Since it started measuring waste diversion from landfills in 2006, when it recycled only 4.6%…

The post Earth911 Podcast: Christy Briggs Scores a Sustainability Touchdown at Seattle’s Lumen Field appeared first on Earth911.

Since it started measuring waste diversion from landfills in 2006, when it recycled only 4.6%…

The post Earth911 Podcast: Christy Briggs Scores a Sustainability Touchdown at Seattle’s Lumen Field appeared first on Earth911.

This story is part of Record High, a Grist series examining extreme heat and its impact on how — and where — we live.

Summer afternoons on Florida Bay are a wonder. The sky, bright blue and dotted with clouds, meets the glassy water in a blur of blue that melts away any sign of the horizon. Wading birds rustle in the verdant branches of mangroves. Beneath the surface, fish and other creatures dart among tangled mangrove roots adorned with colorful sponges and corals. Out in the shallow flats, redfish forage for crabs, snails, and shrimp hidden in fields of seagrass as manatees graze and bottlenose dolphins hunt.

But this vast estuary, which by some estimates stretches at least 800 square miles — roughly the size of Tokyo — and comprises about one-third of Everglades National Park has looked very different lately. In the mangroves, anemones and jellyfish, stressed by unprecedented water temperatures, appear ghostly white. Suffocated fish and soupy patches of dead seagrass litter the sandy flats. Sponges and coral languish beneath thick sheaths of algae.

This summer, as water temperatures across the Everglades reached triple digits, much of the nation’s attention focused on the Atlantic side of the Keys, where rapid bleaching devastated much of the Sunshine State’s beautiful coral reefs. But in Florida Bay, which sits on the west side of the Keys, many marine species have been fighting their own battle with bleaching and other effects of extreme heat, sending a strong, if silent, message about their own stress and the health of the essential habitat they inhabit.

Normally resilient creatures are struggling to survive. The record heat has not only threatened individual species — an astonishing effect on clear display in the warm South Florida waters — but the expansive and interconnected habitats, stretching from the Florida Bay to the wider Everglades and beyond.

“It’s not a grass problem, it’s not a coral problem, it’s not a sponge problem,” said Matt Bellinger, owner and operator of Bamboo Charters in the Keys. “It’s a complete ecosystem problem.”

Jerry Lorenz, the state director of research for Audubon Florida who has decades of experience in Florida Bay, likens the risks facing the estuary to playing Jenga.

“You can pull this piece, you can pull out that piece,” he said. “And you can pull out a lot more pieces. But eventually, you’re going to pull out one last piece that’s going to topple the whole thing. And that’s exactly the kind of thing we’re seeing here.”

Nestled between the southernmost end of Florida and the Keys that stretch 180 miles westward toward the Dry Tortugas, this shallow estuary features swaths of luscious seagrass. These marine prairies cover the vast majority of the bay floor and shelter lobster, shrimp, crab, and other creatures. Thousands of mangrove islands protect juvenile reef fish, invertebrates, and nesting birds like the endangered roseate spoonbill. All of them play a crucial supporting role in a much larger ecosystem. The Florida Bay is intrinsically linked to the Atlantic side of the Keys, and many fish and other species make their home in both.

“A lot of these reef species go back into the Bay, treating it as a nursery,” said Kelly Cox, director of Everglades policy at Audubon Florida. “There’s a lot of interaction between the ecosystems. So a healthy Florida Bay means healthy fish populations on the reef and vice versa. And that goes for crustaceans, it goes for sponges, it goes for all different types of fish and wildlife.”

A vibrant and productive Florida Bay does more than allow wildlife to thrive — it boosts commerce, too. Beyond offering ample opportunities for sport and recreational activities, the estuary supplies a bounty of seafood.

“Everything in our economy is somehow intertwined with our environment,” Cox said. “We’re talking about expansive reliance on healthy marine ecosystems in the state of Florida.”

The health of the bay and surrounding areas declined significantly in early July during the four consecutive days that Earth experienced the hottest average global temperatures ever recorded. Weeks of intense heat, exacerbated by the lack of usual summer rain showers, saw shallower areas of the Florida Bay top 100 degrees Fahrenheit. During the scorching weather, neighboring Manatee Bay recorded a startling water temperature of 101.1 degrees, which might be a world record. While snorkeling recently on the western edge of Florida Bay, Lorenz recalled it being too hot to swim.

“It was uncomfortable,” Lorenz said. “When I swam up under the mangroves, it was jam-packed with fish. I just had this impression go through my head that these guys are trying to stay in the shade.”

The astonishing effects of the heat wave on the bay may be partly responsible for the extensive coral bleaching and mortality seen across the reef of the Atlantic side. This year’s intense heat evaporated a lot of the bayside’s water, leaving it extremely salty and, therefore, dense. In normal conditions, when natural currents pull the bay water into the Atlantic, the warmer water sits on the ocean surface.

But this time, something unusual happened. The extremely hot and salty bay water sank — a phenomenon known as a reverse thermocline — below the cooler Atlantic Ocean water, and smothered coral reefs down to 30 feet below with its extreme temperatures, resulting in mass coral bleaching and, in some cases, instant death.

Hotter, saltier water poses a grave threat to marine species that can only withstand so much stress before their metabolic processes begin to fail. Such strain can lead to bleaching, seagrass die-offs, algal blooms, and fish kills. If the salinity of Florida Bay rises to that of the Atlantic more than 10 or 15 days a year, “it knocks the whole system out of balance,” Lorenz said.

