Even if you are not one of the 30 to 50 million people in the…

The post Guide to Plant-Based Milk Alternatives appeared first on Earth911.

Even if you are not one of the 30 to 50 million people in the…

The post Guide to Plant-Based Milk Alternatives appeared first on Earth911.

According to a new report, an adjustment of three degrees Celsius to the standard temperature of frozen foods could lead to a yearly reduction in carbon emissions equal to taking 3.8 million automobiles off the road, while still maintaining food product safety, a press release from Cranfield University, which contributed to the research, said.

Academia and industry are calling for modification of the current standard temperature, which dates from the 1930s.

“Food saved is as important as food produced,” the report said. “12% of global food production is lost annually due to the lack of cold-chains. If saved, this is enough to feed one billion people a year.”

The report, Three Degrees of Change, by an international team of researchers proposes raising the frozen foods standard temperature from minus-18 degrees Celsius to minus-15 degrees Celsius.

“Cooling technologies, such as refrigeration, air conditioning and fans, currently account for more than 7% of all GHG emissions. It is estimated that these emissions could double by 2030 and possibly triple by 2100. Moreover, hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) are the fastest-growing source of GHG emissions in the world because of the increasing global demand for space cooling and refrigeration,” the report explained.

The findings of the study are scheduled to be discussed on December 10 at the United Nations COP28 climate conference on Food, Agriculture and Water day, the press release said.

“It is feasible to use freezing processes as a tool to ensure food safety as microorganisms are completely inactive below -12°C. Microbial growth, the cause of food-poisoning and spoilage, is not therefore an issue in frozen food,” the report said. “Agricultural production fluctuates with the yearly seasons, causing peaks and troughs in supply that result in associated periods of food abundance and scarcity. Freezing food provides a method for helping to smooth out the effect of this seasonality, reducing the risk of hunger in the off-season troughs through the safe storage of excess produce at times of peak supply.”

The temperature adjustment recommended by the report would save about 25 terawatt hours annually — equal to 8.63 percent of the amount of energy the United Kingdom uses each year.

“Additionally, freezing food can help stabilise the price of some products by reducing the influence of seasonal shortages or surpluses on the market; thereby making food potentially more affordable and accessible as well as reducing tensions that can lead to social and political instability,” the report said.

Experts say the new standard would allow for a change in storage practices and the transportation of frozen foods without compromising food quality or safety, according to the press release.

“Meeting the challenges within our global food supply chain demands innovative solutions that [bring] together environmental sustainability with food security,” said Dr. Natalia Falagan, Cranfield University senior lecturer in food science and technology, in the press release. “Cold chains stand as a critical pillar in guaranteeing access to safe and nutritious food and this initiative improves the resilience of food systems and contributes towards global food security, in addition to driving sustainability.”

The post Adjusting Frozen Food Temperature Could Reduce Carbon Emissions While Improving Food Security, Researchers Say appeared first on EcoWatch.

In metropolitan areas around the globe, public transportation is going greener. Many cities are working towards eliminating greenhouse gas emissions by transitioning away from fossil fuels — which are responsible for roughly 75% of climate warming GHGs — to renewable energy, and electrifying bus fleets is a priority.

Diesel exhaust from fossil fuel-powered buses contributes to poor air quality in cities, resulting in particulate pollution and the production of ground level ozone. According to Environmental America, replacing all diesel-powered transit buses in the country would eliminate over 2 million tons of GHG emissions every year. Luckily, as technology improves, electric buses are becoming a more feasible option for cities and school districts, with buses operable in different temperatures and topographic areas.

These five cities are among the many paving the way toward electric powered public transit for all.

An electric bus in Chicago, manufactured by Proterra. Regional Transportation Authority

The Chicago Transit Authority has made a big step toward its goal of transitioning to all-electric buses by 2040. In June, the CTA bought 22 new 40-foot buses, bringing the total number of electric buses on the Chicago streets to 47. The windy city has been a test of how battery-electric buses would work in very cold weather. Lithium-ion batteries aren’t as efficient in the cold and get drained much faster — the CTA reports that buses lose about 8% of their charge over 10 miles. Fast charging sites with roof plugins along bus routes have made electric buses possible despite the frigid winter weather.

Chicago’s entire fleet amounts to about 1,900 buses, so switching them out is no easy task — especially since each electric bus costs over $1 million. However, the CTA calculated that electric buses cost less to operate once they’re on the road, amounting to about $2.01 per mile compared to $3.08 for diesel buses. They report that they’ve been prioritizing electric bus services in neighborhoods with high levels of air pollution, which are often communities of color and lower income areas. This summer, the CTA began featuring all-electric buses along the #63 route that serves Chicago’s South Side.

The Mile High City has been cracking down on carbon emissions. In 2018, Denver replaced their entire Mallride fleet — the free buses that go through downtown Denver — with 36 zero-emission electric buses. The transition to electric hasn’t been easy, however — the city canceled an order for 17 new electric buses in April after determining that they didn’t have the space to charge and maintain them. In spite of the difficulties, the Regional Transportation District (RTD) has set a new goal of achieving net zero emissions by 2050.

Electric school buses are where Colorado — including Denver — has had great success. The state will soon double their electric school bus fleet using a mixture of federal and state funding, adding 67 new electric school buses to the 52 that have already been purchased. Denver Public Schools will receive some of the funds, as will schools in the Boulder Valley, Monte Vista, Poudre, and Steamboat Springs school districts.

An electric bus in downtown Boise, Idaho on June 19, 2022. Ac530 / CC BY-SA 4.0

Boise’s electric buses are superheroes in the community — literally. The Charging Champ, the Pollution Solution, the Clean Green Machine, and the Silent Rider take to the streets, their facades painted in comic book style designs. The Valley Regional Transit — which serves Boise and other communities in the Treasure Valley region — even made a comic book about the climate-change-fight buses who want to “stop smog in its tracks, and put an end to congestion once and for all.”

The Valley Regional Transit (VRT) doesn’t get state funding, so it relies on money from other agencies. The Idaho state legislature — which is 83% Republican — has presented barriers to getting electric buses on the road, and passed a law that restricts the use of property taxes to fund road construction and transportation costs. Despite the hurdles, the VRT is working to switch out their 54 diesel vehicles with electric. So far they have 12 on the road, 4 of which are the iconic superheroes. They hope that the flashy design — rather than the typical ad-splattered sides of buses — will entice more people to choose to ride the bus, combatting the high congestion and air pollution in the area.

King County Metro was an early adopter of electric buses, and is moving towards a renewable energy-powered fleet by 2035 starting with its 40 electric buses currently in service. In a city on the water, however, there’s also maritime travel to consider. Washington State Ferries are the largest emitters of greenhouse gases in the state transportation system. Hybrid ferries are getting phased in starting in 2023, with the goal of reducing carbon emissions on the water by 76%.

Seattle’s big electric initiative is with Amtrak, which is rolling out its first electric bus. Soon, it’ll run on the very popular Cascades line between Bellingham and Seattle, replacing one of the diesel-powered buses used for this purpose. The bus will be able to make the whole journey on a single charge — an impressive feat for a 200-mile round trip.

An electric New York City bus participates in the Hometown Heroes tickertape parade on Broadway in honor of essential workers who endured the COVID-19 pandemic, on July 7, 2021. Metropolitan Transportation Authority

8.5 million is a lot of people to move, but if anyone is up to the task, it’s New York. Home to the largest public bus system in North America, 60 battery electric buses total are entering service in the city in 2023, and further infrastructure will be installed at 5 depots. Between 2025 and 2026, the MTA plans to enter 470 more electric buses into service, with the goal of all 5,800 of the city’s buses transitioning to electric by 2040. It’s estimated that this transition would avoid emitting 500,000 metric tons of CO2 yearly, helping with statewide efforts to reduce carbon emissions.

