Having fresh, stain-free carpeting, area rugs, and furniture enhances the aesthetics of the room, creating…

The post Better Carpet and Upholstery Cleaners appeared first on Earth911.

Having fresh, stain-free carpeting, area rugs, and furniture enhances the aesthetics of the room, creating…

The post Better Carpet and Upholstery Cleaners appeared first on Earth911.

Did you know that plastic bags account for 11.18% of plastic pollution? If you’re still…

The post We Earthlings: Plastic Bag Pollution appeared first on Earth911.

This story is part of Record High, a Grist series examining extreme heat and its impact on how — and where — we live.

Josh Payne planted chestnut trees six years ago. The rows of nut trees haven’t fully matured yet, but he’s banking on the future shade they’ll provide to shield his animals from sweltering heat.

“We started with that largely because we want to get out of commodity agriculture,” Payne said. “But also because I’m worried that in our area it’s getting hotter and drier.”

Payne operates a 300-acre regenerative farm in Concordia, Missouri, an hour outside of Kansas City, where he raises sheep and cattle. By planting 600 chestnut trees, he is bracing for a future of extreme heat by adapting an agriculture practice known as silvopasture. Rooted in preindustrial farming, the method involves intentionally incorporating trees on the same land used by grazing livestock, in a way that benefits both. Researchers and farmers say silvopastures help improve the health of the soil by protecting it from wind and water, while encouraging an increase of nutrient-rich organic matter, like cow manure, onto the land.

It also provides much-needed natural shade for livestock. According to the First Street Foundation, a nonprofit climate change research group, chunks of America’s heartland — including Kansas, Iowa, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and Missouri — could experience at least one day with temperatures of 125 degrees Fahrenheit or hotter by 2053.

When temperatures rise above 80 degrees, the heat begins to take a toll on animals, which will try to cool themselves down by sweating, panting, and seeking shelter. If they are unable to lower their body temperature, the animals will breathe harder, becoming increasingly fatigued, and eventually die.

Research shows that as the planet warms, livestock deaths will increase. Last year, when temperatures exceeded 100 degrees in southwestern Kansas, roughly 2,000 cattle in the state died; the Kansas Livestock Association estimated each cow to be worth $2,000 if they were market-ready, equaling an economic loss of $4 million. And so far this year, the trend is continuing, with livestock producers in Iowa already reporting hundreds of cattle deaths in the latter half of July alone.

According to the United States Department of Agriculture, or USDA, the ideal temperature for beef and dairy cows ranges between 44 and 77 degrees. Above those temperatures, heat stress causes cattle to produce less milk and decreases their fertility.

Payne’s family farm is a microcosm of American agriculture’s monocrop past and its changing future. He inherited the land from his grandfather, who spent decades tearing trees out of the ground in favor of growing corn and soybeans, using chemical fertilizers for years. His family was hardly alone in doing so: Along with cattle, corn and soybeans make up the top three farm products in the U.S., according to the industry group American Farm Bureau.

Missouri produced nearly $94 billion of agricultural products last year — an economic driver under threat from climate change, which has brought more intense floods and droughts to the state. Last year, the Mississippi River, which flows through Missouri, reached severely low water levels in the face of a historic drought, stopping the barge travel that supports the country’s agricultural economy. When Payne spoke to Grist in July, he was hoping for rain to come soon amid the humid 98-degree heat.

To prevent harm to his 600 sheep and 25 cattle, Payne currently uses portable structures to provide artificial shade while he waits for his chestnut trees to mature. This technology acts like a big umbrella that can be moved as a herd moves, but it doesn’t protect animals from reflected heat and sun rays from the sides the same way a tree canopy can.

In addition to the shade his future nut trees will provide, they’ll be a source of income, too. Payne said it’s likely he’ll make more money on 30 acres of chestnut trees than he would on 300 acres of row crops like corn.

“We’re rethinking the farm process based on climate predictions,” Payne said. “Here we are planting trees in our pastures, so that in 10 to twelve years we can have dappled shade.”

Planting trees in a field seems almost too simple as a way to keep livestock safe and healthy in a hotter world. But Ashley Conway-Anderson, a researcher at the University of Missouri Center for Agroforestry, knows better. She said of all the USDA’s land management systems used to blend forest and livestock, silvopasture is the most complicated, as it requires a delicate balance between planted trees, natural forests and brush, and livestock.

But she will admit the practice is common sense.

“Trees provide shade. That’s the place where you want to be when it’s hot, right?” Conway-Anderson said. “The idea behind a well-managed silvopasture is your taking that shade and dispersing it across the field.”

Conway-Anderson said farmers are adapting their land to silvopastures at a time when agriculture as a whole is wrestling with its role in climate change. The sector accounts for roughly 11 percent of the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions, according to the USDA.

In addition to mitigating extreme heat risks and promoting soil health, trees planted on pastures and fields act as a way to sequester carbon out of the atmosphere through the process of photosynthesis. Project Drawdown, a nonprofit known for its expansive list of practices to prevent further climate harm, estimates that silvopastures could sequester five to 10 times the amount of carbon than a treeless pasture of the same size.

Notably, however, while carbon accounts for the main source of human-caused greenhouse gasses, agriculture’s role in a warming planet largely comes from methane produced by livestock and their waste. But silvopastures help combat that — animals that move around to graze end up trampling on their waste, working it into the soil where it’s repurposed as a natural fertilizer; in contrast, most farm operations pool all livestock waste together in large ponds from which a concentration of methane is then emitted.

Conway-Anderson said agroforestry and silvopastures aren’t always a one-size-fits-all solution. She said farmers are having to “get big or get out,” and aren’t always able to invest the time or money in planting trees or revitalizing woodland they might already own.

“We’ve created an economic system where we have incentivized and subsided specific crops, products, and ways of doing farming and agriculture that has really sucked the air out of the room for smaller, diversified operations,” she said.

