When discarding plastic bottles, many recycling services now prefer you screw plastic tops on before…

The post Recycling Mystery: Metal Lids & Bottle Caps On Glass Containers appeared first on Earth911.

When discarding plastic bottles, many recycling services now prefer you screw plastic tops on before…

The post Recycling Mystery: Metal Lids & Bottle Caps On Glass Containers appeared first on Earth911.

Did you know about the direct connection between home composting and the health of our…

The post How You Can Help Create A Healthier Ocean By Composting appeared first on Earth911.

Pretty much all life on Earth – plants, animals, humans – in large part, owe their entire existence to one microscopic protein. It’s called ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase, better known as RuBisCO, and it’s an enzyme: a biological machine that helps turn CO2 into energy.

Of the millions of enzymes on earth, RuBisCO might be the most important. It’s essential to photosynthesis, and without it, plants would be unable to grow. Without RuBisCO, nearly all life on Earth would starve.

But even though it’s everywhere, and has been around for billions of years, RuBisCO kind of sucks at its job. And it’s getting worse as the world gets hotter.

Today, a global team of scientists is trying to accomplish something that evolution has previously failed to do: building a better RuBisCO.

RuBisCO was discovered kind of by accident. It was the 1940s, and an aimless grad student named Sam Wildman stumbled on a newly-released book about plant science in his university library. The book described a simple way to get protein from leaves, using common lab ingredients. Curious, and maybe a bit bored, Wildman started messing around in the lab.

When he added a certain chemical to the spinach juice, a giant cloud of protein would appear. He didn’t know it at the time, but that cloud was RuBisCO. He had just discovered the enzyme directly responsible for taking CO2 from the air and kickstarting photosynthesis. He also had no idea that that cloudy test tube contained a clue that would haunt scientists for the next eight decades.

You can think of photosynthesis kind of like a big assembly line that takes in CO2 and, step by step, turns it into food. Each stop on the assembly line is an enzyme: little biological machines that each perform a step. And if they all work together, the plants can suck up a lot of carbon, make a lot of food, and the whole operation runs like clockwork.

Unfortunately, that’s not what happens, because of one incompetent enzyme: RuBisCO. The first problem is that it’s really slow, hundreds of times slower than many other enzymes. And it ends up slowing down the entire factory, resulting in a lot less food.

Second, it makes a lot of mistakes. Instead of grabbing CO2, RuBisCO will often grab an oxygen molecule. This wreaks havoc on the assembly line, and the entire operation has to go into cleanup mode. This happens so often that plants waste nearly a third of their energy fixing this sloppy mistake.

Finally, this enzyme performs even worse during hot weather. This means that as climate change warms our planet, our farms may produce less food, and our plants could get worse at sequestering carbon.

In the face of all of these problems, plants have developed an incredibly makeshift workaround:

They just make tons and tons of RuBisCO. This is why there was so much of that cloudy protein in Sam Wildman’s test tube. RuBisCO alone makes up nearly half of the protein in leaves of spinach and many other plants.

Soon after its discovery, scientists started to wonder if a better RuBisCO was possible. They envisioned futuristic plants that could produce higher yields and suck up more carbon. They saw it as a way to feed the world’s growing population, and the billions more to come — not through bigger farms or more fertilizer, but by improving the fundamental nature of plants.

On the other hand, neither billions of years of evolution nor decades of scientific research had fixed RuBisCO’s problems. To some, this is a sign that a better RuBisCO isn’t possible. The lack of progress seems so hopeless that one source told me that scientists are sometimes hesitant to even admit they’re working on this challenge.

