Despite major efforts like the European Union’s new law to prevent deforestation, forests are disappearing…

The post Is the Miyawaki Method the Answer to Deforestation? appeared first on Earth911.

Despite major efforts like the European Union’s new law to prevent deforestation, forests are disappearing…

The post Is the Miyawaki Method the Answer to Deforestation? appeared first on Earth911.

This story was originally published by the The California Newsroom, a collaboration of public radio stations, NPR, and CalMatters; the nonprofit newsroom MuckRock; and the Guardian. It is republished under a Creative Commons (BY-ND 4.0) license.

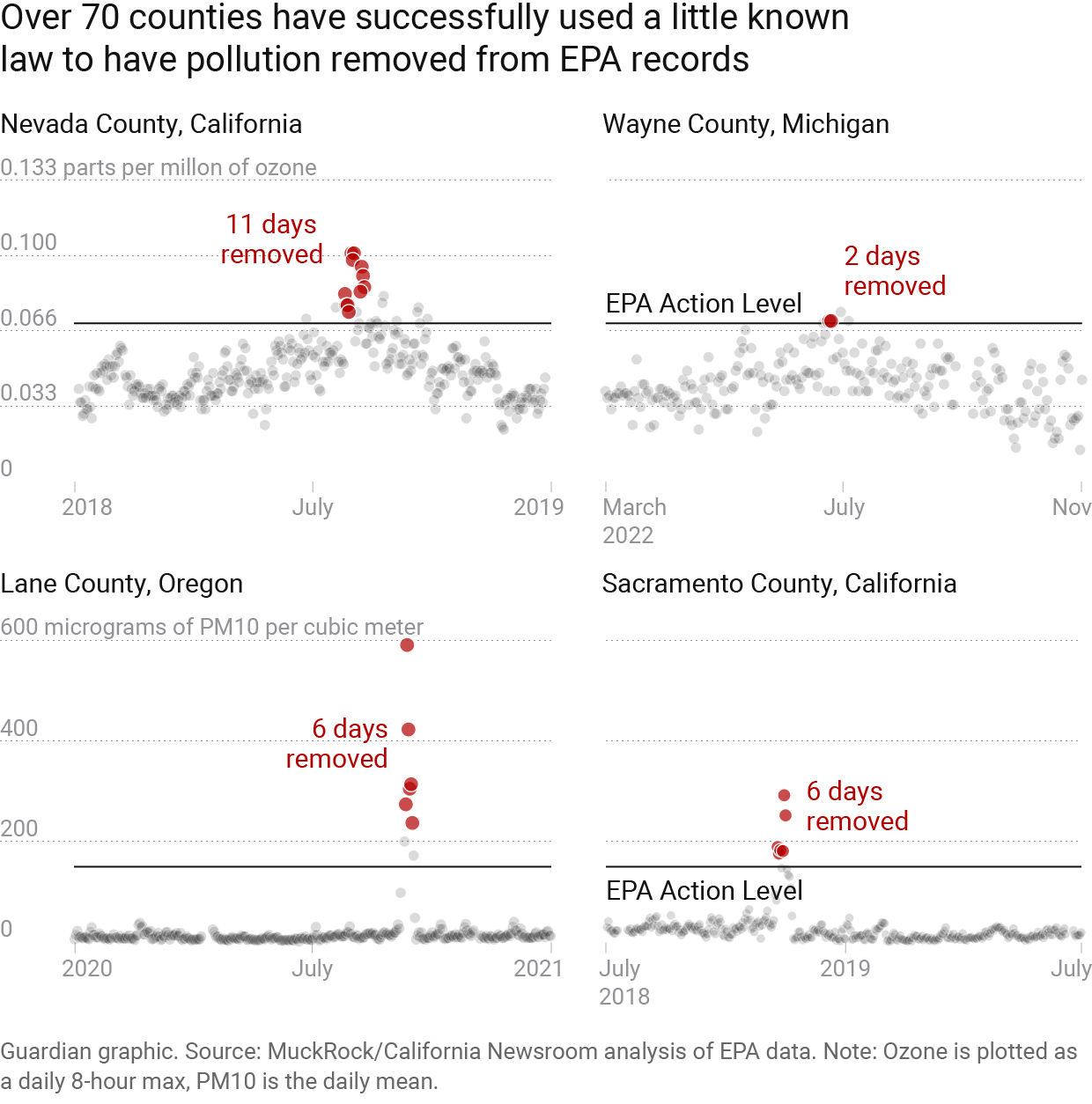

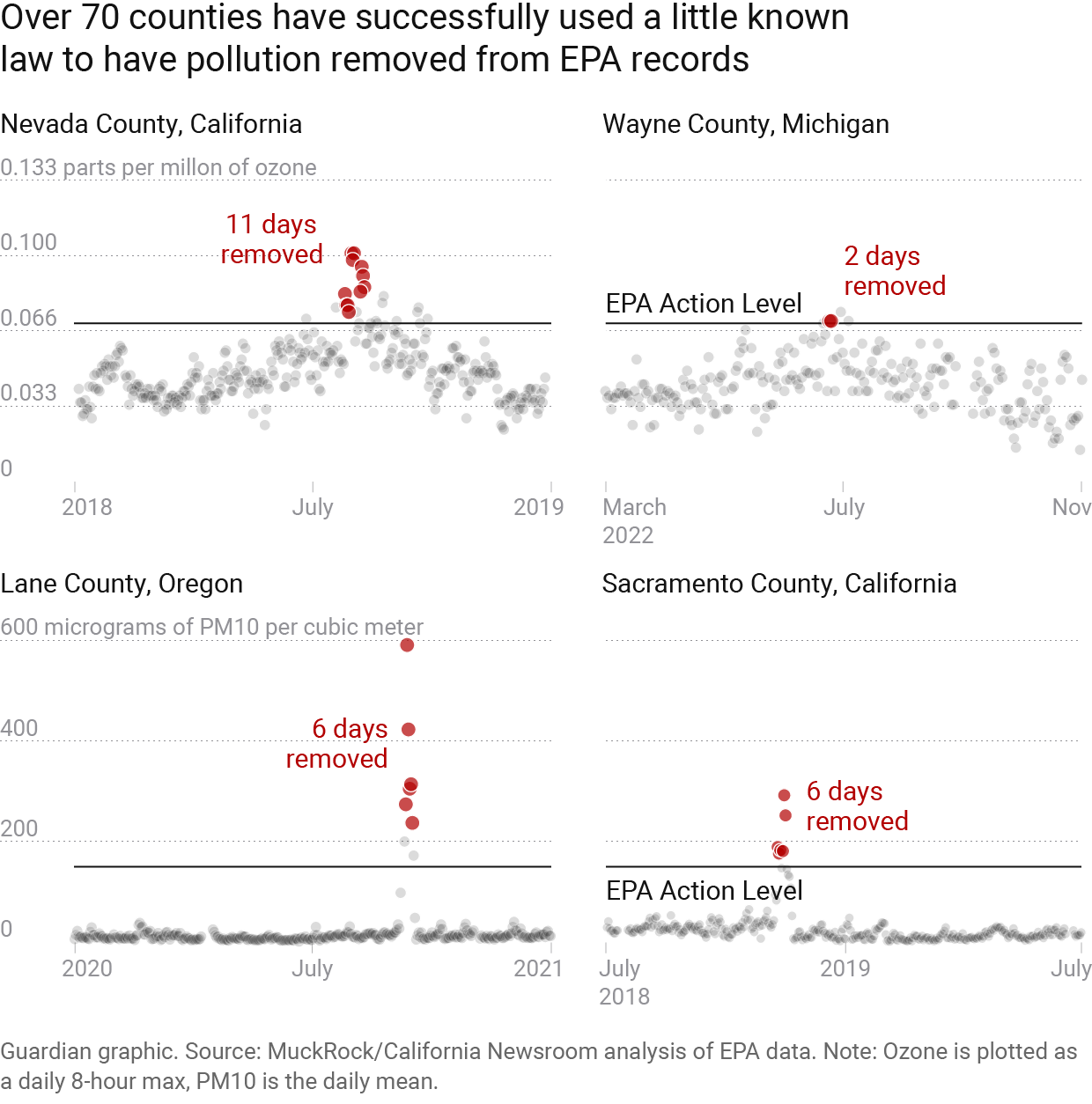

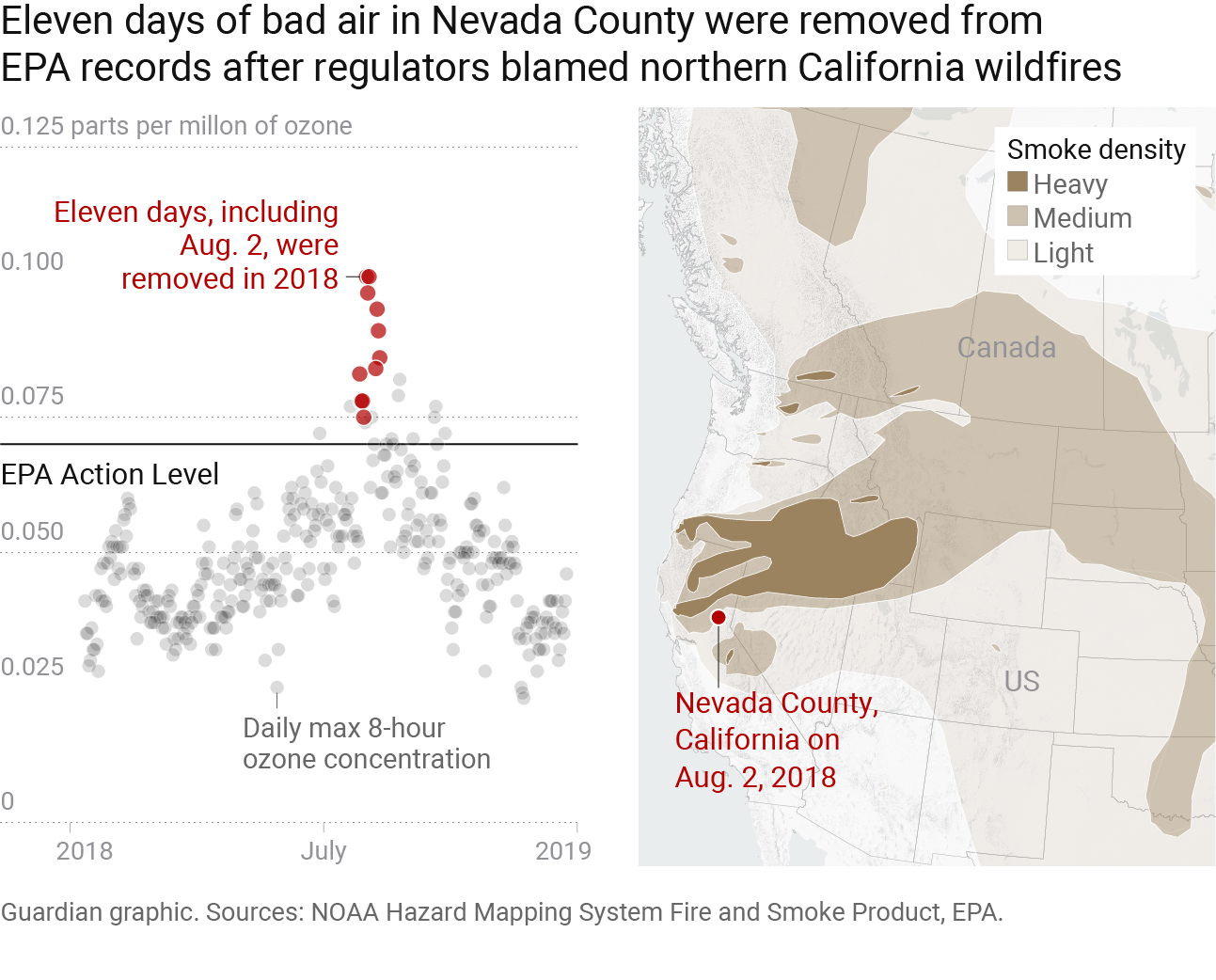

A legal loophole has allowed the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to strike pollution from clean air tallies in more than 70 counties, enabling local regulators to claim the air was cleaner than it really was for more than 21 million Americans.

Regulators have exploited a little-known provision in the Clean Air Act called the “exceptional events rule” to forgive pollution caused by “natural” or “uncontrollable” events – including wildfires – on records used by the EPA for regulatory decisions, a new investigation from The California Newsroom, MuckRock and the Guardian reveals.

In addition to obscuring the true health risks of pollution and swerving away from tighter control on local polluters, the rule threatens the potency of the Clean Air Act, experts argue, at a time when the climate crisis is posing an unprecedented challenge to the health of millions of Americans.

Where the EPA — the U.S. department monitoring air quality — has agreed to exclude bad air days from analysis, “we may have a sort of stable, relatively rosy picture when it comes to our regulatory world in terms of air-quality trends,” said Vijay Limaye, a climate and health epidemiologist at the Natural Resources Defense Council, a nonprofit advocacy group.

The truth is more complicated, and the air dirtier.

“The true conditions on the ground in terms of the air that people are breathing in, day after day, week after week, year after year, is increasingly an unhealthy situation,” Limaye said.