On the other hand, she said silvopasture practices can be successful because of their flexibility. Farmers can use trees they already own. They can graze goats, pigs, sheep, cattle, and more under the shade of nut trees, fruit trees, and trees whose trimmings and branches can be harvested and sold to the lumber industry.

“Silvopastures are not a silver bullet,” Conway-Anderson said. “But at this point, I don’t think we have any silver bullets anymore.”

At Hidden Blossom Farms in Union, Connecticut, a rural town located near the border of Massachusetts, Joe Orefice has been methodical in his implementation of silvopasture.

Orefice, a Yale School of the Environment professor of agroforestry, raises tunnel-grown vegetables, figs, and roughly two dozen grass-fed cows that enjoy the shade of apple trees on a 134-acre farm. He said there are currently only two acres of fruit trees the cattle use for cover.

Despite the small acreage, Orefice said, he has focused primarily on soil health, a key aspect of silvopasture management. Without properly maintained grasses and soil, trees won’t grow, and there wouldn’t be any shade for his cattle.

“You need to manage the grasses so young trees will grow,” he said.

In addition to land management and soil health, Orefice said the animal welfare benefits of shade were top of mind.

“I don’t want to eat a big meal if I’m sitting in the sun on a hot and humid day, and we want our cattle to eat big meals because that’s how they grow or keep their calves healthy by producing milk,” he said.

Orefice said a common misconception about silvopasture leads to farmers just taking livestock they own and putting them in the forest without any additional management. He said this can damage soil when livestock, especially pigs, aren’t routinely moved. While it might seem counterintuitive, he said one of the first steps of creating a proper silvopasture from an existing forest is to trim trees and till the soil.

While he only raises 25 beef cattle, Orefice said he’s seen larger farms begin to implement silvopasture practices. He said raising tree crops, like nuts or figs and other fruits, is a boon for farmers who switch to more diversified crop operations versus large, concentrated animal-feeding operations.

For example, Orefice noted that if farmers in the Corn Belt, who are facing continued droughts and an extreme heat future, switched to tree crops, the upfront costs might be expensive and hard. Still, they would eventually make more money on tree crops than on corn or soybeans. The problem, as he sees it, is there is no incentive or safety net for farmers to begin to adopt these practices at the same rate as they have mainstream ones.

“The question isn’t really, ‘Is silvopasture scalable?’” Orefice said. “The question is, ‘Does our economy allow us to scale pasture-based livestock production?’”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Livestock are dying in the heat. This little-known farming method offers a solution. on Aug 15, 2023.

A state judge in Montana gave climate activists a decisive win on Monday when she ruled that the state’s support of fossil fuels violates their constitutional right to a clean and healthful environment.

District Court Judge Kathy Seeley struck down as unconstitutional a state policy barring consideration of the impacts of greenhouse gas emissions in fossil fuel permitting. Her ruling establishes legal protection against broad harms caused by climate change and enshrines a state right to a world free from those harms, creating a potential foundation for future lawsuits across the country.

“We are heard!” Kian Tanner, one of the 16 youth plaintiffs in the lawsuit, said in a statement. He grew up near the Flathead River and testified to watching wildfires come ever closer to his home each year. “Frankly the elation and joy in my heart is overwhelming in the best way. We set the precedent not only for the United States, but for the world.”

The case was the first of its kind to reach trial. Seeley’s decision adds to a growing number of rulings that say governments have a responsibility to protect citizens from climate change. The timing of her verdict — coinciding with major wildfires and heatwaves that have taken lives worldwide — couldn’t be more poignant, said Julia Olson. She is the chief legal counsel and executive director of Our Children’s Trust, which has brought similar suits in all 50 states.

“As fires rage in the West, fueled by fossil fuel pollution, today’s ruling in Montana is a game-changer that marks a turning point in this generation’s efforts to save the planet from the devastating effects of human-caused climate chaos,” she said.

Climate change has profoundly shaped the lives of the 16 plaintiffs, both through psychological distress and the damage it has wrought to their homes and cultural heritage. Each has spoken eloquently about smelling wildfire smoke on the wind and feeling trapped by the increasingly oppressive heat of summer on the high plains. All of them have railed against state politicians for not only failing to mitigate the problem, but actively making it worse.

In their lawsuit, they argued that the state’s enthusiastic support of fossil fuels violates their inalienable right, enshrined in Article II of Montana’s constitution, to a “clean and healthful environment.” They also accused the governor and other officials of neglecting their constitutional duty to preserve and protect the environment for future generations. “Although defendants know that the youth plaintiffs are living under dangerous climatic conditions that create an unreasonable risk of harm, they continue to act affirmatively to exacerbate the climate crisis,” the suit states.

For two weeks in June, 12 of the plaintiffs poured their hearts out in a courtroom in Missoula. Their testimony was corroborated by a panel of climate scientists, childhood psychologists, and other experts who spoke to the impacts of a warming world and how it impacts young people.

“I know that climate change is a global issue, but Montana needs to take responsibility for our part,” 22-year-old Rikki Held, the lead plaintiff, testified. “You can’t just blow it off and do nothing about it.”

Seeley agreed. “Every additional ton of greenhouse gas emissions exacerbates Plaintiffs’ injuries and risks locking in irreversible climate injuries,” she wrote in her 108-page ruling. “Plaintiffs’ injuries will grow increasingly severe and irreversible without science-based actions to address climate change.”

The road to the trial was rocky, with the state attempting to throw the case out multiple times. During the trial the state attempted what some termed a “nothing-to-see-here” approach, bringing free-market economists and climate deniers to the fore to convince the judge that permitting and fossil-fuel regulation wasn’t really the state’s responsibility. The state also argued that even if it were to stop emitting CO2 entirely, it would have little impact.

Seeley didn’t buy that.

“Montana’s (greenhouse gas) emissions and climate change have been proven to be a substantial factor in causing climate impacts to Montana’s environment and harm and injury to the youth plaintiffs,” she wrote in her ruling. The judge also noted that the state did not offer a compelling argument for why it didn’t consider the impacts of greenhouse gas emissions when making permitting decisions. She also noted that renewable power is “technically feasible and economically beneficial.”