Dramatic increases in water temperature can throw a potentially catastrophic knock to the entire ecosystem where even the most robust and resilient species, including glass anemones, relatives to coral, are fighting to survive. These common and resilient spindly invertebrates, normally difficult to see due to their brown hues, are now easily spotted in ghostly white clusters — a sign that something is very wrong.

Bleaching occurs when corals, anemones, and jellyfish, pushed beyond their thermal limits, eject the algal cells in their tissues. Left without their colorful symbiotic counterparts, the animals are vulnerable to predation, starvation, and disease, said Anthony Bellantuono, a biological sciences postdoctoral researcher.

In his laboratory at Florida International University, marine biologists have tested these creatures at temperatures between 89.6 and 93.2 degrees F. Yet in the most recent heat wave, the waters of the bayside and southern Everglades reached heights never tested in the lab. Bellantuono has been stunned to see the widespread bleaching, which likely extended across the length of Florida Bay and beyond, among such a robust species.

“Anemones are these super-resilient creatures that are highly tolerant to stress,” Bellantuono said. “It should be a bit of a concern that they’re bleached so thoroughly. They don’t bleach often and it is really, really bad when they do.”

And it’s more than animals at risk; the seagrass they nestle in and the mangroves that harbor them are threatened as well. That could reduce the amount of oxygen in the water, creating another threat for the wildlife of the bay.

Compounding the problem, Florida Bay battles an insufficient influx of fresh water. Natural outflow across the Everglades has been significantly disrupted, with much of its historic flow now diverted by canals, roads, agriculture, and development — and considerably less ending up in the estuary. Insufficient fresh water to balance the influx of nitrogen, phosphorus, and other pollutants from the Gulf of Mexico, coupled with extremely hot temperatures, could leave the water uninhabitable.

Conservation organizations such as the Audubon Society have been working to educate and empower audiences to engage, through citizen science and efforts to push policymakers to act, with an environmental challenge that otherwise might seem insurmountable.

“It’s really, really hard to sit on the sidelines,” Cox said. “We’re not going to be able to pull seagrasses out of the water, right? We’re not able to pick up wading birds and move them to other locations. These are things that Mother Nature is going to have to handle on her own, and we have to hope that the interventions that we’ve designed so far are enough to sustain a lifeline.”

Cox said that the northeastern portion of Florida Bay that her team covers has yet to see any seagrass die-offs this season, primarily due to long-term efforts — such as the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan, the single largest restoration underway in the South Florida ecosystem — to facilitate the flow of fresh water, much of which comes from rain, through the Everglades and into the bay.

“The mechanisms and interventions that we put in place are providing that little glimmer of hope that we might make it through this heat wave, and that the seagrass beds are going to be able to hold on in the national park,” she said. “That’s really encouraging for us.”

Yet both Lorenz and Bellinger confirmed they had seen fish and seagrass die-offs in other parts of Florida Bay. And the heat is far from over: Above-average temperatures are expected over the next several months. For those in South Florida, the effects of persistent extreme heat and high water temperatures in the Florida Bay and the surrounding marine ecosystems are a sign of a potentially dire future.

“These are warnings,” says Bellantuono. “When the most tolerant creatures in our shallow waters are all bleaching, starkly white … it’s an alarm bell for these ecosystems. Will these ecosystems be as strong as they have been? It seems uncertain. When we see the ecosystem melting around us, I hope it makes people as scared as they should be about this.”

The videos in this story were created by Gabriela Tejeda.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline It’s not just coral. Extreme heat is weakening entire marine ecosystems in Florida. on Sep 18, 2023.

Indigenous peoples are largely being excluded from trillions in global spending to mitigate climate change, with governments doing little to ensure that climate funding not only respects Indigenous rights but supports Indigenous-led green projects.

That’s according to a new report focused on green financing by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous Peoples, José Francisco Calí Tzay, which will be discussed at the U.N.’s Human Rights Council this month. The 54th regular session of the United Nations body kicked off last week in Geneva.

“The shift to green finance is necessary and urgent, and if done using a human rights-based approach it can be a source of opportunity for Indigenous Peoples to obtain funding to preserve their lands, knowledge and distinct ways of life, and to create economic opportunities that may help them to maintain and strengthen their indigenous identity,” wrote Calí Tzay, who is Kaqchikel, among the Mayan peoples of Guatemala.

The Special Rapporteur’s report comes eight years after the Paris Agreement, an international climate change treaty to limit global warming, called for $100 billion in annual funding to address the effects of climate change in developing countries. That goal is still aspirational, but overall sustainability investment continues to grow, with a 2020 analysis estimating it reached $35.3 trillion in 2020.

Green financing, a term that broadly refers to investments in climate action and sustainable development, is increasingly seen as a critical tool for addressing climate change. However, a 2019 working paper from the Asian Development Bank Institute concluded that financial institutions continue to support fossil fuel projects over green development because the former have higher rates of return. The study’s authors emphasized a need to boost green financing in order to reach sustainable development goals established by the United Nations the same year as the Paris Agreement.

Many green development projects take place on Indigenous lands. At Thacker Pass in the United States, Indigenous nations have sued the federal government over a lithium-mining operation that’s expected to support the Biden administration’s push toward electric vehicle batteries, but at the cost of producing hazardous waste and disturbing burial sites. In Norway, wind turbine development continues to violate the rights of Sámi communities. The Special Rapporteur’s report says more green projects are expected to take place on Indigenous lands and governments should ensure their rights are respected.

