These days, back-to-school shopping starts in May. And those school supplies lists the school sends…

The post How to Green Back-to-School Shopping appeared first on Earth911.

These days, back-to-school shopping starts in May. And those school supplies lists the school sends…

The post How to Green Back-to-School Shopping appeared first on Earth911.

This story was co-published with Popular Science.

Electric vehicles are becoming more and more commonplace on the nation’s roadways.

The federal government wants nearly two-thirds of all cars in the United States to be EVs within the next decade. All the while, EVs are breaking sales records, and manufacturers are building charging stations and production plants to incentivize a shift away from fossil fuels in the transportation sector.

With EVs taking the streets by storm, an unlikely industry now wants a piece of the pie.

Trade associations, fuel producers, and bipartisan lawmakers are pushing for biogas, fuel made from animal and food waste, to start receiving federal credits meant for powering electric vehicles.

The push for biogas-powered EVs would be a boon for the energy sector, according to biogas industry leaders. Environmental groups and researchers, however, say the fuel has yet to prove itself as a truly clean energy source. Biogas created from agriculture has been linked to an increase in waterway pollution and public health concerns that have disproportionately exposed low-income communities and communities of color to toxic byproducts of animal waste.

With the nation needing more ways to power fleets of Teslas and Chevy Bolts, the use of livestock manure to power EVs is still in limbo.

For biogas, there are, broadly speaking, three sources of waste from which to produce fuel: human waste, animal waste, and food waste. The source of this fuel input can be found at wastewater treatment plants, farms, and landfills.

At these locations, organic waste is deprived of oxygen, and a natural process known as anaerobic digestion occurs. Bacteria consume the waste products and eventually release methane, the main ingredient of natural gas. The gas is then captured, piped to a utility, turned into electricity, and distributed to customers.

Fuel created from animal waste isn’t a new concept. Farms around the country have been cashing in on biogas for decades, with a boom in production facilities known as anaerobic digesters expected after funding for their construction made it into the Inflation Reduction Act.

At the end of June, the Environmental Protection Agency finalized its Renewable Fuel Standard, or RFS, which outlines how much renewable fuels — products like corn-based ethanol, manure-based biogas, and wood pellets — are used to cut greenhouse gas emissions, as well as reduce the use of petroleum-based transportation fuel, heating oil, or jet fuel.

Under this program, petroleum-based fuels must blend renewable fuels into their supply. For example, each time the RFS is updated, a new goal for how much corn-based ethanol is mixed into the nation’s fuel supply is set. This prediction is based on gas and renewable-fuel-industry market projections.

These gas companies and refineries purchase credits from renewable-fuel makers to comply with the mandated amount of renewable fuel that needs to be mixed into their supply.

A currency system tracks which renewable fuels are being produced and where they end up under the RFS. This system uses credits known as RINs, or Renewable Identification Numbers. According to the EPA, a single RIN is the energy equivalent of one gallon of ethanol, and the prices of the credits will fluctuate over time, just as gas prices do.

Oil companies and refineries purchase credits from renewable-fuel makers to comply with the mandated amount of renewable fuel that needs to be mixed into their supply. The unique RIN credit proves that an oil seller has purchased, blended, and sold renewable fuel.

Currently, the biogas industry can only use its RIN credits when the fuel source is blended with ethanol or a particular type of diesel fuel. Outside of the federal program, biogas producers have been cashing in on low-carbon fuel programs in both California and Oregon.

With the boom in demand for renewable electricity, biogas producers want more opportunities to sell their waste-based fuels. EVs might get them there.

During recent RFS negotiations, the biogas industry urged the EPA to create a pathway for a new type of credit known as eRINs, or electric RINs. This pathway would allow the biogas and biomass industry to power the nation’s EVs directly. While the industry applauded the recent expansion of mandatory volumes of renewable fuels, the EPA did not decide on finalizing eRIN credits.

Patrick Serfass is the executive director of the American Biogas Council. He said the EPA could approve projects that would support eRINs for years, but has yet to approve the pathway for biogas-fuel producers.

“It doesn’t matter which administration,” Serfass said. “The Obama administration didn’t do it. The Trump administration didn’t do it. The Biden administration so far hasn’t done it. EPA, do your job.”

Late last year, the EPA initially included approval of eRINs in the RFS proposal. Republican members of Congress who sit on the Energy & Commerce Committee sent a letter to the EPA, saying that the RFS is not meant to be a tool to electrify transportation.

“Our goal is to ensure that all Americans have access to affordable, available, reliable, and secure energy,” the committee members wrote. “The final design of the eRINs program under the RFS inserts uncertainty into the transportation fuels market.”

The RFS has traditionally supported liquid fuels that the EPA considers renewable, the main of which is ethanol. Stakeholders in ethanol production see the inclusion of eRINs as an overstep.

In May, Chuck Grassley, a Republican senator from Iowa, introduced legislation that would outlaw EVs from getting credits from the renewable-fuels program. Grassley has been a longtime supporter of the ethanol industry; Iowa alone makes up nearly a third of the nation’s ethanol production, according to the economic growth organization Iowa Area Development Group.

Serfass said biogas is a way to offset the nation’s waste and make small and midsize farms economically sustainable, as well as local governments operating waste treatment plants and landfills. When it comes to animal waste, he said the eRIN program would allow farmers to make money off their waste by selling captured biogas to the grid to power EVs.

“There’s a lot of folks that don’t like large farms, and the reason that large farms exist is that as a society, we’re not always willing to pay $6 to $9 for a gallon of milk,” Serfass said. “You have farm consolidation so that farmers can just make a living.”

Initially, digesters were thought of as a climate solution and an economic boon for farmers, but in recent years, farms have stopped digester operations because of the hefty price tag to run them and their modest revenue. Biogas digesters are still operated by large operations, often with the help of fossil fuel companies, such as BP.

In addition to farms, Serfass said biogas production from food waste and municipal wastewater treatment plants would also be able to cash in on the eRIN program.

Dodge City, Kansas, a city of 30,000 in the western part of the state, is an example of a local government using biogas as a source of revenue. In 2018, the city began capturing methane from its sewage treatment and has since been able to generate an estimated $3 million a year by selling the fuel to the transportation sector.

Serfass said the city would be able to sell the fuel to power the nation’s EV charging grid if the eRIN program was approved.

The EPA’s decision-making will direct the next three years of renewable-fuel production in the country. The program is often a battleground for different industry groups, from biogas producers to ethanol refineries, as they fight over their fuel’s market share.

Of note, the biomass industry, which creates fuel from wood pellets, forestry waste, and other detritus of the nation’s lumber supply and forests, also wants to be approved for future eRIN opportunities.

This fuel source has a questionable track record of being a climate solution: The industry has been linked to deforestation in the American South, and has falsely claimed they don’t use whole trees to produce electricity, according to a industry whistleblower.

The EPA did not answer questions from Grist as to why eRINs were not approved in its recent announcement.

“The EPA will continue to work on potential paths forward for the eRIN program, while further reviewing the comments received on the proposal and seeking additional input from stakeholders to inform potential next steps on the eRIN program,” the agency wrote in a statement.

Ben Lilliston is the director of rural strategies and climate change at the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy. He said he supported the EPA’s decision to not approve biogas-created electricity for EVs.

“I think the jury is still out around biogas from large-scale animal operations about how effective they are,” Lilliston said.

He wants more independent studies to determine what a growing biogas sector under the eRIN program would mean for the rural areas and communities of color that surround these facilities.

Predominantly Black and low-income communities in southeastern North Carolina have been exposed to decades of polluted waters and increased respiratory and heart disease rates related to the state’s hog industry, which has recently cashed in on the biogas sector.

