Scientists first spotted the Blob in late 2013. The sprawling patch of unusually tepid water in the Gulf of Alaska grew, and grew some more, until it covered an area about the size of the continental United States. Over the course of two years, 1 million seabirds died, kelp forests withered, and sea lion pups got stranded.

But you could have easily missed it. A heat wave in the ocean is not like one on land. What happens on the 70 percent of the planet covered by saltwater is mostly out of sight. There’s no melting asphalt, no straining electrical grids, no sweating through shirts. Just a deep-red splotch on a scientist’s map telling everyone it’s hot out there, and perhaps a photo of birds washed up on a faraway beach to prove it.

Yet marine heat waves can “inject a lot of chaos,” said Chris Free, a fisheries scientist at the University of California, Santa Barbara. It’s not just gulls and sea snails that suffer. Some 100 million Pacific cod, commonly used in fish and chips, vanished in the Gulf of Alaska during the Blob. In British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest, salmon runs – and the fishing industry that depends on them – floundered. The acute warming also triggered a toxic algal bloom that disrupted the West Coast’s lucrative Dungeness crab business.

“It occurred in this place where we have some of the best-managed fisheries in the world, and it still created all these impacts,” Free said.

The Blob was the largest and longest-lasting marine heat wave on record. It might also have been an early glimpse of what’s to come. Fish farms in Chile, scallop operations in Australia, and snow crab pots in Alaska have already fallen victim to oceanic overheating. The economic toll from a single occurrence on fisheries and coastal economies can be as hefty as $3.1 billion. The northeastern Pacific Ocean has experienced several hot spells over the past decade — including the Blob 2.0 — and it’s still experiencing one. As a result, six of the last seven Dungeness crab seasons in California have been delayed. Scientists predict more fisheries will collapse in coming years as climate change — and the ongoing El Niño weather pattern warming the Pacific — spurs more marine heat waves

“I’m really worried,” said William Cheung, director of the Institute of Oceans and Fisheries at the University of British Columbia. “This year we already know the temperature is crazy high.”

As the planet warms, marine heat waves have grown more frequent and more severe. The world’s oceans have absorbed 90 percent of the heat trapped in the atmosphere by greenhouse gasses, and are as hot as humans have ever measured them. During a hotspot in late July, water off the southern tip of Florida reached 101 degrees Fahrenheit — toasty enough to fill a hot tub.

“That’s the highest water temperature I’ve ever heard of in the ocean,” said Steve Murawski, a fisheries biologist at the University of South Florida who has studied oceans for 50 years. “Fish species in particular are great canaries in our collective coal mine.”

Marine heat waves can form in a number of ways, but in general they’re caused by changes in how the air and ocean currents move. When the wind weakens, the sea temperature tends to rise because warm surface water doesn’t evaporate as easily, and colder water doesn’t get churned up from the deep.

Shifts beneath the surface can trigger heat waves, too. One appeared off the west coast of Australia in 2011 when a streak of warm water, some 100 miles wide and 3,000 miles long, surged south. It brought so much warmth from the tropics that ocean temperatures in the region rose almost 11 degrees Fahrenheit above normal. The extreme conditions stuck around for about three months, killing shellfish and forcing scallop and crab fisheries to close. To this day, the kelp forests, which provide crucial habitat for marine creatures like lobsters, haven’t recovered, said Alex Sen Gupta, an ocean and climate scientist at the University of New South Wales.

As the sea grows warmer, marine heat waves are more likely to tip temperatures past the threshold at which coral, kelp, and other marine life can survive. In western Australia, heat waves as intense as the one in 2011 occur roughly once every 80 years. They could arrive as often as once a year by 2100 if countries continue pumping carbon dioxide and methane into the air at high levels. Researchers pegged the chances of the Blob having re-emerged as strongly as it did in the Pacific Ocean in 2019 at less than 1 percent if it weren’t for human-caused warming.

How global warming alters the wind and ocean patterns that spawn marine heat waves remains an “open question,” said Mike Alexander, a climate scientist at the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration. Yet he and Sen Gupta don’t doubt that planetary warming and rising ocean temperatures are making marine heat waves worse.

Fish that prefer cold water, like cod and salmon, are particularly vulnerable to heat waves. Warm water forces them to work harder, which means they need more food to sustain themselves. At the same time, it can make prey less accessible — say, by keeping the zooplankton salmon feast upon from rising to the surface for an easy supper.