The current 2020-2024 capital plan has over $1 billion allocated to electric buses. In a city where daily ridership of subways and buses is 3.6 million, the transition would make the MTA’s electric fleet the largest of its kind in North America. Buses have less ridership than subways, but they’re still an efficient way to travel — bus improvements and new lines have recently been deemed the cheapest and most efficient way to reach LaGuardia airport (over subways), so the city will be in need of more buses than ever.

The post 5 Cities Leading the Charge Toward Electric Bus Transportation appeared first on EcoWatch.

According to a new report led by professor Tim Lenton from the University of Exeter’s Global Systems Institute, in collaboration with more than 200 researchers worldwide, Earth’s climate has already warmed enough that humans are at risk of triggering five global “tipping points” that could have disastrous effects on the planet.

If the world warms more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, the likelihood of breaching these tipping points increases, as does the chance of crossing others, reported New Scientist.

“Triggering one tipping point could trigger another in a kind of dangerous domino effect,” Lenton said, as New Scientist reported.

The report, Global Tipping Points, was assembled by researchers in 26 countries from more than 90 organizations.

Lenton referred to a tipping point — a slight change in a system that causes drastic changes that are difficult to reverse or are even irreversible due to an intensifying feedback loop — as akin to leaning backwards in a chair.

The five tipping points laid out in the report are: the melting of the ice sheets in West Antarctica and Greenland; the rapid thawing of large swaths of Arctic permafrost; the slowing of the North Atlantic subpolar gyre; and tropical coral reef die-off.

“[T]hese tipping points in the Earth system could, in turn, trigger damaging tipping points in societies, things like food security crises, mass displacement and conflicts. Stopping these threats is possible, but it’s going to require urgent global action,” Lenton said, as reported by WION.

The North Atlantic subpolar gyre is an important circular ocean current associated with the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC), New Scientist said. AMOC is a large system of currents that circulates water in a long cycle from north to south within the Atlantic Ocean, bringing warmth and nutrients to parts of the planet.

According to David Armstrong McKay, a research impact fellow at the University of Exeter, there is evidence that the subpolar gyre could slow down or stop sooner than AMOC.

“[The slowing of the subpolar gyre] could happen within about 10 years. It would have pretty major impacts across both sides of the Atlantic,” McKay said, according to New Scientist. “It would cause regional cooling and affect agriculture in Europe and North America, and change the patterns of extreme weather events.”

Manjana Milkoreit, who contributed to the report and is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Oslo, said if we want to stop some of these tipping points, we need to do it right away.

“For some tipping points, we have a very short window for preventive action open right now which might close as soon as the 2030s,” Milkoreit said, as New Scientist reported. “We think that the prevention of Earth system tipping points should be the core objective of governance efforts because of the scale and severity of the threats that they represent, their cascading potential and the irreversibility of many tipping processes on relevant human timescales.”

The collapse of fisheries and the die-off of mangrove forests and seagrass meadows are some of the other tipping points.

The report points out that whether or not some systems have tipping points, how far off they are and what the potential impacts would be remains unclear.

Milkoreit emphasized that reducing and eliminating greenhouse gas emissions as quickly as possible is still the best way to limit global heating and reduce the chances of triggering these dangerous tipping points. Additional actions like stopping Amazon deforestation would also help, Milkoreit said.

“Even with a profound acceleration of action, some Earth system tipping points may be unavoidable,” Lenton pointed out. “But still there are things we can do to mitigate the risk they pose by reducing the vulnerability of people to the impacts coming from them.”

The post 5 Major Climate Tipping Points Could Be Triggered Within a Decade, Report Warns appeared first on EcoWatch.

Impossible Foods, Inc., a company known for its plant-based burgers, is adding hot dogs to its lineup starting in 2024. Some New Yorkers will be able to try them this month before they officially hit stores.

The plant-based hot dogs will be the company’s first new product of 2024, although the exact date that this product will be available in restaurants and grocery stores has yet to be revealed.

Impossible’s hot dogs have half the amount of total fat and saturated fat compared to a top beef hot dog brand found in restaurants, according to a company press release. The hot dogs also contain 12 grams of plant-based protein.

The company says that these hot dogs are not made with added or synthetic nitrates or nitrites like some hot dogs made from animals, although they do contain natural nitrates and nitrites from cultured celery powder.

Nitrates and nitrates are naturally occurring in soil and plants but are sometimes added in food processing as preservatives, according to the European Food Information Council (EUFIC). Excessive nitrate levels may limit how red blood cells transport oxygen and may contribute to nitrosamine formation; some nitrosamine compounds may be carcinogenic. Nitrates and nitrites may convert to nitrosamines when cooked at high heat, Healthline reports.

In addition to creating a plant-based alternative to animal-based hot dogs that is lower in fats and high in protein, Impossible Foods says the new hot dog product will be more sustainable compared to hot dogs made from animals. According to the company, the hot dogs are responsible for 84% less emissions, and require 77% less water and 83% less land compared to producing a beef hot dog.

“Hot dogs are an undeniably classic part of American culture and not to mention, they’re a burger’s best friend. It’s long been a priority to add them to our product portfolio,” Peter McGuinness, CEO and president of Impossible Foods, said in a statement. “Our adaptation replicates that quintessential hot dog taste, while offering consumers a nutrient-dense product that’s better for the planet. We want people to see that there’s really no compromise when you choose Impossible products.”

The Impossible Hot Dogs will be joining several other existing meatless items, such as Impossible beef, beef lite, meatballs, spicy chicken nuggets, and patties, regular chicken nuggets and patties, and chicken tenders, all made with plant-based ingredients.

Although the hot dogs won’t be available for purchase at restaurants and grocery stores until next year, Impossible Foods is hosting a pop-up in Midtown New York City on Dec. 16 from 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. EST for those who want to preview the product early. Impossible will be giving away its plant-based hot dogs for free, while supplies last. Anyone interested in trying the product can follow along on the company’s Instagram for the pop-up address details.

The post Impossible Foods Announces Plant-Based Hot Dogs appeared first on EcoWatch.

As negotiators at the COP28 climate summit in Dubai debate calls for a global phaseout of fossil fuels, a record number of fossil fuel lobbyists have filled the gathering’s hallways and conference rooms: More than 2,400 conference delegates have ties to the fossil fuel industry, according to a new report from Kick Big Polluters Out, a global coalition of more than 450 nonprofits and advocacy organizations that oppose the fossil fuel industry’s influence on climate policy. The data is only available thanks to new transparency requirements adopted by the United Nations at the behest of climate advocates, who have argued that the fossil fuel industry takes advantage of lax reporting standards to push its agenda at the annual COPs.

The sheer number of lobbyists at the conference — about 1 lobbyist for every 40 attendees overall — has disturbed many activists and world leaders pushing for a fossil fuel phaseout. But just as concerning is how little information is available about why these lobbyists come to Dubai. They gain access to the conference under the auspices of national governments that invite them, trade groups that represent their financial interests, and business organizations that their companies are members of, but it’s difficult to know exactly how they try to influence the talks once they arrive. Organizers with Kick Big Polluters Out say that lobbyists use their association with nondescript-sounding trade groups to hide their direct advocacy on behalf of oil, gas, and other industries.

“For us, this undue influence constitutes a form of corruption and should be much better regulated,” said Brice Böhmer, the climate and environment lead at Transparency International, a German anti-corruption organization founded by former World Bank employees. “This is urgent, as it has been delaying and diverting climate ambition and action.”

