When Chelsea Wood was a child, she would often collect Periwinkle snails on the shores of Long Island.

“I used to pluck them off the rocks and put them in buckets and keep them as pets and then re-release them,” Wood said. “And I knew that species really well.”

It wasn’t until years later that Wood learned that those snails were teeming with parasites.

“In some populations, 100 percent of them are infected, and 50 percent of their biomass is parasite,” Wood said. “So the snails that I had in my bucket as a child were not really snails. They were basically trematode [parasites] that had commandeered snail bodies for their own ends. And that blew my mind.”

Wood, now a parasite ecologist at the University of Washington, sometimes refers to parasites as “puppet masters,” and in many cases, it’s not an exaggeration. Some can mind-control their hosts, for example, causing mice to seek out the smell of cat pee. Others can shape-shift their hosts, physically changing them to look like food. And their ripple effects can reshape entire landscapes.

For centuries, people have thought of parasites as nature’s villains. They often infect people and livestock. In fact, parasites are by definition bad for their hosts, but today, more scientists are starting to think about parasites as forces for good.

“I don’t think anyone is born a parasitologist. No one grows up wanting to study worms,” Wood said. “Somewhere along the way, I like to say, they got under my skin. I just fell in love with them. I couldn’t believe that I’d gotten that far in my biology education and no one had ever mentioned to me that parasites are incredibly biodiverse, ubiquitous, everywhere.”

On a cloudy August morning, Wood took me to Titlow Beach in Washington state, one of her team’s research sites. Back in the 1960s, one of Wood’s research mentors had sampled shore crabs here. At the time, the area was very industrial and heavily polluted. But when researchers, including Wood, came back to collect samples half a century later, the beach had transformed. The water was cleaner and the shorebirds had returned, but those weren’t the only promising signs: The crabs were now full of trematode worms, a type of parasite that jumps between crabs and birds.

Chelsea Wood kneels to search for shore crabs at a beach in Tacoma, Washington. She will later dissect the crabs to search for parasites. Jesse Nichols / Grist

The parasites were a sign that the local shorebirds were doing great, Wood explained.

As scientists have learned more about parasites, some have argued that many ecosystems might actually need them in order to thrive. “Parasites are a bellwether,” she said. “So if the parasites are there, you know that the rest of the hosts are there as well. And in that way they signal about the health of the ecosystem.”

To understand this counterintuitive idea, it’s helpful to look at another class of animals that people used to hate: predators.

For years, many communities used to treat predators as a kind of vermin. Hunters were encouraged to kill wolves, bears, coyotes, and cougars in order to protect themselves and their property. But eventually, people started noticing some major consequences. And nowhere was this phenomenon more apparent than in Yellowstone National Park.

In the 1920s, gray wolves were systematically eradicated from Yellowstone. But once the wolf population had been eliminated from the park, the number of elk began to grow unchecked. Eventually, herds were overgrazing near streams and rivers, driving away animals including native beavers. Without beavers to build dams, ponds disappeared and the water table dropped. Before long, the entire landscape had changed.

In the 1990s, Yellowstone changed its policy and reintroduced gray wolves into the park. “When those wolves came back in, it was like a wave of green rolled over Yellowstone,” Wood said. This story became one of the defining parables in ecology: Predators weren’t just killers. They were actually holding entire ecosystems together.

“I think there’s a lot of parallels between predator ecology and parasite ecology,” Wood said.

Like the gray wolves in Yellowstone, scientists are just starting to recognize the profound ways that ecosystems are shaped by parasites.

