This story was co-published with Native News Online.

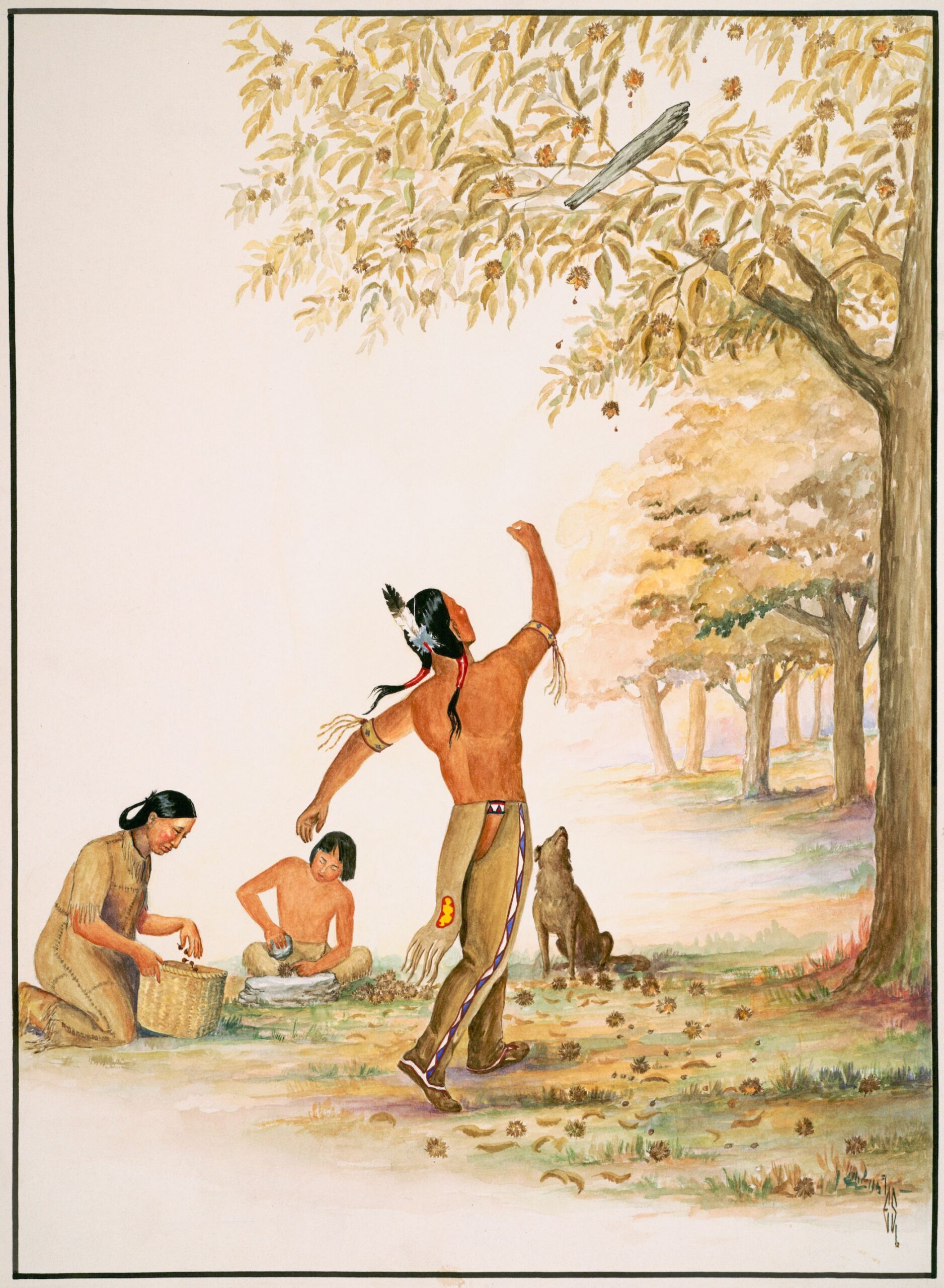

When Neil Patterson Jr. was about 7 or 8 years old, he saw a painting called “Gathering Chestnuts,” by Tonawanda Seneca artist Ernest Smith. Patterson didn’t realize that the painting showed a grove of American chestnuts, a tree that had been all but extinct since his great-grandparents’ time. Instead, what struck Patterson was the family in the foreground: As a man throws a wooden club to knock chestnuts from the branches above, a child shells the nuts and a woman gathers them in a basket. Even the dog seems engrossed in the process, watching with head cocked as the club sails through the air.

Patterson grew up on the Tuscarora Nation Reservation just south of Lake Ontario near Niagara Falls. The painting reminded him of his elders teaching him to harvest black walnuts and hickories.