Many fossil fuel advocates identified in the report are attending as part of national government delegations, and some even work for state-owned corporations that produce oil and gas. More than a dozen members of the Kuwaiti delegation, for instance, are affiliated with the Kuwait National Petroleum Company, an oil refiner owned by the Kuwaiti government. The delegation from Botswana, meanwhile, includes four representatives who are affiliated with a large coal mine that is jointly owned by the Botswanan government and the De Beers diamond company.

A large number of lobbyists are arriving at COP28 with “host country badges,” indicating they are attending as guests of the United Arab Emirates itself. The president of COP28, Sultan Ahmed Al-Jaber, is also the head of the Emirati oil company Adnoc, and several other representatives from that company are attending under host badges. The host country guests also include senior executives from oil field company Baker Hughes, the petrochemical company Oxy, and Saudi Arabia’s state-owned energy company, which refines and exports the country’s vast oil reserves. Perhaps the most notable member of the host delegation is Darren Woods, the CEO of ExxonMobil, who has touted the company’s hydrogen and carbon capture investments while at the conference.

Activists argue that, even when fossil fuel interests are not invited at the behest of national governments, they can disguise their large presence at COP talks by sending their members under a variety of different trade groups and organizations, rather than sponsoring their own delegations. ExxonMobil, for instance, has at least 17 representatives at COP28 other than Woods, but they are all enrolled under groups such as the United States Council for International Business and the International Council of Chemical Associations.

As the trade groups tell it, they’re trying to give their member companies a voice in complex negotiations. Many such trade groups arrive at COP with a list of actions or goals they’d like to see implemented. The United States Council for International Business, for instance, sent an open letter to U.S. climate envoy John Kerry last month that outlined its agenda for the conference. The letter promised that the group would “engage constructively” in talks about how to measure and enforce net-zero pledges, but it also noted that the group was “concerned” that enforcement of those pledges “risks producing a chilling effect on future voluntary climate action initiatives.”

In the eyes of groups like Kick Big Polluters Out, this amounts to deception — after all, the group’s membership includes Shell, BP, and ExxonMobil.

“Trade associations have always been one of the primary ways big polluters influence these negotiations,” said Rachel Rose Jackson, a researcher at the nonprofit Corporate Accountability. “They provide a direct route for them to influence the talks without having to be super clear about who they are.”

The largest and most influential of these trade groups, with 116 representatives, is the International Emissions Trading Association, or IETA, which touts itself as “a nonprofit business group championing the power of high integrity markets to reach net-zero targets.” The group advocates for the creation of markets that allow countries and companies to buy, sell, and trade carbon offsets to neutralize their own emissions. This carbon accounting is at the heart of many “net zero” emissions pledges, in which a company such as an airline will pay someone to undertake an activity that reduces atmospheric carbon — for instance, by protecting an endangered forest from logging — as a way of canceling out the emissions of the jet fuel it burns to fly its planes.

Among the members of the IETA delegation this year are representatives from BP, Shell, the French oil giant TotalEnergies, and the Norwegian state-owned oil company Equinor. It’s not just oil majors, either: Morgan Stanley, Bank of America, Volkswagen, and the Anglo-Australian mining conglomerate Rio Tinto are also attending under IETA’s aegis.

The fact that so many fossil fuel advocates are attending the conference under the auspices of IETA may be a sign that industry interests see carbon markets as an important part of their long-term business strategy. The creation of a voluntary trading system for carbon offsets would ease some pressure on these companies to reduce their direct greenhouse gas emissions. But new research has cast doubt on the validity of the carbon offsets that sustain these markets: According to one estimate, more than 90 percent of the rainforest conservation credits issued by the carbon market company Verra may not exist at all.

IETA was founded in 1999 by a group of firms that included multiple oil majors, notably BP, and today it is funded by several dozen banks, oil companies, and other large corporations. It now has hundreds of members including Chevron, ExxonMobil, the mining conglomerate Glencore, and livestock giant Cargill. The association describes itself as a “purely business” lobbying effort, but Corporate Accountability says it “exists to ensure that climate policies don’t negatively impact the profits of Big Polluters.”

A spokesperson for IETA declined to discuss the identity of individual delegation members.

This is far from the first time that IETA has dominated a U.N. climate conference. In 2005, it sent more than 400 delegates to the conference in Montreal at a time when the average size of a government delegation was just 22 members. In turn, IETA emerged with a big victory as countries agreed to formalize a carbon-trading scheme. Andrei Marcu, an early president and CEO of IETA, advised the national delegation of Panama at COP23 in 2017, attempting to influence the country’s engagement in climate talks even as he also pushed the interests of big oil companies. And at the 2019 conference in Madrid, the body sent 129 delegates, some of whom handed out pins that said, “All I want for Christmas is Article 6,” referring to an item in the Paris agreement that lays the groundwork for a global carbon market.

The stakes at COP28 are high. After years of work, negotiators hope to reach a global consensus about what offset projects should count under the U.N.’s Article 6 carbon market and about how to monitor the long-term success of offset projects. In a position paper released ahead of the summit, the IETA noted that this year’s Article 6 negotiations presented “the opportunity to avoid extreme politicization and focus on key decisions.”

Bohmer, of Transparency International, said that the new reporting requirements will make this year’s COP somewhat more transparent than previous ones, but he argued that there’s still room for lobbyists to push their own agendas at the talks.

“Some of the requirements are optional and declarative,” he said of the new standards. “This is far from a framework allowing the detection and management of conflicts of interest.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Why are there so many fossil fuel lobbyists at COP28? on Dec 6, 2023.

It couldn’t be simpler. Cherry tomatoes go into a baking dish with olive oil, salt, and pepper — and at the center of it all, a full block of creamy, salty feta cheese. Into the oven it goes to get all melty and roasty and delicious. Then add garlic, fresh basil, and cooked pasta, and you’ve got dinner.

That recipe, originally by Finnish blogger Jenni Häyrinen, took off on TikTok and sparked a feta craze that has affected real-world demand and supply — so much so that the New York Times dubbed the phenomenon “the TikTok feta effect.” Stores couldn’t keep it on shelves, and cheesemakers expanded production to keep up. Häyrinen wrote that feta sales went up 300 percent in Finland after she first posted the recipe in 2019.

#FetaPasta has racked up 1.4 billion views on TikTok as of this writing, with droves of users recreating the viral recipe and adding their own twists. As a casual TikTok user, I have watched the yearslong feta obsession, and similar fads like the recent unlikely rise of cottage cheese, and wondered: Could the platform’s power to influence food trends help inspire a shift toward more climate-friendly eating? Could a humble vegetable — or better yet, a low-impact, vegan protein or a perennial grain — experience the TikTok feta effect?

