The United States and human civilization face a nature crisis. Our ecosystems are degrading alarmingly,…

The post Ecosystem Health Check: A Look Ahead at the US’ First National Nature Assessment appeared first on Earth911.

The United States and human civilization face a nature crisis. Our ecosystems are degrading alarmingly,…

The post Ecosystem Health Check: A Look Ahead at the US’ First National Nature Assessment appeared first on Earth911.

As Maui sweeps up the ashes from America’s deadliest wildfire, water-logged Vermont can’t get a respite from the rain. Meanwhile, Arizona just declared a heat emergency and large swaths of the country are seeing their thermometers climb to levels the government considers dangerous.

Amid 2023’s summer of climate discontent, the nation’s grandest plan yet to rein in runaway greenhouse gas emissions and fight climate change is turning one: the Inflation Reduction Act.

“This bill is the biggest step forward on climate ever,” said President Biden, one year ago today, just before signing the legislation, abbreviated the IRA. That White House celebration came after months of negotiation, and the President’s supporters greeted him with cheers, music and pomp.

Wide-ranging in scope, the Inflation Reduction Act included changes such as allowing the government to negotiate prescription drug prices and raise taxes on corporations, but at its heart, the IRA is a climate bill. Inside the 730 page bill are close to $369 billion in spending and tax credits designed to move the United States toward a cleaner energy future. A recent report from the Rhodium Group, an analytics firm that tracks greenhouse gas emissions, estimates that the IRA will reduce national greenhouse gas emissions to 29 to 42 percent of 2005 levels by 2030.

Compared to the fanfare that occurred at signing, the year since the IRA was enacted has been outwardly much quieter — with a recent Washington Post and University of Maryland poll finding that 7 out of 10 Americans had heard little to nothing about the measure since it passed. But, largely behind the scenes, experts say that the Biden administration has been implementing the IRA at a scorching pace.

Experts caution against reaching conclusions after the first year of a plan that is meant to span a decade. But they say there are both achievements worth marking — such as the torrent of private-sector investment the bill spurred and the impact it’s already had on Colorado river conservations — as well as future challenges to stay focused on, specifically whether projects can be permitted quickly enough. All the while, the Biden administration must battle not only a divided-Congress, but public disconnect from the bill.

Popular and legislative support for further climate action will be key to meeting the White House’s goal of an at least 50 percent emissions cut by the end of the decade. Public ambivalence toward the IRA could be a good thing if the bill falters because it may avoid souring Americans on climate policy writ large, says critic Doug Holtz-Eakin, president of the center-right American Action Forum and former director of the Congressional Budget Office. However, IRA supporters conversely fear that a lack of public awareness about the impacts of the IRA could make passing future climate legislation more difficult.

For now, the administration’s focus has been on making the IRA a success.

“One doesn’t expect the federal government to move quickly, but they have,” said Ramanan Krishnamoorti, vice president of energy and innovation at the University of Houston. After passing the IRA, he doubted the administration could stand up such a massive piece of legislation in such a short period of time. “I was extremely skeptical that they would actually be where they are today.”

The government has spent much of the last year laying the groundwork for dispersing IRA funding and enacting its tax incentives. That has required the government to both revamp old programs, such as the electric vehicle tax credits, and build entirely new ones. Columbia University and the Environmental Defense Fund have so far logged 150 IRA-related actions that the federal government has taken, ranging from the Environmental Protection Agency awarding climate pollution reduction grants, to the Department of Agriculture opening applications for its rural energy in America program.

“We’ve been thinking about year one as phase one of the IRA,” said Holly Bender, chief energy officer at the Sierra Club. She said the government has had to stand up hundreds of new funding streams, programs and teams within federal agencies. That effort, she said, has been “incredibly successful” and puts the government in a position to “have the money start flowing out the door.”

But Holtz-Eakin doesn’t see the administration’s ability to distribute IRA funding as an inherent measure of effectiveness. “It’s easy to shovel money out the door,” he said. “They’re far from done.”

There have, however, been some more immediate, tangible results of the legislation.

On a pragmatic level, the federal government has been adding staff in order to implement the legislation. This is true at climate-facing entities such as the Department of Energy, but also agencies that are less-often linked to climate policy, including the treasury, which is charged with outlining the rules for the litany of tax incentives that the law called for.

Krishnamoorti also highlighted another overlooked aspect of the IRA: its impact on the Colorado river. The IRA included $4 billion for water management and conservation efforts in the Colorado River Basin, which has already helped states settle long-fought negotiations over how to reduce water use in the river. The agreement reached this May allocated $1.2 billion to cities and irrigation districts in Lower Basin states in exchange for them using less water.

“The agreement that the states came to was in large part because they anticipate this funding coming,” said Krishnamoorti.