For the summer of 2023, more than 20 states so far, from Wyoming to Wisconsin to North Carolina, have flagged air-quality readings that were far higher than normal. Most of these days came in June, as skies in the midwest and eastern US were blanketed with Canadian wildfire smoke.

We pored over thousands of pages of regulatory documentation, correspondence and contracts, and analyzed hard-to-find public data to better understand how local regulators make use of the exceptional events rule, as global heating sparks extreme wildfires more often.

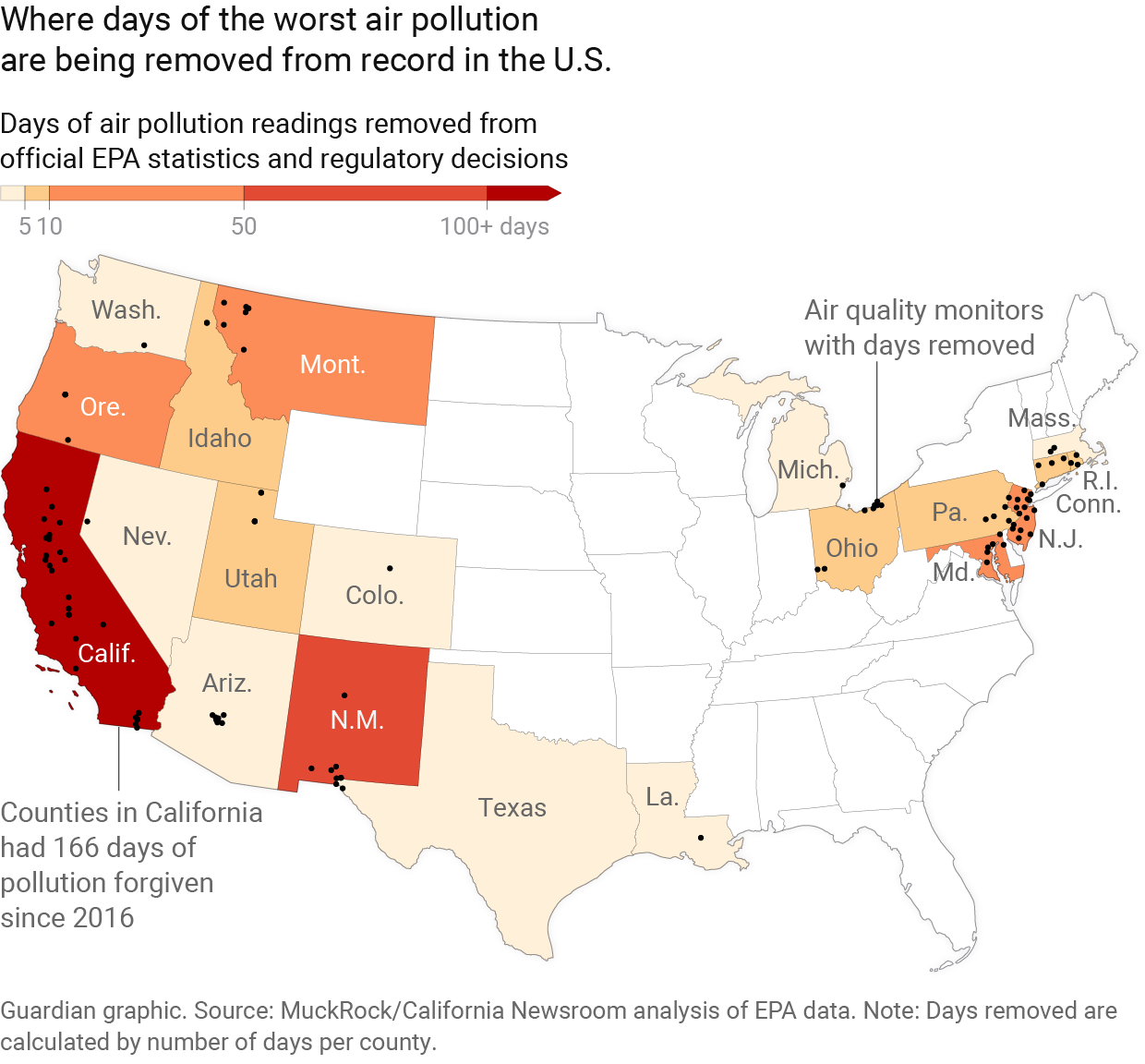

We found that, since 2016, when the EPA last revised the guidance on exceptional events, local regulators in 21 states filed requests with the agency to forgive pollution and, in 20 of those states, had them approved.

In total, local regulators made note of almost 700 exceptional events. The EPA agreed to adjust the data on 139 of them. The adjustments came in more than 70 counties across 20 states. The affected areas stretched from the forested Oregon coast to the Ohio Rust Belt, from the craggy Rhode Island coastline down to the bayous of Louisiana.

In more than half of the states where exceptional events were forgiven, industry lobbyists and business interests pressed to make that happen, sometimes as the only public voice in the regulatory process. Also, to protect the status quo, some regulators spent millions of taxpayer dollars doing research for and making exceptional events requests, sometimes working hand in hand with industry stakeholders.

Meeting air-quality standards matters a lot to industry and politicians. Violations can add up to stricter, more costly and potentially unpopular pollution controls.

Critics say the growing use of the exceptional events rule for wildfires is of deep concern. “You need to level with the public about the number of days when the air quality was unhealthy,” said Eric Schaeffer, a former regulator who directs the Environmental Integrity Project.

“We have saved more lives in this country because we cleaned up the air than almost any other environmental policy,” said Michael Wara, the director of the climate and energy policy program at Stanford’s Woods Institute for the Environment. “And that’s what’s being undermined.”

“The world has changed,” he said. “We are living in a different world when it comes to wildfire and all of its consequences, including air pollution.”

In response to written questions, the EPA said it takes all air pollution seriously.

“Wildland fire and smoke pose increasing challenges and human health impacts in communities all around the country,” Khanya Brann, an EPA spokesperson, wrote. “EPA works closely with other federal agencies, state and local health departments, tribal nations, and other partners to provide information, tools, and resources to support communities in preparing for, responding to, and reducing health impacts from wildland fire and smoke.”

The EPA also pointed to “mitigation plans”, in which air districts that have experienced repeated exceptional events must create plans for educating and notifying the public about the pollution risk, as well as “steps to identify, study, and implement mitigating measures” like limiting use of wood-burning stoves and wetting down unpaved roads before dust storms.

In the U.S., clean-air policy long allowed local governments to write off some wildfire smoke on a case-by-case-basis as “unrealistic to control” or “impractical to fully control”. But in 2005, the Republican senator Jim Inhofe of Oklahoma, who has long denied the climate crisis, won a years-long battle to amend the Clean Air Act. The new rule gave local officials more opportunity to exclude pollution from regulatory consideration for an array of events, from fireworks displays and volcanic eruptions to wildfires and even unusual traffic events.

