Tag: Environmental Awareness

Greenland’s Ice Sheet Surface Melt Is Accelerating While Antarctica’s Slows Down, Study Finds

According to a new study by researchers at the Netherlands’ Utrecht University and the University of California, Irvine (UCI), the rate at which Greenland’s surface ice has been melting has increased in recent decades, while surface ice melt in Antarctica has slowed.

For the study, the researchers examined the role that katabatic and Foehn winds — downslope gusts that bring dry, warm air rushing to the tops of glaciers — play in the melting of Greenland’s ice sheet. They said that, in the past decade, melting related to the winds has increased more than 10 percent in Greenland, but their impact on Antarctica’s ice sheet has gone down by 32 percent.

“We used regional climate model simulations to study ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica, and the results showed that downslope winds are responsible for a significant amount of surface melt of the ice sheets in both regions,” said co-author of the study Charlie Zender, UCI professor of Earth system science, in the press release. “Surface melt leads to runoff and ice shelf hydrofracture that increase freshwater flow to oceans – causing sea level rise.”

The study, “Wind-Associated Melt Trends and Contrasts Between the Greenland and Antarctic Ice Sheets,” was published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Though the winds’ impact was substantial, Zender said the earmarks of global warming were having contrasting influences in the Southern and Northern hemispheres.

Surface melt due to the wind was being exacerbated by Greenland “becoming so warm that sunlight alone (without wind) is enough to melt it,” Zender said.

Warmer surface air temperatures, along with the 10 percent increase in melt driven by the wind, have resulted in 34 percent more total surface ice melt. Zender attributes this partially to global warming’s influence on the index differential of sea level pressure, the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO).

NAO’s shift to a positive phase led to below-normal high latitude pressure, which brought warm air to Greenland and other areas in the Arctic.

On the other hand, since 2000, Antarctica has seen a decrease in total surface melt of about 15 percent. The reduction is due in great part to the Antarctic Peninsula having 32 percent less wind-generated downslope melt in the same area where two ice shelves collapsed.

Zender pointed out that the ozone hole in the Antarctic stratosphere, discovered in the 1980s, is still recovering, providing the surface with temporary insulation from additional melt.

“The ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica keep over 200 feet of water out of the ocean, and their melt has raised global sea level by about three-quarters of an inch since 1992,” Zender said in the press release. “Although Greenland has been the No. 1 driver of sea level rise in recent decades, Antarctica is close behind and catching up and will eventually dominate sea level rise. So it’s important to monitor and model melt as both ice sheets deteriorate, including the ways climate change alters the relationship between wind and ice.”

The post Greenland’s Ice Sheet Surface Melt Is Accelerating While Antarctica’s Slows Down, Study Finds appeared first on EcoWatch.

Sea Level Rise Will Affect 4 Out of 5 Miami Residents, Even Those Living Outside of Flood Zones, Study Says

Sea-level rise due to climate change is becoming an increasing concern for island nations and low-lying areas, such as Miami-Dade County, Florida.

The primary focus of research on sea-level rise has been the direct effects of flooding, but a new study also considers socioeconomic vulnerabilities.

The study found that, in the coming decades, four out of five Miami-Dade County residents could face displacement or disruption due to sea-level rise, whether or not they live in a flood zone, a press release from the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia Climate School said.

The researchers concluded that, as inundation increases, lower-income residents will bear the brunt of a lack of habitable areas and skyrocketing housing prices. A small percentage of affluent residents will have the means to move from waterfront or low-lying properties, but others may have no choice but to stay, according to the study.

“Most studies focus on the direct effects of inundation,” said Nadia Seeteram, lead author of the study and a postdoctoral researcher at Columbia’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, in the press release. “Here, we were able to look at flooding on a very granular level, and add in other vulnerabilities.”

The study, “Modes of climate mobility under sea-level rise,” was published in the journal Environmental Research Letters.

The researchers looked at a combination of rainfall, storm surge and projections of flooding caused directly by sea-level rise that went from building to building, as well as demographic data, in determining the effects on residents, the press release said.

The team used data from the U.S. Census Bureau along with flood maps to chart the social and economic factors that would lead to residents being more or less vulnerable. These included age, income, employment status, race, education level, whether they were homeowners or renters and other factors.

The population was then divided into four categories. The first and most common were those residents facing sea-level rise of one meter, considered a “middle-of-the-road” possibility by the year 2100. This scenario would affect 56 percent of residents who live mostly on higher ground. The researchers called this portion of the population “displaced,” saying they could be faced with pressure to relocate.

The next most common group — 19 percent — were those living in perpetually flooded areas without the means to move to higher ground. The research team called this portion of the population “trapped.”

Another 19 percent of residents were those considered “stable” because they lived in areas that weren’t prone to flooding and were able to stay.

The wealthiest percentage of the population, the seven percent the team called “migrating,” would be subjected to flooding in low-lying or waterfront areas, but would be able to relocate to safer metro area locations.

“However, social and economic risks may extend to communities substantially beyond flooded areas as the spatiotemporal dynamics of flood risks are realized through housing markets, insurance and risk-transfer mechanisms, and adaptation investments,” the study said. “Notably ‘climate gentrification’ and affordable housing shortages can result from increasing demand for housing in safer areas. Furthermore, disaster-related displacement and declining property values and household wealth from [sea-level rise] and extreme flooding have the potential to exacerbate existing social inequity.”

The research team said that beyond a meter of sea-level rise would mean direct flooding, rather than economic pressures, would become the main factor affecting the population.

Two meters — a “fairly high” estimate — would cause inundation for more than half the population from more rainfall and sea-level rise. This would lead to 49 percent of residents becoming trapped and a quarter displaced. Just eight percent would be classed as stable.

“This is where it gets to be more drastic, more existential,” Seeteram said in the press release.

Seeteram said both scenarios would mean the potential for depopulation and devaluation of flooded properties. This could make it harder for tax collection by authorities to fund infrastructure adaptation to hold back flood waters.

Flooding is already a routine occurrence in the area, as rain collects in the streets and high tides come up through sewers. Seeteram said during the wet season from May to October, flash flooding is common.

Signs of climate gentrification have already begun, with property values and development in a neighborhood 10 lofty feet above sea level called Little Haiti soaring. The predominantly Black residents of the neighborhood fear they may be forced to move.

“I suspect it is already happening,” said co-author of the study Katharine Mach, who is University of Miami’s chair of the Department of Environmental Science and Policy, in the press release.

Mach said other factors may be more responsible for changing real-estate values at the moment, such as already established pro-development policies.

“The question is, what fraction [of rising prices] can you put on climate?” Mach said.

Mach added that waterfront and low-lying areas are seeing increased real-estate prices, while locations less prone to flooding aren’t going up as quickly, which may indicate that buyers’ decisions are being affected by predicted rises in sea levels.

