All of our clothing has an environmental impact and that includes our beloved jeans. On…

The post We Earthlings: Make Your Jeans Last appeared first on Earth911.

All of our clothing has an environmental impact and that includes our beloved jeans. On…

The post We Earthlings: Make Your Jeans Last appeared first on Earth911.

Jera Slaughter looks at her backyard with pride, pointing out every feature and explaining how it came to be. The landscaping committee in her apartment building takes such things seriously. But unlike homeowners who might discuss their prized plants or custom decking, Slaughter is describing a beach, one covered in large concrete blocks, gravel, and a small sliver of sandy shoreline that overlooks Lake Michigan. It’s a view worthy of a grand apartment building built on Chicago’s South Side in the 1920s and deemed a national historic landmark.

But repeated flooding has over the years radically remade the private beach. Slaughter has lived in the Windy City long enough to remember when it extended 300 feet. Now it barely reaches 50. Her neighborhood might not be the first place anyone would think of when it comes to climate-related flooding, but Slaughter and her neighbors have been witnesses to a rapid erosion of their beloved shoreline.

“Out there where that pillar is,” she said, pointing to a post about 500 feet away, “that was our sandy beach. The erosion has eaten it away and left us with this. We tried one year to re-sand it. We bought sand and flew it in. But by the end of the season, there was no sand left.”

Recent years have seen high lake levels flood parking garages and apartments, wash out beaches, and even cause massive sinkholes. It’s a growing hazard, one that Slaughter has been desperately fighting for years.

“All things considered, this is our home,” she said.

Lake Michigan has long tried to take back the land on its shores. But climate change has increased the amount of ground lost to increasingly variable lake levels and ever more intense storms. What was once a tedious but manageable issue is now a crisis. The problem became particularly acute in early 2020 when a storm wreaked havoc on the neighborhood, severely damaging homes, flooding streets, and spurring neighbors to demand that City Hall support a $5 million plan to hold back the water.

“We need to be prepared for higher lake levels,” said Charles Shabica, a geologist and professor emeritus at Northeastern Illinois University.

Though Shabica says the erosion in the Great Lakes region won’t be on par with what rising seas will bring to coastal regions, he still notes it’s an issue that Chicago must prepare for.

“We’ll see climate impacts, but I think we can accommodate them,” said Shabica.

Beyond flooding homes, that epic storm opened sinkholes and washed out certain beaches, leaving them eroded and largely unusable. But the people of South Shore refused to give in easily. In the wake of Lake Michigan’s encroaching water, residents have organized their neighbors and prompted solutions by creating a voice so loud that politicians, engineers, and bureaucrats took heed. In 2022, state Representative Curtis Tarver II helped secure $5 million from the state of Illinois to help solve the issue.

“For some odd reason, and I tend to believe it is the demographics of the individuals who live in that area, it has not been a priority, for the city, the state, or the [federal government],” Tarver said.

After years of tireless work, folks in this community have convinced the city to study the problem of lakeside erosion to see how bad this damage from climate change will be — and how fast they can fix it.

Slaughter founded the South Side Lakefront Erosion Task Force alongside Juliet Dervin and Sharon Louis in 2019 after a few particularly harsh fall storms caused heavy flooding in the area.

Chicagoans in the predominantly Black and middle-class South Shore had noticed the inequitable treatment of city shoreline restoration projects. Beaches in the overwhelmingly white and affluent North Side neighborhoods received more media coverage of the problem, faster fixes, and better upkeep, according to the group. This disparity occurred despite the fact that South Side beaches have no natural barriers to the lake’s waves and tides, placing them at greater risk of erosion.

“We were watching the news coverage [of] what was happening up north as if we weren’t getting hit with water on the south end of the city,” said Louis.

The threat is undeniable to Leroy Newsom, who has lived in his South Side apartment for 12 years. Despite the fact that another building stands between his home and the lake, he and his neighbors often experience flooding. The white paint in the lobby is mottled with spackle from earlier repairs. During particularly intense deluges, the entryway can become unnavigable. A large storm hit the city on the first weekend in July, inundating several parts of the city and suburbs.

“When we get a rainstorm like we did before, it floods,” he said.

Newsom lives on an upper floor and has not had to deal with the particulars of cleaning up after flooding, but he has noticed it is a persistent issue in the neighborhood.

Louis, Dervin, and Slaughter have spent countless hours tirelessly knocking on doors and even setting up shop near the local grocery store to teach their neighbors about lake-related flooding. They wanted to mobilize people so they could direct attention and money toward solving the issue. They also researched the slew of solutions available to stem the tide of the lake.

“People were making disaster plans, like, ‘What if something happens, this is what we’re gonna do’. And we were looking for mitigation plans, you know. Let’s get out in front of this,” said Louis.

Solutions can look different depending upon the area, but most on the South Side mirror the tools engineers have used for years to keep the lake at bay elsewhere. What makes these approaches a challenge is how exposed the community is to Lake Michigan in contrast to other neighborhoods.

“South Shore is uniquely vulnerable,” said Malcolm Mossman of the Delta Institute, a nonprofit focusing on environmental issues in the Midwest. “It’s had a lot of impacts over the last century, plus, certain sections of it have even been washed out.”

The shoreline throughout the city is dotted with concrete steps, or revetements, and piers that extend into the lake to prevent waves from slamming into beaches. It also has breakwaters, which run parallel to the shoreline and are considered one of the best defenses against an increasingly active Lake Michigan.

“The best solution that we’ve learned are the shore parallel breakwaters,” said Shabica. “And we make them out of rocks large enough that the waves can’t throw them around. And the really cool part is it makes wonderful fish habitat and wildlife habitat. So we’re really improving the ecosystem, as well as making the shoreline inland a lot less vulnerable.”

Shabica also mentions that this isn’t a new solution. The Museum Campus portion of the city, which extends into the lake and includes the Field Museum, the Shedd Aquarium, and the Adler Planetarium, used to be an island before engineers decided to connect it to the shoreline in 1938.

The main component of the plan to help reduce repeated flooding in the neighborhood is to install a breakwater around 73rd Street using the funding Tarver helped earmark for the issue, according to Task Force co-founder Juliet Dervin. This solution would help prevent the types of waves and flooding that damage streets, most notably South Shore Drive, which is the extension of DuSable Lake Shore Drive. Past damage to the streets has rerouted city buses that run along South Shore Drive and interrupted the flow of traffic.

One local resident installed a private breakwater at her own expense following the 2020 storm, just a few blocks from Slaughter’s house, and it has tempered some effects of intense storms and flooding. But since this breakwater is smaller, surrounding areas are still vulnerable. Breakwaters can range from a few hundred thousand dollars to millions of dollars, depending on size and other factors.

Despite funding now being allocated to fix the issue and government attention squarely focused on lakefront-related flooding there are still hurdles to overcome.