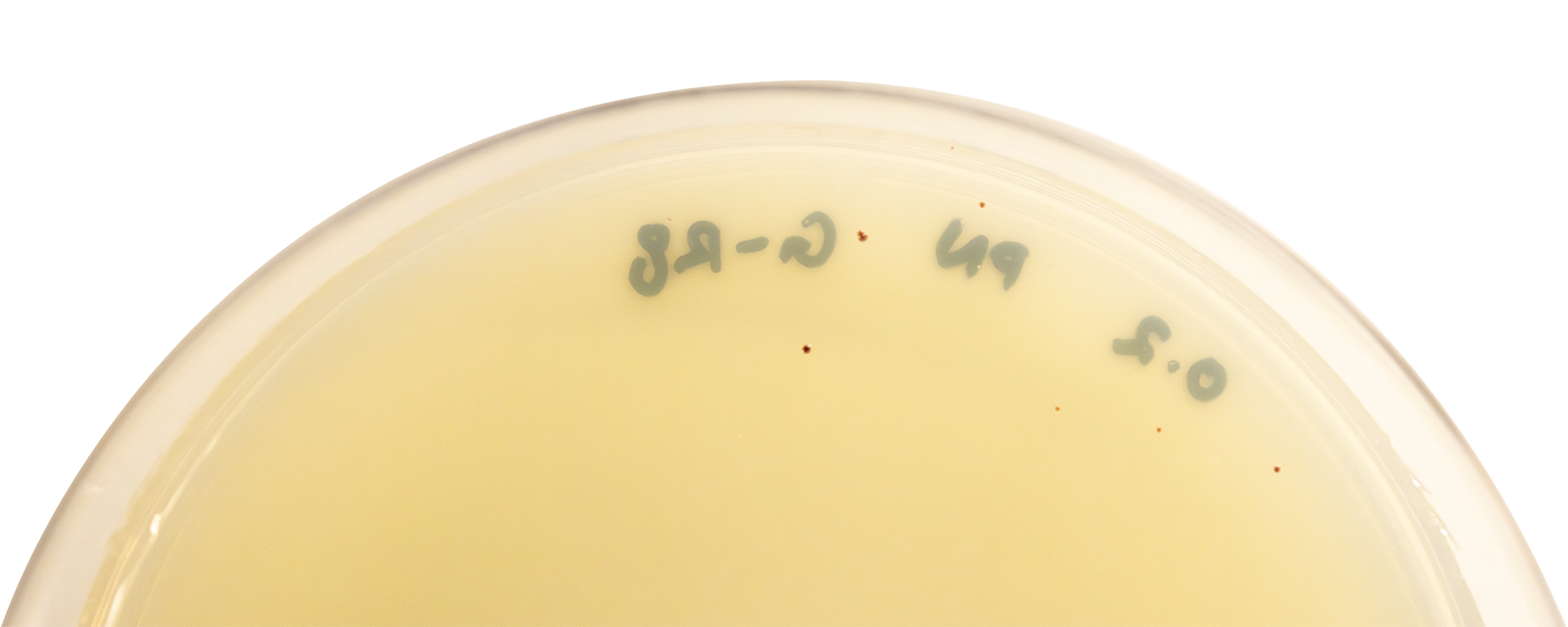

But not everyone sees it that way. Robbie Wilson is a research scientist and a self-described “rubiscologist” at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He’s one of the scientists who see this evolutionary paradox as more of a challenge. Wilson is part of an international collaboration aimed at evolving a better RuBisCO — not in a field, or even a greenhouse, but in a petri dish of bacteria.

Evolution usually takes place over millions of years. But with bacteria, scientists are able to speed this process up. Bacteria are pretty simple to modify genetically, meaning scientists can actually design their own sequences instead of waiting for random mutations. And their generations are only about 25 minutes long. “I’d say it makes it a million times better — maybe a billion times easier — to work with bacteria,” Wilson said.

This is what’s so special about Wilson’s technique: He’s found a way to engineer bacteria to create and test thousands of different versions of RuBisCO in the lab. Just like in the wild, where threats like predators and diseases push species to develop certain strengths, Wilson’s designed a special lab environment to push the bacteria to develop better forms of RuBisCO.

Once each bacteria colony has produced a slightly different version of RuBisCO, Wilson and his team essentially poison the bacteria. The poison comes from a second enzyme, called phosphoribulokinase, or PRK.

Like RuBisCO, this enzyme is an important part of photosynthesis in plants. In nature, PRK produces a chemical that RuBisCO needs to do its job — capturing carbon and turning it into food. But in the petri dish, that same chemical can be deadly. The bacteria isn’t designed for photosynthesis, so unless RuBisCO acts quickly, that chemical will just build up until it eventually kills the entire colony of bacteria.

RuBisCO is essentially an antidote to this poison. The better the RuBisCO, the healthier the bacteria.

On a recent visit to Wilson’s lab at MIT, I watched as he pulled out two petri dishes from the experiment. This first petri dish contained RuBisCO you’d find in nature — which wasn’t very good, so the petri dish was empty. The second petri dish was full of bacteria with new versions of RuBisCO. That dish was covered in little dots. Those bacteria colonies were surviving because their new RuBisCO enzymes worked really well.

Wilson was seeing evolution — but happening in hours instead of millions of years.

Once the team has identified the best candidates in the petri dish, they need to see if the new versions of RuBisCO actually work in real plants. Using a syringe, they inject the new DNA into the plants. You can actually see the liquid spreading through the leaf. Those plants will go on to produce the brand new versions of RuBisCO, and Wilson’s team will see if they actually do grow better in the real world.

While it’s still a long process from the lab to the field, Wilson is hoping that this project might finally demonstrate that a better RuBisCO actually is possible. “I’m secretly pretty confident that we’re going to change the way that people think about RuBisCO’s engineering potential, which is going to have a huge knock-on effect for continuing research,” he said.

But as important as improving RuBisCO is, it’s just one part of the enormous effort to develop more productive and climate-resilient crops. Right now, other scientists are thinking up ways to make plants that can capture more colors of sunlight, or dreaming up projects that build on the natural workarounds that certain plants have developed to circumvent RuBisCO’s weaknesses.

“There have been very encouraging results from many other projects that have gotten me really excited,” Wilson said. “I think if all of these can be combined together, we’re gonna have something really special.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline This enzyme is responsible for life on Earth. It’s a hot mess. on May 16, 2024.

In the depths of the Great Depression in 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt warned Congress that millions of Americans were idly “walking the streets,” presenting a threat to the country’s stability, even though they “would infinitely prefer to work.” It’s part of the reason he proposed the Civilian Conservation Corps, a program that would hire men to preserve forests, prevent soil erosion, and control floods. “More important, however, than the material gains will be the moral and spiritual value of such work,” Roosevelt said.

President Joe Biden referenced that line last month when he announced the launch of the American Climate Corps, a government jobs program inspired by Roosevelt’s that tackles the environmental problems of the 21st century. Besides the obvious benefits of restoring wetlands and installing solar panels, the climate corps is intended to pave a path to green careers for those who sign up. Another advantage of joining, though less-discussed, is that it could help alleviate widespread climate anxiety, channeling young people’s concern into concrete, hands-on work. More than half of Americans are anxious, to some degree, about how climate change is affecting their mental health. There are only about 250 job openings in the climate corps right now, but the White House expects to employ 20,000 people over the program’s first year.

While the vast majority of 18- to 28-year-olds in the United States say they’re worried about climate change, two-thirds of them are unsure what they can do to make a difference, according to polling from the think tank Data for Progress in 2022. The combination is ripe for “climate anxiety,” a catch-all term for the feelings of grief, fear, and distress that’s not so much a clinical diagnosis as a logical response to living through the hottest period on Earth in 125,000 years.

According to common wisdom, the best way to treat existential dread about global warming is to “take action.” But not all types of climate action are equal. Proponents of the American Climate Corps suggest that the program offers something more substantial than ditching meat or taking a bike ride — it’s a chance to work on climate change or environmental justice issues all day as part of a larger cause. “There’s something about, ‘Here is a clear job with a clear timeline and a clear local goal. I can, like, put my hands in the dirt,’” said Kidus Girma, campaign director of the Sunrise Movement, a youth-led climate organization that fought to make the climate corps happen.

