The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) recently launched the $5.1 million Wind Turbine Materials Recycling Prize….

The post Wind Turbine Recycling Prize Offers $5.1 Million to Entrepreneurs, Promotes Local Solutions appeared first on Earth911.

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) recently launched the $5.1 million Wind Turbine Materials Recycling Prize….

The post Wind Turbine Recycling Prize Offers $5.1 Million to Entrepreneurs, Promotes Local Solutions appeared first on Earth911.

Today’s inspiration is from Bob Brown, an Australian environmentalist, doctor, former politician, and founder of…

The post Earth911 Inspiration: A Green Future or None at All appeared first on Earth911.

Modern clothing is a technological marvel — it’s brighter than ever, more flame-resistant, more water-repellent.

It’s also often toxic. The properties we’ve come to know and expect stem from fossil fuel-derived chemicals that, according to a growing body of research, are making people sick.

There are the brominated azobenzene disperse dyes, which give polyester clothes their bright colors but can cause skin inflammation. There are the per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, also known as PFAS or “forever chemicals,” which make clothes waterproof but are linked to thyroid disorders and cancer. There are carcinogens like formaldehyde, used for bleaching or to prevent mold, and hormone disruptors like NPEO, used as a cleaning agent.

And then there are the hundreds, if not thousands, of chemicals that we know vanishingly little about. Paltry funding and patchy oversight from the Environmental Protection Agency and the Consumer Product Safety Commission, an independent federal agency, mean the U.S. government isn’t checking most of the clothes we buy for toxicity. When problems do arise for people — when they suspect that their clothing is behind their pesky rash, their wheezing cough, their splotchy skin — they are often disbelieved and offered little to no recourse from manufacturers, whether in the form of reimbursed medical bills or monetary damages.

This all-too-familiar story played out in a big way during the 2010s, when flight attendants at four major airlines began reporting severe reactions to new uniforms made from synthetic fabrics. Headaches, dizziness, loss of memory — even being near other flight attendants who had the clothes on seemed to cause symptoms, in a few cases. For some employees, the reactions were so bad they had to be hospitalized. Others began limiting their time on the plane, and some eventually quit — or were fired for taking too many unexcused absences.

Usually, it’s hard to pin symptoms precisely on clothing, but the flight attendants had all begun wearing the uniforms at the same time and were consistently keeping them on for long periods in a small, enclosed space. This suggested that it was the uniforms, and not another factor, that was causing their symptoms. Public health researchers at Harvard University later analyzed contemporaneous survey data and found a significant increase in the prevalence of rashes, itchy eyes, sore throats, shortness of breath, and other health complaints after Alaska Airlines introduced its new uniforms. (Three of the airlines, including Alaska, eventually ordered new uniforms, but without admitting the old ones had caused health problems.)

Alden Wicker, a sustainable fashion writer, documents the story in To Dye For, her new book on the fashion industry’s toxic underbelly. Hazardous substances have been used in clothes for centuries, she told Grist, but with the advent of fossil fuel-based chemistry, the dangers have multiplied, growing alongside the number of unpronounceable chemicals available to today’s clothiers. Many of these chemicals act in concert with each other: toxic on their own, but potentially even worse when mixed together on the same piece of fabric. Scientists know alarmingly little about how these chemical combinations affect human health.

“We’re just immersed in this miasma of chemicals that researchers know are toxic, and nobody’s protecting us,” Wicker said. Out of the up to 60,000 chemical substances and polymers currently registered for use in various industries, the U.S. only bans three from textiles, and that’s only for children’s products.

Grounded in the firsthand experiences of those flight attendants — some of whom are still fighting for their symptoms to be recognized by their airlines, doctors, and insurance companies — To Dye For reveals how the fashion industry got here and what needs to change to keep people safe.

This Q&A has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.

Q.People tend to think that exposure to toxic substances and chemical pollution in the textile industry primarily happens “over there” in developing countries. But chemicals don’t stay put. How is this a global problem?

A.A lot of the chemicals that people hear about being used in garment factories, not all of them are effectively washed off during the process of creating, dyeing, and finishing fashion. Some can be left behind as residues. More importantly, some are deliberately applied and are meant to stay on for a long period of time — like dyes for things like polyester. Recent research out of Duke has shown that those dyes are ending up in our house dust from the polyester textiles we bring into our homes. And we’re breathing them in or touching them or ingesting them.

Q.There have been toxic ingredients in clothing for a long time, but things seem to have gotten particularly bad over the past century or so. What happened?

A.Fashion has been toxic for hundreds of years. Before the advent of fossil fuel chemicals, it was mostly heavy metals, the sorts of things that would make you sick with undefinable symptoms over a period of years — things like mercury or arsenic, where they build up in the body and it can be hard to identify what’s happening. With fossil fuels, though, we’ve been able to create — and are still creating — thousands and thousands of chemicals.

Now there can be at least 50 individual chemicals on a textile, if not more than that. So if you imagine a textile, you have 50, 100, 1,000 chemicals all layered on it. And then you’re also wearing multiple pieces of clothing, and there’s a lining, and there’s buttons. How are the chemicals mixing on the textile, and how are they working together when they get into the body? These are things we don’t have answers for.

Q.What is the U.S. doing to protect us from these chemicals?

A.Nobody is protecting us.

While the European Union has banned over 30 chemicals specifically for use in textiles, the U.S. has only banned three, and only in children’s products. And the Consumer Product Safety Commission is severely underfunded. As long as it’s from a legitimate company and it’s not a counterfeit, nobody is checking to make sure that these products are free from known hazardous substances. Consumers are just being hung out to dry.

Q.At least there are some industry-led efforts to keep toxics out of clothes, right?

A.I have a lot of respect for ZDHC [Zero Discharge of Hazardous Chemicals], the industry group that has come up with a “manufacturing restricted substance list.” The problem is that it’s voluntary. There’s a bunch of big brands in there, but if you look at them in terms of their market share, they’re not covering much. We can’t rely on brands to take care, to do their research, to require testing, to invest in good partnerships with their manufacturers. We have to make this the baseline for the industry or else this is going to keep happening.

Q.On a systemic level, what needs to change to keep people safe?

A.We are long overdue for an overhaul in this country of the way chemicals are evaluated and regulated. I think the first step is transparency — getting ingredient lists. If people actually saw the long list of deliberately applied dyes and finishes, I think people would be really, really shocked. And then watchdogs and journalists can leverage that information to push for more legislation.

We should also definitely be regulating chemicals by class. There are at least 12,000 different types of PFAS, and we are not going to be able to evaluate every single one for its toxicity. If a chemical is known to be extremely hazardous, we should just ban or regulate or restrict everything in that same class. Same thing for phthalates. Also, we need more funding for research.

Q.On a personal level, how do we protect ourselves from these chemicals?

A.The first thing I would tell people is to always avoid ultra-fast-fashion brands. If you’ve never heard of the brand, if it’s too cheap to be true, if it has a gibberish name, it’s very risky to shop that brand. I would also say look for labels such as Oeko-Tex, Bluesign, or GOTS [Global Organic Textile Standard], which are not perfect, but they indicate that the brand has had things tested. And always wash your clothes before you wear them, with fragrance-free laundry detergent.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Clothed in chemicals: A new book sheds light on the toxic substances we wear daily on Jul 28, 2023.

