The swarms were so thick they obscured the sun. Mohammed Adan, a farmer in northeastern Kenya, watched the horde of desert locusts first descend in late 2019. He’s been grappling with their legacy ever since.

Adan and 61 other farmers grow tomatoes, mangoes, watermelon, and other crops on Taleh Farm, a 309-acre property outside Garissa, a remote town not far from the Somali border. When the locusts first touched down, Garissa’s villagers resorted to traditional mitigation methods like drumming and banging pots and pans together — anything to make loud noise that might disperse the swarm. Women and children shouted at the descending crush, but their endeavors were largely fruitless.

Billions of ravenous, short-horned grasshoppers alighted, devouring every bit of living plant matter in their path. Between February and June 2020, Taleh Farm was eaten to the ground. Adan’s son, Abubakar Mohamed, who goes by Abu, estimated that the locusts caused $2,000 worth of damage that season — a devastating sum in an area where the average annual salary is below $300.

“We’ve heard about locusts from our fathers and grandfathers,” Adan, who is in his mid-50s, recalled. “But we’ve never had to deal with anything like this ourselves.”

While locust swarms spread across 10 countries over the course of early 2020, Kenya was particularly hard hit — one of the swarms feeding off the country stretched to three times the size of New York City. Three million people across the country, many of them small-scale farmers, were at risk of losing their entire season’s harvest. A legion of international organizations, including the United Nations’ World Food Programme and Food and Agriculture Organization, or FAO, marshaled support in collaboration with Kenya’s Ministry of Agriculture. Throughout the locust invasion, the FAO raised more than $230 million, which allowed it to acquire 155,600 liters of synthetic pesticides that were used to treat nearly 500,000 acres.

To handle ground-spraying operations, the Kenyan government enlisted both its army as well as members of the National Youth Service, a voluntary, government-funded vocational and training organization for young Kenyans. Meanwhile, the FAO contracted charter airline companies to conduct aerial spraying. An issue of apocalyptic scale required all hands on deck.

Farmers like Adan were relieved that the government and aid organizations were stepping in to help. “We wanted those pesticides,” he told Grist. “Otherwise, we would have lost everything.”

But Adan didn’t know at the time that the FAO and other humanitarian groups had procured pesticides that were either already banned in the U.S. and Europe or soon would be. The synthetic pesticides in question — part of a chemical class known as organophosphates that includes chlorpyrifos, fenitrothion, malathion, and fipronil — have been known to cause dizziness, nausea, vomiting, watery eyes, and loss of appetite in humans who come into contact with them. Long-term exposure has been linked to cognitive impairment, psychiatric disorders, and infertility in men.