In small doses, anxiety can prompt people to do something, but in large doses, it can be incapacitating. The structure of the American Climate Corps could be useful for young people who are overwhelmed by the enormity of a global problem and aren’t sure where to start, said McKenna Parnes, a clinical psychology researcher at the University of Washington.

Taking action as part of a group, as opposed to going it alone, can significantly alleviate the distress associated with climate change, according to a study Parnes co-authored in 2022. Climate corps members wouldn’t necessarily need to be working with people all day to get those benefits. “Even if it’s folks that are doing individual jobs but part of the greater collective, just by nature of being part of the climate corps, there’s already that collective piece,” she said.

Jennifer Rasmussen, a registered nurse and an education fellow with the Planetary Health Alliance, a global network of organizations addressing the health effects of environmental changes, said that social support networks are key for improving mental health, especially with the rise of loneliness among young people. Being a member of the corps could also provide a sense of purpose and fulfillment, as well as help people build self-confidence by learning new skills — all of which tend to increase people’s psychological resilience and well-being, she said.

Roosevelt might have been ahead of his time when he wished the initial Civilian Conservation Corps members a “pleasant, wholesome, and constructively helpful stay in the woods.” Recent research suggests that feeling a connection to nature is associated with lower levels of depression and anxiety, another promising sign for American Climate Corps members who end up tending to forests, streams, or community gardens.

Climate anxiety comes in different forms: It can spring from a disaster, such as living through a flood, hurricane, or smoke-filled wildfire season. It can also take the shape of some existential dread about the future, even if you haven’t experienced a disaster yourself. A survey in 2021 found that climate anxiety was common in 10 countries across four continents, with 45 percent of young people saying that worrying about the environment was affecting their daily lives and ability to function.

That report suggested that this emotional distress stemmed from governments’ failure to respond to the problem. That rings true for Matt Ellis-Ramirez, a coordinator at Sunrise Movement Miami who recently graduated from the University of Miami and is thinking about joining the American Climate Corps. In Florida, for instance, a bill that removes most mentions of climate change from the state’s laws was signed by Governor Ron DeSantis on Wednesday, and last month, DeSantis signed legislation that bans local rules to protect outdoor workers from extreme heat.

“I think that’s where my anxiety comes from — that if we’re not actually able to shift our political system, that we might actually just be watching Miami become unlivable,” Ellis-Ramirez said.

Ellis-Ramirez is most excited about applying for hands-on positions in the American Climate Corps, like restoration efforts in the Everglades or planting trees in neighborhoods that lack them. Girma said that if he was looking for a job in the corps, he’d like to work on coastal restoration. “But I don’t think I would confidently say coastal restoration is the thing for people who have anxiety,” he said. “I think it’s broadly like, ‘Can I see a clear, measurable impact from my work day to day?’”

Saul Levin, the legislative and political director at the Green New Deal Network, says that there’s something empowering about knowing that people are working around you to address climate change and make communities safer. “It’s really not just the thousands and thousands of people who will be employed through the [American Climate Corps] who I think could have had their mental health improved, but also their acquaintances, families, neighbors, who similarly will benefit from knowing that folks are actually being hired to work on this.”

This story has been updated to reflect Governor DeSantis’ signing of a bill.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline The American Climate Corps will get people into green jobs. Can it help their mental health too? on May 16, 2024.

The rising cost of homeowner’s insurance is now one of the most prominent symptoms of climate change in the United States. Major carriers like State Farm and Allstate have pulled back from offering fire insurance in California, dropping thousands of homeowners from their books, and dozens of small insurance companies have collapsed or fled from Florida and Louisiana following recent large hurricanes.

The problem is fast becoming a crisis that stretches far beyond the nation’s coastal states. That’s owing to another, less-talked-about kind of disaster that has wreaked havoc on states in the Midwest and the Great Plains, causing billions of dollars in damage. In response, insurers have raised premiums higher than ever and dropped customers even in inland states such as Iowa.

These so-called “severe-convective storms” are large and powerful thunderstorms that form and disappear within a few hours or days, often spinning off hail storms and tornadoes as they shoot across the flat expanses of the central United States. The insurance industry refers to these storms as “secondary perils”—the other term of art is “kitty cats,” a reference to their being smaller than big natural catastrophes or “nat cats.”

But the damage from these secondary perils has begun to add up. Losses from severe convective storms increased by about 9 percent every year between 1989 and 2022, according to the insurance firm Aon. Last year these storms caused more than $50 billion in insured losses combined—about as much as 2022’s massive Hurricane Ian. No single storm event caused more than a few billion dollars of damage, but together they were more expensive than most big disasters. The scale of loss sent the insurance industry reeling.

“As insurers, our job is to predict risk,” said Matt Junge, who oversees property coverage in the United States for the global insurance giant Swiss Re. “What we’ve missed is that it wasn’t a big event that had a big impact, it was a bunch of small surprise events that just added up. There’s this kind of this reset where we’re saying, ‘Okay, we really have to get a handle on this.’”

Part of the reason for this steady accumulation is that more people are moving to areas that are vulnerable to convective storms, which raises the damage profile of each new tornado or hailstorm. The cost of rebuilding a home has increased due to inflation and supply-chain shortages, which drives up prices. But climate change may also be playing a role: Convective storms tend to form in hot, moist, and unstable weather conditions.

“We have such a dearth of observations about hailstorms and tornadoes, so the trend analysis is tricky,” said Kelly Mahoney, a research scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, who studies severe convective storms. “But you are taking storms that are fueled by heat and moisture, and you are watching them develop in a world that is hotter and moister than ever. It’s a tired analogy these days, but it’s still true here, of loaded dice or a stacked deck.”

Climate attribution is much harder for these ephemeral storms than it is for hurricanes and heat waves, Mahoney said, but it stands to reason that climate change will have some influence on how and where they develop. Warming has already caused the geographic range of “Tornado Alley” to extend farther south and east than it once did, delivering more twisters to states like Alabama and Mississippi.