July is expected to be the hottest month experienced on earth in 120,000 years – a temperature not felt by human civilization since the end of the ice age.

In a joint report published Thursday by the World Meteorological Organization, the Copernicus Climate Change Service, and Leipzig University, the temperature for the first three weeks of July averaged 62.51 Fahrenheit, breaking the previous record of 61.93 Fahrenheit set in 2019.

In parts of the United States, temperatures have risen above 120 degrees Fahrenheit. In Arizona, people have experienced life-threatening burns from falls on hot pavement, in California, inmates swelter as cooling systems fail, and in the Florida Keys, ocean temperatures rose above 100 Fahrenheit this week, the average temperature of a hot tub.

In Asia, which is responsible for 19 percent of the world’s food and agricultural exports, prolonged heat waves are claiming lives and threatening food security as two major crops – rice and wheat – are at risk of failing.

The report adds that the heat in July has already been so extreme that it’s caused fires around the world including in Italy, Greece and Spain killing 40 people and spreading through 13 countries, while in Canada, the worst fire season in 34 years has led to the destruction of nearly 39-thousand square miles.

An analysis published Monday by the World Weather Attribution group, an international science and research team, found that recent heat waves in North America and Europe were nearly impossible without climate change. Researchers also found that this month’s heat wave in China was 50 times more likely to occur in our current warmer world. All three heat waves were hotter than they would have been without the boost from global warming.

The World Meteorological Organization predicts a 98 percent chance that one of the next five years will be 1.5 Celsius hotter than average in the 19th century—1.5 Celsius is the agreed upon temperature rise limit that world leaders promised to avoid by the end of the century in the Paris Climate Agreement.

“Short of a mini-Ice age over the next days,” said U.N.Secretary-general António Guterres. “July 2023 will shatter records.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline July has been the hottest month in humanity’s history on Jul 28, 2023.

Seagrass meadows are found all over the planet, from the Arctic circle to the tropics, and are vitally important as habitats for fish and for absorbing atmospheric carbon dioxide.

Seagrasses are becoming increasingly threatened by nutrient pollution and overfishing. Every half an hour a football field-sized area of seagrass is lost, reported the UK’s Natural History Museum.

However, a new Caribbean-based study has found that artificial reefs could help seagrass meadows’ plight by heightening their growth and productivity.

“By attracting fish, whose faeces provide concentrated nutrients for the seagrass, the artificial reefs increase the primary production of the entire ecosystem,” said Dr. Jacob Allgeier, an associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Michigan and co-author of the paper, as the Natural History Museum reported. “We are now investigating how this cascades up the food web. The new energy has to go somewhere, so we are quantifying how it affects invertebrates and fish with our evidence suggesting that it is fueling increases in both.”

The study, “Seagrass production around artificial reefs is resistant to human stressors,” was published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

According to a 2020 study, there are approximately 60 species of seagrass. Seagrasses are found in the coastal regions of more than 80 percent of countries, reported the Natural History Museum.

The total area of seagrasses on Earth covers around 115,831 miles, which is about 0.1 percent of the floor of the ocean and approximately the size of the Great Barrier Reef. Seagrass meadows are home to thousands of species of fish and even more invertebrates, providing them with shelter and food.

Seagrasses have the ability to extract nutrients from water and sediment, allowing them to survive in environments that lack an abundance of nutrients. They are also great carbon sinks.

Unfortunately, seagrass meadows have been shrinking for nearly a century. A United Nations report estimates that they are disappearing at a rate of approximately seven percent annually. This causes not only loss of habitat, but the release of vital carbon stores.

The new study showed that the productivity of both undisturbed and disturbed seagrass meadows was improved by the installation of an artificial reef, even in areas with high nutrient pollution.

“Artificial reefs built in seagrass create a positive feedback loop. They attract fish that use the reefs for shelter which, in turn, supply new nutrients from their faeces that fertilise the seagrass around the reef,” said Mona Andskog, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Michigan, who led the research, according to the Natural History Museum. “This increased primary production can increase invertebrate production by providing more food and shelter for invertebrates, which in turn provide more food for fishes.”

Some of the most frequently fished sites in the study were in Haiti, where artificial reefs were shown to provide added benefits to the fish. Large numbers of smaller fish were found, since using nets was difficult around the reef. This meant that the total fish biomass was more than in other areas measured during the study that had not been fished at all.

Artificial reefs could be beneficial for tropical seagrasses, but are likely to have less of an impact on temperate seagrass meadows, since those tend to be more nutrient-rich.

The research team hopes to look into the impact of artificial reefs on seagrass ecosystems, and bring their investigation to the Dominican Republic.

“We will be testing how different configurations of artificial reef clusters can affect the production and fish community composition,” Allgeier said, as the Natural History Museum reported. “This includes the number of artificial reefs in each cluster, as well as their arrangement. As with this research, we hope to simultaneously use the reefs to test fundamental questions about production in these highly impacted ecosystems as well as optimising the positive feedback that is initiated by the artificial reefs.”

The post Artificial Reefs Improve Productivity of Seagrass Meadows and Could Help Protect Against Climate Change, Study Finds appeared first on EcoWatch.

As the climate crisis escalates, there have been a growing number of court cases having to do with climate change. Since 2017, the number of climate cases has more than doubled, according to a new report from the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and Columbia University’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law.

The increasing number of climate change cases indicates that climate-related lawsuits are becoming an essential component of ensuring climate justice.

The Global Climate Litigation Report: 2023 Status Review — based on an evaluation of climate change law, science or policy cases collected through the end of December, 2022, by the Sabin Center’s U.S. and Global Climate Change Litigation Databases — was published today. It is the day before the first anniversary of a declaration by the UN General Assembly that access to a healthy and clean environment is a universal human right, a press release from the UN Environment Programme said.

“Climate policies are far behind what is needed to keep global temperatures below the 1.5°C threshold, with extreme weather events and searing heat already baking our planet,” said Inger Andersen, executive director of UNEP, in the press release. “People are increasingly turning to courts to combat the climate crisis, holding governments and the private sector accountable and making litigation a key mechanism for securing climate action and promoting climate justice.”

As climate litigation continues, the legal precedent accumulates, creating a robust body of law. The UN report gives a summary of important climate litigation over the past two years, including some historic cases.

Some of the major climate litigation cases included the conclusion by the UN Human Rights Committee that a country’s climate inaction and policy violated international human rights law in the case of the Torres Strait Islanders versus the Australian government; the Brazilian Supreme Court finding that the Paris Agreement is a treaty of human rights; and oil and gas corporation Shell being ordered to comply with the Paris Agreement and to reduce its carbon emissions by 45 percent as compared to 2019 levels by 2030, which was the first instance of a duty of a private company being found by a court under the Paris Agreement.

As of 2022, there had been 2,180 climate change cases, more than twice as many as when the number was first assessed in 2017. Most of the cases have been brought in the U.S., but they are happening all over the world, with climate litigation in developing countries, including Small Island Developing States, accounting for about 17 percent of reported cases.

According to the Global trends in climate change litigation: 2023 snapshot from the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), there have been 2,341 climate change cases captured in the Sabin Center’s databases, with 190 of those filed in the past 12 months.