Calí Tzay points out that Indigenous peoples have largely been excluded from having a say in such green energy projects, with many communities being perceived simply as “vulnerable” rather than as rights holders. As well, an analysis by the Rights and Resources Initiative and the Rainforest Foundation Norway found that just 17 percent of $270 million in global climate and conservation funding that’s invested annually in Indigenous and local communities actually supports projects led by Indigenous people. Far less — only 5 percent — goes to projects led by Indigenous women.

Some international finance organizations have policies requiring free and informed consent designed to safeguard such rights, but Calí Tzay added that they aren’t consistently applied.

“In Africa and Europe, wind farms and geothermal projects have been undertaken without their free, prior and informed consent,” he wrote. “Too often, Governments and foreign investors assume that land used by nomadic herders and pastoralists is simply “empty”. Investors too often rely on formal registration of State or private ownership, or government assurances that land is available to use, when a diligent independent analysis prior to investment would have indicated that the land may be subject to the customary rights of Indigenous Peoples.”

The Special Rapporteur emphasized the importance of making it easier for Indigenous peoples themselves to access funding, echoing concerns raised by the Indigenous Peoples of Africa Co-Coordinating Committee, or IPACC, an organization that represents more than 100 Indigenous communities in Africa. The group was among several that submitted comments to Calí Tzay ahead of the report’s publication in July.

“Issues of lack of effective consultations are common in most green financing projects,” IPACC wrote, noting that in some cases Indigenous peoples live in vast landscapes with limited communication. Such consultation is extremely important when projects such as hydroelectric dams have the potential to displace Indigenous communities or use their land and resources “without their consent or compensation.”

The Special Rapporteur concluded state governments bear the largest responsibility for ensuring Indigenous people are active participants in green projects by establishing regulations and legal frameworks to ensure their involvement, but noted private funding, like philanthropy, may have more flexibility to directly support Indigenous groups.

Not everyone who provided input on the report agreed with that conclusion. The Indigenous Environmental Network, a U.S.-based coalition of Indigenous activists, was skeptical about the push for private financing, writing that capitalistic pressures are likely to prevent private funders from respecting Native rights.

“Placing climate finance in the hands of the private sector prioritizes the chase for perpetual growth over Mother Earth and threatens the lands, livelihoods, and cultures of Indigenous Peoples and impacted communities,” the coalition wrote. “In reality it is the endless search for profit that has driven us to the current state of climate catastrophe.”

Still, Calí Tzay stopped short of discouraging private funding for green projects, contending that better public and private policies that guarantee the rights of Indigenous peoples could make a difference.

“The purpose of the present report is not to condemn or deter the financing of green projects and green market strategies,” he wrote, “but to ensure that Governments and other financial actors take all precautions to ensure their support for the much-needed transition to a green economy and that climate change action does not perpetuate the violations and abuses currently plaguing extractive and other fossil fuel-related projects.”

An interactive dialogue about the report is expected to take place on Thursday, September 28.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Indigenous peoples are being excluded from a global pool of climate cash on Sep 18, 2023.

For decades, communities living in the shadows of the nation’s petroleum refineries were in the dark about the quality of the air that they breathed. Residents in places like Port Arthur, Texas, and Artesia, New Mexico, could sense their exposure to toxic pollution on days when the air was thick with the sweet smell of benzene, a carcinogen. But access to information on the actual levels of chemicals in the air — data that could help vulnerable individuals make critical decisions regarding their health — was largely unavailable.

That changed in 2018, when the federal Environmental Protection Agency, EPA, began requiring refinery operators to monitor concentrations of benzene around the fencelines of their facilities — and, crucially, to publish the results of those measurements online. Since then, benzene concentrations near the country’s 118 refineries have trended downward. However, a lack of enforcement and a dearth of monitoring data has still left some communities behind, according to a new report from the Office of the Inspector General, or OIG, the EPA’s internal watchdog.

The report authors analyzed data from 18 refineries that exceeded the federal benzene “action level” — the level above which operators are required to take corrective measures — between January 2018 and September 2021. They found that 13 of them continued to violate federal standards in 20 or more weeks after their initial violation. Many of these refineries, the report noted, are located in and around neighborhoods of color. The report raises doubts that merely asking companies to collect and report their own data as well as analyze the causes of their own violations, as the 2018 fenceline monitoring requirement did, will lead them to keep their toxic emissions below permissible levels.

Environmental advocates argue that such measures must be accompanied by robust enforcement action from the EPA.

“Even if it has helped a little bit, it’s not enough,” said Ana Parras, co-director of the Houston-based Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Group, of the agency’s fenceline monitoring requirements. “The lack of enforcement, it’s always been there.”

The report comes as the EPA has made efforts to incorporate similar fenceline monitoring requirements into other air pollution regulations. Most recently, the agency proposed to require monitoring in a rule that covers many of the nation’s most toxic chemical plants, a high percentage of which are concentrated in the industrial corridors of Texas and Louisiana. Like the regulations for petroleum refineries, these rules would require operators to analyze the cause of their violations and submit a “corrective action plan” to the agency if they continue to violate federal standards.

