We need wilderness, author Edward Abbey explained, whether we set foot in it or not….

The post Earth911 Inspiration: We Need Wilderness appeared first on Earth911.

We need wilderness, author Edward Abbey explained, whether we set foot in it or not….

The post Earth911 Inspiration: We Need Wilderness appeared first on Earth911.

For the past year and a half, you may have heard a lot about butter. It started with a viral video of influencer chef Justine Doiron carefully slathering two sticks of butter directly onto a wooden cheese board, seasoning the thick layer with flaky sea salt and lemon zest, arranging torn herbs and red onion across the surface, and finally finishing the dish with flower petals and a drizzle of honey. This was the butter board, a TikTok trend that quickly reached escape velocity and was featured by The New York Times, CNN, and the Today Show.

On high-end restaurant menus, the once-humble bread-and-butter course snowballed into $38 tableside “butter service,” and 14-inch cylinders of creamy, imported carved-to-order butter earned prominent placement in restaurants’ open kitchens. By early March, New York Magazine could declare that “butter has become the main character.”

What accounts for butter’s spectacular renaissance in American cuisine? According to the U.S. dairy industry, it’s their own public relations campaign that started the spread. The industry marketing group Dairy Management Inc., has claimed credit for the butter board in industry press, because it paid Doiron as a sponsor at the time of her video. While Doiron’s original butter board video did not include an advertising disclosure — and, according to Dairy Management, was not itself technically part of the partnership — the chef posted a Dairy Management ad two days before her viral post and was part of the industry group’s “Dairy Dream Team” of paid influencers at the time. (Doiron did not respond to an interview request, but Dairy Management told Grist that her contract has since expired.)

Dairy Management, whose funding largely consists of legally mandated fees collected from farmers, is one of a constellation of government-supported dairy marketing groups that also includes the Fluid Milk Board, a beverage-focused entity whose promotion arm has paid Emily Ratajkowski, Kelly Ripa, Amanda Gorman, and more than 200 others to promote milk on social media. (The milk board also recently sponsored a section in New York Magazine’s The Cut, focused on women in sports.) In recent years, Dairy Management has partnered with mega-influencer MrBeast at least twice, filming him as he toured a dairy farm and paying him to promote a dairy-focused competition in the video game Minecraft.

In perhaps dairy promoters’ biggest coup of last year, the limited-run McDonald’s Grimace shake went viral after TikTok users began crafting miniature horror films featuring the bright purple beverage. Dairy Management has a longstanding partnership with McDonald’s; beginning in 2009, it placed two dairy scientists at the fast food chain to help incorporate more dairy into the menu. Less than a decade later, 4 in 5 McDonald’s menu items contained dairy, according to a Dairy Management board member. Dairy Management has even funded research to help improve McDonald’s notoriously glitchy milkshake machines.

“My hope is that farmers, when they see a new milkshake or a new McFlurry at McDonald’s, that they know that it’s their new product,” Dairy Management CEO Barb O’Brien said on a podcast in December.

A spokesperson for McDonald’s told Grist that they could not independently confirm the proportion of their offerings that contain dairy due to variations in local menus, but added that the fast food chain makes its own menu decisions. “Our partnership with [Dairy Management] helps McDonald’s ensure the quality and great taste of the dairy-based items on our menu, and deepen relationships with the thousands of dairy farmers who supply milk, cream, butter, and cheese to restaurants across the U.S.,” the company said in an emailed statement to Grist.

Partnering with food companies to roll out products that contain ever-escalating quantities of dairy is one of the industry group’s tried-and-true strategies. In the last couple of years, Dairy Management has partnered with Taco Bell to launch a frozen drink mixing dairy with Mountain Dew and a burrito with ten times the cheese of a typical taco. The organization also assisted with last year’s rollout of pepperoni-stuffed cheesy bread at Domino’s and supported marketing efforts for General Mills’ Oui line of yogurts.

Thirty years after the era-defining “Got Milk?” campaign — itself a project of the California Milk Processor Board — the U.S. dairy industry’s PR machine appears to be getting a second wind. The point of all these efforts is straightforward: The dairy promotion boards’ mission is to increase demand for their products. They spend hundreds of millions of dollars, collected from farmers and milk processors, on annual research and advertising in hopes of growing the market for dairy domestically and abroad.

However, as dairy consumption and production continue to grow, so too does the industry’s environmental footprint. In 2019, the EPA estimated that U.S. dairy cattle emitted 1,729,000 tons of methane each year, pollution roughly equivalent to 11.5 million gasoline-powered cars being driven over the same period. A United Nations report found that the dairy sector’s global greenhouse gas emissions rose by 18 percent between 2005 and 2015.

Meanwhile, it’s not entirely clear that all these efforts are helping the average dairy farmer. The number of U.S. dairy farms has fallen by three quarters in the last 30 years, as farmers’ costs rise and milk prices fluctuate. Many small and mid-sized dairy farms have been driven out of business and farmers’ net returns fall below zero year after year. In 2000, farms with more than 2,000 cattle produced less than 10 percent of milk, but by 2016 farms of this size were responsible for more than 30 percent of U.S. production. The diverging trend lines have prompted some farmers to question whether the focus on market growth above all else — which has been accompanied by increasing climate pollution and the collapse of small dairy herds — is still the best policy.

Ever since Congress passed the Dairy Act in the 1980s, farmers have been required to pay 15 cents per hundred-weight of milk (equivalent to a little less than 12 gallons) toward industry promotion programs overseen by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, or USDA. Ten cents is sent to local promotion entities and the remaining five cents go to the national Dairy Board, which promotes all dairy products. (Eggs have their own $20 million program.) Farmer contributions to the national program totaled $124.5 million in 2021.

The Dairy Board in turn sends money to Dairy Management Inc. Milk processors work under a similar structure, paying their own assessments to the Fluid Milk Board, which works exclusively on promoting a category that includes milk, flavored milk, buttermilk, and eggnog. The Fluid Milk Board received $82.4 million in processor fees in 2021. Its marketing arm is called MilkPEP.

In an emailed statement, a Dairy Management spokesperson told Grist that “all dairy research, promotion content and information not only complies with all regulations and standards, but also seeks to help consumers make informed decisions about the foods they choose for themselves and their families, including nutritious, sustainably produced dairy.”

The financial structure of these efforts is complicated, but the end result is that these programs, which are known to farmers as “checkoffs,” bring in more than $200 million each year in the dairy industry alone. As a result, the industry takes care to note its accomplishments. For instance, in the first eight years the checkoff of partnered with Domino’s Pizza, the average store increased its cheese use by 43 percent.

Other promotional efforts, however, have amounted to slickly-produced flops. Last year, the Fluid Milk Board hired actor Aubrey Plaza to hawk “wood milk” in an apparent effort to lampoon plant-based milk alternatives, which resulted in a formal complaint filed by a group of physicians who advocate for plant-based diets. Another effort involved a Board-funded website featuring Queen Latifah, which was devoted to combating the seemingly fictional phenomenon of “milk shaming.”