The LSE snapshot said that climate change cases have been identified in Finland, Russia, Romania, Turkey, China, Thailand and Bulgaria.

“More than 50% of climate cases have direct judicial outcomes that can be understood as favourable to climate action. Climate cases continue to have significant indirect impacts on climate change decision-making beyond the courtroom, too,” the LSE report said. “Domestic legal protections (e.g. for the right to a healthy environment) along with domestic climate legislation, play a critical role in cases against governments.”

The UN report said that cases were brought in 65 international, national, regional, quasi-judicial, tribunal and other adjudicatory bodies across the globe.

“There is a distressingly growing gap between the level of greenhouse gas reductions the world needs to achieve in order to meet its temperature targets, and the actions that governments are actually taking to lower emissions. This inevitably will lead more people to resort to the courts,” said Michael Gerrard, Sabin Center’s faculty director, in the press release.

The report shows that vulnerable groups are having their voices heard on climate crisis issues, including 34 cases brought by or on the behalf of youth and children under 25 years old, as well as a case in Switzerland surrounding how climate change disproportionately impacts senior women.

“More cases are being filed against corporate actors, with a more complex range of legal arguments. Around 20 cases filed by U.S. cities and states against the Carbon Majors are now likely to go to trial,” according to the LSE report. “There has been growth in ‘climate-washing’ cases challenging the accuracy of green claims and commitments. Some cases seeking financial damages are also challenging disinformation, with many relying on consumer protection law. Challenges to the climate policy response of governments and companies have grown significantly in number outside the U.S.”

The UN report said most climate change cases fall under one or more of half a dozen categories, including human rights cases; challenges to non-enforcement of laws and policies related to climate domestically; cases regarding keeping fossil fuels sequestered in the ground; greenwashing and the need for greater climate disclosures; corporate responsibility and liability for climate-related harms; and suits that address failures to adapt to climate change impacts.

The report foresees an increasing number of cases brought by Indigenous Peoples and local communities, more climate migration cases and those related to extreme weather liability, as well as more lawsuits brought by groups that are disproportionately affected by the climate crisis.

The report also anticipates roadblocks in the application of climate attribution science and an increase in “backlash” cases aimed at dismantling climate action regulations.

“This report will be an invaluable resource for everyone who wants to achieve the best possible outcome in judicial forums, and to understand what is and is not possible there,” Gerrard said in the press release.

The post Climate Change Lawsuits More Than Double in 5 Years, UN Report Finds appeared first on EcoWatch.

Nearly 100 pilot whales became stranded on Cheynes Beach in Western Australia on Tuesday. Most of the pod, 52 whales, died overnight, and the rest have been euthanized, according to officials, as rescue efforts over two days have failed.

The pilot whales were first seen swimming in the area on Tuesday morning, but they covered much of Cheynes Beach by late afternoon, The Associated Press reported. Volunteers worked to rescue the surviving beached whales on Tuesday and Wednesday.

“What we’re seeing is utterly heartbreaking and distressing,” Reece Whitby, environment minister for Western Australia, said. “It’s just a terrible, terrible tragedy to see these dead pilot whales on the beach.”

Hundreds of volunteers along with Perth Zoo veterinarians and experts in marine fauna worked to move the whales back into the water and were able to do so, but only temporarily, NPR reported. The whales became stranded again on the beach, and the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions announced plans to euthanize the remaining whales.

“DBCA officers and veterinarians have completed assessing the whales that re-stranded on Cheynes Beach this afternoon. Sadly, the decision had to be made to euthanise the remaining whales to avoid prolonging their suffering,” the department announced on Facebook. “It was a difficult decision for all involved however the welfare of the whales had to take precedence. We thank everyone who assisted with the attempt to save the whales over the last two days.”

According to the Whale and Dolphin Conservation, long-finned pilot whales are extremely social animals and are actually part of the dolphin family. Individuals bond closely to others in their pod and will stay together, even if it is dangerous to do so, the organization explained. In the case of the beached pilot whales on Cheynes Beach, wildlife experts predict the pod could have been experiencing stress or illness that caused them to become stranded together.

“The fact that they were in one area very huddled, and doing really interesting behaviors, and looking around at times, suggests that something else is going on that we just don’t know,” wildlife scientist Vanessa Pirotta, a wildlife scientist at Macquarie University, told The Associated Press.

Peter Hartley, a manager for the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, said that experts would be retrieving samples from the pilot whales in hopes of better understanding the pod before the whales are buried.

“We’re going to be learning a lot about the behavior,” Hartley said, as reported by Time. “We’re also going to be learning a great deal about the genetics, the make up of that group, were they related?”

However, the cause of the beaching event is likely to remain unknown, wildlife experts said.

The post Nearly 100 Pilot Whales Die After Beaching in Australia appeared first on EcoWatch.

If you’ve never grown a vegetable garden before, it can be a lot to take…

The post Gardening With the Three Sisters appeared first on Earth911.

The dream that haunts Christine White is always the same, and though it comes less frequently, it isn’t any less terrifying.

The black water comes rushing at the witching hour, barrelling toward her front door in Lost Creek, Kentucky. She’s outside, getting her grandson’s toys out of the yard. It hits her in the neck and knocks her off her feet before racing down a street that has become a vengeful river. She and her husband run to a hillside and scramble upward, grabbing hold of tree roots and branches. She finds her neighbors huddled at the top of the hill. As dawn comes, everything is unrecognizable, the land shifted, houses torn from foundations. They begin to walk through the trees, over the strip mine, out of the forest, in their pajamas and underwear with whatever they were able to carry when they fled.

Then she wakes up.

That night used to replay every time White went to sleep. She started taking antidepressants six months ago, something she felt ashamed of at first but doesn’t anymore. They’ve helped a little, but the dream still haunts her, lightning-seared and vivid.

It’s been one year since catastrophic floods devastated eastern Kentucky, taking White’s home and 9,000 or so others with it. Her current abode — a camper on a cousin’s land — has become, if not home, no longer strange. But it’s the closest thing to home she’ll get till her new house, in another county, is finished. Lost Creek, though, is all but gone forever. What houses remain are empty husks. Some are nothing more than foundations overgrown with grass.

White is never going back. “All the land is gone,” she said.

In the early hours of July 28, 2022, creeks and rivers across 13 counties in eastern Kentucky overran their banks, filled by a month’s worth of rain that fell in a matter of days The water crested 14 feet above flood stage in some places, shattering records. All told, 44 people died and some 22,000 people saw their homes damaged —staggering figures in a region where some counties have fewer than 20,000 residents. Officially, the inundation destroyed nearly 600 homes and severely damaged 6,000 more. A lot of folks say that tally is low, based on the number of residents who sought help from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. As of March about 8,000 applications for housing assistance had been approved. That’s half the number the agency received.

The need for help, specifically housing assistance, was, and remains, acute. Most people here live on less than $30,000 a year, and at the time of the disaster, no more than 5 percent had flood insurance. Multitudes of nonprofits, church and community organizations, businesses, and government agencies have spent months pitching in as best they can. Yet there is a feeling among the survivors that no one’s at the rudder, and it’s everyone for themselves.