Whatever the cause, this loss trend is making business much harder for many insurance companies. Most vulnerable are the small regional insurers with large clusters of customers in one state or metropolitan area. When a significant storm strikes, these companies have to pay claims to huge portions of their risk pool, which can drain their reserves and push them toward insolvency.

“The local mutuals, you have a couple storms, you have a bad year, and they’re in trouble, because all their business is here and that risk isn’t spread out,” said Glen Mulready, the insurance commissioner of Oklahoma. The state has some of the highest insurance premiums in the country, and Mulready said many insurers are now refusing to write new policies for homes with old roofs that are vulnerable to collapse during tornadoes and hailstorms.

Even large “reinsurers,” which sell insurance to insurance companies around the world, are feeling the sting from these storms. Global reinsurance firms such as Swiss Re take in premium revenue from all over the globe, insuring earthquakes in Japan as well as hurricanes in Florida, so they aren’t vulnerable to collapse during local disasters, even major ones. But the increasing trend of “attritional” losses from repeated convective storms does threaten to cut into their profit margins.

“We have less of a concern about the tail on these types of events,” said Junge of Swiss Re, using the industry term for the costliest disasters. “The concern for us is just the impact on earnings.”

Ed Bolt, the mayor of Shawnee, Oklahoma, has seen this impact up close. A tornado raged down his town’s main boulevard last year and destroyed more than 2,000 buildings, knocking the roof off Bolt’s own house. His insurance company paid to replace the roof, but it mailed him a letter a few months ago with a notice that his annual premium was going to increase by 50 percent, reaching around $3,600 a year.

“The cost used to tick up and tick up a little bit, but last year we knew we would get a big hit because of the tornado,” Bolt told Grist. “I’m sure that would be a pretty consistent experience across town.”

Most states require insurers to get permission from regulators before they raise rates, which presents governments with a tough dilemma. If they raise rates, they make it harder for homeowners to keep up with their insurance payments, and they also risk dampening property values. If they keep rates down, insurers might react by ceasing to write new policies or pulling out of the state. Mulready, the Oklahoma commissioner, says he had one national insurer leave his market earlier this year.

Still, the Midwest has yet to encounter a large-scale exodus, and industry representatives say it’s unlikely that they will pull out of the region the way they have from California. But it’s a safe bet that insurers will keep raising premiums as high as states will let them. Insurers may also raise deductibles, setting a higher minimum amount of damage before insurance kicks in. The upshot is a bigger financial burden for homeowners in fast-growing metro areas like Denver, where insurers’ storm exposure has skyrocketed in recent years.

Perhaps the worst part of the problem is that most states have made little progress in preparing for these storm events. Florida imposed a strict building code after Hurricane Andrew in 1992, and most newer homes in the state can withstand high winds. The housing stock in the central United States is far less resilient to tornado winds and hail, and just a few cities have forced builders to fortify homes against those hazards.

Erin Collins, the lead state policy advocate at the National Association of Mutual Insurance Companies, the nation’s largest insurer trade group, said carriers might have to keep raising rates until the nation’s housing stock becomes more resilient to severe storms.

“It’s going to take community-scale hardening to bend that loss curve down,” she told Grist.

That won’t be easy. Insurers need to convince large home builders that they should build with more expensive, storm-resistant materials, and they also need to nudge millions of people in existing homes to upgrade their roofs and windows, which can cost tens of thousands of dollars. Because severe convective storms can strike such a wide geography, it will take a long time for this mitigation work to “bend the loss curve down.”

The good news is that we know how to build storm-resistant homes, and there’s proof that building better makes a big difference, says Ian Giacomelli, a senior meteorologist at the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety, a nonprofit that advocates for stronger building standards.

Giacomelli points to the city of Moore, Oklahoma, which rolled out some of the strictest storm-resilience standards in the country after it suffered three devastating tornadoes in two decades. Now almost the city’s entire housing stock has roofs that can bounce off large hail storms and strong joints that prevent roofs from flying off during tornado events. Giacomelli says the nation’s current insurance crisis would likely ease up if more cities followed Moore’s lead.

“I think the solutions are coming into focus,” he told Grist. “It’s more about can we get the will to do them.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How ‘kitty cats’ are wrecking the home insurance industry on May 16, 2024.

Bumblebees are essential pollinators, but many species are in a downward spiral that is sometimes a mystery to scientists.

In a new study, researchers have found that the increasing temperatures of the human-caused climate crisis may be interfering with climate control in bumblebee nests, threatening future generations.

“The decline in populations and ranges of several species of bumblebees may be explained by issues of overheating of the nests and the brood,” said lead author of the study Dr. Peter Kevan of Canada’s University of Guelph, in a press release from Frontiers. “The constraints on the survival of the bumblebee brood indicate that heat is likely a major factor, with heating of the nest above about 35 degrees Celsius being lethal, despite the remarkable capacity of bumblebees to thermoregulate.”

There are more than 250 species of bumblebee on Earth, inhabiting a variety of environments. Many are in decline due to climate change, but the specific cause has been difficult to pinpoint.

Following a review of the scientific literature, the research team found that the optimal temperature window of bumblebee nests — roughly 28 to 32 degrees Celsius — was consistent between many species around the world.

“We can assume that the similarity reflects the evolutionary relatedness of the various species,” Kevan said in the press release.

The right temperature means minimal metabolic expenditure, while warmth in excess of that window can lead to dangerous heat stress. This means adaptation to higher temperatures could prove hard for bumblebees.

“Excessively high temperatures are more harmful to most animals and plants than cool temperatures. When conditions are cool, organisms that do not metabolically regulate their body temperatures simply slow down, but when temperatures get too high metabolic processes start to break down and cease,” Kevan explained. “Death ensues quickly.”

After a review of 180 years of literature, the team discovered that bumblebees seemed to survive at temperatures as high as 36 degrees Celsius, while 30 to 32 degrees was the optimal range for development, though that window could differ between biogeographical conditions and species.