![]()

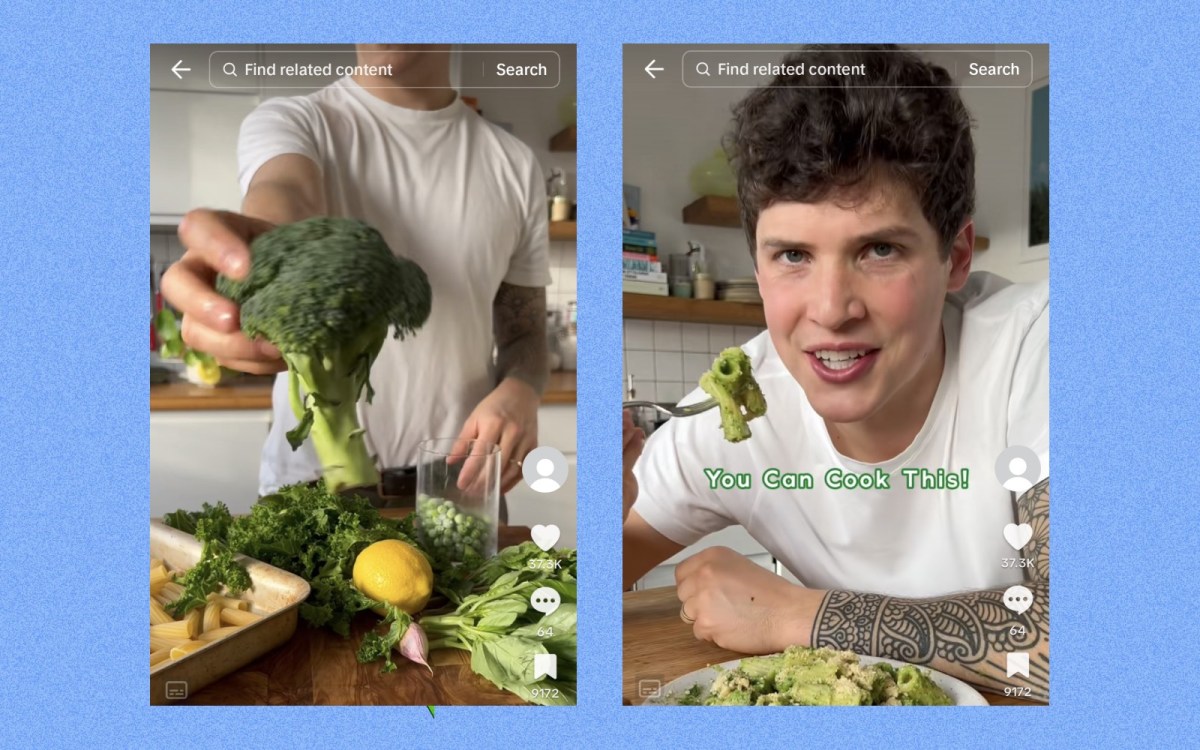

TikTok creator Max La Manna is a low-waste, plant-based chef with about 150,000 followers on the platform. I asked him what made the feta recipe so successful, and what he thinks about when trying to make his recipes take off on the platform.

“There’s a multitude of different variables that come into play to make a video successful,” La Manna said. One factor he nods to is the ability to capture a viewer’s attention quickly. On TikTok, a user might scroll from a recipe to a makeup tutorial to a montage of funny cats, all in the span of seconds. Creators are trying more and more to hook people in during the very first few seconds of a video, La Manna said. “It’s all these components. It’s the delivery, it’s what’s being filmed, it’s how it’s being filmed.” And, he adds, the personality of the host or creator also plays a big role in how people will respond to a given video.

Screenshots from a video where Max La Manna demonstrates a pasta recipe starring broccoli, kale, and herbs — stems and all. Max La Manna

Cooking videos are, in many ways, perfectly suited to these aspects of TikTok’s ethos. The great appeal of the TikTok cooking video is that it invites you into another person’s kitchen and shows you, in quick-moving steps, exactly how something is made. If that something is an easy, low-effort dish using ingredients you can get at the supermarket — like feta or cottage cheese — all the better. In describing the proliferation of the feta pasta, the New York Times noted that “the videos are just as likely to be made by influencers as by teenagers without large followings.”

Of course, another factor is that the dish in question has to actually be appetizing. When I asked Katie Burdett, a farmer and recipe creator with 350,000 TikTok followers, about the success of the feta pasta, she noted simply, “You know, feta baked down with herbs and tomatoes is really good.” (I’ve tried it. It is good.)

Still, it’s famously impossible to predict, or control, what trend or ingredient or single piece of content is going to go viral. “I’ve been lucky to have many viral videos, and sometimes they’re confounding to me,” Burdett said. One of her most popular formats is ASMR harvest videos. Her recipes haven’t tended to perform quite as well, and she suspects part of the reason is that the algorithm likes to see her staying in one lane.

TikTok also has features that can quickly amplify momentum and lift up some surprising things. Copycats and reaction videos or “duets” can turn a minor trend into a sensation as other creators try to piggyback on something that is already working. “When one viewer, one creator sees a video doing well, then they try to spin off of that and make something,” La Manna said. “‘Oh, that cheese video did really well. I’m gonna do something similar that’s using cheese.’” It happens a lot with cooking videos, because creators can also add their own flare to a trending recipe.

In a way, the feta effect may be a combination of creator skill, luck, and a volume game. More videos = more chances for one to take off. In that case, the odds of a shortage-inducing craze for a vegetable or other climate-friendly food are rising every day, thanks to the growth of plant-based creators on TikTok — a trend in and of itself.

![]()

However, both Burdett and La Manna offered that in hunting for a climate-friendly food sensation, I may be asking the wrong question altogether.

That ability of viral videos to inspire people to try new things is a positive, Burdett believes — and there’s no reason that couldn’t happen for low-impact ingredients. But, she added, as a farmer, she has concerns about the pendulum swing of food trends. Many crops take a long time to grow or produce, and farmers often plan several years in advance. If and when a fad fades, it can pose problems for producers, she said. “I hope that there’s not an overcorrection on the side of a maker, then, who … makes a lot of investments in their infrastructure or livestock or all different kinds of things, and then the next year that trend’s over.”

Rather than trying to increase consumption of a particular food, climate-friendly TikTokkers may prefer to help people reduce overconsumption. “I think that I am seeing more of a trend from a lot of the food content creators leaning more in a sustainable direction,” Burdett said.

Many of her recipe videos focus on seasonal eating and how to use up the harvest. That seasonality is one thing that sets fruits and vegetables apart from ingredients like feta — some veggies do, in a sense, go viral when their moment arrives. “That’s mostly when I hear from people,” Burdett said. “‘Oh my God, I have way too much zucchini. And I don’t want it to go to waste, I put all this time and energy and money into growing this and so, like, help.’” She enjoys that back-and-forth with her followers and the opportunity to offer recipes for specific scenarios. “I think that it can be really important to use that platform to give people resources to empower them,” she said.

Katie Burdett with a lettuce harvest from her home garden in Michigan. Courtesy of Katie Burdett

La Manna echoes that sentiment, and emphasizes the importance of cooking resourcefully and using up what you have — not only to avoid food waste, but also to avoid wasting money. He recently published a cookbook, You Can Cook This!, inspired by two years’ worth of asking his digital community about the ingredients they most often throw away. The book focuses on 30 of the most commonly trashed ingredients, from broccoli stems to bagged leafy greens, and offers recipes to keep them from going to waste. If one of these recipes were to “go viral,” we would never see its ingredients fly off the shelves as feta has done — that’s the opposite of the point.

All that said, if La Manna had to nominate one ingredient to be the next feta, his candidate is stale bread. From breakfast (french toast!) to dessert (bread pudding!), old bread has tons of easy and potentially viral uses that ought to keep it out of the compost bin, he said — it can thicken sauces, it can replace nuts in a pesto, it can even be the base for a hearty and thrifty soup. “Let’s make stale bread sexy.”

— Claire Elise Thompson

Andrée Nieuwjaer, a resident of Roubaix, France, poses in front of her pantry filled with reusable glass jars of staple foods, holding a sponge she made out of potato bags. Nieuwjaer’s household is one of 800 to participate in a program called Roubaix Zéro Déchet, or “Zero-Waste Roubaix” — an educational initiative that gives residents tools to reduce their household waste. In a story published today, Nieuwjaer told Grist’s Joseph Winters that she would be eating for free all winter, with imperfect or slightly-past-its-prime produce she sourced for free and then preserved. She estimates that she saves around 3,000 euros a year from her waste-reduction efforts.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline TikTok made cottage cheese cool. Can it do the same for climate-friendly eating? on Dec 6, 2023.