Seteeram said the study’s projections might not happen, but it depends on how the city deals with these issues in the future. The effects of sea-level rise could be tempered with measures like infrastructure modification.

“We could see different kinds of housing development, to make the population denser in some areas, or more climate resilient. But then you would have to see what the intersection would be with affordability for a lot of people,” Seteeram said in the press release.

The post Sea Level Rise Will Affect 4 Out of 5 Miami Residents, Even Those Living Outside of Flood Zones, Study Says appeared first on EcoWatch.

Invasive Species 101: Everything You Need to Know

Quick Key Facts

- An invasive species is a living thing that, typically because of human activity, has gained a foothold in a new part of the world and is causing negative ecological or economic impacts.

- The term “invasive species” has become contentious among some observers because of concerns with how the subject intersects with climate change, colonialism, nativist ideology and parsing out unharmful, non-native species with harmful ones.

- Non-native species can be harmful if they outcompete native species, consume excess numbers of prey species that haven’t adapted to ward them off, destroy ecosystems, introduce new diseases or cause economic harm.

- Burmese pythons and some carp species were intentionally introduced to the U.S. and have since wreaked havoc in their new ecosystems, in part because of their ability to outcompete existing predators and consume large numbers of prey species that don’t have defense mechanisms against them.

- Some invasive species, like spotted lanternflies, are considered to be more of a threat to agricultural and economic activities than ecological wellness.

- In the U.S., some communities and organizations eradicate invasive wildlife by hunting and eating them. Invasive plants are uprooted through targeted removal campaigns or events.

What Are Invasive Species?

Whether an animal, a plant or a microbe, an invasive species generally describes a living thing that has not historically lived in a given region. An invasive species by definition has a decidedly negative ecological or economic impact on the habitat it has entered, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. That could be because it lacks natural predators in the area, so it eats a lot of prey that other native predators in the ecosystem rely on. Or perhaps it crowds out other species for space or necessary resources, killing off a vital crop that regional farmers sell.

An invasive species, as described by the USDA, is one that was likely spread by human activity — not one that naturally migrated or adapted to a new area.

Why Is The Term ‘Invasive Species’ Controversial?

While some non-native species have a devastating effect once they are introduced to an ecosystem, and thus rise to the definition of invasive species, most do not. And not everyone agrees as to whether we should be classifying any species as “invasive” at all.

That controversy lies in part with the definition of what is native or not. Centuries of European colonization and exploration brought new species, intentionally or otherwise, to new lands. Plants and animals that feel distinctly, inextricably American — like apple trees and house cats, for example — were brought to what is now the United States, but attempts to remove or eradicate those from the country would likely face backlash.

Plus, as the climate changes, the related environmental impacts will influence where species are able to survive. Temperature bands are already shifting, forcing creatures to migrate into new territory they otherwise may not have ventured into if conditions in their former habitat were still amenable to them. That makes it tricky to categorize what is or isn’t a native species, which could result in whether conservation measures are taken in that species’ favor as the climate crisis continues. Because of this and other forces pushing wildlife out of their current territory span

Another concern expressed by experts is that the focus on the purity of native species and ecosystems echoes nativist thinking and racial purity ideologies, according to Vox.

Meera Iona Inglis, a professor of animal and environmental ethics at Newcastle University, argued in a 2020 paper that “we should discard the term ‘invasive species’ and instead use the term ‘potential problem species’ to describe species which appear to be causing harm in a given time and place,” noting that part of her philosophy stems from the “parallels between the portrayal of animal and human immigrants as dangerous invaders.”

Why Are Some Invasive Species Harmful?

Non-native species have the potential to harm native wildlife and plant species by outcompeting them for critical resources like prey and habitat or by overly consuming them in the case of prey species without suitable defense mechanisms. Although natural selection means that species can’t just survive or thrive unless they have evolved to earn a niche in their ecosystem, invasive species may have traits that give them a major evolutionary advantage over species in the native ecosystem. That would put native species at a severe disadvantage, considering they likely couldn’t evolve or adapt quickly enough to ward off the threat. And if an invasive species is able to both outcompete native predators and eat more than their share of species that are lower on the food chain, they could reduce the biodiversity of an area with relative speed.

Other invasive species may end up destroying the ecosystem itself. The emerald ash borer, a type of beetle that likely came from Asia via wood packing material, has killed hundreds of millions of ash trees across North America as its larvae eat the trees’ inner bark, according to the Emerald Ash Borer Network, which is affiliated with Michigan State University.

The threat of invasive species also can look like the importation of diseases that native species aren’t equipped to fend off. According to the National Wildlife Federation, one type of introduced elm bark beetles is an efficient vector of Dutch elm disease, which since 1930 has spread through these beetles “from Ohio through most of the country, killing over half of the elm trees in the northern United States.”

Are Invasive Species Ever Beneficial?

By definition, invasive species aren’t beneficial to an introduced ecosystem. But again, non-native species aren’t necessarily harmful — meaning they have the potential to be beneficial within new ecosystems. Some non-native trees provide shelter for local pollinators or migrating birds, while some non-native wildlife can increase the amount of food available for native predators, according to The New York Times. And a 2022 study in the journal Science noted that when populations of native, seed-dispersing species are threatened, non-native species can help to disperse seeds instead.

How are Invasive Species Impacting American Ecosystems?

The United States Geological Survey, an agency of the U.S. Department of the Interior that conducts invasive species research, notes that “more than 6,500 nonindigenous species are now established in the United States,” although that number is not necessarily the number of invasive species, i.e., potentially harmful species. Here are five that are known to be causing harm in ecosystems in the U.S. to which they have been introduced.

Burmese Pythons

Burmese pythons are native to several Asian countries, including India, China and Malaysia. But during an explosion of the U.S. exotic pet trade in the 1980s, according to the History Channel, Burmese pythons were imported for pets, often destined for South Florida homes — but the 20-foot-long snakes don’t make good pets and were often dumped by their owners once they became difficult to keep.

Those snakes soon reproduced in the swamps across the region. Without native predators, the Burmese python has been tied to the decimation of many native species of mammals, birds and reptiles. Attributing the decline to the growth of the Burmese python, the U.S. Geological Survey notes that “raccoons [have] dropped 99.3%, opossums 98.9%, and bobcats 87.5% since 1997” in the southern portions of the Everglades National Park.

“While pythons will eat common native species and nonnative species such as Norway rats, they can also consume threatened or endangered native species,” including endangered Key Largo wood rats, explains the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

Certain Carp Species

Several species of carp are considered invasive, including bighead, black, grass and silver carps, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. The fish were intentionally introduced in the 1970s to the U.S. to help control algae blooms and for human consumption, but the agency explains that the fish “escaped confinement and spread to the waters of the Mississippi River basin and other large rivers like the Missouri and Illinois.

