This story was originally published by ProPublica, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for Dispatches, a newsletter that spotlights wrongdoing around the country.

In the 1950s, after quarreling for decades over the Colorado River, Arizona, and California turned to the U.S. Supreme Court for a final resolution on the water that both states sought to sustain their postwar booms.

The case, Arizona v. California, also offered Native American tribes a rare opportunity to claim their share of the river. But they were forced to rely on the U.S. Department of Justice for legal representation.

A lawyer named T.F. Neighbors, who was special assistant to the U.S. attorney general, foresaw the likely outcome if the federal government failed to assert tribes’ claims to the river: States would consume the water and block tribes from ever acquiring their full share.

In 1953, as Neighbors helped prepare the department’s legal strategy, he wrote in a memo to the assistant attorney general, “When an economy has grown up premised upon the use of Indian waters, the Indians are confronted with the virtual impossibility of having awarded to them the waters of which they had been illegally deprived.”

As the case dragged on, it became clear the largest tribe in the region, the Navajo Nation, would get no water from the proceedings. A lawyer for the tribe, Norman Littell, wrote then-Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy in 1961, warning of the dire future he saw if that were the outcome. “This grave loss to the tribe will preclude future development of the reservation and otherwise prevent the beneficial development of the reservation intended by the Congress,” Littell wrote.

Both warnings, only recently rediscovered, proved prescient. States successfully opposed most tribes’ attempts to have their water rights recognized through the landmark case, and tribes have spent the decades that followed fighting to get what’s owed to them under a 1908 Supreme Court ruling and long-standing treaties.

The possibility of this outcome was clear to attorneys and officials even at the time, according to thousands of pages of court files, correspondence, agency memos and other contemporary records unearthed and cataloged by University of Virginia history professor Christian McMillen, who shared them with ProPublica and High Country News. While Arizona and California’s fight was covered in the press at the time, the documents, drawn from the National Archives, reveal telling details from the case, including startling similarities in the way states have rebuffed tribes’ attempts to access their water in the ensuing 70 years.