This story is co-published with The Guardian and supported by The Heinrich Böll Foundation.

Andrée Nieuwjaer, a 67-year-old resident of Roubaix, France, is what one might call a frugal shopper. In fact, her fridge is full of produce that she got for free. Over the summer, she ate peaches, plums, carrots, zucchinis, turnips, endives — all manner of fruits and vegetables that local grocers didn’t want to sell, whether because of some aesthetic imperfection or because they were slightly overripe.

What Nieuwjaer couldn’t eat right away, she preserved — as fig marmalade, apricot jam, pickles. Reaching into the depths of her refrigerator in September, past a jar of diced beets that she’d preserved in vinegar, she tapped a container of chopped pineapple whose shelf life she’d extended with lemon juice: “It’ll last all month!” she exclaimed. Just a few inches away, two loaves of bread that a nearby school was going to get rid of lay in a glass baking dish, reconstituted as bread pudding. A third loaf was in a jar in the cupboard, transformed into bread crumbs that Nieuwjaer planned to sprinkle on a veggie casserole.

With everything she’d stocked up, Nieuwjaer was all set on groceries for the next few months. “I’m going to eat for free all winter,” she said in French, beaming.

Nieuwjaer is part of a worldwide movement known in French as zéro déchet, or zero-waste. The central idea is simple: Stop generating so much garbage, and reap the many intertwined social, economic, and environmental benefits. Rescuing trash-bound produce, for example, stops food waste that can release potent greenhouse gases in a landfill. Making your own shampoo, deodorant, and other beauty products reduces the need for disposable plastic bottles — plus, it tends to use safer ingredients, meaning less danger for fish and other wildlife.

But Nieuwjaer didn’t just one day decide to join the movement; she was drawn into it as part of a local government experiment in waste management. In 2015, the city of Roubaix launched a campaign to reduce litter by teaching 100 families — including Nieuwjaer’s — strategies for cutting their waste in half. Similar efforts may soon be repeated across France as cities and regions begin striving to meet (and exceed) the country’s ambitious waste-reduction goals. At the heart of their efforts is a fundamental question: How do you get citizens to change their behavior?

Most Americans know France as the land of fine wines and cheese. But among a more niche audience, the country is also known as a zero-waste leader. Besides producing one of the world’s most famous zero-waste influencers, Bea Johnson — the “priestess of waste-free living,” according to the New York Times — France has passed some of the developed world’s most ambitious waste-reduction policies. It was the first country in the world to ban supermarkets from throwing away unsold food, and one of the first to enshrine “extended producer responsibility” into law, making big polluters financially responsible for the waste they create, even after their items are sold.

In 2020, France passed a landmark anti-waste law that laid out dozens of objectives for waste prevention, recycling, and repairability, including a national goal to eliminate single-use plastic by 2040. The law banned clothing companies from destroying unsold merchandise, required all public buildings to install water fountains, and proposed “repairability index” labels for certain electronic products. At the time, the law was praised as “groundbreaking,” and several of its provisions were hailed as the first of their kind.

According to France’s waste prevention action plan for 2021 to 2027, finalized in March by the administration of President Emmanuel Macron, cutting waste will yield myriad co-benefits, from boosting biodiversity and improving food systems to mitigating climate change. One estimate from the nonprofit Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives says that a comprehensive zero-waste strategy that includes better material sorting, more recycling, and source reduction — in essence, producing fewer unnecessary things — could reduce waste-sector greenhouse emissions by 84 percent globally.

Achieving all these benefits, however, will require more than proclamations from Paris. According to France’s Ministry of Ecological Transition, the national anti-waste plan is meant to filter down through the levels of government before ultimately manifesting at the local level. The national plan requires regions to develop their own sub-plans, and asks small-scale waste management authorities to “enable the implementation” of France’s bigger-picture waste agenda.

Really, though, the transformation envisioned by France’s zero-waste advocates requires even more granular action — from boutiques, from supermarkets, from restaurants. Keep peeling back the layers and you end up with individual people like Nieuwjaer, who must be nudged, incentivized, or told to change their behavior to accommodate waste reduction — even if they’re not all as enthusiastic as she is. As the country’s 2021 to 2027 action plan says, “Reducing our waste requires everyone,” suggesting that an all-encompassing culture shift will be needed to achieve the national government’s goals.

This is the task that many French cities and waste collection authorities are now confronting — how to change individual people’s behavior so that it conforms with France’s vision for waste reduction. Some of the most ambitious places have become incubators: notably Roubaix, whose voluntary, education-based approach has drawn international attention. Last year, the European Commission named Roubaix as one of the top 12 places in the European Union with the greatest potential for “circularity,” a term referring to systems that conserve resources and minimize waste generation.

There’s also the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region north of Bordeaux, where a regional waste management authority called Smicval is experimenting with more structural interventions like moving garbage bins and charging people differently for waste collection. Pauline Debrabandere, a program manager for the nonprofit Zero Waste France, called Smicval one of the country’s “biggest pioneers.”

The projects illustrate the need for complex behavior-change strategies that both educate people and alter the social and environmental contexts in which they make their decisions. And they hold lessons for communities across the globe looking to implement their own waste-reduction programs. Debrabandere put it this way: While you need rules and incentives to “create the conditions” for waste reduction, you also need to convey its benefits and ensure widespread participation. “You have to raise awareness.”

When Alexandre Garcin dreamed up Roubaix Zéro Déchet — French for “Zero-Waste Roubaix” — as a candidate for city councilor in 2014, it wasn’t so much sustainability that inspired his vision; it was cleanliness. Roubaix’s litter problem was top of mind for everyone that year, and Garcin’s big idea was to address it through waste reduction. Rather than cleaning up more and more trash off the city’s streets, why not produce less garbage in the first place?

This was easier said than done. Roubaix is a famously poor, postindustrial city that belongs to the Métropole de Lille, a network of communities organized around the major city of Lille in northern France. This superstructure coordinates infrastructure that crosses town lines, such as public transit and waste management. According to Garcin, the métropole wasn’t interested in funding and implementing his zero-waste initiatives. To cut down on waste generation, Roubaix would have to get creative — by asking residents to volunteer.

Once he was in office, Garcin mailed leaflets to Roubaix residents seeking 100 volunteers to participate in a free, yearlong pilot program that would teach them how to live waste-free — or, at least with less waste than usual. These familles zéro déchet, or zero-waste families, would receive training and attend workshops on topics like making your own yogurt and cleaning with homemade products, with the goal of halving their waste by year’s end. Volunteers weren’t offered any direct financial incentives to participate — only the promise of helping solve the litter problem and protecting the environment. Using a luggage scale — a “really, really, really important” part of the program, according to Garcin — they would periodically weigh their weekly trash and report it back to the city.

The luggage scale forced people to recognize the impact, and literal weight, of their consumption choices, Garcin explained. “Physically, you have the sense of how heavy it is.”

The program Garcin designed exemplified what behavioral scientists call an “information-based” approach to change, which builds understanding and awareness through unambiguous instructions, forums, meetings, trainings, and feedback. Philipe Bujold, behavioral science manager for the international environmental nonprofit Rare, described this as a “tell them” strategy, in contrast with other tactics to induce behavior change, including through incentives (“pay them”) or rules and prohibitions (“stop them”). Josh Wright, executive director of the behavioral science consulting firm Ideas42, also lauded Roubaix Zéro Déchet for creating an identity around zero-waste and assigning families quantitative waste-reduction targets — strategies that have proven to be effective in other contexts.

