Today’s quote is from Senator Gaylord Nelson, co-founder of Earth Day: “The ultimate test of…

The post Earth911 Inspiration: For Future Generations appeared first on Earth911.

Today’s quote is from Senator Gaylord Nelson, co-founder of Earth Day: “The ultimate test of…

The post Earth911 Inspiration: For Future Generations appeared first on Earth911.

Activists pushing San Diego to take over the city’s investor-owned utility aren’t letting last year’s defeat of a similar effort in Maine deter their goal of establishing a nonprofit power company. They recently submitted petitions bearing more than 30,000 signatures from residents who want the City Council to let voters decide the matter this fall.

Advocates say a municipal takeover of San Diego Gas & Electric would deliver cheaper rates and a faster, more affordable, and more equitable transition to clean energy. Still, the measure faces long odds from skeptical council members who have twice rejected similar proposals.

The campaign is the first public power ballot initiative since 70 percent of voters in Maine rejected a proposal to take over the state’s two largest utilities. A group called Power San Diego delivered several cardboard boxes filled with petitions to the San Diego city registrar’s office on May 14. If just over 24,000 of the signatures on those documents are deemed valid, the Council will have to decide whether to put the question to voters in the next election.

What’s happening in Southern California reflects growing frustration with the high rates and lackluster service investor-owned utilities often provide — and a desire to accelerate the green transition. Similar campaigns are afoot in Rochester, New York and San Francisco, and Empire State lawmakers recently introduced a bill to buy out Central Hudson Gas & Electric and create a public power authority.

“Across the country, people are talking about public ownership of energy,” Sarahana Shrestha, a New York state assembly member who co-sponsored the bill, told Grist. “If we want a just transition — taking care of workers, and making sure that it’s affordable and brings benefits back into communities — there’s no effective way of doing that while you’re still answering to shareholders.”

San Diego residents pay some of the nation’s highest electricity rates, and by one estimate, more than a quarter of customers are behind on their payments. (The utility has attributed its high rates to the cost of everything from wildfire prevention to building transmission lines and other clean energy infrastructure.) Takeover advocates say the move would save residents 20 percent on their utility bills because a nonprofit model eliminates the need to provide shareholders with a return. It estimates the cost at $3.5 billion, citing a study commissioned by the city last year.

That analysis found that the utility’s 700,000 customers who live within the city of San Diego could save 13 to 14 percent annually if the city bought the utility’s grid assets for $2 billion and created a municipal utility. The math is less favorable if the cost of the buyout goes up, however; at a price of $6 billion, ratepayers could face additional costs of $60 million over the first decade but see long-term savings after 20 years.

San Diego Gas & Electric vehemently opposes the effort and has backed the political action committee Responsible Energy San Diego to block it. The organization calls itself “a coalition of diverse San Diego leaders” fighting “a reckless ballot initiative to force a government takeover of the energy grid.” The utility has contributed well over $700,000 to the committee, according to records on the San Diego Ethics Commission website.

That’s more than twice what Power San Diego has raised and reflects a dynamic in which political action committees supported by Maine’s two investor-owned utilities received 34 times more money than public power advocates. Activists there say that allowed the utilities to finance a robust campaign of advertising and misinformation to defeat the referendum.

San Diego Gas & Electric has hired Concentric Energy Advisors, the same consultants who helped defeat the effort in Maine. The company’s study commissioned by the San Diego utility estimated the cost of a public takeover of the grid at $9.3 billion.

Matt Awbrey of Responsible Energy San Diego told Grist the city should address other priorities like affordable housing rather than a proposal “to create a new government-run utility that has no plan, budget, or verifiable cost estimates.” He said the cost of the takeover likely would bring “higher taxes, higher electric bills, and/or cuts to essential city services we all depend on.”

Power San Diego intended to gather 80,000 signatures by July, which would have placed the proposal on November’s ballot. But it lacked the funding for such an effort and decided to seek 30,000 signatures, or roughly 3 percent of registered voters. That would require the City Council to vote on whether to put the matter to voters.

Dorrie Bruggeman, senior campaign coordinator for Power San Diego, doesn’t expect the council to do that; it already has rejected such a proposal on two occasions, with council members calling for greater detail on costs and projected revenues. Council President Sean Elo-Rivera is among those with reservations.

“I have no love for corporate monopolies reaching into the pockets of everyday working people,” he told the local news outlet La Jolla Light. “But this is a very complex and important issue and I don’t think this is baked enough to go to the voters.”

Regardless of any qualms the council may have, Bill Powers, chair of Power San Diego, said his organization has prompted an important discussion within the community and sparked voter engagement on the issue. The next step is getting policymakers behind the idea.

“If we can get a couple of council members that are open to public power, if we can get a mayor who is open to public power, which we’ve had in the past, then the movement isn’t dependent on the endpoint of a ballot initiative,” Powers said.

Such campaigns are gaining momentum elsewhere. Public power advocates in Rochester, New York, want the city to evaluate the costs and benefits of a municipal utility. In San Francisco, city officials are currently working with the California Public Utilities Commission to determine how to set a fair price for Pacific Gas & Electric’s distribution grid, in the hopes of creating a citywide public power system.

On May 17, New York Assemblymember Shrestha and State Senator Michelle Hinchey introduced a bill to create the Hudson Valley Power Authority, a public power entity that would buy out Central Hudson Gas & Electric. The utility has drawn criticism for its high rates and a string of billing failures since 2021. If the measure passes, the Hudson Valley Power Authority would seek to lower rates, improve service, and hasten the green transition while protecting labor rights.

Joe Jenkins, Central Hudson’s director of media relations, told Grist the proposed takeover would involve “significant hidden costs, loss of jobs, and loss of tax revenue for towns and schools,” adding that rates for municipal utilities in New York are nearly 9 percent more expensive than those of investor-owned utilities.

Shrestha said the legislation reflects her constituents’ growing interest in public power. Her office has hosted seven town halls this past year to discuss energy democracy. “People are so fed up with getting bills that are inconsistent and late,” she said. “People are really excited about learning how we can actually get public power done.”

Correction: This story misstated the number of customers who could save 13 to 14 percent annually if the city bought the utility’s grid assets.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline San Diego ponders a bid to take over its for-profit energy utility on May 31, 2024.

International climate negotiations have long been haunted by a broken promise. In the wake of collapsed negotiations at the United Nations climate conference in Copenhagen in 2009, wealthy nations, led by the United States, pledged to provide developing countries with $100 billion in climate-related aid annually by 2020. The money was meant in part to ease tensions between the rich countries that had contributed the most to climate change historically and the poorer nations that disproportionately suffer the effects of a warming planet. But rich countries fell short of the target in both 2020 and 2021, deepening mistrust and stymying progress during the annual United Nations climate conferences, which are known by the abbreviation COP.

A new report from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, or OECD, confirms what the international organization began to suspect just before last year’s COP28: that wealthy nations finally surpassed the $100 billion goal in 2022. And while they were two years late delivering on their promise, rich countries partially compensated for their earlier shortfalls, contributing nearly $116 billion in climate aid to developing countries in 2022, according to the latest data available. That additional funding helps fill the roughly $27 billion gap resulting from rich countries’ failure to meet the $100 billion threshold in each of the two years prior.

“If you underachieved in the first two years, overachieving in the rest of the period is a good way to make up for that, to make amends,” said Joe Thwaites, a climate finance expert at the Natural Resources Defense Council, a U.S.-based environmental nonprofit.

Even $100 billion, however, is far lower than the developing world’s estimated need. United Nations-backed research projects that developing countries (excluding China) will need an eye-popping $2.4 trillion per year by 2030 to transition away from fossil fuels and adapt to climate change.

Serious questions also remain about the quality and accounting of the existing funding. According to the OECD report, more than two-thirds of the public finance in 2022 was provided in the form of loans rather than no-strings-attached grants. That means developing countries are required to pay the money back, often with interest at market rates. A recent Reuters investigation also found that some aid providers required recipients to work with companies based in donor countries, meaning that much of the aid money ultimately found its way back to wealthy nations.

Such findings are likely to inform talks next week, as climate negotiators meet in Bonn, Germany, in preparation for COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, at the end of the year. Negotiators need to agree on a new collective goal for climate aid to developing countries this year. So far, different countries have submitted a range of proposals, with some nations floating $1 trillion annually as an appropriate number. Wealthy countries also want to expand their ranks so that some relatively rich countries that are technically classified as “developing,” like the oil-rich states of the Persian Gulf, can contribute funds toward the goal. Historically, only countries that the United Nations designated as “developed” in the 1990s have been on the hook.

The new OECD report’s findings may be advantageous to wealthy nations as they negotiate these thorny issues, according to Thwaites. “Developed countries were not necessarily arguing from a position of strength or moral high ground, having failed to meet the $100 billion on time,” he said. If countries continue to provide a similar level of funding for the next few years, they could make up for the shortfall. “Making up for 2020 and 2021, meeting the goal in those two years, could help rebuild a bit of trust,” Thwaites added.

The OECD report found that funding from all types of sources — multilateral development banks, the private sector, and public finance from governments — grew across the board in 2022. The increase in private-sector funding was particularly notable, jumping by more than 50 percent to a total of $21.9 billion.

The report indicated specific progress on funding for adaptation measures like sea walls and disaster-resilient infrastructure, an oft-overlooked area of climate finance. In 2021, countries pledged to double adaptation finance from the $19 billion provided in 2019 to $38 billion by 2025. According to the OECD report, adaptation funding had already risen to $32.4 billion one year after the pledge.