In Delaware, residents of the largely rural Delmarva peninsula have become accustomed to the stench of the region’s massive poultry farms. These operations now want to cash in on their waste with the implementation of more biogas systems in a community where many residents are Black or immigrants from Haiti and Latin America who speak limited English, according to the Guardian.

“I think that our concern, and many others’, is that this is actually going to increase emissions and waste and pollution,” Lilliston said.

Aaron Smith, a professor of agricultural economics at the University of California, Davis, said electricity produced from biogas could be a red herring when it comes to cheap, clean energy.

“There’s often a tendency to say, ‘We have this pollutant like methane gas that escapes from a landfill or a dairy manure lagoon, and if we can capture that and stop it from escaping into the atmosphere, that’s a win for the climate,’” Smith said. “But once we’ve captured it, should we do something useful with it? And the answer is maybe, but sometimes it’s more expensive to do something useful with it than it would be to go and generate that energy from a different source.”

Smith’s past research has found that the revenue procured by digesters has not been equal to the amount of methane captured by these systems. In a blog post earlier this year, Smith wrote that taxpayers and consumers are overpaying for the price of methane reduction. He found that the gasoline producers have essentially subsidized digester operations by way of the state’s low-carbon transportation standards. To pay for this, the gasoline industry offloads its increased costs by raising the price of gas for consumers.

“I think we do need to be wary about over-incentivizing these very expensive sources of electricity generation under the guise of climate games,” Smith told Grist.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline The new ethanol? Biogas producers are pushing livestock poop as renewable. on Aug 21, 2023.

This story was co-published with Rappler, a Philippines-based online news publication.

On a sunny June morning, Marilyn Lopez Capentes and Maylen Lopez push a metal cart through a narrow alleyway between modest homes in the Filipino city of Malabon, part of Metro Manila. Passing doorways adorned with plants growing out of plastic soda bottles, they stop at each household to gather waste, which they deposit into separate sacks for trash, recyclables, and organics, before rolling on.

All the corn cobs, egg shells, and mango peels Lopez and Capentes collect are destined for a nearby materials-recovery facility. There, the food scraps will be composted in towers of colorfully painted stacked tires and upright pipes, or fed into a blue plastic biodigester that powers a small gas burner nearby, on which the workers cook the rice for their lunch.

“In a waste-management scenario, once you address the organics, most likely you’re already addressing 50 to 60 percent of the waste problem,” explained Rap Villavicencio, a program manager at Mother Earth Foundation, the nonprofit that spearheaded the system at play.

Another 12 to 20 percent is recyclables, he said, which means this deceptively simple approach can keep up to 80 percent of waste out of landfills. And it comes with tangible benefits for Malabon residents: Less trash in the streets and gutters means less flooding and fewer odors, and the program has created local green jobs to boot.

It’s the success of this model that inspired GAIA, a nonprofit focused on alternatives to waste incineration, to connect Mother Earth Foundation with the Breathe Free Detroit campaign in Detroit, Michigan, which was established in 2015 to fight a nearby waste incinerator.

Though the groups have different primary focuses, they’re both fighting pollution that harms their communities. Mother Earth Foundation created a grassroots waste-management solution so effective it influenced the local government. That experience positioned it to offer guidance to Breathe Free Detroit, which is advocating for the community it represents to have more agency over how their waste is managed, too.

For more than two years now, representatives from each have been meeting regularly via Zoom to encourage one another, share best practices for countering neglect and fighting bad actors, and glean new ideas from what’s worked for their peers on the other side of the globe in a unique cross-cultural exchange.

“Looking at the success of the Mother Earth Foundation’s efforts in creating a decentralized multiscale composting system, we wanted to make that work here in the city of Detroit,” said KT Andresky, the campaign organizer at Breathe Free Detroit.

Founded in 1998, Mother Earth Foundation was started by a group of mothers in Quezon City, seven miles from Malabon, who were frustrated by delayed garbage collection in their neighborhood.

Over the next 25 years, the nonprofit lobbied for the 1999 Clean Air Act, which regulates activities that cause air pollution, and the 2000 Ecological Solid Waste Management Act, mandating the adoption of systematic waste management. The nonprofit soon emerged as a leader in zero-waste practices in the Philippines and the Asia Pacific region more broadly.

In 2013, the organization turned its attention to San Agustin, a barangay — the smallest political unit in the Philippines, analogous to a ward or district — in Malabon. The barangay had insufficient infrastructure in place to deal with residents’ waste, and as a result, most household trash was taken to an open dump site in a nearby empty lot or left to fester in the streets.

Besides being unsanitary and unpleasant to live around, all that trash posed a flood risk. As a low-lying barangay near Manila Bay flanked by the Navotas River on one side and the Tullahan River on the other, the area has long been prone to inundation during typhoon season, which is intensifying in the Philippines, one of the nations most vulnerable to climate change. But the trash problem in San Agustin compounded flooding even further, clogging the drains and gutters that would’ve allowed some of the water to drain off the streets.

The community-led waste-management program Mother Earth Foundation helped implement, wherein local waste workers walk the alleys with a cart every day to collect household waste and bring it to a facility where the majority of it can be composted or recycled, has made a noticeable difference.

“They no longer have to put their waste in the street,” said Ranz Lebria, a program officer at Mother Earth.

It was hard at first to convince the community to separate out their organic waste for collection when there wasn’t a clear financial return, the way there is for sorting out recyclables like plastic.

But 10 years into the program, San Agustin residents “have a positive outlook,” she said, and are proud of how clean the system keeps their community. While the foundation funded the early efforts, barangay leaders have seen the benefits clearly enough that they now contribute local government funding to maintain the facilities and pay the waste workers.

Breathe Free Detroit is a campaign that was created in 2015 by a handful of Detroit-based environmental organizations to join the long fight against the euphemistically named Detroit Renewable Power. The waste incinerator spewed toxic particulate matter, including cancer-causing dioxins, into the nearby East Side, a primarily Black community, for decades.

“Having a facility like that running for 33 years completely devastated the neighborhood that I live in,” said Andresky. “A lot of businesses and families left. Many schools shut down.”

She recounted hearing of a family whose athlete kids were plagued by asthma once they moved to the neighborhood, and whose symptoms resolved once they moved away. “There was huge disinvestment in this neighborhood, because it pretty much was a toxic place to live,” she added.

After years of campaigning from Breathe Free and other advocacy groups, the incinerator finally shut down in 2019, which many counted as a win. But residents are still living with the health consequences in the form of “rare cancers” and genetic disorders, she said.

“We lost a lot of neighbors to COVID because of the preexisting condition. We still live with those toxins in our bodies and our lungs and our blood.”

Some East Side residents began composting “as an act of resistance” while the incinerator was still up and running, and Andresky said that interest has increased since its shutdown, as residents are “really protective” of their clean air. By composting locally in backyards and vacant lots, she said, they can reduce the number of exhaust-spewing garbage trucks passing through the neighborhood, which will save the city money and keep the air cleaner.

That’s where Mother Earth Foundation comes in. The two organizations were introduced in 2020 via GAIA, a global nonprofit network they’re both members of. GAIA also connected them to an opportunity through C40 Cities, a global network of mayors working on climate solutions, to receive stipends for their time and participation in the partnership.

Breathe Free Detroit’s members were eager to learn from Mother Earth’s expertise with composting in a mix of rural and urban settings, which Andresky said parallels Detroit’s landscape dotted with urban farms. Leaders from both groups began meeting regularly on Zoom to talk about multiscale composting efforts as Breathe Free Detroit began its own compost pilot. And after two years of Zoom calls, the two organizations finally got to visit each other in person — reps from Breathe Free came to the Philippines in January, and Mother Earth leaders traveled to Detroit in April.

Andresky’s main takeaways from the relationship have been about how to get “multiscale, decentralized composting” up and running.