Some recent industry-funded persuasion campaigns have been more subtle. In 2021, the fluid milk checkoff sponsored a wellness weekend for top editors from Bustle, New York Magazine, Marie Claire, and others at a $750-per-night Hamptons resort where they participated in workouts led by a celebrity trainer and “partook in milk-forward meals.” Congressional disclosures indicate that the Fluid Milk Board held USDA-approved advertising and marketing contracts with Vice Media and Food52 in 2021. A spokesperson for MilkPEP told Grist that these were branded editorial contracts to develop milk-inclusive recipe content.

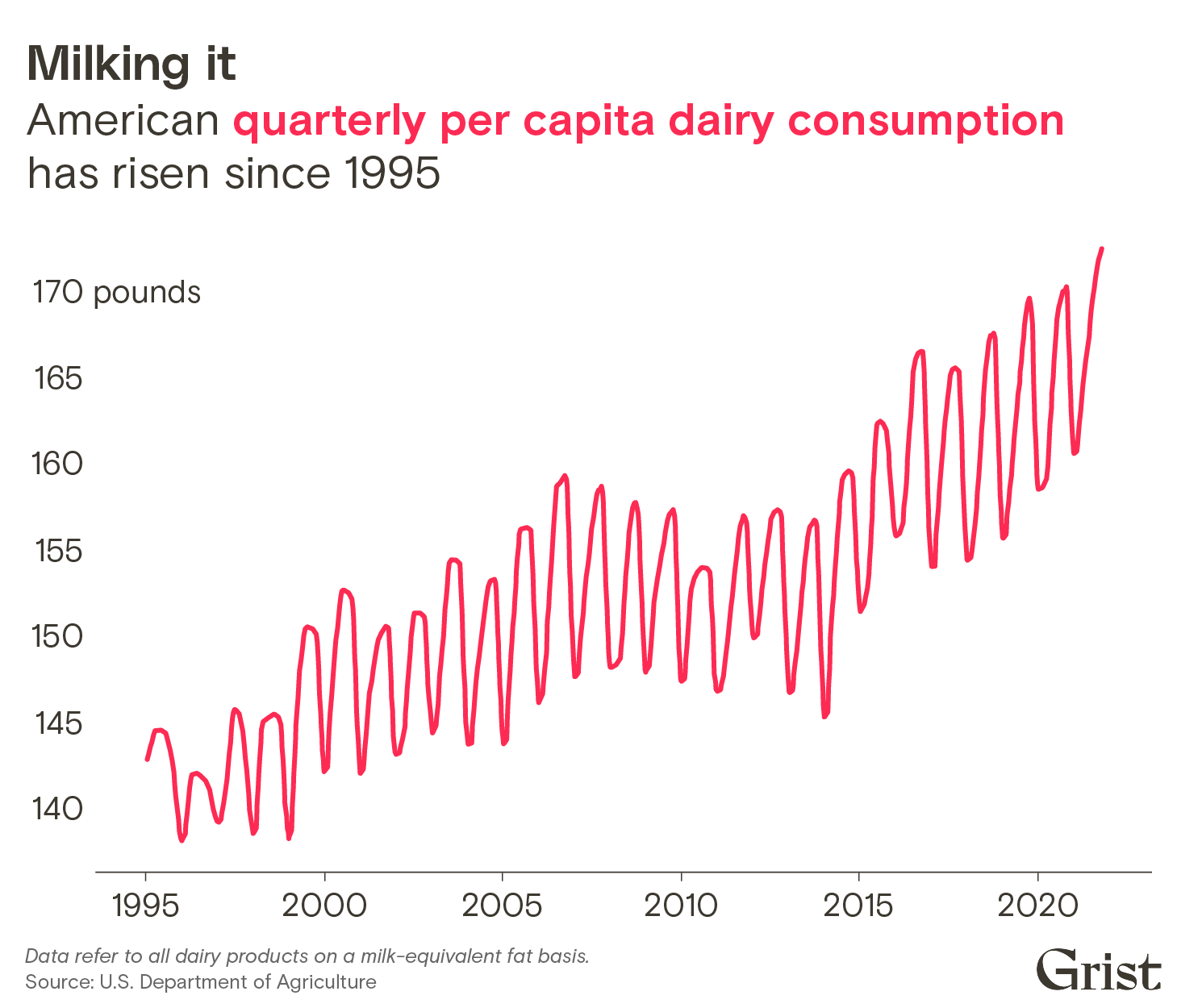

There’s some evidence that all this marketing has worked. A recent USDA report delivered to Congress claimed that farmers earn $1.91 for every dollar spent on “demand-enhancing activities” for fluid milk, $3.27 for every dollar spent promoting cheese, and $24.11 for every dollar spent boosting butter. An independent evaluation by the Government Accountability Office in 2017 likewise found that, between 1995 and 2012, the fluid milk program returned $2.14 for every dollar spent.

After decades of growth, per-capita U.S. dairy consumption reached an all-time high in 2021, though fluid milk consumption has been steadily declining since the 1970s. This presents formidable challenges for climate action: Meat and dairy consumption is responsible for a full 75 percent of the country’s diet-related greenhouse gas emissions, even though animal products account for only 18 percent of calories consumed.

And even setting aside climate concerns, small-scale farmers worry that this emphasis on demand growth might actually end up edging them out of the market. They say that the checkoffs have unfairly benefited a few big producers, supercharging their growth while driving others out of the industry.

“[The checkoff is] set up to be entirely demand-side,” said Wisconsin farmer and former Dairy Board member Rose Lloyd. “You’re not allowed to talk about price, you’re not allowed to talk about supply. It’s a wasted effort.”

Lloyd and her family maintain a herd of 350 cows, and while checkoff assessments represent less than 1 percent of her revenue, she says she feels like she’s paying to reinforce a structure that’s working against her farm and her community. For example, she’s watched a neighboring dairy farm quadruple in size to supply mozzarella to a nearby factory that produces frozen pizzas. The local infrastructure has struggled to contend with the waste produced by all those additional cows.

“We have massive water quality issues,” she told Grist. “It’s a real crisis right now on all the legs of sustainability: ecologically, socially, economically.”

Some farm groups are holding out hope that they can persuade Congress to pass a form of supply-management legislation that limits total milk production, which they are pitching as a win-win for small-scale farmers and the environment. If the government placed a cap on the amount of dairy produced in the United States, the idea goes, such a policy could theoretically ensure that a market exists for all the dairy produced.

A similar model has functioned in Canada for decades. Each year, annual dairy demand is forecasted based on the previous year’s sales figures. The resulting estimate is divided among provincial boards, which in turn distribute production quotas to individual farmers. In exchange for promising not to market more milk than the quotas allow, farmers are guaranteed minimum prices for their products — meaning they’re somewhat insulated from the seasonal price fluctuations and rising costs that plague their U.S. counterparts.