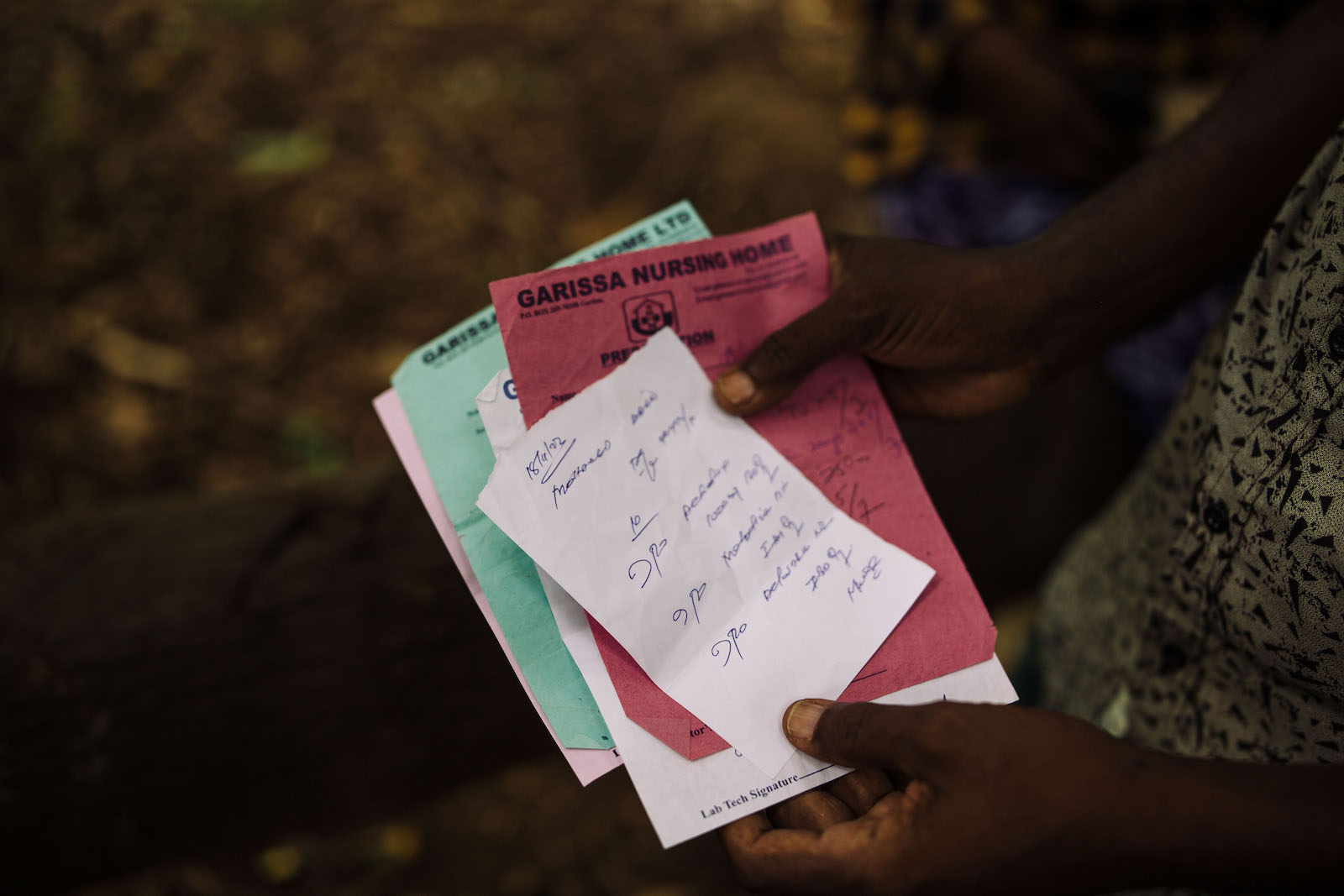

Subsistence farmers in Garissa believe they were accidentally poisoned while using these chemicals — and they’re still dealing with the ramifications. Adan has been suffering from a host of health maladies since 2020, including infertility and incontinence, and he has undergone five surgeries in the last few years.

Kang-Chun Cheng

Kang-Chun Cheng

Internal FAO documents show that the agency was aware of widespread environmental and public health problems that resulted from its distribution of pesticides. The agency’s own assessment found that the toxic chemicals were handed to farmers without any protective equipment, such as gloves and coveralls, or adequate training on how to use them safely. Christian Pantenius, a former FAO staff member who worked as an independent expert adviser to help the agency coordinate its 2020 spraying campaign in Kenya and Ethiopia, said he saw hundreds of FAO-recruited National Youth Service members handling toxic chemicals in northern Kenya without sufficient training or protective equipment.

“I was shocked,” he told Grist. “I was furious about it. Can you imagine this happening in Europe?”

In April 2020, at the height of the locust upsurge, the Taleh farmers attended an emergency training hosted by staff of the Ministry of Agriculture’s Garissa County office. During an informal three-day demonstration, Adan said they were briefed on pesticide-spraying techniques. (Ahmed Sirat, a retired agricultural extension officer who worked with the Taleh farmers at the time, confirmed the training took place.)

After receiving their allotted chemicals, the farmers set off to salvage their crops. Adan said they were warned during the training that the pesticides are dangerous to humans, but they were not provided with specific chemical profiles or protective equipment.

The farmers burned through the first round of pesticides within a matter of days. This fenitrothion-heavy batch came in 500-milliliter bottles, which Sirat had shown them how to mix with water. Fenitrothion is an inexpensive, hazardous pesticide widely used in countries like Brazil, Japan, and Australia. However, it has not been approved for use in the U.S. because it can cause nausea, dizziness, and confusion at low exposures — and respiratory paralysis and even death at high exposures. The pesticide was so strong that some of the locusts died upon contact, falling right off the fruit trees. Clearly, the chemicals were working. But the farmers needed more.