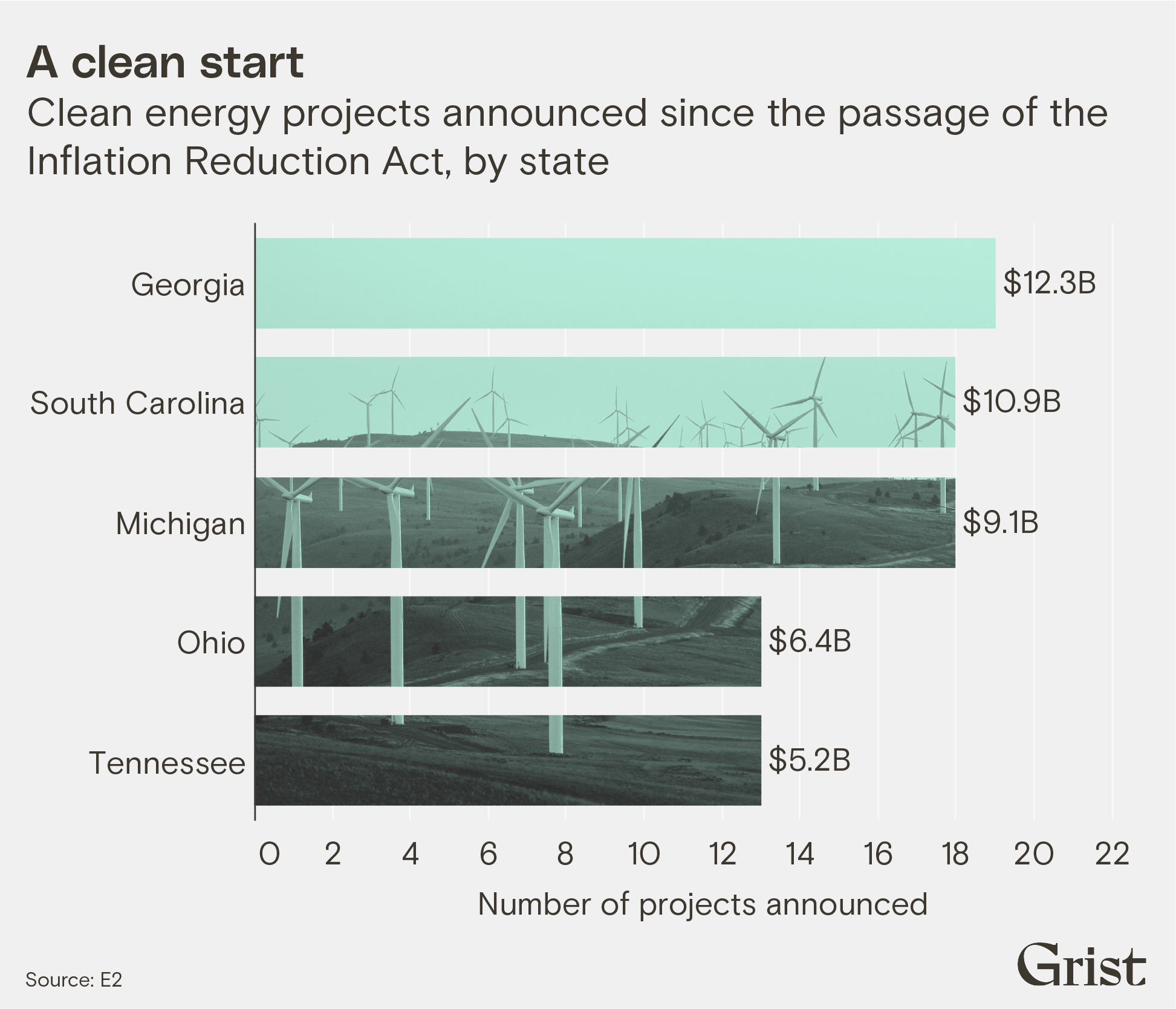

But experts agree that perhaps the most pronounced first-year effects of the IRA has been a deluge of investment announcements from the private sector. Just last week, for instance, Maxeon Solar Technologies publicized a $1 billion plan to manufacture solar cells and panels in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Overall, companies have trumpeted more than $86 billion in IRA-related investments since the bill was passed, according to E2, an organization that has been tracking businesses’ response to the legislation. The White House puts that number even higher, at $236 billion of planned investments in the electric vehicle, battery and clean energy sectors, where the commitments have been particularly pronounced.

“The responsiveness of industry to these new incentives and financial support I think demonstrates the depth of the appetite for an American manufacturing renaissance,” said Trevor Higgins, senior vice president at the Center for American Progress think-tank. He was previously a member of Sen. Dianne Feinstein’s (D-CA) staff and helped shape the IRA.

To a certain extent, companies were already moving toward a lower-emissions future, so it’s hard to pinpoint exactly how much of the IRA is driving the investment decisions. But, many businesses and politicians have specifically cited the legislation as motivation. In West Virginia, companies have broken ground at two major battery manufacturing sites.

“These types of investments are exactly what I had in mind when I wrote the IRA,” Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV), a key swing-vote on the legislation, said in a statement. He also vowed to “continue to fight the Biden Administration’s unrelenting efforts to manipulate the law to push their radical climate agenda.”

Manchin’s home state of West Virginia is set to see some $1.3 billion in private-sector dollars from the IRA, according to E2 data, and four of the top five states where investments are planned have Republican governors. Supporters of the IRA say that projects in Republican-led states will at least partially insulate the bill from politically motivated rollbacks.

“Any administration that comes in and reverses IRA provisions will lead to a lot of job destruction, primarily in red states,” said Anand Gopal, executive director of policy research at Energy Innovation Policy & Technology, a energy and climate think tank.

Republicans have nonetheless tried to dismantle aspects of the IRA since taking control of the house this year. According to Roll Call, at least four house bills have taken aim at the IRA, especially the EPA’s $27 billion Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund. And until projects are fully funded and physically built, many of the first-year impacts of the IRA remain vulnerable to a shift in political winds.

In some ways, the IRA could also prove to be a victim of its own progress. Bender, with the Sierra Club, says that the sheer number of new programs has been difficult for eligible entities to navigate. There’s a big capacity gap she said, especially for smaller nonprofits or companies.

“It’s [difficult] to find a person who can understand the programs, read the eligibility criteria, check the application dates, and then apply for funding,” she said, adding that the Sierra Club is working with its partners to “make sure that anyone who wants to access IRA programs is able to do so without a huge administrative burden.”

Then there’s the actual, physical building that needs to happen. Once a project is approved for funding or credits, worries shift to whether it will run into regulatory snags such as permitting. Easing that process is an area experts say the administration has not made much headway on in the first year of the IRA.

“The most likely bottleneck going forward is going to be permitting,” said John Coeqyut, the federal policy team director at RMI, a nonprofit working to accelerate the clean energy transition. “We are concerned that not enough will be done to clear the way for the transition.”

John Podesta, who President Biden tapped to lead the administration’s IRA efforts, addressed so-called permitting reform in remarks this May. “We’ve seen some recent wins,” he said, pointing to the Department of Energy’s move toward accelerating electricity transmission line permitting. But he also called on Congress to pass reforms that have been hung up for months.

“This administration is doing all we can with the tools we have,” said Podesta. “But frankly, we could use more tools to go even further and faster.”

As far as getting more legislation passed, the administration is up against both a divided-Congress and limited public awareness about the effects of the IRA. Less than a third of Americans say they’ve heard of the bill since it passed and even President Biden acknowledges that the IRA has thus far failed to grab people’s attention.

“I wish I hadn’t called it that,” he said at a fundraiser in Utah last week. “It has less to do with reducing inflation than it has to do with providing alternatives that generate economic growth.”

Critiques from environmentalists about the bill’s concessions to fossil fuel interests also remain unresolved after year one. There are, for instance, outstanding questions on issues such as hydrogen tax credits, the wording of which could affect the climate-impacts of the IRA because it could encourage investment in fuels that are derived from natural gas versus renewable energy. “That one is taking a little bit more time,” said Gopal. “But I think rightfully so.”

That said, there ishope among advocates that Americans will begin to feel the impacts of the IRA more directly in year two. Perhaps most notably, the Department of Energy has issued guidance for a range of home energy rebates that states are expected to begin dolling out over the coming year.

“These rebate programs are really important because they are a way for low and moderate income households to be part of this transition,” said Ari Matusiak, the CEO of Rewiring America, an electrification nonprofit. “We want to make sure those programs are being stood up and well utilized by the people who can most benefit from them.”

The ultimate test of the IRA, though, will be how quickly and how deeply it reduces greenhouse gas emissions. Holtz-Eakin says he’ll be watching the Energy Information Administration’s annual release of data as a gauge for the amount of renewable energy being brought to homes and businesses across the country. “If that hasn’t moved by year three, the advocates are going to start getting nervous,” he said. “How quickly can you move the needle, and as a result retain the support you have.”

Anand Gopal, with the Energy Innovation Policy & Technology, says the IRA remains on track to meet his organization’s projection that the bill will cut emissions by 37 to 41 percent below 2005 levels by 2030. Nothing in the first year of the IRA, he says, has changed that trend toward a cleaner energy future.

Former Congressman Bob Inglis (R-SC) was once a climate change skeptic and is now a champion of climate solutions. To him, whether the IRA gets credit for the transition or not doesn’t detract from the progress it will likely lead to.