As in past years, loans continued to make up the majority of funding. While developing countries have called on wealthy nations to move away from loans as the primary form of aid, all parties seem to agree that loans can be appropriate in some circumstances. For projects that generate revenue — such as investments in renewable energy — loans tend not to have a detrimental effect because they pay for themselves. But for measures that don’t generate revenue — in particular, adaptation measures like sea walls — loans can trap countries in cycles of debt. As a result, the call for increasing grant-based funding has grown louder in recent years.

“A lot of countries are in debt distress,” said Thwaites. “And if they take on more loans for adaptation, where it doesn’t necessarily generate a return on the investment, that’s a challenge.”

Editor’s note: The Natural Resources Defense Council is an advertiser with Grist. Advertisers have no role in Grist’s editorial decisions.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Better late than never: Wealthy nations finally meet $100 billion climate aid goal on May 31, 2024.

Georgia Governor Brian Kemp called for more new nuclear energy at an event Wednesday celebrating the first new nuclear reactors built in the U.S. in decades, at Plant Vogtle near Augusta, Georgia. The construction of those reactors, known as Vogtle Units 3 and 4, cost more than twice its original budget and ended years behind schedule.

“Today, we celebrate the end of that project,” Kemp told the crowd of state officials and utility executives. “And now, let’s start planning for Vogtle Five.”

That could be a tough sell to Georgians who have seen their bills go up multiple times to pay for the new reactors and for shareholders of the power plant’s largest owner, who had to absorb some of the costs. Originally billed as the dawn of a new nuclear era and priced at $14 billion, the Plant Vogtle project was plagued by repeated delays and ultimately cost an estimated total of more than $31 billion.

When lead contractor Westinghouse filed for bankruptcy in 2017, prompting South Carolina to abandon its own nuclear project, Vogtle became the only new nuclear construction in the country. It still is.

“If building more nuclear were a good idea, other states would be jumping on the bandwagon now,” said Liz Coyle, executive director of the consumer advocacy group Georgia Watch. “The fact that they’re not, I think, speaks volumes.”

Coyle said her group is preparing to fight any proposal for another reactor.

For their part, the elected officials and utility executives at Wednesday’s event spoke of Plant Vogtle as a success story.

“Vogtle 3 and 4 don’t just represent an incredible economic development asset for our state and … a milestone for our entire country,” Kemp said. “They also stand as physical examples of something that I remind myself of every day: Tough times don’t last. Tough people do.”

Triumphal arrangements of the national anthem, “God Bless America,” and “Georgia On My Mind” backed by a gospel choir bookended the celebratory speeches. Attendees could snack on a sheet cake model of the power plant rendered in fondant.

Speakers touted Plant Vogtle as a win for clean energy, since it can produce enough electricity to power a million homes and businesses without the greenhouse gas emissions produced by coal or gas, according to Georgia Power, which owns the largest stake in the new reactors. That carbon-free energy is key to attracting new businesses to the state, Kemp and others said.

All five members of the Georgia Public Service Commission, or PSC — which oversees Georgia Power’s planning and rates, including the Vogtle project — addressed the crowd.

“I just hope that we keep it up. We really should,” said commissioner Tricia Pridemore. “If we want to continue clean energy for our nation, it’s gonna take more than four.”

In December, the PSC approved a deal that hikes Georgia Power customers’ rates now that Vogtle Unit 4 is online.

After the Wednesday event, commissioner Tim Echols said he supports more nuclear power in Georgia, but said a further Vogtle expansion would need to come with protections against runaway costs and other problems that plagued the last project.

“I really need some protection against a bankruptcy,” he said. “I just can’t do it on the same basis again.”

Echols suggested a federal “backstop” and a mechanism to ensure large customers like factories and data centers would pay for the bulk of nuclear construction.

Under current Georgia law, a further expansion of Plant Vogtle would need to be financed differently than the project that just wrapped up, Coyle said. In 2018, state lawmakers approved a sunset provision for the state law that had allowed Georgia Power to pass Vogtle’s financing costs on to customers during construction. Barring another change, that would mean Southern Company and its shareholders would shoulder those costs.

Coyle said she’ll be urging lawmakers to keep it that way.

“Georgians are struggling, really, really struggling already to pay their power bills,” she said. “I hope we don’t have to go down this path again.”

On Friday, U.S. Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm and national climate advisor Ali Zaidi are visiting Vogtle for another event at the power plant. According to the Department of Energy, they plan to meet with local officials, as well as industry and labor leaders.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Georgia governor calls for even more nuclear power despite budget woes on May 31, 2024.

Crows are highly intelligent, social birds found on every continent other than South America and Antarctica.

In a new study, researchers from the Institute of Neurobiology at Germany’s University of Tübingen have found that crows are able to learn to produce a specific number of calls, showing advance planning.

How many calls they will make can be predicted from the first vocalization in a sequence, a press release from University of Tübingen said.

“Producing a specific number of vocalizations with purpose requires a sophisticated combination of numerical abilities and vocal control,” the researchers wrote in the study. “We show that crows can flexibly produce variable numbers of one to four vocalizations in response to arbitrary cues associated with numerical values. The acoustic features of the first vocalization of a sequence were predictive of the total number of vocalizations, indicating a planning process. Moreover, the acoustic features of vocal units predicted their order in the sequence and could be used to read out counting errors during vocal production.”

Carrion crows are known for their impressive learning ability, which includes being able to count.

“In addition, they have very good vocal control. They can control precisely whether they want to emit a call or not,” said Andreas Nieder, a professor of animal physiology at University of Tübingen, in the press release.

The research team conducted behavioral experiments to see if three carrion crows could combine their ability to count with vocal control.

The corvids were given the task of producing from one to four calls that appropriately corresponded with specific sounds or an array of Arabic numerals, followed by pecking an enter key.

“All three birds succeeded in this. They were able to count their calls in sequence,” Nieder said in the press release.

The crows displayed a relatively long response time between when they were presented with the stimulus and their first call, which became longer as more calls were added. The delay’s length was not affected by the type of stimulus.

“This indicates that, from the information presented to them, the crows form an abstract numerical concept which they use to plan their vocalizations before emitting the calls,” Nieder explained. “Using the acoustic properties of the first call in a numerical sequence we could predict how many calls the crow would make.”

Some errors were detected in the birds’ calls.

“Counting errors, such as one call too many or one too few, arose through the bird losing track of the calls already made or still to be produced,” Nieder said. “We are also able to read out these types of errors from the acoustic properties of the individual calls.”

Being able to produce a deliberately chosen number of calls requires a sophisticated combination of vocal control and numerical competence.

“Our results show that humans are not the only ones who can do this. In principle it also opens up sophisticated communication to the crows,” Nieder said.

The study, “Crows ‘count’ the number of self-generated vocalizations,” was published in the journal Science.

The post Highly Intelligent Crows Can Plan How Many Calls to Make, Study Shows appeared first on EcoWatch.

A new report by scientists at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and renewables consulting firm Clean Kilowatts has found that the United States’ increasing use of renewable energy has improved air quality and reduced the country’s greenhouse gas emissions while producing monetary benefits in the hundreds of billions of dollars.

For the data-based study, the research team focused on a surge in U.S. renewable energy use from 2019 to 2022, reported The Guardian.

“From 2019 through 2022, wind and solar generation increased by about 55%,” said Dev Millstein, lead author of the study and a research scientist with Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, as The Guardian reported. “By 2022, wind and solar provided roughly 14% of total electricity needs for the U.S.”

The researchers found that the country’s reduction in the use of fossil fuels, coupled with an increase in wind and solar, slashed its carbon emissions by 992.1 million tons — equal to taking 71 million automobiles off the road each year.

“Wind and solar generation reduce electric sector pollutant emissions and associated climate-related and air quality-related health damages,” the scientists wrote in the study. “From 2019 through 2022, wind and solar generation in the United States provided $249 billion dollars of climate and air quality benefits based on central estimates. In 2022, the normalized benefits were $143/MWh and $100/MWh for wind and solar, respectively, or $36/MWh and $17/MWh when only including air quality benefits. Combined, wind and solar generation led to 1,200 to 1,600 fewer premature mortalities in 2022.”

Air quality benefits from the use of renewables can eclipse major climate benefits, the researchers wrote. In order to bring the co-benefits to light, they quantified the amount of toxic air emissions reductions that were provided by wind and solar, with a specific focus on the fossil fuels nitrogen dioxide (NOx) and sulfur dioxide (SO2), reported The Guardian.

The team discovered that NOx and SO2 emissions — both associated with an increased risk of asthma and other health issues — had been reduced by 1.1 million tons during the study period.

To find out how much the reduction impacted public health, Millstein said they tracked the portion of the population that had been exposed to power plant pollution using air quality models. They also looked at disease research to determine emissions impacts and quantify the value of reducing the population’s risk of early death using a dollar value established by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The researchers also looked at the advantages of wind and solar in specific regions of the U.S. They found wind to be especially beneficial in Central states because of the displaced emissions on local power grids. The same was true of solar in the Carolinas.

“These findings can help us target future wind and solar development to provide the greatest climate and health benefits,” said Jeremiah Johnson, a North Carolina State University professor of climate and energy who was cited in the study, as The Guardian reported.

Johnson hopes the research will help people pay attention to the benefits renewables are already providing.

The public “is often focused on the challenges we face” as far as ecological damage goes, Johnson said. “But it is also important to recognize when something is working.”