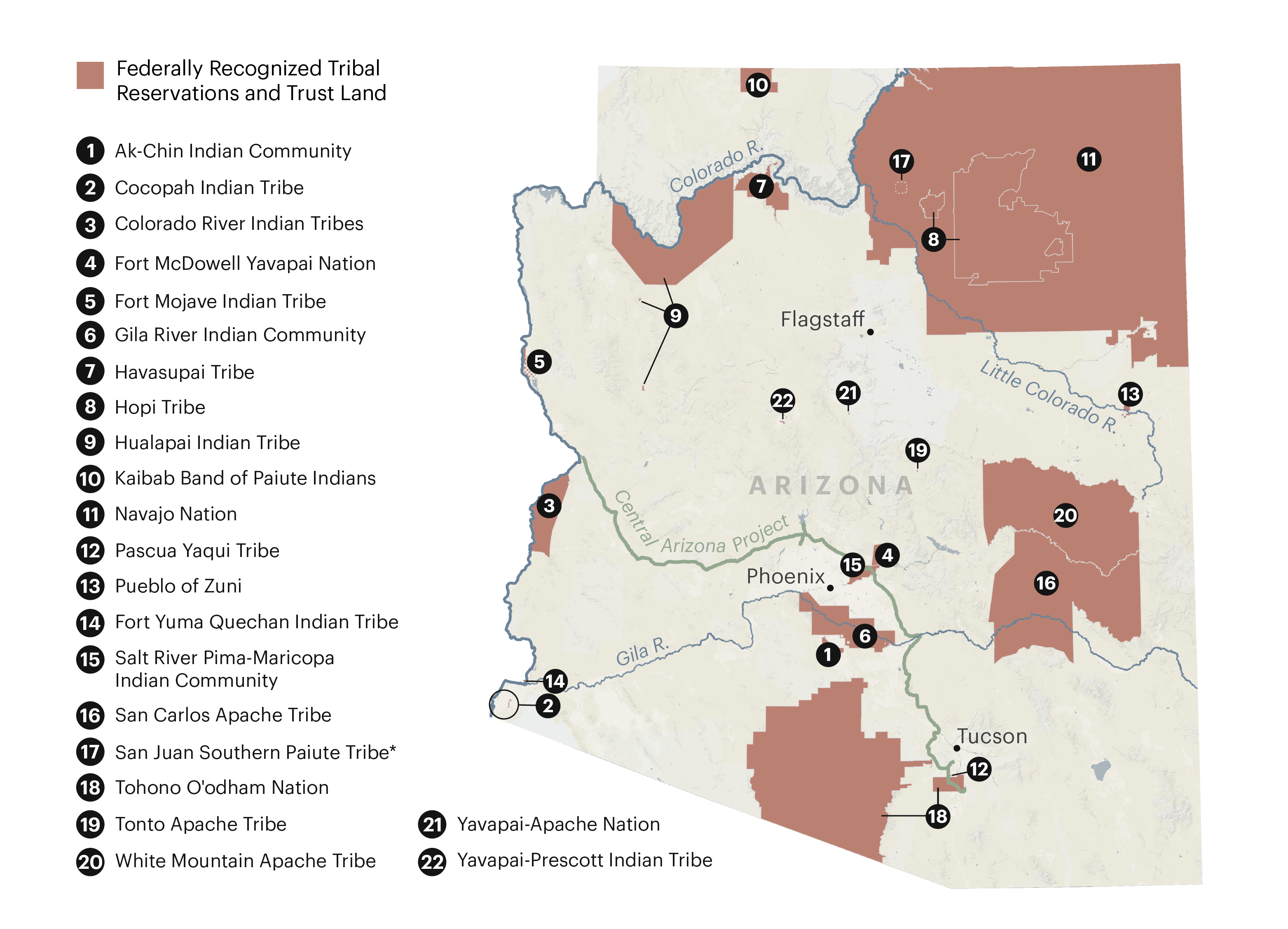

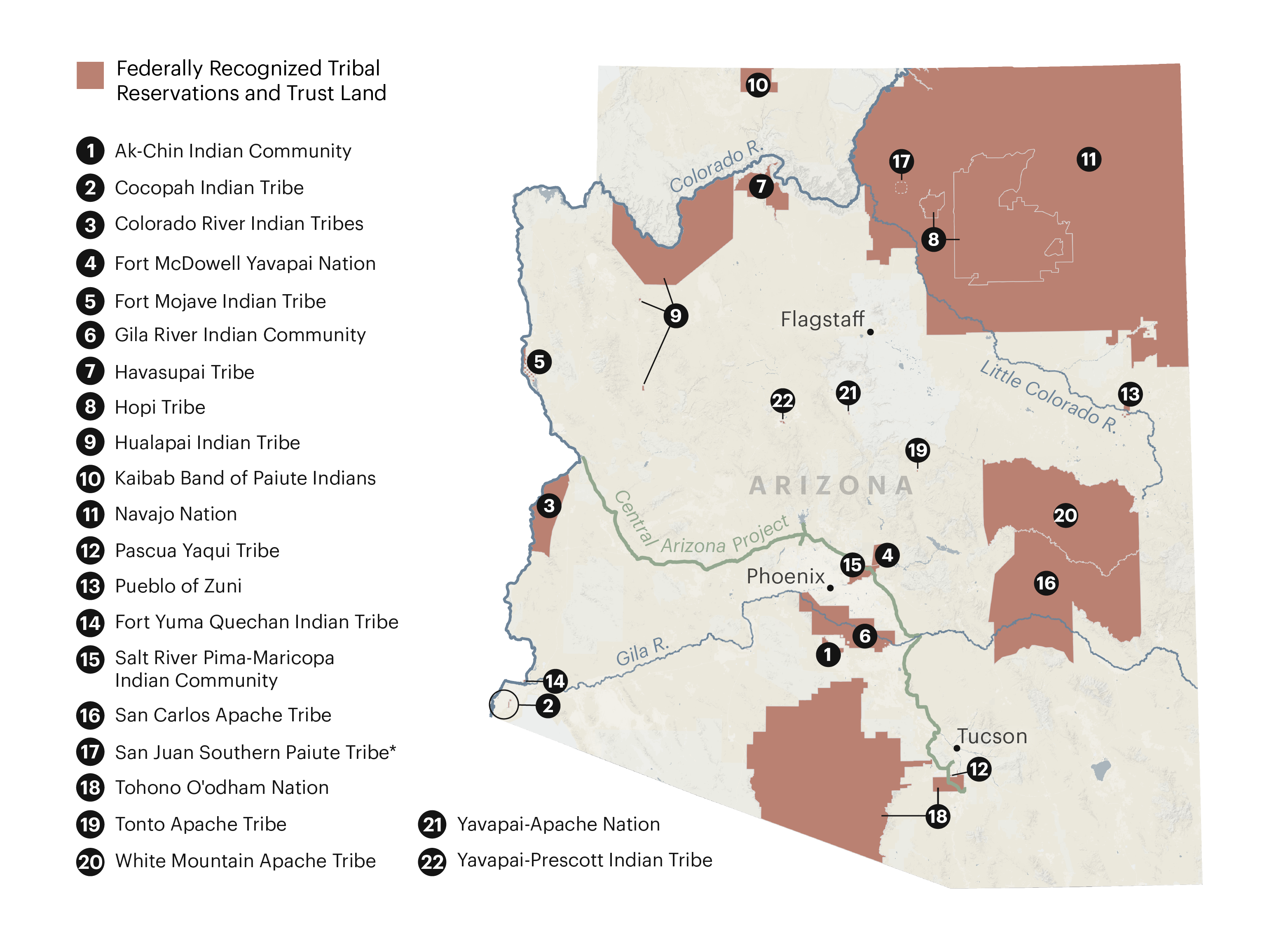

Many of the 30 federally recognized tribes in the Colorado River Basin still have been unable to access water to which they’re entitled. And Arizona for years has taken a uniquely aggressive stance against tribes’ attempts to use their water, a recent ProPublica and High Country News investigation found.

“It’s very much a repeat of the same problems we have today,” Andrew Curley, an assistant professor of geography at the University of Arizona and member of the Navajo Nation, said of the records. Tribes’ ambitions to access water are approached as “this fantastical apocalyptic scenario” that would hurt states’ economies, he said.

Arizona sued California in 1952, asking the Supreme Court to determine how much Colorado River water each state deserved. The records show that, even as the states fought each other in court, Arizona led a coalition of states in jointly lobbying the U.S. attorney general to cease arguing for tribes’ water claims. The attorney general, bowing to the pressure, removed the strongest language in the petition, even as Department of Justice attorneys warned of the consequences. “Politics smothered the rights of the Indians,” one of the attorneys later wrote.