At first, the rule was used most successfully in a handful of south-western communities where high winds created a recurring problem of dust pollution. Over time, local regulators have turned to exceptional events for wildfires more and more often to reach air-quality goals.

Our analysis of local and EPA records found that in 2016, air agencies flagged 19 wildfire events as potential exceptional events. In 2018 and 2021, 52 and 50 wildfire events were flagged. In 2020, 65 were.

“The uptick in exceptional events is absolutely consistent with what we see in the air pollution data,” said Marshall Burke, an associate professor of global environmental policy at the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability. Smoke is accounting for a higher proportion of overall air pollution, and it’s going up quickly, Burke said — not just in the western U.S., but nationwide.

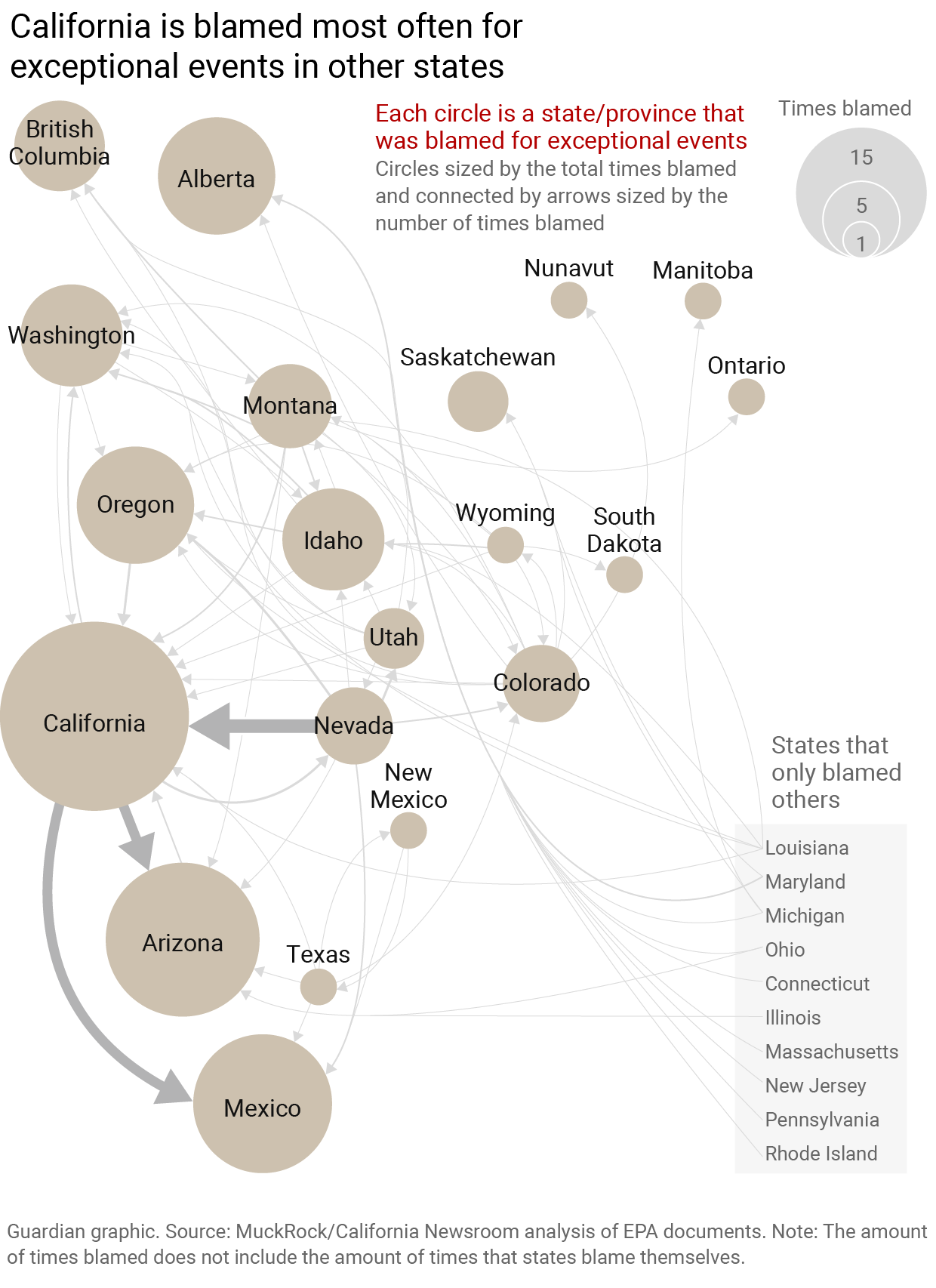

No state is blamed more for smoke pollution than California, followed by Oregon and Canadian provinces, according to our analysis. Western states are more likely to point fingers at each other, while states in the midwest and north-east place the blame on Canadian provinces like Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Wildfire smoke is a dirty and complicated polluter. Limaye, of the NRDC, called it a “toxic soup of air pollution.” It carries soot and ash, regulated as particulate pollution, as well as hydrocarbons and other gases that, cooked in sunlight, help form ground-level ozone. It’s a growing concern for public health, both near the source and thousands of miles away. Smoke, especially from a long-burning fire, can travel long distances and linger at dangerous levels for weeks at a time.

We analyzed data recorded at air monitors nationwide. For every U.S. county, on a day where the EPA excluded any data, we counted that day. Our analysis found that the total number of wildfire-related bad air days erased from regulatory consideration in counties nationwide was nearly double that of bad air days related to high winds: 236 compared to 121.

When wildfire caused air pollution, the rule was applied to more monitor readings over multiple days, not just to exclude particulate pollution but also smog or ozone.

“It is a lot of time,” said John Walke, a lawyer for the NRDC.

One or two violations at a single air monitor can flip an area from meeting air standards to missing the mark, according to Walke. Three or four violations over several years can prompt increasingly strict local pollution controls. “So a lot is riding on one, or two, or three violations,” he said.

The recent experience of California’s Nevada County may offer a glimpse of a smokier future. So far, the exceptional events rule has removed 16 days from the record there in the last five years.

Ozone levels are rising in the background in this foothill community, according to Julie Hunter, the interim chief for the Northern Sierra Air Quality Management dDstrict. She said more trucks and warmer temperatures are to blame. More frequently now, she said, wildfire smoke is like a “pancake,” settling flat across the rural valley, stuck until conditions change.

During one fire in 2021, a thick plume of smoke covered the sun in the town of Grass Valley. “We couldn’t see past down the driveway,” said Dr. Alinea Stevens, the medical director at the Chapa-De Indian Health clinic in town.