Emily Flower, spokesperson for state Attorney General Austin Knudsen, decried the ruling as “absurd” and called the trial a “taxpayer-funded publicity stunt.” She said the office plans to appeal.

“Montanans can’t be blamed for changing the climate,” Flower said, according to the Associated Press. “Their same legal theory has been thrown out of federal court and courts in more than a dozen states. It should have been here as well, but they found an ideological judge who bent over backward to allow the case to move forward and earn herself a spot in their next documentary.”

Attorneys who participated in the trial say that the verdict is notable because it puts the blame for inaction squarely on the shoulders of state officials, indicating they have the power to change their approach.

Seeley “recognized that the only obstacles to a transition to a clean energy economy in Montana are political,” said Melissa Hornbein, an attorney with the Western Environmental Law Center. “They’re not technological.”

Hornbein hopes the verdict shapes similar suits focusing on governmental responsibility for addressing climate change. Our Children’s Trust also represents 14 young plaintiffs in Hawaii in a similar case, Nawahine v. the Hawaiʻi Department of Transportation, which is now slated to move forward next year.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Montana youth win a historic climate case on Aug 14, 2023.

In the first half of 2023, households in the UK installed a record number of solar panels and heat pumps, according to MCS, the official standards body of the renewable technologies industry.

Installations for the two green energy sources were up 62 percent from the previous year, with an average of more than 17,000 households installing solar panels every month, reported Energy Live News and The Guardian.

Battery technology installations have grown each month, with more than 1,000 batteries installed in UK businesses and homes so far this year.

“In the spring, it was looking like we would have something like 215,000 MCS certified solar installations this year. But that was clearly an underestimate – I would bet on around 250,000 now,” said Gareth Simkins of Solar Energy UK, as The Independent reported. “Installing solar on your roof is one of the best home improvements you can make and more and more people realise the financial and environmental benefits.”

The UK government has a solar capacity target of 70 gigawatts (GW) by 2025. It also wants to install 600,000 heat pumps by 2028.

In the first half of this year, 17,920 heat pumps were installed, thanks to the availability of grants.

One of the biggest obstacles to increasing heat pump installations, according to MCS, is the number of skilled, qualified installers. It said that to meet the goal of 600,000 installations, 50,000 workers would be needed.

MCS said more than 850 new contractors have gotten their certification in 2023, which has already surpassed last year’s total.

“As the cost of energy continues to grow, we are seeing more people turn to renewable technology to generate their own energy and heat at home,” said MCS Chief Executive Ian Rippin, as reported by The Guardian. “We need to continue to push this expansion to meet our shared national ambitions to reach net zero by 2050. More consumers have the confidence to invest in small-scale renewables now than ever, but we have to make that transition even easier.”

Small-scale renewables installations in the UK currently have four GW of capacity, which is nearly twice that of the largest gas power plant in Europe, located near Pembroke, Wales.

“It is essential that the lowest-carbon heat becomes the lowest-cost heat, so that homeowners and landlords can justify the transition away from polluting fossil fuels,” said Bean Beanland, the director of external affairs at the Heat Pump Federation, as The Guardian reported. “If this is coupled to a genuine affordability and future funding package, then households will be able to contribute to climate change mitigation with confidence and at a cost that is fair to all.”

The post UK Homes Install Record Numbers of Heat Pumps and Solar Panels in First Half of 2023 appeared first on EcoWatch.

The wind picked up on Maui the night before the fires broke out. By early morning on August 8, gusts were whipping fast enough to topple trees and rip roofs off buildings in the historic Hawaiian town of Lahaina, on Maui’s west coast. Then came the conflagrations. Fanned by the blistering winds, flames hurtled as fast as one mile per minute as they engulfed Lahaina and other towns in Maui, like Kula, killed at least 96 people, and incinerated homes, businesses, and churches.

As thousands of displaced people take refuge in makeshift shelters and hotels, cadaver dogs and search crews are still trying to determine the true scope of damage from the deadliest wildfires in the United States in more than a century. Photos from Lahaina show harrowing scenes: rows of charred buildings behind the scorched shells of cars, consumed by fire as they sat in traffic; corpses of boats burnt on the water; a historic church reduced to rubble.

“Ultimately all the pictures that you will see will be easy to understand,” said Josh Green, Hawaiʻi’s governor, “because that level of destruction in a fire hurricane — something new to us in this age of global warming — was the ultimate reason so many people perished.”

Wildfires are not new to Hawaiʻi. According to the state’s wildfire management organization, roughly 0.5 percent of its total land catches fire every year, on par with other U.S. states. But conditions — many of them connected to climate change — have evolved to make parts of the state more likely to ignite. The blazes in Maui, for instance, were brought on by a “flash drought,” a major hurricane south of the archipelago, invasive weeds that acted like kindling,and winds that ran as high as 81 mph, according to the governor. There are allegations that Hawaiian Electric’s power lines played a role in the fire, too. The result: a wildfire even deadlier than the Camp Fire that incinerated the town of Paradise, California, killing 85 people, in 2018.

Though it’s too early to say exactly how climate change contributed to Maui’s wildfires, scientists have long been saying that similar disasters, like wildfires in the western United States, should be expected with more frequency and intensity on a warming planet.

Climate change is “leading to these unpredictable or unforeseen combinations that we’re seeing right now and that are fueling this extreme fire weather,” Kelsey Copes-Gerbitz, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of British Columbia’s faculty of forestry, told the Associated Press.

This summer, parts of Hawaiʻi experienced a “flash drought,” a rapid drying-out of soil and plants that occurs when hot air sucks moisture out of the ground. The drought left parts of Maui especially dry and ready to combust. Such droughts are likely exacerbated by climate change — although a longer-term trend of declining precipitation, which also contributed to the fires, may not be directly connected to human-caused climate change, a scientist told the Washington Post.