Now, the invasive carp populations have exploded, reducing the amount of food and habitat available for aquatic species native to the area — which in turn makes it harder for commercial and recreational fishers to catch what they want.

“As filter feeders, [different invasive carp species] consume the base of the aquatic food chain, starving out and outcompeting native fish species,” explains the National Wildlife Federation on their website. “Additionally, silver carp become a safety hazard to boaters and anglers on waters they inhabit, leaping feet out of the air and weighing up to 40 pounds.”

Spotted Lanternflies

Originally from China, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service says that the spotted lanternfly was first found in the U.S. in 2014 and has since spread to 14 states. Currently considered to be more of an agricultural threat than an ecological one, spotted lanternflies are known to feed on fruiting trees, including apples, cherries, peaches, plums and walnut trees, as well as other crops like grapes and hops.

Water Hyacinths

Water hyacinths — a leafy, aquatic plant with light purple flowers — were introduced for ornamental purposes in the U.S. in the late 1880s from South America’s Amazon Basin. But according to the National Invasive Species Information Center, the freshwater plant also “forms dense colonies that block sunlight and crowd out native species.” The University of Florida’s Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants finds that this blanketing effect makes human water activities “impossible” once they move into an area. The water hyacinth has made its way across two-thirds of the U.S., but Florida has been able to keep the plant’s abundance under control.

How Do Invasive Species Hurt Economic Activities?

Invasive species aren’t just an ecological concern; they can also cause strong economic problems. Spotted lanternflies, for example, threaten Pennsylvania’s grape, apple and stone fruit industries, as well as its pine and hardwood logging sector. Those industries account for billions of dollars of sales and economic activities in the state, according to the Invasive Species Centre, based in Canada.

Another example can be found in the case of the zebra mussel. Originally from the Black and Caspian seas, the zebra mussel has proliferated across the Great Lakes region, according to the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies. In addition to its voracious appetite for critical prey species — namely, plankton and microzooplankton — that threatens or endangers native mussel and other aquatic species, the zebra mussel attaches en masse to water intake pipes and industrial equipment, causing damage.

How Can I Reduce The Impact of Invasive Species?

Preventing species that are known to harm local ecosystems from entering the region is key to reducing their harm. The U.S. Department of Agriculture notes that invasive species can hitch a ride to new destinations on imported cargo and commercial shipments, in addition to passenger vehicles, in addition to ocean containers, aircraft, rail cars and commercial trucks. Checking personal vehicles and clothing for plants, seeds or wildlife before traveling between regions can help reduce invasive species contamination.

Once a harmful non-native species appears in a new area, there are different ways that nonprofits, governmental agencies, communities and even commercial entities opt to eradicate before the creature can cause problems or further existing concerns. In areas where lionfish have become invasive, for example, hunting competitions are held to catch and kill them for both sport and for consumption. Whole Foods even sells lionfish in some of its stores, noting on its website that the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch considers the fish to be a “best choice” for consumption because of their invasive species status. And spotted lanternflies have been the subject of informational campaigns encouraging people to squish them on sight.

Some observers of the invasive species conundrum debate the ethics of culling creatures because of their potential for injurious behavior in their introduced habitat. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, or PETA, has condemned decapitation that is allowed during contests to kill an invasive python species. However, the organization doesn’t necessarily believe that all invasive species should be allowed to remain in the introduced environment, proclaiming that house cats should never be allowed outside because of their outsized impact on native wildlife.

In places where invasive plant species have begun to take root, volunteer events are sometimes held to teach community members which species are harmful and should be removed, as well as how to safely dispose of them. To find such events in your community, reach out to local extension schools, nature clubs or environmental agencies to understand what the options are — or use an internet search engine to seek out “invasive species removal projects in” your area.

The post Invasive Species 101: Everything You Need to Know appeared first on EcoWatch.

Scientists lay out a sweeping roadmap for transitioning the US off fossil fuels

Meeting the Biden administration’s goal for the United States to be a net-zero greenhouse gas emitter by 2050 is a monumental challenge that must be tackled at an even more daunting pace. But the nation’s top scientists envisioned that future and laid out a plan for realizing it in a report released on Tuesday.

In a sweeping 637-page document, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine made 80 recommendations for how the United States can justly and equitably pursue decarbonization policies. It includes recommendations for everything from establishing a carbon tax to phasing out subsidies for high-emissions animal agriculture and codifying environmental justice goals.

“This report addresses how the nation can best overcome the barriers that will slow or prevent a just energy transition,” said Stephen Pacala, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at Princeton University and chair of the committee that authored the latest findings, which build on an earlier report released in 2021. He added that only about a quarter of the recommendations require congressional action, with many being targets at private institutions and federal agencies. There is also a recognition that some changes are unlikely to happen immediately.

“Do we think Congress will go out and pass this? No,” he said. “But maybe a future Congress will.”

The hope is that these recommendations can eventually help further solidify the impacts that legislation such as last year’s Inflation Reduction Act and the 2021 bipartisan infrastructure law are expected to have.

“Congress has invested a fair amount of our money in this transformation … but the committee sees multiple hurdles that impair the effectiveness of those starting funds,” said Ed Rightor, another author of the report and the former director of the Center for Clean Energy Innovation at the Information and Technology and Innovation Foundation. For example, it found that “perhaps the single greatest risk to a successful energy transition during the 2020s is the risk that the nation fails to site, modernize, and build out the electrical grid.”

Authors call on policymakers to alleviate such roadblocks with steps like reforms to the permitting process that would accelerate the building of transmission lines, as well as expand existing programs such as the weatherization-assistance program that helps people make their homes more energy-efficient. They also call for broader changes to the United States’ approach to combating climate change, including establishing a national greenhouse gas emissions budget.

None of these ideas are necessarily new, said Jamal Lewis, a state and local policy director for the electrification nonprofit Rewiring America. But he says the comprehensive approach makes for a particularly robust roadmap, and the National Academies could lend weight to policy pushes that are already in progress.

“The National Academies is a highly respected and authoritative voice,” said Lewis, adding that he liked that the authors looked at decarbonizing across different sectors of the economy. “All of these actions do, and need to, work together to help us achieve our climate goals.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Scientists lay out a sweeping roadmap for transitioning the US off fossil fuels on Oct 17, 2023.

We Earthlings: Do an Octopus a Favor

There are many reasons to not eat some foods, and the intelligence of the animal…

The post We Earthlings: Do an Octopus a Favor appeared first on Earth911.

Is the Miyawaki Method the Answer to Deforestation?

Despite major efforts like the European Union’s new law to prevent deforestation, forests are disappearing…

The post Is the Miyawaki Method the Answer to Deforestation? appeared first on Earth911.