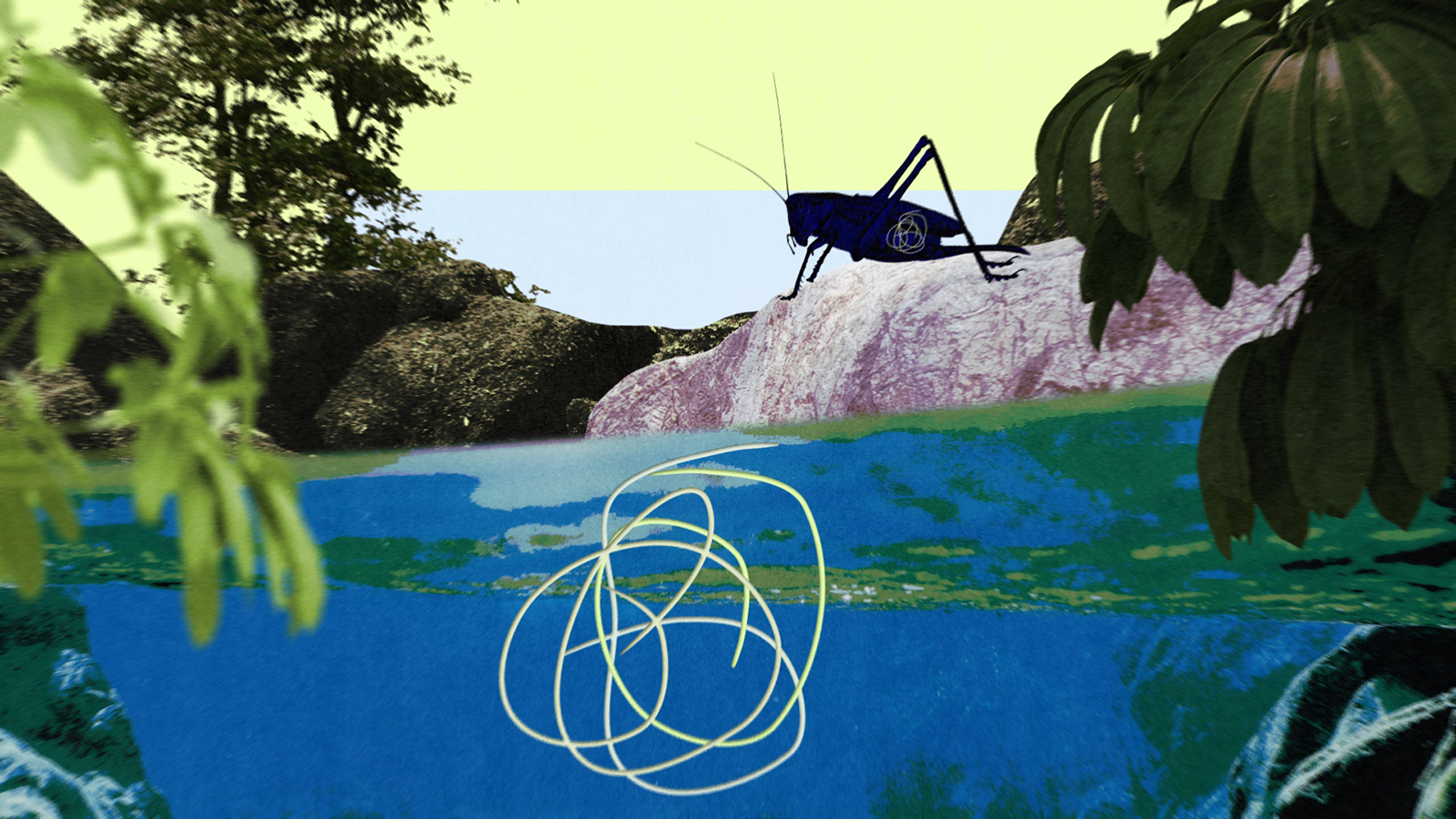

Take, for example, the relationship between nematomorphs, a type of parasitic worm, and creek water quality. The worms are born in the water, but spend their lives on land inside of bugs, like crickets or spiders.