President Biden issued a federal disaster declaration the day after the flood, and his administration has disbursed nearly $300 million in aid so far. The state pitched in, too, housing 360 families in trailers parked alongside those from FEMA. Many of those have moved on to more permanent housing, but up to 1,800 are still awaiting a solution.

Some in the floodplains are taking buyouts — selling their homes to the federal government, which will essentially make the land a permanent greenspace. It’s a form of managed retreat, a ceding of the terrain to a changing climate. Some local officials openly worry that the approach doesn’t solve the biggest problem everyone faces: figuring out where on Earth people are going to live now. Eastern Kentucky was grappling with a critical shortage of housing even before the flood, and much of the land available for construction lies in flood-prone river bottoms. That has people looking toward the mountaintops leveled by strip mining.

Kate Clemons, who runs a nonprofit meal service called Roscoe’s Daughter, sees this crisis every day. As the water receded, she started serving hot meals in the town of Hindman a few nights each week, on her own dime. She figured it would be a months’ work. She’s still feeding as many as 700 hungry people every week. Recently, an apartment building in Hazard burned down, displacing nearly 40 people. Some of them were flood survivors. They’ve joined the others she’s taken to helping find homes.

“There’s no housing available for them,” she said.

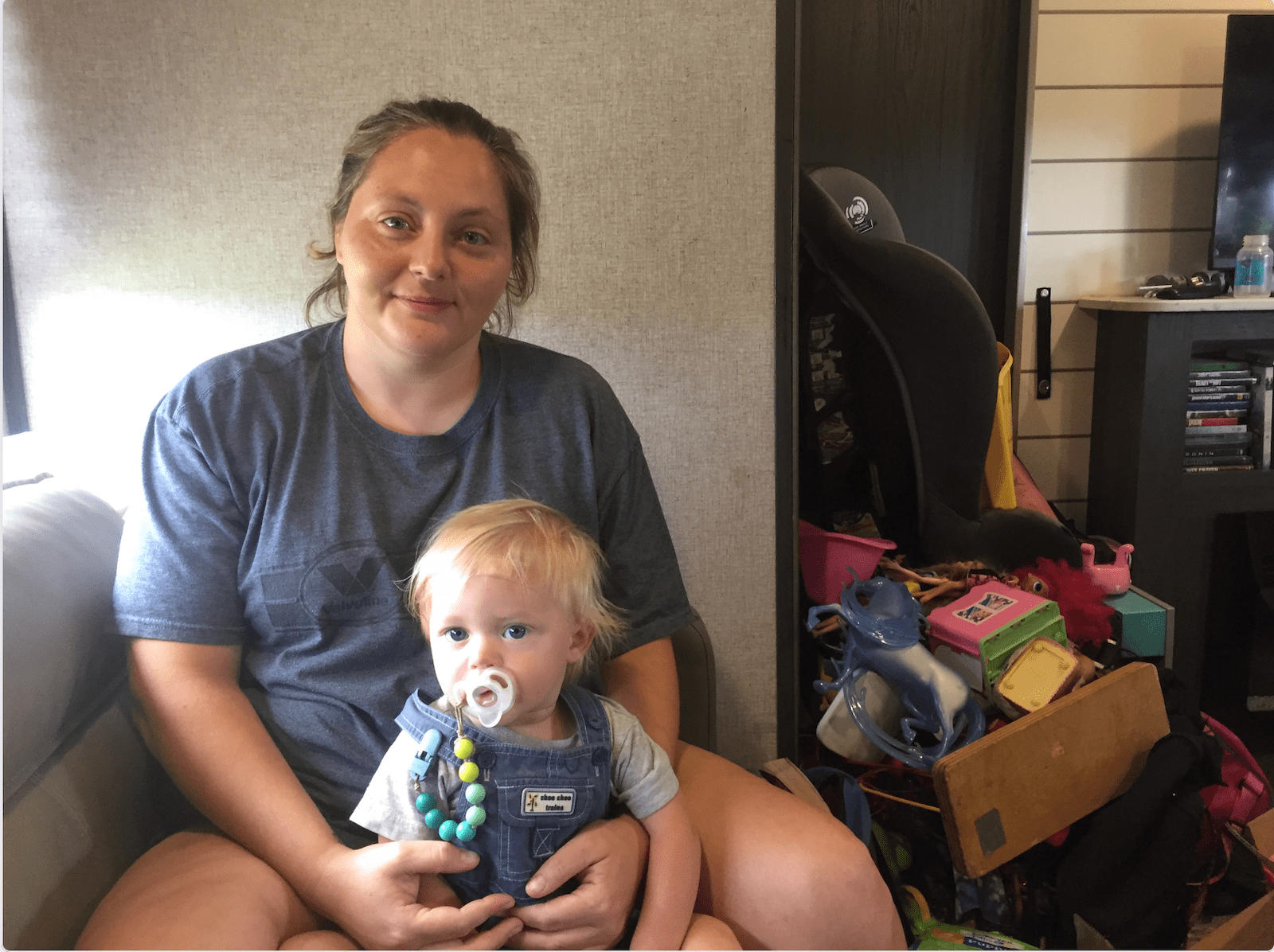

Clemons often brings food to Sasha Gibson, who after the flood moved with her boyfriend and nine children into two campers at Mine Made Adventure Park in Knott County. At first, she felt optimistic. “I was hoping that this would open up a new door to something better,” she said, after asking her children to go to the other trailer so she could sit for the interview in her cramped quarters. “Like this is supposed to be a new chapter in our lives.”

But the park, built on what was once a strip mine, became purgatory instead.

Gibson, who lived on family land before the rains came, wants to leave. It’s just that the way out isn’t apparent yet. Many rentals won’t take so big a family. It doesn’t help that many of their identity documents were lost to the flood, making the search that much harder. She got some help from FEMA, but said the money went too quickly.

A caseworker helps navigate a labyrinth of agencies designed to help Kentucky flood victims, and they’ve put in applications at a grab bag of charities building housing. One has told Gibson her case looks promising, but she’s still waiting to hear a final word. Other applications are so long and such a crapshoot — one ran 40 pages, for a loan she’d struggle to pay back — that she’s too tired to put them together.

“It’s a big what-if game,” she said. “They’re not reaching out to you. You’re expected to call them.”

Meanwhile, ATV riders sometimes ride through to the park, kicking up dust and leaving a mess in the restrooms. Gibson tries not to resent them. It’s not their fault she’s stuck.

“While it’s great and, like, they’re having a good time, it’s not a great time for us because we feel like we’re stuck here and we’re, like, an inconvenience and we’re in the way,” she said. “We don’t want to bother anybody.”

As extreme weather intensifies due to climate change, stories like Gibson’s will play out in more and more communities. Though eastern Kentucky hadn’t flooded like this since 1957, parts of the state could face 100-year floods every 25 years or so. About half of all homes in the region hit hardest by last year’s floods — Knott, Letcher, Perry, and Breathitt counties — are at risk for extreme flooding.

Some residents worry that the legacies of surface mining – lost topsoil and tree cover, a ruined water table, and waste retention dams like the one that may have failed near Lost Creek, drowning it – will make communities more vulnerable to floods, compounding the effects of generational poverty and aging rural infrastructure. Housing needs to be built, and some say it needs to go up on the only high, flat land available — that is, the very same strip mines that contributed mightily to this whole problem in the first place.