On behalf of his farming committee, Adan requested more pesticides from the county agricultural extension officers. This time, they came in 20-liter cans. “There was a picture of an airplane on the can,” Adan recalled. In retrospect, he believes they were given chemicals meant for aerial spraying, rather than ground operations.

The farmers agreed to spray as a team, moving in sync. Adan remembers crouching as he mixed the chemicals with water, as instructed. He then poured the pesticide into a knapsack sprayer, a device consisting of a pressurized container that disperses liquid through a hand-held nozzle. As he was preparing to hoist the sprayer on his back, Adan accidentally hit the nozzle, spilling its contents across his stomach and back and down his groin and legs. He didn’t think much of it; the immediacy of the locust hordes captured his full attention. Adan repeated the operation and only washed the chemical off his body with water after attending to his crops.

The farmers’ efforts eventually paid off. They were able to protect some of their crops and sold them after harvest. But the farmers have since been suffering from a range of health effects that they attribute to pesticide exposure. For months after spilling chemicals on himself, Adan felt sick. A year later, in April 2021, the malaise culminated in an inability to pass urine. His muscles grew weak, and he often found himself easily fatigued.

Hussein Abdi and Adan Hussein Yusuf, who also work on Taleh Farm, were exposed to milky clouds of the pesticide when they were spraying their mango trees in 2020. The chemicals irritated their eyes, and both farmers have since had eye surgeries at hospitals in Garissa. Abdi still struggles with light sensitivity and wears shades nearly all the time, even on overcast days.

In response to Grist’s questions about the Taleh farmers’ health issues, Garissa County officials denied issuing pesticides to farmers. Ben Gachiri, an officer with the Garissa County communications office, said that it was “impossible that the farmers could have been instructed to do this themselves.” In a written statement, he claimed that no farmer or volunteer was ever issued locust-control pesticides or lodged complaints about pesticide exposure.

The FAO’s assessment, however, tells a different story.

