This coverage is made possible through a partnership between WBEZ and Grist, a nonprofit environmental media organization. Sign up for WBEZ newsletters to get local news you can trust.

Earlier this month, Paulina Vaca stood at the corner of Pulaski Road and 41st Street, one of Chicago’s busiest intersections for truck traffic.

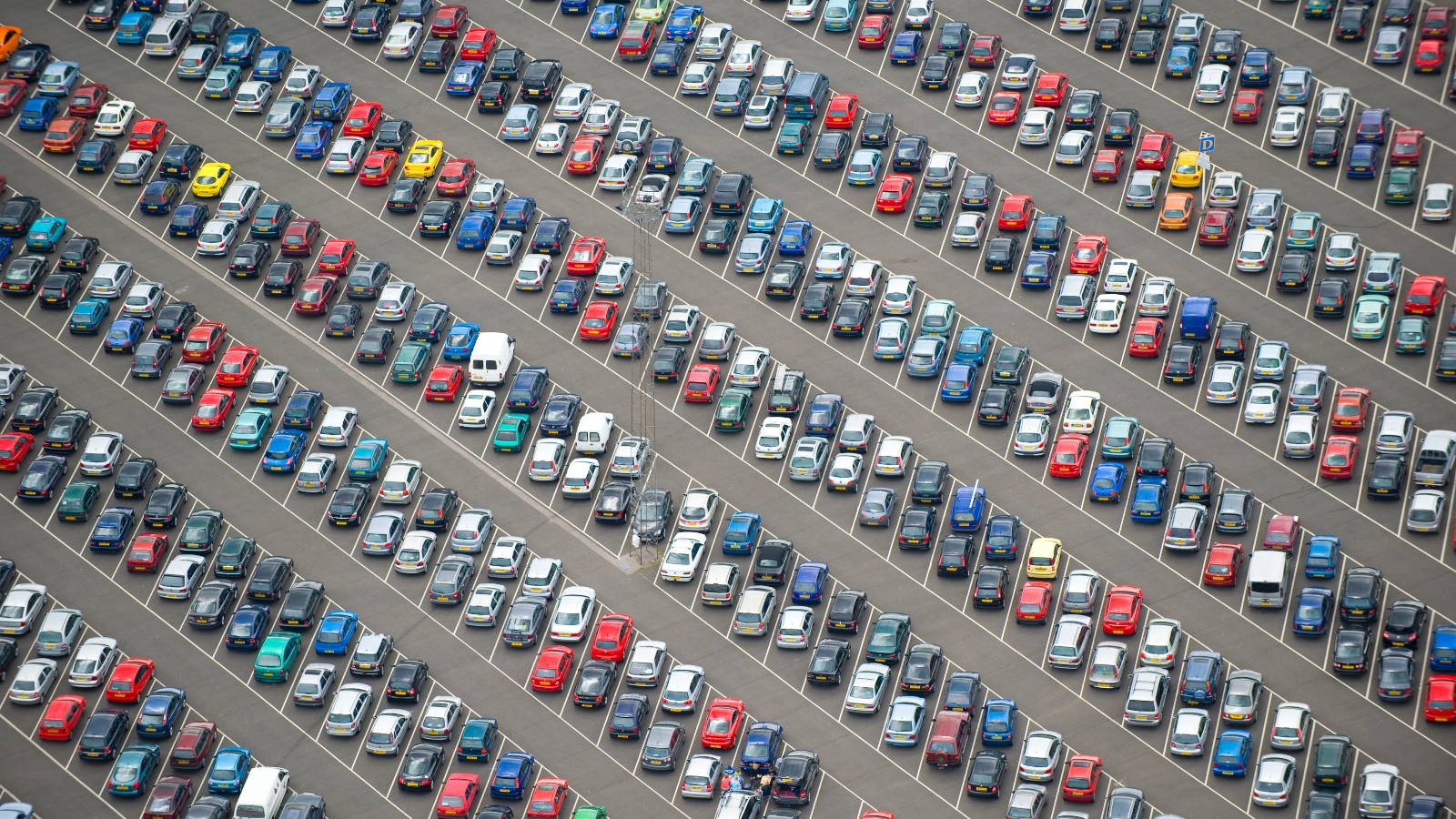

“I’m seeing a sea of trucks,” said Vaca, who works with the Center for Neighborhood Technology, or CNT. In less than 60 seconds, she counted eight trucks.