Compounding the drought, a proliferation of grasslands on abandoned plantations made vast fields into fuel for the fires. “There’s all these huge, huge quantities of vegetation and it’s all papery thin and ready to go,” Clay Trauernicht, a wildfire scientist at the University of Hawaiʻi, told Grist. As much as one-quarter of the state is covered by invasive grasses.

Adding to the drought and fields of tinder were exceptionally high winds, running from 60 to 81 miles per hour. Experts have said that the winds were fueled in part by Hurricane Dora, a Category 4 storm that barreled across the Pacific south of Hawaiʻi. Dora created a difference in air pressure across the archipelago that led to unusually fierce winds — the sort that plied roofs from buildings before driving flames across Maui.

As climate change makes hurricanes more intense, not all will make landfall, but they still could help spur deadly disasters. On Maui, where the fires did an estimated $5.6 billion of damage, according to the governor, the death toll is likely to climb for at least 10 more days, Green said. “They will find 10 to 20 people per day probably, until they finish,” he told CBS News. Hundreds of people are still missing.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How Maui’s wildfires became the country’s deadliest in more than a century on Aug 14, 2023.

According to Alain-Ricahrd Donwahi, the president of last year’s United Nations’ COP15 conference on desertification and a former defense minister from the Ivory Coast, it is likely that the planet will experience a major food supply disruption long before temperatures reach the threshold of 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

This is due to the effects of the climate crisis, along with inadequate farming practices and water shortages, posing threats to agriculture worldwide.

“Climate change is a pandemic that we need to fight quickly. See how fast the degradation of the climate is going – I think it’s going even faster than we predicted,” Donwahi said, as The Guardian reported. “Everyone is fixated on 1.5C , and it’s a very important target. But actually, some very bad things could happen, in terms of soil degradation, water scarcity and desertification, way before 1.5C.”

Donwahi went on to say that heat waves, intensifying flooding and droughts, as well as increasing temperatures were causing the possibility of food insecurity in many parts of the world.

“We could have an acceleration of negative effects, other than temperature,” Donwahi said, as reported by The Guardian. “When the soil is affected, the yield is affected.”

Donwahi said private investors needed to become involved in agriculture.

“The private sector has an interest in agriculture, and the better usage of the soil. We’re talking about [improving] yields. We’re talking about agroforestry, which is another way the private sector can have a return on investment. We have to be innovative, to find new vehicles for finance,” Donwahi said, as Green Queen reported.

Just 4.3 percent of climate finance goes to agriculture and food, but they make up almost one third of global greenhouse gas emissions, according to the Climate Policy Initiative (CPI).

“Climate finance for agrifood systems must increase at least sevenfold from current levels to reach the most conservative estimated needs for the climate transition, which is in the order of hundreds of billions of dollars annually,” CPI reported.

Additionally, less than one percent is directed to climate mitigation such as waste, food loss and low-carbon diets.

According to the first article in the United Nations Academic Impact series “Food Security and Climate Change,” food security is something the world needs to be thinking about now.

“In the next 30 years, food supply and food security will be severely threatened if little or no action is taken to address climate change and the food system’s vulnerability to climate change,” the article said.

In the United Kingdom, about half the food is imported, with a quarter of the imports from the Mediterranean, The Independent reported.

Recent heat waves, droughts, wildfires, intense rain and flooding have all led to crop damage in southern Europe.

“Shortages of salad and other vegetables in UK supermarkets in February this year caused by extremes in southern Spain and north Africa brought home to people just how vulnerable the UK is to the impacts of climate change on our food,” said Gareth Redmond-King, head of the international program at the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit, as reported by The Independent.

Donwahi said desertification is not something humans can ignore, as it affects everything from biodiversity to food security.

“Desertification and drought leads to climate change, leads to loss of biodiversity. And when you have climate change you have droughts, floods, storms,” Donwahi said, as The Guardian reported. “It’s not only the poor countries, everybody is in the same boat [on food security].”

The post Climate Crisis Likely to Cause Food Shortages Before We Reach 1.5°C Threshold, UN Expert Says appeared first on EcoWatch.

Every time we make a purchase we send messages to companies. Are you using your…

The post Precycling: Your Superpower that Makes a Sustainability Difference appeared first on Earth911.