Much of what Roubaix told residents to do was actually pretty straightforward — for example, “don’t buy more food than you can eat.” But that was kind of the point. According to Garcin, it’s actually “not that difficult” to halve a household’s waste production. Composting alone is enough to get you most of the way there, since organic waste makes up about a third of the average French family’s municipal waste by weight. Another third is glass and metal, a significant chunk of which can likely be kept out of the landfill through recycling, and 10 percent is plastic, much of which can be avoided by finding reusable alternatives to plastic grocery bags, cutlery, packaging, and other single-use items. According to the United Nations Environment Programme, half of all the plastic produced worldwide is designed to be used just once and then thrown away.

“The idea was to help everyone change his consumption at the place where he’s ready,” Garcin explained, whether that meant eating fewer takeout meals or switching to homemade laundry detergent. Through these minor lifestyle changes, the earliest participants in Roubaix Zéro Déchet’s family program saved an average of 1,000 euros (about $1,100) per year, according to Garcin. Seventy percent of them cut their waste generation by 50 percent, and one-quarter reduced it by more than 80 percent.

Of course, some participants embraced zero-waste more enthusiastically than others and therefore reaped even greater rewards. Nieuwjaer, for example, would eventually cut her landfill-bound waste by so much that nine months’ worth would fit on her kitchen scale. All told, Nieuwjaer says she saves about 3,000 euros a year because of her zero-waste habits.

One drawback of an information-based strategy for behavior change, however, is that it tends to have limited reach while working very well on a small slice of the population — the “pioneers,” as Garcin called them, in this case referring to people who are exceptionally attentive to their health, environmental footprint, or personal finances. Since 2015, many of Roubaix Zéro Déchet’s most enthusiastic participants have been those who were already interested in wasting less, even before they heard about the program.

Amber Ogborn, for example — an American who moved to Roubaix with her family in 2012 — said her decision to sign up as a famille zéro déchet in 2019 was influenced by a trip to a waste incinerator, where she saw garbage trucks unloading a “mountain of trash” to be burned. Ogborn is now all-in on zero-waste, thanks in large part to training she received from Roubaix Zéro Déchet. In addition to other new habits, she now maintains three separate composting systems, including one dedicated to the cat litter and dog droppings that she was tired of having to throw in the trash.

“It’s kind of gross,” Ogborn said. “But I thought, ‘You know what? This is one small thing that we could do.’”

Another die-hard participant is Liliane Otimi, who was already running a Roubaix-based environmental nonprofit called Lueur D’Espoir — “glimmer of hope,” in English — when she enrolled her 10-person household in the city program in 2018. Otimi was passionate about climate change and resource conservation and wanted to embody more of her values in her daily life — especially after a trip back to Togo, the West African country where she grew up. In Lomé, the capital, Otimi said she was “shocked” to see how quickly people went through plastic water bottles and then littered them onto the street. Through Roubaix Zéro Déchet, Otimi learned how to buy cleaning products in bulk, how to do weekly meal prep, and how to plan her grocery shopping so she only buys as much food as her family will be able to use.

“It’s beautiful to live in line with our values,” said Michaela Barnett, a behavioral scientist and founder of KnoxFill, a startup focused on reducing waste, acknowledging Roubaix Zéro Déchet’s allure among a particular demographic.

However, it’s one thing to give “pioneers” like Otimi and Ogborn the tools to live their best zero-waste lives, and quite another to bring all of Roubaix’s residents into the movement. Not everyone will value resource conservation — let alone act on those values — even if you tell them why they should. This is a key reason why behavioral scientists advocate for behavior-change strategies that are more complex than just “tell them” alone. “We generally think of education as a necessary but not sufficient type of intervention,” Wright said. (Incidentally, scientists used to think that an information deficit was the reason for climate inaction. Unfortunately, this has proven not to be the case.)

The 800 families that Roubaix has trained since 2015 likely represent the most easily convincible slice of the city’s population — an estimated 1.8 percent of its 100,000 residents, assuming an average family size of 2.3 people. It’s taken Roubaix nine years to reach this many people, and the rest of its residents will likely be harder to convert.

To be sure, there is more to Roubaix Zéro Déchet than “tell them,” and the city is doing what it can to broaden its reach beyond those most inclined toward zero-waste. For example, the program leans on social influences through advertisements, festivals, and community meetups, and spokespeople like Bea Johnson, the zero-waste social media influencer. (When she was invited to give a talk in Roubaix in 2015, the event was so popular that the city had to change locations three times in order to accommodate more attendees.) Roubaix also promotes the stories of its most successful familles zéro déchet in local, regional, and national media outlets — a strategy that has drawn so much positive press that the city’s communications director said in 2016 that zero-waste had become “my Eiffel Tower.”

What’s more, City Hall has brought zero-waste practices and education into all of Roubaix’s public schools and is trying to nurture a network of zero-waste merchants — including restaurants, grocers, copy shops, and more — that adhere to a set of best practices for waste reduction. The municipal government is also expanding a voluntary community composting program independent from the métropole, and is turning two buildings into zero-waste incubators — essentially, hubs for small and growing businesses that are focused on waste reduction. One of the buildings, a former textile factory, already hosts a company that saves bicycles from being sent to the landfill.

Debrabandere, with Zero-Waste France, said Roubaix is remarkable for what it has accomplished with such limited means. Despite its tight municipal budget and lack of control over waste collection services, she said, the city seems to make every decision with zero-waste in mind. It has even helped launch copycat programs in 26 nearby communities that, altogether, offer more than 300 free zero-waste workshops each year. “Roubaix does things at a level we wouldn’t expect them to do,” Debrabandere told Grist.

Still, she wishes it had the authority to do more.

Some 500 miles south of Roubaix, in a small town called Saint-Denis-de-Pile in the French region of Nouvelle-Aquitaine, Clémentine Derot shimmies into a neon-pink construction vest. She’s about to begin a tour of the headquarters of Smicval, the waste management company that serves 210,000 people across 137 municipalities north of Bordeaux.

Waste reduction is “in our DNA,” Derot says in English, pointing out industrial-sized piles of compost and a warehouse for sorting plastics into bales of recyclable material. There’s also a donation center where residents can drop off toys, dishes, furniture, electronics, and other items they no longer need, and take home other people’s items for free. At one end of the facility, above a chute where dump trucks offload unrecoverable waste, is a massive billboard showing trash building up at the nearby Lapouyade Landfill. “Your trash doesn’t disappear, it’s buried 15 kilometers from here,” the billboard reads, apparently addressing Smicval’s own workers, since the chute isn’t public.

According to Derot, this is all reflective of Smicval’s transformation from a company that simply picks up the trash to a more sophisticated waste prevention and management service, in line with France’s 2021 to 2027 action plan. She describes the status quo waste management model as “totally out of breath” — in need of a complete overhaul — due to escalating concerns over the environment, as well as France’s sharply increasing general tax on polluting activities. In 2019, it cost 18 euros to send a metric ton of waste to the landfill; in 2025, the cost will be 65 euros.

Like Roubaix Zéro Déchet, Smicval envisions a “drastic reduction” in waste generation. But as a regional waste management authority and not a small municipality, Smicval has a very different toolbox at its disposal. Where Roubaix has largely asked residents to opt in to waste reduction, Smicval is able to experiment with more systemic means, like changing the way trash is collected or the way people are charged for disposal services.

The goal, according to Hélène Boisseau, who is overseeing the deployment of Smicval’s new waste management strategies, is to create an environment that is conducive to waste reduction. “We don’t ask for people to become masters in zero-waste,” she said. Rather, “We design the path,” and then guide people along it.