To maintain this delicate balance, Canada prevents an influx of cheap imported milk using high tariffs. In part for this reason, the system is not without controversy. Critics argue that the policy pushes up dairy prices, and the quota licensing system can make it hard for new producers to enter the market.

Still, the system has enough admirers that some are hoping it will be adopted in the U.S. Earlier this year, representatives from the National Family Farmers Coalition, or NFFC, flew to Washington, D.C., to try to persuade legislators to adopt supply-management legislation through their proposed “Milk from Family Dairies Act” in the next Farm Bill. The bill would establish price minimums and quota-like “production bases” for farmers. Farmers would have to pay additional fees to export their product, and the policy would raise import fees where possible.

Antonio Tovar, senior policy associate at NFFC, said the proposal has garnered support from environmental groups who see supply management as a means of reducing emissions from feed and trucking.

Nevertheless, Tovar is clear-eyed about the bill’s likelihood of passage, at least in the near term. “I have to be honest with you, I’m a little bit pessimistic about these proposals being included in the next Farm Bill,” he said, citing Congressional gridlock and limited political will to pursue the change.

In the meantime, the dairy checkoff has set its sights on the export market. Specifically, it’s promoting pizza — which one executive called “a strong carrier for U.S. cheese” — in the Middle East and Asia. In Japan, the checkoff and Domino’s launched a “New Yorker” pizza topped with a full kilogram of cheese and served with a packet of seaweed and maple syrup. The New Yorker was subsequently rolled out in Taiwan.

Domestically, there are still some fast-food menu items that haven’t yet been topped with a slice of American cheese or shaken with milk. In a 2022 blog post, Dairy Management Inc., chair Marilyn Hershey pointed out that 80 percent of the 2 billion chicken sandwiches sold in the U.S. each year do not contain a slice of cheese.

The checkoff, she wrote, was engaging with Chick-fil-A, Raising Cane’s, and McDonald’s to change that.

Correction: This story has been corrected to remove language suggesting that dairy promotional groups engage in political lobbying.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Behind the ‘butter board’: How the dairy industry took over your feed on May 10, 2024.

As a series of monster rainstorms lashed southeast Texas last week, thousands of homes flooded in low-lying neighborhoods around Houston. The storms dropped multiple months’ worth of rainfall on Houston in the span of a few days, overtopping rivers and creeks that wind through the city and forcing officials to divert millions of gallons of water from reservoirs. Elsewhere in the state, the rain and winds killed at least three people, including a 4-year-old boy who was swept away by flooding water.

Much of the deepest flooding happened in the San Jacinto River, a serpentine waterway that winds along Houston’s eastern edge and empties into the Gulf of Mexico. This area happens to be the site of perhaps the country’s longest-running experiment in the adaptation policy known as “managed retreat,” which involves moving homeowners away from neighborhoods that will become increasingly vulnerable to disaster as climate change worsens. Harris County has spent millions of dollars buying out and demolishing at-risk homes along the river over the past decade. But the past week’s flooding has demonstrated that even this nation-leading program hasn’t been able to keep pace with escalating disaster.

“This is basically the largest and the deepest river within the county, and the floodplain is so deep that really we can’t do projects to fix these areas,” said James Wade, who leads the home buyouts for the Harris County Flood Control District. “We’re trying to get contiguous ownership in these areas so that we can basically convert it back to nature.”

It’s been slow going: Wade says the county has purchased about 600 flood-prone homes along the waterway over the past 30 years, almost all of which would have flooded during the recent storm if they hadn’t been bought out and demolished. There are still more than 1,600 vulnerable homes that the county is trying to purchase, but it has struggled to secure the necessary funds and get property owners on board.

Harris County was one of the first local governments in the United States to buy out flood-prone homes with money provided by FEMA, the federal disaster relief agency. The county has acquired more than 4,000 homes in dozens of subdivisions around Houston since the turn of the century, creating what are essentially miniature ghost towns around the city and its suburbs. Many of these neighborhoods, including the ones around San Jacinto, were so prone to flooding that the county couldn’t protect them with channels and retention ponds, which secure other residential areas.

The county doubled down on this strategy around the San Jacinto after Hurricane Harvey flooded hundreds of homes along the river in 2017, confirming that many residences were “hopelessly deep” in the floodplain, in the county’s words. Not only is the land around the river low-lying and marshy, but it also sits downstream of a reservoir that needs to release water during flood events so it does not overflow.

The county used federal funds to purchase and demolish an entire subdivision called Forest Cove, converting the open space into a “greenway” park with walking and bike trails. Elsewhere, it bought out homeowners who had already elevated their riverside homes as high as 14 feet in the air but had still seen flooding during Hurricane Harvey. These buyouts were voluntary, but after years of advocacy the county managed to persuade most homeowners to leave.

A separate county agency pursued a mandatory buyout in a few subdivisions where residents had been flooded several times, including one large community along the San Jacinto. This mandatory initiative has drawn criticism from residents who accuse the county of uprooting established communities, but the county saw it as a necessary measure to control flood risk in places where no other flood control strategies would work. More than six years after Harvey, officials are still working to close on the last of those homes.

Yet this aggressive program has still left many vulnerable neighborhoods untouched. The county gets most of its buyout funding from FEMA and the Department of Housing and Urban Development, which tend to dole out grants only after big disasters. It has also floated a $2.5 billion bond to finance flood protection and buyouts, but that sum has proven too little. There are far more flood-prone homes even along the San Jacinto than the county can afford to buy, to say nothing of the rest of the Houston metropolitan area, one of the country’s most populous urban centers.

“Money is obviously the biggest constraint,” said Alex Greer, an associate professor of emergency management at the University at Albany who has studied buyout programs. “They often have far more interested homeowners than they have funds, and the funding comes way too late.” Wade isn’t sure yet whether the flood caused enough damage to meet the criteria for a presidential disaster declaration, which would unlock significant FEMA aid and likely help the county fund more buyouts along the San Jacinto.

Furthermore, buyouts can take years to execute. In most cases, the county has to convince individual homeowners to enroll in a buyout program, then complete months of paperwork to purchase their homes, then wait for the homeowners to move. If there are holdouts who don’t want to leave, the buyouts end up happening in a “checkerboard” pattern, and the government can’t let water retake the land. Some neighborhoods, like those in the more upscale Kingwood area, are fighting for alternate solutions like new upstream reservoirs or dredging projects that could reduce flooding without homeowners needing to leave.

Even though residents along the beleaguered river have been dealing with floods for decades, Wade says he hopes this most recent flood will convince more of them to join the buyout program, allowing the county to return more land along the river back to nature. Without more money, though, he won’t be able to take advantage of what Greer calls the “window to woo.”

“Right after a flood event, that’s when people are most like, ‘I don’t want to do this again,’” he said. “But then there’s that lag of time between them coming forward and us being able to secure the funds, and they could change their minds.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Texas flooding brings new urgency to Houston home buyout program on May 10, 2024.