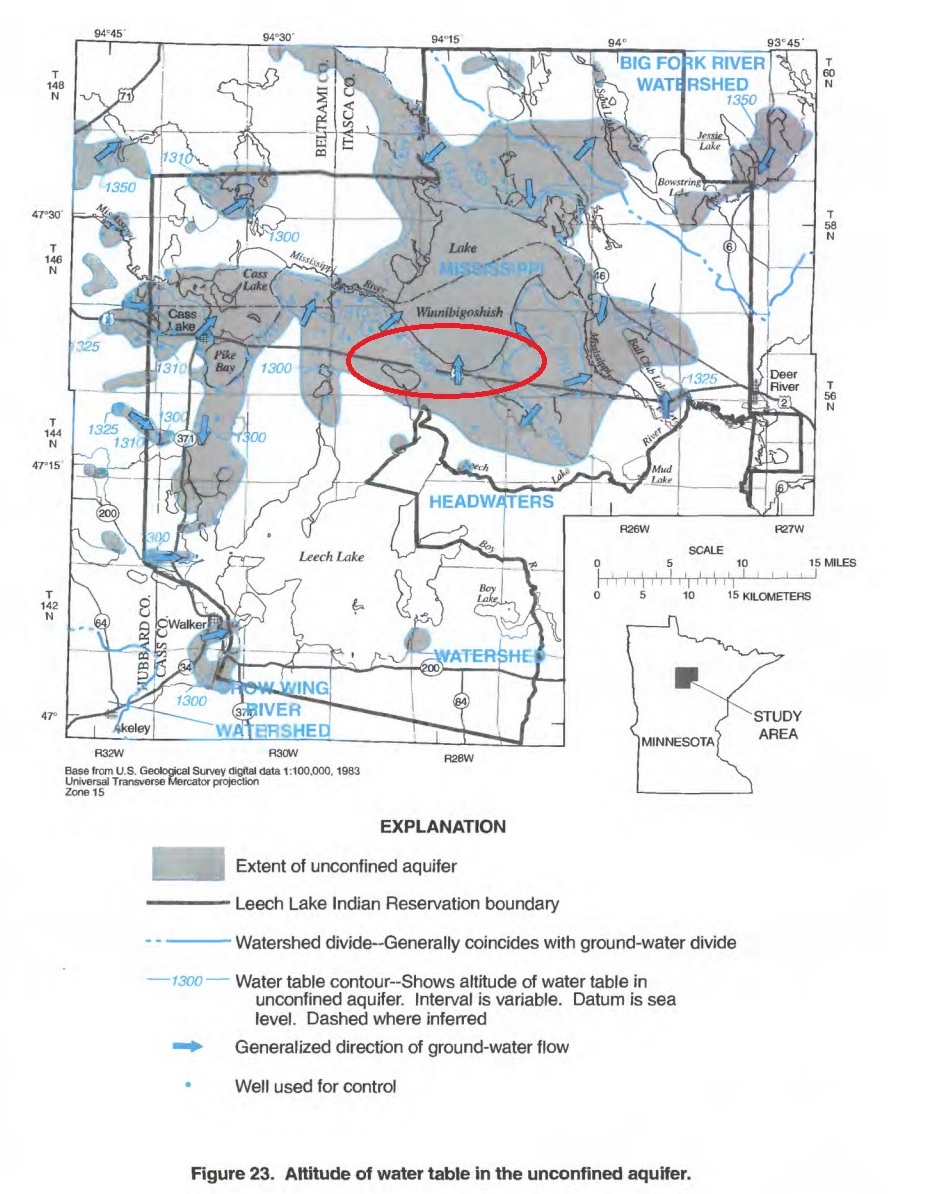

Laurie Harper, director of education for the Bug-O-Nay-Ge-Shig School, a K-12 tribal school on the Leech Lake Band Indian Reservation in north-central Minnesota, never thought that a class of chemicals called per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, would be an issue for her community. That’s partly because, up until a few months ago, she didn’t even know what PFAS were. “We’re in the middle of the Chippewa National Forest,” she said. “It’s definitely not something I had really clearly considered dealing with out here.”

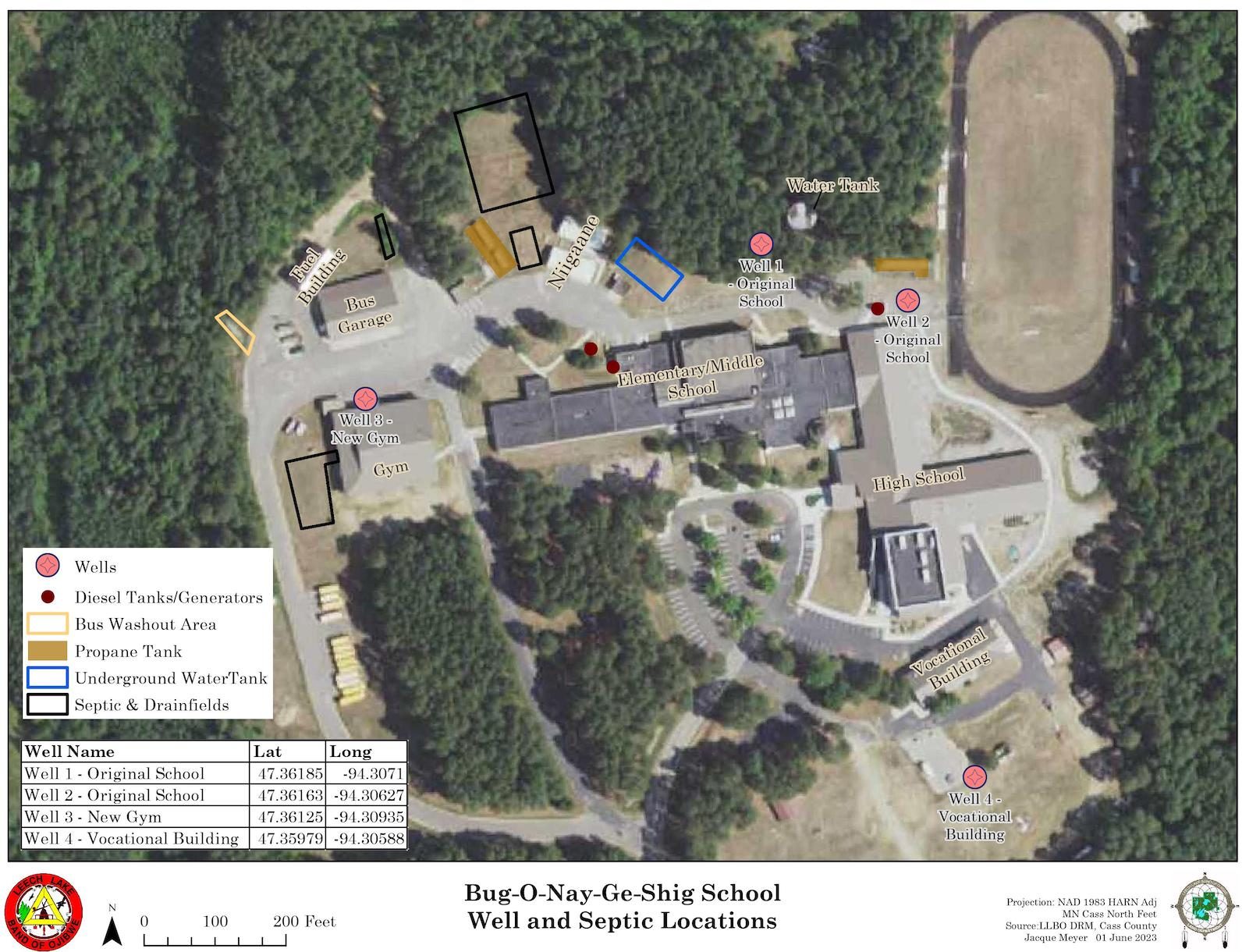

Late last year, tests conducted by the Environmental Protection Agency revealed that her school’s drinking water wells were contaminated with PFAS. Some of the wells had PFAS levels as high as 160 parts per trillion — 40 times higher than the 4 part-per-trillion threshold the federal government recently proposed as a maximum safe limit.