Both the Army Corps of Engineers and the Chicago Park District are in the middle of a three-year assessment of the shoreline to determine appropriate fixes for each area. The study will finish in 2025, decades after the last study of this kind was conducted in the early 1990s. This gives Slaughter pause.

“If I tell you this continuous erosion has been going on for such a long time, then you would have to know, they have looked into it and studied it from A to Z,” she said. “What do you mean, you don’t have enough statistics? We’ve done flyovers and all kinds of things. People who’ve been here filming it, when the water jumps up to the top of the building, they’ve seen it slam into things.”

For her, the damage has been clear but the prolonged period of inaction and lack of attention from outside groups means a shorter window to implement fixes. Slaughter sees this as a fundamental flaw in how we approach issues stemming from the climate crisis.

“The philosophy,” she said, “is repair, not prevent.”

This story was updated to give the correct year in which $5 million was secured from the state of Illinois to address the erosion.

This piece is part of a collaboration that includes the Institute for Nonprofit News, Borderless, Ensia, Planet Detroit, Sahan Journal, and Wisconsin Watch, as well as the Guardian and Inside Climate News. The project was supported by the Joyce Foundation.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline On Chicago’s South Side, neighbors fight to keep Lake Michigan at bay on Aug 8, 2023.

This story is part of Record High, a Grist series examining extreme heat and its impact on how — and where — we live.

When Donna Crawford didn’t hear back from her brother Lyle, she began to fear the worst. It was Monday, June 28, 2021, at the tail end of a blistering heat dome that had settled over the Pacific Northwest. Two days prior, daytime temperatures had soared to 108 degrees Fahrenheit in Gresham, Oregon, where Lyle lived alone in the small yellow house the siblings had grown up in. “I hope you’re doing OK in the heat,” she had said into his answering machine that day.

By the time Donna contacted the police, Lyle had already died alone in his house; a box fan was found swirling oven-hot air nearby. He was 62 years old.

Lyle lived for most of his life in Gresham, a suburb outside Portland, spending his time hiking through the mountains and rivers of Oregon and caring for his mother before her death. Although he was friendly and enjoyed chatting with his barber and other acquaintances, he had few friends later in life and grew even more isolated during the pandemic. Donna, his only remaining family, lived 3,000 miles away in Richmond, Virginia.

“He would have answered the door if someone knocked, and that might have done it. An actual human being,” Donna told county health officials. “But how can there be enough human beings to go to the door of every older person?” Lyle was one of at least 48 people living alone who died in Multnomah County, which includes Gresham and Portland, during the heat wave.

In May, the U.S. Surgeon General issued a warning that Americans are experiencing an “epidemic of loneliness and isolation.” The report lays out a worrying array of statistics showing that people are less socially connected than ever before. In 2021, almost half of Americans reported having fewer than four close friends, while only a quarter said the same in 1990. U.S. residents spent 24 more hours per month alone in 2020 than they did in 2003. Only 3 in 10 Americans know most of their neighbors. And people living alone now make up 29 percent of U.S. households, compared to 13 percent in 1960.

The isolation crisis is compounding the dangers of deadly heat waves fueled by climate change. In the U.S. and many other countries, social isolation is a major risk factor for dying during a heat wave. Experts say that isolation is made worse by a shortage of social infrastructure like libraries, local businesses, green spaces, and public transit, leaving people who are older and live in disinvested neighborhoods most at risk from extreme heat. As heat waves become more frequent, cities are exploring strategies to build social connections and reach isolated individuals before it’s too late.

“We talk a lot about the emerging climate crisis, but far less about the social infrastructure crisis,” Eric Klinenberg, a sociology professor at New York University, told Grist.

In the U.S., up to 20,000 people died of heat-related causes between 2008 and 2017. At scorching temperatures, people can experience heat exhaustion, a condition that causes heavy sweating, nausea, and fainting. If left untreated, it can lead to heat stroke, a potentially fatal illness that causes delirium, a rapid heart rate, and eventually organ damage and shutdown. Many heat deaths are also caused by heart attacks and other cardiovascular issues made far more likely by exposure to extreme heat.

Klinenberg and other experts stress that all heat-related deaths are preventable, including those that happen when a person is alone. During a heatwave, it’s possible to check in on neighbors and bring people air conditioning units or help move them to cooling centers. Analogous life-saving measures aren’t always possible during other extreme weather events, like hurricanes or floods.

“There’s been a long understanding of how heat affects your body and a long understanding of a range of interventions to get your core body temperature back down,” Kristie Ebi, a global health professor studying the impacts of climate change at the University of Washington, told Grist. “People don’t have to die.”

But without adequate outreach, it can be easy for isolated individuals “to get into trouble with the heat,” Ebi said. That’s because heat accumulates in the body gradually, so even a healthy person may not realize that their core temperature is reaching dangerous levels until it’s too late.

For older adults, the risks of heat and isolation are especially acute. Older people are more likely to experience risk factors that can cause or exacerbate isolation, including living alone, chronic illness, and loss of family and friends. At least a quarter of Americans age 65 and older are considered socially isolated. At the same time, older adults are also more at risk during heat waves because they do not adjust as well as younger people to sudden changes in temperature. They are also more likely to have a chronic illness or take medication that affects their body’s ability to regulate temperature.

Ebi notes that not only does isolation increase the risk of heat — heat can, in turn, increase isolation. Heat exhausts the body’s energy supply and can impact cognitive function, causing symptoms like confusion. Many people already not feeling up for socializing on a typical day due to chronic medical conditions may feel even less able to reach out during a heat wave.

Research has shown that due to sheer proximity, neighbors are among the most effective first responders during a natural disaster. In a well connected neighborhood, where residents trust their neighbors and participate in local activities and groups, people are more likely to share resources and help one another prepare for and recover from disaster events. As a result, communities with robust social networks tend to fare much better during extreme weather like heat waves.

Klinenberg first observed this pattern while studying the social and economic disparities that shaped a devastating 1995 heat wave in Chicago. Over the course of five days, more than 700 people died as temperatures climbed up to 106 degrees Fahrenheit. Residents who were poor, Black, and older died at disproportionately high rates. When comparing neighborhoods with similar levels of income and people living alone, he found that far fewer deaths happened in communities that were better connected than in more isolated areas.

One aspect those neighborhoods had in common was an abundance of social infrastructure, or the physical places that enable interaction, Klinenberg found. It can be something as simple as a stoop or a park bench to pause on. At a larger scale, social infrastructure can look like a bustling sidewalk, a community garden, the subway, or a local library — anything that “gives people a place to gather and draws people out of their homes into contact with neighbors,” Klinenberg said.

“The people who lived in depleted neighborhoods, places that had lost their social infrastructure, were far more likely to die alone than people who lived in neighborhoods with a rich social infrastructure,” he said — “for the simple reason that you’re more likely to wind up home alone.”