Scientists have discovered that the highly intelligent and social chimpanzee continues learning and honing the use of tools well into adulthood. This ability could be vital for the evolution of complicated and varied tool use.

In the study, the researchers said tool use is rare in animals, but they discovered that chimpanzees employed hand grips utilizing more than one finger as they got older.

“Such hand grips emerged at the age of 2, became predominant and fully functional at the age of 6, and ubiquitous at the age of 15, enhancing task accuracy. Adults adjusted their hand grip based on the specific task at hand, favoring power grips for pounding actions and intermediate grips that combine power and precision, for others,” the study’s authors wrote. “Highly protracted development of suitable actions to acquire hidden (i.e., larvae) compared to non-hidden (i.e., nut kernel) food was evident, with adult skill levels achieved only after 15 years, suggesting a pronounced cognitive learning component to task success.”

Humans have the ability to keep learning throughout their lives, and it is thought that this is why they are able to use tools with such flexibility. This ability has been an essential part of the evolution of human culture and cognition, a press release from the Public Library of Science (PLOS) said.

The research team examined whether chimpanzees also have this ability by looking at how their tool techniques evolved with age. They recorded 70 chimps of various ages retrieving food with sticks over the course of several years in the wild at Côte d’Ivoire’s Taï National Park.

The chimpanzees became more skilled at using suitable finger grips in handling the sticks as they got older and continued honing their gripping techniques well into adulthood.

Some more advanced skills like using sticks to pull insects out of places that were difficult to reach or adjusting their grip for different tasks were not completely developed until the age of 15. This suggests the more complex skills are not only a matter of physical maturity, but a product of learning capacities for novel technological methods that progress as they age.

The team found that retention of learning capacity as adults seems to be a useful attribute for species that use tools — an important insight into chimpanzee and human evolution. The authors noted that additional study would be necessary to fully understand the learning process of chimpanzees, such as how memory and reasoning play a role and how important experience is in comparison to instruction from peers.

“In wild chimpanzees, the intricacies of tool use learning continue into adulthood. This pattern supports ideas that large brains across hominids allow continued learning through the first two decades of life,” the authors said in the press release.

The study, “Protracted development of stick tool use skills extends into adulthood in wild western chimpanzees,” by Mathieu Malherbe and colleagues from France’s Institute of Cognitive Sciences, was published in the journal PLOS Biology.

The post Chimpanzees Improve Tool-Using Skills Into Adulthood, Study Finds appeared first on EcoWatch.

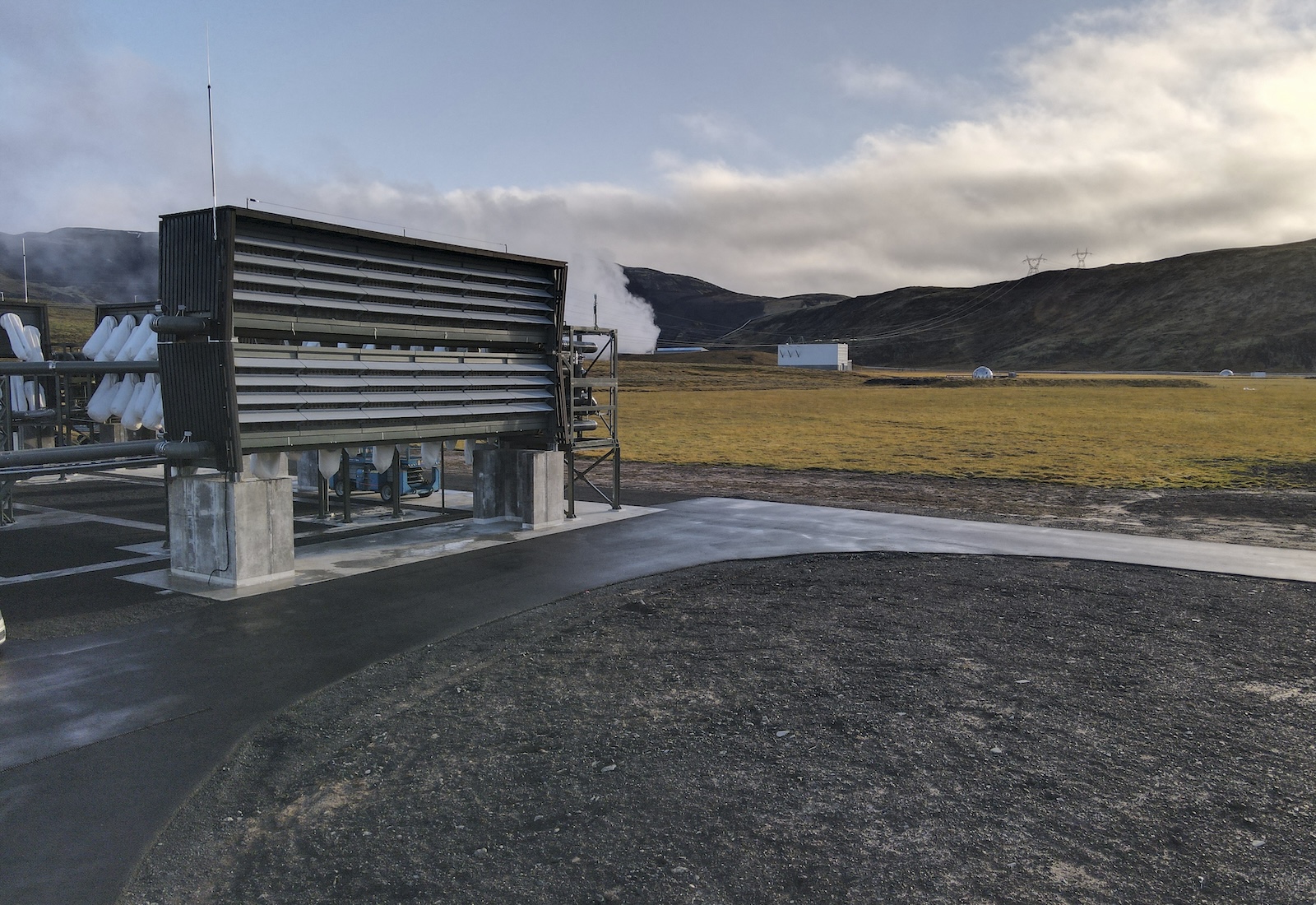

Swiss company Climeworks has opened the biggest operational direct air capture (DAC) plant in the world to pull carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

The Mammoth plant, located in Iceland, is nearly ten times bigger than Orca, its second-largest plant.

“Starting operations of our Mammoth plant is another proof point in Climeworks’ scale-up journey to megaton capacity by 2030 and gigaton by 2050,” said Jan Wurzbacher, Climeworks co-founder and co-CEO, in a press release from Climeworks.

The DAC process sucks carbon from the air and stores it, most often underground, where it can no longer contribute to global heating.