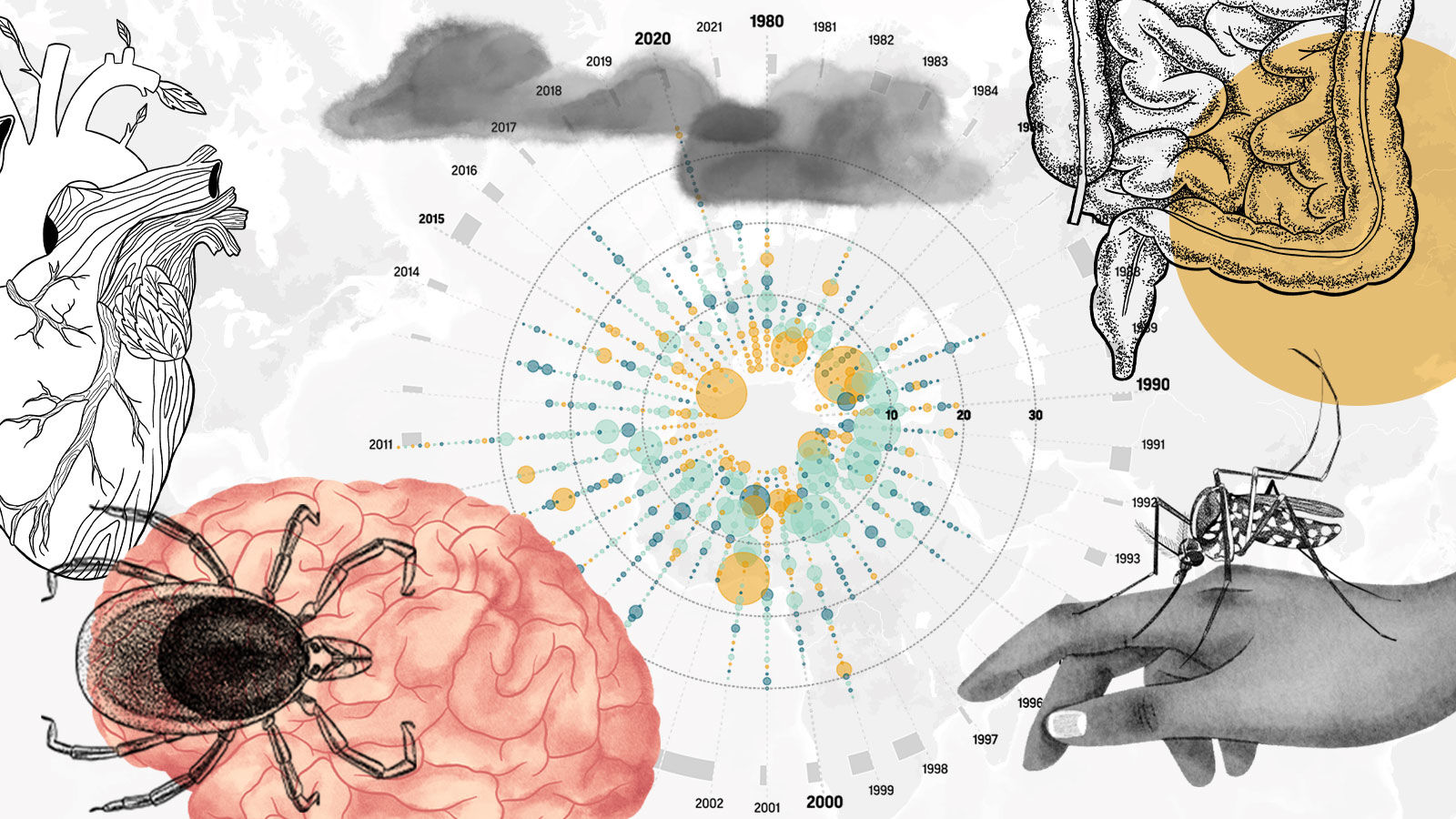

Massive locust surges have threatened farmers throughout the ages, but the swarms have been escalating in recent decades. Desert locust outbreaks require the perfect brew of weather, moist soil, and vegetation conditions. Researchers have found that increases in temperature and rainfall in desert regions, as well as high wind speeds during tropical cyclones, create an ideal environment for locusts to breed and migrate. The fact that many of these conditions have been amplified by climate change has only made locust outbreaks more likely.

The FAO has supported synthetic pesticides as the primary method of locust control since their popularization in the 1980s. A 2021 analysis of FAO pesticide purchase data by the environmental news website Mongabay found that more than 95 percent of the pesticides the agency delivered to East African nations during the locust outbreaks were proven to cause harm to humans and animals. Chlorpyrifos, which the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency had already determined to have no safe level of exposure, made up more than half of the haul. (Scientific evidence linking chlorpyrifos to a slew of neurodevelopmental harms ultimately led the U.S. agency to ban its domestic use in 2021.)

The FAO is well aware of the harmful health effects of chlorpyrifos and other organophosphate pesticides, which it categorizes as “extremely hazardous.” According to an internal 2020 FAO report, which Grist obtained through an officer at Kenya’s Ministry of Agriculture, FAO staff and consultants observed spray sites across 18 counties in Kenya from July to September of that year. (The FAO has not replied to queries about why the document is not publicly available.)

The report found the agency failed to conduct a full environmental and social impact assessment as required under Kenya’s environmental laws, given the state of emergency produced by the massive locust outbreak. Most of the decisions made with regard to locust mitigation efforts remained opaque to the communities most affected, who received little to no guidance on the pesticides’ toxicity and were not briefed on their health or environmental effects. At several operation sites in Kenya’s far north, “communities complained of lack of information and communication” during locust control operations within their vicinity, the report noted.

In Samburu County, northwest of Garissa in Kenya’s Great Rift Valley, FAO monitoring found that “non-trained personnel” took the lead on ground-spraying operations, leading to rampant user errors. The Locust Pesticide Referee Group, an independent body of experts that advises the FAO on pesticide use, recommends that knapsack-sprayers distribute 1 liter per hectare of land, which is roughly 0.11 gallons per acre. But the report noted that the untrained volunteers had sprayed about 3.63 gallons per acre — more than 30 times the recommended amount — on a rainy day when pesticides are likely to run off and pollute soil and water sources.

In Lodwar, northwestern Kenya’s largest town, the FAO had trained a crew of 106 National Youth Service members on pesticide management and safety. Still, some crew members “complained of itchiness on skin during spraying,” the report noted. FAO monitoring staff noted that young children were seen playing next to carelessly disposed gloves, masks, gumboots, overalls, safety goggles, and uncollected pesticide drums.