Stevens remembered doctors and nurses moving among patients under the menacing amber skies, N95 masks snug on their faces to protect against Covid-19 — and wildfire smoke.

Over hours, the clinic’s security guards got lightheaded and developed headaches. “We told them, you need to wear N95 masks, too,” Stevens said. “That kind of prolonged exposure to those things was very real.”

After fires in 2018 and 2020, the EPA wiped more than two weeks of ozone pollution in the district from the record. That didn’t get Nevada County all the way to a clean bill of health, but local regulators avoided having to tighten rules on local emissions. Hunter, the local regulator, said her district is likely to seek more exceptional events there, including for fires in the last two years.

“If we take out wildfire smoke as one of the things that we look at, then we’re not going to be addressing problems that really affect our community here,” said Stevens, who directs the health clinic. The surge of asthma and other health problems from smoke can be overlooked when it happens in a rural community, she said: “I think it’s maybe a way that we don’t put enough attention into fixing something that can be fixed.”

Officials at the California Air Resources Board stress that state law works toward mitigating the effects of climate change, and state policies are supposed to minimize the risk of catastrophic fire.

“We really are trying to pull out all the stops,” Michael Benjamin, the chief of CARB’s air-quality planning and science division, said. Practically, he added: “We and the air districts in California will continue to take advantage of the exceptional events provisions in the Clean Air Act to try to show attainment.”

When it comes to showing attainment, the stakes are high.

Scrubbing smoke from regulatory accounting allows local governments and business to continue as usual, since the practice obscures the toll wildfires take on public health.

It also ignores the ways that the climate crisis is altering how people decide where to live across the U.S.

In 2017, Maitreyi Siruguri and her husband woke in the night to a sky lit unnaturally orange. They left their Santa Rosa home with their young children in the early hours of the morning; the fire that eventually swirled through went on to kill 22 people and destroy more than 5,600 structures.

Afterward, “I was starting to sense the emotional drain, from everyone having to go through this,” she said. She searched the internet with worry about how smoke could harm her children, then three and seven years old.

In 2021, they left for the suburbs of Chicago. They could afford to buy a house; the family would be closer to friends and relatives — and further, she hoped, from wildfire and smoke.

Growing up in India in the 1980s and 1990s, and working as a climate educator, Siruguri knows very well that there is no escape hatch leading away from environmental problems. “We are all inheriting this, in every part of the world,” she said.

Wara, of Stanford’s Woods Institute, argues that such an inheritance requires investment. Rather than trying to protect the status quo, he said, governments could make a new cost-benefit analysis.

“It would not be unreasonable” to boost spending significantly to manage public and private lands to minimize smoke, “something like what we think is reasonable when it comes to coal-fired power plants, which is billions of dollars per year”, he said. “Because the harms that are being created by the smoke are large.”

This summer, as air quality worsened across Illinois from Canadian fires, Siruguri worried anew in Naperville. On a late July day, when smoke pollution had returned, she brought her child to soccer camp, and asked the camp’s director whether the air was healthy.

He didn’t have an answer. “He was like, well, we kind of wait till somebody tells us what to do or you make the decision for your child,” she said.

Siruguri believes the government must work to stop climate change, including by switching energy sources away from fossil fuels. She believes that when officials talk to the public, they should be honest about how smoke is changing air over time.

“It’s hard for the general public to know. The next time I see bad air quality, I will be looking for how that’s getting recorded,” Siruguri said. “It is concerning that these decisions are made behind the scenes, almost.”

Walke of the NRDC agreed: “The worst possible outcome is lying to the American people about whether the air they breathe is safe or unsafe.”

Smoke, Screened: The Clean Air Act’s Dirty Secret is a collaboration of The California Newsroom, MuckRock and the Guardian. Molly Peterson is a reporter for The California Newsroom. Dillon Bergin is a data reporter for MuckRock. Emily Zentner is a data reporter for The California Newsroom. Andrew Witherspoon is a data reporter for the Guardian.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How a little-known pollution rule keeps the air dirty for millions of Americans on Oct 17, 2023.

Drought is usually associated with lack of rainfall, but there are other factors, like snowmelt and groundwater, that can affect the water levels of streams and rivers.

In a new study, researchers from University of California, Riverside (UCR), found that drought impact can persist for as long as three-and-a-half years in rivers and streams despite precipitation from a series of storms, a press release from UCR said.

The total water level of streams is measured by two factors: total water level, affected by rainfall and snowmelt, and baseflow, the share fed by groundwater.

“People often just use rain as an indicator of drought because it’s easier to measure. But there are other kinds of drought that each have their own impacts,” said Hoori Ajami, the study’s corresponding author and associate professor of groundwater hydrology at UCR. “We needed a new way to see how long it takes for one form of drought to become another form.”

Baseflow droughts are studied by fewer researchers, and there had not previously been an accurate measurement technique for them. Since lack of baseflow significantly impacts ecosystem services, as well as water management, the researchers chose to turn their focus on this important aspect of hydrology.

The study, “Comprehensive assessment of baseflow responses to long-term meteorological droughts across the United States,” was published in the Journal of Hydrology.

The category of drought that affects rivers and streams is called hydrological drought, to which baseflow belongs. Baseflow impacts water availability for drinking, bathing and irrigation. It affects plants, wildlife and the overall health of ecosystems. Infrastructure stability could also be impacted by severe hydrological drought.

In order to develop a method for defining the start and end points of hydrological droughts in specific locations, the researchers looked at three decades’ worth of data from 350-plus locations around the U.S.

The research team only looked at baseflow on rivers and streams that did not have any dams or reservoirs and had not been impacted by human activity.

The results showed that a hydrological drought’s beginning and end is dependent on a variety of factors, including a location’s geography and typical climate.

A wide array of lag times were found between the end of a drought due to lack of rainfall and the conclusion of a baseflow drought. For instance, streams in parts of Kansas took 41 months to recover, but those in Pasadena’s Arroyo Seco area took nearly a year.

“When we are looking at water management strategies, it is clear we cannot implement a one-size-fits-all solution everywhere, for every stream. Our approaches need to be site specific,” said lead author of the study Sanghyun Lee, who is now a postdoctoral fellow with the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service in Oklahoma, in the press release. “When I first came to California in 2016, people asked me, ‘Is the drought over?’ They wanted to know if our watersheds had recovered. This new study shows it may take another few years until they get back to normal.”

The team’s results were consistent with earlier studies finding that water recovery in underground aquifers also experiences a delay in responding to lack of rainfall. Aquifers are an important water source for agriculture, as well as rivers’ baseflow.

Too much pumping of groundwater during drought could lead to sinkholes, which can cause shifts or even the collapse of buildings and other types of infrastructure.