“The similarity of the optimum temperature range in incubating nests is remarkable, about 28–32°C regardless of species from the cold High Arctic to tropical environments indicates that the optimal temperature for rearing of brood in Bombus spp. is a characteristic common to bumblebees (perhaps a synapomorphy) and with limited evolutionary plasticity,” the researchers wrote in the study.

The researchers said that, while bumblebees have a number of behavioral adaptations for thermoregulation, they may not be adequate to adapt to climate change. They called for more research on how the pollinators can survive the rising temperatures, as well as more studies into bumblebee ecology — temperature, thermoregulation, nest morphology and material properties.

A bumblebee colony acts as a “superorganism,” with reproductive fitness dependent on collective reproduction and survival rather than on individual bees, the press release said. Individual bees may be better able to cope with heat than others, but if the bees’ nest is too hot for raising healthy larvae, the entire colony will suffer.

“The effect of high nest temperatures has not been studied very much, which is surprising. We can surmise that nest temperatures above the mid-30s Celsius would likely be highly detrimental and that above about 35 Celsius death would occur, probably quite quickly,” Kevan said in the press release.

Honeybee studies have shown that hotter nest temperatures sap the strength of queen bees and weaken their ability to reproduce, leading to smaller worker bees and less optimum conditions. If heat affects bumblebees in a similar way, global heating could be a direct cause of their decline.

Some bumblebee colonies may be able to adapt the selection and form of nest site or their behavior to cool down their nests. Ground-penetrating radar might aid in the study of ground-nesting bee species and nest analysis using flow-through respirometry at varying temperatures could help researchers assess how much stress is being placed on bee colonies inside.

“We need both to understand how different colonies cope with the same conditions and how different species cope with different conditions, including whether some bumblebee species have broader thermal neutral zones, affording them more resilience,” the press release said.

“We hope that future scientists may take the ideas we present and apply them to their own research on bumblebee health and conversation,” Kevan concluded.

The study, “Thermodynamics, thermal performance and climate change: temperature regimes for bumblebee (Bombus spp.) colonies as examples of superorganisms,” was published in the journal Frontiers in Bee Science.

The post Bumblebee Populations Threatened by Nests Overheating Due to Climate Change appeared first on EcoWatch.

Humans and other animals have the ability to teach important skills to their contemporaries that allow for knowledge building across generations.

According to two new studies, bumblebees and chimpanzees are two animals who have the capability of learning skills so complex they would never have been able to master them alone — an ability scientists previously believed was unique to humans.

“Culture refers to behaviours that are socially learned and persist within a population over time. Increasing evidence suggests that animal culture can, like human culture, be cumulative: characterized by sequential innovations that build on previous ones,” the bumblebee study said.

“Cumulative culture” is the human capacity to build knowledge, skills and technology over time while improving upon them as they are taught to successive generations, reported AFP. It is a technique that is viewed as an essential part of humans’ dominance over their environment.

“Imagine that you dropped some children on a deserted island,” said Lars Chittka, co-author of the study on bees and a behavioral ecologist at London’s Queen Mary University, in a video accompaniment to the study, as AFP reported. “They might — with a bit of luck — survive, but they would never know how to read or to write because this requires learning from previous generations.”

Earlier experiments had shown that some animals demonstrate “social learning,” where they figure out a skill through observation of individuals of their own species. But while some of the behaviors appeared to have been honed over time — such as the ability of chimpanzees to crack open nuts or the navigational skills of homing pigeons — it is hard for scientists to eliminate the possibility that these animals did not figure out how to accomplish the specific tasks on their own.

A research team from the United Kingdom looked at bumblebees to determine whether they had some of the characteristics of cumulative culture.

First they trained a group of “demonstrators” to perform a complicated skill that could be passed on to others.

They gave some of the bees a two-step puzzle box that involved pushing a blue tab followed by a red tab that released a sugary reward.

“This task is really difficult for bees because [during the first step] we are essentially asking them to learn to do something in exchange for nothing,” Alice Bridges, co-author of the study and a Ph.D. student at Queen Mary University, told AFP.

The bees initially attempted to only push the red tab without moving the blue tab first, then gave up.

In order to motivate them, the team placed the sugary prize at the end of the blue tab, then took the reward away gradually as they mastered the task.

The researchers then paired the demonstrator bees with “naive” bees unfamiliar with the process who watched their peers solve the puzzle.

Of the 15 new bees, five quickly solved the puzzle with no prize during the first step. Naive bees who were not taught how to obtain the treat were still not able to open the box after extended exposure for as long as 24 days.

Bridges said the team was “surprised” and thrilled when they saw the swift learning behavior.

They said the study was the first to observe an invertebrate species demonstrating cumulative culture.

“This finding challenges a common opinion in the field: that the capacity to socially learn behaviours that cannot be innovated through individual trial and error is unique to humans,” the study said.

The study, “Bumblebees socially learn behaviour too complex to innovate alone,” was published in the journal Nature.

The second study showed that humans’ closest living relatives — chimpanzees — also have the ability to learn from their contemporaries.

The Dutch-led research team set up a puzzle box to be solved by a semi-wild chimpanzee troupe at Zambia’s Chimfunshi Wildlife Orphanage.

The task involved first retrieving a wooden ball, then holding a drawer open, putting the ball in and closing it to get a peanut at the end.

During the course of three months, 66 chimpanzees attempted but were not able to solve the puzzle.

The team then trained two demonstrator chimpanzees who showed their peers how to do it.

Within two months, 14 of the naive chimpanzees had mastered the puzzle. What’s more, the researchers discovered that the more often they observed the demonstrators, the faster they were able to solve it.

The study, “Chimpanzees use social information to acquire a skill they fail to innovate,” was published in the journal Nature Human Behavior.

Bridges said both studies “can’t help but fundamentally challenge the idea that cumulative culture is this extremely complex, rare ability that only the very ‘smartest’ species — e.g. humans — are capable of.”