In Chicago and elsewhere in the U.S., access to those public spaces is highly unequal, owing to decades of disinvestment in historically redlined neighborhoods and other low-income communities. As a result of racist housing, lending, and transportation policies, predominantly Black communities and communities of color disproportionately live in neighborhoods that lack adequate housing, schools, transportation, parks, and other essential infrastructure. Previously redlined neighborhoods also tend to experience hotter temperatures due to the urban heat island effect, where a lack of green spaces and more paved roads and buildings lock in heat and raise temperatures up to 12.8 degrees Fahrenheit higher than non-redlined areas.

These inequalities have fatal consequences. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Indigenous people and Black people had the highest rates of heat-related deaths in the U.S. between 2004 and 2018. In New York City, local officials reported that the heat-related death rate among Black people from 2011 to 2020 was more than twice as high as that of their white counterparts.

Bharat Venkat, a professor of society and genetics at UCLA and director of the UCLA Heat Lab, said the issue of infrastructure is just one way in which extreme heat lays bare the dangers of existing inequities.

“Those vulnerabilities are ones that are produced socially and politically,” he said. “And that’s what makes the heatwave so deadly and dangerous.”

Recognizing the risks of isolation, many cities have ramped up community outreach during heat waves. As part of early warning systems, cities like Baltimore, Chicago, and Philadelphia send out text alerts, connect with community and faith-based organizations, and conduct on-the-ground outreach to at-risk populations. Phoenix, Miami, and Los Angeles have gone a step further by appointing chief heat officers to coordinate citywide responses to heat emergencies. Those plans include measures like distributing maps to cooling centers and water bottles, calling residents directly, and raising awareness of heat risks through broadcasting on television, radio, social media, and billboard ads.

In Philadelphia, 6,000 volunteer “block captains” serve as neighborhood leaders for residential blocks ranging from as few as four households to as many as 99 households. The initiative, which was created primarily to lead street clean-up efforts, has also proven an effective way of reaching residents during heat emergencies, according to Dawn Woods, administrator of the program. Block captains receive information on city services and resources from the city’s Office of Emergency Management and help share knowledge by hosting block meetings and connecting with folks one-on-one.

“For neighbors who are sick or can’t leave their home, we ask block captains to just constantly check in on them and make sure that they have phone numbers on hand, so that they can reach out to somebody in the event of an emergency,” Woods told Grist.

Klinenberg and Venkat said that although community outreach is important, cities should also work to address the broader issues that deepen isolation and heat risk. That includes addressing a national shortage of affordable housing that leaves more people unsheltered, less able to access cooling and community resources, and at greater risk of dying during a heat wave. It also means investing in neighborhoods to build and maintain the local businesses and public facilities that give people the chance to connect with their neighbors.

Venkat pointed to other pressing needs, such as making energy costs more affordable so that people don’t have to choose between putting food on the table and running air conditioning. Another is ensuring rights to cooling for renters and people living in public housing. In Phoenix, for example, a city ordinance requires landlords to provide air conditioning or other cooling systems for rental units. Venkat said cities should also step up efforts to plant trees in neighborhoods that lack green spaces, which provide vital shade and cooling in places where asphalt and concrete trap heat.

“It’s not that people die from heat waves,” Venkat said. “What they die from are social and political decisions about how we govern and take care of people.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline A crisis of isolation is making heat waves more deadly on Aug 8, 2023.

This story was co-published with WBUR.

As heavy rain drenched Barre, Vermont, last month, Kim Beinin was watching Thor with her two young children. About halfway through the movie, she peeked out the window and was startled to see water flowing over the road and into her neighbor’s driveway. Knowing her home was surely next, she gathered her children and fled.

When the rain stopped two days later, she returned to find her basement submerged in 5 feet of water. The heating oil tank lay on its side, the water heater was flooded, and the electrical panel had cut out, leaving the house without power.

“It was horrific,” she said. “My contractor was like, ‘I cannot believe your garage is still standing.’” The shock of seeing her house waterlogged was made worse by the fact that Beinin felt blindsided. “I was told I wasn’t in a flood zone.”

The most common reference for flood risk are the flood insurance rate maps, also known as 100-year floodplain maps, that the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, produces. They designate so-called special flood hazard areas that have a roughly 1 percent chance of inundation in any given year. Properties within those zones are subject to more stringent building codes and regulations that, among other things, require anyone with a government-backed mortgage to carry flood insurance.

The property information report that sellers include with most home sales in Vermont indicates whether a property is in a flood zone. But Beinin says she received no such warning because FEMA indicated that the house she bought in 2021 was well outside a high-risk area. Yet the entire area was walloped. The torrent washed away her neighbor’s driveway and left their garage broken, tilted, and cracked. A red “DANGER UNSAFE” poster remains plastered on the front of it.

Although the federal maps “can help communicate risk,” they’re often incomplete or outdated and don’t adequately reflect the threat, especially as the climate changes, said Chad Berginnis. He is the executive director of the nonprofit Association of State Floodplain Managers and also a member of FEMA’s National Advisory Council. Other experts echoed his opinion that FEMA’s assessments “are a good place to start but should never be the end point in knowing flood risk.”

When the nonprofit climate research firm First Street Foundation compared its flood model to FEMA’s maps, the report found that as of 2020 5.9 million properties and property owners are currently unaware of or are underestimating the risk they face, because they are not identified as being within the special flood hazard areas zone. The small creek running past Beinin’s home wasn’t shown as flood-prone on the federal map, but First Street’s model included it and rated the property an “extreme flood risk.” Had she known that, she said, “I either would have gotten flood insurance or maybe not bought the house.”