“When people start seeing it roll out in projects, they won’t know that it came from the IRA,” Inglis said. “[But] the IRA is going to deploy a lot of wind and solar and that’s an accomplishment that people are going to look back and be proud of.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Biden’s landmark climate law turns one today. Here’s what you missed. on Aug 16, 2023.

In July, a historic marine heat wave descended upon the Florida Keys. Unprecedented coral bleaching ensued within the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS), which boasts the largest coral barrier reef within the continental United States. With high temperatures predicted to persist until October, scientists worry about potential harm to the entire ecosystem.

Beginning in mid-July, sea temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea were up to 3.5°F warmer than usual, noted a Mission: Iconic Reefs (MIR) fact sheet emailed to EcoWatch. In South Florida, the marine heatwave hit a record-breaking 95˚F – the warmest ever since recording began. One water temperature buoy, in nearby Everglades National Park, even hit a “hot tub temperature of 101.19°F” with other triple-digit reads nearby.

“The level of warmth we are seeing today is only possible because of the warming over the past 150 years due to human activity,” said Dr. Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist at nonprofit research institute Berkeley Earth, The New York Times reported.

As the planet’s largest heat sink, the ocean has absorbed more than 90% of the excess heat generated by human activities like deforestation and the burning of fossil fuels. “The more we burn fossil fuels, the more excess heat will be taken out by the oceans, which means the longer it will take to stabilise them and get them back to where they were,” Copernicus climate scientist Dr. Samantha Burgess told BBC News.

Notably, average sea temperatures for this time of year should range between 73°F to 88°F, the fact sheet said. Critically, 23°F to 84°F is optimal for reef-building corals, the coral restoration team noted, and even a 1.8°F rise in temperature can cause coral bleaching.

Corals are colonial animals that contain symbiotic algae within their tissues called zooxanthellae. The latter provides corals with their namesake color and over 85% of their energetic needs by photosynthesizing. After several weeks of adverse ocean conditions – such as during the current marine heat wave – corals will expel their symbiotic algae to conserve energy. This causes the corals to appear whitish, or “bleach,” and struggle to meet their energetic needs.

According to NOAA, this year’s bleaching event in FKNMS is considered a “mass bleaching” because it covers hundreds of kilometers or more and was driven by prolonged anomalously warm ocean temperatures. While patchy and site-specific, bleaching was reported throughout the Florida Keys – in both wild and restored corals, as well as within in situ restoration nurseries. The Coral Restoration Foundation reported the “unimaginable – 100% coral mortality” of restored corals on Sombrero Reef, a restoration site they’ve been working on for over a decade, and the loss of almost all the corals in their Looe Key Nursery in the Lower Keys.

“It’s honestly really depressing–gut-wrenching, heartbreaking, soul-breaking kinda stuff,” said Andrew Ibarra, a NOAA-Affiliate MIR marine stewardship and monitoring specialist. Ibarra found iconic Cheeca Rocks, his favorite reef, “completely bleached out.” He reported only one species of coral not completely stark white. Additionally, snorkeling during the height of the heatwave, he witnessed “all the brain corals, boulder corals, staghorn – all outplanted, all recently dead.”

While the Florida Reef Tract has bleached mildly annually since 2011, paling and bleaching in FKNMS to this degree occurred weeks earlier than usual. Bleaching doesn’t always lead to death, but can if conditions don’t improve quickly enough. “The coral is essentially starving until temperatures lower and symbionts recolonize” within coral tissues, the MIR fact sheet said. Furthermore, heat stress makes corals more susceptible to coral diseases, and MIR partners have observed “high levels of disease at many reefs.”

High temperatures aren’t the only worry. “Heat does a lot of things besides causing fish to overheat and die,” explained Ross Boucek, Florida Keys initiative manager at Florida Keys’ nonprofit Bonefish and Tarpon Trust (BTT).

Warm water holds less oxygen than cool water, and this year’s extreme temperatures have led to “hypoxic” water conditions in many areas. According to NOAA, “hypoxia” refers to low or depleted oxygen in a water body.

“All plants and animals need oxygen to live,” said Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute program manager Tom Matthews. Therefore, hypoxic areas become “dead zones” when oxygen levels decline below the levels needed by species to live. In these areas, life cannot be sustained.

The hot water also promotes the growth of phytoplankton and algae that deplete the water’s oxygen levels at night and smother corals and sponges, he added. Finally, heat can also kick bacteria and other microbes into overdrive. This increases the nutrient load in the water, which then causes algae blooms that further decrease oxygen, Matthews added.

Other marine species have shown signs of heat stress and suffocation due to hypoxia. Matthews explained, “The hot still waters cause a cascade of disturbances that harm numerous species in the nearshore hardbottom habitat.”

In mid-July, paddle boarders and boat captains reported dead fish and disintegrating sponges floating inshore and offshore – presumably overheated or suffocating in deoxygenated water. Seagrasses are stressed, conchs are dying, soft corals (gorgonians) are disintegrating and harmful algae blooms are becoming more frequent, local scientists reported.

“The giant barrel sponges that are so iconic on Florida reefs are one of the species that are susceptible to bleaching and could experience fatal losses of their symbiotic algae during this heat event,” said Bobbie Renfro, a Florida State University Ph.D. candidate studying sponges in the Florida Keys and Panama. The latter is currently also in a catastrophic bleaching event, and Renfro observed “whole populations of sponges [there] that are bleaching right alongside the corals and then proceeding to disintegrate.”

Sponges are the “unrecognized water pumps and super filters of our marine ecosystem,” added Matthews. They, along with corals and seagrasses, also serve as critical nursery habitats for many important fish and marine life species. Therefore, catastrophic losses of these could cause a cascade of ecological harm.

“In a nutshell, it isn’t just the heat, but the combination of all of these things that dictate what species die, and where mortalities are most intense. It is hard to say what the worst-case scenario is because we haven’t ever had anything like this,” Boucek said.

Scientists hope that the worst of the heat peaked in July but are still concerned about how long it will last. In fact, this is the longest-lasting marine heatwave in the region since 1991, the MIR fact sheet reported. It called the heat “remarkably persistent,” with a 70-80% chance that extreme ocean temperatures will continue until October.

The El Niño will also continue to bolster the extreme ocean heat.

If the heat drives coral, sponge and other ecosystem mortality, the coral reef habitat in the Florida Keys could begin to erode. This would mean the loss of ecosystem services upon which humans rely: food, storm protection, tourism and biodiversity.

“The biggest unknown from this heatwave is what it could do to our habitats,” said Boucek. “We are in uncharted territory with this heat, so it is hard to predict what our systems will look like on the back end of this.”

The post Extreme Heat in Florida Keys Threatens an Entire Ecosystem appeared first on EcoWatch.

Inside the Hawaiian Canoe Club hale, or house, volunteers set out boxes filled with donated diapers, toiletries, and clothes for families to pick up. Against a backdrop of the bright blue waters of Kahului Harbor and the cloud-covered West Maui mountains, they filled trucks with gasoline cans, propane tanks, and coolers of ice behind a sign reading “Donate — We have convoy to Lahaina.”