“One key message we want to send is that people must be careful about managing the water they have,” Lee said in the press release. “Because of rising temperatures, baseflow drought is getting longer and more severe in many parts of the country. And because watershed boundaries often cross state or international lines, preserving precious water resources will require more cooperation.”

The post Rivers Can Take Years to Recover From Drought, Research Finds appeared first on EcoWatch.

Solar is a major contributor to the renewable energy mix, with everything from solar lights and heating to solar TVs and refrigerators.

Now, there is the Stella Terra, the first off-road solar-powered car, which recently completed a test drive of 620 miles across north Africa without recharging.

“We are pushing the boundaries of technology. With Stella Terra, we want to demonstrate that the transition to a sustainable future offers reasons for optimism and encourages individuals and companies to accelerate the energy transition,” said Wisse Bos, team manager of Solar Team Eindhoven, in a press release from Eindhoven University of Technology.

Students from Eindhoven University of Technology designed the two-seater, which crossed a variety of landscapes during the test, reported The Guardian.

“Stella Terra must withstand the harsh conditions of off-roading while remaining efficient and light enough to be powered by the sun. That is why we had to design almost everything for Stella Terra ourselves, from the suspension to the inverters for the solar panels,” Bos said in the press release.

The moss green vehicle is powered entirely by solar panels on its rounded roof, which means it can run even in remote areas where there are no electric vehicle (EV) charging stations. It is also designed to drive on multiple surfaces so that it can be used for emergency deliveries and services, said the team’s events manager Thieme Bosman, according to CNN.

“Morocco has a huge variety of landscapes and different surfaces in quite a short distance,” Bosman said, and the car was tested “on every type of surface that a car like this could encounter.”

With a top speed of 90 miles per hour, the solar car’s battery has a range of about 441 miles on regular roads and 342 miles off-road on a sunny day. When the sun is obscured by clouds, the Stella Terra could have a range of about 31 miles or even less.

“It was an incredible trip with a positive ending. Stella Terra’s efficiency was hard to predict. That’s why we weren’t sure if we would make it on solar power. During the ride, Stella Terra turned out to use 30 percent less energy than expected. We were able to drive the entire trip on the sun’s energy and did not depend on charging stations,” Bos said in another press release from Eindhoven University of Technology.

Bos said the solar vehicle is a decade ahead of any other car on the market, The Guardian reported.

“We are pushing the boundaries of technology,” Bos said.

Stella Terra comes with a rechargeable lithium-ion battery so it can run over shorter distances on less sunny days. Its solar panels also provide enough electricity for phone and camera chargers and cooking devices.

After initial steering system issues, the car did well in its road tests from Tangier, Morocco, through Fes to the Sahara Desert.

“We hope this can be an inspiration to car manufacturers such as Land Rover and BMW to make it a more sustainable industry. The car was actually very comfortable in the off-road conditions as it is very light and does not get stuck,” said Bob van Ginkel, the project’s technical manager, according to The Guardian.

The car’s solar panel converter had 97 percent efficiency in turning absorbed sunlight through the photovoltaic cells into electrical charge.

The weight of Stella Terra is about a quarter of an average midsize SUV, which requires larger and heavier batteries to power them than standard EVs, reported CNN.

“(One of) the benefits of the solar panels on top is that we can have a much smaller battery because we are charging while driving,” said van Ginkel.

The car also has “lightweight and robust” materials to reduce its weight, as well as an aerodynamic design that lessens drag.

Solar Team Eindhoven previously produced a campervan, and Stella Terra includes elements of its design. The car has seats that fully recline into a bed, and its solar panels extend to both maximize its charging capabilities and create an awning to provide shade.

One of the biggest challenges in building vehicles that run on solar power is that surface area for the solar panels is limited. Production of the highly efficient solar panels capable of generating enough power for long distances is expensive.

Sponsors provided funding for the not-for-profit team that designed Stella Terra. Van Hulst said more work needed to be done on the design before it would be ready to be put on the market.

“We aim to also inspire not only everyday people, but also the automotive industry, the Ford and Chryslers of the world, to think again about their designs and to innovate faster than they currently do,” Bosman said, as CNN reported. “It’s up to the market now, who have the resources and the power to make this change and the switch to more sustainable vehicles.”

The post Solar-Powered Car Completes 620-Mile Test Drive Across North Africa appeared first on EcoWatch.

In September, Brazil’s Supreme Court ruled that marco temporal, a legal theory that would have limited Indigenous claims to land and opened those territories to extractive industries like mining and agriculture, was unconstitutional. The marco temporal case spent 16 years moving through the courts.

But following the ruling, Brazilian lawmakers approved legislation that would make marco temporal legal anyway, putting Indigenous lands and communities at risk again.

It’s estimated that Indigenous peoples safeguard nearly 80 percent of the planet’s remaining biodiversity, with the Brazilian rainforest containing almost a quarter of all terrestrial biodiversity and 10 percent of all known species on Earth. However, over the last four years, under former president Jair Bolsonaro’s policies, deforestation in the Amazon rose 56 percent, with an estimated 13,000 square miles of land destroyed by development and an estimated 965 square miles of Indigenous territories lost to extractive industries.

Brazil’s agribusiness sector, which holds significant influence over the country’s conservative Congress, has supported efforts to make marco temporal law, citing economic development as the key reason to adopt the legislation. With passage, the law would mark a specific time for when Indigenous land claims could be accepted: If Indigenous communities weren’t on the land they claimed in 1988 — when the Brazilian constitution was passed — they would have no claims to those lands, opening them up for development.

According to Land Is Life, an international Indigenous rights advocacy group, beyond ignoring the Supreme Court’s ruling, the bill infringes on the rights of Indigenous peoples. Global watchdogs like Cultural Survival, an organization promoting the self-determination of Indigenous peoples, plan to fight for the protection of Indigenous lands.

A coalition of seven Indigenous Brazilian organizations have sent an appeal to the United Nations denouncing violence against Indigenous peoples and warning that the approval of the marco temporal bill could lead to more. They have also urged President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva to veto the bill.

In the run-up to his election, Lula said he would create a Ministry of Indigenous Affairs headed by an Indigenous person, recognize Indigenous land claims, put a stop to illegal mining on Indigenous territories, and rebuild the National Indian Foundation, or FUNAI.

The bill now awaits Lula’s approval or veto, but even with a veto, lawmakers can override it with a majority vote in each chamber.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Marco temporal: the anti-Indigenous theory that just won’t die on Oct 16, 2023.

A major port in Manaus, Brazil has hit its lowest water level since records began in 1902 as a long drought continues in the region. The new low surpassed the last lowest recording from 2010.

Manaus, Brazil is a connecting point for the Rio Negro and the Amazon River. As of Oct. 16, the Rio Negro level was 13.59 meters. When records began in 1902, the level was at 16.78 meters, and its lowest point since then was 13.63 meters, recorded on Oct. 24, 2010, according to the port website.