The Supreme Court’s 1964 decree in the case quantified the water rights of the Lower Basin states — California, Arizona and Nevada — and five tribes whose lands are adjacent to the river. While the ruling defended tribes’ right to water, it did little to help them access it. By excluding all other basin tribes from the case, the court missed an opportunity to settle their rights once and for all.

The Navajo Nation — with a reservation spanning Arizona, New Mexico and Utah — was among those left out of the case. “Clearly, Native people up and down the Colorado River were overlooked. We need to get that fixed, and that is exactly what the Navajo Nation is trying to do,” said George Hardeen, a spokesperson for the Navajo Nation.

Today, millions more people rely on a river diminished by a hotter climate. Between 1950 and 2020, Arizona’s population alone grew from about 750,000 to more than 7 million, bringing booming cities and thirsty industries.

Meanwhile, the Navajo Nation is no closer to compelling the federal government to secure its water rights in Arizona. In June, the Supreme Court again ruled against the tribe, in a separate case, Arizona v. Navajo Nation. Justice Neil Gorsuch cited the earlier case in his dissent, arguing the conservative court majority ignored history when it declined to quantify the tribe’s water rights.

McMillen agreed. The federal government “rejected that opportunity” in the 1950s and ’60s to more forcefully assert tribes’ water claims, he said. As a result, “Native people have been trying for the better part of a century now to get answers to these questions and have been thwarted in one way or another that entire time.”