A mile away, outside the entrance to the shelter at War Memorial Gym, a steady stream of cars pulled up along pallets stacked high with supplies. Drivers called out through their windows how many people they were delivering to, their ages and needs. An assembly line of volunteers led by Kanaka Maoli, or Native Hawaiians, stuffed each vehicle with donations before moving on to the next.

And on a corner lot in a neighborhood near Maui High School, a Hawaiian family turned their front yard into a distribution center, collecting necessities for the dozens of people crammed into the homes of family or friends or living in their cars nearby. The family had taken to affectionately calling a large trailer in front of the house, where people could sift through carefully organized boxes of clothing, the “walk-in closet.”

Across Maui, community hubs like these have cropped up with dizzying speed in the days since wildfires swept through Maui on August 8, killing at least 99 (with the death toll expected to rise), destroying more than 2,200 buildings, and displacing thousands. They are led by the community, and grounded in the deeply held Hawaiian values of caring for, and sharing with, one another. But they are also driven by a growing concern that the people still in their homes around Lahaina and displaced across Maui are not getting enough help from authorities.

“A lot of people are mobilizing,” Leo Nahenahemailani Smith, one of the volunteers at the canoe club, said Sunday. “With aloha, you give whether people ask or not, it’s in our nature.”

In Wisconsin on Tuesday, President Joe Biden, noting that the wildfire was the deadliest the nation has seen in more than a century, vowed that the people of Maui will get all the help they need. “Every asset, every asset they need will be there for them, and we’ll be there on Maui as long as it takes, as long as it takes and I mean that sincerely.”

But in the week since the fires ravaged West Maui, much of the burden of helping survivors has fallen on local volunteers, with government assistance noticeably absent in some places.

On Sunday, volunteers arrived at the canoe club at 7:30 a.m. to put out boxes of donations. Others made calls to area shelters to see what they needed, then dispatched drivers with supplies. Most had been working for five days straight, sometimes 12-hour shifts. A few had set to work after helping neighbors and relatives fend off the fires that burned upcountry Maui.

A steady flow of people passed through the hale dropping off donations. A family from Hana, a two-hour drive away, stopped by on their way to Costco, asking what they could provide. They returned a couple hours later with propane and ice. A young man offered some two-way radios. A group of firefighters from Honolulu filled a truck with cases of water before heading off to a shelter. A couple with a baby strapped into the back seat of their car dropped off gas cans they’d filled themselves.

Others came seeking items for themselves or for those they were caring for. A woman asked about baby wipes, which she hadn’t been able to find. A man who lost his home picked out a few shirts and shorts. A couple whose house had been spared in the upcountry fires filled their truck with supplies for their neighbors, all of whom had lost their homes.

Sunday afternoon, volunteers cooked and packed up hot meals before a convoy of pickup trucks arrived to transport food, gasoline, propane, and coolers of ice to Lahaina and the surrounding areas.

It is unclear how many people remain in Lahaina, but two sources estimated the number might exceed 1,000. Access to West Maui remains restricted, and the few entry points have at times been chaotic and tense. At first, residents were told they would not be allowed back if they left, so many chose to stay. Some had no other choice.

“They have nowhere else to go,” said Tiare Lawrence, one of the volunteers at the Hawaiian Canoe Club. Many of her relatives lost their houses, including one that had been in the family for four generations.

Others have been afraid to leave their homes for fear of looters and thieves. “A lot of people are hunkering down just to protect their homes,” Lawrence said.

Supplies are being taken into West Maui by people who can prove they live there or who have special passes. Those without them are finding workarounds. In the first days of the recovery, brigades of boats and jet skis ferried supplies.

So many deliveries of clothes and household goods have arrived that some are being turned away. But with power still out in portions of West Maui, volunteers have shifted their focus to the supplies needed to sustain residents in the long-term, like fuel for generators, ice, solar lamps, batteries, and water. West Maui residents have been warned against drinking the water even if it’s boiled because of wildfire contaminants. “That’s the hardest stuff to find right now, and it’s the stuff we most need,” said Chase Pico, a volunteer at the distribution site outside the War Memorial shelter.

Hubs inside the restricted zone offer food, water and other essentials, but volunteers worry they are not reaching people who can’t leave their homes or who live in more remote areas. They’re driving on back roads, going neighborhood by neighborhood to find people who aren’t being reached by state and federal authorities. Many told Grist they’re not seeing any indications of government aid around Lahaina beyond the disaster area.

“I haven’t seen people in uniform, only locals in trucks [making deliveries],” said Cheyanne Kaawa, who has spent days shuttling supplies into Lahaina and couldnʻt understand why Governor Josh Green had not yet requested U.S. military assistance. The Hawaii National Guard is on the ground on Maui, but the governor has not yet requested active-duty troops. The governor’s office did not return two requests for comment.

With multiple storms forecast to hit the area this week, Kaawa worried that the prolonged wait is endangering survivors, especially ones that lost their roofs. “Today is day eight, three fires are still going, our water is contaminated, and a lot of people still have no power or ways to communicate,” she said. “Vulnerable homes and lives that were spared in the first fire might not make it through the next storm.”

Paul Kaʻuhane Luʻuwai, head coach of the canoe club and one of the convoy drivers who had made multiple delivery trips, said on Sunday that he also had not seen anyone from FEMA in the neighborhoods. His family lost seven houses in the fire. “I want to know where the hell is the government,” he said. “Yes, theyʻre looking for remains, but it’s been five days. Where are they?”

A FEMA spokesperson said that the agency was providing the services that the state had requested of them, including registering residents at shelters so that they can receive aid, and that it has urban search and rescue teams in Lahaina focused on the disaster site.

Asked why the Red Cross had not yet gone into the restricted area to distribute aid and check on residents, a spokesperson for the agency, which is managing several shelters, also said they needed permission from state officials to do so.

The need for aid extends well beyond those who remain in Lahaina. Around 2,100 people entered shelters after the fire, but countless evacuees remain dispersed across the island, staying with loved ones, in their cars, or even in tents in yards. Those who are hosting them are straining to support the displaced in addition to their own families.

Kekane and Josh Kuloloio set up a distribution center in their front yard after realizing that many people had taken shelter in homes and in parked cars around their neighborhood. Kekane said she knew of one house hosting 24 people. Theyʻd also met a man who was living in his car with his son.

The situation has put stress on the Kuloloios too, who have five children, two of them younger than 3. It’s been hard to find diapers because of the concentrated demand. “Itʻs an island-wide crisis,” said Josh Kuloloio.

He’s also frustrated by how difficult the government had made it to bring help or to even volunteer at official shelters.

“FEMA knows nothing about our culture of taking care of everybody, of nobody left behind,” he said. “They’re butting up against who we are.”

Similar frustrations came up at the canoe club. A woman appeared with boxes of homemade fruit cups that she tried to donate at the War Memorial Gym shelter but had been turned away. “The aunties in there are tired of eating canned food, but they won’t even let me give them fruit,” she said.

Despite restrictions that many residents say limit them from caring for their own, community volunteers continue finding ways to offer whatever solace they can. When a little boy arrived at the canoe club missing the toy trucks he’d lost in the fire, volunteers rummaged through donations until they found a Hot Wheels car for him.