An ongoing drought may cause further declines, as this new record low was hit after the river lost 10 centimeters from Oct. 15 to Oct. 16.

“We have gone three months without rain here in our community,” Pedro Mendonca, who lives near Manaus in Santa Helena do Ingles, told Reuters. “It is much hotter than past droughts.”

The drought is expected to continue at least through December, according to Brazil’s Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, Reuters reported. El Niño conditions could be making the drought worse.

Aside from the depleting river level, the extreme weather has been causing many significant problems in the region. Over 100 Amazon river dolphins were found dead in early October, and although the exact cause is under investigation, experts suspect the drought and extreme heat could be connected to the deaths.

As of Oct. 13, Manaus had some of the worst air quality globally because of wildfires. The Associated Press reported that Brazil’s Amazonas state recorded over 2,700 wildfires in just the first 11 days of the month. October is typically considered the start of rainy season, which lasts through April.

“It has been very painful both physically and emotionally to wake up with the city covered in smoke, experience extreme temperatures exceeding 40 degrees Celsius (104 degrees Fahrenheit), and follow the news that the river waters are disappearing,” Mônica Vasconcelos, a climate perception researcher at Amazonas State University, told The Associated Press.

Reuters reported that the current ongoing drought has affected at least 481,000 people, threatening drinking water and access to food for communities around Manaus. Food, water, medications, and other supplies are typically transported throughout the region by the river. The depleted levels have also made locals concerned about the water quality.

Luciana Valentin, who lives in Santa Helena do Ingles, told Reuters, “Our children are getting diarrhea, vomiting, and often having fever because of the water.”

The low water levels could ultimately impact the millions of people that depend on the water in the Amazon basin. CNN reported that there are emergencies declared in over 20 cities, including Manaus.

The post Major Port in Amazon River Drops to Lowest Water Level in 121 Years appeared first on EcoWatch.

Robin Wiener, president of the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries (ISRI), joins the conversation to…

The post Earth911 Podcast: Building A Better Recycling Infrastructure With ISRI’s Robin Wiener appeared first on Earth911.

The Roman Empire fell more than 1,500 years ago, but its grip on the popular imagination is still strong, as evidenced by a recent trend on TikTok. Women started filming the men in their lives to document their answers to a simple question: How often do you think about the Roman Empire?

“I guess, technically, like every day,” one boyfriend said, as his girlfriend wheezed out an astonished “What?” He wasn’t the only one, as an avalanche of Twitter posts, Instagram Reels, and news articles made clear. While driving on a highway, some men couldn’t help but think about the extensive network of roads the Romans built, some of which are still in use today. They pondered the system of aqueducts, built with concrete that could harden underwater.

There are a lot of reasons why people are fascinated by the rise and fall of ancient empires, gender dynamics aside. Part of what’s driving that interest is the question: How could something so big and so advanced fail? And, more pressingly: Could something similar happen to us? Between rampaging wildfires, a rise in political violence, and the public’s trust in government at record lows, it doesn’t seem so far-fetched that America could go up in smoke.

Theories of breakdown driven by climate change have proliferated in recent years, encouraged by the likes of Jared Diamond’s 2005 book Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. The Roman Empire, for example, unraveled during a spasm of volcanic explosions, which led to a period of cooling that precipitated the first pandemic of bubonic plague. The decline of the ancient Maya in Central America has been linked with a major drought. Angkor Wat’s downfall, in modern-day Cambodia, has been pinned on a period of wild swings between drought and monsoon floods. So if minor forms of climate change spelled the collapse of these great societies, how are we supposed to survive the much more radical shifts of today?

Focusing too closely on catastrophe can result in a skewed view of the past — it overlooks societies that navigated an environmental disaster and made it through intact. A review of the literature in 2021 found 77 percent of studies that analyzed the interplay between climate change and societies emphasized catastrophe, while only 10 percent focused on resilience. Historians, anthropologists, and archaeologists have recently tried to fill in that gap. The latest entry is a study that analyzes 150 crises from different time periods and regions, going off a comprehensive dataset that covers more than 5,000 years of human history, back to the Neolithic period. Environmental forces often play a critical role in the fall of societies, the study found, but they can’t do it alone.

Researchers with the Complexity Science Hub, an organization based in Vienna, Austria, that uses mathematical models to understand the dynamics of complex systems, found plenty of examples of societies that made it through famines, cold snaps, and other forms of environmental stress. Several Mesoamerican cities, including the Zapotec settlements of Mitla and Yagul in modern-day Oaxaca, “not only survived but thrived within the same drought conditions” that contributed to the fall of the Maya civilization in the 8th century. And the Maya, before that point, had weathered five earlier droughts and continued to grow.

The new research, published in a peer-reviewed biological sciences journal from The Royal Society last month, suggests that resilience is an ability that societies can gain and lose over time. Researchers found that a stable society can withstand even a dramatic climate shock, whereas a small shock can lead to chaos in a vulnerable one.

The finding is in line with other research, such as a study in Nature in 2021 that analyzed 2,000 years’ worth of Chinese history, untangling the relationship between climate disruptions and the collapse of dynasties. It found that major volcanic eruptions, which often cause cooler summers and weaker monsoons, hurting crops, contributed to the rise of warfare. But it wasn’t the size of the eruption that mattered most: Dynasties survived some of the biggest, climate-disrupting eruptions, including the Tambora eruption of 1815 in present-day Indonesia and the Huaynaputina eruption of 1600 in what’s now Peru.

What matters most, the Complexity Science Hub’s study posits, is inequality and political polarization. Declining living standards tend to lead to dissatisfaction among the general population, while wealthy elites compete for prestigious positions. As pressures rise and society fractures, the government loses legitimacy, making it harder to address challenges collectively. “Inequality is one of history’s greatest villains,” said Daniel Hoyer, a co-author of the study and a historian who studies complex systems. “It really leads to and is at the heart of a lot of other issues.”

On the flipside, however, cooperation can give societies that extra boost they need to withstand environmental threats. “This is why culture matters so much,” Hoyer said. “You need to have social cohesion, you need to have that level of cooperation, to do things that scale — to make reforms, to make adaptations, whether that’s divesting from fossil fuels or changing the way that food systems work.”

It’s reasonable to wonder how neatly the lessons from ancient societies apply to today, when the technology is such that you can fly halfway around the world in a day or outsource the painful task of writing a college essay to ChatGPT. “What can the modern world learn from, for example, the Mayan city states or 17th century Amsterdam?” said Dagomar Degroot, an environmental historian at Georgetown University. The way Degroot sees it, historians can pin down the time-tested strategies as a starting point for policies to help us survive climate change today — a task he’s currently working on with the United Nations Development Programme.