How a little-known pollution rule keeps the air dirty for millions of Americans

This story was originally published by the The California Newsroom, a collaboration of public radio stations, NPR, and CalMatters; the nonprofit newsroom MuckRock; and the Guardian. It is republished under a Creative Commons (BY-ND 4.0) license.

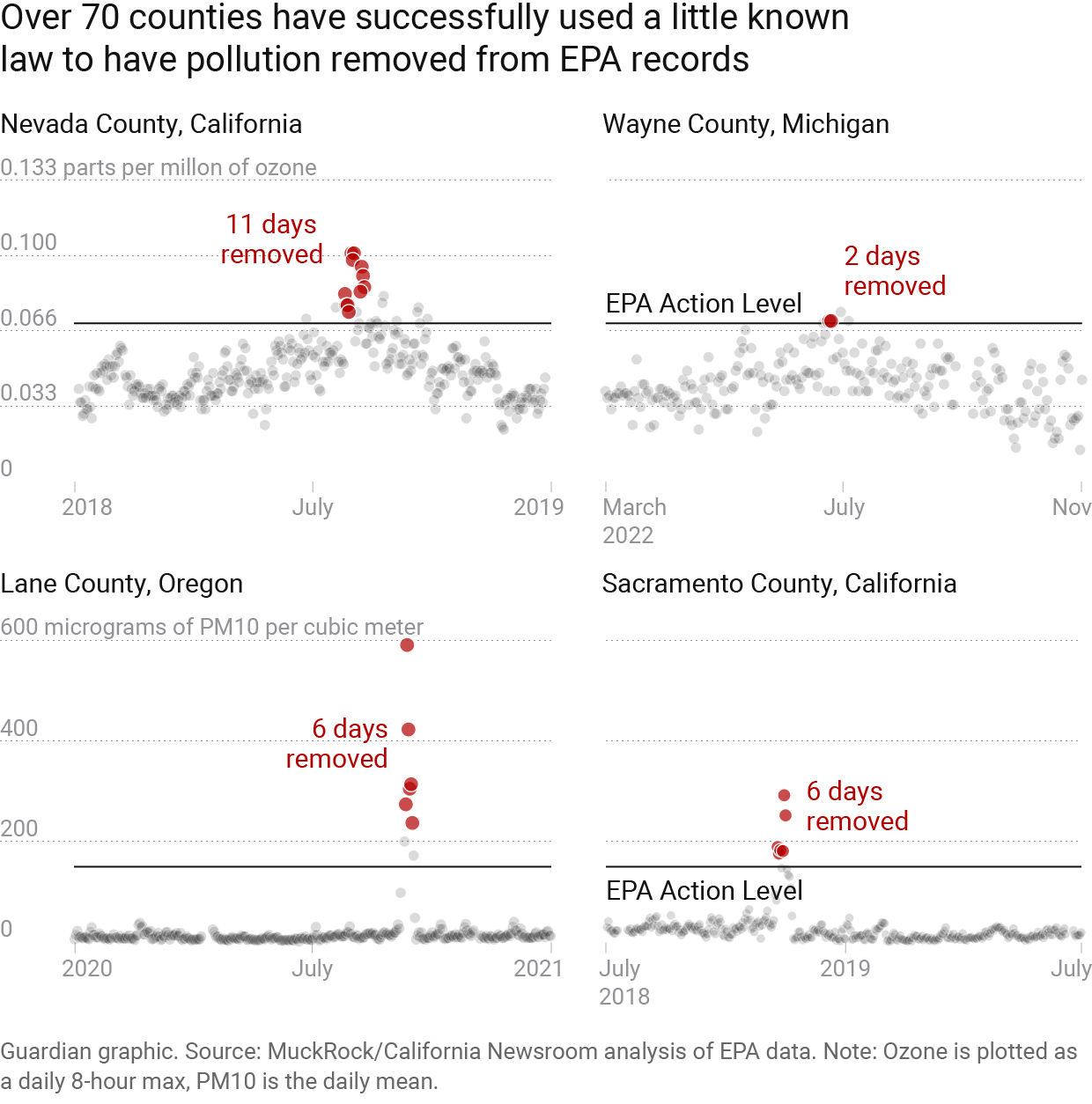

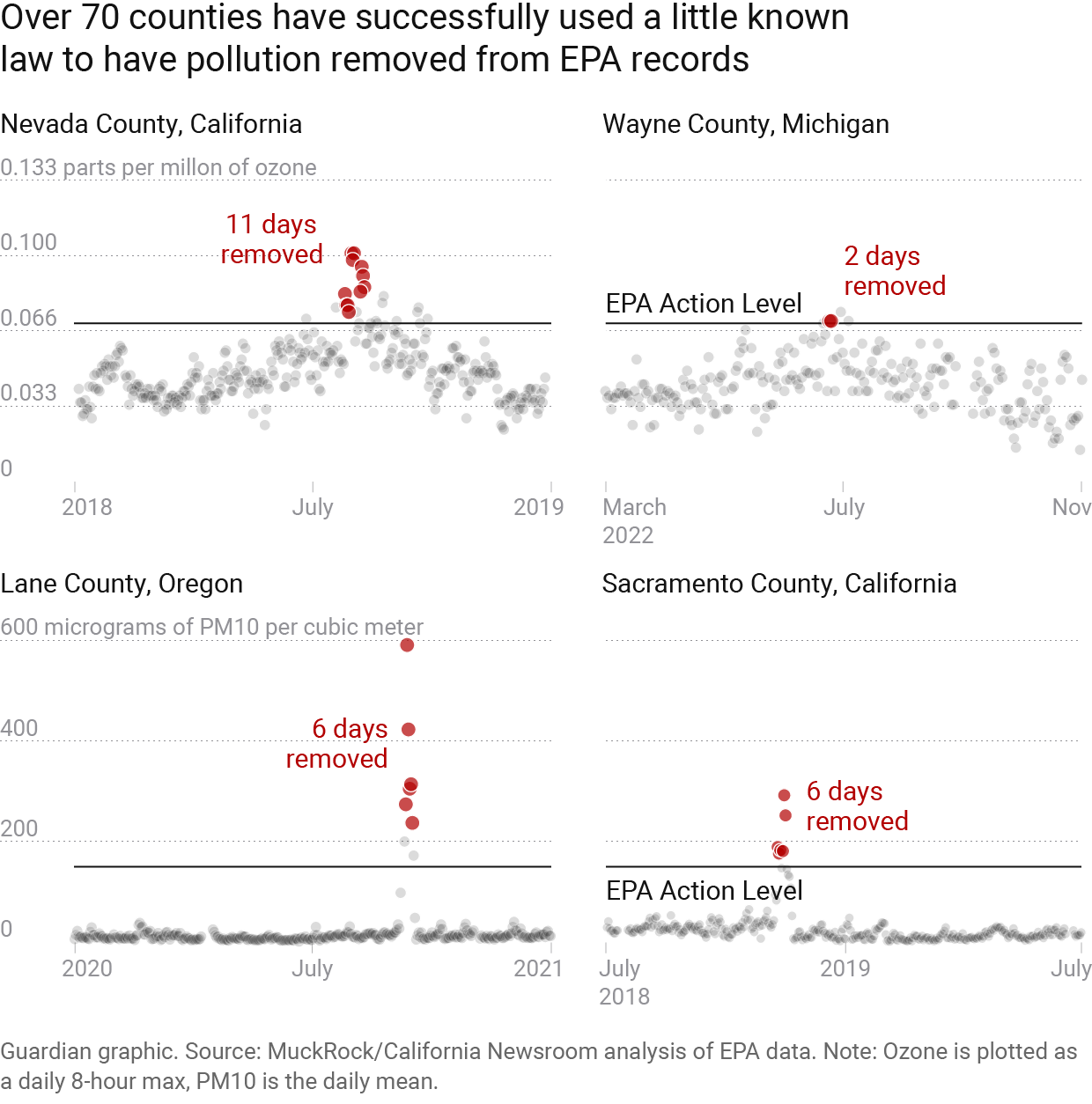

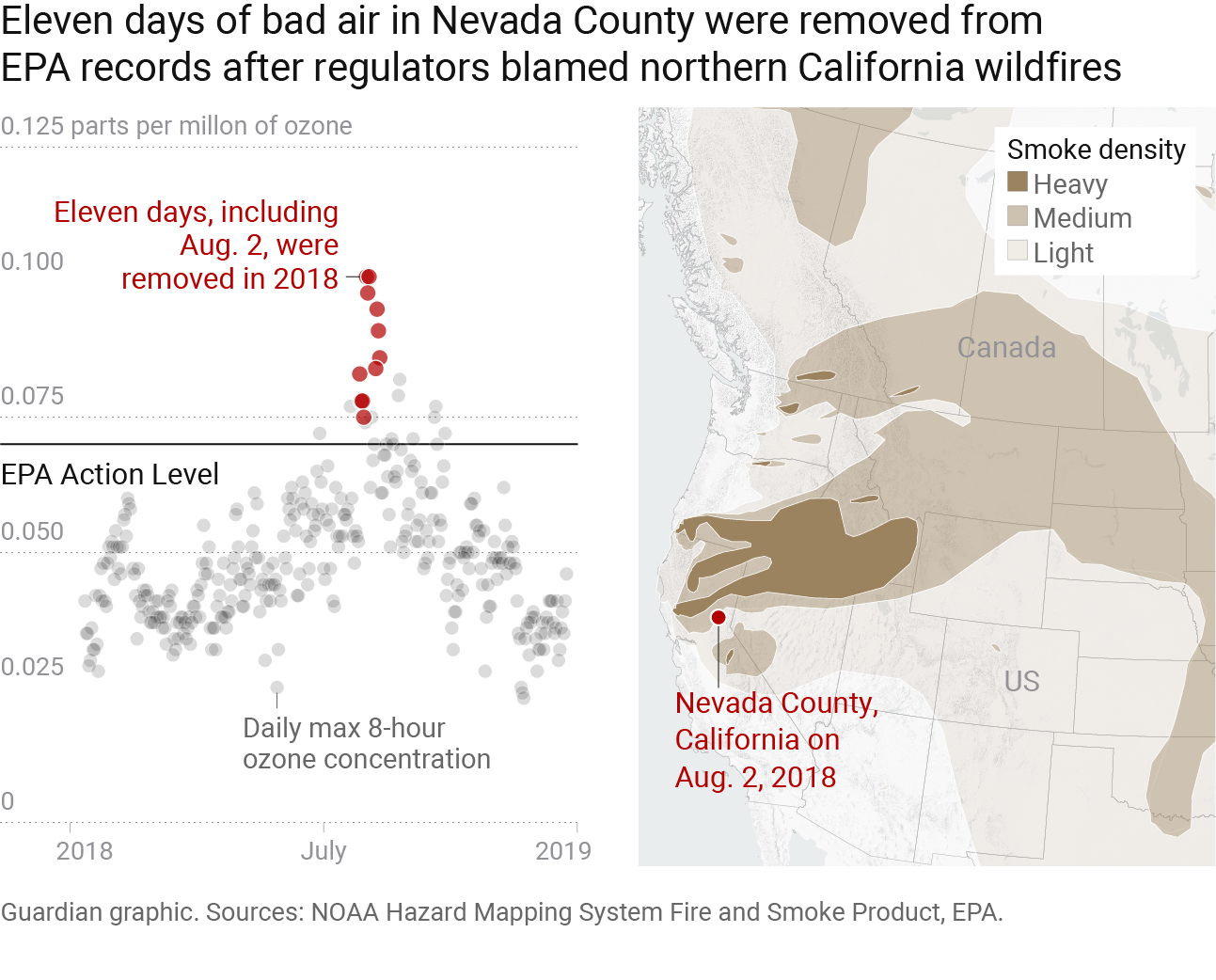

A legal loophole has allowed the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to strike pollution from clean air tallies in more than 70 counties, enabling local regulators to claim the air was cleaner than it really was for more than 21 million Americans.

Regulators have exploited a little-known provision in the Clean Air Act called the “exceptional events rule” to forgive pollution caused by “natural” or “uncontrollable” events – including wildfires – on records used by the EPA for regulatory decisions, a new investigation from The California Newsroom, MuckRock and the Guardian reveals.

In addition to obscuring the true health risks of pollution and swerving away from tighter control on local polluters, the rule threatens the potency of the Clean Air Act, experts argue, at a time when the climate crisis is posing an unprecedented challenge to the health of millions of Americans.

Where the EPA — the U.S. department monitoring air quality — has agreed to exclude bad air days from analysis, “we may have a sort of stable, relatively rosy picture when it comes to our regulatory world in terms of air-quality trends,” said Vijay Limaye, a climate and health epidemiologist at the Natural Resources Defense Council, a nonprofit advocacy group.

The truth is more complicated, and the air dirtier.

“The true conditions on the ground in terms of the air that people are breathing in, day after day, week after week, year after year, is increasingly an unhealthy situation,” Limaye said.

For the summer of 2023, more than 20 states so far, from Wyoming to Wisconsin to North Carolina, have flagged air-quality readings that were far higher than normal. Most of these days came in June, as skies in the midwest and eastern US were blanketed with Canadian wildfire smoke.

We pored over thousands of pages of regulatory documentation, correspondence and contracts, and analyzed hard-to-find public data to better understand how local regulators make use of the exceptional events rule, as global heating sparks extreme wildfires more often.

We found that, since 2016, when the EPA last revised the guidance on exceptional events, local regulators in 21 states filed requests with the agency to forgive pollution and, in 20 of those states, had them approved.