“Itʻs just a little bit of normalcy, a tad of comfort,” said Tahina Kinores, one of the coordinators. That evening, she stayed three hours past when the hub was scheduled to close, so that families who didn’t want to be seen asking for help could come get supplies in private.

Around 8:30 p.m. Kinores and some close friends who had been there for 13 hours moved all the boxes back into the hale. Someone turned on a reggae song, they opened beers, and swayed to the music. It was only a brief reprieve. The next morning, they’d do it all over again.

Grist senior staff writer Anita Hofschneider contributed reporting to this story.

This story has been updated after FEMA clarified that it has urban search and rescue teams at the disaster site.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline ‘Where are they?’ With government aid still spotty, Maui locals funnel supplies to fire survivors on Aug 15, 2023.

The water shortage crisis on the Colorado River is improving, but it’s far from over.

That was the message from the Biden administration on Tuesday, as officials announced they would loosen water restrictions on the river in 2024. Thanks to robust winter snowpack that provided about 33 percent more moisture than the average year, the water levels in the riverʻs two main reservoirs have begun to stabilize after plummeting over three years. This has lessened the need for states in the Southwest to cut their water usage.

The total cuts will be about 20 percent lighter than they were last year, requiring three Southwest states and Mexico to save around 600,000 acre-feet of water — enough to supply roughly 1.2 million homes.

Even so, the administration left some mandatory restrictions in place to account for the fact that the reservoirs, Lake Mead and Lake Powell, are still emptier than they have been at almost any point in history. That’s due in large part to a millennium-scale drought that researchers believe was made much more likely by climate change. And even as federal officials eased up on mandatory restrictions, they were also preparing to dole out billions of dollars to the region’s farmers and cities in an effort to further reduce water usage on the river.

“The above-average precipitation this year was a welcome relief,” said Camille Camimlim Touton, the commissioner of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, the federal agency that oversees the river, in a press release. “We have the time to focus on the long-term sustainability solutions needed in the Colorado River Basin.”

During the past three years, as the Colorado River has dried up, the federal government has used the elevation of Lake Mead as a benchmark to determine what restrictions it needs to impose on Arizona, Nevada, and California, the three states in what’s known as the riverʻs “Lower Basin,” as well as Mexico. In practice, the state that has suffered the most under this system is Arizona, which has junior rights to the river as a result of a compromise it made in the 1960s to secure funding for canal infrastructure; it has borne almost all the early cuts.

The Biden administrationʻs announcement this week, which will move the river from a “Tier 2a” shortage back down to a “Tier 1” shortage, should give Arizona cotton farmers and Phoenix-area cities a little more breathing room next year. But the river’s long-term prognosis means that it may not be wise for farmers to start planting more fields, or for cities to keep adding new golf courses and lawns.

“I’d say it’s probably not going to help that situation much,” said Paco Ollerton, a farmer who grows cotton and other crops outside the city of Casa Grande, south of Phoenix. “The acreage has dropped quite a bit. We’re probably about 25 percent fallow in the district this year.” The easing of drought restrictions might help some farmers increase their acreage, Ollerton added, but many will hold off on replanting because they’re wary of future cuts.

Even as the Biden administration sets a more relaxed standard for 2024, officials are preparing to roll out a larger series of water cuts that will last for the next three years. These bigger cuts, which the administration hopes will lift the river out of the drought-induced crisis of the past few years, were the result of a hard-fought compromise between the seven states that use the river — and in particular between the two largest users, Arizona and California.

The announcement of the compromise plan in May brought an end to a year of tense negotiations between the states and the Biden administration, triggered by unprecedented fears that Lake Powell and Lake Mead would bottom out altogether. In that doomsday scenario, hydroelectric plants that provide power to millions of people would have shut down, and water might not have been able to move past the reservoirs at all. The compromise plan uses about $1.5 billion in drought funding from the Inflation Reduction Act to compensate farmers and cities for using less water over the next three years.

This was a welcome outcome for farmers in places like Imperial County, California, who had expected to take uncompensated water cuts for the first time in history, as well as for city leaders in Arizona, who had stood to lose a huge share of their Colorado River water during the negotiations. The compromise was only possible because of this year’s wet winter, which deposited enough snow to prop up water levels in Lake Powell and Lake Mead. With reservoirs recovering, the states could get away with more modest cuts — and pay for them with money that Senator Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona secured within the Inflation Reduction Act last year.

Even so, the compromise leaves several questions unanswered. The biggest question is how the states can reduce usage over the long term to account for the gradual aridification of the river. Farmers and cities can save water through techniques like drip irrigation or wastewater recycling, but these technologies are expensive to implement. In all likelihood, some places will have to farm less or build fewer houses. Furthermore, many tribal nations along the river still can’t access the water to which they have legal rights, and satisfying those rights could mean taking water away from other non-tribal users.

The federal government needs to hash out answers to these questions with states and tribes by the end of 2026, when the current operating guidelines for the river will expire. The Biden administration already kicked off that process last month when it asked stakeholders to weigh in on the river’s future. The negotiations won’t kick off in earnest for months or even years, but the administration’s goal is clear: avoid a repeat of the past yearʻs crisis at all costs.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Feds ease up on Colorado River restrictions — for now on Aug 15, 2023.

Some environmental professionals warn us that the time for focusing solely on climate mitigation – that is, preventing warming from happening – is behind us. Instead, they argue that cities need to begin shifting their efforts toward adaptation: responding to the impacts of climate change already happening in many parts of the country, and preparing for those that are inevitable given the current projections for rising temperatures. Even if we stopped burning fossil fuels tomorrow, there is still a 42% chance that we would overshoot our goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

Catastrophic heat waves are no longer outliers, but practically the norm. Urban areas are especially susceptible to dangerous heat waves due to a concept called the “urban heat island effect,” whereby urban areas become warmer than surrounding rural areas. In cities, dark roofs and asphalt absorb heat, and glass windows reflect sunlight onto the ground below. The lack of greenery that often categorizes cities also means less shade, and tall buildings block wind from reaching the sidewalks. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, these heat islands can be 1-7ºF warmer during the day, and 2-5ºF warmer during the night than surrounding areas.

Hundreds of millions of people already live in urban areas, and according to the Global Center for Adaptation, the urban population affected by heat will rise by 800% by 2050. Getting urban temperatures under control is an issue of equity, too, as the poorest and most vulnerable residents in cities often live in buildings with poorer ventilation or little greenery.

Along with warning systems about heat and other public information campaigns, however, some cities are making architectural and design changes to improve resilience to heat. Here are a few ways cities are innovating and adapting to the effects of heat.

To combat the urban heat islands effect in Colombia’s second largest city — which is home to 2.5 million people — the government has focused on shade coverage. The Green Corridors (or “Corredores Verdes”) project began in 2017, whereby a network of 30 shaded routes was created connecting parks and other areas of interest across the city. The routes are composed of 12 waterways and 18 roads, providing cooler cycling and walking paths for citizens. To construct the Green Corridors, citizens were trained by the Joaquin Antonio Uribe Botanical Garden to become gardeners and planted 8,800 trees and palms, as well as 90,000 other species of tropical plants to shade the areas.