At the end of their lives, nematomorphs need to move back to the water to mate. Instead of making the dangerous journey themselves, they trick their infected hosts into giving them a ride by inducing a “water drive,” an impulse on the part of its insect host to immerse itself in water. The insect will move to the edge of the water, consider it for a little while and then jump in — to its own death, but to this parasite’s benefit.

The story doesn’t end there. In a way, the entire creek ecosystem relies on a worm trying to hitch a ride to the water. Fish eat the bugs that throw themselves in the water. In fact, one species of endangered trout gets 60 percent of its diet exclusively from these infected bugs. “So essentially, the parasite is feeding this endangered trout population,” Wood said.

With less of the threat associated with hungry fish, the native insects in the stream can thrive, eating more algae and thereby giving the creek clear water.

Parasites make up an estimated 40 percent of the animal kingdom. Yet, scientists know next to nothing about millions of parasite species around the world. The main parasites that scientists have spent a lot of time studying are the ones that infect farm animals, pets, and people.

Many of these alarming parasites, like ticks or the parasitic fungus that causes Valley Fever, are expected to increase due to climate change. But no one actually knows what climate change means for parasites, broadly — or how any big change in parasites might reshape the world. “There’s this general sense that infection is on the rise, that parasites and other infectious organisms are more common than they used to be,” Wood said. “At least for wildlife parasites, there really isn’t long-term data to tell us whether that impression that we have is real,” Wood said. “We had to invent a way to get those data,” Wood said.

Wood had an unconventional idea of where to look: a collection of preserved fishes locked away in a museum basement.

Jesse Nichols / Grist

The University of Washington Fish Collections is home to more than 12 million samples of preserved fishes, dating all the way back to the 1800s. But the thousands of jars lining the collection shelves also contain something else: all the parasites living inside the fish samples.

“So much has been discovered from museum specimens that we tucked away at one time, and then pulled off the shelf 100 years later,” said Wood. “It’s really remarkable to get to peer back in time the way that you do when you open up a fish from a hundred years ago. It’s the only way that we’ll know anything about what the oceans were like, parasitologically, that long ago.”