“I think, for me, it wasn’t about the tree, it was about a way of life,” said Patterson, who today is in his 40s, with silver-flecked dark hair and kids of his own. He sounded wistful.

The American chestnut tree, or číhtkęr in Tuscarora, once grew across what is currently the eastern United States, from Mississippi to Georgia, and into southeastern Canada. The beloved and ecologically important species was harvested by Indigenous peoples for millennia and once numbered in the billions, providing food and habitat to countless birds, insects, and mammals of eastern forests, before being wiped out by rampant logging and a deadly fungal blight brought on by European colonization.

Now, a transgenic version of the American chestnut that can withstand the blight is on the cusp of being deregulated by the U.S. government. (Transgenic organisms contain DNA from other species.) When that happens, people will be able to grow the blight-resistant trees without restriction. For years, controversy has swirled around the ethics of using novel biotechnology for species conservation. But Patterson, who previously directed the Tuscarora Environment Program and today is the assistant director of the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment at the State University of New York’s College of Environmental Science and Forestry in Syracuse, has a different question: What good is bringing back a species without also restoring its traditional relationships with the Indigenous peoples who helped it flourish?

That deep history is not always clear from conservation narratives about the blight-resistant chestnut. For the past four decades, the driving force behind the chestnut’s restoration has been The American Chestnut Foundation, a nonprofit with more than 5,000 active members in 16 chapters. Before turning to genetic engineering, the foundation tried unsuccessfully to breed a hybrid chestnut that looked and grew like an American chestnut but had genes from species native to Asia that gave it blight resistance. “Our vision is a robust eastern forest restored to its splendor,” reads The American Chestnut Foundation’s homepage, against a background of glowing green chestnut leaflets. “Our mission is to return the iconic American chestnut to its native range.”

But the Foundation website’s history of the tree begins during colonial times, suggesting a romantic notion of a precolonial wilderness that ignores the intensive agroforestry that Indigenous peoples practiced. By engineering vanished species to survive harms brought on by colonization without addressing those harms, people avoid having to make hard decisions about how most of us live on the landscape today.

Bill Powell began working on chestnut genetics when he was a 28-year-old graduate student in Utah, which is actually outside the tree’s natural range. Now in his late 60s, with silvery hair, glasses, and an infectious curiosity about the relationship between tree and pathogen, he’s a leading chestnut restoration expert.

When I met Powell in 2022, he fretted that the chestnut restoration process was taking too long. “Unfortunately, I see retirement on the horizon,” he told me. “But not anytime soon, because I have to get this done.” At the time, Powell was a colleague of Patterson’s, working for the same university and directing the American Chestnut Research and Restoration Project. Since then, as the blight-resistant tree has wound its way through the deregulatory labyrinth of federal agencies including the Environmental Protection Agency, Food and Drug Administration, and Department of Agriculture, Powell has had to step down, recently sharing his diagnosis of terminal colon cancer publicly.

When we spoke, Powell stressed that after the blight-resistant chestnut is deregulated, no Indigenous nations will have to grow the transgenic trees on their lands if they choose not to. But he acknowledged that this does not reassure those who think of Indigenous land not in colonial terms, meaning within reservation boundaries, but instead in terms of treaty rights or cultural practices on historic tribal lands. Indigenous nations, including members of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy such as the Tuscarora Nation, have long argued that even when they ceded land to colonial governments, they did not cede their rights to access and care for plants and animals on those lands.

The nuts of the American chestnut are small, sweet, and nutritious. They were an important part of the varied diet that sustained Patterson’s ancestors for millennia; in return, people cared for groves of the trees across thousands of miles. When the United States pushed Indigenous peoples throughout the chestnut’s range off their lands, and the American chestnut became functionally extinct, an ancient reciprocal relationship vanished, too.

“We were instructed to pick those nuts,” Patterson said. “And when we don’t pick them, the plant goes away.”

With craggy bark and shaggy branches of feathery leaves, the American chestnut could reach 100 feet tall during its heyday. Its trunk could be 13 feet wide. The trees huddled along the Gulf Coast for some 8,000 years during the most recent ice age, sheltering in the relatively warm stretch from Florida to the Mississippi River, because mountain peaks even in the southernmost part of the Appalachians were too cold for chestnut trees to grow. Then, as the snow receded northward 20,000 ago, the trees slowly migrated from their coastal refuges. They worked their way up the Appalachian Mountains — helped by Indigenous peoples, whom they helped in turn.

The trees dropped an avalanche of chestnuts to the forest floor each year. According to historian Donald Edward Davis, people burned low fires that dried the nuts and killed off chestnut weevils. By suppressing other plants, fires helped the chestnut trees spread, and the nuts became staples of Indigenous diets — a reliable source of nutrition that people stored in earthen silos or pounded into flour for chestnut bread and other foods. The human-tended groves also fed animals such as elk, deer, bison, bears, passenger pigeons, panthers, wolves, and foxes. Chestnut logjams in streams created deep, clear pockets of water where fish could thrive. Several species of invertebrates relied on chestnut trees for habitat; after the trees died out, five species of moths went extinct.