In total, local regulators made note of almost 700 exceptional events. The EPA agreed to adjust the data on 139 of them. The adjustments came in more than 70 counties across 20 states. The affected areas stretched from the forested Oregon coast to the Ohio Rust Belt, from the craggy Rhode Island coastline down to the bayous of Louisiana.

In more than half of the states where exceptional events were forgiven, industry lobbyists and business interests pressed to make that happen, sometimes as the only public voice in the regulatory process. Also, to protect the status quo, some regulators spent millions of taxpayer dollars doing research for and making exceptional events requests, sometimes working hand in hand with industry stakeholders.

Andri Tambunan/The Guardian

Meeting air-quality standards matters a lot to industry and politicians. Violations can add up to stricter, more costly and potentially unpopular pollution controls.

Critics say the growing use of the exceptional events rule for wildfires is of deep concern. “You need to level with the public about the number of days when the air quality was unhealthy,” said Eric Schaeffer, a former regulator who directs the Environmental Integrity Project.

“We have saved more lives in this country because we cleaned up the air than almost any other environmental policy,” said Michael Wara, the director of the climate and energy policy program at Stanford’s Woods Institute for the Environment. “And that’s what’s being undermined.”

“The world has changed,” he said. “We are living in a different world when it comes to wildfire and all of its consequences, including air pollution.”

In response to written questions, the EPA said it takes all air pollution seriously.

“Wildland fire and smoke pose increasing challenges and human health impacts in communities all around the country,” Khanya Brann, an EPA spokesperson, wrote. “EPA works closely with other federal agencies, state and local health departments, tribal nations, and other partners to provide information, tools, and resources to support communities in preparing for, responding to, and reducing health impacts from wildland fire and smoke.”

The EPA also pointed to “mitigation plans”, in which air districts that have experienced repeated exceptional events must create plans for educating and notifying the public about the pollution risk, as well as “steps to identify, study, and implement mitigating measures” like limiting use of wood-burning stoves and wetting down unpaved roads before dust storms.

More ‘toxic soup’ and more paperwork

In the U.S., clean-air policy long allowed local governments to write off some wildfire smoke on a case-by-case-basis as “unrealistic to control” or “impractical to fully control”. But in 2005, the Republican senator Jim Inhofe of Oklahoma, who has long denied the climate crisis, won a years-long battle to amend the Clean Air Act. The new rule gave local officials more opportunity to exclude pollution from regulatory consideration for an array of events, from fireworks displays and volcanic eruptions to wildfires and even unusual traffic events.

At first, the rule was used most successfully in a handful of south-western communities where high winds created a recurring problem of dust pollution. Over time, local regulators have turned to exceptional events for wildfires more and more often to reach air-quality goals.

Andri Tambunan/The Guardian

Our analysis of local and EPA records found that in 2016, air agencies flagged 19 wildfire events as potential exceptional events. In 2018 and 2021, 52 and 50 wildfire events were flagged. In 2020, 65 were.

“The uptick in exceptional events is absolutely consistent with what we see in the air pollution data,” said Marshall Burke, an associate professor of global environmental policy at the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability. Smoke is accounting for a higher proportion of overall air pollution, and it’s going up quickly, Burke said — not just in the western U.S., but nationwide.

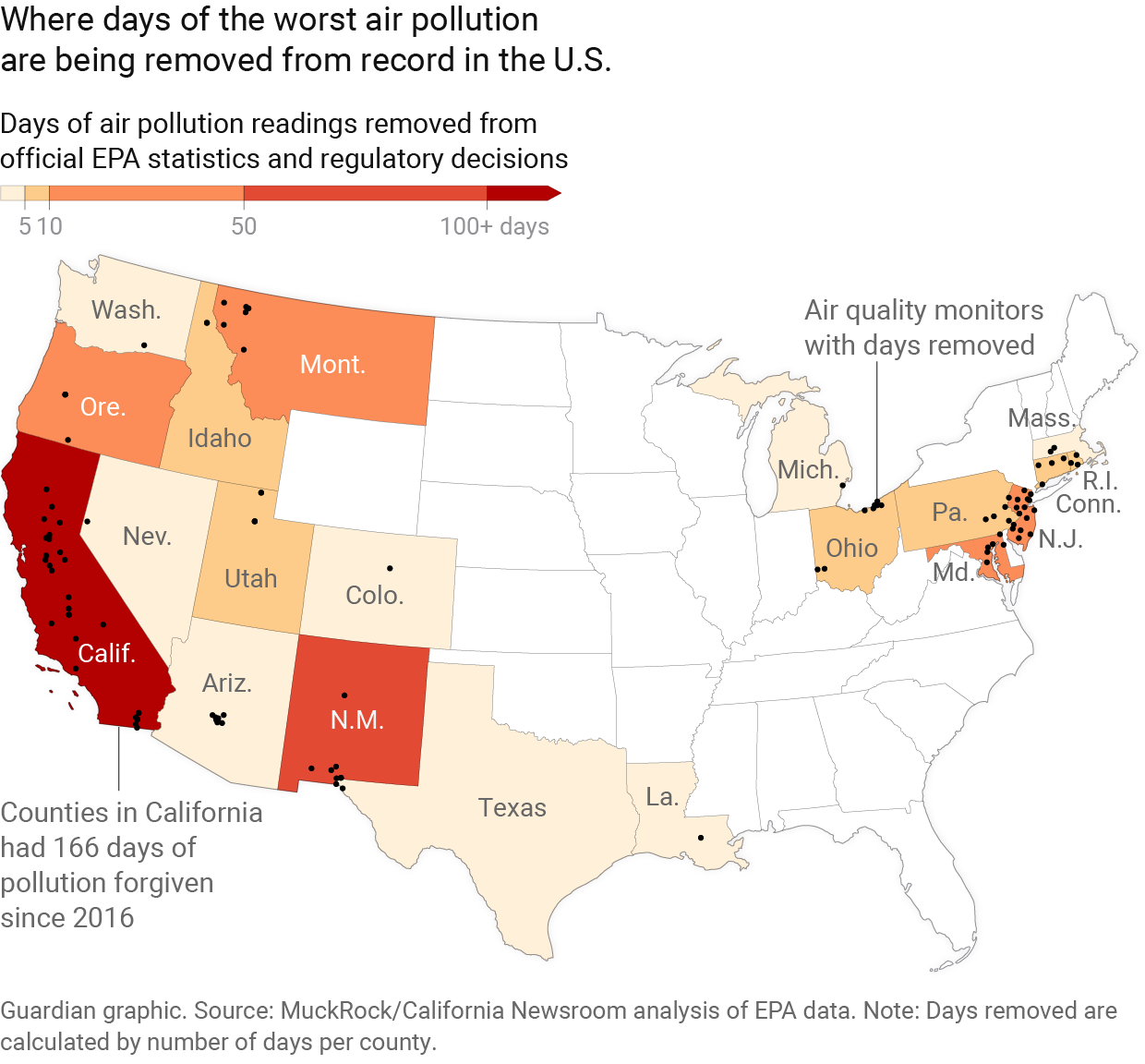

No state is blamed more for smoke pollution than California, followed by Oregon and Canadian provinces, according to our analysis. Western states are more likely to point fingers at each other, while states in the midwest and north-east place the blame on Canadian provinces like Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Wildfire smoke is a dirty and complicated polluter. Limaye, of the NRDC, called it a “toxic soup of air pollution.” It carries soot and ash, regulated as particulate pollution, as well as hydrocarbons and other gases that, cooked in sunlight, help form ground-level ozone. It’s a growing concern for public health, both near the source and thousands of miles away. Smoke, especially from a long-burning fire, can travel long distances and linger at dangerous levels for weeks at a time.