Degroot has identified a number of ways that societies adapted to a changing environment across millennia: Migration allows people to move to more fruitful landscapes; flexible governments learn from past disasters and adopt policies to prevent the same thing from happening again; establishing trade networks makes communities less sensitive to changes in temperature or precipitation. Societies that have greater socioeconomic equality, or that at least provide support for their poorest people, are also more resilient, Degroot said.

By these measures, the United States isn’t exactly on that path to success. According to a standard called the Gini coefficient — where 0 is perfect equality and 1 is complete inequality — the U.S. scores poorly for a rich country, at 0.38 on the scale, beaten out by Norway (0.29) and Switzerland (0.32) but better than Mexico (0.42). Inequality is “out of control,” Hoyer said. “It’s not just that we’re not handling it well. We’re handling it poorly in exactly the same way that so many societies in the past have handled things poorly.”

One of the major voices behind that theme is Peter Turchin, one of the co-authors on Hoyer’s study, a Russian-American scientist who studies complex systems. Once an ecologist analyzing the rise and fall of pine beetle populations, Turchin switched fields in the late 1990s and started to apply a mathematical framework to the rise and fall of human populations instead. Around 2010, he predicted that unrest in America would start getting serious around 2020. Then, right on schedule, the COVID-19 pandemic arrived, a reminder that modern society isn’t immune to the great disasters that shaped the past. “America Is Headed Toward Collapse,” declared the headline of an article in The Atlantic this summer, excerpted from Turchin’s book End Times: Elites, Counter-Elites, and the Path of Political Disintegration.

The barrage of climate catastrophes, gun violence, and terrorist attacks in the headlines are enough to make you consider packing up and trying to live off the land. A recent viral video posed the question: “So is everyone else’s friend group talking about buying some land and having a homestead together where everyone grows separate crops, [where] we can all help each other out and have a supportive community, because our society that we live in feels like it’s crumbling beneath our feet?”

By Turchin’s account, America has been at the brink of collapse twice already, once during the Civil War and again during the Great Depression. It’s not always clear how “collapse” differs from societal change more generally. Some historians define it as a loss of political complexity, while others focus on population decline or whether a society’s culture was maintained. “A lot of people prefer the term ‘decline,’” Degroot said, “in part because historical examples of the collapse of complex societies really refer to a process that took place over sometimes centuries” and would perhaps even go unnoticed by people alive at the time. Living through a period of societal collapse might feel different from what you imagined, just like living through a pandemic did — possibly less like a zombie movie, and more like boring, everyday life once you get accustomed to it.

The Complexity Science Hub’s study suggests that collapse itself could be considered an adaptation in particularly dire situations. “There is this general idea that collapse is scary, and it’s bad, and that’s what we need to avoid,” Hoyer said. “There’s a lot of truth in that, especially because collapse involves violence and destruction and unrest.” But if the way your society is set up is making everyone’s lives miserable, they might be better off with a new system. For example, archaeological evidence shows that after the Roman Empire lost control of the British Isles, people became larger and healthier, according to Degroot. “In no way would collapse automatically be something that would be devastating for those who survived — in fact, often, probably the opposite,” he said.

Of course, there’s no guarantee that a better system will replace the vulnerable, unequal one after a collapse. “You still have to do the work of putting in the reforms, and having the support of those in power, to be able to actually set and reinforce these kinds of revisions,” Hoyer said. “So I would argue, if that’s the case, let’s just do that without the violence to begin with.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Climate change has toppled some civilizations but not others. Why? on Oct 16, 2023.

A record-breaking number of wildfires are blanketing the Amazon with smoke, choking some Brazilian cities and further isolating many Indigenous villages. Over 2,700 wildfires have been reported in the region in the first 11 days of the month — the highest number for any October since 1998, when the record-keeping began.

Air quality became so poor last week in places like Manaus that officials had to postpone the city’s annual marathon, and major universities canceled classes. Philip Fearnside, research professor at the National Institute for Research in Amazonia, said hospitals in the city are full of people who are having respiratory issues. “That should be a wake up call to actually change government policies and individual behavior to actually contain global warming,” he said.

Part of the issue is that the Amazon is in the middle of a severe drought. Water levels in the region’s major rivers have become so low as to be unnavigable, leaving many Indigenous river communities without any way to obtain certain foods, drinking water, or medicine, according to Reuters. Commercial shipping has also been impacted as vessels from the Denmark headquartered company Maersk suspended service in Manaus, after a barge ran aground on the Negro River last month.

“It’s a very worrisome situation,” said Marcia Macedo, an associate scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center. “We’ve seen large fish kills [an event in which numerous dead fish are suddenly observed in a body of water], water levels dropping way faster than normal — lake levels, river levels, like, six meters below what would be expected at this time of year — and definitely the potential for it to get a whole lot worse before it gets better.”

On Wednesday, Indigenous tribes in the region called for the Brazilian government to take more formal action. “We ask the government to declare a climate emergency to urgently address the vulnerability Indigenous peoples are exposed to,” read a statement from the Indigenous umbrella group APIAM, which represents over 60 Amazonian tribes.

As of Friday, almost all of the 62 cities in the state of Amazonas, which includes Manaus, had declared a state of emergency.

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva campaigned on protecting the Amazon from deforestation and further destruction in sharp contrast to his predecessor, Jair Bolsonaro. But while Lula’s administration has upheld Indigenous rights by restoring land in the rainforest and the Brazilian Supreme Court struck down a challenge to Indigenous land rights last month, deforestation remains a major concern.

Tree loss is not the only factor contributing to the current crisis. Climate change as well as El Niño, a weather phenomenon that results in a mass of warm water traveling east over the Pacific and crashing into South America, are also driving dry conditions. “Deforestation contributes to global warming, although fossil fuels globally are the main cause,” said Fearnside. “But global warming is changing climate all over the world, including here in the Amazon.”

Macedo warns that if the cycles that maintain the Amazon rainforests’ trademark wet, rainy, cloudy conditions start to dissipate, the forest could be permanently altered.

“If you get beyond a certain amount of deforestation, you start to affect that recycling of rainwater back to the atmosphere that helps to kind of cool the land surface and also seed new rain clouds,” she told Grist. “If fires get out of control, then you have less forest cover and these droughts are even more intense, and so on and so forth.”

While the system is fairly well understood, Macedo says it’s difficult to pin down at what point things will stop working as usual.

“It’s not linear. It’s not it’s not a simple process to kind of pin down,” Macedo said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Record-breaking wildfires blanket Brazil with smoke on Oct 16, 2023.

Everyone can do a lot at home to protect the environment and our water supply….

The post How Restaurants in Your Community Manage Used Cooking Oil Matters appeared first on Earth911.