The post Increasing Renewable Energy Use in the U.S. Brings Billions in Benefits, Study Finds appeared first on EcoWatch.

With all eight native freshwater turtle species of Ontario considered at-risk, researchers have created protective nests to help boost offspring survival.

Researchers at the University of Waterloo and McMaster University designed a nest with materials like moss and lichen to mimic the turtles’ natural rocky nesting sites. As the research team pointed out in their study, published in the journal Restoration Ecology, previous nest restoration efforts often focused on building nests from materials like sand and gravel.

Examples of nest sites created with moss (A), mixed materials (B) and lichen (C). Restoration Ecology

The team instead focused on designing a nest that would work best for rocky landscapes, where freshwater turtles often create their nests in the cracks of rocks. Plus, they pointed out in their study that the mound nests made with sand and gravel tend to require regular upkeep to prevent plants from growing too densely into the nesting areas.

The researchers created the first nest for a research site at Georgian Bay in 2019 and monitored it for five years. During this time, the researchers didn’t need to make any repairs or adjustments to the nest they created, meaning it could be a low-maintenance way to help with freshwater turtle protection efforts.

A Blanding’s turtle at its new nesting site. Hope Freeman / McMaster University

While freshwater turtles can make their own nests, these efforts are often set back as the animals face threats from habitat destruction.

“The number 1 threat to freshwater turtles in Ontario is habitat loss and degradation from urbanization,” Chantel Markle, the lead author of the study and professor in the Faculty of Environment at the University of Waterloo, said in a press release. “Georgian Bay is one of the last remaining strongholds for some at-risk turtles in Ontario, so this new design is a step towards the survival of the species.”

Additionally, freshwater turtle eggs depend on certain temperatures to produce male or female hatchlings, and too many males or females can limit the reproduction of offspring in future generations, further threatening the survival of at-risk species. So the researchers took extra care to create warm, well-draining nests that would give the offspring the best odds of survival as well as hopefully improving population size in the long-term.

“Taking an interdisciplinary approach to assessing the success of habitat created for animal reproduction is critical,” Markle said. “In this study we evaluated the physical, ecohydrological and ecological success of the created nesting habitat — a combination not often seen in a single study.”

The team found that the eggs were 41% likely to hatch in the human-crafted nests, while the natural nesting sites only had a 10% chance for eggs to hatch.

Next, the researchers plan to scale the nest design to apply to other local, rocky landscapes. Additionally, they made their nest creation process available in the published study to aid turtle conservationists in other areas throughout Canada and the U.S.

The post Researchers Develop Protective Nests for At-Risk Turtles in Ontario appeared first on EcoWatch.

International climate change panels often point out that women are more vulnerable to climate change than men. Hotter temperatures and more volatile weather inflame existing gender-based vulnerabilities, like domestic violence, inadequate access to health care, and financial insecurity. But there is another, largely invisible layer of climate impacts that falls along gendered lines: Research shows that climate change takes a profound physical toll on bodies that can bear children — from menstruation to conception to birth.

There are various pathways by which climate change worsens health problems before, during, and after pregnancy. A pregnant person’s immune system stands down during those crucial nine months so as not to reject the growing fetus, leaving the gestating parent more susceptible to climate-driven infectious diseases like malaria. Exposure to extreme heat during pregnancy increases the likelihood of preterm birth, although the biological mechanism behind this relationship is still poorly understood. Sea level rise infuses drinking water with salt, which can lead to high blood pressure — a risk factor during pregnancy for premature birth and miscarriage. And for those who have access to fertility treatment, which involves highly time-sensitive procedures, increasingly massive and intense storms are making assisted conception unpredictable.

Women in Bangladesh are confronting the dangerous health effects of consuming salty water. They won’t be the last.

A couple spent years and tens of thousands of dollars trying to have a baby. Then Hurricane Ian hit.

Heat waves are making pregnancy more dangerous and exacerbating existing maternal health disparities.

After years of neglecting to study the climate-related health conditions that affect women and gender minorities who can get pregnant, the medical establishment is just beginning to understand the scope of these threats. At a moment when reproductive autonomy is under political attack, climate change is making it even more dangerous to have a uterus.

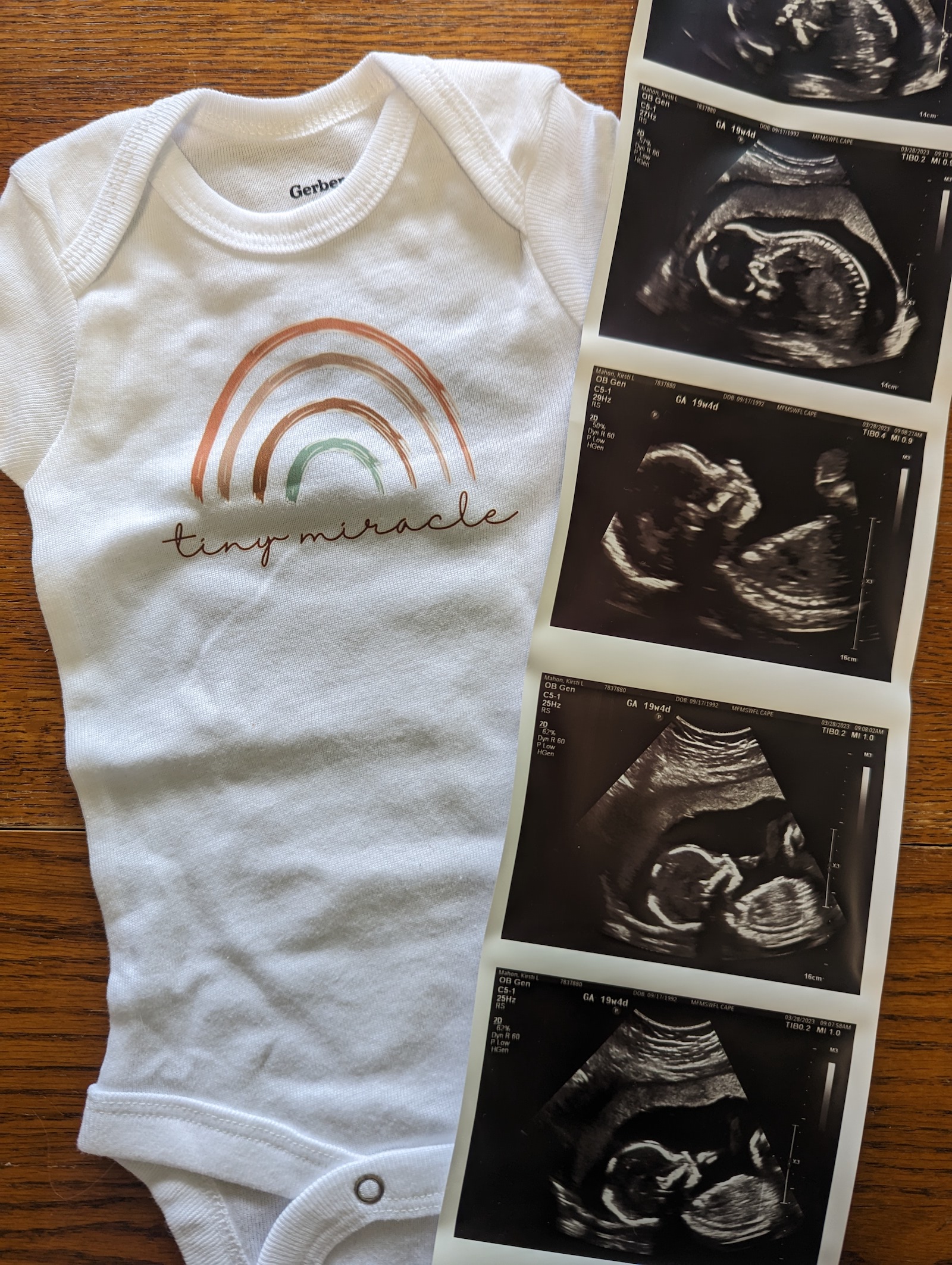

Here, you’ll find a package of stories that will help you understand a few of the profound effects warming has on people who can get pregnant. The full range of climate-related reproductive threats is vast, and this series doesn’t touch on all of them. Instead, it provides a series of snapshots — four windows into the lives of women who are facing unexpected risks as they attempt to conceive, gestate, and give birth to children in a warmer world. Their stories are a warning to us all. —Zoya Teirstein

WRITERS | Zoya Teirstein, Virginia Gewin, Jessica Kutz, Mahadi Al Hasnat

STORY EDITORS | L.V. Anderson, Paige Vega, Kara Platoni

MANAGING EDITOR | Jaime Buerger

ART DIRECTION | Teresa Chin

ILLUSTRATIONS | Amelia K. Bates

DATA VISUALIZATION | Clayton Aldern, Jasmine Mithani

COPY EDITORS | Claire Thompson, Joseph Winters, Kate Yoder

FACT CHECKERS | Sarah Schweppe, Melissa Hirsch, Caity PenzeyMoog

PARTNERSHIP MANAGERS | Rachel Glickhouse, Abby Johnston, Megan Kearney

AUDIENCE + ENGAGEMENT | Myrka Moreno, Justin Ray, Shira Tarlo

DESIGN + DEVELOPMENT | Mia Torres, Jason Castro, Mignon Khargie

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Expecting worse: Giving birth on a planet in crisis on May 30, 2024.