The post Like Humans, Bumblebees and Chimpanzees Can Pass on Their Skills to Form ‘Cumulative Culture’ appeared first on EcoWatch.

After studying tree rings from the past 2,000 years, researchers have found that the Northern Hemisphere experienced its hottest summer in 2023 in the past two millennia.

The researchers used both observed and modeled surface air temperatures for the period from June to August each year, along with 2,000 years of tree ring data. Their results, published in the journal Nature, showed that summer 2023 in the Northern Hemisphere was the hottest since the height of the Roman Empire.

“When you look at the long sweep of history, you can see just how dramatic recent global warming is,” Ulf Büntgen, co-author of the study and professor at University of Cambridge’s Department of Geography, said in a statement. “2023 was an exceptionally hot year, and this trend will continue unless we reduce greenhouse gas emissions dramatically.”

Additionally, the findings revealed that the Northern Hemisphere has already surpassed the 1.5-degree-Celsius limit outlined in the Paris Agreement, a target meant to curb global warming and prevent the worst impacts of climate change.

In September 2023, the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) found that the period from June through August 2023 was the hottest summer on record. Further, C3S predicted in December of last year that 2023 would be named the warmest year on record.

As the researchers of the new study pointed out, records are often limited either by location or by date, with instrumental evidence of warming typically dating back to about 1850 or later. The older recorded data can also be inconsistent.

Tree rings helped fill gaps of knowledge and provide more accurate measurements of historic summer temperatures, and the study confirmed the record-breaking summer heat.

The researchers linked many of the warmer summers in the tree ring data to El Niño events, but they noted that rising emissions and global warming have led to stronger El Niño events, like the one experienced in 2023.

“It’s true that the climate is always changing, but the warming in 2023, caused by greenhouse gases, is additionally amplified by El Niño conditions, so we end up with longer and more severe heat waves and extended periods of drought,” said Jan Esper, lead author of the study and professor at the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz in Germany. “When you look at the big picture, it shows just how urgent it is that we reduce greenhouse gas emissions immediately.”

The study authors reported that El Niño could bring record-breaking temperatures in the early summer this year, although forecasters at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have found evidence of a weakening El Niño last month. NOAA officials have also predicted a 69% of a La Niña event by July to September.

A La Niña event, which could last from summer through early winter or longer, could bring other detrimental climate impacts. This climate event could bring frequent tropical storms and hurricanes to the eastern U.S., PBS reported, along with increased risks for drought and wildfires in the southwestern U.S.

The post Summer 2023 Was Hottest Summer in the Northern Hemisphere in 2,000 Years, Study Finds appeared first on EcoWatch.

By: Derrick Z. Jackson

Earlier this month, the Environmental Protection Agency announced it would regulate two forms of PFAS contamination under Superfund laws reserved for “the nation’s worst hazardous waste sites.” EPA Administrator Michael Regan said the action will ensure that “polluters pay for the costs to clean up pollution threatening the health of communities.”

That was an encore to the Food and Drug Administration announcing in February that companies will phase out food packaging with PFAS wrappings and the mid-April announcement by Regan that the EPA was establishing the first-ever federal limits on PFAS in drinking water. At that time, he declared, “We are one huge step closer to finally shutting off the tap on forever chemicals once and for all.”

One can forever hope the tap will be eventually shut, since it took seemingly forever for the nation to begin to crack down on this class of per-and polyfluoroalkyl synthetic chemicals. The chemical bonds of PFAS, among the strongest ever created, resulted in an incredible ability to resist heat, moisture, grease and stains. PFAS chemicals seemed like miracle substances in the 20th-century quest for convenience. They became ubiquitous in household furnishings, cookware, cosmetics, and fast-food packaging, and a key component of many firefighting foams.

The bonds are so indestructible they would impress Superman. They don’t break down in the environment for thousands of years, hence the “forever” nickname. Unfortunately for humans, the same properties represent Kryptonite.

Today, the group of chemicals known as PFAS is the source of one of the greatest contaminations of drinking water in the nation’s history. Flowing from industrial sites, landfills, military bases, airports, and wastewater treatment discharges, PFAS chemicals, according to the United States Geological Survey, are detectable in nearly half our tap water. Other studies suggest that a majority of the US population drinks water containing PFAS chemicals—as many as 200 million people, according to a 2020 peer-reviewed study conducted by the Environmental Working Group.

No one escapes PFAS chemicals. They make it into the kitchen or onto the dining room table in the form of non-stick cookware, microwave popcorn bags, fast-food burger wrappers, candy wrappers, beverage cups, take-out containers, pastry bags, French-fry and pizza boxes. They reside throughout homes in carpeting, upholstery, paints, and solvents.

They are draped on our bodies in “moisture-wicking” gym tights, hiking gear, yoga pants, sports bras, and rain and winter jackets. They are on our feet in waterproof shoes and boots. Children have PFAS in baby bedding and school uniforms. Athletes of all ages play on PFAS on artificial turf. PFAS chemicals are on our skin and gums through eye, lip, face cosmetics, and dental floss. Firefighters have it in their protective clothing.

As a result, nearly everyone in the United States has detectable levels of PFAS in their bodies. There is no known safe level of human exposure to these chemicals. They are linked to multiple cancers, decreased fertility in women, developmental delays in children, high cholesterol, and damage to the cardiovascular and immune systems. A 2022 study by researchers from Harvard Medical School and Sichuan University in China estimated that exposure to one form of PFAS (PFOS, for perfluorooctane sulfonic acid), may have played a role in the deaths of more than 6 million people in the United States between 1999 and 2018.

As sweeping as PFAS contamination is, exposures in the United States are also marked by clear patterns of environmental injustice and a betrayal to military families. An analysis by the Union of Concerned Scientists found that people of color and low-income people were more likely to live near non-military sources of PFAS contamination than wealthier, white people.