When the EPA issued updated regulations for petroleum refineries in 2015, it was the first time that operators of large industrial facilities were required to monitor and report their toxic emissions. The new rules were seen as a novel approach to pollution reduction: Until that point, refinery pollution was controlled through various technologies designed to capture and eliminate emissions; with the exception of occasional facility inspections, regulators effectively took operators at their word that they were operating correctly. When the new regulations went into effect in 2018, refinery personnel had to submit measurements to the EPA every two weeks, and conduct an analysis to identify underlying problems if their average benzene levels exceeded the federal action level of 9 micrograms per cubic meter of air over that period.

The advent of these requirements surfaced information that was previously unavailable to the public and regulators alike. As the data slowly came online, it became clear that the emissions around certain refineries were severe, in some cases exceeding federal standards for many months on end.

Despite this, state and federal regulators failed to curb a number of these emissions. The OIG report pointed to several potential reasons for this, including operators’ failures to identify the cause of their emissions and limited enforcement action by the EPA. In some cases, enforcement was stymied by the fact that refinery operators did not submit monitoring results at all. In others, they estimated nearby industrial plants’ contributions to airbore benzene levels using computer models, instead of actual air monitors, as required by the law.

A failure to reduce benzene levels could cause serious long-term health effects in communities near refineries, according to the report. Benzene is just one of a litany of chemicals released during the process of refining crude oil. Prolonged exposure over years has been linked to leukemia and other cancers of the blood, and breathing high concentrations of benzene in the short term can cause shortness of breath, headaches, and dizziness.

Parras told Grist that residents of cities like Port Arthur and nearby Baytown, Texas, are no strangers to these symptoms. According to the OIG report, Texas is home to 9 out of the 25 refineries where benzene levels exceeded the action level at least once.

“There’s days that you go down there and the smell is so powerful, people don’t want to get off the bus,” Parras said. “This is life on the fence line.”

In its report, the OIG recommended that the EPA improve its approach to addressing unsafe levels of benzene near refineries by providing better guidance to state and local regulators on what constitutes a violation and how to identify gaps in the data that companies submit. The report also advised the agency to develop a strategy to address refineries that continually exceed federal standards. The OIG wrote that the EPA had agreed with its set of recommendations, and that it considered them to be “resolved with corrective actions pending.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline New EPA watchdog report says refineries can’t police themselves on Sep 18, 2023.

Business travel is responsible for a large part of a company’s carbon emissions, negatively impacting…

The post Sustainable Business Travel: Navigating The Road To Greener Journeys appeared first on Earth911.

This story was originally published by Honolulu Civil Beat and is republished with permission.

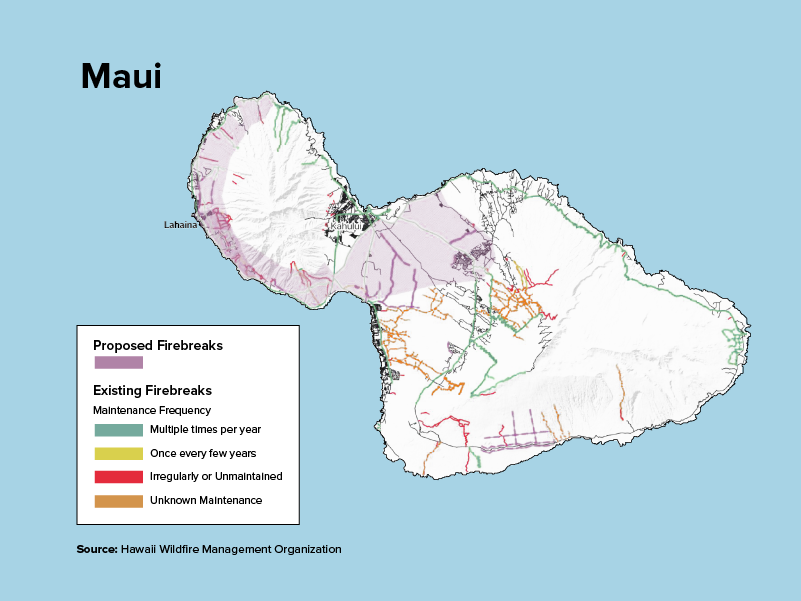

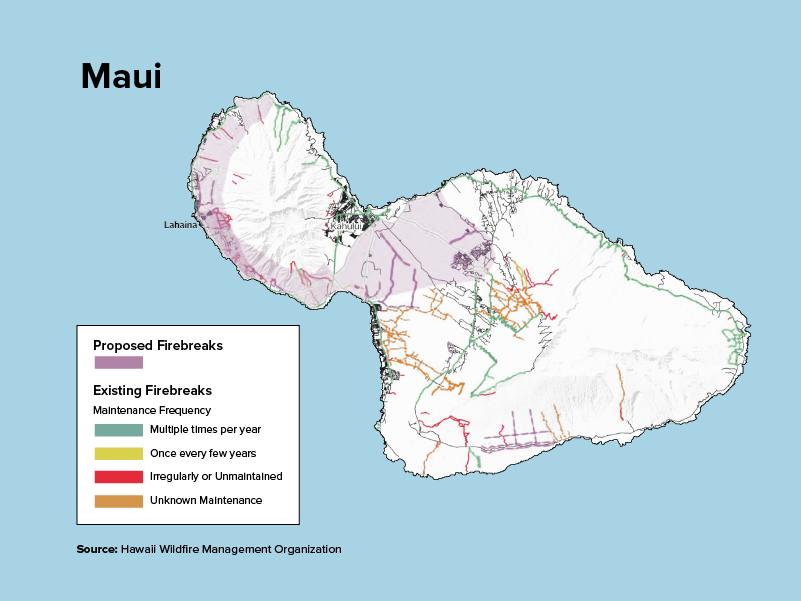

Hawaii maintains a network of firebreaks to keep wildfire from spreading, but that system includes hundreds of miles of gaps that need to be filled to protect communities around the state.