On their very first date, Kirsti and Justin Mahon talked about wanting kids. They met on a dating app in 2016, nine months after Kirsti moved from Texas to Florida. Almost immediately, they fell in love.

A little over two years later, they got married. Six months after that, they started trying for a baby. To their surprise, they got pregnant right away. But just as quickly, they had an early miscarriage. At 27, Kirsti didn’t have any reason to suspect fertility problems, and her obstetrician was quick to reassure her: Kirsti’s blood work looked normal, and getting pregnant after a month of trying is a good sign of fertility. Conceiving again, she was told, would be easy.

Over the next two years, Kirsti got pregnant three more times. None of her pregnancies lasted beyond the first trimester.

“It felt like we were hitting a brick wall,” Kirsti said. In January 2022, the couple went to see a fertility specialist who conducted a series of intensive tests that uncovered what was really going on. Kirsti was only 29 years old at the time, but the specialist told her that her egg quality was that of a 40-year-old’s. In vitro fertilization, or IVF, the specialist said, was Kirsti and Justin’s best hope.

It didn’t take the couple long to decide to take the plunge. “With every loss that we had it was like I was watching Kirsti lose a piece of herself,” said Justin. “It became obvious with the consultation that the IVF process was really the only way to guarantee that this really brutal cycle wouldn’t continue.”

So they drained their savings, cashed in an old retirement account, and took out two loans to pay for the treatment. They live in Florida, a state where coverage isn’t mandated, so most of the procedures would be out of pocket. Justin estimates it cost between $25,000 and $30,000. The couple hammered out the minutiae of IVF with their specialist, down to the timing of every hormone shot. They felt ready.

But Kirsti and Justin hadn’t accounted for hurricane season.

If the process of getting pregnant naturally feels murky and unpredictable, in vitro fertilization turns conception into a science — every menstrual phase, reproductive hormone and embryo carefully screened, tested, and optimized. First, patients inject themselves with fertility hormones aimed at stimulating ovarian follicles and bringing as many eggs as possible to maturity. An IVF cycle can fail right then and there, with the bad news showing up on an ultrasound screen or on the printed pages of a laboratory test before the eggs are even collected. Often, too few follicles develop. Ovulation can happen prematurely, or the ovaries can become hyperstimulated, causing pain, nausea, or more serious health problems. Everything can go wrong, and everything — down to the timing of each hormone shot — needs to go right.

If it does, the patient’s eggs are removed for fertilization in an outpatient procedure called an egg retrieval. The eggs must be harvested 34 to 36 hours after the “trigger shot,” a final hormone injection which prompts the eggs to finish maturing, but before the ovary releases them into the fallopian tubes. Patients are administered a painkiller, then the doctor guides a needle through the vagina or stomach and into the ovaries, aiming to suction all the eggs from their follicles. Mature eggs — there can be dozens, just one, or none at all — are fertilized with sperm in vitro, Latin for “in the glass,” or in this case in a petri dish. There, the embryos mature for three to six days. Not all of them survive, or develop correctly. The ones that make it can be reinserted into the uterus right away or, more commonly, frozen for later use.

Two time-sensitive procedures bookend the most stressful and critical weeks of the IVF process. The first is the egg retrieval. Once the trigger shot has been administered, there’s no turning back. If the procedure doesn’t take place approximately 36 hours after the injection, the patient’s follicles rupture, casting the precious eggs irretrievably into the fallopian tubes. A missed alarm, a traffic jam, or a delayed flight can wreck an enormous financial and emotional investment.

The second is the embryo transfer. A patient’s uterine lining must be sufficiently thick when an embryo is reinserted — otherwise, the embryo won’t implant, and the patient won’t get pregnant. Doctors often prescribe additional hormone injections for up to 12 weeks to boost estrogen levels and thicken the uterine lining before a frozen embryo is thawed and transferred. Fertility clinics typically require patients to come in regularly for ultrasounds to determine the optimal day for the transfer. If the lining remains too thin, or if the patient’s menstrual cycle advances too far, then the transfer must be delayed for at least another month.

These windows of opportunity are narrow, and it doesn’t take much to slam them shut. For a growing number of would-be parents living in the coastal areas of the United States, where climate change is making hurricanes faster-moving and more intense, all it takes is a single storm.

In September 2022, the Mahons were preparing for the final stage of IVF: the embryo transfer.

Kirsti had already undergone the grueling egg stimulation and retrieval process, which produced 23 eggs. Four had turned into embryos, and three were genetically tested. Two came back healthy and had been frozen.

Her transfer had initially been scheduled for August, but it got canceled when Kirsti contracted COVID-19 that July. Now, as summer turned to fall, Kirsti spent five weeks injecting herself with hormones at their home on the outskirts of Naples, Florida, where she worked as an animal supervisor at the area zoo. Naples sits on Florida’s Gulf Coast, about 40 miles north of the northern edge of the Everglades.

Less than a week out from her transfer, she was at the clinic for a final ultrasound and some blood work when she asked whether she should be worried about a coming storm she had seen on a weather forecast. She remembers the nurse telling her, “We’ll keep an eye on it, but I really wouldn’t worry about it.” At that time, the storm system still looked like it might miss Naples.

By the weekend, though, what had started out as a tropical depression whipped itself into Hurricane Ian, which would turn out to be one of the deadliest and most destructive in U.S. history.

That Monday, Kirsti and her husband had grown increasingly worried, so they emailed the fertility clinic for an update. While they waited to hear back, they tracked Hurricane Ian on the news, watching as it made its way toward the U.S. “It just kept getting scarier and scarier,” Kirsti said.

On Tuesday, Kirsti went into work and started to evacuate animals from their outdoor enclosures. At this point, the hurricane began to veer toward southwest Florida, but was still expected to make landfall more than a 100 miles north of Naples, sparing her town. That afternoon, calls began to stream in from her parents and her in-laws, who lived along the Florida coast. It was decided that they should take shelter in the couple’s house. By that evening, Kirsti’s two-bedroom, one-bath house was suddenly packed with family and a menagerie of pets.

On Wednesday morning, Justin injected Kirsti with the last dose of her medication. Southwest Florida was flooding, and parts of the state were losing power, but they hadn’t heard anything from the clinic. Their appointment was supposed to be the next day. As far as Kirsti knew, the procedure was still on track.

Since the beginning of the 2000s, climate change researchers have warned that a warmer planet produces stronger and more damaging hurricanes. In 2020, 30 named storms developed in the Atlantic, setting a record. University of Pennsylvania researchers recently predicted that this year’s Atlantic hurricane season will include 33 named storms. Study after study has demonstrated that the convergence of a warmer, wetter atmosphere and a higher sea-surface temperature causes tropical depressions to grow into hurricanes more quickly. A study published late last year said storms have become twice as likely to develop from a weak tropical cyclone into a Category 3, 4, or 5 hurricane within a 24-hour window — a process meteorologists call “rapid intensification.” The growing intensity of hurricanes has prompted some climate scientists to suggest adding a sixth category to the Saffir-Simpson scale, for hurricanes with winds faster than 192 miles per hour.

Hurricane Ian was a prime example of a storm charged by climate change. It strengthened from a Category 3 into a Category 4 hurricane in under 24 hours. Ian is just one of several major hurricanes that have struck the southern and southeastern coasts of the United States in the past decade — regions that are particularly vulnerable to damage during the Atlantic hurricane season. In places like Florida, Louisiana, Georgia, Puerto Rico, and Texas, it’s becoming increasingly evident that communities and the infrastructure they rely on are ill-prepared for intensifying storms.

Hurricane Harvey, a Category 4 storm that hit Texas in 2017, submerged hundreds of roads, collapsed bridges, and damaged more than 300,000 homes. That same year, Category 4 Hurricane Maria decimated Puerto Rico’s aging power grid, plunging the island into darkness for nearly a year — the longest power outage in U.S. history. In 2020, Category 4 Hurricane Laura barreled into southwest Louisiana, displacing thousands of residents and nearly destroying the city of Lake Charles. The city was still clearing wreckage caused by Laura, the most powerful storm to hit southwest Louisiana since record-keeping began, when another hurricane, Category 2 Delta, carved a nearly identical path of destruction through the state. Lake Charles continues to recover four years later.

Fertility clinics are just as vulnerable to storms as any other infrastructure. When Hurricane Ida hit New Orleans in 2021, Nicole Ulrich, a doctor at Audubon Fertility Center, experienced firsthand the challenges intensifying hurricanes pose to these centers. Similar to Hurricane Ian, Ida progressed so rapidly that it caught the city and clinic off guard.

Forecasters “thought it was maybe going to be a [Category] 1 or a 2, and then it was going to be a 3, and then all of a sudden, it was going to be a 4. At that point, there really should have been a mandatory evacuation, but there wasn’t enough time,” said Ulrich. “We had to close the clinic at that point, because there just wasn’t another option.”

As a result, Audubon had to cancel at least 10 IVF cycles, and delay the start of several others. This included patients who were preparing for embryo transfers, and others who had started injecting the hormones needed for egg retrieval. The clinic also had some embryos growing in the lab. It usually takes five or six days to tell which embryos are healthy and suitable for freezing, but Ulrich’s clinic had to quickly decide to freeze them early, on days two and three instead, just in case their backup power generator failed.

Once the clinic was back up and running, it took months before Ulrich and her team could fit in all the patients whose cycles had been canceled or delayed — patients who were anxiously awaiting the chance to restart the process.