That was just the beginning. In less than one hour, about 430 trucks passed through the intersection she was monitoring in Archer Heights, a mostly Latino community on the Southwest Side of the city. She was joined by José Miguel Acosta Córdova, who works for a community group known as the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization.

The two organizations recently put out a report measuring the extent of the city’s truck traffic, counting trucks moving through one nearby suburb and 17 Chicago neighborhoods. Using sensors installed in 35 spots, they tracked the number of medium- and heavy-duty trucks that went past in a span of more than 24 hours. Over the course of a day, more than 5,100 trucks and buses were recorded in Archer Heights — the most of any neighborhood.

That data points to key questions that Chicago and Illinois need to answer, said Acosta Córdova.

“When are there too many warehouses and when are there too many trucks?” he asked.

That’s a question that goes beyond Chicago, which happens to be the largest freight hub in North America. Black and brown communities living near the industrial corridors of many urban areas are disproportionately paying for it with their health.

Vaca and Acota Córdova are not alone in their research on local traffic. Across the country, local groups are increasingly finding ways to quantify the extent of localized air pollution, transforming real-time data into useful information that neighbors can use to inform day-to-day decisions, like whether or not to stay inside.

While state and federal agencies do actively monitor air quality, their networks are limited, according to a United States Government Accountability Office report published last month. The national ambient air quality monitoring system is not designed to pinpoint pollution hotspots. More and more, localized data is exactly what frontline communities are calling for in order to protect and advocate for themselves.

“They want to know better than what their pollution level probably is,” said James Bradbury, the director of research and policy analysis at the Georgetown Climate Center, a nonpartisan research institution that studies federal and state climate policies.

“They would like to have more granular and specific information that informs what’s happening in their communities,” Bradbury said.

Community air quality monitoring programs are taking off across the country, he added.

From Newark, New Jersey, to the Bay Area, local organizations are counting trucks and installing small networks of air quality sensors to fill the gap left open by state monitoring systems. As of 2022, the federal government had funded over 130 community air monitoring projects nationwide to the tune of $53.4 million.

Freight continues to be a major economic juggernaut in the Chicago region, and it comes at a significant health cost. The Respiratory Health Association ranked Illinois fifth out of all states for the highest number of deaths from diesel engine pollution per capita in 2023.

Diesel is what, in large part, moves freight around, according Brian Urbaszewski, director of environmental health programs for the Respiratory Health Organization.

“What comes out of the tailpipe of those engines is a collection of air pollutants: everything from nitrogen oxides to fine particulate matter, and even carbon dioxide,” Urbaszewski said. Exposure to these pollutants are associated with a host of medical issues, ranging from respiratory to cardiovascular health impacts.

Acosta Córdova said Illinois needs to adopt tighter truck regulations that are already in use in California and several other states. These policies would raise emission standards for tailpipe pollution and set a path for zero-emission trucks.

Vaca said that this new trucking data she and her colleagues compiled won’t surprise longtime residents of the city’s industrial corridors. But it is hard evidence that she hopes will help convince elected leaders that air pollution is an issue of life or death.

“Having these numbers, it’s really crucial to then advocate for more electric vehicles,” Vaca said. “To use this to advocate against permitting more industry in areas where it’s already overburdened.”

More than 1,000 lives and over $10 billion could be saved annually if the Chicago region electrified approximately 30 percent of all light and heavy-duty vehicles, according to a study published last fall by researchers at Northwestern University.

“We found that the majority of the health benefits from those reductions in pollution occur in environmental justice communities or communities of color, or disadvantaged communities in Chicago,” said Daniel E. Horton, a professor of earth and planetary sciences at Northwestern.

Earlier this month, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency announced finalized federal emissions standards for heavy vehicles that would require manufacturers to limit pollution from heavy trucks beginning in 2030. It’s estimated the new policy will prevent a billion tons of greenhouse gas emissions from entering the atmosphere. But Acosta Córdova said the guidelines do not go far enough to address the climate crisis. In Illinois, it’ll be years before residents see relief from freight driven air pollution.

“The biggest thing we want to see out of this is more data collection,” Acosta Córdova said. “But, also eventually, [we want] a full transition to zero emission trucks.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Monitoring a ‘sea of trucks’ in Chicago on Apr 16, 2024.

An Ocean of Potential (@ourocean2024)

An Ocean of Potential (@ourocean2024)