She wants to see systems like the one in San Agustin that make use of hyperlocal composting sites rather than relying on a big industrial operation, especially since there are so many urban farms in Detroit that could benefit from keeping those nutrients cycling in local soil. To that end, Breathe Free Detroit is currently working on a composting pilot, in the hopes that it will prove to the city that backyard and community composting are worth investing in.

“A municipal pickup of food waste that is trucked in and trucked out hundreds of miles is not the best zero-waste system,” she said, “and if we’re starting from scratch here in Detroit, we should really establish the best system.”

Breathe Free Detroit is returning the favor and offering lessons from its community experience, too. Though the Philippines was the first nation in the world to ban waste incinerators outright as part of the country’s Clean Air Act, companies from Europe and Japan have used alternate terms like “waste to energy” or “gasification” when describing their facilities to exploit loopholes in the law and build plants in the country anyway.

The same companies are also pushing to amend the law in question, which Villavicencio sees as tantamount to an admission of guilt — if what these facilities are doing really isn’t incineration, he argues, there would be no push to change the law in the first place.

“It’s a human rights issue. Incinerators are placed mostly in marginalized communities,” he said. “In our case in the Philippines, it’s in the areas of Indigenous people. It’s environmental discrimination.”

On her trip to Manila, Andresky took a detour with Mother Earth representatives to the city of Dumaguete, where a new “gasification” facility recently opened, to try to communicate the urgency of the negative health impacts that accompany living near an incinerator. Her message was very different from the ones locals had been hearing on the radio from politicians, who promised that having an incinerator nearby would be harmless.

“What we’ve learned from Detroit is that it’s hard to stop the incinerator once it’s built already,” said Villavicencio. “And the consequences really are worse [than you’d think], especially when you see it in person.”

The work is far from done, either in the cities Mother Earth works with in the Philippines or in Breathe Free’s part of Detroit. In the former, there’s a long road ahead to push back against the weakening of the incinerator law, and to bring the composting and waste-management systems that have been working well in San Agustin to more barangays. And in Detroit, more organizing is needed to ensure a “just transition for residents” so that the shutdown of the incinerator doesn’t lead to gentrification that pushes original residents out.

Through it all, though, both communities know that they have solidarity from their colleagues on the other side of the globe. Though the formal program that brought them together has officially ended, Villavicencio and Andresky expect their organizations to stay in touch.

“It’s been a great experience, and hopefully there’ll be more international collaborations like this,” said Villavicencio.

The whole thing has assured him that it’s not just “Western countries who provide technologies or tools to the developing countries,” he adds. “It should be a two-way knowledge exchange.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How 2 communities, separated by an ocean, are working together to manage trash better on Aug 21, 2023.

This story was originally published by Borderless.

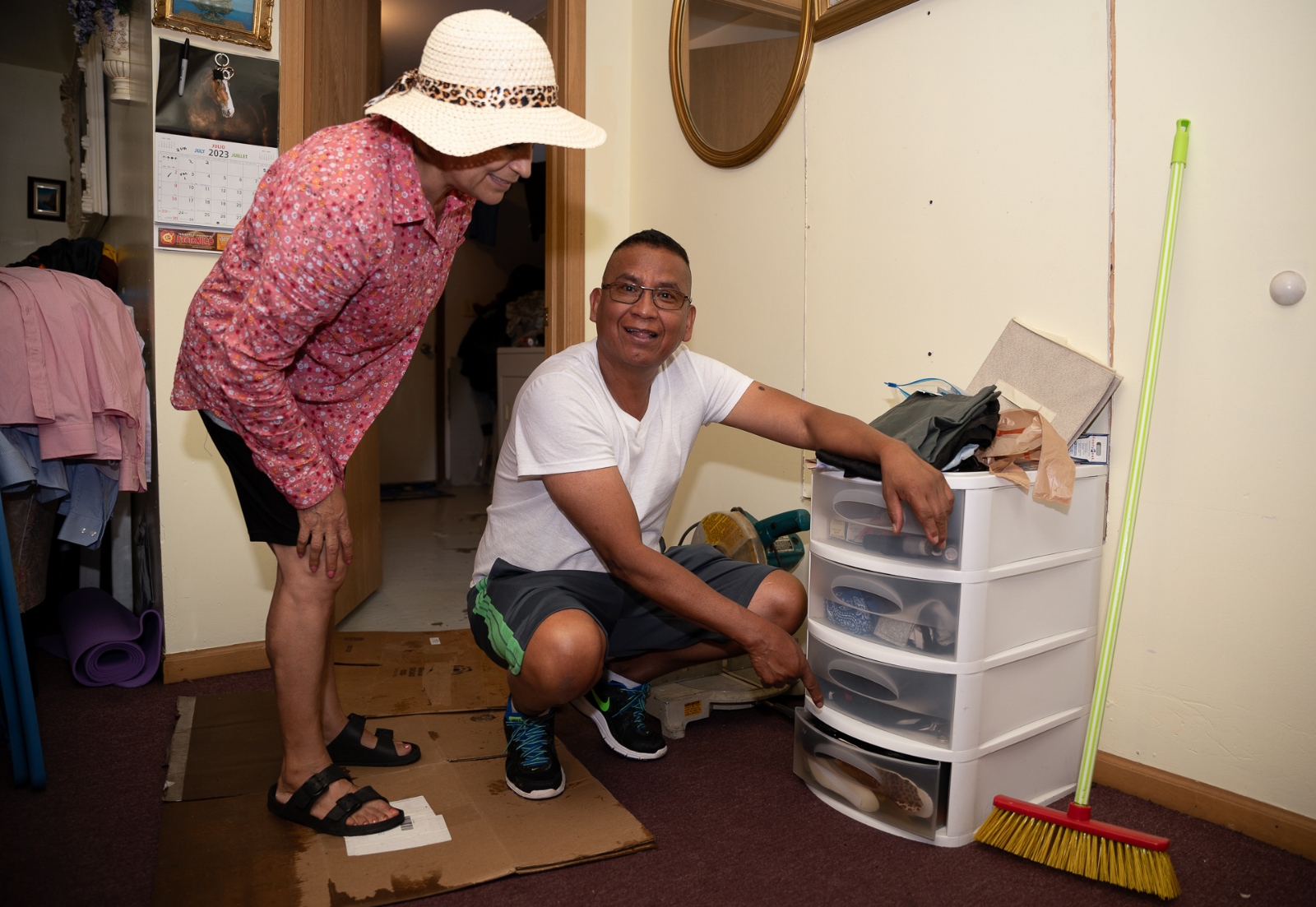

The day before Independence Day, the summer sun beat down on dozens of clothes and shoes strewn across the backyard and fence of the Cicero, Illinois, home where Delia and Ramon Vasquez have lived for over 20 years.

A nearly nine-inch deluge of rain that fell on Chicago and its suburbs the night before had flooded their basement where the items were stored in plastic bins. Among the casualties of the flood were their washer, dryer, water heater and basement cable setup. The rain left them with a basement’s worth of things to dry, appliances and keepsakes to trash, and mounting bills.

The July flood was one of the worst storms the Chicago region has seen in recent years and over a month later many families like the Vasquezes are still scrambling for solutions. Without immediate access to flood insurance, the couple was left on their own to deal with the costs of repairing the damage and subsequent mold, Delia said. The costs of the recent flood come as the Vasquez family is still repaying an $8,000 loan they got to cover damages to their house from a flood in 2009.

Aggravated by climate change, flooding problems are intensifying in the Chicago region because of aging infrastructure, increased rainfall and rising lake levels. An analysis by Borderless Magazine found that in Chicago and its surrounding suburbs, extreme weather events and heavy rainfall disproportionately affect people of color and those from immigrant backgrounds. These same communities often face barriers to receiving funding for flood damage or prevention due to their immigration status – many undocumented people cannot get FEMA assistance – as well as language or political barriers.