“For most people, waiting a month is not going to make that big of a difference. But when you’re in that moment and you’re 42 and you know your egg count is low, it feels like just the most devastating thing that could happen,” said Ulrich. “There is a chance that, especially when you get closer to 43, it might make a difference.”

The embryos Audubon froze early had to be thawed in order to mature and then refrozen. The clinic is still analyzing data from that change in protocol to understand if it affected pregnancy outcomes.

Thanks to that experience, Ulrich published a paper in 2022 that calls for more research on the topic of IVF and climate change, with a focus on the particular challenges posed by rapidly intensifying hurricanes. “It had a huge impact on our clinic and our patients, and for months afterwards, we were still dealing with the aftereffects,” she wrote.

But the experience taught Ulrich lessons other IVF facilities could benefit from. Ulrich said she’d love to see clinics establish better relationships with other fertility treatment centers in their region so that patients could transfer to them in times of disaster. She also encourages clinic staff to review their emergency action plans to ensure they are prepared to meet the changing nature of storms, and to be ready to make decisions quickly to salvage cycles and protect embryos. All clinics store embryos in nitrogen tanks, which do not rely on electricity and are typically safe from blackouts or issues with electrical grids. But the labs that embryos mature in before they are frozen do depend on electricity — and if a disaster takes out power for too long, even backup generators can run out of fuel. During Hurricane Katrina, embryos were lost at one clinic for this reason.

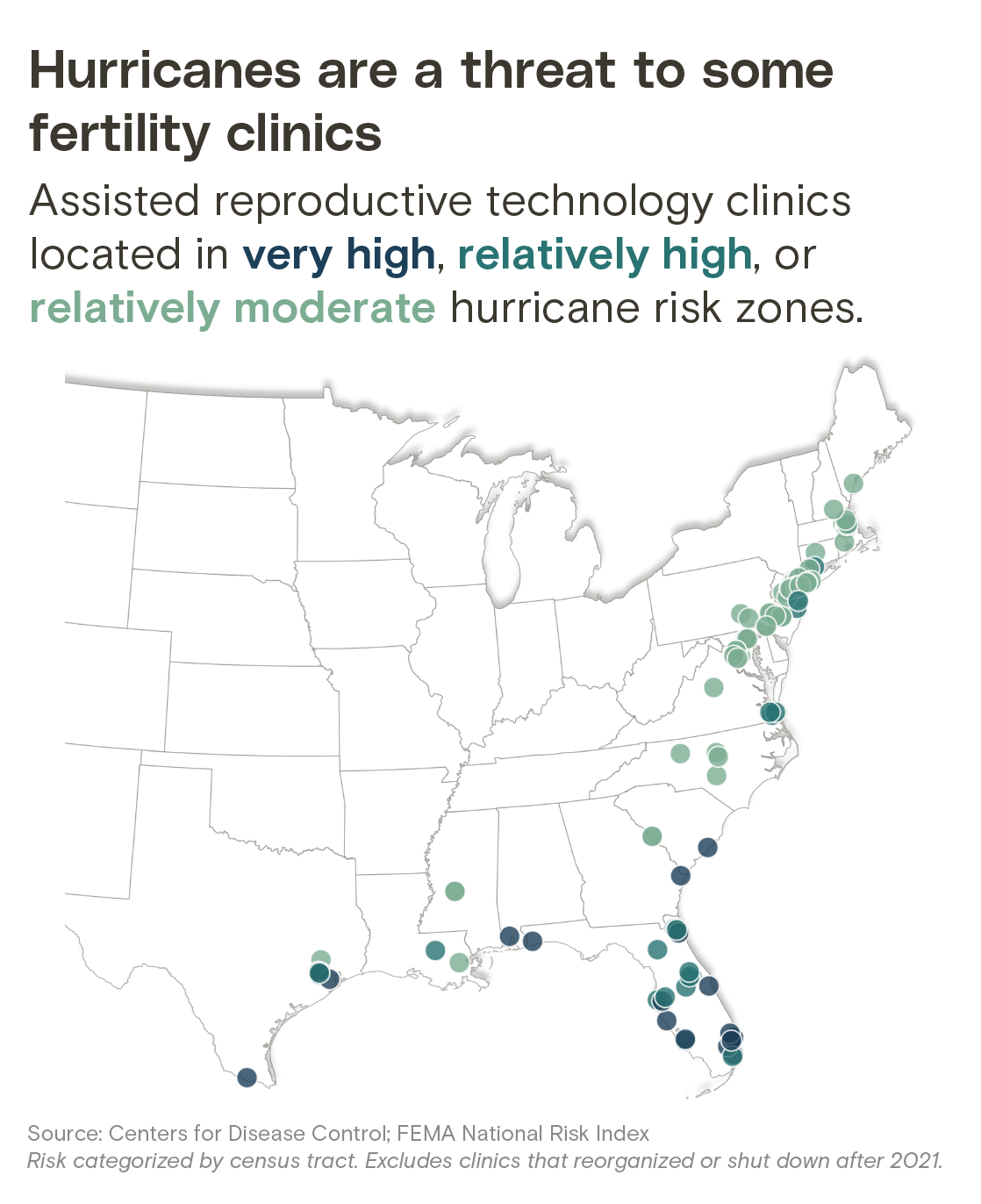

Share of assisted reproductive technology clinics in areas with “very high,” “relatively high,” or “relatively moderate” hurricane risk

| State | Share of clinics in risky zones |

|---|

Table displays only states with at least one clinic in a high-risk area. Risk categorized by census tract. Excludes clinics that reorganized or shut down after 2021.

Source: Centers for Disease Control; FEMA National Risk Index

Chart: Jasmine Mithani / The 19th; Clayton Aldern / Grist

IVF clinics are currently not required to have emergency plans in place, but it is recommended by the American Society of Reproductive Medicine. In 2022, the society published its own paper highlighting the need for clinics to adapt to increasingly threatening hurricane seasons.

“Clearly, climate change means you are having more extreme weather events, and [I] think that, like every other part of society, from homeowners to hospitals, fertility clinics have to think a bit more about how they can build more resilient systems,” said Scott Tipton, chief advocacy and policy officer with the American Society of Reproductive Medicine.

Within a few hours of Kirsti’s final hormone injection, she saw her nurse’s name light up on her phone. Before ducking into her bedroom to get some privacy from the houseguests, she exchanged a despairing glance with Justin. “I just looked at my husband and I was like, ‘It's not happening, it's not happening,’ and I took the phone call.”

The nurse immediately assured her that her embryos were safe but confirmed her suspicion: The clinic was closing because of the storm, and Kirsti wouldn’t be able to go through with the transfer the following day. In fact, they would have to start her cycle all over again. (Kirsti’s clinic did not respond to requests for comment.)

“It just felt like our earth was shattered,” she said. Five weeks of hormone injections had taken their toll on her body, both emotionally and physically. She had grown to dread the shots, which caused swelling in her buttocks, thighs, and stomach. “We had spent so much money, so much time. I was covered in bruises,” she said. “I hung up the phone and I just lost it. I lost it. I wasn’t even angry. I was just heartbroken.”

Aside from the sadness she felt over yet another hurdle in their fertility journey, Kirsti thought about all the money she and Justin had poured into the treatment, including borrowing from family. The $2,500 the couple had spent on fertility medications that month evaporated the moment Kirsti’s phone rang. If the couple were to restart the embryo transfer process, they would have to spend thousands more.

The average cost of one cycle of IVF in the U.S. is $12,400, but prices can vary depending on the clinic, the cocktail of fertility medicines used, and the number of embryos collected and frozen. Some clinics charge as much as $30,000 per cycle. And many patients need more than one cycle to get pregnant.

Because IVF is so costly, there is a large access gap between those who can afford the treatment and those who can’t. In a 2021 survey administered by researchers in Illinois who sought to better understand the demographics of IVF patients in the state, 75.5 percent of the respondents were white, 10.2 percent Asian, 7.3 percent Black, and 5.7 percent Latina.

Despite these hurdles, IVF is becoming increasingly popular. The treatment allows people to delay pregnancy for any number of reasons — to build a career, save money for a family, or find the right partner. And it’s a crucial tool for people struggling with infertility. In the U.S., that’s 1 in 5 women.

More than 40 percent of all American adults now say they have used fertility treatments or know someone who has had them, as the number of people who delay childbearing grows. In 1970, the average age of a person giving birth for the first time was 21.4. In 2021, that average was six years higher.

As IVF has grown more common, it has also become the target of political and legal attacks. In February, Alabama’s Supreme Court, dominated by conservative judges, ruled that embryos created in vitro should be thought of as children for the purposes of wrongful death lawsuits. The ruling had an immediate chilling effect on clinics throughout the state. A month later, Alabama lawmakers extended criminal and civil immunity protections to IVF clinics for their day-to-day operations. Manufacturers of products used in the course of IVF treatment get some immunity protections under the new law, too. But the law still leaves providers at risk because it doesn’t challenge the court’s assertion that embryos are people.

This decision also has possible implications for doctors practicing IVF when a disaster hits, said Ulrich. “If you had an incubator on a power grid that failed, and you didn't have a backup or the backup failed — those embryos would have been lost,” said Ulrich. Perhaps patients would see the loss as an unavoidable accident — or perhaps they’d sue for wrongful death, she said. “It’s another reason to be careful.”

In the days after Hurricane Ian made landfall, Kirsti spent her time worrying about her family, her neighborhood, her house, and the animals at the zoo. Beneath it all, she felt a deep sense of despair. “I felt like every single piece of me was being hit and like every single thing I had was being ripped to shreds,” she said. But there was no doubt in her mind that she and Justin would try again.