Three missing words

As Arizona prepared to take California to court in the early 1950s, the federal government faced a delicate choice. It represented a host of interests along the river that would be affected by the outcome: tribes, dams, and reservoirs and national parks. How should it balance their needs?

The Supreme Court had ruled in 1908 that tribes with reservations had an inherent right to water, but neither Congress nor the courts had defined it. The 1922 Colorado River Compact, which first allocated the river’s water, also didn’t settle tribal claims.

In the decades that followed the signing of the compact, the federal government constructed massive projects — including the Hoover, Parker and Imperial dams — to harness the river. Federal policy at the time was generally hostile to tribes, as Congress passed laws eroding the United States’ treaty-based obligations. Over a 15-year period, the country dissolved its relationships with more than 100 tribes, stripping them of land and diminishing their political power. “It was a very threatening time for tribes,” Curley said of what would be known as the Termination Era.

So it was a shock to states when, in November 1953, Attorney General Herbert Brownell Jr. and the Department of Justice moved to intervene in the states’ water fight and aggressively staked a claim on behalf of tribes. Tribal water rights were “prior and superior” to all other water users in the basin, even states, the federal government argued.

Western states were apoplectic.

Arizona Gov. John Howard Pyle quickly called a meeting with Brownell to complain, and Western politicians hurried to Washington, D.C. Under political pressure, the Department of Justice removed the document four days after filing it. When Pyle wrote to thank the attorney general, he requested that federal solicitors work with the state on an amended version. “To have left it as it was would have been calamitous,” Pyle said.

The federal government refiled its petition a month later. It no longer asserted that tribes’ water rights were “prior and superior.”

When details of the states’ meeting with the attorney general emerged in court three years later, Littell, the Navajo Nation’s attorney, berated the Department of Justice for its “equivocating, pussy-footing” defense of tribes’ water rights. “It is rather a shocking situation, and the Attorney General of the United States is responsible for it,” he said during court hearings.

Arizona’s legal representative balked at discussing the meeting in open court, calling it “improper.”

Experts told ProPublica and High Country News that it’s impossible to quantify the impact of the federal government’s failure to fully defend tribes’ water rights. Reservations might have flourished if they’d secured water access that remains elusive today. Or, perhaps basin tribes would have been worse off if they had been given only small amounts of water. Amid the overt racism of that era, the government didn’t consider tribes capable of extensive development.

Jay Weiner, an attorney who represents several tribes’ water claims in Arizona, said the important truth the documents reveal is the federal government’s willingness to bow to states instead of defending tribes. Pulling back from its argument that tribes’ rights are “prior and superior” was but one example.

“It’s not so much the three words,” Weiner said. “It’s really the vigor with which they would have chosen to litigate.”

Because states succeeded in spiking “prior and superior,” they also won an argument over how to account for tribes’ water use. Instead of counting it directly against the flow of the river, before dealing with other users’ needs, it now comes out of states’ allocations. As a result, tribes and states compete for the scarce resource in this adversarial system, most vehemently in Arizona, which must navigate the water claims of 22 federally recognized tribes.

In 1956, W.H. Flanery, the associate solicitor of Indian Affairs, wrote to an Interior Department official that Arizona and California “are the Indians’ enemies and they will be united in their efforts to defeat any superior or prior right which we may seek to establish on behalf of the Indians. They have spared and will continue to spare no expense in their efforts to defeat the claims of the Indians.”

Western states battle tribal water claims

As arguments in the case continued through the 1950s, an Arizona water agency moved to block a major farming project on the Colorado River Indian Tribes’ reservation until the case was resolved, the newly uncovered documents show. Decades later, the state similarly used unresolved water rights as a bargaining chip, asking tribes to agree not to pursue the main method of expanding their reservations in exchange for settling their water claims.

Highlighting the state’s prevailing sentiment toward tribes back then, a lawyer named J.A. Riggins Jr. addressed the river’s policymakers in 1956 at the Colorado River Water Users Association’s annual conference. He represented the Salt River Project — a nontribal public utility that manages water and electricity for much of Phoenix and nearby farming communities — and issued a warning in a speech titled, “The Indian threat to our water rights.”