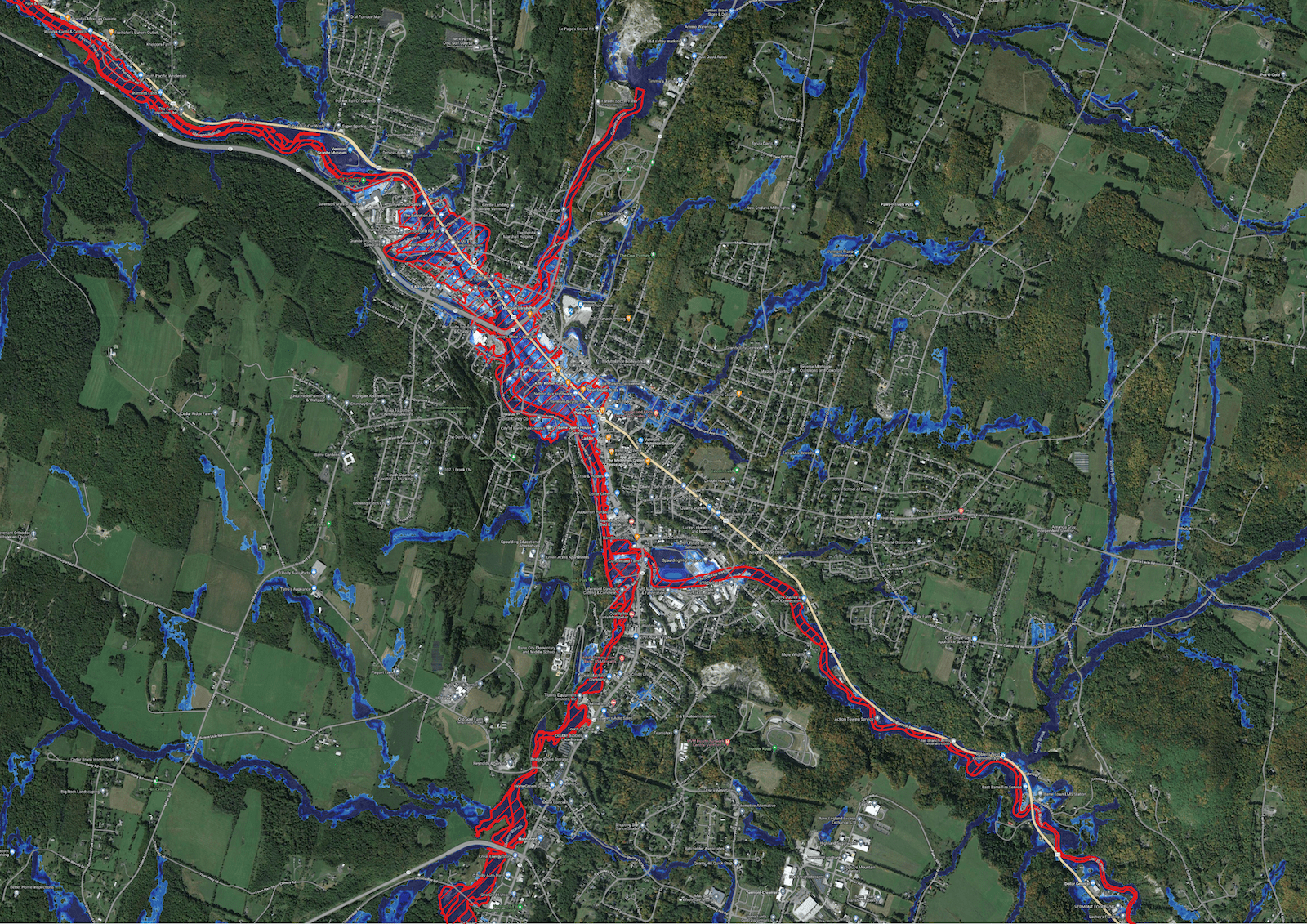

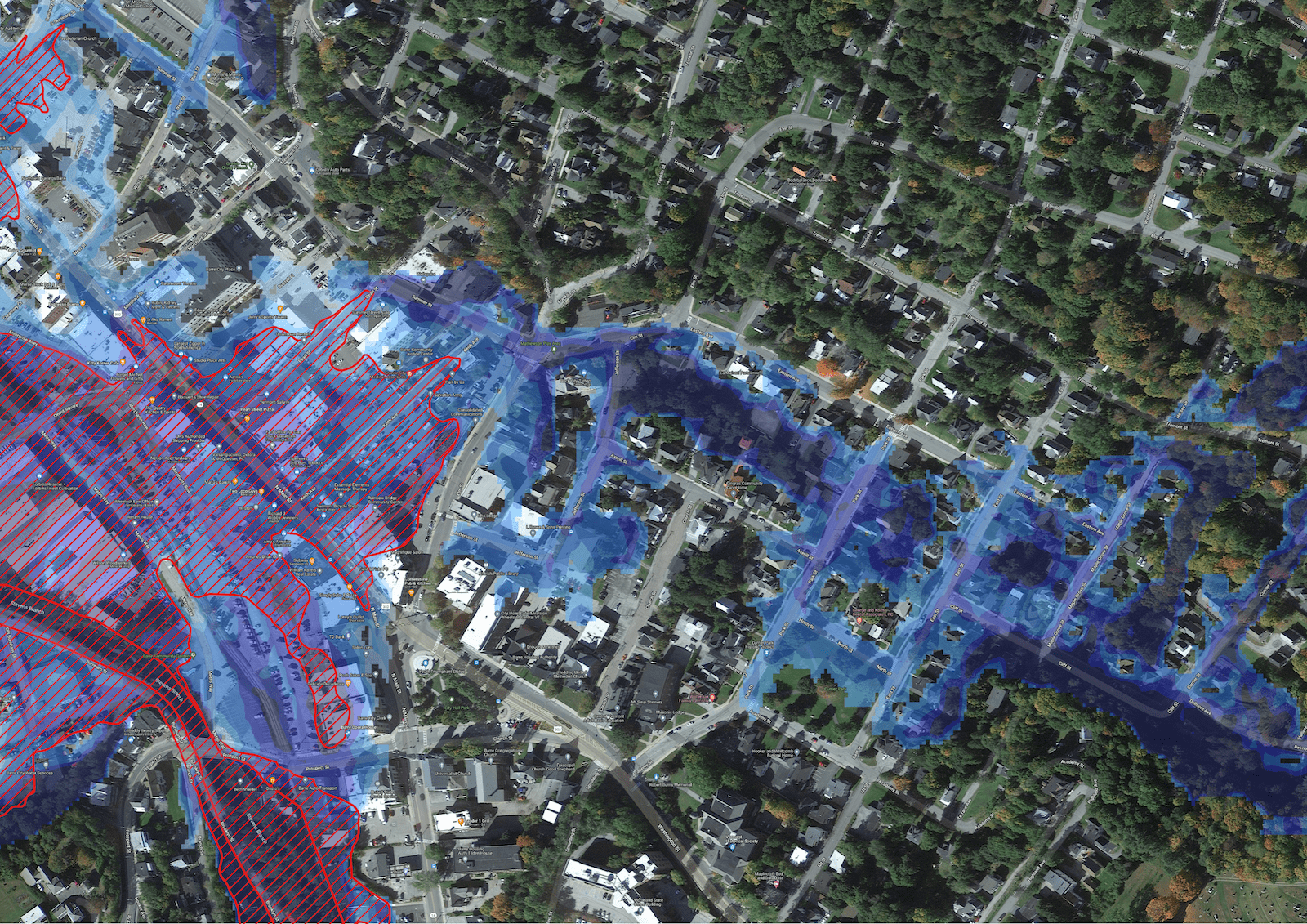

Satellite maps of Barre, Vermont, show FEMA’s 100-year-flood zone in red. First street Foundation’s analysis found a much larger 100-year-flood zone, as marked in blue. First Street Foundation

According to FEMA, its maps aren’t meant to predict where a flood might occur, or even where they have occurred in the past. Rather, they are “snapshots in time of risk” that are used for flood insurance determinations and managing development in floodplains.