The heat also can restrict Pacific cod spawning habitat. Amid extreme heat in the Gulf of Alaska, their numbers tanked between 2013 and 2017. The population struggled to recover, so in 2020 the federal government closed the commercial season for the first time. The fish hauled out of the Gulf of Alaska have accounted for as much as 18 percent of the Pacific cod caught around the world. “It’s kind of devastating,” longtime cod fisherman Frank Miles, based in Kodiak, Alaska, told NPR at the time.

The cod harvest has since reopened, but other fisheries haven’t been as resilient. In 2021, Canada closed 60 percent of its commercial Pacific salmon harvests, which support an industry that employs more than 6,000 people in British Columbia.

As many as 30 million sockeye salmon migrated up British Columbia’s Fraser River in 2010. A decade later, only 291,000 salmon returned. The fish are declining for a number of reasons, but scientists say extreme ocean heat is a major culprit.

“We’re really seeing substantial declines in salmon productivity,” said Catherine Michielsens, chief of fisheries management science at the Pacific Salmon Commission. She said there’s a “real concern” that British Columbia is witnessing the end of its commercial salmon fisheries.

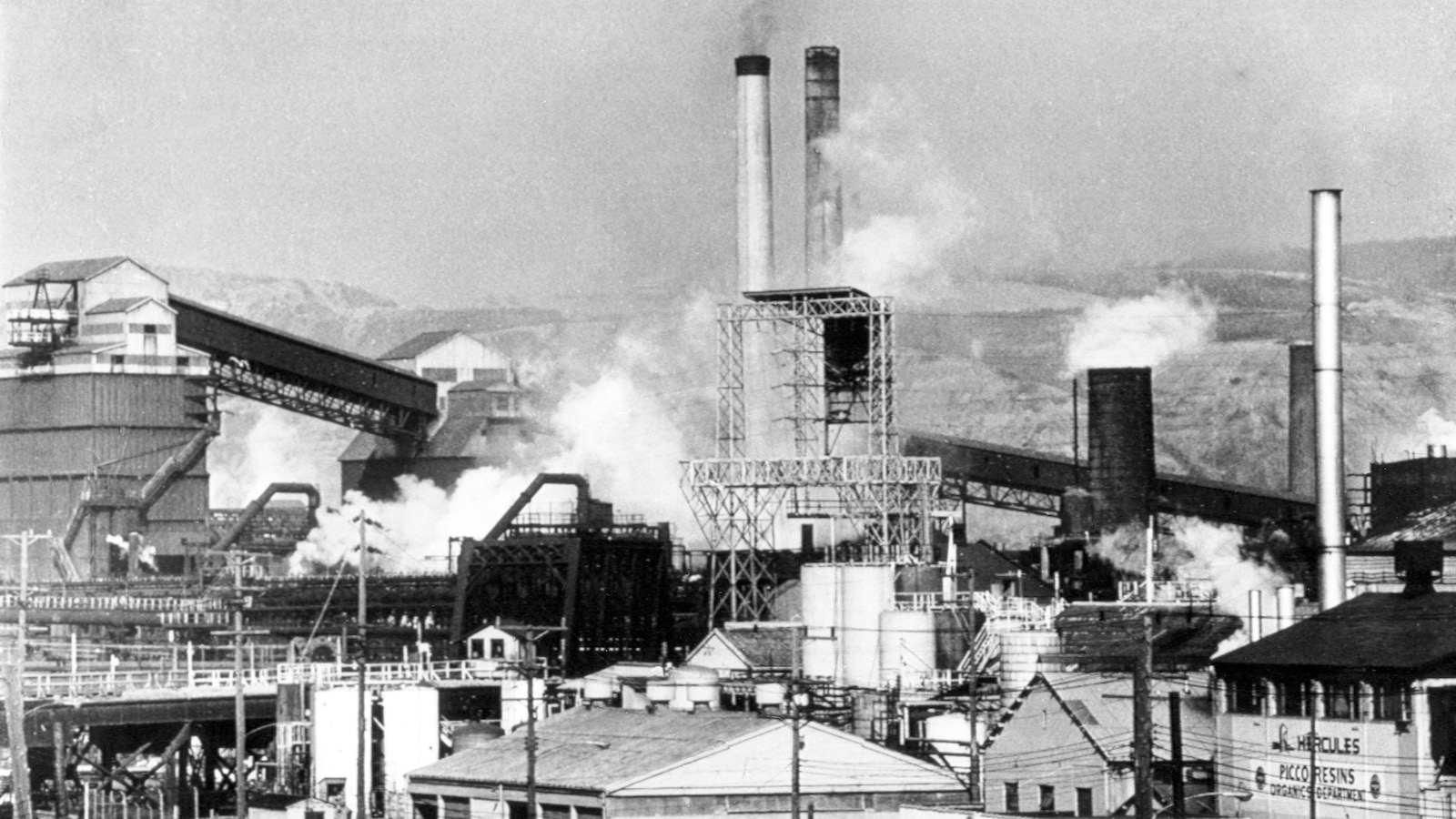

NOAA Fisheries