For months, Kirsti’s embryos stayed safely frozen while she and a few other women she knew from the clinic waited to have their transfers rescheduled. The hurricane’s disruption meant their appointments would come after others already on the books, so she wouldn’t be penciled in until December, delaying her procedure even longer. The clinic agreed to waive the fees for the postponed transfer, but Kirsti and Justin still had to pay out of pocket for the costly medications.

On Halloween, she once again started preparing her body to carry a baby, taking a slew of medications and undergoing daily hormone injections. On the first of December, she completed the long-awaited transfer. Two weeks later, her doctors confirmed what she already knew based on a home test: Kirsti was pregnant. “I was over the moon,” she said.

She was also nervous: “We had been pregnant before and it always ended in loss.” As she and her husband put together the baby’s zoo-themed room they felt hopeful — but nothing was certain until August 8, 2023, when she gave birth to a healthy baby girl named Gracie.

That day, the Naples coast was hot and sunny. As they looked down at their newborn daughter, Kirsti and Justin reflected on all it took to get there, after nearly four years of trying to start their family. “She was here and in our arms, and we just had this moment,” she said. “It was like, ‘We did it.’”

A few weeks later, Florida was hit by another Category 4 hurricane.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Four lost pregnancies. Five weeks of IVF injections. One storm. on May 30, 2024.

Roger Casupang was working in a coastal clinic on the north side of Papua New Guinea, an island nation of 9 million in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, when a pregnant woman burst into his facility. She was in labor, moments away from delivering twins. She also had a severe case of malaria, a life-threatening mosquito-borne illness common in tropical countries.

Casupang, an obstetrician, quickly took stock of the situation. When the parent is healthy, a twin pregnancy is twice as risky as a single pregnancy. Meanwhile, severe malaria kills nearly half of the people who develop it during pregnancy. The woman was exhausted and delirious. Because many of his patients walked for days to get medical care for standard ailments, Casupang didn’t know which province she had come from or how long she had been traveling before she reached his clinic.

What he did know was that the woman had arrived just in time. “She was actually pushing when she came in,” he said.

Casupang, who was born in one of Papua New Guinea’s highland provinces and had been practicing medicine on the island for the better part of a decade at the time, had seen pregnant women die in less dire circumstances. Against all odds, with limited medical resources and medicines at their disposal, Casupang and the other medical professionals at the clinic were able to deliver the twins safely. Both babies weighed less than three pounds each, a consequence of their mother’s raging infection. The twins were moved to the nursery while Casupang and his fellow physicians worked to stabilize the mother. She was reunited with her babies after 10 days of intensive care. “If this case had presented in a remote facility,” Casupang said, “the narrative would have been very different.”

Casupang’s patient was lucky to survive — but she also benefited from geography. On the coast, doctors see lots of patients with malaria, and many of those patients carry antibodies that protect them from severe infection.

But malaria is on the move.

Temperatures are rising around the world but particularly in countries where the disease is already present. That warming coaxes mosquitoes toward higher elevations, even as temperatures have historically been too cold for the insects to thrive. In these high-altitude areas, mosquitoes are feeding on people who have never had malaria before — and who are much more susceptible to deadly infections.

“When malaria hits new populations that are naive, you tend to get these explosive epidemics that are severe because people don’t have any existing immunity,” said Sadie Ryan, an associate professor of medical geography at the University of Florida.

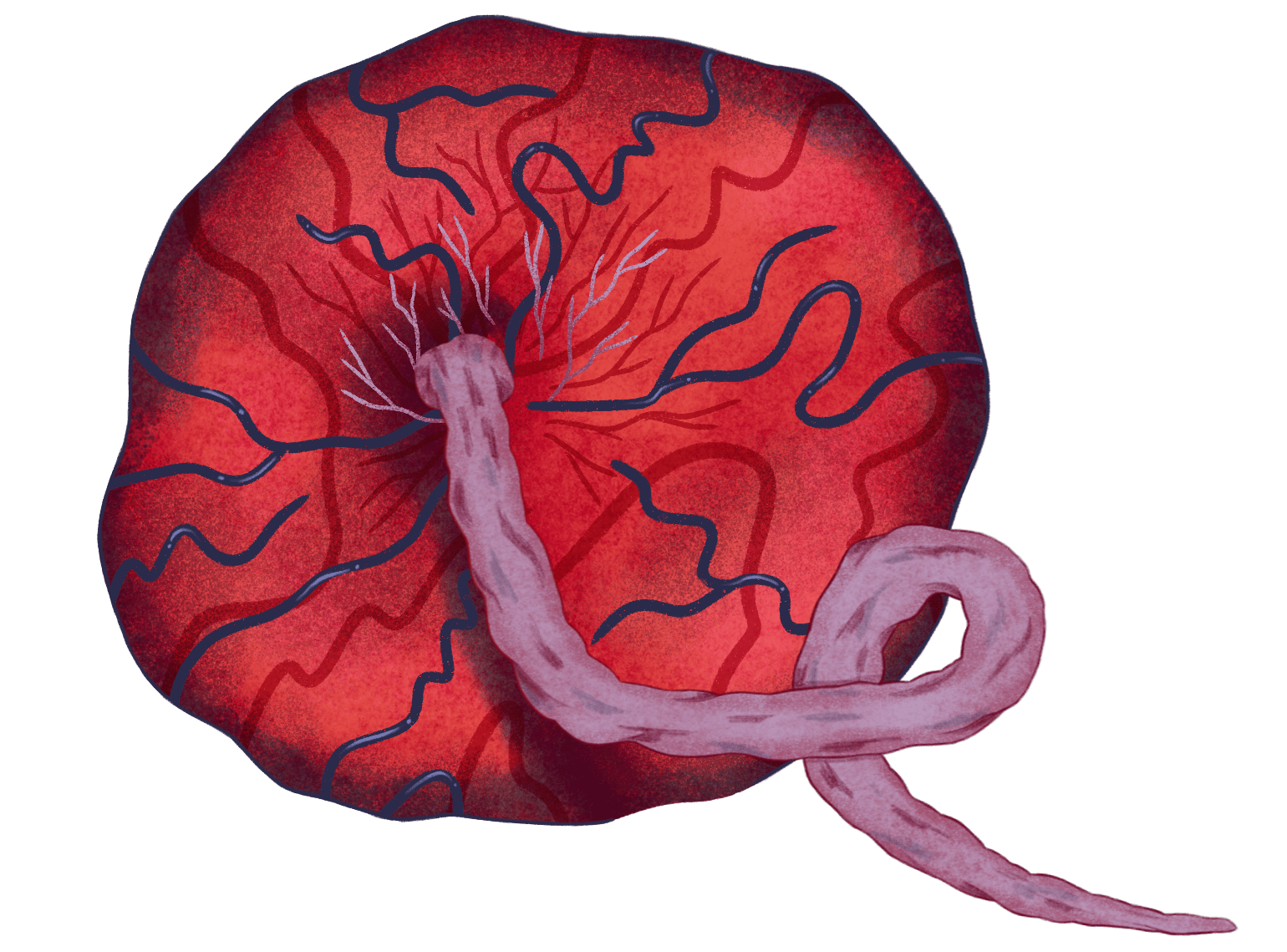

Pregnant people living in highland regions who have never had malaria before are worst-positioned to survive the bite of an infected mosquito. The very act of becoming pregnant creates a potentially deadly vulnerability to malaria. The placenta, the new organ that forms to nourish the fetus, presents new receptors for the disease to bind to.

Pregnant women are three times more likely to develop severe malaria compared to nonpregnant women. For people who can become pregnant, the climate-driven upward movement of malaria mosquitoes poses nothing less than an existential threat.

“In Western countries, especially where malaria is not endemic, there is this perception that malaria has been around for so long that we already know how to deal with it,” said Deekshita Ramanarayanan, who works on maternal health at the nonpartisan research organization the Wilson Center.

But that was never the case, and the perception is especially flawed now, as climate change threatens to rewrite the malaria-control playbook. “Pregnant people are hit with this double risk factor of climate change and the risks of contracting malaria during pregnancy,” Ramanarayanan said.

Hundreds of millions of people get malaria every year, and an estimated 2.7 million die from it, mostly in tropical and subtropical regions. In 2022, 94 percent of global malaria cases occurred in sub-Saharan Africa. High rates of the disease are also found in Central America and the Caribbean, South America, Southeast Asia, and the western Pacific. Papua New Guinea registered over 400,000 new cases in 2022. That same year the country accounted for 90 percent of the malaria cases in the western Pacific.