PFAS, also known as forever chemicals, are a global problem. The chemicals are in millions of products people use on a regular basis, including pizza boxes, seltzer cans, and contact lenses. They’re also a key ingredient in firefighting foams that have been sprayed into the environment at fire stations and military bases for decades. Over time, these persistent chemicals have migrated into drinking water supplies around the globe and, consequently, into people, where they have been shown to weaken immune systems and contribute to long-term illnesses like diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

After the EPA’s tests came back, Harper, who oversees education for the whole Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe, realized that some 300 students and faculty members at the Bug-O-Nay-Ge-Shig School had been consuming PFAS-tainted water for an indeterminate amount of time, perhaps since the school’s founding in 1975. Now, the chemicals are all Harper thinks about, and their presence in the school’s water supply is a constant reminder of a problem with no obvious solution.

“We can’t not provide education,” Harper said. “So how do we deal with this?” Months after discovering the contamination, she’s still looking for answers.

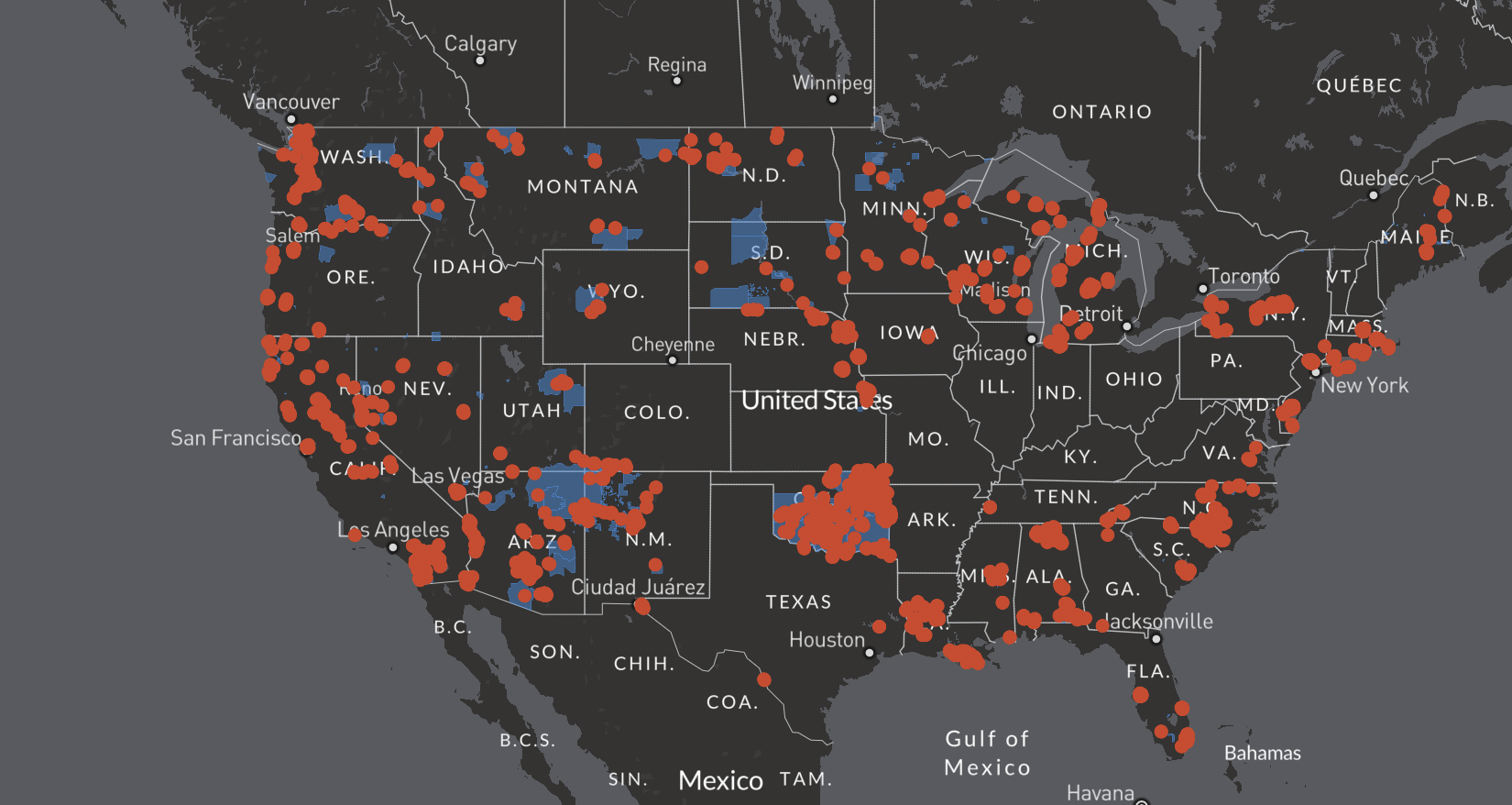

Beyond immediate concerns about how to get students clean water, the situation at the Bug-O-Nay-Ge-Shig School raises larger questions for Indigenous nations across the United States: Is Bug-O-Nay-Ge-Shig the only tribal school with PFAS contamination in its water? And how pervasive are PFAS on tribal lands in general? But data on PFAS contamination on tribal lands is patchy at best. In many parts of the country, there’s no data at all.

“There is very little testing going on in Indian Country to determine the extent of contamination from PFAS to drinking water systems, or even surface waters,” said Elaine Hale Wilson, project manager for the National Tribal Water Council, a tribal advocacy group housed at Northern Arizona University. “At this point, it’s still difficult to gauge the extent of the problem.”