It’s easy to focus on the heat during a heat wave, but high temperatures aren’t the only threat to fisheries. These weather patterns can cause a cascade of ecosystem changes, from algal blooms to shifting whale feeding grounds, that can wreak havoc on the fishing industry. That’s what happened in late 2015, at the tail end of the Blob. California, Oregon, and Washington delayed their Dungeness crab seasons — one of the West Coast’s most valuable seafood harvests — because the warm water spurred the growth of toxic algae, which catapulted a neurotoxin called domoic acid up the food chain. The crabs were more or less fine, but anyone who ate one might have wound up in the emergency room vomiting, lost some short-term memories, or even died.

When California finally opened its crab season after a four-month closure, West Coast fisherfolk had lost an estimated $97.5 million compared to the previous year. But the Blob added more trouble to the mix. The warm water pushed krill, humpback whales’ main grub, toward the coast and into crabbers’ territory. “There was this intense overlap between the Dungeness crab fishery and humpback whales that led to an enormous spike in humpback whale entanglements in crab-fishing gear,” Free said.

California’s Dungeness harvest rebounded with a strong catch in late 2016 and 2017, but it continues to face closures and delays due to concerns about toxic algae and trapped whales — a stark contrast from the pre-Blob era, when there were very few closures, Free said. “It’s putting the fishery on sort of a precipice right now.”