We analyzed data recorded at air monitors nationwide. For every U.S. county, on a day where the EPA excluded any data, we counted that day. Our analysis found that the total number of wildfire-related bad air days erased from regulatory consideration in counties nationwide was nearly double that of bad air days related to high winds: 236 compared to 121.

When wildfire caused air pollution, the rule was applied to more monitor readings over multiple days, not just to exclude particulate pollution but also smog or ozone.

“It is a lot of time,” said John Walke, a lawyer for the NRDC.

One or two violations at a single air monitor can flip an area from meeting air standards to missing the mark, according to Walke. Three or four violations over several years can prompt increasingly strict local pollution controls. “So a lot is riding on one, or two, or three violations,” he said.

A smokier future

The recent experience of California’s Nevada County may offer a glimpse of a smokier future. So far, the exceptional events rule has removed 16 days from the record there in the last five years.

Andri Tambunan/The Guardian

Ozone levels are rising in the background in this foothill community, according to Julie Hunter, the interim chief for the Northern Sierra Air Quality Management dDstrict. She said more trucks and warmer temperatures are to blame. More frequently now, she said, wildfire smoke is like a “pancake,” settling flat across the rural valley, stuck until conditions change.

During one fire in 2021, a thick plume of smoke covered the sun in the town of Grass Valley. “We couldn’t see past down the driveway,” said Dr. Alinea Stevens, the medical director at the Chapa-De Indian Health clinic in town.

Stevens remembered doctors and nurses moving among patients under the menacing amber skies, N95 masks snug on their faces to protect against Covid-19 — and wildfire smoke.

Over hours, the clinic’s security guards got lightheaded and developed headaches. “We told them, you need to wear N95 masks, too,” Stevens said. “That kind of prolonged exposure to those things was very real.”

After fires in 2018 and 2020, the EPA wiped more than two weeks of ozone pollution in the district from the record. That didn’t get Nevada County all the way to a clean bill of health, but local regulators avoided having to tighten rules on local emissions. Hunter, the local regulator, said her district is likely to seek more exceptional events there, including for fires in the last two years.

“If we take out wildfire smoke as one of the things that we look at, then we’re not going to be addressing problems that really affect our community here,” said Stevens, who directs the health clinic. The surge of asthma and other health problems from smoke can be overlooked when it happens in a rural community, she said: “I think it’s maybe a way that we don’t put enough attention into fixing something that can be fixed.”

Officials at the California Air Resources Board stress that state law works toward mitigating the effects of climate change, and state policies are supposed to minimize the risk of catastrophic fire.

“We really are trying to pull out all the stops,” Michael Benjamin, the chief of CARB’s air-quality planning and science division, said. Practically, he added: “We and the air districts in California will continue to take advantage of the exceptional events provisions in the Clean Air Act to try to show attainment.”

Brian Feinzimer/LAist

When it comes to showing attainment, the stakes are high.

Scrubbing smoke from regulatory accounting allows local governments and business to continue as usual, since the practice obscures the toll wildfires take on public health.

It also ignores the ways that the climate crisis is altering how people decide where to live across the U.S.

‘We are all inheriting this’

In 2017, Maitreyi Siruguri and her husband woke in the night to a sky lit unnaturally orange. They left their Santa Rosa home with their young children in the early hours of the morning; the fire that eventually swirled through went on to kill 22 people and destroy more than 5,600 structures.

Afterward, “I was starting to sense the emotional drain, from everyone having to go through this,” she said. She searched the internet with worry about how smoke could harm her children, then three and seven years old.

In 2021, they left for the suburbs of Chicago. They could afford to buy a house; the family would be closer to friends and relatives — and further, she hoped, from wildfire and smoke.

Growing up in India in the 1980s and 1990s, and working as a climate educator, Siruguri knows very well that there is no escape hatch leading away from environmental problems. “We are all inheriting this, in every part of the world,” she said.

Wara, of Stanford’s Woods Institute, argues that such an inheritance requires investment. Rather than trying to protect the status quo, he said, governments could make a new cost-benefit analysis.

Andri Tambunan/The Guardian

“It would not be unreasonable” to boost spending significantly to manage public and private lands to minimize smoke, “something like what we think is reasonable when it comes to coal-fired power plants, which is billions of dollars per year”, he said. “Because the harms that are being created by the smoke are large.”

This summer, as air quality worsened across Illinois from Canadian fires, Siruguri worried anew in Naperville. On a late July day, when smoke pollution had returned, she brought her child to soccer camp, and asked the camp’s director whether the air was healthy.

He didn’t have an answer. “He was like, well, we kind of wait till somebody tells us what to do or you make the decision for your child,” she said.

Siruguri believes the government must work to stop climate change, including by switching energy sources away from fossil fuels. She believes that when officials talk to the public, they should be honest about how smoke is changing air over time.

“It’s hard for the general public to know. The next time I see bad air quality, I will be looking for how that’s getting recorded,” Siruguri said. “It is concerning that these decisions are made behind the scenes, almost.”

Walke of the NRDC agreed: “The worst possible outcome is lying to the American people about whether the air they breathe is safe or unsafe.”

Smoke, Screened: The Clean Air Act’s Dirty Secret is a collaboration of The California Newsroom, MuckRock and the Guardian. Molly Peterson is a reporter for The California Newsroom. Dillon Bergin is a data reporter for MuckRock. Emily Zentner is a data reporter for The California Newsroom. Andrew Witherspoon is a data reporter for the Guardian.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How a little-known pollution rule keeps the air dirty for millions of Americans on Oct 17, 2023.

Rivers Can Take Years to Recover From Drought, Research Finds

Drought is usually associated with lack of rainfall, but there are other factors, like snowmelt and groundwater, that can affect the water levels of streams and rivers.

In a new study, researchers from University of California, Riverside (UCR), found that drought impact can persist for as long as three-and-a-half years in rivers and streams despite precipitation from a series of storms, a press release from UCR said.