PFAS have been around since the middle of the 20th century, but they’ve only been recognized as a serious health problem in the past decade or so after a lawyer sued DuPont, one of the top U.S. manufacturers of PFAS, for poisoning rural communities in West Virginia. Since then, a growing body of research has shed light on the scope of the PFAS contamination problem in the United States — nearly half the nation’s water supply is laced with the chemicals — and water utilities are finally taking stock of what it will take to remediate the contamination. But for the 547 tribal nations in the U.S., there is nothing resembling a comprehensive assessment of PFAS contamination. Tribal water systems have gone largely untested because many of them are too small to meet the EPA’s PFAS testing parameters.

“We can certainly say that PFAS is an issue for every single person in the United States and its territories, that includes tribal areas,” Kimberly Garrett, a PFAS researcher at Northeastern University whose work has highlighted the lack of PFAS testing on tribes.

The federal government has a responsibility to protect the welfare of all Americans, but it has a legal obligation to tribes. In the 18th century, the government entered into some 400 treaties with Indigenous nations. Tribes reserved specific homelands, or were forcibly moved to places designated by the government, and guaranteed rights like fishing and hunting, as well as peace and protection. Experts say that responsibility to tribes includes protection from contaminants.

“Every treaty that assigns land to tribes impliedly guarantees that land as a homeland for the tribes,” said Matthew Fletcher, a law professor at the University of Michigan and a member of the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians. “Contaminated land is a breach of that treaty land guarantee.”

If PFAS are as widespread on tribal lands as they are in the rest of the U.S., many reservations likely have a public health emergency on their hands. They just don’t know it yet.

In some ways, Bug-O-Nay-Ge-Shig, known as the Bug School, got lucky. In December last year, the Environmental Protection Agency, armed with funding supplied by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law passed by Congress in 2021, approached Leech Lake leaders to ask if the tribe would like to have its water tested for PFAS. The agency had $2 billion to help small or disadvantaged communities test their water supplies for emerging contaminants. The Bug School qualified as both.

When the tests came back positive, the school immediately started shipping in 5-gallon jugs of drinking water and the cafeteria started using bottled water to prepare meals. The school even paused a community gardening program meant to teach students about the value of fresh foods out of fear that the soil was contaminated.

The school knew that it had a contamination problem on its hands, but believed that the problem would be temporary — the measures it put in place were Band-Aids until a long-term solution was found. Months into the crisis, however, school administrators have yet to figure out a permanent fix. The school still doesn’t know where the contamination is coming from, and the cost of cleaning the chemicals out of its water supply threatens to be prohibitively expensive.

PFAS remediation requires equipment, frequent testing, and dedicated personnel who have the capacity to monitor forever chemicals for years. Paying for PFAS cleanup is a tall order in large, affluent communities with the resources to address toxic contaminants. The mid-sized city of Stuar, Florida, discovered PFAS in its water supply in 2016 and, to date, has spent more than $20 million fixing the problem. The PFAS in their water still aren’t entirely gone.

On reservations, figuring out who’s responsible for testing for PFAS and paying for remediation is an impossible puzzle to crack, mainly because no one seems to know where the buck stops.

Federal PFAS testing has largely bypassed tribal public water systems. That’s because tribal systems are smaller, on average, than non-tribal public water systems. Every five years, the EPA tests the nation’s drinking water for “unregulated contaminants” — chemicals and viruses that are not regulated by the agency but pose a potential health threat to the public. The EPA finally included PFAS in its testing for unregulated contaminants in 2012, alongside a list of metals, hormones, and viruses. But it mainly tested systems that serve more than 10,000 people.

A study conducted by Northeastern University found that just 28 percent of the population served by tribal public water systems was covered by that round of PFAS testing, compared to 79 percent of the population served by non-tribal water systems. There were also no PFAS results for approximately 18 percent of the tribal water systems tested by the EPA “due to missing data or lack of sampling for PFAS,” the study said. To make matters more complicated, many Indigenous communities get their water from private wells, which are not monitored by the EPA. A recent study suggests a quarter of rural drinking water, much of which comes from private wells, is contaminated by PFAS.

Data on PFAS in tribal areas, experts emphasized over and over again, is extremely scarce. “We don’t know if PFAS is disproportionately affecting tribal areas,” Garrett said. “We won’t know that until we get more data.”

What limited data exists is outdated. The Environmental Working Group, an advocacy organization that tracks PFAS contamination across the U.S., conducted a rough, preliminary PFAS estimate on tribal lands in 2021 using what data there was available at the time. It showed that there are nearly 3,000 PFAS contamination sites, like garbage dumps, within five-miles of tribal lands. The analysis is almost certainly an underestimate.

The lack of PFAS testing on tribal lands is compounded by the fact that there is no one entity responsible for testing and treating tribal water systems for PFAS. That’s partly due to the fact that PFAS are a relatively new issue, but it also has a lot to do with the lack of centralized monitoring of tribal health in general. For example, American Indian and Alaska Native communities experienced some of the highest COVID-19 infection rates in the United States in 2020. But the siloed nature of tribal, local, state, and federal data collection systems means that no one has a real sense of just how many Indigenous people died in the pandemic, even years after the crisis began.

If history is any indication, Fletcher, the law professor, said, remediating these contaminants will be a game of push and pull between the federal government and tribes. In previous efforts to rid reservations of arsenic and lead contamination, he said, “usually the fights are the tribe insisting that the government do something and the government doing everything it can to avoid any kind of liability or obligation.”

In the 1990s, Rebecca Jim, a Cherokee activist and former teacher who was instrumental in raising awareness about lead poisoning among children in Ottawa County, Oklahoma, had to navigate a complicated patchwork of tribal governments, federal bureaus, and treaties to finally get the government to clean up the Tar Creek Superfund site on the Quapaw Nation — one of the agencies largest Superfunds. It took a decade for Jim and other activists to pressure the EPA into cleaning lead — the legacy of mining for materials used in bullets — out of Ottawa County, and she maintains that the EPA only started paying attention to what was happening in Tar Creek after a local masters student discovered that approximately one-third of children in a town in the county called Picher had lead poisoning.