High ground, especially former strip mines, in the region tends to be off limits. A study completed in the 1970s showed that most of what is available belongs to land companies, coal companies, and other private interests. About 1.5 million acres is believed to have been mined. Many of those sites are too remote to be of much use for housing, though, and those that are closer to town typically have seen commercial development. As the flood recovery has dragged on, though, some of these entities have decided to donate some of what they hold so that there might be more residential construction. Other parcels have been donated by landowning families with cozy relationships to the coal industry, though that hasn’t always gone smoothly.

Chris Doll is vice president of the Housing Development Alliance, a nonprofit dedicated to building single-family homes for low-income families. It was beating the drum of eastern Kentucky’s crisis long before the flood. The situation is even more dire now. Without an influx of new construction, he argues, the local economy will spiral even further.

On an overcast and gentle day in June, Doll walked around a former strip mine turned planned development in Knott County called Chestnut Ridge. It sits near a four-lane highway and close to other communities, with ready access to water lines. The Alliance is working with other nonprofits to build around 50 houses here, along with, it hopes, 50 to 150 more on each of two similar sites in neighboring counties. A $13 million state flood relief fund has committed $1 million to the projects.

The road leading to what could, in just a few years, be a bustling neighborhood opened up into a bafflingly flat landscape, almost like a wooded savanna. It was wide open to the sunshine, unlike the deep hollers and coves that characterize this part of eastern Kentucky. To an untrained eye, it appeared to be a healthy ecosystem. Look closer, though, and one sees the mix of vegetation coal companies use to restore the land: invasive autumn olive, scrubby pine trees, and tall grasses, planted mostly for erosion control.

Still, it’s ideal land for housing, and most folks around here won’t mind the landscaping. Doll said the number of people who need help is overwhelming, and his team can’t help everybody. But they hope to build as many houses as they can.

“There are so many people that have so many needs that I am of the mindset that I will help the person in front of me,” Doll said. “And now we can turn them into homeowners. If that’s what they want.”

On a hillside overlooking another mine site, Doll and I walked up to the ridge to see if we could get a better view of the terrain. It is covered in a thicket of brush, too dense to see beyond. The path wound toward a small clearing, where worn headstones and stone angels sit undisturbed. Family cemeteries are protected from strip mining, and this one was clearly still cared for; the bouquets at the angels’ feet were fresh. The lifecycle of coal had come and made its mark and gone.

“You can see where they cut out,” Doll said. “They just entirely destroyed that mountain. It’s such a wild thing to think that strip mine land is going to be part of the solution.”

Doll thinks of it as a post-apocalyptic landscape, or maybe mid-apocalyptic, ripe for renewal, but still carrying the weight of its past. The land was gifted by people whose money was made from coal, after all.

“And, you know, it’s great that they’re giving land back,” he said. “I would prefer if it was still mountains, but if it was mountains, we couldn’t build houses on it. So yeah, it’s ridiculously complex.” He shrugged. “Bigger heads than mine.”

He squelched across the mud and back to the car. In the summer heat, two turkeys retreated into the shade of a scrubby pine grove, their tracks etched in the mud alongside hoofprints, probably from deer and elk. The place was alive, if not exactly the way it was before.

The former strip mine developments are financed in part by the Team Kentucky flood relief fund created by the governor’s office. Beyond the four projects already in motion, eastern Kentucky housing nonprofits like the Housing Development Alliance are working with landowners, local officials and the governor to secure more land in hopes of building hundreds more homes.

“Working together – and living for one another – we’ve weathered this devastating storm,” Governor Andy Beshear said last week during a press conference outlining progress made since the flood. “Now, a year later, we see the promise of a brighter future, one with safer homes and communities as well as new investments and opportunities.”

That said, nothing is fully promised just yet, and the process could take years. The homes will be owner-occupied and residents will carry a mortgage, but housing advocates hope to lower as many barriers to ownership as possible and help families with grants and loans. Applications for the developments are expected to open within a couple of months. The plans, thus far, call for an “Appalachian look and feel” that combines an old-style coal camp town and a suburban subdivision to create single-family homes clustered in wooded hollers. Though some might argue that density should be the priority, local housing nonprofits want developments that feel like home to people used to having a bit of land for themselves.

The Housing Development Alliance has built houses on mined land before, and some of them are among those given to 12 flood survivors thus far. Alongside other entities, it has also spent the year mucking, gutting, and repairing salvageable homes, often upgrading them with flood-safe building protocols. Even that comparatively small number was made possible through support from a hodgepodge of local and regional nonprofits, and the labor of the Alliance’s carpenters has been supplanted with volunteer help.

Though the Knott County Sportsplex, a recreation center built on the mineland next to Chestnut Ridge, appears to be sinking and cracking a bit, Doll said houses are too light to cause that kind of trouble. Nonetheless, geotechnical engineers from the University of Kentucky, he said, are studying the land to make sure there won’t be any unpleasant surprises. The plan is for the neighborhoods to be mapped out onto the landscape with roads and sewer lines and streetlights, all of which require the involvement of myriad county departments and private companies; then the Alliance and its partners will come in and do what they do best, ideally as further disaster funding comes down the line.

Still, all involved say that there’s no way they can build enough houses to fill the need.

More federal funding will arrive soon through the U.S. Housing and Urban Development disaster relief block grant program. It allocated $300 million to the region, and organizations like the Kentucky River Area Development District are gathering the information needed to prove to the feds the scale of the region’s need. Some housing advocates are critical of this process, though.

Noah Patton, a senior policy analyst with the Low-Income Housing Coalition, said HUD grants are too unpredictable to forge long-term plans. “One reason it’s exceptionally complicated is because it is not permanently authorized,” he said. A president can declare a disaster and direct the agency to release funds, but Congress must approve the disbursement. Although it all went smoothly in Kentucky’s case, the unpredictability means there are no standing rules on how to allocate and spend funding.

“Oftentimes, you’re kind of starting from scratch every time there’s a disaster,” Patton said.

Local development districts, such as the Kentucky River Area Development District, are holding meetings around the affected counties, urging people to fill out surveys so it can collect the data needed to apply for funding from the federal program. And HUD is overhauling its efforts to address criticism of unequal distribution of funds. Still, the people who might benefit from these block grants may not see the homes they’ll underwrite go up for a few more years, Patton said.

On the state level, housing advocates have been pushing the legislature for more money to flow toward permanent housing. Many also say the combined state, FEMA and HUD assistance isn’t nearly enough. One analysis by Eric Dixon of the Ohio River Valley Institute, a nonprofit think tank, pegged the cost of a complete recovery at around $453 million for a “rebuild where we were” approach and more than $957 million to incorporate climate-resilient building techniques and, where necessary, move people to higher ground.

Sasha Gibson has heard rumors of the new developments. She’s somewhat interested insofar as they can get her out of limbo. Until she sees these houses going up, though, they’ll be just another vague promise in a year of vague promises that have gotten her nowhere but a dusty ATV park. It’s been, to put it bluntly, a terrible year, and the moments where the family’s had hope have only made the letdowns feel worse.

“I have no hope to rely on other people,” she said. “I don’t want to give somebody else that much power over me. Because then you’ll just wind up disappointed and sad. And it’s even sadder when you have all of these little eyes looking at you.”