With global efforts to reduce fossil fuel emissions inadequate to prevent the worsening effects of climate change, United Nations scientists have estimated that carbon dioxide in the billions of tons will need to be removed to meet climate targets, reported Reuters.

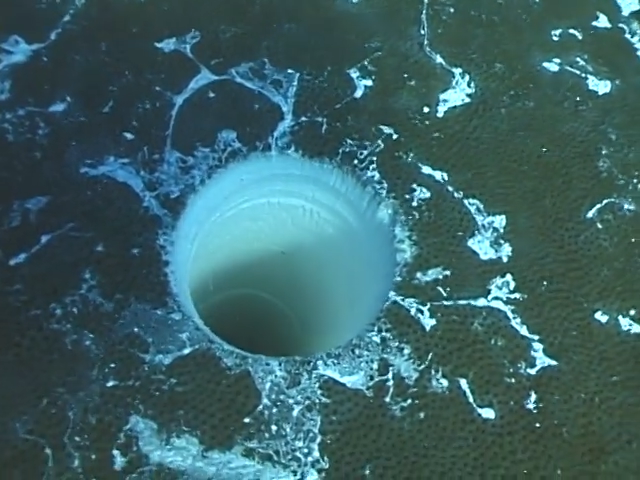

Climeworks’ new DAC plant has an annual carbon capture capacity of 36,000 metric tons. The Mammoth plant, begun in 2022, will be completed by the end of this year.

The company’s first commercial DAC project was also in Iceland — the Orca plant — and has an annual capacity of 4,000 metric tons.

“Mammoth has successfully started to capture its first CO₂. Climeworks uses renewable energy to power its direct air capture process, which requires low-temperature heat like boiling water. The geothermal energy partner ON Power in Iceland provides the energy necessary for this process,” Climeworks said. “Once the CO₂ is released from the filters, storage partner Carbfix transports the CO₂ underground, where it reacts with basaltic rock through a natural process, which transforms into stone, and remains permanently stored.”

Critics of carbon capture technology argue that it uses an enormous amount of energy, is expensive and that focusing on the removal of carbon from the atmosphere could encourage companies to continue burning fossil fuels rather than lowering their emissions. Many critics also emphasize that its effectiveness has not been proven.

Speaking about carbon capture in general, Lili Fuhr, Center for International Environmental Law’s fossil economy program director, said the technology “is fraught with uncertainties and ecological risks,” as CNN reported.

The total carbon removal capacity on Earth can only remove roughly 0.01 million metric tons per year of the 70 million tons that would need to be removed by the end of the decade to meet worldwide climate goals, the International Energy Agency said.

Climeworks — which does not have ties to fossil fuel companies — said it is looking to lower the costs of DAC technology to $400 to $600 per ton by the end of the decade and $200 to $350 a ton by 2040, reported Reuters.

Development is currently in the works for megaton Climeworks hubs in the United States, the press release said.

The post World’s Largest CO2 Removal Plant Opens in Iceland appeared first on EcoWatch.

Vermont’s House of Representatives has passed S.259, a state bill aimed at collecting recovery costs for climate-related damages from the biggest emitters, such as fossil fuel companies.

The bill, called the Climate Superfund Act, was introduced to create a Climate Superfund Cost Recovery Program, in which fossil fuel businesses would undergo an assessment to determine their share of costs for fossil fuel extraction or refinement actions that led to increased greenhouse gases and related costs in the state.

As reported by NBC News, the agency would measure extreme weather linked to climate change in the state and the cost of damages from extreme weather events through attribution science. From there, the agency would calculate companies’ emissions from 1995 to 2024 to determine a share of the costs to charge each company.

According to the bill, costs collected from the program would be put into a Climate Superfund Cost Recovery Program Fund, managed by the state’s Agency of Natural Resources, with funds going toward state projects that improve adaption or resilience to climate change.

“We’re able to say very clearly, ‘We would not be experiencing these intense global temperatures without human-caused climate change and the history of carbon pollution,’” Andrew Pershing, vice president for science at the nonprofit Climate Central, told NBC News.

“New England has had a 60% increase in the heaviest precipitation days,” Pershing added. “For every 1-degree Fahrenheit increase in temperature, you get a 4% increase in the amount of water vapor that the atmosphere can hold.”

The bill still needs to go through a final approval vote in the state Senate before going to the governor for signing. If it does pass, Vermont would be the first state with a law that holds companies with high emissions financially responsible for climate-related damages to the state. Other states, including New York, Massachusetts, California and Maryland are working toward passing similar legislation.

But the bill could face further hurdles to becoming a law. As The Guardian reported, Republican Governor Phil Scott could potentially veto the bill, but supporters believe they would have enough votes to overturn a veto, if it happens. Even without a veto, the law could face many battles in court from companies that oppose it.

Still, the bill’s supporters believe in fighting for the bill, pointing to strong attribution science that links human activities to climate change and its consequences.

“You see towns across the state underwater, and communities and businesses financially devastated. The reality of the climate crisis just really comes crashing home,” Ben Edgerly Walsh, climate and energy program director for the Vermont Public Interest Research Group, told NBC News. “These are facts that we are dealing with in real time that we need the financial resources to deal with.”

Vermont just experienced its warmest winter on record, Burlington Free Press reported. Last summer, the state broke more records in rainfall and flooding, which cost the Northeast an estimated $2.2 billion.

The post Vermont Could Become First State to Make Biggest Emitters Pay for Climate-Related Damages appeared first on EcoWatch.

Ditch the ordinary, embrace the extraordinary! Made with live-edge, natural wood and cradling delicate plants…

The post How To Make Elegant DIY Test Tube Vases With Live Edge Stands appeared first on Earth911.

Residential recycling is vital to a greener life, but let’s talk about how to recycle…

The post Guest Opinion: Sidewalk Recycling Matters appeared first on Earth911.

