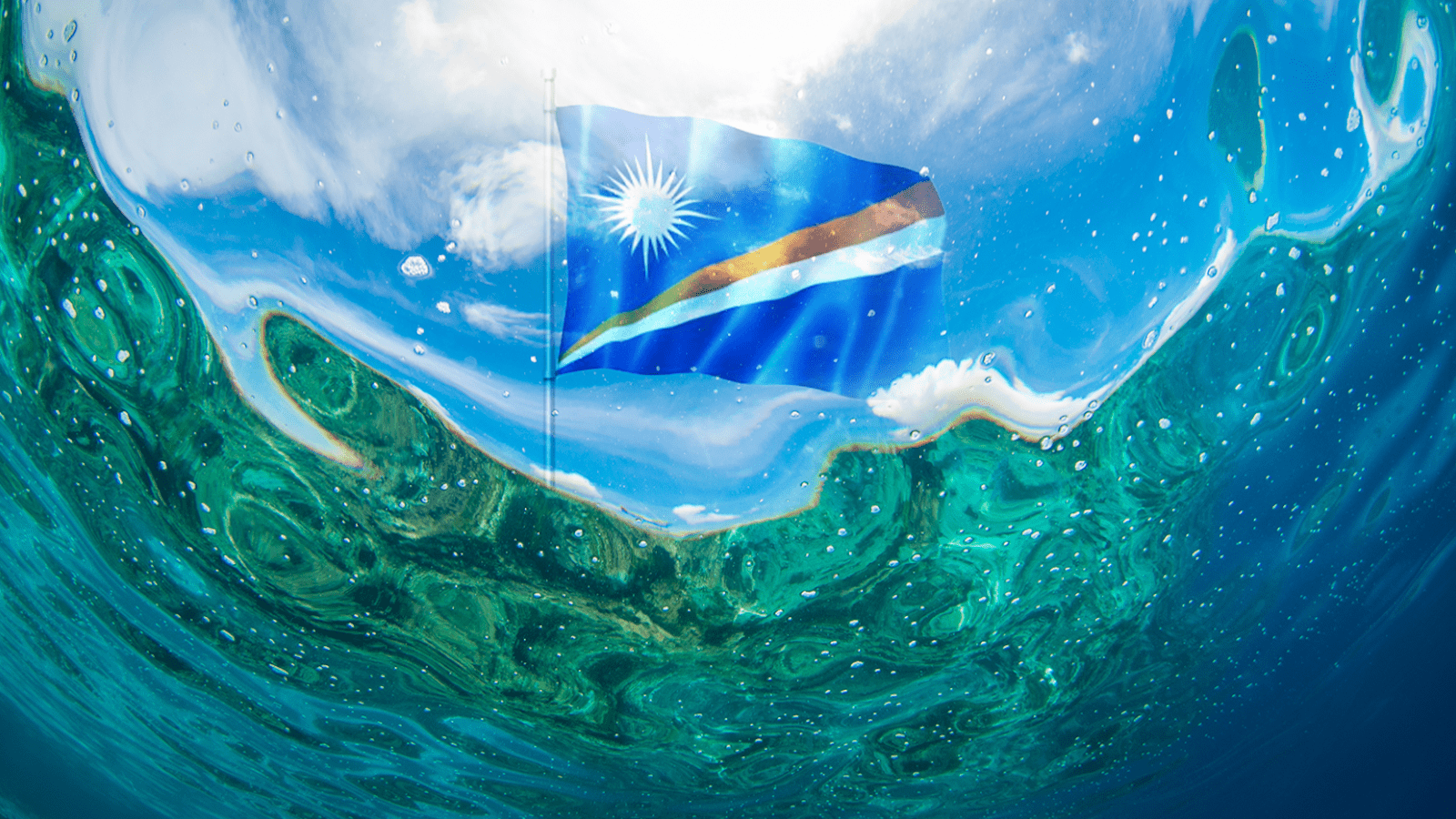

Finance is an overarching concern at COP28, as the conference is abbreviated, and its predecessor gatherings. Global climate and environment agreements recognize that the planet is careening toward disaster largely as a result of carbon pollution by countries that industrialized relatively early in their histories — like the United States — as opposed to those whose economies began developing more recently, like the Philippines.

As a result, developed countries’ commitments to provide financial support to developing countries are at the crux of climate agreements. As the world’s largest historical polluter, the U.S. is expected to provide its fair share to support climate efforts, but it has failed to deliver in recent years. For instance, only $2 billion of the $3 billion that the U.S. pledged to a climate fund in 2014 has been delivered. Nevertheless, a few days prior to Mallory’s arrival in Dubai, Vice President Kamala Harris pledged another $3 billion to the same fund.