As Gibson waits, others long ago decided to remain where they were and rebuild either because they could or because there wasn’t another choice.

Tony Potter, who’s lived on family land in the city of Fleming-Neon since birth, has spent the past year in what amounts to a tool shed. It’s cramped and doesn’t even have a sink, but the land under it belongs to him, not a landlord or bank. It’s a piece of the world that he owns, and because a monthly disability check is his only income, he doesn’t have much else and probably couldn’t afford a mortgage or rent. Asked if he’d consider moving, he scoffed.

“You put yourself in my shoes,” he said.

He can’t believe FEMA would offer to buy someone’s land, or that anyone would take the government up on the offer. “I mean, my God, why in the hell you wanna buy the property and then tell them they can’t live on it?” he said. “What kind of fool would sell their property? Why would you want to sell something and then go rent something?”

James Hall, who also lives in Neon, lost everything but is staying put, in part because he doesn’t think it’ll happen again. The words “thousand-year flood” must mean something, he said. But that didn’t keep him from putting his new trailer a foot and a half higher just in case. He might bump that up to 3 feet when he has a minute. Through it all, he’s kept his dry sense of humor. “If the flood comes again,” he said, “I’m gonna get me a houseboat.”

That kind of outlook buoys Ricky Burke, the town’s mayor. He said the community’s used to flooding – the city sits in a floodplain at the intersection of the Wrights Fork and Yonta Fork creeks – but last year’s was by far the worst. Water and mud plowed through town with enough force to shatter windows. People went without water and electricity for months in some places. A few buildings, like the burger drive-in on the corner at the edge of town, have been repaired, but others remain gaunt and empty.

Still, Burke, a diesel mechanic who was elected in November, is confident the town will pick itself up. He’s heard talk that Neon might need to move some of its buildings, that a return to form simply isn’t viable. He’s dismissive of such a notion. What Neon needs, he believes, is a big party, and he’s planning to celebrate the community’s resilience with flowers, music, and a gathering on the anniversary of the flood.

“These people in Neon ain’t going nowhere,” he said.

Some folks, through persistence, hard work, and a bit of luck, have moved into new homes.

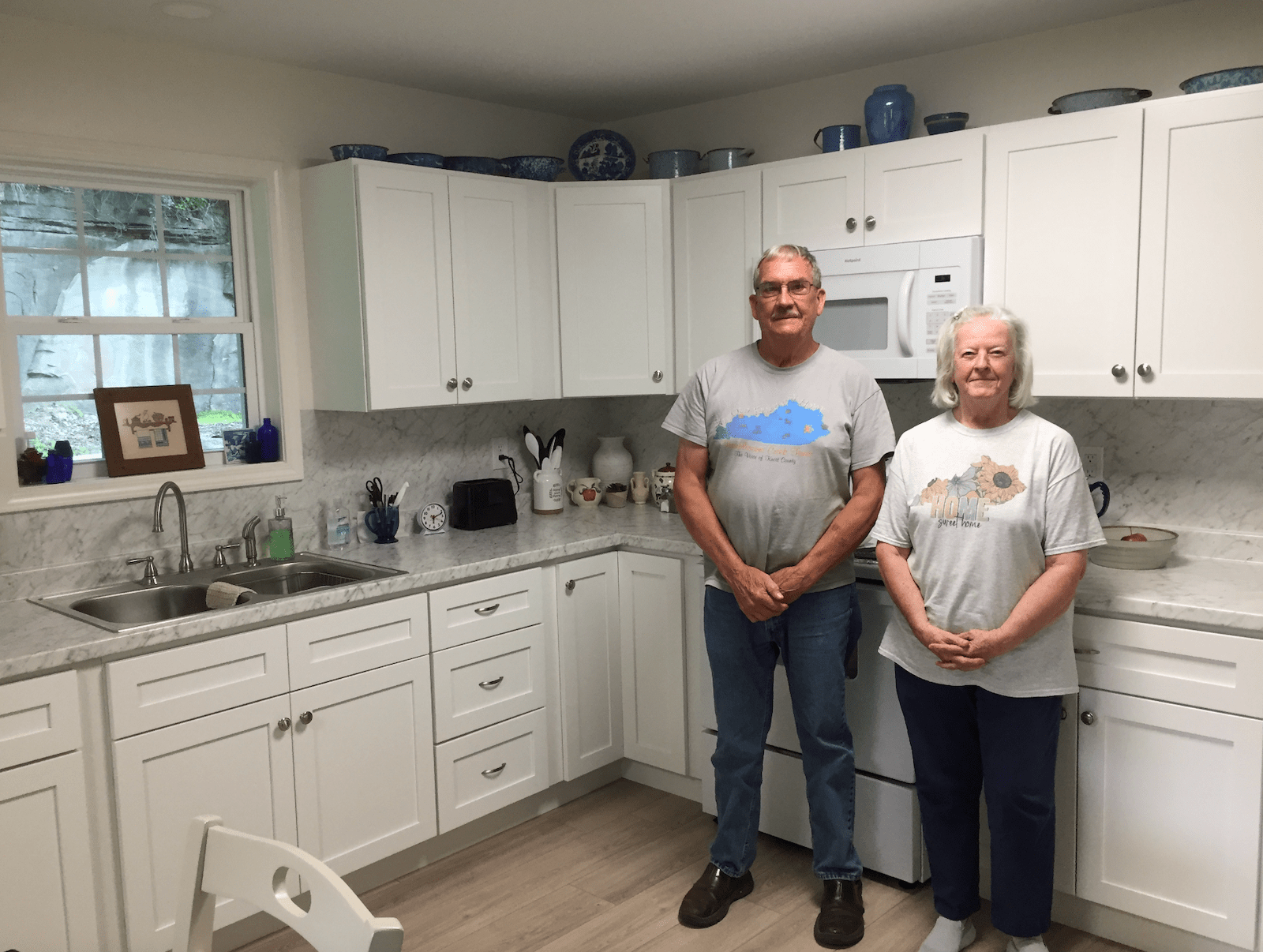

Linda and Danny Smith got theirs from Christian Aid Ministries, a Mennonite disaster relief group, though construction started a couple months later than planned because it ended up taking awhile to figure out exactly where the floodplain was. It was built on their land at the end of a Knott County road called, whimsically, Star Wars Way. According to the Smiths, the group, which was from out of state, nearly ran out of time before having to return home and only just finished the job before leaving. They left so quickly that Danny Smith said he still needed to paint the doors. He isn’t complaining, though. Other homes were left half-done, their new owners left searching high and low for someone to finish the job.

Although grateful for the help that put a roof over his head, Smith got a little tired of dealing with all the people who came to heal his body, his spirit, and his mind even as he completed mounds of paperwork and made calls to anyone he thought might help. “One guy, he kept insisting that I needed to go talk to someone,” he recalled. “And I said ‘who?’”

The man suggested that Danny talk to a therapist. He laughed at the recollection. It was a laugh heard often around here, the sound of a tired survivor who’s already assessed their own hierarchy of needs many times over. “I said, ‘You know, I don’t need nothing done with my mind. I need a home.”

Despite the frustration, the Smiths are piecing their lives back together, a little bit higher up off the ground than they were before. Christine White is praying for a similar outcome, and thinks she can finally see it on the horizon. The occasional nightmare aside, she’s felt pretty good these days.