“I urge that each of you evaluate your ‘Indian Problem’ (you all have at least one), and start NOW to protect your areas,” Riggins said, according to the text of his remarks that he mailed to the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Riggins, who on multiple occasions warned of “‘Indian raids’ on western non-Indian water rights,” later lobbied Congress on Arizona’s behalf to authorize a canal to transport Colorado River water to Phoenix and Tucson. He also litigated Salt River Project cases as co-counsel with Jon Kyl, who later served as a U.S. senator. (Kyl, who was an architect of Arizona’s tribal water rights strategy, told ProPublica and High Country News that he wasn’t aware of Riggins’ speech and that his work on tribal water rights was “based on my responsibility to represent all of the people of Arizona to the best of my ability, which, of course, frequently required balancing competing interests.”)

While Arizona led the opposition to tribes’ water claims, other states supported its stance.

“We thought the allegation of prior and superior rights for Indians was erroneous,” said Northcutt Ely, California’s lead lawyer in the proceedings, according to court transcripts. If the attorney general tried to argue that in court, “we were going to meet him head on,” Ely said.

When Arizona drafted a legal agreement to exclude tribes from the case, while promising to protect their undefined rights, other states and the Department of the Interior signed on. It was only rejected in response to pressure from tribes’ attorneys and the Department of Justice.

McMillen, the historian who compiled the documents reviewed by ProPublica and High Country News, said they show Department of Justice staff went the furthest to protect tribal water rights. The agency built novel legal theories, pushed for more funding to hire respected experts and did extensive research. Still, McMillen said, the department found itself “flying the plane and building it at the same time.”

Tribal leaders feared this would result in the federal government arguing a weak case on their behalf. The formation of the Indian Claims Commission — which heard complaints brought by tribes against the government, typically on land dispossession — also meant the federal government had a potential conflict of interest in representing tribes. Basin tribes coordinated a response and asked the court to appoint a special counsel to represent them, but the request was denied.

So too was the Navajo Nation’s later request that it be allowed to represent itself in the case.

Arizona v. Navajo Nation

More than 60 years after Littell made his plea to Kennedy, the Navajo Nation’s water rights in Arizona still haven’t been determined, as he predicted.

The decision to exclude the Navajo Nation from Arizona v. California influenced this summer’s Supreme Court ruling in Arizona v. Navajo Nation, in which the tribe asked the federal government to identify its water rights in Arizona. Despite the U.S. insisting it could adequately represent the Navajo Nation’s water claims in the earlier case, federal attorneys this year argued the U.S. has no enforceable responsibility to protect the tribe’s claims. It was a “complete 180 on the U.S.’ part,” said Michelle Brown-Yazzie, assistant attorney general for the Navajo Nation Department of Justice’s Water Rights Unit and an enrolled member of the tribe.

In both cases, the federal government chose to “abdicate or to otherwise downplay their trust responsibility,” said Joe M. Tenorio, a senior staff attorney at the Native American Rights Fund and a member of the Santo Domingo Pueblo. “The United States took steps to deny tribal intervention in Arizona v. California and doubled down their effort in Arizona vs. Navajo Nation.”

In June, a majority of Supreme Court justices accepted the federal government’s argument that Congress, not the courts, should resolve the Navajo Nation’s lingering water rights. In his dissenting opinion, Gorsuch wrote, “The government’s constant refrain is that the Navajo can have all they ask for; they just need to go somewhere else and do something else first.” At this point, he added, “the Navajo have tried it all.”

As a result, a third of homes on the Navajo Nation still don’t have access to clean water, which has led to costly water hauling and, according to the Navajo Nation, has increased tribal members’ risk of infection during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Eight tribal nations have yet to reach any agreement over how much water they’re owed in Arizona. The state’s new Democratic governor has pledged to address unresolved tribal water rights, and the Navajo Nation and state are restarting negotiations this month. But tribes and their representatives wonder if the state will bring a new approach.

“It’s not clear to me Arizona’s changed a whole lot since the 1950s,” Weiner, the lawyer, said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Western states opposed tribes’ access to the Colorado River 70 years ago. History is repeating itself. on Oct 28, 2023.