“You feel hopeless because you think the government is going to help you, and they don’t,” Delia said. “You’re on your own.”

The lack of a political voice and access to public services has been a common complaint in Cicero, a western suburb of Chicago where Latinos account for more than four out of five residents, the highest such percentage among Illinois communities.

One potential solution for communities like Cicero could come from Cook County and the Center for Neighborhood Technology (CNT) in the form of their RainReady program, which links community input with funding for flood prevention. The program has already been tried out in a handful of suburbs and is now being implemented in the Calumet region, a historically industrial area connected by the Little Calumet River on the southern end of Cook County. The RainReady Calumet Corridor project would provide towns with customized programs and resources to avoid flooding. Like previous RainReady projects, it relies on nature-based solutions, such as planting flora and using soil to hold water better.

CNT received $6 million from Cook County as part of the county’s $100 million investment in sustainability efforts and climate change mitigation. Once launched, six Illinois communities — Blue Island, Calumet City, Calumet Park, Dolton, Riverdale and Robbins — would establish the RainReady Calumet Corridor.

At least three of the six communities are holding steering committee meetings as part of the ongoing RainReady Calumet process that will continue through 2026. Some participants hope it could be a solution for residents experiencing chronic flooding issues who have been left out of past discussions about flooding.

“We really need this stuff done and the infrastructure is crumbling,” longtime Dolton resident Sherry Hatcher-Britton said after the town’s first RainReady steering committee meeting. “It’s almost like our village will be going underwater because nobody is even thinking about it. They might say it in a campaign but nobody is putting any effort into it. So I feel anything to slow [the flooding] — when you’re working with very limited funds — that’s just what you have to do.”

In Cicero and other low-income and minority communities in the Chicago region where floods prevail, the key problem is a lack of flood prevention resources, experts and community activists say.

Amalia Nieto-Gomez, executive director of Alliance of the Southeast, a multicultural activist coalition that serves Chicago’s Southeast Side — another area with flooding woes — laments the disparity between the places where flooding is most devastating and the funds the communities receive to deal with it.

“Looking at this with a racial equity lens … the solutions to climate change have not been located in minority communities,” Nieto-Gomez said.

CNT’s Flood Equity Map, which shows racial disparities in flooding by Chicago ZIP codes, found that 87 percent of flood damage insurance claims were paid in communities of color from 2007 to 2016. Additionally, three-fourths of flood damage claims in Chicago during that time came from only 13 ZIP codes, areas where more than nine out of 10 residents are people of color.

Despite the money flowing to these communities through insurance payouts, community members living in impacted regions say they are not seeing enough of that funding. Flood insurance may be in the name of landlords who may not pass payouts on to tenants, for example, explains Debra Kutska of the Cook County Department of Environment and Sustainability, which is partnering with CNT on the RainReady effort.

Those who do receive money often get it in the form of loans that require repayment and don’t always cover the total damages, aggravating their post-flood financial difficulties. More than half of the households in flood-impacted communities had an income of less than $50,000 and more than a quarter were below the poverty line, according to CNT.

CNT and Cook County are looking at ways to make the region’s flooding mitigation efforts more targeted by using demographic and flood data on the communities to understand what projects would be most accessible and suitable for them. At the same time, they are trying to engage often-overlooked community voices in creating plans to address the flooding, by using community input to inform the building of rain gardens, bioswales, natural detention basins, green alleys and permeable pavers.

Midlothian, a southwestern suburb of Chicago whose Hispanic and Latino residents make up a third of its population, adopted the country’s first RainReady plan in 2016. The plan became the precursor to Midlothian’s Stormwater Management Capital Plan that the town is now using to address its flooding issues.

One improvement that came out of the RainReady plan was the town’s Natalie Creek Flood Control Project to reduce overbank flooding by widening the channel and creating a new stormwater storage basin. Midlothian also installed a rain garden and parking lot with permeable pavers not far from its Veterans of Foreign Wars building, and is working to address drainage issues at Kostner Park.

Kathy Caveney, a Midlothian village trustee, said the RainReady project is important to the town’s ongoing efforts to manage its flood-prone creeks and waterways. Such management, she says, helps “people to stop losing personal effects, and furnaces, and water heaters and freezers full of food every time it rains.”

Like in the Midlothian project, CNT is working with residents in the Calumet region through steering committees that collect information on the flood solutions community members prefer, said Brandon Evans, an outreach and engagement associate at CNT. As a result, much of the green infrastructure CNT hopes to establish throughout the Calumet Corridor was recommended by its own community members, he said.

“We’ve got recommendations from the plans, and a part of the conversation with those residents and committee members is input on what are the issues that you guys see, and then how does that, in turn, turn into what you guys want in the community,” Evans said.

The progress of the RainReady Calumet Corridor project varies across the six communities involved, but final implementation for each area is expected to begin between fall 2023 and spring 2025, Evans said. If the plan is successful, CNT hopes to replicate it in other parts of Cook County and nationwide, he said.

Despite efforts like these, Kevin Fitzpatrick of the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District argues that the scale of the flooding problem in the Chicago region is so large that a foolproof solution would be “prohibitively expensive.” Instead, communities should work toward flood mitigation with the understanding that the region will continue to flood for years to come with climate change. And because mitigation efforts will need to be different in each community, community members should be the ones who decide what’s best for them, says Fitzpatrick.

In communities like Cicero, which has yet to see a RainReady project, local groups have often filled in the gaps left by the government. Cicero community groups like the Cicero Community Collaborative, for example, have started their own flood relief fund for residents impacted by the early July storm, through a gift from the Healthy Communities Foundation.

Meanwhile, the Vasquez family will seek financial assistance from the town of Cicero, which was declared a disaster area by town president Larry Dominick and Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker after the July storm. The governor’s declaration enables Cicero to request assistance for affected families from FEMA.

But the flooding dangers persist.

The day after her home flooded, a neighbor suggested to Delia Vasquez that she move to a flood-free area. Despite loving her house, she has had such a thought. But like many neighbors, she also knows she can’t afford to move. She worries about where she can go.

“If water comes in here,” Vasquez said, “what tells me that if I move somewhere else, it’s not going to be the same, right?”

Efrain Soriano contributed reporting to this story.

This piece is part of a collaboration that includes the Institute for Nonprofit News, Borderless, Ensia, Grist, Planet Detroit, Sahan Journal and Wisconsin Watch, as well as the Guardian and Inside Climate News. The project was supported by the Joyce Foundation.

Editor’s Note: As noted above both this project and the Center for Neighborhood Technology receive funding from Joyce Foundation. Borderless also receives funding from the Healthy Communities Foundation. Our news judgments are made independently — not based on or influenced by donors.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline A community-led approach to prevent flooding expands in Illinois on Aug 20, 2023.

This story was produced by the nonprofit journalism publication Capital and Main and is republished with permission.

Environmental groups, faculty associations, and others seeking to slow climate change are pushing California to cut its investments in fossil fuels. Divestment supporters point to the state’s massive economy — the largest in the country — as evidence that divesting here could help kick off a nationwide trend by hurting fossil fuel companies and accelerating the transition to clean energy.

They’ve had little success. A recent divestment bill that would have directed managers of California’s public pension and teachers’ retirement funds to stop investing in the 200 largest oil, gas, and coal companies failed in the Legislature for the second year in a row. State pension funds have an estimated $14.8 billion invested in fossil fuel companies that are driving the climate crisis.

SB 252 would require the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) and the State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) to sell their remaining fossil fuel investments by the 2030s.

Supporters of divestment say their goal is to “delegitimize fossil fuel companies as political players.”