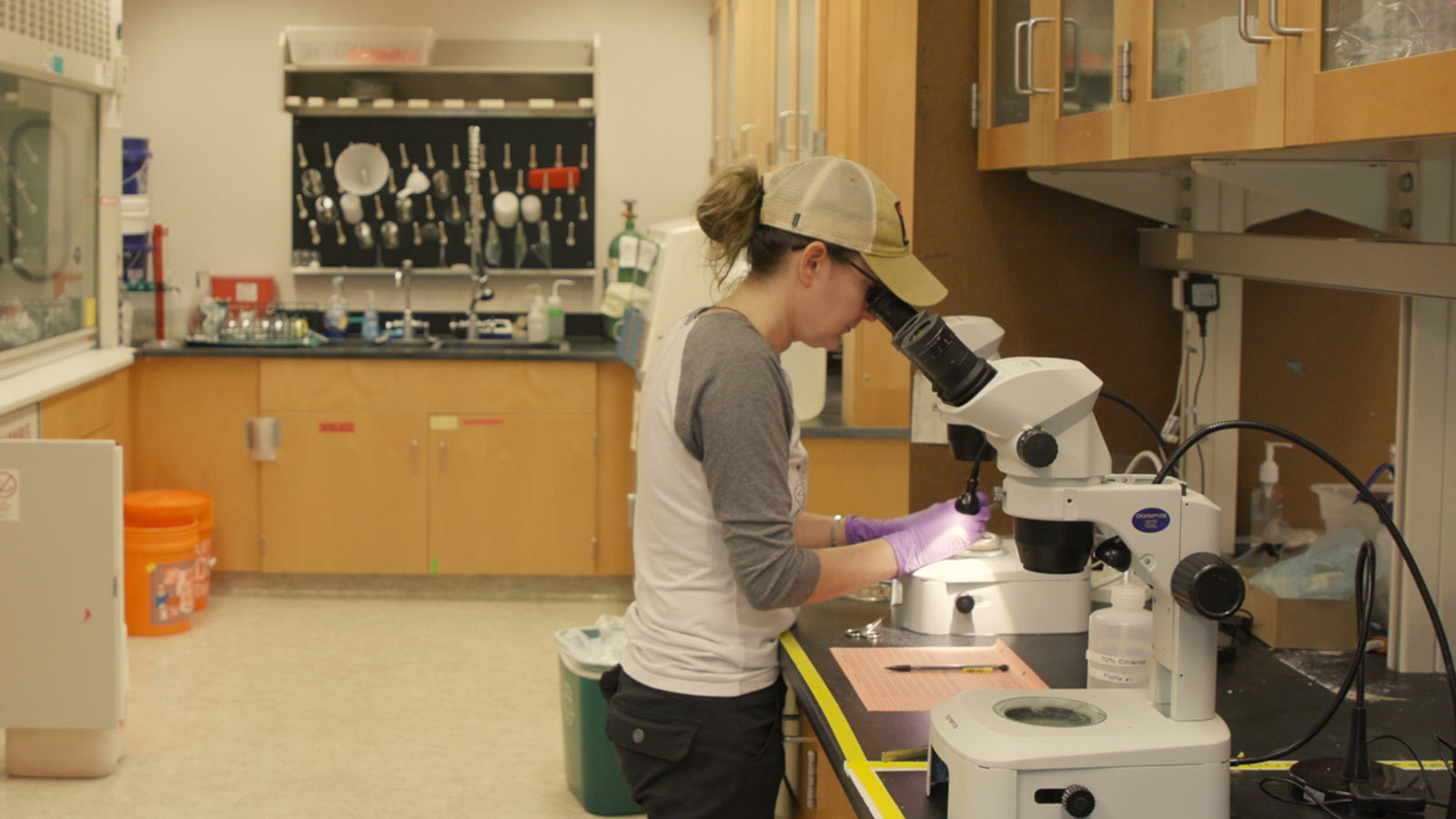

Chelsea Wood dissects fish samples in her lab at the University of Washington. Jesse Nichols / Grist