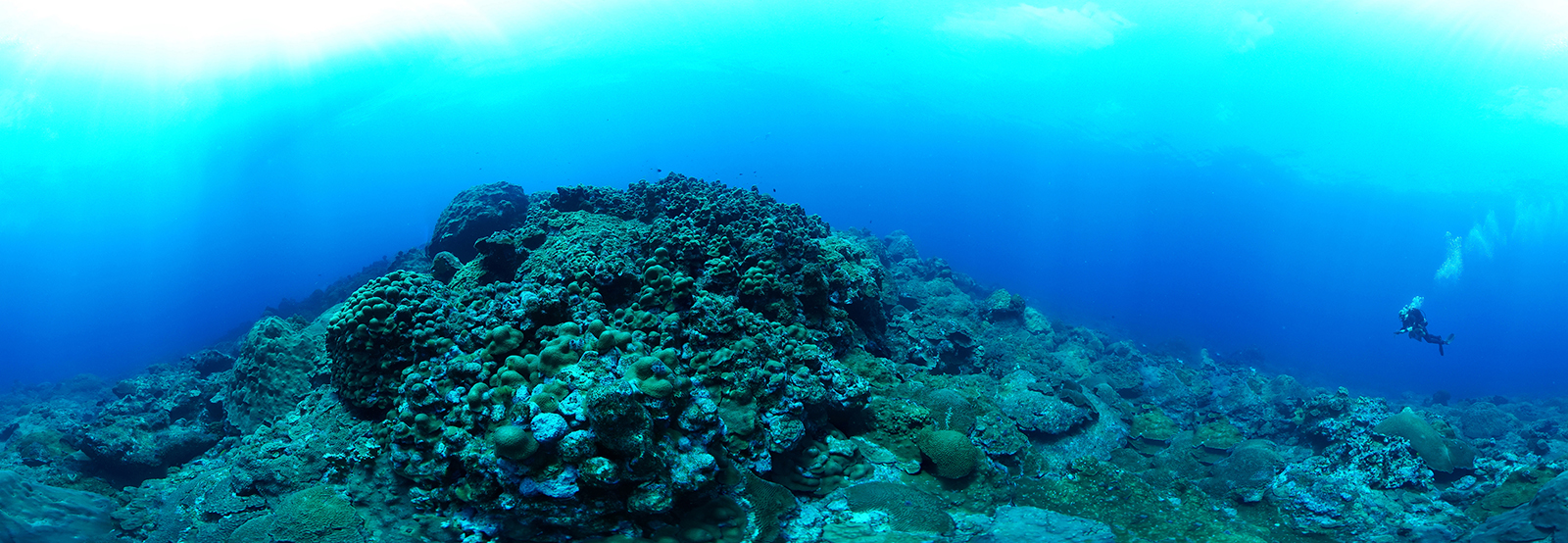

While the Gulf of Mexico is a region known for oil, it’s also home to something far less expected. Nestled among offshore oil platforms, about 150 miles from Houston, is one of the healthiest coral reefs in the world: the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary.

Marine researchers who have visited the Flower Garden Banks describe it with awe in their voices. “When you look out, it can be almost disorienting because there’s so much coral,” said Michelle Johnston, superintendent of the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary.

As reefs around the world bleach at alarming rates, scientists are racing to study and preserve this remarkable coral reef in the unlikeliest of places. “We have these magical underwater places, [and yet they are] completely surrounded by the oil and gas industry,” Johnston said.

To understand how both can exist in such close proximity, it helps to understand the history of the region. Roughly 190 million years ago, the ocean here was drying up, leaving behind a massive plain of salt. Over the ages, that dried-up layer of salt was buried deep in the earth.

And eventually, a new body of water — the Gulf of Mexico — formed high above it. Because salt is less dense than the surrounding rock, the layer slowly rose toward the surface, pushing the earth above it, while pulling up massive oil deposits from below. Slowly, this shift created enormous underwater mountains known as “salt domes.” Looking at a map of the Gulf of Mexico today, you can see that many of its oil drilling sites are on those same underwater mountains.

A few of these mountains rose so high that sunlight was just able to filter down through the water to reach them. And roughly 10,000 years ago, coral polyps latched onto the peaks and started to grow. Those underwater mountaintops are now the Flower Garden Banks.

Because the reef is so far from the shore, it’s been protected from many threats like overfishing and coastal pollution. And because of its depth and northern latitude, the water here is about as cold as corals can tolerate, essentially protecting the Flower Garden Banks from global warming. In the summer of 2023, for example, while other reefs throughout the Caribbean were being ravaged by heat stress and bleaching, the unique geology of Flower Gardens allowed it to fare better than the rest.

But this same unique geology has also turned the region into a massive hub for offshore oil drilling.

“When you’re offshore diving at the Flower Gardens, you look around from the dive boat and you can see oil and gas platforms in every direction,” Johnston said. “So there’s all of this industry happening around this beautiful place.”

For now, the reef has thankfully avoided any catastrophic oil spills, but that doesn’t mean that oil hasn’t left its mark. In fact, the legacy of oil extraction, carbon emissions, and climate change are quite literally etched into the hard skeletons of the corals themselves.

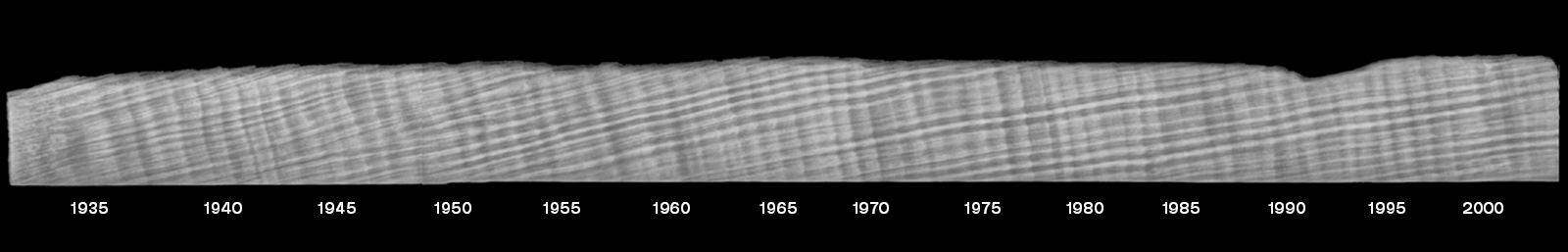

“I think of that skeletal material as a little time capsule,” said Amy Wagner, a scientist who studies corals to find clues about Earth’s past.

Back when she was a graduate student in 2005, Wagner and a team of scientists came to Flower Garden Banks in search of one very specific type of coral, Siderastrea siderea. “They just look like a bunch of rocks on the bottom,” she said.

The team dove down 78 feet, to the peaks of these ancient mountaintops, and drilled a nearly 6-foot-long core of this slow-growing species of coral — a 250-year record of pollution, climate change, and even world events. “You start to drill in and, especially in that initial drilling, you’re getting the tissue layer of the coral,” Wagner said. “And you end up having a lot of fish come in, because it’s free food, right?”

Amy Wagner’s team drills a coral sample from the Flower Garden Banks in 2005. Courtesy of Amy Wagner and John Halas

After hours of drilling, they patched up the hole and swam the 6-foot-long core to the surface. Back at the lab, they split open the core samples and x-rayed them. “They’re like trees,” Wagner said. “You can count the tree rings and go back in time. Corals produce these annual bands.”

Every year, the living coral organism lays down a new growth band, using the nutrients and minerals it pulls out of the seawater. Essentially, whatever’s in the seawater makes it into that year’s layer of coral skeleton. “So we have this long record of these little, tiny time capsules that are sort of locking in the ocean chemistry,” Wagner said.

Using a high-tech version of a dentist’s drill, Wagner and her colleague Kristine DeLong, a professor at Louisiana State University, collected a tiny bit of dust from each growth band. Then, like detectives, they analyzed different elements in the dust for clues, looking at the variations in the coral core over time.