For the second time in two years, the bill was blocked by a single legislator heading the Assembly’s Committee on Public Employment and Retirement. It will be up for reconsideration next year.

In a statement to Capital & Main, Assemblymember Tina McKinnor (D-Inglewood), the committee chair who blocked the bill, said she wanted to learn more about how divestment could affect pensioners in the state. In her campaign for office last year, labor unions were her largest supporters, contributing at least $358,900. She also benefited from more than $100,000 put up by a political action committee funded by oil and gas companies.

“Before making a decision on this policy, I have asked CalPERS and CalSTRS members, beneficiaries, and their labor representatives to share their opinion on this legislation. These funds pay for their retirement and I welcome their voices before considering SB 252 in 2024,” McKinnor said.

The bill was carried, once again, by Sen. Lena Gonzalez (D-Long Beach). Her press secretary, Leoda Valenzuela, said that McKinnor agreed to hold an “informational hearing” in early 2024.

Board members and staff from CalPERS met with lawmakers to lobby against it. A CalSTRS spokesperson said the fund’s staff expressed their opposition to McKinnor and other legislators.

California’s pensions are holding onto fossil fuel investments just as the severe effects of the climate crisis bear down on the world. The previous months were Earth’s hottest in perhaps 125,000 years, a direct result of interactions between global warming and the cyclical warm-weather pattern called El Niño. Other effects linked to rising heat, like disastrous wildfires, downpours, and drought, are occurring at an overwhelming pace across the U.S. and the world.

The window to meet the target for international climate emissions cuts is shrinking, raising the likelihood of a worsening crisis now and in the future. Scientists say that to limit damage, fossil fuels must be phased out as fast as possible while the world transitions to renewable forms of energy such as solar, wind, geothermal, and other less-polluting sources.

Divesting California’s pensions would be a small hit to an industry worth trillions, but the actions could reverberate around the globe and inspire similar actions elsewhere. Other institutions, worth $40.51 trillion in total, have divested or pledged to divest from oil, gas and coal.

They include Harvard University and pension funds outside the U.S. A majority of those that have divested or pledged to divest are faith-based organizations, philanthropic groups, and universities. More than two dozen American cities, mostly in California, have sold their fossil fuel assets and committed to not buying any more. The Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero, a coalition of asset owners and banks that supports decarbonization, has said that divestment should accompany policies to fight climate change.

California’s state pension funds warn that divestment could result in some short-term hits to workers’ retirement funds. They’ve argued the losses for CalPERS pensions could amount to more than $300 million a year. The funds have already divested from other securities related to tobacco, private prisons, some forms of coal and regimes in Iran and Sudan, resulting in a $9.55 billion loss for pensions for CalSTRs alone.

In response, supporters cite an analysis that found the funds lost almost $10 billion due to poorly performing fossil fuel holdings over the last decade. Losses may accelerate if companies start abandoning assets, like refineries and millions of wells. In addition, both pension funds rely on investment models that are likely underestimating the costs of climate damage on pensioners’ portfolios, according to a report from Carbon Tracker.

The pension funds have said that instead of divesting, they can use their leverage as investors to nudge companies toward renewable energy. CalPERS also recently committed to increasing its investments in renewable energy compared to fossil fuels. Another concern expressed by opponents of the tactic is that it’s possible and even plausible that divesting would hand off the assets to others who have less stringent policies on emissions.

So far, oil majors haven’t promised to end fossil fuel production, a key requirement if they want to help the world halt global warming. And sometimes they’ve resisted pressure from investors. For example, after CalSTRS joined other investors to elect climate-conscious board directors at ExxonMobil, the company fought against efforts to create change.

Dan Cohn, global energy transition researcher at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, said there’s little evidence to back up the idea that investors can steer fossil fuel companies onto the right path.

“The pensions say if they don’t invest in these assets, unscrupulous people will have a seat at the table and that will be bad,” Cohn said. “What is the evidence that having a seat at the table has any perceptible impact on a company’s trajectory as a main source of fossil fuels in the world?”

Other states where pensions divested have faced political backlash.

A lawsuit, filed in May by a group that opposes public sector unions, alleges that three New York City pension funds are engaged in a “misguided and ineffectual gesture to address climate change” after they sold polluting assets worth about $3 billion.

And Maine’s law requiring its pensions funds to divest allows them to hold fossil fuels if doing otherwise would result in losses. Even so, it became a political lightning rod. A Republican candidate for governor bashed the policy repeatedly while campaigning last year.

Besides McKinnor’s refusal to hear the bill, there are signs that California’s political leadership fears a similar backlash.

Before SB 252 passed the State Senate, six Democratic senators had “no vote recorded” on the bill. This is a tactic some lawmakers use to avoid upsetting powerful interests without sullying their record on the environment and climate.

But with the reality of climate change now clear, divestment could grow as a tactic. Even the United Nations’ leading architect of the Paris Agreement, the 2015 global plan to cut emissions, recently admitted that fossil fuel companies cannot be trusted to help the world fight the crisis — a major about-face.

Young people staring down a hotter, water-scarce future where catastrophes are the norm have long been a driving force behind divestment.

Anaya Sayal, a 16-year-old member of Youth vs. Apocalypse, said in a statement the bill “brings us one step closer to living in a world where we don’t have to live in a constant state of apprehension regarding health conditions, and issues we face because of climate chaos; that future generations will also face as a result of the climate catastrophe.”

Copyright 2023 Capital & Main

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline One person stopped California’s divestment from fossil fuels — again on Aug 19, 2023.

According to a new University of Massachusetts Amherst (UMass Amherst) study, Americans whose income is in the top 10 percent are responsible for 40 percent of the total greenhouse gas emissions in the country. It’s the first study to connect income with the emissions used to generate it.

The researchers focused on earnings derived from financial investments and recommended taxes be adopted that hone in on investment incomes’ carbon intensity, a press release from UMass Amherst said.

“Current policies to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and increase adaptation and mitigation funding are insufficient to limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C. It is clear that further action is needed to avoid the worst impacts of climate change and achieve a just climate future,” the authors of the study wrote. “We find significant and growing emissions inequality that cuts across economic and racial lines. In 2019, fully 40% of total U.S. emissions were associated with income flows to the highest earning 10% of households. Among the highest earning 1% of households (whose income is linked to 15–17% of national emissions) investment holdings account for 38–43% of their emissions.”

Human consumption like driving vehicles, eating particular types of food and buying certain kinds or an excess of goods is a long-established generator of greenhouse gas emissions, the press release said.

Environmental policy has tended to focus on limiting consumption or directing it toward things that have less of a carbon footprint, like driving an electric vehicle or eating plant-based food.

“But consumption-based approaches to limiting greenhouse gas emissions are regressive,” said Jared Starr, a sustainability scientist at UMass Amherst and lead author of the study, in the press release. “They disproportionately punish the poor while having little impact on the extremely wealthy, who tend to save and invest a large share of their income. Consumption-based approaches miss something important: carbon pollution generates income, but when that income is reinvested into stocks, rather than spent on necessities, it isn’t subject to a consumption-based carbon tax. What happens when we focus on how emissions create income, rather than how they enable consumption?”

The study, “Income-based U.S. household carbon footprints (1990–2019) offer new insights on emissions inequality and climate finance,” was published in the journal PLOS Climate.

In the study, the research team examined three decades’ worth of data from 1990 to 2019, first from a database of 2.8 billion financial transfers and their intersectoral flow of income and carbon.

From this information, the researchers were able to calculate two separate values: one that represented producer-based income from greenhouse gas emissions and one representing supplier-based emissions, which are created by industrial suppliers of fossil fuels.

As an example, operating fossil fuel companies doesn’t produce an enormous amount of emissions, but they make a huge amount of profit selling the oil to those who will end up burning it and producing emissions.