“The flood maps are minimums. They are not a comprehensive understanding of all the flood hazards and flood risks,” said Luis Rodriguez, director of the agency’s engineering and modeling division. “Where it can rain, it can flood.”

But Berginnis says that narrow view reflects a bit of wishful thinking. “Because it is the big national dataset for flood mapping, the way the public often perceives the maps is that they’re the end-all, be-all of flood risk,” he said. “That sort of comes with the territory.”

Regardless, people in FEMA’s blindspots are pummeled at an alarming rate. After Hurricane Harvey hit the Gulf Coast of Texas in 2017, the Harris County Flood Control District, which includes the city of Houston, found that half of the 204,000 homes that flooded were outside the federal hazard zone. According to FEMA, 40 percent of claims made through its National Flood Insurance Program come from people beyond the 100-year floodplain.

Cambridge, about an hour from Barre, is another area of Vermont where FEMA maps failed to adequately capture the risks residents face.

“I would say the FEMA maps are grossly outdated,” said Jonathan DeLaBruere, the town administrator. Cambridge’s map isn’t even fully digitized, so he has a scan pulled up on his computer and pointed to the date in the corner: 1983.

The high-risk floodplain is marked in gray and weaves up from the Lamoille River toward Main Street. A handful of properties are included in FEMA’s 100-year floodplain, but most aren’t. Regardless of their designation, almost all of the buildings have flooded multiple times in the last century.

Pearl Dennis bought her house, which isn’t in a FEMA hazard area, in 2015. It only took a few years before flood waters reached her front steps. “We tried to get flood insurance after the 2019 flood,” she said. “We were denied because we were too far away from the river.”

FEMA said it cannot comment on specific cases for privacy reasons, but in an email to Grist an agency spokesperson said the distance to a river or other body of water does not impact federal flood insurance eligibility. He also said National Flood Insurance Program policies are available for “any eligible building” in a community that participates in the program, as both Barre and Cambridge do.

This month’s storm sent the Lamoille raging through the first floor of Dennis’ house, flooding her basement and backyard along the way. Hay bales weighing 600 pounds floated over from a neighbor’s farm and still sit on the lawn. Her floorboards are peeling, and the street is piled with ruined appliances, belongings, and debris.

Similar stories and sights abound on the block, even though large swaths of the waterlogged street lie in an area that FEMA says should flood less than every 500 years.

“The word ‘flood’ never came up at all until July 10,” said Erica Hayes, whose parents bought the Cambridge Market Village earlier this year. Then they saw 9 feet of water inundate their basement. While First Street pegged the store as a “moderate” flood risk, FEMA does not include it in its hazard area.

“If we were in a flood zone, we probably wouldn’t have bought,” said Hayes. The store didn’t have flood insurance, because it wasn’t mandatory and the cost proved prohibitive. Hayes pegs the damage at roughly a quarter million dollars.

“We have to cover it out of pocket,” she said. “But there’s no pocket to pay out of.”

One of the problems Berginnis noted is that FEMA has mapped only about a third of the nation’s streams, rivers, and coastlines.There are other faults as well. Many maps are decades out of date, despite a statutory requirement that FEMA review them every five years. They also do not capture urban stormwater flooding caused by intense rain — events that Berginnis say are becoming more frequent and intense.

That points to what may be the biggest shortcoming of all: The maps don’t account for climate change, because they rely on historical rather than forecasted data. In 2012, Congress told FEMA to incorporate future conditions such as sea-level rise, but more than a decade later, that hasn’t happened.

“If FEMA did what Congress directed it to do, it would probably smooth out a lot of things,” said Rob Moore, the director of the Water & Climate Team at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

The delay in integrating climate data stems in part from the Trump administration, said FEMA spokesperson Jeremy Edwards. “Under the previous administration, climate resilience was not a priority,” he said, which limited what could be done. Now, he said, it’s a top concern. The agency is “working toward” incorporating future conditions into its maps, especially sea-level rise, Rodriguez said. That data should be available by the end of the 2025 fiscal year.

But inland flood risk is more challenging to model, Rodriguez said, and the science “is just not evolved enough to be able to credibly provide information around future conditions.” More broadly, FEMA’s Future of Flood Risk Data initiative aims to adopt a graduated analysis of risk rather than the binary “in” or “out” approach that currently exists with regard to flood zones.

In the meantime, Rodiquez says roughly 84 percent of FEMA’s maps are “current and updated,” which exceeds the agency’s goal of 80 percent. As for the remaining areas, he said, “resources are certainly a consideration. We have to prioritize.” The focus has been on those areas at highest risk, often places with large populations. But, he added, “communities can make requests to FEMA to update that flood hazard information“ at any time.

While the maps are lagging behind, FEMA has in recent years modernized its model for setting insurance rates. The revamped system, called Risk Rating 2.0, uses many inputs in addition to maps, including private data from contractors such as CoreLogic and Atkins. But this more accurate assessment of risk is only accessible through an insurance company or agent.

First Street has made its model publicly available at riskfactor.com, where anyone can type in an address and receive user-friendly risk information for any property in the U.S. Redfin and Realtor.com have also incorporated the data. It tries to improve on FEMA’s work by, among other things, covering the entire country, taking climate change into account, and incorporating rain and other precipitation hazards.

Many states and municipalities have undertaken their own mapping efforts. Since 2000, Mecklenburg County and the city of Charlotte, North Carolina, have been including current and future floodplains on its official maps. The Harris County Flood District has worked with FEMA to update its maps, which when released later this year will be the first in the nation to incorporate urban stormwater flooding.

“This update is really a transformational way of thinking about floodplains,” Tina Petersen, the executive director of the district, told the Houston Chronicle. The size of the floodplain will also increase by about a third.

Vermont’s effort to improve on federal maps began in the early 2000s. “We came to realize that so much of our flood risk is due to flood-related erosion,” said Rob Evans, manager of Vermont’s River Program. “[But] the FEMA maps really don’t capture river dynamics at all.”

The state set out to chart where rivers should, or would, go during a flood. “This is the minimum space the river needs to be least erosive,” Evans explained. Sometimes these so-called ”river corridor” maps overlap with federal flood zones, but often they are significantly more expansive. The state, for instance, captured the potential for flooding on Beinin’s property that FEMA did not.

“We have a number of towns that have adopted river corridors into their zoning,” said Evans, and so has the state. That means river corridors must be taken into account when planning construction and setting building standards.