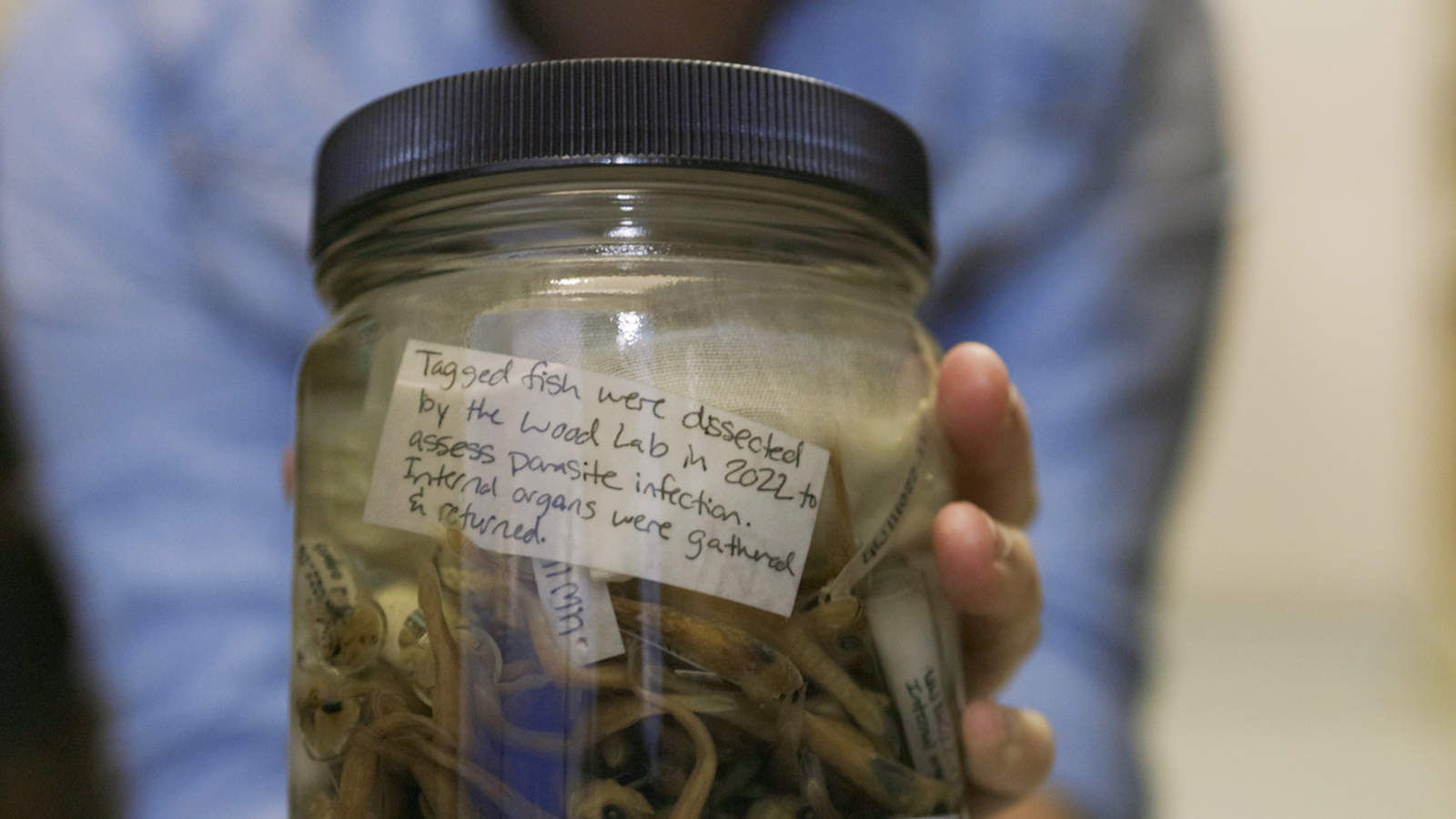

Wood and her team spent over two years opening up jars and surgically dissecting the parasites from within. Under microscopes, they identified and counted the parasites before returning everything for future study. In the end, they found more than 17,000 parasites.