Just like humans, corals build their skeletons out of calcium. But sometimes they make mistakes, accidentally grabbing look-alike elements from the seawater. One of those elements is barium, which is often used as a lubricant in offshore oil wells. During the 1970s energy crisis, oil drilling boomed in the Gulf of Mexico. And Wagner and DeLong could see that spike reflected in the barium levels in the coral: When oil prices crashed, production went down, and so did the barium.

There are many other histories scientists can see etched in this coral core. By looking at nitrogen, they can see the rise of fertilizer pollution from the Mississippi River. By looking at radioactive carbon, they can see the rise of nuclear weapons tests during the Cold War.

And the corals even tell the story of how fossil fuels are changing the climate — in the words of one scientist, “recording their own demise.” To see how, it’s important to know that carbon atoms aren’t all exactly the same. They actually come in a few different weights, depending on the number of neutrons in each carbon atom. A carbon atom with seven neutrons is called “heavy carbon,” while an atom with six neutrons is called “light carbon.” Plants prefer to use the light carbon for photosynthesis. So, inside of a plant, the carbon atoms tend to be a little bit lighter than those, say, inside of a volcano.

Fossil fuels come from ancient plants, which are full of light carbon. As fossil fuel emissions rise, the carbon atoms in our atmosphere are slowly getting lighter.

You can see this same trend playing out inside of the corals: The carbon in the coral slowly gets lighter in the band samples as the world burns more fossil fuels. As those fossil fuel emissions warm the climate, they put reefs around the world in danger.

Today, the Flower Garden Banks are still holding on, but they won’t be safe forever. As early as 2040, the Flower Garden Banks could start to see major bleaching events every summer. If we can reduce our emissions at a more reasonable pace, climate models say we might be able to buy an extra 15 to 20 years for the Flower Garden Banks — essentially doubling its window of time. That window would be critical for the sanctuary staff and independent scientists who are working hard to study and protect what might become one of the last coral reefs.

“Going to a place like Flower Gardens, it’s like — these corals, they’re still pretty darn healthy,” said DeLong. “Being able to manage those reefs and take care of them is important, because they may be the last ones we have.”

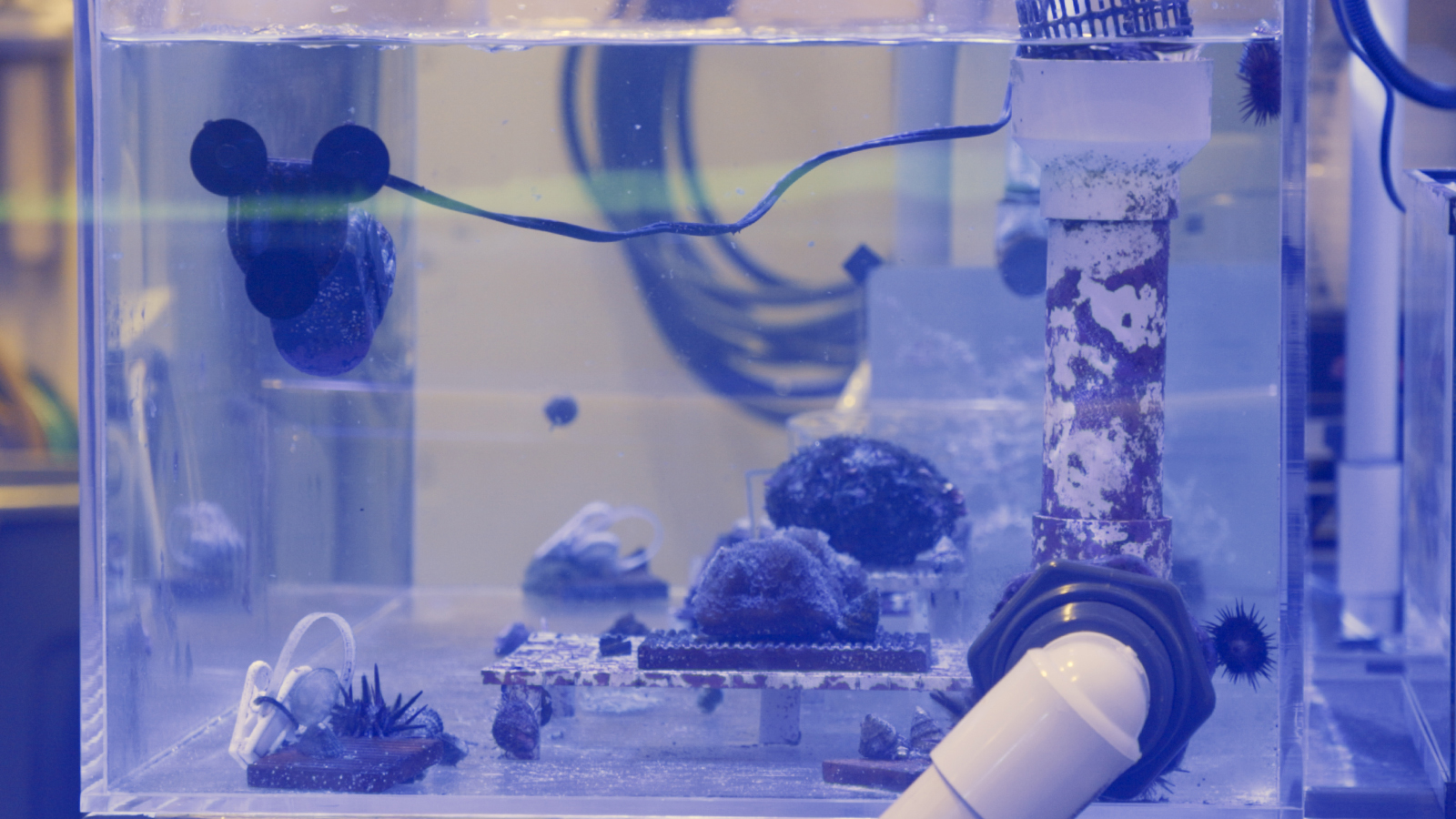

Recently, scientists at the Flower Garden Banks have started collecting corals from the reef and storing them in an onshore coral lab. The hope is to eventually bank enough coral here in case the worst happens.

“It is a grim prospect,” Johnston said. “It’s better to be proactive and have some things banked versus getting into the situation where all the corals have bleached and died and we have nothing left. It’s my hope that nature can figure things out and things can adapt. I think the problem is that the climate is changing quickly enough that there might not be time.”

The Flower Garden Banks are a product of 10,000 years of slow, steady growth, capturing annual snapshots of our world, in small millimeter-sized chapters. The next few decades will be critical in determining just how much longer this reef will be able to continue its ancient undersea story.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline The Gulf Coast is home to one of the last healthy coral reefs. It’s surrounded by oil. on May 9, 2024.