FEMA gave her $1,900 awhile back to demolish her house and closed her case, leaving her high and dry. She called housing organization after housing organization until CORE, a national nonprofit that assists underserved communities, agreed to build a small home on a piece of land she owns in Floyd County. Construction began earlier this month. White, who spends her time volunteering at a local food bank, calls it a miracle. “You just gotta go where the Lord leads you,” she says. But it’s not built yet, so she’s trying not to count her chickens.

Parker Hobson contributed to this story.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Old nightmares and new dreams mark the year since Kentucky’s devastating flood on Jul 27, 2023.

Climate Connections is a collaboration between Grist and the Associated Press that explores how a changing climate is accelerating the spread of infectious diseases around the world, and how mitigation efforts demand a collective, global response. Read more here.

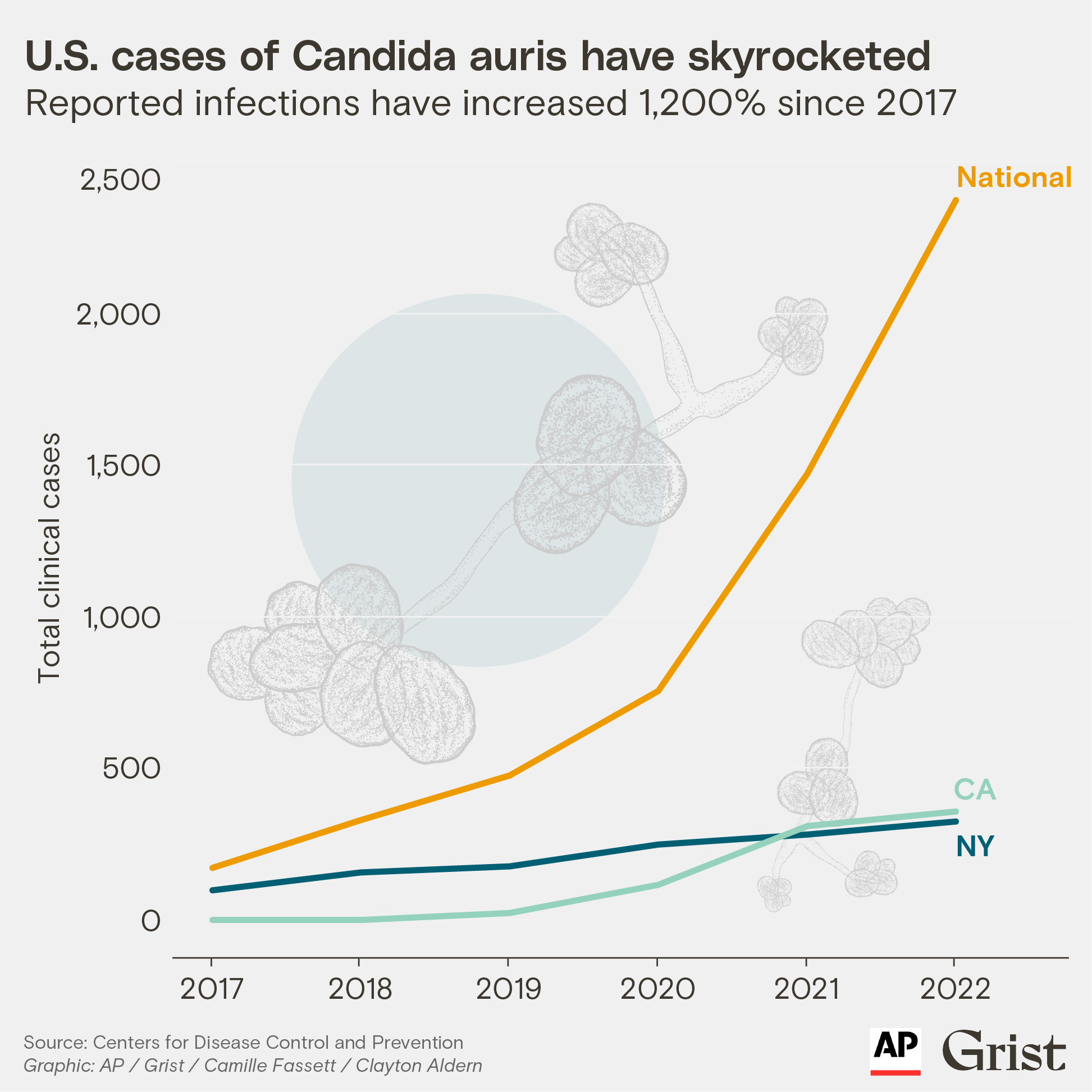

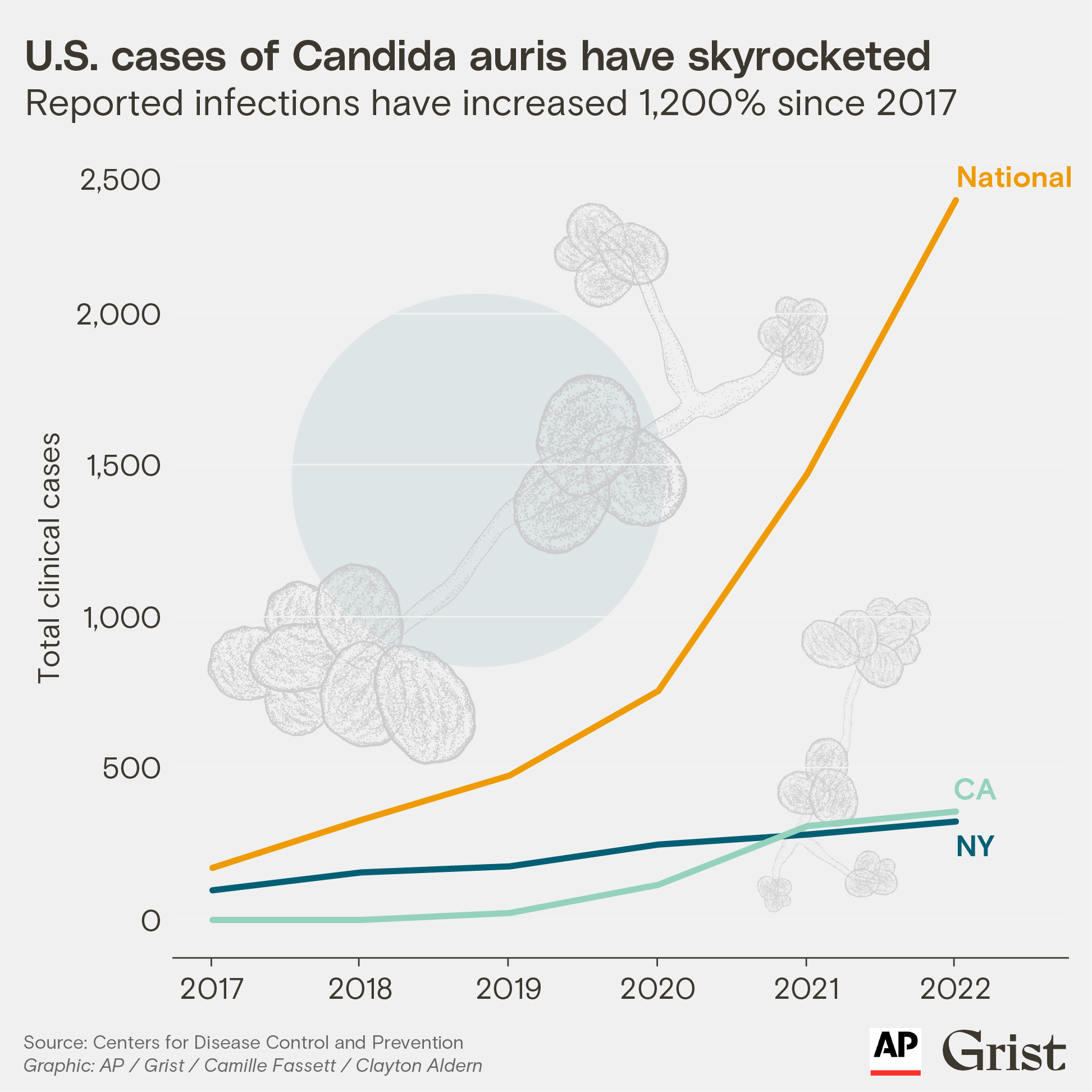

In 2016, hospitals in New York identified a rare and dangerous fungal infection never before found in the United States. Research laboratories quickly mobilized to review historical specimens and found the fungus, called Candida auris, had been present in the country since at least 2013.

In the years since the discovery, New York has become an epicenter for C. auris infections. Now, as the illness spreads across the U.S., a prominent theory for its sudden explosion has emerged: climate change.

As temperatures rise, fungi can develop tolerance for warmer environments — including the bodies of humans and other mammals, whose naturally high temperatures typically keep most fungal pathogens at bay. Over time, humans may lose resistance to these climate-adapting fungi and become more vulnerable to infections. Some researchers think this is what is happening with C. auris.

[Read next: A brain-swelling illness spread by ticks is on the rise in Europe]

When contracted, the fungus can cause bloodstream, wound, and respiratory infections, and other severe illnesses. Though not usually dangerous for healthy people, it can be an acute risk for older patients and others with preexisting medical conditions. The mortality rate has been estimated at 30 to 60 percent, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC, and it’s a particular risk in health care settings where infections can easily spread, such as hospitals and nursing homes.

The pathogen was first identified 14 years ago in Japan and then found to have emerged spontaneously in three countries on three continents: Venezuela, India, and South Africa. In the U.S., the most cases last year were found in Nevada and California, but the fungus was identified clinically in patients in 29 states. New York remains a major hotspot.

Fungal disease expert Arturo Casadevall, a microbiologist, immunologist, and professor at Johns Hopkins University, said that humans normally have tremendous protection against fungal infections because of our temperature. “However, if the world is getting warmer and the fungi begin to adapt to higher temperatures as well, some … are going to reach what I call the ‘temperature barrier,’” he said, referring to the threshold at which mammals’ warm body temperatures usually protect them from infection.

When C. auris was first spreading in the U.S., cases were linked to people who had traveled here from other places, said Meghan Marie Lyman, a medical epidemiologist for mycotic diseases at the CDC. Now, she said, most cases are acquired locally, generally spreading among patients in health care settings.

In the U.S., there were 2,377 confirmed clinical cases diagnosed last year — an increase of more than 1,200 percent since 2017. C. auris is also becoming a global problem. In Europe, a survey last year found case numbers nearly doubled from 2020 to 2021.

“The number of cases has increased, but also the geographic distribution has increased,” Lyman said. She noted the skyrocketing numbers represent a true increase in cases, not just a reflection of better screening and surveillance processes.

In March, a CDC news release noted the seriousness of the problem, citing the pathogen’s resistance to traditional antifungal treatments and the alarming rate of its spread. Public health agencies are focused primarily on strategies to mitigate transmission in hospitals and other health care settings.