Emissions that are producer-based, on the other hand, are those released by operating the business, as with coal-fired power plants.

Using their two main calculations, the research team linked them with a database containing income and demographic data for more than five million people in the U.S. The database separates active sources of income, like wages and salaries, from passive sources of investment income.

“This research gives us insight into the way that income and investments obscure emissions responsibility,” Starr said in the press release. “For example, 15 days of income for a top 0.1% household generates as much carbon pollution as a lifetime of income for a household in the bottom 10%. An income-based lens helps us focus in on exactly who is profiting the most from climate-changing carbon pollution, and design policies to shift their behavior.”

The team not only discovered that more than 40 percent of emissions in the U.S. could be attributed to income earned by the top 10 percent, but that those with earnings in the top one percent generated 15 to 17 percent of the emissions in the country.

The researchers also found that, for the most part, the income linked to the highest emissions came from white, non-Hispanic households, while Black households had the lowest emissions-linked income.

Fossil fuel emissions also had a tendency to increase with age, peak within the 45 to 54 age group, then decline.

“Consumer-facing carbon taxes would hit poor Americans hardest because the emissions intensity of their purchases tends to be higher than higher-income groups because they’re buying things related to necessities,” while higher-income groups tend to spend more on services, Starr told The Hill. “These low-income groups basically spend all that comes in, whereas as you move up the income ladder, the higher-income groups have really high savings rates, [and] money that they save or re-invest are not reflected in consumer-facing carbon taxes.”

The team found that “super emitters” were almost only found among households in the top 0.1 percent of earners, consisting mostly of those in real estate, finance, manufacturing, insurance, mining and quarrying.

Starr and the other researchers suggested taxing shareholders and income, rather than consumer products.

“In this way,” Starr said in the press release, “we could really incentivize the Americans who are driving and profiting the most from climate change to decarbonize their industries and investments. It’s divestment through self-interest, rather than altruism. Imagine how quickly corporate executives, board members and large shareholders would decarbonize their industries if we made it in their financial interest to do so. The tax revenue gained could help the nation invest substantially in decarbonization efforts.”

The post Wealthiest 10% of Americans Responsible for 40% of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Study Finds appeared first on EcoWatch.

Overfishing occurs when fish are caught faster than their populations can reproduce and replenish themselves, and it’s among the greatest threats to our oceans. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, one-third of assessed fisheries worldwide are pushed beyond their biological limits, which has severe environmental and social consequences.

While overfishing can occur in any aqueous habitat — oceans, lakes, ponds, rivers, and wetlands alike — it is especially associated with commercial fishing in marine waters, whereby massive numbers of fish are caught at once. Some trawl nets used in ocean fishing are so big, they can hold up to 13 jumbo jets. Today, nearly 90% of marine fish stocks (a stock being defined as a group of the same species that lives in the same geographic area) globally are either overfished or exploited.

Fishing itself has happened throughout recorded history, but deep-sea, commercial fishing didn’t arise until the 15th century, and became more commercial in the 19th century with the arrival of steamboats. Around that time, humans began destroying whale populations as they fished them in huge numbers for their blubber to make oil.

In the 1950s, this type of intensive fishing ceased to be an industry that characterized only a few areas, but extended to the vast majority of fisheries. The 1970s brought the first major signs of overfishing and became clearer in the 1990s when populations of open sea fish started falling dramatically, and Atlantic cod, herring, and California sardines were fished almost to extinction. Canada’s Grand Banks cod fishery collapsed in 1992, leading to massive layoffs in coastal communities and exposing the immediate threat of overfishing.

The term “overfishing” refers specifically to fishing beyond sustainable levels, although illegal and destructive fishing often play a role in population depletion.

It’s important to note that overfishing is not the same as illegal fishing. Overfishing is often not illegal, and occurs when there are inadequate catch limits, a lack of standards set by governments, or other management issues. Illegal fishing, on the other hand, entails fishing without a license, with illegal gear, in closed areas, over a set quota, or of prohibited species. It’s often called IUU fishing (Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated), and breaks either regional or international laws. Illegal fishing operations are estimated to be worth about $10-23.5 billion annually, according to the Marine Stewardship Council, although much of this activity goes unreported. Total catches in West Africa, for example, are purported to be about 40% more than what is reported. Illegal operations often do not adhere to sustainability standards, and thus cause damage to fish populations and marine ecosystems.

Destructive fishing is also a separate kind of harmful fishing. The term refers to practices that are harmful to fish populations and their habitats based on certain highly destructive methods, like the use of cyanide or explosives. Blast fishing, for one, uses explosives to stun the fish and raise them to the surface of the water, destroying entire sections of coral reefs and other ecosystems in the process. Cyanide fishing — which is practiced widely in Southeast Asia — uses the chemical to stun coral reef fish in order for fishers to capture them alive (although one-third to one-half of fish caught by this method usually die), but corals are seriously damaged in the process of extracting the stunned fish, and by the cyanide itself.

The causes of overfishing are manyfold and complex, with multiple factors compounding and contributing to the problem.

Fishing is no longer the imprecise, uncertain practice that it once was. Technological advances — like satellite navigation, echo-sounders, and acoustic cameras — have made it easier for fishers to locate fish and capture them with great precision. Huge, commercial fishing vessels also have refrigeration systems on board, which makes it possible for boats to stay out at sea for longer and catch greater volumes of fish at once.

Quite simply, there are more people in the world, and so a greater demand for fish. Marine fish provide about 15% of all animal protein consumed by humans, but as populations grow, so does the number of fish needed to satisfy demand. The average increase of global fish consumption has actually outpaced population growth, meaning people are also consuming more fish on average. Between 1990 and 2018, consumption of seafood rose 122%, and as it’s grown, the level of sustainable fish stocks has dropped by about a third from 1970s levels.

Governmental support is cited as a reason why overfishing continues. Currently, annual subsidies to marine fisheries globally are around $35 billion — that’s about 30% of the first sale value of all caught fish. This financial support (sometimes in the form of lower taxes) that’s given to the fishing industry offsets the costs of doing business, incentivizes the catching of fish beyond sustainable levels, and encourages companies to continue fishing in overexploited areas where they would otherwise be unsuccessful. Subsidies are also an issue of equity in the sector — they are usually given to huge industrial fisheries and not smaller ones run by local people in places like coastal west Africa and the south Pacific, so the locals are forced to compete with these larger, subsidized companies.

Fisheries can be managed by governments either locally, regionally, nationally, or internationally, but are sometimes managed poorly with few barriers in place to prevent overfishing. Proper management will consider research on the state of fish stocks and how to sustain their populations, and usually institute catch quotas and other requirements for fisheries. But many fisheries are governed poorly and allow for too much fishing, or have inadequate reporting, monitoring, or enforcement systems that enable exploitation of the stocks.

Oceans cover 70% of the Earth’s surface, but less than 8% (roughly the size of North America) of the ocean is protected. Marine Protected Areas have limits on human activity, but it’s a broad term that could mean many things; some have restricted visitation, allow for sustainable use by indigenous populations, and or even allow for commercial fishing. In fact, 80% of protected ocean areas still allow fishing within their borders. To properly restore biodiversity, a 2021 study suggests that 30% of oceans needs to be protected.

Overfishing poses a huge threat to marine environments, from declining fish populations, to habitat destruction, to ocean pollution, and even the acceleration of climate change.

When fishery stocks fall below biologically sustainable levels, populations suffer and are at risk of becoming either endangered or extinct. Among the most overfished species are Southern and Atlantic bluefin tuna, European eel, cod, swordfish, groupers, and sturgeons. Currently, only 3% of Pacific bluefin tuna remain based on the population’s historic levels. Overall, marine species have decreased nearly 40% in the past 40 years.