Another study by UCS found that 118 of 131 military bases had PFAS contamination concentrations at least 10 times higher than federal risk levels. A federal study last year found a higher risk of testicular cancer for Air Force servicemen engaged in firefighting with PFAS foams.

In the end, the whole nation was betrayed, in a manner straight out of the tobacco disinformation playbook. Behind the image of convenience, manufacturers long knew that PFAS chemicals were toxic. Internal documents uncovered over the years show how DuPont and 3M, the two biggest legacy makers of PFAS, knew back in the 1960s that the compounds built up in blood and enlarged the livers of laboratory animals. By 1970, a DuPont document referring to a PFAS chemical under its famed “Teflon” trademark said that it “is highly toxic when inhaled and moderately toxic when injected.”

By the late 1970s, DuPont was discovering that PFAS chemicals were affecting the liver of workers and that plant employees were having myocardial infarctions at levels “somewhat higher than expected.” But that did not stop the industry from downplaying the risk to workers.

One internal 3M document in 1980 claimed that PFAS chemicals have “a lower toxicity like table salt.” Yet, a study last year of documents by researchers at the University of California San Francisco and the University of Colorado found that DuPont, internally tracking the outcome of worker pregnancies in 1980 and 1981, recorded two cases of birth defects in infants. Yet, in 1981, in what the researchers determined was a “joint” communication to employees of DuPont and 3M, the companies claimed: “We know of no evidence of birth defects” at DuPont and were “not knowledgeable about the pregnancy outcome” of employees at 3M who were exposed to PFAS.

The same suppression and disinformation kept government regulators at bay for decades. The San Francisco and Colorado researchers found internal DuPont documents from 1961 to 1994 showing toxicity in animal and occupational studies that were never reported to the EPA under the Toxic Substances Control Act. As one example, DuPont, according to a 2022 feature by Politico’s Energy and Environment News, successfully negotiated in the 1960s with the Food and Drug Administration to keep lower levels of PFAS-laden food wrapping and containers on the market despite evidence of enlarged livers in laboratory rats.

Eventually, the deception and lies exploded in the face of the companies, as independent scientists found more and more dire connections to PFAS in drinking water and human health and lawsuits piled up in the courts. Last year, 3M agreed to a settlement of between $10.5 billion and $12.5 billion for PFAS contamination in water systems around the nation. DuPont and other companies agreed to another $1.2 billion in settlements. That’s not nothing, but it is a relatively small price to pay for two industrial behemoths that have been among the Fortune 500 every year since 1955.

In the last two decades, the continuing science on PFAS chemicals and growing public concern has led to a patchwork of individual apparel and food companies to say they will stop using PFAS in clothes and wrapping. Some states have enacted their own drinking water limits and are moving forward with legislation to restrict or ban products containing PFAS. In 2006, the EPA began a voluntary program in which the leading PFAS manufacturers in the United States agreed to stop manufacturing PFOA, one of the most concerning forms of PFAS.

But companies had a leisurely decade to meet commitments. Even as companies negotiated, a DuPont document assumed coziness with the EPA. “We need the EPA to quickly (like first thing tomorrow) say the following: Consumer products sold under the Teflon brand are safe. . .there are no human health effects to be caused by PFOA [a chemical in the PFAS family].”

Two years ago, 3M announced it will end the manufacture of PFAS chemicals and discontinue their application across its portfolio by the end of next year. But the company did so with an insulting straight face, saying on its products are “safe and effective for their intended uses in everyday life.”

The nation can no longer accept the overall patchwork or industry weaning itself off PFAS at its own pace. The EPA currently plans to issue drinking water limits for six forms of PFAS and place two forms under Superfund jurisdiction. The Superfund designation gives the government its strongest powers to enforce cleanups that would be paid for by polluters instead of taxpayers.”

But there are 15,000 PFAS compounds, according to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. There is nothing to stop companies from trying to play around with other compounds that could also prove harmful. Cleaning up the PFAS chemicals that have already been allowed will take billions of dollars and water utilities around the country are already screaming, with some justification, that the federal government needs to provide more money than it is offering. And even the Superfund designation does not actually ban their use.

It would be better if the United States were to follow the lead of the European Union which is now considering a ban or major restrictions on the whole class of chemicals, fearing that “without taking action, their concentrations will continue to increase, and their toxic and polluting effects will be difficult to reverse.”

The effects are scary to quantify. Regan said in his drinking water announcement that the new rules would improve water quality for 100 million people and “prevent thousands of deaths and reduce tens of thousands of serious illnesses across the country.” A draft EPA economic analysis last year predicted that tight standards could save more than 7,300 lives alone from bladder cancer, kidney cancer and cardiovascular diseases, and avoid another 27,000 non-fatal cases of those diseases.

That makes it high time that the federal government borrow from DuPont’s arrogant assumption that it could push around the EPA. We need the EPA to quickly (like first thing tomorrow) say the following: “Consumer products with PFAS are not safe and are causing unacceptable environmental consequences. We are shutting off the tap on ALL of them.”

Derrick Z. Jackson is a UCS Fellow in climate and energy and the Center for Science and Democracy. Formerly of the Boston Globe and Newsday, Jackson is a Pulitzer Prize and National Headliners finalist, a 2021 Scripps Howard opinion winner, and a respective 11-time, 4-time and 2-time winner from the National Association of Black Journalists, the National Society of Newspaper Columnists, and the Education Writers Association.

Reposted with permission from The Union of Concerned Scientists.

The post After Decades of Disinformation, the U.S. Finally Begins Regulating PFAS Chemicals appeared first on EcoWatch.

“Denying climate change is tantamount to saying you don’t believe in gravity.”

— Christina Figueres, climate advocate and diplomat,

in her 2020 book The Future We Choose

How do we know that the climate is changing — and that humans are causing it? To a certain extent, we can see and feel it ourselves. New temperature and weather extremes are undeniable, and affect more and more places every year. And the greenhouse effect (the mechanism by which carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases trap heat in the Earth’s atmosphere) is taught in many basic science classes. But when asked how they know that “climate change is real,” some people will respond simply that 99.9 percent of scientists agree that it is.