“It’s kind of an active fire they’re trying to put out,” Lyman said.

Dr. Luis Ostrosky, a professor of infectious diseases at McGovern Medical School at UTHealth Houston, thinks C. auris is “kind of our nightmare scenario.”

“It’s a potentially multidrug-resistant pathogen with the ability to spread very efficiently in health care settings,” he said. “We’ve never had a pathogen like this in the fungal-infection area.”

As temperatures rise, fungi can develop tolerance for warmer environments — including the bodies of humans and other mammals.

C. auris is nearly always resistant to the most common class of antifungal medication. Occasionally, it can be resistant to the broadest spectrum antifungal.

“I’ve encountered cases where I’m sitting down with the family and telling them we have nothing that works for this infection your loved one has,” said Ostrosky, who has personally treated about 10 patients with the fungal infection but has consulted on many more. He says he has seen it spread through an entire ICU in two weeks.

As researchers, academics, and public health groups investigate theories that explain the emergence of C. auris, Ostrosky said that climate change is the most widely accepted one. Global temperatures rose about 2 degrees Fahrenheit between 1901 and 2020, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the global average temperature is expected to continue trending up in coming decades. Climate change has been found to make heat waves more likely, and a recent study found that temperatures crossing the103-degree mark — classified as “dangerous” heat by the National Weather Service — will be three to 10 times as common by 2100.

The CDC’s Lyman said it’s possible the fungus was always among the microorganisms that live in the human body, but because it wasn’t causing infection, no one investigated until it recently started causing health problems. She also said there are reports of the fungus in the natural environment — including soil and wetlands — but environmental sampling has been limited, and it’s unclear whether those discoveries are downstream effects from humans.

“There are also a lot of questions about there being increased contact with humans and intrusion of humans into nature, and there have been a lot of changes in the environment, and the use of fungi in agriculture,” she said. “These things may have allowed Candida auris to escape into a new environment or broaden its niche.”

Wherever and however it originated, the fungus poses a significant threat to human health, researchers say. Immunocompromised patients in hospitals are most at risk, but so are people in long-term care centers and nursing homes, which generally have less access to diagnostics and infection-control experts.

[Read next: How climate change is making us sick]

The disease is still quite rare, and many doctors aren’t even aware it exists. It’s also difficult to diagnose, with the most widely used blood test missing about half of all cases, according to Ostrosky (he notes that a newer, better test is now available, though it is expensive and not widely available). In addition, the most common symptoms of infection include sepsis, fever, and low blood pressure — all of which can have any number of causes.

Infections like C. auris have also entered the public discourse thanks to the HBO series The Last of Us, the hit drama about the survivors of a fungal outbreak. An infection that can transform humans into zombies is a work of fiction, but addressing climate change that’s altering the kinds of diseases seriously threatening human health is a real-world challenge.

“I think the way to think about how global warming is putting selection pressure on microbes is to think about how many more really hot days we are experiencing,” said Casadevall of Johns Hopkins. “Each day at [100 degrees F] provides a selection event for all microbes affected — and the more days when high temperatures are experienced, the greater probability that some will adapt and survive.”

Adds Ostrosky of UTHealth Houston: “We’ve been flying under the radar for decades in mycology because fungal infections didn’t used to be frequently seen.”

* * *

Explore more from the Climate Connections series:

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline In the US, a fungal disease is spreading fast. A hotter climate could be to blame. on Jul 27, 2023.