Public and private land managers dealing with the danger face bureaucratic barriers and a lack of money and collaboration.

Managing land to reduce fire danger took on increased urgency after the Aug. 8 wildfires on Maui, including the conflagration that leveled Lahaina and killed at least 115 people.

Both firebreaks and fuelbreaks are used to slow or halt the spread of wildfire. Firebreaks are generally wide belts of bare soil, but roads and rivers can serve the same purpose. Fuelbreaks are actively managed strips of land with minimal vegetation, intended to weaken the intensity and spread of fire.

Hawaii has roughly 4,300 miles of breaks, but needs approximately 350 miles more — accounting for some 400,000 acres, according to 2019 data collected by the Hawaii Wildfire Management Organization.

It’s doubtful that firebreaks around Lahaina on Aug. 8 would have stemmed the spread of the West Maui fire, given the high winds, HWMO co-executive director Elizabeth Pickett said. But the tracts play an integral role in helping firefighters access hard-to-reach areas to dissipate fires’ intensity.

As far back as 2018, fire officials and land managers identified a need for an additional 350 miles of breaks during meetings with representatives of 128 private and public groups and HWMO.

But because those breaks cross federal, state, county, and private lands, there must be collective buy-in and coordination to make it work, as well as money to pay for it all, Pickett said.

“Fire doesn’t recognize fence lines and ownerships and jurisdiction. So we need our fuels management to make sense at the land level,” Pickett said.

The 2018 meetings resulted in an assessment of the state’s needs that has informed much of its work on vegetation management until now.

But the effort has not received enough attention or money, officials say.

Building a firebreak on public land is expensive. The Department of Land and Natural Resources says it can’t afford to do it short of an emergency.

DLNR, which manages 26 percent of the state’s land, maintains just over 320 miles of breaks statewide but only cuts them during active wildfires. The department says the regulatory costs of protecting environmental, cultural, and historic resources make it unfeasible except during emergencies.

Those regulations are waived during active fires, when trained “dozer scouts” from DLNR’s Division of Forestry and Wildlife guide bulldozers to cut ribbons in the landscape to stop fire without destroying important resources.

The result is an “ad hoc network” of firebreaks and fuelbreaks, according to DOFAW forester Michael Walker.

To link it all together across boundaries will take time, staff and funding beyond DOFAW’s current capabilities, Walker says.

A bill that was killed this year would have set aside $3 million over two years for DOFAW to connect Hawaii’s breaks. Even that would have fallen far short, Walker says.

“And it’s not just us — forestry and wildlife — that need fuel reduction funds. It’s ranchers, farmers,” Walker said in a July interview before the Lahaina fire.

Farmers and ranchers are key players in preventing wildfire because they actively manage the landscape, either through grazing or crops. Land no longer used for these purposes has contributed to the spread of wildfire in recent decades.

Unused land has fostered the spread of invasive grasses, many thriving under drought conditions.

Much of this land now borders development.

“The bulk of the housing in Hawaii these days is built on top of old plantation land,” Walker said. “So they’ll develop a piece of it, but then the rest of it is still surrounded by fallow ag land.”

A week ago, a three-acre wildfire threatened three homes in Oahu’s Makakilo, a community that has consistently raised concerns over its single evacuation route. It came up again recently, in the aftermath of the Aug. 8 Maui fires.

On top of evacuation concerns, the Honolulu Fire Department said in a press release that there are too few firebreaks in the unmanaged land bordering the community.

Because wildfire does not respect property lines, it has been a focus for HWMO, which has been working on bolstering communication, funding, and coordination across the state.

That was the goal of HWMO’s 2018 meetings: to test and establish an “all hands, all lands” approach in Hawaii, according to co-executive director Pickett.

HWMO has tested community-based, cross-boundary fire mitigation projects on five of Hawaii’s major islands, allocating $22,000 to each project. They ranged from grazing sheep in Waianae to building a break in Kawaihae on Big Island.

But Pickett recognizes that her relatively small organization has only been able to focus on the community level.

“We want to think about what makes sense across boundaries,” Pickett said.

Not every landowner has been willing to take part. HWMO has focused on working with the willing.

But more needs to be done, including improved fire codes, legislation, and enforcement.

“Where’s the gap? Accountability,” Pickett said.

In light of the Aug. 8 fires, county and state lawmakers appear resolved to stem the risk of wildfire in Hawaii.

Last month, Honolulu Mayor Rick Blangiardi ordered a review of Oahu’s fire risk, including firefighting assets and capacity, unaddressed needs and system vulnerabilities.

Last week, the Hawaii House of Representatives established working groups to focus on several wildfire topics to inform bills in the next legislative session.

One of those groups will be focused on wildfire prevention.

One of its 16 members, Rep. David Tarnas, believes the state should coordinate the establishment of a robust network of breaks and creating incentives for vegetation management, because it all costs money.