That said, Vermont maps aren’t as well known or ingrained in policy as FEMA’s (Beinin and other flood victims Grist interviewed didn’t know about them). That’s another reason it’s critical that FEMA finish mapping the whole country, a project Berginnis’ group estimates will cost between $3.2 billion and $11.8 billion.

“When you think about the damages that you might be able to avoid with better mapping,” Berginnis said, “that investment is totally worth it.”

But even the most advanced flood models are still evolving. Landslides, for example, are one hazard that most of them don’t include, said Beverly Wemple, a professor of geography and geosciences at the University of Vermont. A rain-induced landslide tore a home off its foundation not far from Beinin’s house. The same thing happened to another house an hour south in Ripton.

“We don’t have an approach to capturing flood impacts in mountainous terrain,” said Wemple. “They are hugely vulnerable to damage”

Berginnis has seen some signs that federal flood maps may improve in coming years. Last year’s bipartisan infrastructure bill included $492 million to update the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration precipitation database that underlays much of FEMA’s work in this area. But he said more can and should be done.

“Why are we so addicted to spending on disaster recovery, rather than investing in disaster prevention?” he asked. “We don’t have that same urgency.“

This story has been updated with additional information from FEMA about National Flood Insurance Program eligibility.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline FEMA maps said they weren’t in a flood zone. Then came the rain. on Aug 8, 2023.

Kaliko is excited to get her day in court.

The 13-year-old is one of 14 Hawaiʻi youth suing the state Department of Transportation over its role in promoting greenhouse gas emissions that are warming the planet. A circuit court judge ruled Thursday that the trial will start June 24 in Honolulu’s environmental court.

“I can see every day how climate change is affecting everyone’s life and has significantly affected mine as well,” Kaliko said in an interview Monday. She is identified by her first name only in court documents due to her age.

Kaliko was calling from her home in west Maui, where she was holding two ice packs on her head to keep cool in Monday’s sweltering heat as her chickens hid in the shade of a pine tree. The teenager worried how a hotter world will make it harder for her to do the things she loves, like biking, surfing, and gardening.

“I joined this case so nobody would have to experience what I have experienced and so I can make the world a better place,” she said.

Five years ago, her family lost its home in Hurricane Olivia. The winds had weakened to a tropical storm by the time they hit her home island of Maui, but the storm still downed power lines and flooded houses. It was the first tropical storm to hit the island in recorded history.

Climate change is not only expected to lead to hotter weather but also more frequent and more powerful storms globally. Children born in 2020 are between two and seven times as likely to experience an extreme weather event compared to people born in 1960.

Like most of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit, Kaliko is Native Hawaiian. A warming world threatens Indigenous cultural practices, like growing taro, that Hawaiians have engaged in for generations. Increasingly scarce water has forced Kaliko’s family to change how it grows the crop so it has enough to make poi, a traditional starch.

Their lawsuit, Nawahine v. the Hawaiʻi Department of Transportation, filed in English and the Hawaiian language, argues that the agency prioritizes transportation projects like highway construction that, according to the suit, “lock in and escalate the use of fossil fuels, rather than projects that mitigate and reduce emissions.”

The Department of Transportation declined to comment.

The case is part of a broader youth-led push to hold governments legally accountable for their role in exacerbating the climate crisis.

A state judge in Montana is expected to rule any day now in Held v. Montana, in which 16 young Montana residents call out the state’s role in promoting the fossil fuel industry. It is the first lawsuit of its kind to reach a trial. The youth argue that the state’s support of fossil fuels violates their right, enshrined in Article II of the state constitution, to a “clean and healthful environment.”

The plaintiffs in both cases are represented by Our Children’s Trust, a nonprofit founded 13 years ago in Oregon to sue on behalf of children’s right to a safe climate. It has filed cases in all 50 states and at the federal level, most without success.

What’s significant about the Hawaiʻi and Montana cases is how far they’ve gotten, said Dan Farber, a law professor and expert in climate litigation at the University of California at Berkeley. The Hawaiʻi case would be only the second to see a trial.

“These cases are really good choices to establish precedents that can be built upon later,” Farber said, adding that the fact the Hawaiʻi case is going to trial could encourage judges in states to allow similar cases to proceed.

Both cases hinge on the right, written into each state’s constitution, to a clean and healthful environment. They also accuse state officials of neglecting their duty to preserve and protect the environment for future generations. But where youth in Montana are calling out their stateʻs enthusiastic promotion of the fossil fuel industry, their peers in Hawaiʻi are zeroing in on car-related emissions because the state has set a goal of achieving net-negative carbon emissions by 2045.

Kylie Wagner Cruz, an attorney at the legal nonprofit Earthjustice, is representing the youth plaintiffs along with Our Children’s Trust. She said she’s confident about her clients’ chances, particularly since the Hawaiʻi Supreme Court has already ruled that the state constitutional right to a clean and healthful environment includes the “right to a life-sustaining climate system.”“We have an opportunity with this case to transform Hawaiʻi’s transportation system to benefit all of Hawaiʻi’s people,” Cruz said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Hawaiʻi’s youth-led climate change lawsuit is going to trial next summer on Aug 7, 2023.

It’s winter in South America, but the temperatures don’t feel like it.

In northern Argentina and Chile, it has felt more like summer, with towns in the Andes mountains heating up to more than 100 degrees Fahrenheit, reported The Conversation.

“South America is living one of the [most] extreme events the world has ever seen,” tweeted weather historian Maximiliano Herrera. “Unbelievable temperatures up to 38.9C in the Chilean Andine areas in mid winter! Much more than what Southern Europe just had in mid summer at the same elevation: This event is rewriting all climatic books.”

The heat wave in the Chilean Andes has been causing snow melt below 9,840 feet, which will be felt in the spring and summer by valley residents downstream, The Guardian reported.

“The main problem is how the high temperatures exacerbate droughts (in eastern Argentina and Uruguay) and accelerate snow melting,” said Raul Cordero, a climatologist at the Netherlands’ University of Groningen, as reported by The Guardian.

Local climate scientists have said the combination of El Niño and human-caused climate change could bring more hot temperatures and extreme weather.

The period from January to July of this year has been one of the warmest ever recorded in South America.

“Tuesday was likely the warmest winter day in northern Chile in 72 years,” Cordero told CNN.

According to Marcos Andrade, director of atmospheric physics at Universidad Mayor de San Andrés, Peru and Bolivia’s Andean plateau has been having “unusual” weather since the beginning of 2023, The Guardian reported.

Cities in Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil have broken heat records.

“With the arrival of the El Niño phenomenon, it is expected that in the coming years this region will suffer an increase in the already high temperatures, making it necessary to take adaptation measures to avoid deaths and greater disasters,” said Karla Beltrán, an environmental consultant, as reported by The Guardian.

Beltrán said the most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report indicated that the southern portion of South America was especially susceptible to heat waves. Periods of abnormally high temperatures are expected to occur more often in the Amazon and other northern parts of the continent, according to some studies.