More so than any other fossil fuel company, Occidental Petroleum — known as Oxy — has built its climate strategy around innovations that capture carbon before it can be emitted or pull it directly out of the air. The Texas-based oil giant, which made more than $23 billion in revenue last year, says on its website that these “visionary technologies” will help it achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions and enable a lower-carbon future.

Scientists agree that such technologies will be necessary to limit global warming. But Oxy’s plans for them appear to be less about sustainability and more about creating a “license to pollute,” according to a new analysis from the nonprofit Carbon Market Watch. The analysis describes Oxy’s focus on carbon capture and removal as a “costly fig leaf for business as usual,” allowing the company to claim emissions reductions while continuing to profit from the sale of fossil fuels — rebranded as “net-zero oil” and “sustainable aviation fuels.”

The company “makes this whole spiel about meeting the Paris Agreement’s goals, but it’s very clearly flying in the face of that,” said Marlène Ramón Hernández, an expert on carbon removal at Carbon Market Watch and a co-author of the report. “What we have to do is phase out fossil fuels, not perpetuate their life.”

Oxy first outlined its net-zero strategy in 2020, making it the first American oil major to do so. Today, Oxy describes that strategy using four R’s: The company says it will “reduce” operational emissions, “revolutionize” carbon management, “remove” carbon from the atmosphere, and “reuse/recycle” it to produce new low-carbon or zero-emissions products. Its overarching goal is to achieve net-zero emissions for its operations and indirect energy use by 2040.

This is where the problems begin, according to Carbon Market Watch. Despite Oxy’s net-zero pledge for its operation and energy use, it is much vaguer about the emissions associated with the oil and gas it sells. These emissions, known as Scope 3 emissions, represented more than 90 percent of Oxy’s greenhouse gas footprint in 2022. The company has asserted an “ambition” to zero them out by 2050.

However, Oxy does not plan to reduce Scope 3 emissions by phasing down the production of oil and gas, but through investments in carbon removal. Direct air capture, or DAC — a technology that uses large fans and chemical reactions to separate carbon dioxide from the air — is a main focus. An Oxy subsidiary called Oxy Low Carbon Ventures announced in 2022 that it would deploy up to 135 DAC plants by 2035, and last year Oxy bought a major DAC technology company for $1.1 billion.

Some of Oxy’s DAC projects are already in the pipeline. The largest, called Stratos, is under construction in the Permian Basin, a massive oil field, in Texas. If it reaches its nameplate capacity of capturing half a million metric tons of carbon dioxide a year — which Oxy says it will do by mid-2025 — it will be 14 times larger than the biggest DAC facility in the world. (That facility, owned by the Swiss company Climeworks, began operating in Iceland this week with a nominal capacity of 36,000 metric tons of CO2 per year.)

In order for DAC to result in net removal of carbon dioxide, however, captured carbon has to be kept out of the atmosphere for good. This is usually achieved by locking it up in rock formations. Oxy CEO Vicki Hollub, however, has said this would be a “waste of a valuable product,” and instead plans to use the captured carbon. In one application, it would be converted into synthetic electrofuels — low-carbon fuels produced from their chemical constituents using electricity — and sold to other companies.

The other major application is for a process known as enhanced oil recovery, where CO2 is injected into oil and gas wells in order to extract hard-to-reach reserves of fossil fuels. This forms the basis for Oxy’s “net-zero oil” claims. According to the company’s logic, the atmospheric carbon dioxide injected into the ground cancels out any new emissions from the oil and gas it’s used to pull up. In an interview with NPR last December, Hollub said this approach means that “there’s no reason not to produce oil and gas forever.”

Before that, at a conference last March, Hollub told audience members that DAC would be “the technology that helps to preserve our industry over time,” extending its social license to operate for “60, 70, 80 years.”

Neither Carbon Market Watch nor the independent experts Grist spoke to look favorably on these approaches. Charles Harvey, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at MIT who was not involved in the report, called it “absurd” to use captured carbon to make so-called sustainable aviation fuels; these fuels will eventually be burned, re-releasing the captured carbon back into the atmosphere.

In fact, the whole process may result in a net increase in greenhouse gas emissions, since DAC is an energy-intensive process that is often powered by fossil fuels. Oxy has no publicly announced plans to power its carbon capture and removal facilities with renewable energy. “They’ll be releasing more CO2 than they’re capturing,” Harvey said.

As for “net-zero oil,” Carbon Market Watch calls it an “oxymoron and a logical fallacy.” A 2021 analysis by the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Energy Technology Laboratory suggests that this application would also result in net-positive emissions — both because it takes so much energy (likely supplied by fossil fuels) just to run a DAC plant, and, because every metric ton of carbon dioxide injected into oil fields extracts two to three barrels of oil. Each barrel of oil generates half a metric ton of carbon dioxide when burned, which means each metric ton of carbon dioxide used for Oxy’s net-zero oil may create 1 to 1.5 tons of CO2 emissions.

Hernández said she is also concerned about Oxy’s plans to generate carbon credits from its DAC projects. Even though none of its planned DAC facilities has been built yet, Oxy has already pre-sold or is in negotiations to sell DAC-generated carbon credits representing between 1.63 million and 1.98 metric tons of carbon dioxide, according to Carbon Market Watch’s calculations. If the company uses the same captured carbon to offset its own emissions and generate credits, which can be used to offset the emissions of another company, “This is a blatant issue of double-counting,” Hernandez told Grist.

Oxy did not respond to Grist’s request for comment.

Holly Jean Buck, an assistant professor of environment and sustainability at the University of Buffalo, said it’s possible to pursue DAC responsibly. Even a moonshot project like Stratos could be seen as having an important demonstration or research value. “The point is to figure out if the technology is going to work at a real-world level,” she told Grist.

That said, she agreed there are ways Oxy could make its DAC agenda more credible. “They could make a commitment to building renewable power to power it,” she offered, or donate the technology to developing countries.

Buck and some other academics say fossil fuel companies should be doing more of this research — or at least footing the bill for it — in order to take responsibility for their role in the climate crisis. Harvey, however, argues there’s an opportunity cost to such research and deployment, which is expensive. He and other researchers have estimated that it will cost Oxy’s Stratos facility $500 to capture each metric ton of carbon dioxide. (The company predicts costs will fall to around $200 per ton by 2030.)

Every dollar spent on DAC means a dollar not spent on more reliable, immediate emissions reductions. “There’s low-hanging fruit to do before you get there,” he said, like building renewable energy for non-DAC purposes, insulating houses, installing heat pumps, or putting more batteries on the grid with existing renewables.

“Almost anything is better” than DAC, Harvey said.

As an essential first step toward a more credible net-zero strategy, Hernández suggested that Oxy abandon its aggressive plans to extract more oil and gas, since doing so is misaligned with scientists’ call for a dramatic cut in production in order to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit). “It’s actually planning to increase its oil production, so there is clearly no intention there to transition to net-zero,” she said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Occidental Petroleum’s net-zero strategy is a ‘license to pollute,’ critics say on May 9, 2024.