The government entity mandated to do the work — DOFAW — has been underfunded for years, Tarnas said.

“We can’t just leave it to a nonprofit,” Tarnas said. “You know, we have to step up as a state and fully fund our natural resources and fire protection program.”

Civil Beat’s coverage of Maui County is supported in part by a grant from the Nuestro Futuro Foundation.

Civil Beat’s coverage of climate change is supported by the Environmental Funders Group of the Hawaii Community Foundation, Marisla Fund of the Hawaii Community Foundation and the Frost Family Foundation.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Hawaii needs to build hundreds more miles of firebreaks to protect against wildfire on Sep 17, 2023.

This story was originally published by The 19th and is republished with permission.

Pregnant people exposed to extreme heat are at higher risk of developing life-threatening complications during labor and delivery, according to new research published in the Journal of the American Medical Association last week. The research adds to a growing body of evidence showing the impact extreme heat has on a pregnancy, while also making a distinction between long-term exposure and events like heat waves.

“I think this [distinction] is really important,” said Ashley Ward, director of the Heat Policy Innovation Hub at Duke University who was not involved in the study. “Most of the research around pregnant women has centered on acute events like a heat wave … but honestly, what we are all experiencing this summer is an excellent example of really what I would consider chronic heat exposure.”

The researchers used data provided by Kaiser Permanente Southern California, a health care network, to identify over 400,000 pregnancies in the region that took place between 2007 and 2018. They then looked at temperature data from that same time period and used the daily maximum temperature to figure out how many days of heat — characterized as moderate, high or extreme — pregnant people were exposed to throughout their pregnancy, breaking it down by trimester.

The study found significant associations between both short- and long-term exposure (usually defined as 30 days or more) of environmental heat during a pregnancy and severe maternal morbidity. Severe maternal morbidity is a term used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to define 21 unexpected outcomes during labor or delivery that are considered near misses for maternal mortality. This could include cardiac arrest, eclampsia, heart failure, sepsis, and ventilation. (The primary findings excluded whether a blood transfusion occurred during delivery, usually an indicator of severe maternal morbidity, because the data wasn’t detailed enough.)

Researchers found that a high exposure to extreme heat through the duration of the pregnancy or in the third trimester was associated with a 27 percent increase in these risks. Exposure to a heat wave during the last gestational week was also associated with an increased risk of life-threatening delivery complications.

Globally, this summer was the hottest on record. Phoenix broke a record when the temperature topped 110 degrees 31 days in a row. Dozens of other cities including in Texas, Louisiana, and California have experienced their own record-breaking temperature streaks.

While the study did not find significant demographic differences when breaking down the data by race and ethnicity, it did find that people with lower education levels had higher heat-related risk of severe maternal morbidity, said Anqi Jiao, an author of the study. This finding points to possible mitigation strategies that doctors, nurses, and others in public health could take.

“They may pay more attention to these mothers with lower education levels as a targeted intervention,” she said. “Those mothers with lower educational attainment may have very limited knowledge to understand extreme heat as an environmental hazard, and they may not understand why the extreme heat could affect their pregnancy outcome.”

Importantly, the study also found associations between heat exposure and cardiovascular events during labor and pregnancy. Cardiovascular conditions are now a leading cause of pregnancy-related deaths in the United States, a crisis that has only gotten worse in recent years despite medical advances.

Ward applauded the decision to focus on severe maternal morbidity in the study. Other studies have looked at the impact of heat on birth outcomes or maternal health issues like gestational diabetes.

“This is really important because severe maternal morbidity is basically very nearly maternal mortality,” Ward said. “It is the most extreme of health outcomes for pregnant women. And so it’s very serious.”

She points out that it would also be useful if a study like this looked at overnight temperatures, which could further pinpoint what other underlying factors may contribute to heat exposure, she said. “Overnight temperatures indicate maybe a lack of access to cooling at night, where your body doesn’t have the time to recover,” she said, as an example.

Further research could also highlight what kind of exposure people face during the day, related to different socio-economic factors like the type of job a pregnant person has, Ward said.

“A lot of times when we think about occupational exposures we tend to think about men, but that’s just not true. Women work in high-exposure jobs too. They work in the food industry in kitchens that have high heat, a lot of them may be caregivers in an environment in which there is not adequate cooling. A lot of women work in manufacturing, where indoor heat exposure is a thing,” she said. “So it’s about thinking through the underlying factors that are contributing to this.”

Jiao said she and others from her research team plan to look at other temperature metrics in future studies, as well as different climate factors like wildfire smoke.

Ward finds this study to be a significant contribution to our understanding of heat and says it has important implications for emergency planners who can use this research to better understand the dangers of exposure to chronic heat.

“These kinds of studies help inform those kinds of planning and preparedness activities so that they are targeted and that they have the most impact,” she said. “Anytime we get research that helps us understand … the nuances of heat exposure, it helps us protect people better, and that information gets incorporated into the planning and preparedness infrastructure — at least that’s the hope, right?”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Extreme heat is linked to higher risk of life-threatening delivery complications for pregnant people on Sep 16, 2023.

Originally introduced to North America in the 1800s, the European starling is a magnificent bird, tawny brown with white spots in winter, shining with iridescent purple and green feathers in summer.

Not only are they dazzling, since starlings are also some of the most skilled vocal learners, with the ability to mimic the calls of as many as 20 other species, according to Cornell University’s All About Birds.