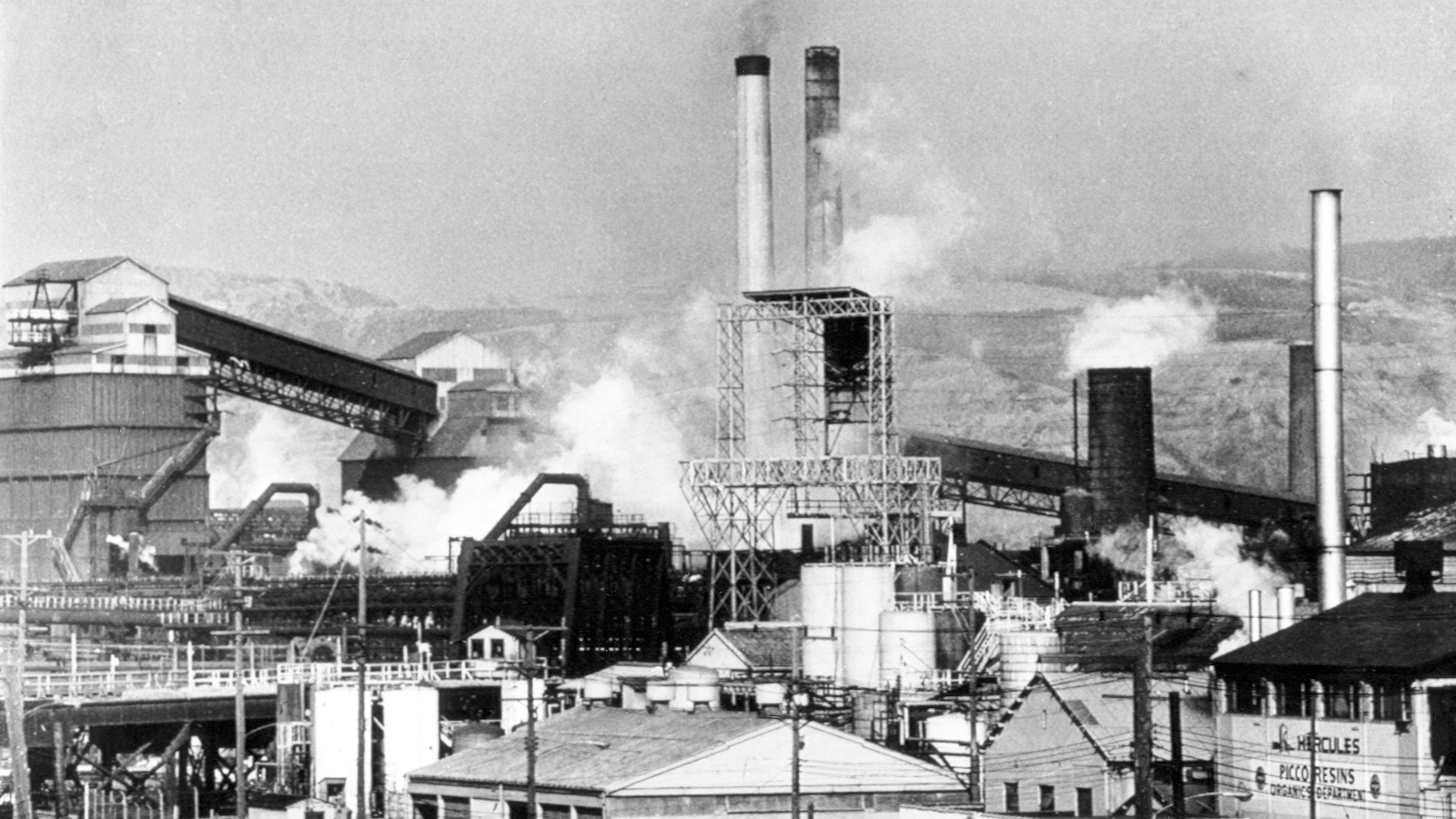

Justin Sullivan / Getty Images

The northeastern Pacific is not the only place where fisheries are feeling the heat. One place of particular concern is the Gulf of Maine — in the northwest Atlantic Ocean — which has experienced a marine heat wave every year since 2012, according to Kathy Mills, a fisheries ecologist at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute.

The Gulf of Maine is like a sink with two faucets: one has cold water moving south from the Labrador Sea, the other has warm water from the tropics moving north along the Gulf Stream. But in recent years the Gulf Stream, a strong current that travels from the Caribbean up the East Coast and across the North Atlantic to Europe, has shifted northward, and the Labrador Current has gotten warmer, Mills said. “Instead of turning them on in the balance they used to be on, now we’re turning on the hot water more, and the cold water is not as cold as it used to be.”

The result is that Maine lobsters, a bounty worth $725 million last year, have been growing faster and shedding their shells earlier. In the short term, the heat has been a boon for those who pluck them from the water, as it spurs growth and boosts lobster numbers. Business has been “booming,” Mills said. But if the trend continues, the critters might be forced to expend so much energy that they won’t be able consume enough food to reproduce or survive.

“Now we’re getting to a point where the temperatures have been so warm for so long, and they are continuing to increase,” Mills said. “We might already be seeing signs that the population is turning off its growth trajectory because of temperature.” One of those signs is that lobster babies are becoming less prevalent. The heat appears to be a reason, among others, that lobster fisheries have already collapsed farther south, where the ocean is warmer, in southern New England.

Joe Raedle / Getty Images

There’s a silver lining, though: Lobsters that forage on cooler seabeds farther north, off the coast of Canada, might benefit from the heat; in fact, those populations have already been turning up in larger numbers. At the same time, “a whole suite” of species from warmer waters in the mid-Atlantic, such as longfin squid and black sea bass, both of which support multi-million-dollar commercial fisheries, have appeared a lot more frequently in the Gulf of Maine, where they used to be quite rare, said Mills.

On the West Coast, a similar range shift is happening with California market squid — footlong, white-and-purple mollusks. (You may have tasted the mild meat of a market squid if you enjoy calamari.) Ever since the Blob, the squid have been seen as far north as Alaska, well beyond their usual habitat in the seas off Mexico and California. The heat wave has ended, but the squid are still hanging out up north. There is talk of opening a new fishery.

“There are always going to be winners and losers,” Murawski said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline The ocean is shattering heat records. Here’s what that means for fisheries. on Aug 11, 2023.