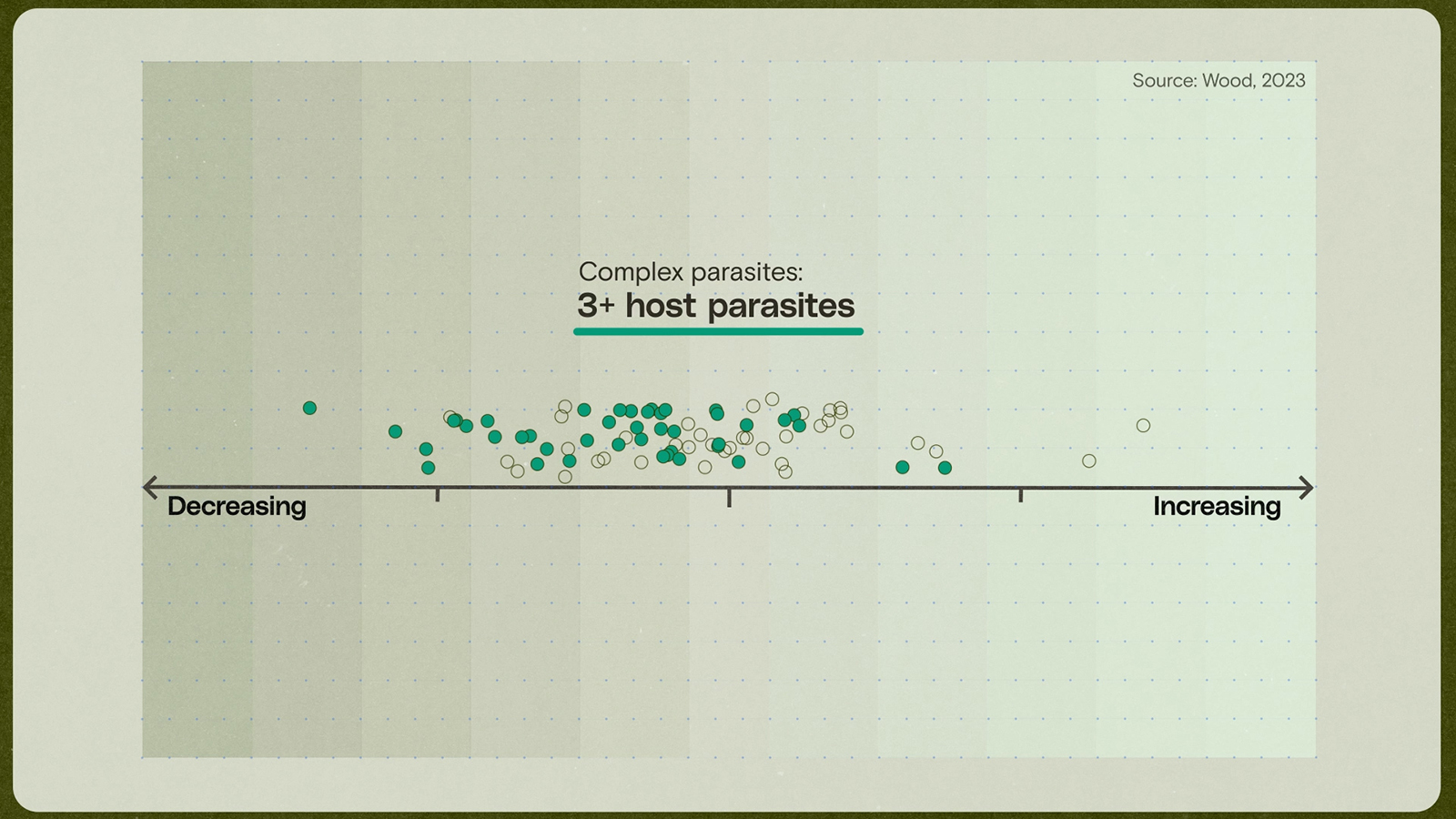

Looking at the number of parasites found in fishes over time, the researchers found a mix of winners and losers, but there was one big class of parasites that was unequivocally declining: complex parasites, the kinds that need several different host species in order to survive. That type of parasite declined an average of 10 percent each decade, the team found.

In Wood’s investigation, there was only one factor that perfectly explained the decline in parasites: It wasn’t chemicals or overfishing. It was climate change. It made a lot of sense: Complex parasites can only survive if everyone one of those host species are around. If just one type of host goes missing? “Game over. That’s it for that parasite,” Wood said. “That’s why we think that these complex life cycle parasites are so vulnerable: because things are shifting, and the more points of failure you have, the likelier you are to fail.”

Wood said that, before this study, researchers had no idea climate change was wiping out this important class of parasites.

Jesse Nichols / Grist

“It’s likely a collateral impact,” she said. “We don’t even have a handle on how many parasites there are in the world, much less the scale of parasite biodiversity loss right now. But the early indications are that parasites are at least as vulnerable as their hosts, and potentially more vulnerable.”

Wood says that it’s important for people to understand that parasites play huge and complex roles in nature, and if we ignore what we can’t see, we risk missing out on understanding how the world really works. “We all have a reflexive distaste for parasites, right? We take drugs, we apply chemicals, we spray, Wood said. “Our argument is that parasites are just species. They’re part of biodiversity, and they’re doing really important things in ecosystems that we depend upon them for.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Nature can’t run without parasites. What happens when they start to disappear? on May 7, 2024.