Starlings learn an impressive variety of calls, warbles, whistles and songs during their lifetimes, a press release from The Rockefeller University said. Besides being superior vocal learners, a new study has revealed that these remarkable birds are also exceptional at problem solving.

“There is a long-standing hypothesis that only the most intelligent animals are capable of complex vocal learning,” said Jean-Nicolas Audet, co-author of the study and a research associate in the laboratory of Erich Jarvis at The Rockefeller University, in the press release. “If that is true, then complex vocal learners should also be better at cognitive tasks, but no one had ever demonstrated that before.”

Complex vocal learning is defined as having the skill to learn and remember a large variety of sounds. Only a small number of animal groups are able to do this, including whales, seals, elephants, bats, humans, parrots, songbirds and hummingbirds.

The research team focused on songbirds, ranking the complexity of their vocal learning using three metrics: whether or not the bird was able to learn new calls and songs through their lifetime, how many calls and songs were in their repertoire and if they were able to mimic other species.

The study, “Songbird species that display more-complex vocal learning are better problem-solvers and have larger brains,” was published in the journal Science.

The researchers spent three years capturing hundreds of wild birds covering 21 species at The Rockefeller University Field Research Center, located on 1,200 acres of protected land that is home to a wide variety of ecosystems in the Hudson Valley.

“It’s a protected area, which means the animals have limited exposure to humans,” said Mélanie Couture, a research assistant who co-authored the study, in the press release. “This is ideal for studying the behaviors of wild birds — what they can do, and how they react to cognitive tasks.”

There were just three types of birds that were able to mimic other species, which Audet said is “the epitome of vocal learning.” They were blue jays, gray catbirds, who are related to mockingbirds, and starlings. The research team ranked these three highest in vocal learning capability.

The team conducted a series of cognitive evaluations on 214 birds of 23 species, including two that had been raised in a lab. The researchers looked at their ability to problem solve by challenging them to pull a stick, pierce foil or remove a lid in order to get to a treat. They also tested for self-control and learning associated with color.

The research team found a strong connection between vocal learning aptitude and problem-solving abilities. Bluejays, starlings and gray catbirds were the best at problem solving, as well as the most adept vocal learners. And birds who were best at navigating around obstacles in order to get to a treat also had more advanced vocal learning ability.

The research team also discovered that birds who were highly skilled problem solvers and vocal learners had larger brains in relation to body size.

“Our next step is to look at the brains of the most complex species and try to understand why they are better at problem solving and vocal learning,” Audet said in the press release. “We have a pretty good idea of where vocal learning happens in the brain, but it’s not yet clear where problem solving occurs.”

The findings of the study suggest that the evolution of problem solving, vocal learning and brain size may have occurred together, possibly in order to boost biological fitness. Jarvis has termed the collection of traits — based on the study’s findings and previous work that assessed how well vocal learners could dance to a beat — the “vocal learning cognitive complex.”

“Our findings help support a previously unproven notion: that the evolution of a complex behavior like spoken language, which depends on vocal learning, is associated with co-evolution of other complex behaviors,” Jarvis said in the press release.

The post Superior Vocal Learning in Birds Linked to Better Problem Solving and Bigger Brain Size appeared first on EcoWatch.

After days of churning in the Caribbean, where Hurricane Lee reached Category 5 status with maximum sustained winds of 165 miles per hour (mph), the storm is headed toward the Atlantic Coast of New England and Canada.

According to the National Hurricane Center, the “large and dangerous” Category 1 storm is projected to make landfall this weekend.

“It’s a batten-down-the-hatches kind of day,” said Kim Gillies, owner of Maine’s Boothbay Harbor Marina, as The Associated Press reported.

Emergency management agencies and the U.S. Coast Guard warned communities in New England to prepare for the storm, as residents removed boats from the water.

Nova Scotia and New Brunswick were under a hurricane watch, while a tropical storm warning was in effect for Bermuda and Massachusetts — including Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket — north to the border of the U.S. and Canada, the National Hurricane Center said.

“Today is the last day to prepare,” meteorologist Stephanie Abrams with The Weather Channel said on CBS Mornings, as reported by CBS News. “Conditions go downhill tonight, and tomorrow, Lee will be battering parts of New England. The strongest winds are expected to be along the coast.”

The National Hurricane Center predicted the southern portion of New England would start seeing tropical storm conditions, including flooding along the coast, this afternoon. Lee was expected to make landfall in Canada on Saturday.

Most of Maine is currently under a tropical storm warning, Portland, Maine’s WMTW News reported. The storm currently has maximum sustained winds of 80 mph, the hurricane center said.

“The winds will increase through the day today, and tomorrow gusting as high as 75 mph,” Abrams said, as reported by CBS News. “Sunday, they’re going to start to taper off from the south to the north.”

More than three million people were under warnings and watches, Abrams said.

New England is still dealing with the aftermath of stormy weather that brought heavy rain, flooding and tornados, The Associated Press reported.

Tide and storm surge from Hurricane Lee are expected to cause more flooding along the New England Coast, reported NBC News. Forecasters said Cape Cod, Boston Harbor, Long Island Sound and other coastal areas were expected to get one to three feet of flooding, with one to two feet in parts of New York.

So far there have been five hurricanes and 14 named storms in 2023. Last month the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) said atmospheric and ocean conditions like record warm temperatures were expected to contribute to an “above normal” hurricane season.