Green spaces are proven to be effective at cooling cities; the UN Environment Programme states that urban parks have the ability to reduce ambient daytime temperatures in cities by about 1ºC. This cooling phenomenon is evident in the Green Corridors, where temperatures have come down by about 5.5ºF and are expected to fall by several more degrees over the coming decades. The corridors have also improved air quality and overall biodiversity in the city.

Los Angeles is hot — and, as runaway climate change progresses, it’s only going to get hotter. By the middle of the century, Los Angeles could face 22 days of extreme heat every year, according to a 2015 study.

Dark surfaces like asphalt are a major contributor to the urban heat island effect, as they absorb the sun’s rays — 80-95% in the case of dark asphalt — and emit them as heat. As part of a goal from former mayor Eric Garcetti to cool the city by 1.67ºC in 20 years, LA began a campaign to replace these dark surfaces with light ones. The city started experimenting with painting streets white with a CoolSeal coating in 2019, which was originally designed by the military to cool down spy planes and keep them hidden from satellite infrared cameras. As of August 2022, the GAF Cool Community Project finished painting 1 million square feet of roads, playgrounds, and parking lots in the Pacoima neighborhood of LA — some with murals and artwork — with a coating called Invisible Shade.

Streets that have been painted have measured 10-15 degrees cooler on average than those that are unpainted, decreasing the need for air conditioning in nearby buildings. However, because the heat reflects off of the white surface rather than being absorbed, some argue that people walking on the streets will actually experience greater heat than before, even if the surrounding area is cooler.

Since its launch in 2009, New York’s CoolRoofs project has provided paid training and work experience to New Yorkers to cover more than 10 million square feet of rooftops with a reflective covering in an effort to combat the urban heat island effect. The coating used has a high solar reflectivity — the degree to which the roof reflects visible infrared and ultraviolet rays — and infrared emissivity, which means its ability to release absorbed heat.

On an average summer day in New York, black asphalt rooftops can reach 190ºF, which is 90ºF more than the surrounding air. As a part of the city’s goal to cut carbon emissions by 80% by 2050, the project works to keep buildings cool and reduce the need for air conditioning. Some of these cool rooftops can reduce internal building temperature by 30%. The city estimates that for every 2,500 square feet of reflective roofs, NYC’s overall carbon emissions can be reduced by one ton. No-cost installations are available for non-profits, low-income housing, schools, hospitals, and other organizations.

The UAE is often known for its very high temperatures, which can reach over 120ºF, making air conditioning a necessity. In an effort to combat this heat, the city has turned to the old Arabic architectural concept of Mashrabiya, which uses latticed screens to diffuse light as it enters buildings. The 25-story Al Bahar Towers utilize this technique — the facade is covered in shades controlled by a computer, which open and close depending on the position of the sun. These “responsive facades” are coated in fiberglass and arranged in repeating patterns around the building and automatically shut off after the sun goes down. CNN reports that this method means that the buildings can use less artificial lighting and 50% less air conditioning.

Like Abu Dhabi, Greece is also turning to ancient architecture for solutions. The city of Athens plans on renovating a historic aqueduct that dates all the way back to the Roman era, with the goal of irrigating the city’s green corridors. The ancient aqueduct began in 125 AD under the emperor Hadrian and was the main source of water for the city for over a millennium, although it’s no longer used for this purpose. This warm, Mediterranean city — which has very little green space — plans to use this underground water to green areas throughout the city and help reduce average daily temperatures.

The post How Cities Are Adapting to Climate Change appeared first on EcoWatch.

Hello, and welcome to the latest edition of Record High. I’m Siri Chilukuri, a reporting fellow at Grist. Today, we’re covering the dire impact of extreme heat on livestock and the agricultural industry — as well as a potential solution some farmers are trying to save their herds.

Livestock like cows, goats, sheep, pigs, and others are susceptible to the same types of heat-related illnesses as humans, including dehydration, heat exhaustion, and heat stroke. As temperatures have climbed in recent years, so too have their impacts on the country’s vast livestock populations. Last summer in Kansas, a heat wave killed over 2,000 cattle when temperatures hit 104 degrees Fahrenheit. This summer, hundreds of cattle have died in Iowa in late July because of extreme heat and humidity.