When their populations shrink, fish have to adapt differently. They might change in size, reproduce differently, or mature on a different timeline. When fish are captured when they are too small — a phenomenon called “growth“ overfishing — they never make it to maturity and thus don’t reproduce as much, so the overall yield and population of the fish shrinks. “Recruitment“ overfishing occurs when the adult population is so depleted that there aren’t enough fish to produce offspring. Deep sea fish like orange roughy, for example, grow very slowly given the lack of resources on the ocean floor, often taking decades to reach breeding maturity — so when they are caught, it takes a very long time for their populations to replenish.

Overfishing not only threatens the species themselves, but also the ecosystems they live in — particularly already-threatened coral reefs. It has been found to be the most serious threat to coral reefs, and it’s predicted that 90% of global coral reefs will be dead by 2050 due to commercial fishing. Besides blast- and cyanide-fishing practices, reefs are also impacted by trawling (sometimes called “bottom dragging”), a fishing tactic of dragging large nets along the ocean floor to catch fish. When algae-eating species are overfished, algae can also propagate unchecked and eventually smother the coral it grows on.

Bycatch is closely tied to overfishing, and constitutes one of its largest environmental impacts. Because commercial fishing hauls in huge numbers of fish at once, unwanted fish and animals are often caught in the process and are then merely discarded. Unwanted (or “non-target” species) are swept up when trawling for large quantities of fish using indiscriminate, non-selective gear that captures all wildlife in its path, including other species of fish, sea lions, dolphins, turtles, sharks, and even sea birds. Bycatch is sometimes returned to the ocean, but the animals often die or are injured so severely that they cannot reproduce.

Billions of fish and hundreds of thousands of sea turtles and cetaceans are lost every year as bycatch, according to the World Wildlife Fund. Six out of seven species of sea turtles are either threatened or endangered as a direct result of fishing — they often get caught when fishers trawl for shrimp or prawns on the ocean floor, where turtles like to forage. Sharks are very susceptible, too, and about 50 million are killed every year as bycatch by unregulated fisheries. More than one-third of all sharks, rays, and chimaeras are now at risk for extinction due to overfishing alone.

A fishing practice called “longlining” — whereby a line is sent out with hundreds or sometimes thousands of baited hooks — results in a lot of bycatch. Longlining is usually employed to catch tuna, swordfish, and halibut, but other fish go after the hooks, too. Sea birds also get caught in the lines when they dive under the water to fish.

The removal of fished species and the death of bycatch can seriously impact marine trophic structures. Fish are a part of complex marine food chains, serving as food sources for larger fish and feeding on smaller fish or vegetation. Sharks, for example, are large predators that regulate smaller species below them, so when large numbers are lost as bycatch, smaller fish populations might grow too large. If there are unnaturally high numbers of fish, they might feed too heavily on vegetation that’s needed by other species, further impacting the ecosystem and causing a ripple effect through the food chain.

When fishers engage in huge fishing operations, they leave a lot of trash in their wake. Up to one million tons of fishing gear is abandoned in oceans every year, smothering animals, corals, and other marine habitats. This “ghost gear” makes up 10% of all ocean plastic pollution, but constitutes the majority of large plastic items. In terms of weight, 86% of plastic in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is fishing nets. Like other ocean plastics, this gear breaks down slowly over time, releasing microplastics into the ocean as it degrades.

Our oceans are carbon sinks, meaning they absorb carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere, effectively mitigating climate change. In all, the ocean absorbs 25% of our CO2 emissions and 90% of heat generated by humans. Fishing activity removes sequestered “blue carbon” from the ocean and releases it into the atmosphere.

Carbon is sequestered in the bodies of phytoplankton, which convert CO2 into sugars, but disrupting marine habitats and food webs impacts their activity. Carbon stored in the sediment of the seafloor is also released when bottom trawling disturbs its surface.

Besides the environmental impacts of overfishing, exploiting our oceans also impacts economies that depend on fishing for income, and communities that rely on fish as a source of protein.

The fishing industry is currently valued at $362 billion, and supplies income for 10-12% of the world population, from both large- and small-scale fishing operations. 60 million people globally work either directly or indirectly in the fishing industry, but if fish stocks are overexploited and can no longer be profitably harvested, many of these jobs could disappear. Coral reef areas are also tourism hubs for activities like snorkeling and boating. If these ecosystems are destroyed by trawling and destructive fishing, local communities that depend on tourism will also suffer.

Sustaining fish populations is also a matter of food security. Globally, 3 billion people depend on seafood as a protein source, especially in the Maldives, Japan, Iceland, Cambodia, and western coastal communities in Africa, all of which could face a food crisis if fish stocks drop so low that they cannot replenish themselves. Because of poorly managed fisheries, the Marine Stewardship Council estimates that 72 million more people every year are missing out on getting enough protein.

Fish farming (also called aquaculture) raises fish in captivity for consumption. The Southern bluefin tuna was first bred in captivity in 2009, and now about half of the fish eaten in the U.S. are farmed. Aquaculture is often touted as a solution to wild-caught fish, but it comes with its own set of issues. Carnivorous fish — like tuna and salmon — need to eat smaller fish in order to grow. So while these fish themselves are grown in farms, their prey are still being fished — often unsustainably — in order to feed them, merely displacing the problem. There are nutritional drawbacks to farmed fish as well. Wild fish get omega-3s (a fatty acid that is a main benefit of eating fish) from eating aquatic plants, which they don’t get in fish farms when fed a diet of corn and soy. A growing body of research suggests that, contrary to prior assumptions, fish do feel pain and stress, which are heightened when living in confined conditions.

There are, however, solutions to overfishing — both on the personal and the legislative level.

Subsidies make it possible for companies to keep fishing in overfished waters, even when these ventures become less profitable as fish populations decline. It’s widely understood that ending subsidies would be effective at preventing overfishing, as 54% of high-seas fishing grounds wouldn’t be profitable in their absence. The World Trade Organization made moves in 2022 to curb subsidies by securing the Fisheries Agreement, under which countries are working to ban subsidies to IUU fishing and overfished stocks.

Better management of fisheries could reduce overfishing, as could enforcement of rules, including catch limits/quotas, whereby only a predetermined amount of fish can be caught every year; catch-share programs, which distribute harvest allowances to companies or individuals, who can then either use or sell them; and gear restrictions that only allow for species-specific nets or other devices that prevent bycatch, like turtle excluder devices (TED) that allow megafauna and turtles to escape shrimp nets.

Small-scale fisheries in Japan and Chile have found success in using rights-based management. Under this system, exclusive ownership is given to a person, company, or municipality (like a village or community), which removes the tragedy-of-the-commons mentality and gives the owner an incentive to avoid overfishing the waters.

Technological advances have contributed to overfishing, but they might also offer a solution. The Global Environment Facility (GEF) and the FAO instituted a program in 2018 that promoted fish aggregating devices (FAD), which are essentially floating devices that lure fish rather than catch them with large nets. So far, the program has seen a successful reduction of bycatch in Pakistani fisheries. SafetyNet Technologies has also developed a method of using LED lighting on gear that changes color and intensity to evoke behavioral responses from fish, allowing them to target specific species. These are among the many technological innovations being explored to reduce bycatch and other harmful effects of commercial fishing.

Even with new technological solutions, legislation is needed to implement management strategies and ensure compliance. Legislation around overfishing in the United States has seen success in helping fish species rebound. The Magnuson-Stevens Act — which provided for the management of marine fisheries in U.S. waters — passed in 1976 and is credited with helping Atlantic sea scallop and haddock populations rebuild, but hasn’t been updated or reauthorized since 2006. The Seafood Import Monitoring Program (SIMP) managed by NOAA is a federal traceability standard, whereby importers have to report data about where fish were harvested for over a thousand different species. Before SIMP was implemented, almost a third of all wild-caught seafood imports to the U.S. were from illegal fishing operations. However, some environmental groups have argued that the program needs to be more stringent.