“Without a doubt, the maximum temperature records in winter in Chile and, to a certain extent, in South America are atypical. High pressure systems are more intense and persistent anomalies in the southern hemisphere, inducing hot air advection and/or directly generating temperature extremes. This high pressure will tend to remain and intensify in the coming decades with climate change,” said Chico Geleira, deputy director of Brazil’s Polar and Climatic Center and a professor of climatology and oceanography at the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, as The Guardian reported.

Africa, Australia and some archipelagos have also been experiencing unseasonably warm temperatures, reported The Washington Post. “Overall, this heatwave is a startling reminder of how humans are changing Earth’s climate. We will continue to see such unprecedented extremes until we stop burning fossil fuels and emitting greenhouse gases into the atmosphere,” Matthew Patterson, postdoctoral research assistant in atmospheric physics at the University of Oxford, wrote in The Conversation.

The post South American Winter Feels Like Summer With Mountain Temperatures Above 100°F appeared first on EcoWatch.

The Open Water Swimming World Cup was canceled in Paris on Sunday after heavy rainfall caused water quality in the Seine to fall below minimum health standards.

“World Aquatics is disappointed that water quality in the Seine has resulted in the cancellation of the World Aquatics Open Water Swimming World Cup, but the health of our athletes must always be our top priority,” said World Aquatics President Husain Al-Musallam, as Swimming World reported.

Swimming events for the 2024 Olympic Games are scheduled to be held in the iconic river, but “extra work” will be needed to make sure alternative arrangements are established, according to the World Aquatics international swimming federation, reported Reuters.

“Disappointed is the right word,” said President of the French Swimming Federation Gilles Sezionale, as Reuters reported. “First and foremost disappointed for the athletes, who were dreaming of competing in one of the most beautiful locations in the world.”

For the past decade, the City of Light has been working to clean up the Seine in order to make it swimmable in time for the Olympics, as well as for the public.

According to the Olympics committee, there will be new infrastructure in place by summer 2024 to improve the river’s water quality, and construction on an $88 billion overflow basin should be finished before the Olympic Games.

“World Aquatics remains excited at the prospect of city-centre Olympic racing for the world’s best open-water swimmers next summer. However, this weekend has demonstrated it is absolutely imperative robust contingency plans are put in place,” al-Musallam said, as reported by The Guardian.

Athletes are still scheduled to compete in the Olympic and Paralympic triathlon test event for the 2024 Olympics in the Seine from August 17 to 20, according to World Triathlon, as Reuters reported.

“In the unlikely event that water quality does not meet the requirement of World Triathlon and public health authorities, a contingency plan is in place which would see the race(s) shifted to a duathlon format,” a statement from World Triathlon said, as reported by Inside the Games. “With a year to go before the Games, the efforts to make the Seine swimmable, led by the State and the City of Paris, continue to significantly improve the quality of the water in the Seine.”

Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo recently announced that public bathing will be allowed in three places along the Seine beginning in 2025, as Time Out reported.

Hopefully the river will also be ready for next year’s Olympic swimming events.

“[I]n recent weeks, water quality in the Seine has regularly reached the levels required for competitions to be held on the dedicated site, demonstrating the significant progress made,” city authorities and Paris 2024 organizers said in a joint statement, reported The Guardian.

According to Paris 2024, water quality in the Seine will be “carefully” monitored leading up to the Olympics, CNN reported.

“One year before the Games, the sanitation dynamic continues with the completion of the most significant work to improve water quality in the coming months, in particular to deal with these exceptional weather events,” Paris 2024 said, as reported by CNN.

The post Seine Water Pollution Leads to Cancellation of Open Water Swimming World Cup appeared first on EcoWatch.

The founder of the national Green Amendments movement, Maya van Rossum, returns to discuss Held…

The post Earth911 Podcast: Maya van Rossum on Held v. Montana and Renewable Energy Lobbying appeared first on Earth911.

Even if you’re not much of a gardener, you are probably aware of the harm…

The post Recognize Invasive Pests to Protect Plants appeared first on Earth911.

E-bikes have been in the news recently for a reason nobody wants: Their batteries are sparking dangerous fires. One conflagration burned down homes and businesses in the Bronx in New York City in March, and another blaze at an e-bike store in Manhattan killed four people in June. Those fires are bringing additional scrutiny and regulation to a mode of transportation that’s been hailed as a promising climate solution. But they are also having an unexpected impact on conversations about the right to repair a bicycle, something generations of bicycle owners have taken for granted.

In recent months, People for Bikes, the national trade organization representing bicycle manufacturers, has reached out to lawmakers and officials in several states to request that e-bikes be exempted from right-to-repair bills. Those bills aim to make it easier for members of the public to access the parts, tools, and information they need to fix their stuff. The industry claims it’s a matter of safety, and that people without the proper training should not attempt to repair e-bikes — especially not the batteries. Instead, manufacturers want to see dead and broken batteries recycled, which is why they recently launched a public education campaign encouraging consumers to do so.

Recycling is a crucial step for dealing with battery waste sustainably. It keeps batteries out of landfills, and it can reduce the need for additional mining of critical battery metals like lithium, cobalt, and nickel. But for the e-bike industry to be sustainable over the long term, e-bikes also need to be repairable, since repair prevents waste and conserves the resources that go into making new stuff. To right-to-repair advocates, the claim that it’s unsafe for consumers to fix them is familiar: Consumer tech companies like Apple have said the same thing about repairing smartphones for years. When it comes to e-bikes, advocates worry that safe battery handling is being used to distract from another problem they say right-to-repair would help solve: Cheap, hard-to-repair e-bikes are flooding into cities around the country. These are the same bikes that sometimes have substandard batteries that experts suspect are at the root of the fire crisis.

“I too want people to go to safe repairers,” Nathan Proctor, who heads the national right-to-repair campaign at the US Public Research Interest Group, told Grist in an email. “But I don’t think monopolizing access helps at all.”

E-bikes are soaring in popularity, and for good reason. These battery-powered bicycles allow people to travel farther and faster than they can using an analog bike. They cost less than cars to buy and to own, take up far less space, and can be parked for free. Compared with gas-powered cars, e-bikes are incredibly climate-friendly: A recent analysis by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory found that the typical e-bike rider emits zero to three grams of carbon dioxide per mile pedaled, compared with 350 grams per mile driven in a crossover SUV. E-bikes also have sustainability and safety advantages over EVs, including smaller batteries that require less lithium mining and pose less of a danger to pedestrians.

But while e-bikes are clearly a sustainable choice compared with driving, many e-bike advocates want to see the industry become a model of affordable, accessible, and environmentally friendly transit. For that to happen, consumers need to be able to repair their e-bikes to ensure they last a long time. In addition to a bicycle frame, wheels, and a battery, e-bikes include various electronic displays and sensors, as well as a motor that powers the pedal-assist system. All of these components can break down and require repairs or replacement.