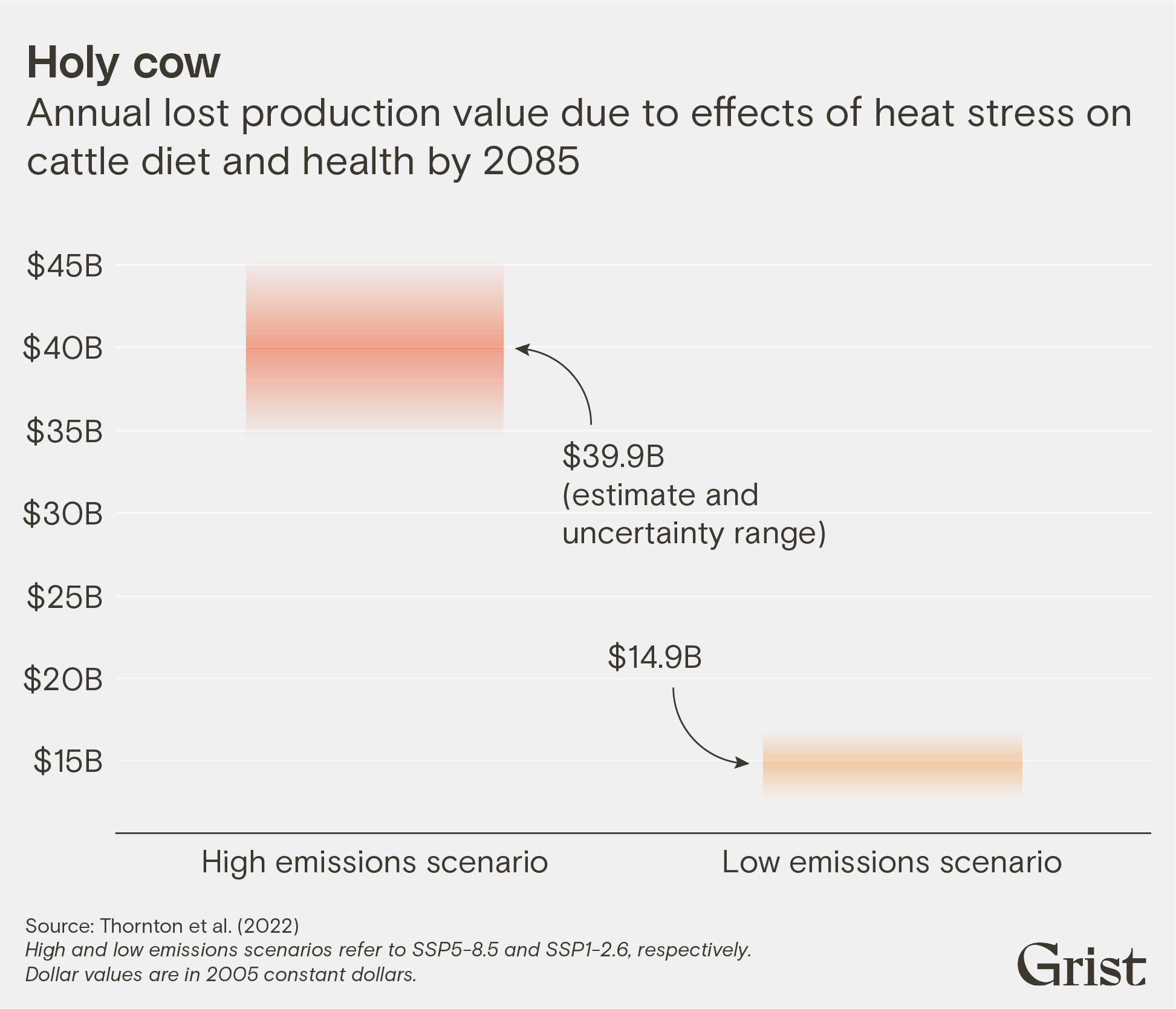

By mid-century, America’s heartland could form part of an “extreme heat belt” that stretches from Texas to Chicago, up the central United States, experiencing heat index conditions of 125 degrees F or more, according to the nonprofit climate research organization First Street Foundation. Scientists also estimate that losses from livestock heat-stress could reach almost $40 billion per year by the end of the century. Add worsening drought conditions and its impact on food availability, and livestock and the farms that own them have a difficult stretch ahead.

Farmers are now searching for solutions on how to keep their animals safe. One such method is something known as silvopasture, which incorporates trees — often harvestable fruit or nut trees — and grazing on the same land, Grist contributor John McCracken reports today.

Shade during extreme heat is crucial to keeping core body temperatures low enough to maintain vital systems. This is as true for livestock as it is for humans. For beef and dairy cows, of which there are 89.3 million in the U.S., ideal body temperatures range from 44 to 77 degrees F, according to the Department of Agriculture, or USDA. Above those, heat stress causes cattle to produce less milk and decreases their fertility.

In Missouri, farmer Josh Payne is introducing shade in the form of chestnut trees, planting 600 of them across the same fields his cattle graze. The trees are a long-term solution and will take time to reach their full shading potential, so in the meantime, Payne is using mobile shades to protect his animals. But he’s counting on the trees to protect his farm and animals in the long run — both from extreme heat and as a way to help counter climate change.

Silvopasture can improve soil health and increase a field’s uptake of carbon dioxide through photosynthesis. An estimate from the nonprofit climate solutions organization Project Drawdown predicts that the method could sequester five to 10 times more carbon dioxide than a pasture without trees.

A USDA survey from 2017 showed that only 1.5 percent of U.S. farmers practice any kind of agroecology, the ancient regenerative farming movement that includes silvopasture. In Illinois, the nonprofit Savanna Institute has been funding projects to help farmers better understand how to do silvopasture more effectively, and uses similar methods to Payne’s, notably planting chestnut trees.

As McCracken writes, “Planting trees in a field seems almost too simple as a way to keep livestock safe and healthy in a hotter world.” But researchers know better, he notes. Silvopasture is complicated, as it requires a delicate balance between planted trees, natural forests and brush, and livestock. But as farmers grapple with worsening extreme heat, it can be successful because of its flexibility.

“Silvopastures are not a silver bullet, but at this point, I don’t think we have any silver bullets anymore,” Ashley Conway-Anderson, a researcher at the University of Missouri Center for Agroforestry, told McCracken for Grist.

A recent study in the journal The Lancet examined the economic damage heat stress will have on cattle under various climate scenarios. The animals comprise a key part of the agricultural sector, accounting for 17 percent of industry revenues in 2022, according to the USDA.

Data Visualization by Clayton Aldern

A loneliness epidemic is causing heat waves to be more deadly: Americans are now more socially isolated than ever before, with only 3 in 10 people knowing their neighbors. In a crisis, though, neighbors and friends can be the first line of defense to help. As this summer’s record-breaking heat continues, my colleague Akielly Hu looks into how isolation and extreme heat are killing people, and some possible solutions that cities are taking to tackle the issue.

Arizona declares extreme heat emergency: Governor Katie Hobbs of Arizona declared a state of emergency on Friday, due to the state’s sky-high temperatures. In Phoenix, the city’s longest-lasting heat wave spanned the entire month of July. The declaration will free up funding from the state for cities and municipalities to tackle the issue of extreme heat, Jessica Boehm reported for Axios. Additionally, as my colleague Zoya Teirstein reported last week, extreme heat has inundated the city’s emergency rooms, with people experiencing burns from falling on the sidewalk, severe dehydration, and other heat-related illnesses

A long-lasting marine heat wave is endangering ocean ecosystems:

Starting in 2013, a phenomenon known as “the Blob” formed in the northern Pacific Ocean, with ocean temperatures increasing by 4 to 10 degrees F. It was the largest and longest marine heat wave on record and caused havoc for fisheries. Salmon, cod, crabs, and many other species declined as temperatures rose, causing billions of dollars in economic damage. As my Grist colleague Max Graham reports, marine heat waves such as the Blob are becoming more common and more severe, endangering not only marine life, but also the coastal communities reliant on fisheries for their livelihoods.

Extreme heat could threaten unborn children: Researchers have long known the serious toll that extreme heat can have on the human body, but until recently, two groups remained largely understudied: unborn children and pregnant people. New research finds connections between scorching temperatures and a slate of health concerns for these vulnerable populations, from preterm birth to low-birth weight to other conditions, like stillbirths. One study from 2022 found that for every 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees F) of warming, there was a 17 percent increase in fetal stress, usually an increased heart rate or decreased blood flow, Grace Browne reports for WIRED.

Does extreme heat spell the end of the European summer vacation?: Record-breaking heat in Europe this summer has been interfering with travelers’ plans, Ceylan Yeginsu reports for the New York Times. Yeginsu herself experienced 113 degree F temperatures when attempting to vacation in Turkey, and travelers in Italy and Greece have also faced scorching heat. This summer marks the latest in a few years of hotter summers for the continent, with last year’s heat wave killing an estimated 61,000 people, according to a study I reported on earlier this summer.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Protecting livestock from heat on Aug 15, 2023.

Having fresh, stain-free carpeting, area rugs, and furniture enhances the aesthetics of the room, creating…

The post Better Carpet and Upholstery Cleaners appeared first on Earth911.

Did you know that plastic bags account for 11.18% of plastic pollution? If you’re still…

The post We Earthlings: Plastic Bag Pollution appeared first on Earth911.

This story is part of Record High, a Grist series examining extreme heat and its impact on how — and where — we live.

Josh Payne planted chestnut trees six years ago. The rows of nut trees haven’t fully matured yet, but he’s banking on the future shade they’ll provide to shield his animals from sweltering heat.

“We started with that largely because we want to get out of commodity agriculture,” Payne said. “But also because I’m worried that in our area it’s getting hotter and drier.”

Payne operates a 300-acre regenerative farm in Concordia, Missouri, an hour outside of Kansas City, where he raises sheep and cattle. By planting 600 chestnut trees, he is bracing for a future of extreme heat by adapting an agriculture practice known as silvopasture. Rooted in preindustrial farming, the method involves intentionally incorporating trees on the same land used by grazing livestock, in a way that benefits both. Researchers and farmers say silvopastures help improve the health of the soil by protecting it from wind and water, while encouraging an increase of nutrient-rich organic matter, like cow manure, onto the land.