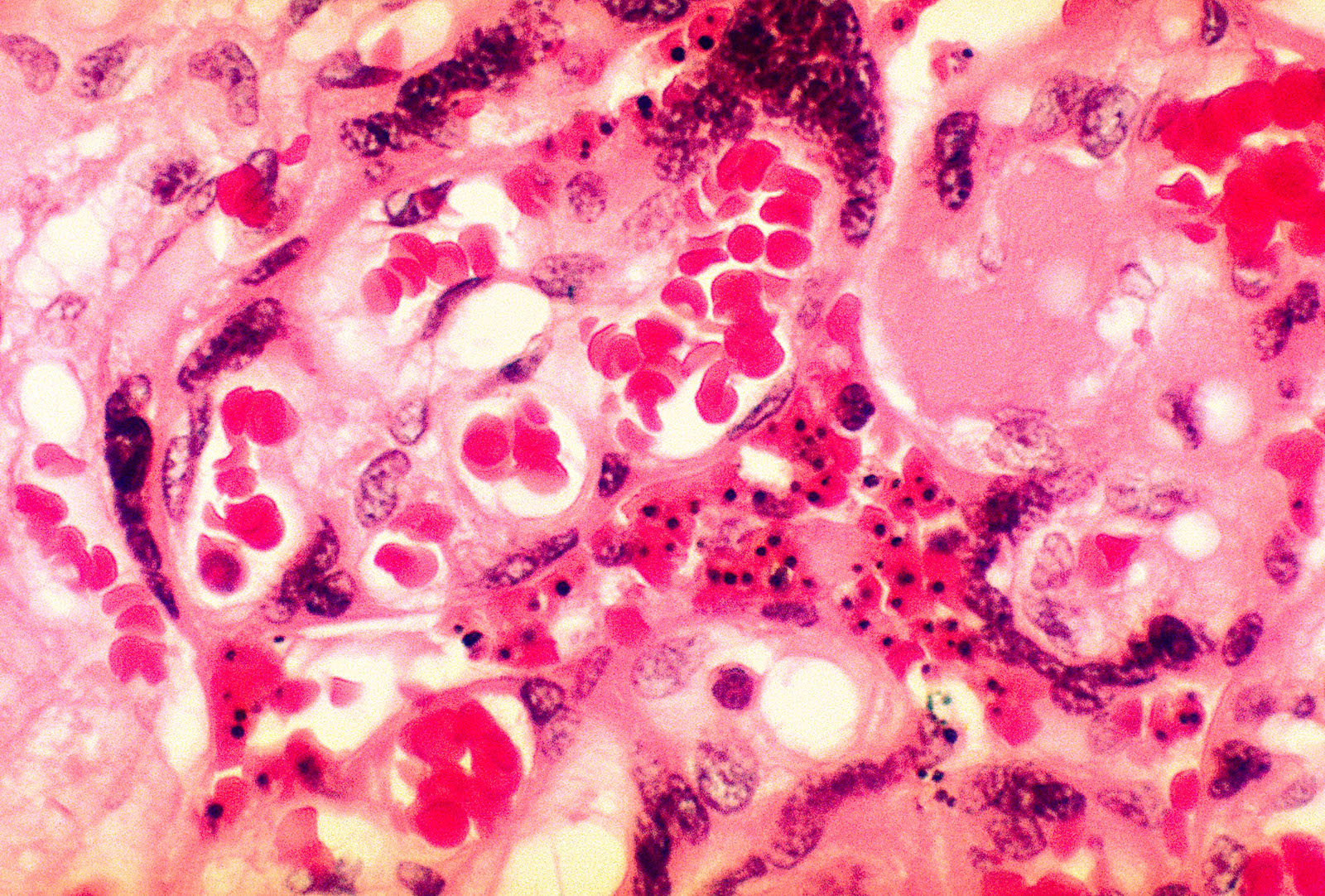

Malaria is carried by dozens of species of Anopheles mosquitoes, also known as marsh or nail mosquitoes. Anopheles mosquitoes carry a parasite called Plasmodium — the single-cell genus that causes malaria in birds, reptiles, and mammals like humans.

When the bite of an Anopheles mosquito introduces Plasmodium into the human bloodstream, the parasites travel to the liver, where they lurk undetectably and mature for a period ranging from weeks to a year. Once the parasites reach maturity, they venture out into the bloodstream and infect red blood cells. The host often experiences symptoms at this stage of the infection — fever, chills, nausea, and general, flu-like discomfort.

The earlier a malaria infection is caught, the better the chances that antimalarial medications can help prevent the development of severe malaria, when the disease spreads to critical organs in the body.

Pregnancy primes the body for infection.

The immune system, when it is functioning properly, engages an arsenal of weapons to ward off bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens. But pregnancy acts like an immunosuppressant, telling the defense system to stand down in order to ensure the body does not inadvertently reject the growing baby. “Your immune system is, on purpose, dialed back so that you can tolerate the fact that you have this fetus inside of you,” said Marya Zlatnik, an obstetrician and gynecologist at University of California, San Francisco Medical Center.

Then there’s the added strain of supplying the baby with enough nutrients, vitamins, and minerals. The body must work overtime to provide for the metabolic needs of two. This factor, exacerbated by poverty, malnutrition, and subpar medical infrastructure in countries where malaria is commonly found, poses enormous challenges to maternal and fetal health. A malaria infection on top of those existing vulnerabilities introduces another, even more challenging set of obstacles.

The disease can produce severe maternal anemia, iron deficiency, or it can spread to the kidneys and the lungs and cause a condition known as blackwater fever. The disorder makes patients jaundiced, feverish, and dangerously low on vitamins crucial for a healthy pregnancy.

“It’s pretty much synonymous with death for many patients up in the rural areas,” Casupang said. Research shows that malaria may be a factor in a quarter of all maternal deaths in the countries where the disease is endemic.

Plasmodium parasites have spikes on them, similar to the now-infamous coronavirus spike proteins, that make them sticky and prone to clogging up organs. If Plasmodium travel to the placenta, the parasites bind to placental receptors and cause portions of the placenta to die off. “It changes the architecture of the placenta and the ways nutrients and oxygen are exchanged with the fetus,” said Courtney Murdock, an associate professor at Cornell University’s department of entomology. The placental clots interfere with fetal growth, and they’re one of the reasons why a pregnant woman is between three and four times more likely to miscarry if she has a malaria infection, and why babies born to mothers sick with malaria come out of the womb malnourished and underweight.

“You see the placenta start to fail,” Casupang said. Fetal mortality is closely tied to how much of the placenta becomes oxygen deprived. “The babies come out with very low birth weights,” he said. If the placental clots are extensive, “they usually die.”

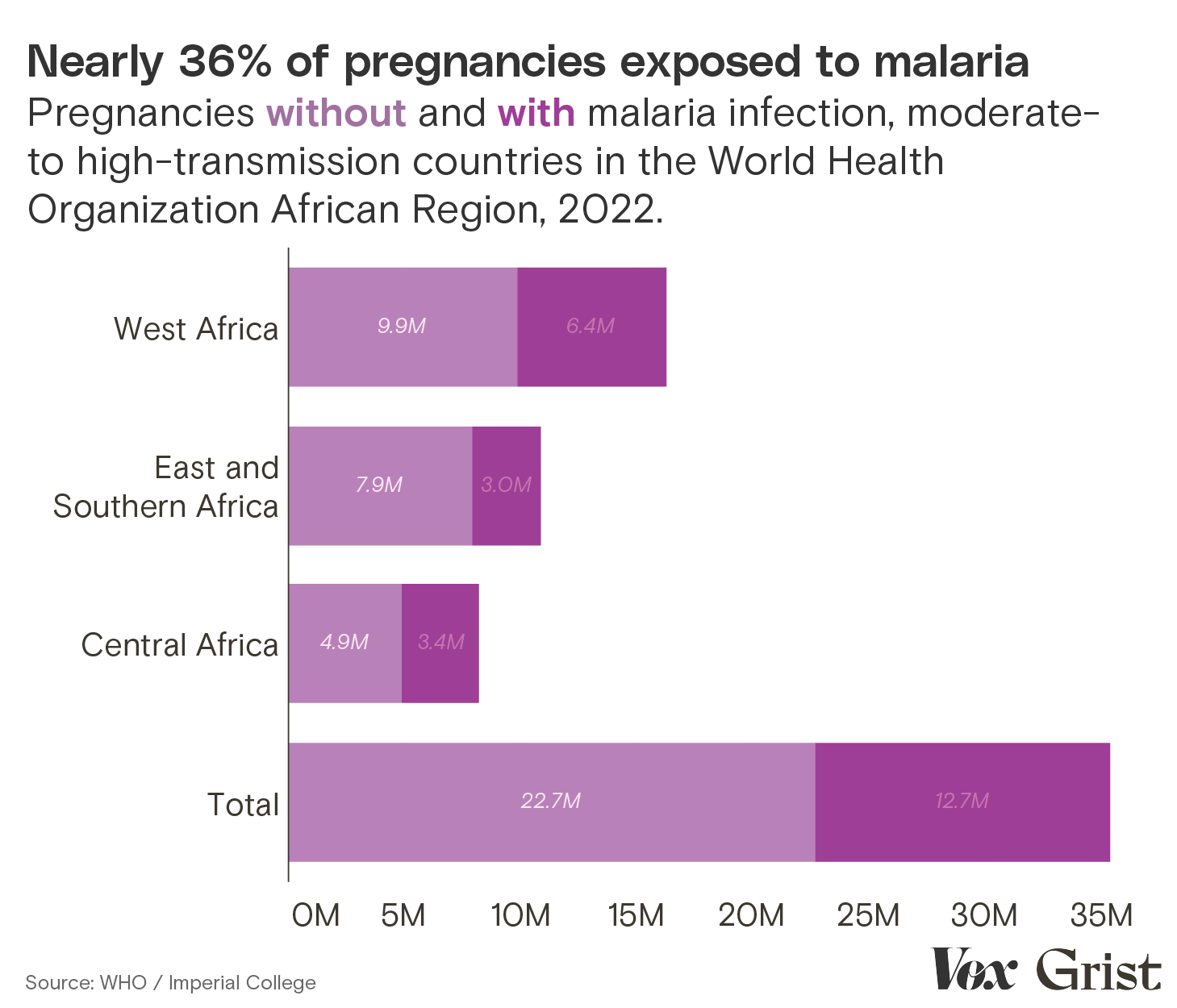

In 2020, approximately 122 million pregnancies — about half of all pregnancies worldwide that year — occurred in areas where people were at risk of contracting malaria. A 2023 study estimated that 16 million of these pregnancies ended in miscarriage, and 1.4 million in stillbirth.