In behavioral science, this is referred to as “contextual change,” where you alter the context in which people make decisions. Instead of merely asking people to do things differently, contextual changes make it easier or more convenient to perform the desired behavior — perhaps by presenting the existing options in a different, more strategic way. Take a middle school lunch line, for example. To get students to eat more vegetables and less pizza, you could either tell them all about the health benefits of broccoli and carrots — or you could move the vegetables to the front of the buffet, so they’re the first things hungry kids see. Many behavioral scientists prefer this type of strategy because it can change lots of people’s behavior all at once — rather than one by one. Plus, it’s better attuned to the unconscious nature of most decision-making.

Smicval’s two biggest strategies revolve around the way waste is collected and how people pay for it. This October, Smicval began a yearslong process of transitioning away from door-to-door waste collection to a model in which people travel to a centralized location, likely within a few blocks’ distance, to drop off their trash. Large bins for trash and recycling — one for every 150 residents — will be openable using a special key card. Community compost bins will be distributed at a rate of one per 80 residents.

According to Boisseau, this model will encourage people to reduce waste simply because it’s inconvenient to haul heavy trash bags down the block. But the longer-term objective is to use those key cards to implement a pay-as-you-throw scheme, in which people pay for waste disposal based on the amount of trash they want to dispose of. Rather than funding Smicval through taxes, families would directly pay the company for different tiers of service, represented by the number of times their key cards will allow them to open the garbage receptacles. The more openings, the more expensive the service, so that people no longer think of waste collection as a limitless public service.

Boisseau compared it to the way people get their electricity bills. Because they can see the charge fluctuating based on their consumption habits, they’ll be incentivized to waste less in order to pay less. “The best way of making sure that people are very concerned with what they put in a bin or a container is to pay for it individually instead of [through] taxes,” she said. Indeed, this principle has been put to use in thousands of towns worldwide, from Berkeley, California, to Austin, Texas, some of whose pay-as-you-throw policies have contributed to municipal solid waste reductions of 50 percent or more. Waste experts say these policies are some of local governments’ “most effective tools for reducing waste.”

Smicval is still sorting out the details of the new system, which is unlikely to be fully adopted until at least 2027 or 2028. In the meantime, Smicval expects to see significant cost savings from fewer and shorter garbage truck routes, which it will use to fund some of its other waste-reduction projects: things like a pilot program for reusable diapers, political advocacy for a bottle deposit bill, a 10,000-signature petition asking grocery stores to eliminate unnecessary plastic packaging, and a Roubaix-esque “zero-waste cities” program, in which Smicval distributes reusable cleaning products and informational pamphlets to the residents of participating municipalities.

Barnett, the behavioral scientist, applauded Smicval for using a broad range of strategies to encourage zero-waste. “They are attacking this from different angles,” she said.

Still, she and the other behavioral scientists Grist spoke with noted the risk of backfire. Although small hassles can be “quite impactful” in catalyzing behavior change, Wright, with Ideas42, said they can also go too far and encourage noncompliance. For something like centralized waste collection or a pay-as-you-throw system, this could mean people dumping their waste illegally or finding a workaround that allows them to open the trash receptacles more often than what they’re paying for. Wright said the program’s success will hinge on specific design considerations, like the way direct invoicing is presented to customers.

If Smicval’s waste-reduction policies are particularly unpopular, Boisseau said it’s even possible that a conservative slate of candidates could be elected to the organization’s board and walk back or weaken its environmental initiatives. Already, Smicval has gained critics who say that centralized waste collection is too onerous. These include the mayor of Libourne, the largest city in Smicval’s territory, who at a meeting last year predicted that the organization’s strategy would turn Libourne into “a trash can,” with people dumping garbage on the streets. If these critics were to mobilize the population against Smicval’s agenda, Boisseau said, “we know they would fight hard.”

A similar problem is unfolding on a national scale, as France prepares to meet a January 1 deadline to equip all of its households with composting receptacles. Observers are afraid that the rollout will be a “nightmare,” and that “a lot of people don’t want to take part.”

Smicval is aware of the obstacles it faces and has been proactive in its efforts to preempt or overcome them. As it slowly transitions to centralized waste collection, for example, the organization is going city by city and saving Libourne for last, hoping that a successful rollout in some of its more supportive municipalities will assuage fears in Libourne. To avoid backlash, it has also consulted with individual citizens to hear their concerns, act on their feedback, and — in some cases — design project proposals to be presented to Smicval’s board.

We try to work with citizens, rather than for them, Derot said. “They know what they need.”

Despite the many overlapping benefits of zero-waste, the movement sometimes gets a bad rap because of its focus on consumers, rather than manufacturers. Why ask individuals to shop in the bulk aisle or pay more for trash disposal if the petrochemical industry is just going to more than triple plastic production by 2050 anyway?

“We are kind of tired of everyone saying it’s on the citizens’ part” to reduce waste, Debrabandere, with Zero Waste France, told Grist. She and other environmental advocates agree there’s an urgent need for waste-reduction policies that are even more aggressive than France’s current ones — for example, mandatory waste sorting in all restaurants, as well as more stringent requirements for the use of post-consumer recycled content and a faster phase-out of single-use plastics.

But the zero-waste policies of advocates’ dreams will require even more intensive behavior shifts than those that Roubaix and Smicval are trying to navigate. For example, imagine a world where France — or any developed country, for that matter — bans products from being sold in disposable containers. This would require people to deal with new enforcement infrastructure at the local level, to shop at new businesses that can accommodate reusable and refillable product systems, and to lug around their own jars and jugs and bottles.

There are many, many other routine habits that consumers will have to dispense with or fundamentally alter in order to create a zero-waste economy, like buying plastic toothpaste tubes and getting takeout in throwaway packaging. The work that Roubaix and Smicval are doing in France is an early part of that process. By figuring out how best to engage their citizens on behavioral change, they are helping to create a smoother path toward the deeper, more radical changes that advocates hope are coming in the near future.

Barnett said there’s also value in the work Roubaix and Smicval are doing to understand zero-waste behavior in their respective regions. Behavioral scientists used to think humans could be characterized by a set of “universal truths,” Barnett said. But that’s less the case now: “We need to go in there and figure out more about the environmental context, the people that are there,” she explained.

Meanwhile, as Roubaix and Smicval continue to try to win over new residents, they both have the benefit of an unusually enthusiastic army of supporters. Nieuwjaer isn’t the only zero-waste devotee who’s all too eager to proselytize about the simple joys of reducing waste. Chloé Audubert, who has spent the past two years working at one of Smicval’s sorting centers, said she loves helping people sort and limit their déchets enfouis — their waste destined for the landfill. And Otimi, the Roubaix resident who leads a family of 10, could barely find the words in English to express what Roubaix Zéro Déchet has meant to her. “This program changed my life,” she finally said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline In France, zero-waste experiments tackle a tough problem: People’s habits on Dec 6, 2023.

For the better part of a decade, researchers working at the intersection of climate change and human health have been desperately sounding alarm bells about the significant public health threats lurking in every tenth of a degree of planetary warming. Billions of people are at risk from illnesses linked to extreme heat; malnutrition following crop failure; bacteria and viruses that lurk in mosquitoes, ticks, and water; and other climate-driven threats.

Yet health has never been on the official agenda at the annual United Nations climate change conference, where leaders representing countries around the globe gather to negotiate climate policy. That changed at this year’s Conference of the Parties, or COP28, which is currently taking place in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Sunday was the first ever COP “Health Day,” designed to bring together health and environment ministers from dozens of countries to discuss the health effects of climate change and brainstorm potential solutions.

“For too long, health has been a footnote in climate discussions,” Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the World Health Organization, said on Sunday. “No more.”

Health researchers and advocates celebrated the milestone, but when Health Day was over and the resulting commitments were tallied, most emphasized that more needs to be done to protect communities from the health impacts of the climate crisis. “We must not lose sight of the actual negotiations happening behind closed doors, especially on the fossil fuel phaseout, which is what will truly slow and stop climate change from worsening,” said Ramon Lorenzo Luis Guinto, director of the planetary and global health program at St. Luke’s Medical Center College of Medicine in the Philippines and a COP28 attendee.