It also provides much-needed natural shade for livestock. According to the First Street Foundation, a nonprofit climate change research group, chunks of America’s heartland — including Kansas, Iowa, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and Missouri — could experience at least one day with temperatures of 125 degrees Fahrenheit or hotter by 2053.

When temperatures rise above 80 degrees, the heat begins to take a toll on animals, which will try to cool themselves down by sweating, panting, and seeking shelter. If they are unable to lower their body temperature, the animals will breathe harder, becoming increasingly fatigued, and eventually die.

Research shows that as the planet warms, livestock deaths will increase. Last year, when temperatures exceeded 100 degrees in southwestern Kansas, roughly 2,000 cattle in the state died; the Kansas Livestock Association estimated each cow to be worth $2,000 if they were market-ready, equaling an economic loss of $4 million. And so far this year, the trend is continuing, with livestock producers in Iowa already reporting hundreds of cattle deaths in the latter half of July alone.

According to the United States Department of Agriculture, or USDA, the ideal temperature for beef and dairy cows ranges between 44 and 77 degrees. Above those temperatures, heat stress causes cattle to produce less milk and decreases their fertility.

Payne’s family farm is a microcosm of American agriculture’s monocrop past and its changing future. He inherited the land from his grandfather, who spent decades tearing trees out of the ground in favor of growing corn and soybeans, using chemical fertilizers for years. His family was hardly alone in doing so: Along with cattle, corn and soybeans make up the top three farm products in the U.S., according to the industry group American Farm Bureau.

Missouri produced nearly $94 billion of agricultural products last year — an economic driver under threat from climate change, which has brought more intense floods and droughts to the state. Last year, the Mississippi River, which flows through Missouri, reached severely low water levels in the face of a historic drought, stopping the barge travel that supports the country’s agricultural economy. When Payne spoke to Grist in July, he was hoping for rain to come soon amid the humid 98-degree heat.

To prevent harm to his 600 sheep and 25 cattle, Payne currently uses portable structures to provide artificial shade while he waits for his chestnut trees to mature. This technology acts like a big umbrella that can be moved as a herd moves, but it doesn’t protect animals from reflected heat and sun rays from the sides the same way a tree canopy can.

In addition to the shade his future nut trees will provide, they’ll be a source of income, too. Payne said it’s likely he’ll make more money on 30 acres of chestnut trees than he would on 300 acres of row crops like corn.

“We’re rethinking the farm process based on climate predictions,” Payne said. “Here we are planting trees in our pastures, so that in 10 to twelve years we can have dappled shade.”

Planting trees in a field seems almost too simple as a way to keep livestock safe and healthy in a hotter world. But Ashley Conway-Anderson, a researcher at the University of Missouri Center for Agroforestry, knows better. She said of all the USDA’s land management systems used to blend forest and livestock, silvopasture is the most complicated, as it requires a delicate balance between planted trees, natural forests and brush, and livestock.

But she will admit the practice is common sense.

“Trees provide shade. That’s the place where you want to be when it’s hot, right?” Conway-Anderson said. “The idea behind a well-managed silvopasture is your taking that shade and dispersing it across the field.”

Conway-Anderson said farmers are adapting their land to silvopastures at a time when agriculture as a whole is wrestling with its role in climate change. The sector accounts for roughly 11 percent of the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions, according to the USDA.

In addition to mitigating extreme heat risks and promoting soil health, trees planted on pastures and fields act as a way to sequester carbon out of the atmosphere through the process of photosynthesis. Project Drawdown, a nonprofit known for its expansive list of practices to prevent further climate harm, estimates that silvopastures could sequester five to 10 times the amount of carbon than a treeless pasture of the same size.

Notably, however, while carbon accounts for the main source of human-caused greenhouse gasses, agriculture’s role in a warming planet largely comes from methane produced by livestock and their waste. But silvopastures help combat that — animals that move around to graze end up trampling on their waste, working it into the soil where it’s repurposed as a natural fertilizer; in contrast, most farm operations pool all livestock waste together in large ponds from which a concentration of methane is then emitted.

Conway-Anderson said agroforestry and silvopastures aren’t always a one-size-fits-all solution. She said farmers are having to “get big or get out,” and aren’t always able to invest the time or money in planting trees or revitalizing woodland they might already own.

“We’ve created an economic system where we have incentivized and subsided specific crops, products, and ways of doing farming and agriculture that has really sucked the air out of the room for smaller, diversified operations,” she said.

On the other hand, she said silvopasture practices can be successful because of their flexibility. Farmers can use trees they already own. They can graze goats, pigs, sheep, cattle, and more under the shade of nut trees, fruit trees, and trees whose trimmings and branches can be harvested and sold to the lumber industry.

“Silvopastures are not a silver bullet,” Conway-Anderson said. “But at this point, I don’t think we have any silver bullets anymore.”

At Hidden Blossom Farms in Union, Connecticut, a rural town located near the border of Massachusetts, Joe Orefice has been methodical in his implementation of silvopasture.

Orefice, a Yale School of the Environment professor of agroforestry, raises tunnel-grown vegetables, figs, and roughly two dozen grass-fed cows that enjoy the shade of apple trees on a 134-acre farm. He said there are currently only two acres of fruit trees the cattle use for cover.

Despite the small acreage, Orefice said, he has focused primarily on soil health, a key aspect of silvopasture management. Without properly maintained grasses and soil, trees won’t grow, and there wouldn’t be any shade for his cattle.

“You need to manage the grasses so young trees will grow,” he said.

In addition to land management and soil health, Orefice said the animal welfare benefits of shade were top of mind.

“I don’t want to eat a big meal if I’m sitting in the sun on a hot and humid day, and we want our cattle to eat big meals because that’s how they grow or keep their calves healthy by producing milk,” he said.

Orefice said a common misconception about silvopasture leads to farmers just taking livestock they own and putting them in the forest without any additional management. He said this can damage soil when livestock, especially pigs, aren’t routinely moved. While it might seem counterintuitive, he said one of the first steps of creating a proper silvopasture from an existing forest is to trim trees and till the soil.

While he only raises 25 beef cattle, Orefice said he’s seen larger farms begin to implement silvopasture practices. He said raising tree crops, like nuts or figs and other fruits, is a boon for farmers who switch to more diversified crop operations versus large, concentrated animal-feeding operations.

For example, Orefice noted that if farmers in the Corn Belt, who are facing continued droughts and an extreme heat future, switched to tree crops, the upfront costs might be expensive and hard. Still, they would eventually make more money on tree crops than on corn or soybeans. The problem, as he sees it, is there is no incentive or safety net for farmers to begin to adopt these practices at the same rate as they have mainstream ones.

“The question isn’t really, ‘Is silvopasture scalable?’” Orefice said. “The question is, ‘Does our economy allow us to scale pasture-based livestock production?’”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Livestock are dying in the heat. This little-known farming method offers a solution. on Aug 15, 2023.