The scathing report found that farmers and community members weren’t properly informed about when spraying occurred, how long it would last, or what the chemicals’ effects were on human and animal health. As a result, around Oldonyiro, a heavily sprayed area in Isiolo County a few hundred miles northwest of Garissa, local Ministry of Agriculture authorities did not collect accounts of cow, camel, and goat mortalities that came from community members.

Less harmful alternatives to synthetic pesticides exist and have proven their efficacy, but they are not yet in widespread global use. Biopesticides developed from Metarhizium acridum fungal spores were first tested in 1989 under a private research program, after a particularly vicious three-year locust plague in East Africa. After years of painstaking testing, a commercial product finally hit the market in 2005. The FAO first used a version of the biopesticide on an operational scale in Tanzania in 2009, and later in Madagascar and Central Asia.

In 2020, Metarhizium-derived biopesticides were used on a large scale with great success in Somalia. The effectiveness was comparable to that of synthetic pesticides: 60 percent mortality after 10 days, increasing to 83 percent after 14 days. Though biopesticides have a higher initial cost than synthetics, researchers found that this was quickly offset by low environmental damage and the elimination of disposal costs. As a bonus, biopesticides can boost honey production, a common livelihood in East Africa, since they are far gentler on pollinators than synthetic chemicals.

Despite their proven track record, companies have largely been unwilling to invest in such biopesticides. That’s because the products are highly targeted and cannot be used on as wide a range of pests. And because they are derived from nature, producing identical batches has proven tricky.

“Economically it’s not as viable, and therefore not of interest to governments –– or companies,” said Pantenius.

FAO representatives declined to speak directly with Grist about the agency’s pesticide procurement procedure, or to elaborate on how decisions were made concerning its locust campaign in Kenya. To this day, the FAO has declined to publicly release reports about documented user error and exactly how much of each pesticide was sprayed.

But in an emailed statement from the FAO’s East Africa regional office, the agency emphasized that it was up to individual countries to select which pesticides they would authorize for use, and that locust control measures were “closely monitored to minimize risks to people and communities.” The FAO denied that farmers or any other untrained community members participated in spraying. The statement added that the FAO encouraged countries to use biopesticides, but that limited production of these alternatives made them insufficient for the scale of the outbreak.

Pantenius said that the FAO has worked to protect crops from being devoured by locusts in cost-effective ways while also considering environmental damage. However, he believes that it and other international humanitarian organizations must put more pressure on governments to make better-informed decisions. “It’s time that we get to a point where we draw a line and say, ‘We’re willing to help you, but won’t provide chemical pesticides,’” he said.

“By the time locusts cross over the crops, it’s already too late [to consider alternatives],” Pantenius added. “Once the plague is over, everyone quickly moves on to more pressing issues.”

Three years after the locusts first arrived, Adan has realized that he could be dealing with effects from pesticide exposure for the rest of his life.

“I’m a lot better now, but it still hurts to stand up,” he explained, lightly pounding the muscles around his thighs. Until recently, he had also been struggling with incontinence.

To date, Adan has undergone five surgeries, inserting and removing catheters, in an attempt to address a series of urinary tract complications from the accident. He estimates that the hospital bills have racked up to nearly $10,000 — he was forced to sell 14 camels at approximately $400 each to help cover the costs, and neighbors and relatives pitched in.

Adan’s infertility — a known ramification from exposure to synthetic organophosphates such as chlorpyrifos — has been an even greater blow, given local cultural expectations. “When one stops procreating, one’s life is effectively over,” his son Abu explained.

As of early this year, Adan’s health had deteriorated. He started having trouble passing urine again and may need a sixth surgery. Abu said that they are considering applying for a medical visa to India, with the hopes that overseas expertise might solve his lingering urinary tract issue.

On a sweltering day under the equatorial sun late last November, Adan stood beneath the shade of overgrown mango trees with his friends Abdi and Yusuf. He recalled a local saying about locusts, revealing the enduring nuisance that the pests have been in the region — existing as mere folklore for some generations, a living nightmare for others.

“Anyone, even a cow, who eats too much, you’re said to be eating like an ayah — a locust.”

Adan remains concerned about future outbreaks. If a better preparedness plan is not put in place, “It will cause more damage than this,” he said. “This is something that comes with God’s plan — that can’t be predicted by a human being.”

Anthony Langat contributed reporting to this story.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How a UN-led fight against locusts took a toxic toll on Kenyan farmers on Aug 23, 2023.