The total water level of streams is measured by two factors: total water level, affected by rainfall and snowmelt, and baseflow, the share fed by groundwater.

“People often just use rain as an indicator of drought because it’s easier to measure. But there are other kinds of drought that each have their own impacts,” said Hoori Ajami, the study’s corresponding author and associate professor of groundwater hydrology at UCR. “We needed a new way to see how long it takes for one form of drought to become another form.”

Baseflow droughts are studied by fewer researchers, and there had not previously been an accurate measurement technique for them. Since lack of baseflow significantly impacts ecosystem services, as well as water management, the researchers chose to turn their focus on this important aspect of hydrology.

The study, “Comprehensive assessment of baseflow responses to long-term meteorological droughts across the United States,” was published in the Journal of Hydrology.

The category of drought that affects rivers and streams is called hydrological drought, to which baseflow belongs. Baseflow impacts water availability for drinking, bathing and irrigation. It affects plants, wildlife and the overall health of ecosystems. Infrastructure stability could also be impacted by severe hydrological drought.

In order to develop a method for defining the start and end points of hydrological droughts in specific locations, the researchers looked at three decades’ worth of data from 350-plus locations around the U.S.

The research team only looked at baseflow on rivers and streams that did not have any dams or reservoirs and had not been impacted by human activity.

The results showed that a hydrological drought’s beginning and end is dependent on a variety of factors, including a location’s geography and typical climate.

A wide array of lag times were found between the end of a drought due to lack of rainfall and the conclusion of a baseflow drought. For instance, streams in parts of Kansas took 41 months to recover, but those in Pasadena’s Arroyo Seco area took nearly a year.

“When we are looking at water management strategies, it is clear we cannot implement a one-size-fits-all solution everywhere, for every stream. Our approaches need to be site specific,” said lead author of the study Sanghyun Lee, who is now a postdoctoral fellow with the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service in Oklahoma, in the press release. “When I first came to California in 2016, people asked me, ‘Is the drought over?’ They wanted to know if our watersheds had recovered. This new study shows it may take another few years until they get back to normal.”

The team’s results were consistent with earlier studies finding that water recovery in underground aquifers also experiences a delay in responding to lack of rainfall. Aquifers are an important water source for agriculture, as well as rivers’ baseflow.

Too much pumping of groundwater during drought could lead to sinkholes, which can cause shifts or even the collapse of buildings and other types of infrastructure.

“One key message we want to send is that people must be careful about managing the water they have,” Lee said in the press release. “Because of rising temperatures, baseflow drought is getting longer and more severe in many parts of the country. And because watershed boundaries often cross state or international lines, preserving precious water resources will require more cooperation.”

The post Rivers Can Take Years to Recover From Drought, Research Finds appeared first on EcoWatch.

Solar-Powered Car Completes 620-Mile Test Drive Across North Africa

Solar is a major contributor to the renewable energy mix, with everything from solar lights and heating to solar TVs and refrigerators.

Now, there is the Stella Terra, the first off-road solar-powered car, which recently completed a test drive of 620 miles across north Africa without recharging.

“We are pushing the boundaries of technology. With Stella Terra, we want to demonstrate that the transition to a sustainable future offers reasons for optimism and encourages individuals and companies to accelerate the energy transition,” said Wisse Bos, team manager of Solar Team Eindhoven, in a press release from Eindhoven University of Technology.

Students from Eindhoven University of Technology designed the two-seater, which crossed a variety of landscapes during the test, reported The Guardian.

“Stella Terra must withstand the harsh conditions of off-roading while remaining efficient and light enough to be powered by the sun. That is why we had to design almost everything for Stella Terra ourselves, from the suspension to the inverters for the solar panels,” Bos said in the press release.

The moss green vehicle is powered entirely by solar panels on its rounded roof, which means it can run even in remote areas where there are no electric vehicle (EV) charging stations. It is also designed to drive on multiple surfaces so that it can be used for emergency deliveries and services, said the team’s events manager Thieme Bosman, according to CNN.

“Morocco has a huge variety of landscapes and different surfaces in quite a short distance,” Bosman said, and the car was tested “on every type of surface that a car like this could encounter.”

With a top speed of 90 miles per hour, the solar car’s battery has a range of about 441 miles on regular roads and 342 miles off-road on a sunny day. When the sun is obscured by clouds, the Stella Terra could have a range of about 31 miles or even less.

“It was an incredible trip with a positive ending. Stella Terra’s efficiency was hard to predict. That’s why we weren’t sure if we would make it on solar power. During the ride, Stella Terra turned out to use 30 percent less energy than expected. We were able to drive the entire trip on the sun’s energy and did not depend on charging stations,” Bos said in another press release from Eindhoven University of Technology.

Bos said the solar vehicle is a decade ahead of any other car on the market, The Guardian reported.

“We are pushing the boundaries of technology,” Bos said.

Stella Terra comes with a rechargeable lithium-ion battery so it can run over shorter distances on less sunny days. Its solar panels also provide enough electricity for phone and camera chargers and cooking devices.

After initial steering system issues, the car did well in its road tests from Tangier, Morocco, through Fes to the Sahara Desert.

“We hope this can be an inspiration to car manufacturers such as Land Rover and BMW to make it a more sustainable industry. The car was actually very comfortable in the off-road conditions as it is very light and does not get stuck,” said Bob van Ginkel, the project’s technical manager, according to The Guardian.

The car’s solar panel converter had 97 percent efficiency in turning absorbed sunlight through the photovoltaic cells into electrical charge.

The weight of Stella Terra is about a quarter of an average midsize SUV, which requires larger and heavier batteries to power them than standard EVs, reported CNN.

“(One of) the benefits of the solar panels on top is that we can have a much smaller battery because we are charging while driving,” said van Ginkel.

The car also has “lightweight and robust” materials to reduce its weight, as well as an aerodynamic design that lessens drag.

Solar Team Eindhoven previously produced a campervan, and Stella Terra includes elements of its design. The car has seats that fully recline into a bed, and its solar panels extend to both maximize its charging capabilities and create an awning to provide shade.

One of the biggest challenges in building vehicles that run on solar power is that surface area for the solar panels is limited. Production of the highly efficient solar panels capable of generating enough power for long distances is expensive.

Sponsors provided funding for the not-for-profit team that designed Stella Terra. Van Hulst said more work needed to be done on the design before it would be ready to be put on the market.

“We aim to also inspire not only everyday people, but also the automotive industry, the Ford and Chryslers of the world, to think again about their designs and to innovate faster than they currently do,” Bosman said, as CNN reported. “It’s up to the market now, who have the resources and the power to make this change and the switch to more sustainable vehicles.”

The post Solar-Powered Car Completes 620-Mile Test Drive Across North Africa appeared first on EcoWatch.