Even before Health Day began, delegates from 123 countries had already signed the COP28 UAE Declaration on Climate and Health, a nonbinding commitment to protect communities by investing in climate adaptation measures and making health systems more resilient to climate impacts.

The declaration has some significant funding behind it: A coalition of philanthropies and aid organizations, such as the Rockefeller Foundation and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria, collectively pledged $1 billion in new funding to address the climate health crisis. A COP28 spokesperson told Grist that the funding had all been pledged recently — either in the lead-up to the conference or during the event. For instance, the $100 million contributed by the Rockefeller Foundation was announced in September as part of the philanthropy’s five-year “climate strategy,” a Rockefeller spokesperson said.

“Climate change is increasingly impacting the health and well-being of our communities,” said President Lazarus Chakwera of Malawi, one of the initial backers of the declaration. “Extreme weather events have displaced tens of thousands of our citizens and sparked infectious disease outbreaks that have killed thousands more.”

More than 40 banks, governments, and other organizations also signed on to a set of 10 broad principles aimed at guiding international financing for climate and health infrastructure, local projects, and solutions. The principles include supporting the climate and health priorities of countries most affected by climate change and simplifying the processes for accessing available climate and health funds.

On Health Day, global donors including UAE President Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation pledged nearly $800 million to eradicate neglected tropical diseases — a group of 20 climate-sensitive illnesses that affect 1.6 billion of the world’s poorest people, the majority of whom are already extremely vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

In addition to these landmark pledges, Health Day at COP28 included dozens of health-focused events that took place in an official health pavilion, as well as in other pavilions and tents across the conference. Kristie L. Ebi, a climate and health researcher at the University of Washington who has attended every COP since 1997, called the day a “watershed moment” for her field. “Most of us spent our day going from one pavilion to another to talk about climate change and health,” she said. “The visibility overall of climate change and health dramatically shifted with this COP.”

As prior COPs have shown, making climate commitments is often the easy part — actually seeing them through is much harder. Jeni Miller, executive director of the Global Climate and Health Alliance, said the Declaration on Climate and Health was welcome but cautioned against assuming that the declaration will lead to material benefits for affected populations. “It contains no plans for action right now, and does not have clear goals or targets,” she said. “Nor does it mention the extraction and burning of fossil fuels as the leading cause of climate change and climate-related health threats.” The $1 billion pledge, she added, also does not contain language that describes how developing countries can secure funds for local climate and health projects. How that money will be distributed or used remains to be seen.

Speaking at an event on Health Day, Maria Neira, director of the Public Health, Environment and Social Determinants of Health Department of the World Health Organization, put it succinctly: “This is quite historic,” she said, “but it is just the first day of history.”

More history could be made at COP28. Negotiators are currently debating “an orderly and just phaseout of fossil fuels,” which, if it is adopted, would be the first international deal on the books to call for an end to fossil fuel use. But progress is extremely tenuous — striking a deal on any climate proposal requires unanimous consent from all participating countries. It takes just one dissenting nation to scramble a negotiation, and Saudi Arabia’s energy minister said on Monday that he will not agree to “phaseout” or “phasedown” fossil fuels. Saudi Arabia’s commitment to fossil fuels does not make it an outlier at the conference. Recent reporting revealed the president of COP28, Sultan Al-Jaber, has falsely claimed there is “no science” backing up the idea that eliminating fossil fuels is key to keeping global warming in check.

Still, mitigating climate change is just one part of the challenge the world faces. For the world’s developing countries, which contribute a very small amount to the world’s carbon budget, adapting to the consequences of rising temperatures is now more important than mitigating its effects. That’s why the pledges made at Health Day are significant, Ebi said. Preparing these countries for the health-related climate impacts to come is “fundamental to their national development,” she said. At COP28, the preparations finally got underway.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline At COP28, world leaders turn a belated spotlight on human health on Dec 6, 2023.

Most Americans would prefer to live in a home where almost all major appliances run on electricity — but only if they can keep their gas stoves. Just 31 percent want to go fully electric.

Researchers asked roughly 1,000 people to what extent they would prefer to have their appliances powered by electrons or fossil fuels (natural gas, propane, or oil). It was the first time such a question was included in the long-running Climate Change in the American Mind survey, conducted by Yale and George Mason universities. The surveys, which started in 2008, are conducted biannually to track attitudes toward climate-related issues, such as electrification.

“We realized we didn’t really have a baseline for what people actually want,” said Jennifer Marlon, a research scientist at the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication who helped design the question and push for its inclusion. Combine those who said they would go fully electric with the 29 percent who would do so except for their gas stove, and 6 in 10 Americans are ready to decarbonize. ”As a starting point, this is quite encouraging.”

Addressing residential energy use is critical to combating climate change, as the sector accounts for 20 percent of greenhouse gas emissions in the United States. Meeting the 2050 goals of the Paris Agreement will require an aggressive move to decarbonize the grid and move homes off of oil and natural gas onto efficient electric options such as heat pumps.

While the United States boasts one of the lowest rates of support for climate policies in the world, this polling question suggests many Americans are open to a more electric future. That said, the appetite for eschewing fossil fuels varies by political affiliation. Three-quarters of liberal Democrats, for instance, would prefer an all or mostly electrified home, while that number sits at half for conservative Republicans.

However, people across the political and demographic spectrum are very attached to their natural gas stoves — an affinity that was particularly strong among respondents who identified as Hispanic. Nationally, one-third of all homes use methane for cooking and when the Consumer Product Safety Commission said it might take steps to regulate gas stoves, it sparked a culture war. While that stickiness is perhaps evidence of industry efforts, dating to the 1970s, to promote the devices, the reality is they represent a small portion of residential energy consumption.

“If people did one thing in the home that really mattered, it would be to get rid of their gas [or oil] furnaces,” said Rob Jackson, a Stanford University professor who has researched methane extensively. But, he added, there are clear health reasons for cooking with electricity.

“Gas stoves emit pollutants like nitrogen dioxide and benzene into the air we breathe,” he said, and nearly 13 percent of childhood asthma cases in the U.S. have been linked to the devices.

Beyond the gas stove caveat, there are other reasons to be cautious about the polling results, said Sanya Carley, an energy policy researcher at University of Pennsylvania. She says the framing of the question may have led to results that are particularly favorable to electrification. For example, using the term “fossil fuel” in contrast to “electricity” could prime people to choose electricity.

“People have far more extreme views when you’re talking about fossil fuels than they do when you’re talking about anything else,” she said, also noting that electricity is frequently generated by burning coal or natural gas. “I think it is either confusing to some people or misleading.”

The survey also told respondents to assume “costs and other features are the same.” That’s a big assumption, because the price and performance of gas, oil, propane and electric systems can vary widely. The cost of heat pumps, for instance, depends on state and local rebates, and homes in cold weather climates may still require backup sources of heating.

The language of the question was heavily vetted, said Marlon, and had to fit a national audience. Its aim was to elicit what people truly want in a way that allows comparison across various geographies and demographics. She also acknowledged that there is likely a gap between someone preferring an electrified home and someone actually taking steps to make that happen.

But, she said, arguably the most important part of the poll is that it sets a baseline that future polling can be compared to. The plan is to continue asking the question at least annually and ideally add in other more specific queries as well.

“There are a lot of questions we’d like to ask,” said Marlon. “We squeezed in this one question to get started.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Most Americans want to electrify their homes — if they can keep their gas stoves on Dec 6, 2023.