“For me, intellectually, that always felt like a little bit of a cop-out,” said Jesse Nichols, a video producer at Grist. Sure, it’s a compelling statistic, and there’s nothing wrong with putting our faith in the consensus of the scientific community. But Nichols also felt that understanding how scientists have come to this conclusion and supported it — sometimes in surprising ways — can be enlightening, and empowering.

“Something that always has really fascinated me is people who are able to uncover giant stories from tiny little pieces of evidence,” he said, “like environmental detective stories.”

That’s a large part of the ethos behind Proof of Concept, a video series created by Nichols that profiles the science and scientists behind some of the most surprising recent environmental research and discoveries. The videos take viewers from a lab at MIT to a primate research center in California to a museum basement in Seattle stocked with jars of centuries-old preserved fishes.

In one, Nichols interviews scientists studying one of the world’s healthiest coral reefs — the Flower Garden Banks, in the Gulf of Mexico, which also happens to be surrounded by offshore oil drilling.

Like trees, corals grow bands every year that enable researchers to date them — and to gain insight into what was going on in the ocean climate each year that the corals were growing. As Nichols says in his narration: “The legacy of oil extraction, carbon emissions, and climate change are quite literally etched on the hard skeletons of the corals themselves.”

These coral “time capsules,” as one scientist puts it in the video, are exactly the kinds of clues that Nichols was referencing when he likened scientific discovery to a detective story. By analyzing small scrapes of coral from each of the different bands, scientists have been able to track changes over time that align with world events. By looking at the carbon contained in the coral, they could see an increase in an isotope that’s associated with fossil fuel emissions — a clear sign that our planet’s rising carbon emissions are indeed caused by humans. Another finding was the increased presence of barium in the reef skeleton, an element that is often used as a lubricant in offshore oil wells.

“By analyzing the dust that you got from that coral skeleton, you could show that climate change was happening — or that oil had spiked in the Gulf of Mexico in the 1970s, or that fertilizer had been increasing from the Mississippi River, or that nuclear weapons testing had been happening throughout the Cold War,” Nichols said. “All of these world history events were visible inside the skeleton of a coral, and I thought it was so cool that scientists could tell such big stories from such tiny pieces of evidence.”

![]()

In another video from the series, Nichols talks with Chelsea Wood, a parasitologist. “I don’t think anyone is born a parasitologist — like, no one grows up wanting to study worms,” Wood jokes in the video. But when she learned about how biodiverse parasites in fact are, and the often crucial roles they play in ecosystems, it felt like she had discovered a whole new secret world. She decided to devote her career to studying parasite ecology, and how humans are impacting it.

Wood wanted to find out what had been happening in the world of parasites over the past 100 years of global change, and that data didn’t exist. So she figured out a way to get it. Much like the scientists at Flower Garden Banks used the historical record preserved in corals themselves to study how environmental changes have affected reefs, Wood found a historical record of parasites — in the bellies of fishes. She opened up jars of fish samples in the Burke Museum in Seattle dating back to the 1800s and dissected the fish to find out what kinds of parasites were living inside them.

“Chelsea was uncovering a completely overlooked story about how parasites were changing over the last century, using these fish samples that were collecting dust in a basement,” Nichols told me. One thing she and her team discovered is that complex parasites — ones that depend on biodiverse ecosystems with several different host species — have been steadily declining, and climate change is almost certainly the culprit.

![]()

The third follows Lisa Miller, a researcher at the California National Primate Research Center. In 2008, summer wildfires were blanketing Northern California with smoke — and Miller had an idea. A group of 50 rhesus monkeys had just been born at the center and, like everybody else in the area, they were exposed to the unusually high levels of wildfire smoke. She wondered if they could study these monkeys, compared with a control group born the next year, to learn more about the effects of early exposure to air pollution.

The scientists monitored the monkeys’ health through routine medical examinations like blood draws and CT scans, and also by equipping them with Fitbit-esque collars to monitor their physical activity. They found that the wildfire smoke led to lifelong health impacts. The exposed monkeys had weaker immune systems when they were young, which then turned to overactive immune systems when they were adults. They developed smaller and stiffer lungs than the control group, and didn’t sleep as well.

Because rhesus monkeys are genetically similar to humans, these findings have implications for human health as well. Long-term health studies in humans are notoriously difficult, because it’s all but impossible to control different environmental and lifestyle factors that complicate things. But the wildfire smoke that descended over the primate research center, a completely controlled environment, offered a unique opportunity to learn more about this climate impact.

“It really was, in my view, serendipity — in the sense that we were at the right place at the right time,” Miller says in the video.

![]()

The fourth and final video in this year’s series will publish tomorrow. Check out grist.org/video to watch it then!

As a sneak peek: The story looks at ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase, or RuBisCO — an enzyme that enables plants to pull carbon dioxide from the air to support photosynthesis, a process that in turn fuels all life on Earth. The twist is that RuBisCO is notoriously bad at its job, and climate change appears to be making it even worse. But scientists are working to engineer a new variety.

“I think that science in itself helps us know how the world works, and you can’t solve a problem if you don’t know how the system works,” Nichols said. “All of these are stories of people who are trying to get a clearer picture of what’s going on. And having a good picture of what’s going on, it’s kind of like having a map when you’re lost in the wilderness.”

— Claire Elise Thompson

In last week’s newsletter about the 15-minute city, we asked what you can walk to within 15 minutes of where you live. For fun, I put some of your answers into an AI image generator to see what our collective 15-minute city could look like. One thing I found interesting — even with my prompts, the generator struggled to conjure up a “city” without cars, and to fit many different specific features (a pizzeria, a taco truck, a bookshop, a church, an urgent care clinic …) into a single scene. But I’d still live here, I think. What about you?

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How tiny pieces of evidence can reveal giant stories about our world — and ways to make it better on May 15, 2024.