While some Pacific island nations have historically protected their oceans, the U.S. and European countries didn’t manage coastal fisheries until the 20th century. Only 8% of the ocean is currently classified as Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), which are protected along a spectrum: minimally, lightly, and highly/fully protected, which prohibits any kind of extractive activity (including drilling, mining, and fishing, aside from subsistence and recreational fishing under some circumstances). Science has shown that even under the best management by fisheries, an ocean ecosystem doesn’t receive all of the benefits of a fully protected MPA. Creating more MPAs would give species the chance to replenish within their borders. Ultimately, fisheries would benefit from these protections, too, as fish populations rebound within MPAs, and then often go back to fishing areas — a phenomenon referred to in the industry as “spillover” — and can be caught once again.

On the personal level, choosing sustainably caught fish creates an impact. The U.S. is a top importer of seafood (Americans consumed around 6.3 billion pounds of seafood in 2019, 90% of which was imported), so our choices can have a large influence on global practices around fisheries. Here’s how to choose sustainable fish for yourself and your household:

Huge demand for fish and inadequate management of fisheries has allowed overfishing to continue. If unchecked, this decline in fish populations will have devastating impacts on the environment, food security, and the many economies that depend on the fishing industry. However, the many legislative and technological solutions to overfishing are in our hands.

The post Overfishing 101: Everything You Need to Know appeared first on EcoWatch.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has released new data that shows the drinking water consumed by 26 million Americans across the country is contaminated with dangerous levels of toxic per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) “forever chemicals.”

PFAS are a group of almost 15,000 synthetic chemicals that have become ubiquitous in the environment after having been used in the making of water-repellent clothing, nonstick cookware, stain resistant fabrics, consumer products like cosmetics and in other capacities for years. PFAS are known as “forever chemicals” because they are resistant to water, oil, heat and grease, and do not break down naturally in the environment.

Toxic forever chemicals have been linked to health problems like cancer, thyroid disease, liver damage, fertility issues and obesity.

The EPA’s Fifth Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule, or UCMR5, requires U.S. water utilities to test their drinking water for 29 distinct PFAS compounds, a press release from the Environmental Working Group (EWG) said.

“For decades, millions of Americans have unknowingly consumed water tainted with PFAS,” said Scott Faber, senior vice president for government affairs at EWG, in the press release.

Initial data released by the EPA said PFAS levels found in 431 water systems were above minimum reporting limits.

The toxic PFAS levels were found in all 50 states, in the District of Columbia and in two territories at 2,800 locations, but since just 29 PFAS compounds were tested, the actual scale of PFAS drinking water contamination is predicted to be much bigger.

“The new testing data shows that escaping PFAS is nearly impossible. The EPA has done its job, and the Biden White House must finalize drinking water standards this year,” Faber said in the press release.

An interactive map by EWG shows which private and public water systems across the U.S. are known to be contaminated with PFAS and will be updated with the new information from the EPA.

Additional UCMR5 PFAS testing will happen between this year and 2025, with quarterly data expected.

The results of the EPA tests revealed that cities like Denver, Los Angeles and Austin had PFAS in their tap water, as well as smaller communities in places like New Jersey and Illinois. The testing also showed PFAS drinking water contamination in areas where it had not been detected before. Some water samples even contained high levels of PFOS and PFOA — the most notoriously bad and most studied of the PFAS compounds — that surpassed proposed EPA limits.

“The initial data indicate that multiple forever chemicals are being detected in public water systems, with two specific PFAS (PFOS and PFOA) concentrations above the proposed maximum contaminant levels (the highest levels of a contaminant that is allowed in drinking water) in over 150 systems,” said Elizabeth Southerland, a former EPA water specialist now with the advocacy group Environmental Protection Network, as Common Dreams reported. “It is critically important that EPA continue to release this data every quarter so the public can see as quickly as possible if their drinking water has PFAS levels of concern.”

The EPA has promised to make their drinking water standards final by the end of this year, the press release said. However, it is likely that drinking water utilities will be given from three to five years for compliance. Ten states currently have PFAS drinking water limits.

“The PFAS pollution crisis threatens all of us,” said Melanie Benesh, EWG’s vice president of government affairs, in the press release. “The EPA’s proposed limits also serve as a stark reminder of just how toxic these chemicals are to human health at very low levels. The agency needs to finalize its proposal and make the limits for PFAS in water enforceable.”

According to EWG estimates, almost 30,000 industrial polluters could be releasing PFAS into the environment.

“Communities and families across the nation are bearing the burden of chemical companies’ callous disregard for human health and the government’s inaction. This PFAS crisis calls for immediate action to ensure all Americans have safe and clean drinking water. That means ending all non-essential uses of PFAS, such as those compounds used in the everyday products we bring into our homes,” Faber said in the press release.

EWG recommends using a reverse osmosis filtration system at your tap or under your sink and replacing the filter routinely as instructed if you think there might be PFAS in your water.

The post Drinking Water for 26 Million Americans Contaminated With Dangerous Levels of PFAS ‘Forever Chemicals,’ New EPA Data Says appeared first on EcoWatch.

The University of Pittsburgh and and the Pennsylvania Department of Health have released the results of a project that studied three health concerns and natural gas development. Of the results, the studies found that children living within 1 mile of at least one natural gas well were five to seven times more likely to develop lymphoma, compared to children living 5 miles away from a well.

The project kicked off in 2020, when the Pennsylvania Department of Health reached out to the University of Pittsburgh School of Public Health to conduct studies on childhood cancer, asthma and birth outcomes in relation to unconventional natural gas development, including fracking, which increased significantly in Southwestern Pennsylvania through the 2000s.

People in the area were concerned about childhood cancer, including Ewing sarcoma, according to the project report. This led the community to reach out for a study on childhood cancer and fracking.

The researchers reviewed health data from 1990 to 2020 and conducted studies from 2021 to 2023. While the project didn’t find a link between living near wells and leukemia, brain tumors or bone cancers (including Ewing sarcoma), the researchers did find that living within one mile of one or more wells increased the risk of children developing lymphoma by five to seven times.

Development of lymphoma is rare, with about a 0.0012% average rate of incidence in people under 20 years old in the U.S. But the study researchers estimated that for those living near wells, the rate would be about 0.006% to 0.0084%.

James Fabisiak, a co-investigator on the project, told Grist that the results don’t necessarily mean that there isn’t a connection to the other types of childhood cancer, though.

“In any scientific study like this, you always have some uncertainty about the negative result,” Fabisiak told Grist. “If I had more patients, if I had more sample size, might I find a statistically significant difference?”

In a 2022 study by the Yale School of Public Health, results showed that children living near unconventional oil and gas development sites in Pennsylvania at birth had a two to three times higher chance of receiving a leukemia diagnosis from ages 2 to 7.

In addition to the research on childhood cancer, the project also studied impacts on asthma and birth outcomes. For people with asthma, living near unconventional natural gas development in its production phase increased the chance of an asthma attack by four to five times, according to the report.

Further, living near unconventional natural gas development was also linked to a minor impact on birth weight, leading to about a 20 to 40 grams, or about 1 ounce, reduction.

The researchers pointed out that these studies do not show a causation of diseases, but rather an association, nor did they determine which specific hazardous agent could be linked to the health outcomes. But the studies do provide more information and add to growing research on fossil fuels and health impacts.

The post Children Living Near Fracking Sites More Likely to Develop Lymphoma, Pennsylvania Studies Find appeared first on EcoWatch.

Considered by many to be the father of wildlife ecology, Aldo Leopold was a scientist,…

The post Earth911 Inspiration: Harmony Between Men and Land appeared first on Earth911.