But looming over these promises are questions about a divided Congress’ ability to execute U.S. funding commitments, as well as the very real possibility that former president Donald Trump will defeat Biden in an election next year, throwing U.S. climate policy into disarray. After all, one of Trump’s signature policies was withdrawing the U.S. from the landmark Paris Agreement to limit global warming.

Get caught up on COP28

That tension was evident during COP28. On the very first day, negotiators made the unprecedented decision to adopt a so-called loss-and-damage fund to provide funding to developing countries facing the disastrous effects of warming that has already taken place. While the United Arab Emirates and Germany pledged $100 million each, the U.S. was roundly criticized for committing only $17.5 million, an amount climate justice advocates described as “paltry” and “shameful.”

Without mentioning U.S. responsibility explicitly, Reyes emphasized the need for developing countries to receive funding. Just $50,000 could go a long way to protecting 100,000 acres of carbon-dense forests in the Philippines, she told Mallory. “It’s a drop in the bucket for global commitments, but it’s going to be completely transformational,” she said.

Mallory nodded along, scribbling notes. Later on, Mallory told me that “everyone appreciates that none of this is going to happen unless we figure out mechanisms to finance.”

Mallory is one of several high-ranking U.S. officials attending COP28 to tout the Biden administration’s accomplishments, and she’s in Dubai for three days “lifting up the work we’re doing that is supporting the president’s agenda on climate change,” she said. Grist spent half a day with Mallory as she led panels on the administration’s climate initiatives, spoke to the press, and recorded a video with a young ocean-justice activist.

Mallory promoted two major U.S. initiatives on Saturday. That morning, she announced that the U.S. would join an international partnership promoting nature-based climate solutions, like tree planting and mangrove protection. (Healthy ecosystems can remove carbon from the atmosphere, and they can also function as natural infrastructure that protects landscapes from climate-driven impacts like flooding.) Later, she moderated an event about a Biden administration conservation initiative called America the Beautiful, through which the president outlined ways to conserve 30 percent of the country’s land and water by 2030. (The commitment is in line with the so-called 30 by 30 goal codified in an international pact signed by many other countries, but the U.S. Congress has never ratified that convention.)

But while Mallory was touting the president’s initiatives, a group of Republican lawmakers were meeting with world leaders and emphasizing their country’s position as one of the world’s top fossil fuel producers. Earlier in the week, Republicans fired off statements condemning Vice President Harris’ commitment to provide $3 billion to the Green Climate Fund, the largest international fund to support climate projects in developing countries.

“I am appalled that the Biden administration will pledge billions more of taxpayer dollars, money that Congress has not even provided, to yet another bloated, mismanaged, and ineffective slush fund that will do nothing to change the temperature of the planet,” said Representative Mario Díaz-Balart, a Republican from Florida and chair of an appropriations subcommittee on state and foreign operations, which has jurisdiction over international climate spending.

Meanwhile, at the media center, reporters found postcards with the acronym IRA, a reference to the Inflation Reduction Act, the landmark 2022 U.S. law that is expected to cut the country’s carbon emissions by roughly 45 percent, putting Paris Agreement targets within reach. The postcard rebranded the IRA as “Irresponsible Reckless Alarming” and included a QR code that linked to a report by Republican lawmakers titled “IRA Will Make the United States Poorer and China Richer.”

“It’s so hard when you’re depending on Congress actually coming around to support exactly what you’re doing,” Mallory said. “What I personally hope is that when people see the efforts to deliver on the commitments that we’re making on dollars combined with the other acts we’re also doing, that you look at those as a package.”

Coons chairs the Senate appropriations subcommittee on state and foreign operations. His comments refer to $1.5 billion in climate finance that Congress appropriated last year, which led to the U.S. contributing an additional $1 billion to the Green Climate Fund earlier this year. The contribution came after years of U.S. disengagement from the Paris Agreement and international climate finance during the Trump administration, and it underscored the domestic challenges U.S. administrations face in fulfilling climate commitments.

Such complexities are little comfort to those in developing countries.

“I just don’t care,” said Harjeet Singh, the head of global political strategy with the international environmental group Climate Action Network. “For decades, the United States has masked its lack of genuine political commitment behind the veil of complex domestic politics.”

The U.S. government should have worked to inform its citizens of the country’s historical responsibility in causing and exacerbating the climate crisis, he said: “This negligence towards its international duties exacerbates the plight of vulnerable communities and developing countries, who bear the brunt of a crisis they did little to create.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline At COP28, Trump and GOP threaten Biden’s climate promises on Dec 12, 2023.