“NOAA forecasters have increased the likelihood of an above-normal Atlantic hurricane season to 60% (increased from the outlook issued in May, which predicted a 30% chance),” the agency said in a press release issued last month.

The post ‘Large and Dangerous’ Hurricane Lee Heads for New England and Canada appeared first on EcoWatch.

Hurricane Lee, a mammoth peak-season storm in the Atlantic, is making a beeline for New England and Canada. Once a Category 5 storm, Lee weakened to Category 1 by the time it made a northward pivot and began its march toward land on Thursday. But the storm is still expected to lash parts of Massachusetts, Maine, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia with tropical-storm-force winds, rain, waves, and potentially catastrophic storm surge as it makes landfall over the weekend.

Meteorologists are especially concerned about the Bay of Fundy, a body of water between eastern Maine and Nova Scotia that holds the record for the highest tides in the world — with a difference of up to 53 feet between low and high tides. With a little bit of bad timing, Lee’s powerful winds could force a tremendous amount of water into the bay on top of a high tide, and inundate New Brunswick and Nova Scotia with record flooding.

Even on an ordinary day, the Fundy tides are so dramatic that they can sweep over whole beaches in a matter of minutes. In some parts of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, the incoming water at high tide pushes so far inland that it reverses the flow of rivers, a phenomenon known as a tidal bore.

“If the storm goes just west of the Bay of Fundy, and it’s aligned with the correct tide cycle — well, it’s an unfortunate science experiment,” said Jeff Berardelli, chief meteorologist for WFLA-TV in Tampa Bay, Florida. “We’ve never seen something like that exactly.”

Lee’s winds will be blowing west, which makes Nova Scotia, on the east side of the Bay of Fundy, particularly vulnerable to rising waters. There, waves could reach 40 feet in height on top of three to six feet of storm surge. “The water impacts, just exactly what’s going to happen there, that’s the big question mark,” said Ryan Truchelut, a meteorologist and the founder of the weather Substack WeatherTiger. “That’s potentially the most serious aspect of the storm.”

Storm surge could also be an issue on the north-pointing part of Cape Cod, Massachusetts. The National Hurricane Center has issued a storm surge watch for that portion of the cape.

Sixty-four-year-old Howard Zwicker owns the Harbour Grille & Gift House on Grand Manan Island, a small Canadian island between Maine and Nova Scotia at the wide mouth of the Bay of Fundy. On Thursday morning this week, he was unruffled by the forecast. “We’re cleaning up our yard, taking down our hanging plants and our patio furniture, and that’s pretty much it,” said Zwicker, who was born on Grand Manan Island and has run the Harbour Grille with his wife for the past decade. “Everybody is doing their due diligence, but nobody’s panicking.”

Storms of Lee’s intensity are not unusual in the northern Atlantic, though they rarely make landfall in New England and coastal Canada. Lee’s impacts will also be abnormal in a couple of respects. It’s a large weather system — the hurricane’s tropical force winds span roughly 600 miles in diameter — which means its effects will be felt in multiple states along the Eastern Seaboard.

“It’s gigantic,” said Truchelut. “In terms of tropical storm wind radii, this is one of the very largest out there.” Much of coastal New England will experience huge, battering waves that are 15 feet or higher. On Thursday, the governor of Maine issued a state of emergency as the state was put under its first hurricane watch in 15 years.

The other unusual thing about Lee is that the storm will bring flooding to a part of the U.S. that is already waterlogged from a summer so rainy it broke records in parts of New Hampshire and Vermont. This summer was Maine’s second wettest on record, behind the summer of 1917. Record-breaking rainfall is a telltale sign of climate change; research shows a hotter atmosphere holds more evaporated water.

Flooding brought on by Lee on top of the already soaked soil in New England will make the storm’s impacts more dangerous. Heavy gusts of wind can cause trees rooted in saturated soil to tip over, and localized flooding is more likely. “Fifty- or 60-mile-per-hour winds, you get that every year,” Truchelut said. “The difference here is that the trees still have their leaves on, and the soil is wet from recent rainfall.”

Climate change doesn’t create large hurricanes like Lee, but it does make them intensify faster and occur more frequently. The Atlantic Ocean is currently going through a period of extreme sea-surface warming — water temperatures in parts of the North Atlantic have hovered around 77 degrees Fahrenheit for more than a month, “almost beyond the most extreme predictions of climate models,” the Washington Post reported in July. That record warmth allowed Hurricane Lee to intensify from a tropical depression to a Category 5 storm in less than three days, a phenomenon that has only happened a couple of times before in Atlantic hurricane history.

“Given the record-high sea-surface temperatures in the North Atlantic, it is interesting that in this year we see a hurricane barreling toward New England,” said Sean Birkel, the state climatologist for Maine. “Because it is rare for hurricanes to reach New England and certainly into Maine.”

Lee is arriving at the meteorological midpoint of hurricane season, and there are multiple other storm systems on its tail. These include Margot, which is churning in the middle of the Atlantic, and a still-forming storm that could become Hurricane Nigel. Forecasts show Nigel taking the same path as Lee, west across the Atlantic Ocean and up past Bermuda. Even if the Northeast escapes major damage from Lee, it may not be out of the woods yet.

Jake Bittle contributed reporting to this article.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline ‘It’s gigantic’: Hurricane Lee heads for New England and Atlantic Canada on Sep 15, 2023.