On battery recycling, the U.S. e-bike industry has made good progress. About five years back, a group of bicycle manufacturers came together to lay the groundwork for an industry-wide battery-recycling program. That program was launched on a pilot scale in late 2021. Less than two years later, it has 54 participating bicycle brands and more than 1,800 retail stores serving as drop-off locations for end-of-life batteries nationwide. (An e-bike battery is considered at the “end of its life” when it no longer holds a charge well, which might occur after as few as two or as many as 10 years of use.)

The e-bike battery-recycling initiative is funded like an escrow program, according to Eric Frederickson of Call2Recycle, the recycling logistics nonprofit that runs it. Participating brands pay a fee into a fund for every e-bike battery they import. Call2Recycle uses those funds to administer the collection, transportation, and recycling of e-bike batteries at several locations around the country. Recycling partners include Canada-based Li-Cycle, which has a battery-recycling hub in Rochester, New York; Redwood Materials, headquartered in northern Nevada; and Cirba Solutions, a battery-logistics company that is expanding into lithium-ion battery recycling. Call2Recycle also trains participating retail shops on how to safely handle the batteries, including identifying any damaged batteries to pack in secure containers.

To date, Frederickson said, the program has recycled nearly 6,000 e-bike batteries, or 37,000 pounds of them. Ash Lovell, the electric bicycle policy and campaign director for People for Bikes, which endorses the program, hopes to see that number grow. In May, People for Bikes launched Hungry for Batteries, a new public education campaign that seeks to raise awareness of how to properly recycle e-bike batteries.

While the recycling program started out with a sustainability focus, as e-bike battery fires in New York City and elsewhere started making national headlines, it became “very much a safety-focused campaign,” Lovell said. “That’s been People for Bikes’ big push over the last few months.”

But those same battery safety concerns are now placing bicycle manufacturers at loggerheads with advocates for independent repair.

In a letter sent to New York Governor Kathy Hochul in December, People for Bikes asked that e-bikes be excluded from the state’s forthcoming digital right-to-repair law, which granted consumers the right to fix a wide range of electronic devices. The letter cited “an unfortunate increase in fires, injuries and deaths attributable to personal e-mobility devices” including e-bikes. Many of these fires, People for Bikes claimed in the letter, “appear to be caused by consumers and others attempting to service these devices themselves,” including tinkering with the batteries at home. Before Hochul signed the right-to-repair bill, it was revised to exempt e-bikes.

Asked for data to back up the claim that e-bike fires were being caused by unauthorized repairs, Lovell said that it was “anecdotal, from folks that are on the ground in New York.” A spokesperson for the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, or CPSC, told Grist that battery fires can be the result of physical, electrical, or thermal damage to the battery, as well as “manufacturing defects.” Last December, the CPSC sent a letter to numerous e-bike manufacturers calling on them to ensure their products comply with voluntary industry safety standards for batteries and other electronic systems.

The CPSC spokesperson declined to comment on the role that e-bike, or e-bike battery, repair might be playing in the recent fires. The New York City Fire Department did not respond to a request for comment.

Though People for Bikes’ letter implied otherwise, the intent of New York’s right-to-repair law was not to give people special tools to pry open their batteries at home. The law stipulates that manufacturers must give independent shops and device owners access to the same parts, tools, and documentation they provide to their authorized repair partners. And when there’s a problem with an e-bike battery, most manufacturers offer consumers one option: replacing it.

“There’s no training on battery repair, that I know of, within the bike industry,” said Ryan Waddell, who recently worked as a lead mechanic at the nonprofit e-bike shop GoodTurnCycles, based in Colorado. “If something happens with a name-brand manufacturer [battery], they’ll usually want the battery shipped back” so it can be replaced.

What New York’s right-to-repair law would have done is increase access to parts, tools, and information that manufacturers only make available to select e-bike dealers. For example, e-bike component manufacturer Bosch produces a diagnostic reader that helps identify components that require a reset or replacement, but you have to be a Bosch-certified repair shop to purchase it. Some manufacturers also offer authorized shops, but not consumers, the ability to do major software updates on their systems. And e-bike brands often only sell components, like the motor controller that manages the amount of voltage going to the motor, to dealers of their choosing.

“There’s huge interest” in fixing e-bikes, said Kyle Wiens, CEO of the online repair guide site iFixit. But outside of manufacturers and specialized shops, “no one knows how.”

Wiens said that in addition to making spare parts and repair guides available, the e-bike industry needs to do a better job designing its products to be repairable. Across the industry, he says, there’s very little standardization in terms of parts. Waddell agreed.

“With e-bikes, nothing’s really standardized,” he said. That means that when a crucial component, like the controller, breaks down, it can be tough to find replacements — especially if that model of e-bike is no longer made.

Right-to-repair laws could also help remediate what several industry observers described as a dismal repair scene for the direct-to-consumer e-bikes being sold online. These bikes tend to be cheaper than those made by industry leading brands like Trek and Rad Power Bikes, and they tend to break down more quickly. These are often the same bikes whose batteries don’t meet industry safety standards and may pose a greater fire risk. John Mathna, who runs the e-bike repair shop Chattanooga Electric Bike Co., says that many online e-bike companies offer “virtually no support” when there’s a problem.

“I’ve never seen a repair manual for any online bike,” Mathna said. “Many independent repair shops won’t touch them.”

Right-to-repair bills won’t solve all of the e-bike industry’s repairability issues, and they won’t end the debate over safe battery repair. But Wiens believes these bills would be a “big help” in terms of forcing out information the public needs to repair their e-bikes.

E-bike riders in Minnesota may soon find out if that’s true: In May, Governor Tim Waltz signed the nation’s broadest right-to-repair bill yet. Unlike in New York, Minnesota’s version of the law, which goes into effect in 2024, does not exempt e-bikes.

Lovell, of People for Bikes, said she believes the bill’s sponsors “weren’t totally aware of the issues of including e-bikes in right to repair,” and that the organization is “speaking to some of the legislators about the issue currently.” Minnesota Representative and bill sponsor Peter Fischer confirmed in an email to Grist that industry advocates reached out to him after the bill became law “asking for an exemption for e-bikes.”

“I did tell the folks I am open to meeting with them and hearing what they had to say,” Fischer said. “This does not mean I would support an exemption for them.”

Wiens, from iFixit, had a stern warning for e-bike manufacturers about attempting to evade compliance with the bill. “If they get a carveout in Minnesota,” he said, “we’ll introduce five bills next year targeting them specifically. It’s unacceptable.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Why e-bike companies are embracing recycling while fighting repair on Aug 7, 2023.