Researchers don’t know exactly how many of those miscarriages and stillbirths occurred in individuals who were bitten by malaria-infected mosquitoes.

However, the World Health Organization estimates that approximately 35 percent of pregnant people in African countries with moderate to high malaria transmission were exposed to the disease during pregnancy in 2022. A widespread lack of health data in poor countries makes it nearly impossible to know how many of those infections resulted in maternal, fetal, or infant death. “Unfortunately, it is only safe to say that we do not have good morbidity estimates at this point,” said Feiko ter Kuile, chair in tropical epidemiology at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

Researchers have said that out of all the high-impact infectious diseases — including Ebola, mpox (formerly known as monkeypox), and MERS — malaria is the “most sensitive to the relationship of human populations to their environment.” In Papua New Guinea, the coastal zones that sit near or at sea level have long had environmental conditions that foster the development and spread of the Anopheles mosquito. Cases of malaria topped 1.5 million in 2020, and the vast majority occurred in the nation’s lowlands.

At 4,000 feet or more above sea level, where some 40 percent of the Papua New Guinean population lives, temperatures have historically been too cold for Anopheles mosquitoes to thrive year-round. There have been seasonal outbreaks of malaria in those zones, but the background hum of malaria present in the lowlands largely disappears above the 4,000 feet mark. At 5,200 feet above sea level, periodic freezes kill mosquitoes and prevent them from establishing widely, making malaria infections there very rare.

But climate change is expanding the areas where Anopheles mosquitoes and the Plasmodium they carry flourish by fostering warmer, wetter environments. Mosquitoes thrive in the aftermath of big storms, when the insects have ample opportunity to breed in standing pools of water.

At the same time, higher-than-average temperatures almost everywhere in the world mark the beginning of a new chapter in humanity’s long struggle to contain mosquitoes and the diseases they carry. Anopheles mosquitoes grow into adults more quickly in warmer weather, and longer warm seasons allow them to breed faster and stay active longer.

This poses problems in areas where Anopheles mosquitoes are already prevalent, and in regions the insects are poised to infiltrate. The mountainous regions of the world — the Himalayas, the Andes, the East African highlands — are thawing as average global temperatures climb. What used to be an inhospitable habitat is becoming fertile ground for malaria transmission.

Like their mosquito hosts, Plasmodium parasites are sensitive to temperature. The two most common strains, Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax, like temperatures in the range of 56 to 95 degrees Fahrenheit. The warmer the weather, the more quickly the parasites are able to reach their infectious stage. A study that examined temperatures suitable to Plasmodium in the western Himalaya mountains predicted that, by 2040, the mountain range’s high-elevation sites — 8,500 feet above sea level — “will have a temperature range conducive for malaria transmission.”

There’s little data on the rate at which Anopheles mosquitoes and the parasites they carry are moving upward in Papua New Guinea, but research shows temperatures across Papua New Guinea were, on average, just under 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees F) warmer between 2000 and 2017 than they were a century prior. A report conducted by the World Bank Group noted that this temperature rise “has been fastest in the minimum temperatures,” meaning climate change jeopardizes the overnight low temperatures that are so essential to mosquito control. Anecdotally, doctors and nurses working in the country’s colder regions say they have seen a familiar pattern begin to change.

Stella Silihtau works in the emergency department at the Eastern Highlands Provincial Health Authority in Goroka, a town of 20,000 that sits at 5,200 feet above sea level on a major road that connects the scattered highland cities and towns to the communities along the coast. Silihtau and her colleagues are no strangers to malaria. Hundreds of people in Goroka and surrounding highland towns grow cash crops like coffee, tea, rubber, and sugarcane and ferry them down to the coast every week to sell to plantations and community boards. The highland dwellers are bitten by mosquitoes at lower elevations, and end up at the hospital where Silihtau works weeks later, sick with malaria. Over the past year, she’s seen unusual cases starting to crop up.

“We’ve been seeing a lot of patients that are coming in with malaria,” said Silihtau, who grew up in the lowlands. Many of these cases have been in people who have not traveled at all. “We’ve seen mild cases, severe cases, they go into psychosis,” she said.

Silihtau and her colleagues don’t have the time or staff to keep close track of how many locally acquired malaria cases have been treated at the hospital over the past year. But Silihtau estimates that when she first started working at the hospital in Goroka two years ago, she saw one case per eight-hour shift, or none at all. Now, she sees between two and three cases of malaria per shift, some of them in individuals who have not traveled outside the boundaries of Papua New Guinea’s highland zones. “It’s a new trend,” Silihtau said.

The new dangers that the upward movement of malaria mosquitoes pose to pregnant people are obfuscated by positive signals in malaria cases globally.

Global malaria deaths plummeted 36 percent between 2010 and 2020, the dive driven by wider implementation of the standard, relatively low-cost treatments that research shows are incredibly effective at preventing severe infections: insecticide-treated mosquito nets, antimalarial drugs, and malaria tests.

This promising trend stalled in 2022, when there were an estimated 249 million cases of malaria globally — up 5 million from 2021. Much of the increase can be attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic, which slowed various global infectious disease control efforts as health care systems tried to contain an entirely new threat. Funding for malaria control is also falling short. Countries spent a total of $4.1 billion on malaria in 2022, nowhere near the $7.8 billion in funding the World Health Organization says is necessary annually to reduce the global health burden of the disease 90 percent by 2030.

Meanwhile, cases have been rising in step with the spread of a mosquito called Anopheles stephensi, a species that can carry two different strains of Plasmodium and, unlike the rest of its Anopheles brethren, thrives in urban environments. Efforts to control malaria in both urban and rural settings are stymied by the quickening pace and severity of extreme weather events, which scramble vaccination and mosquito net distribution campaigns, shutter health clinics, and interrupt medical supply chains. Record-breaking storms, which destroy homes and public infrastructure and create thousands of internal migrants, force governments in developing countries to choose where to allocate limited funding. Infectious disease control programs are often the first to go.

The world’s slowly warming highland regions are one small thread in the web of factors influencing the prevalence of malaria. But because of the lack of immunity among populations in upper elevations, the movement of malaria into these zones poses a unique threat to pregnant people — one that may grow to constitute a disproportionate fraction of the overall impact of malaria as climate change continues to worsen.

“Pregnant women are going to be a high-risk population in highland areas,” said Chandy C. John, a professor and researcher at Indiana University School of Medicine who has conducted malaria research in Kenya and Uganda for 20 years. John and his colleagues are in the process of analyzing their two decades of health data to try to tease out the potential effects of climate on malaria cases. “What are we seeing in terms of rainfall and temperature and how they relate to risk of malaria over time in these areas?” he asked. His study will add to the small but growing body of research on how temperature shifts in high elevations contribute to the prevalence of malaria.

Controlling and even eradicating malaria isn’t just possible; it has already been done. Dozens of countries have banished the disease; Cabo Verde recently became the third African country to be certified as malaria-free. “Malaria is such a complex disease,” said Jennifer Gardy, deputy director for malaria surveillance, data, and epidemiology at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, “but that complexity is kind of beautiful because it means we’ve got so many different intervention points.”

In addition to the typical interventions such as mosquito nets, the Papua New Guinea National Department of Health has had some success with medical therapies for people who develop malaria infections while pregnant. Doctors there and in many other malaria-endemic places use intermittent preventive treatment on pregnant women. The antimalarial is administered orally as soon as patients learn they are pregnant and, if taken on regularly, can significantly reduce the chances of severe malaria over the course of gestation. The treatment remains difficult to access in highland regions, as malaria has historically been uncommon there. If governments and hospitals pay attention and get these medicines into places where rising temperatures are changing climatic constraints on mosquitoes, they will save lives.

The smartest solutions are those that address malaria as a symptom of a wider system of inequity. Papua New Guinea is a “patriarchal society where men get the best treatment,” Casupang, who now works for an international emergency medicine and security company called International SOS, said. “Women are pretty much regarded as commodities.” Most married women must seek permission from their husbands to seek medical care at a facility, and permission is not always granted. Many women are also prevented from seeking medical attention by poverty, by the quality of the roads that connect rural villages to cities, and because they don’t recognize the symptoms of malaria or understand the risks the infection poses to themselves and their unborn children, Casupang said. Just 55 percent of women in Papua New Guinea give birth in a health facility, a partial function of the fact that the country currently has less than a quarter of the medical personnel it needs to care for mothers, babies, and children.

“There are quite a number of factors that will determine the outcome of a mother that has malaria,” Casupang said. “The most important thing is access to a health care facility.” He’s one of many experts who argue that better infrastructure, improvements in education, and the implementation of policies that protect women and girls double as malaria control measures — not just in Papua New Guinea but everywhere poverty creates footholds for infectious diseases to take root and flourish.

“Education, a living wage, sanitation, and all of these other very basic things can do so much for a disease like malaria,” John said. “It’s not a mosquito net or a vaccine, but it can make such a huge difference for the population.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Pregnant in a warming climate: A lethal ‘double risk’ for malaria on May 30, 2024.