“There’s always a fight,” Jim said. “It’s all about money and where you’re going to get the money to do the work.”

Jim said that testing for contaminants on tribal lands is generally the responsibility of the Indian Health Service, an agency housed within the National Institutes of Health, or falls to a given tribes’ own environmental protection office. But it becomes the EPA’s problem once the agency designates an area as a Superfund site, like Tar Creek was. Then, the EPA tries to go after the polluters responsible for the mess in the first place. If the agency is successful, Jim explained, there is generally ample funding for cleanup efforts. If a polluter can’t be pinned, it falls on the EPA to fund the cleanup, which is a more laborious and less thorough process because there’s fewer dollars to go around. And if the contamination occurs at a federally-controlled tribal school, like the Bug School, the Bureau of Indian Education is responsible. It’s a veritable maze of jurisdiction — even finding where you are in the maze is a tall order.

Laurie Harper’s efforts to untangle the bureaucratic knot that governs decision-making and testing for contaminants at the Bug School may serve as a lesson to other tribal schools that discover PFAS contamination in their water supplies. In February, two months after the EPA approached the school to offer PFAS testing, the results came back. The agency called the school immediately and said it needed to shut down its water system, an urgent request that caught administrators off guard. “We were still like, what? OK, how long is this going to last? Do we open the water? What do we do with it?” Harper said.

In March, desperate for answers, Harper traveled to Washington, D.C., and met with the director of the Bureau of Indian Education, or BIE, Tony Dearman, who heard her concerns about finding a long-term solution for the school.

What she didn’t find out until later, however, was that the BIE had already conducted its own testing at the Bug School in November 2022, during what Harper and other school administrators had assumed was just the agency’s annual compliance check. “They were already aware that the Bug-O-Nay-Ge-Shig school had tested high for PFAS,” Harper said. “They didn’t tell the school administration nor did they tell the tribe. They didn’t even tell the EPA.”

Unbeknownst to her, the BIE had sent a very short email to the school months earlier, in February, telling them that the bureau had found levels of two types of PFAS — PFOA and PFOS — in the school’s water. When Harper finally tracked down that letter and read it, she was appalled by how vague the language was.

“We have received the PFAS (specifically, Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS)) results from the November 2, 2022 sampling event,” it read. “There were several exceedances of PFOA at Wells 1, 2, 3 and 4 and PFOS detection at Well 3 all were above the State limit for and EPA Health Advisory for PFOA and PFOS, please see attached spreadsheet.” The letter did not define what PFAS were or how dangerous they can be to human health. And it certainly did not make it clear to Bug School administrators that the school was in the midst of a public health crisis. “I’m an educator, not a hydrologist,” Dan McKeon, the school’s superintendent and the primary recipient of the letter. “There was notice of results that exceeded some standards, but no guidance about what that meant or what we should do.”

The BIE concluded the letter by telling the school that it would be conducting a second round of PFAS testing within 30 days to “confirm the analytical results” of its initial tests and then determine next steps, but the bureau didn’t return for testing until April 2023 — more than five months after the initial test, and weeks after Harper’s meeting with director Dearman. BIE, she was told by the bureau’s own leadership, was putting out fires on multiple fronts. “You’re not the only school that’s testing high for PFAS,” she recalls BIE’s supervisory environmental specialist telling her.

In a written response to questions from Grist, a spokesperson for the BIE said the bureau is “committed to providing schools with safe drinking water” that meets federal standards and that it is in the process of collecting water samples from BIE-owned public water systems at 69 schools. The bureau did not respond to questions from Grist about how many tribal schools exceed the EPA’s newly proposed 4-part-per-trillion PFAS limit.

In the past few years, Harper told Grist that two people who worked at the Bug School have died from cancer. Multiple female employees have thyroid issues. Harper knows that these diagnoses could be linked to hereditary, behavioral, or environmental exposures. But the deaths — the most recent, a man who died from testicular cancer just a year ago — have made solving the school’s PFAS situation feel even more urgent. Harper has been meeting with EPA, BIE, BIA, and state agencies to get the problem solved. “I’m so frustrated with how bureaucracy works,” she said. But she’s in the fight for the long haul, whatever it takes. “It’s the long-term solutions we’re interested in, not just the quick fix.”

Harper isn’t working in a vacuum; 2023 has been a breakthrough year for PFAS awareness and remediation nationwide. Earlier this summer, major manufacturers of PFAS, including Dupont and 3M, agreed to multi-billion-dollar settlements with cities and states across the country — the largest PFAS settlements thus far. At the end of July, the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, a tribe located about 115 miles southeast of the Bug School, filed a companion lawsuit, tied to those earlier settlements, against 3M for the cost of gathering data on PFAS, treating its drinking water supplies, fisheries, and soil for contamination, and monitoring the health of the tribe.

The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, a state agency that monitors environmental quality, has conducted a preliminary investigation into the PFAS contamination at the Bug School after school administrators alerted the agency to the problem, but that probe didn’t reveal what the source was. The agency said it will conduct another, “in-depth investigation involving soil and groundwater sampling” at the Bug school in the fall.

Also at the state level in Minnesota, a bill introduced in the legislature this year would permit Minnesotans who are exposed to toxic chemicals to sue the companies responsible for producing the chemicals and force those companies to pay for the cost of screening for conditions that are caused by exposure. 3M has fought these kinds of laws as they’ve cropped up in state legislatures because a legal right to seek medical monitoring will likely lead to a situation in which the company will have to pay billions of dollars’ worth of medical bills. But Harper is sure she can drum up support for the legislation. “I know I can convince other tribes to get behind a law that would allow medical monitoring in the state of Minnesota,” she said. “This is our land. These are our children. These are our families.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline What one school’s fight to eliminate PFAS says about Indian Country’s forever chemical problem on Aug 14, 2023.