European settlers forced Indigenous peoples along the chestnut’s range from much of their homelands, severing access to plants and animals they’d long interacted with. Meanwhile, settlers cut down chestnuts for many reasons — to clear space for towns and farms; to build fence posts, telegraph poles, and railroads; or just to gather the nuts more easily.

Nevertheless, the chestnut survived for centuries. Enslaved people gathered chestnuts to supplement meager meals and to sell. White Appalachian communities came to rely on chestnuts as free feed for their hogs and other livestock, and as a cash crop.

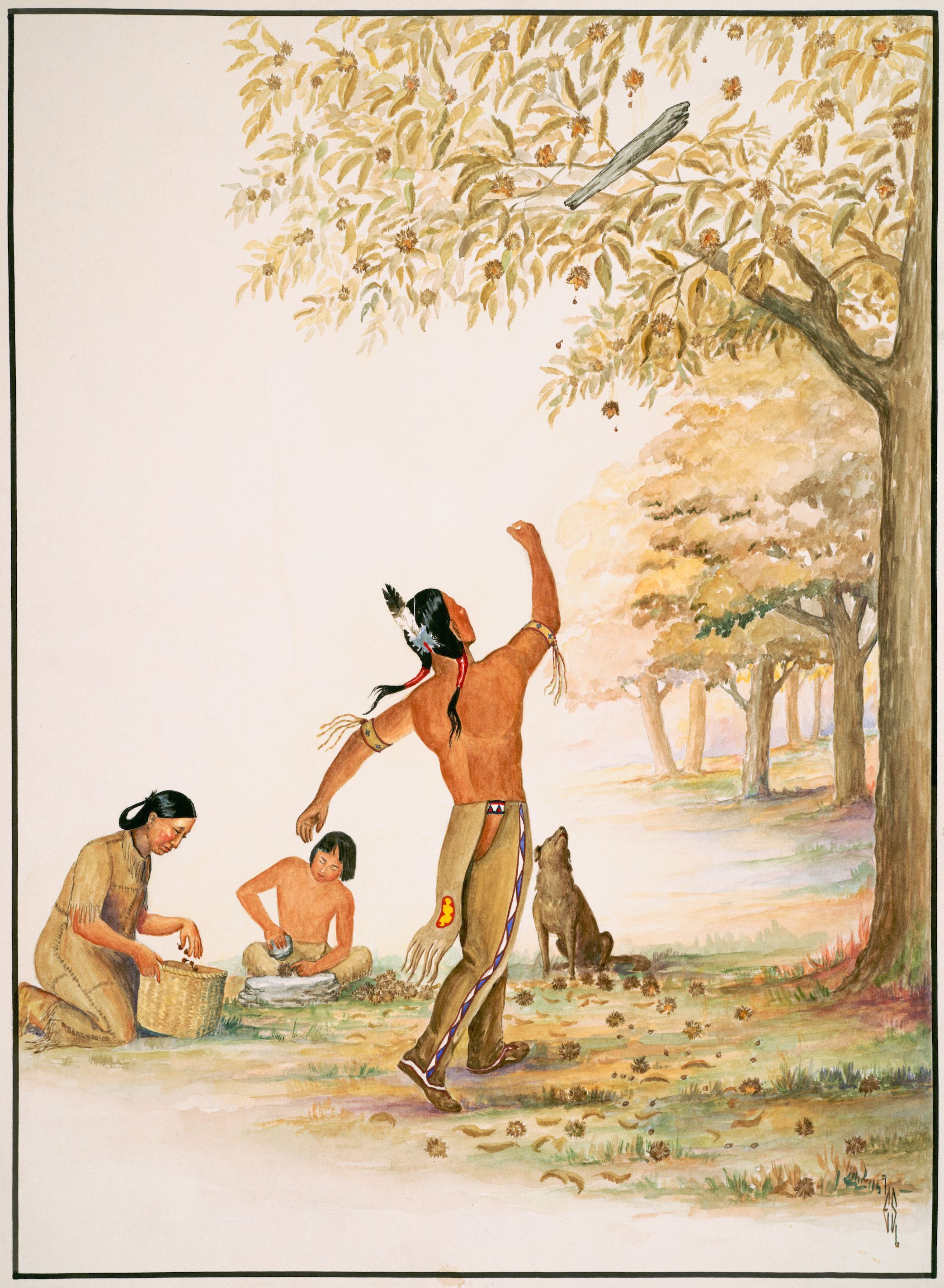

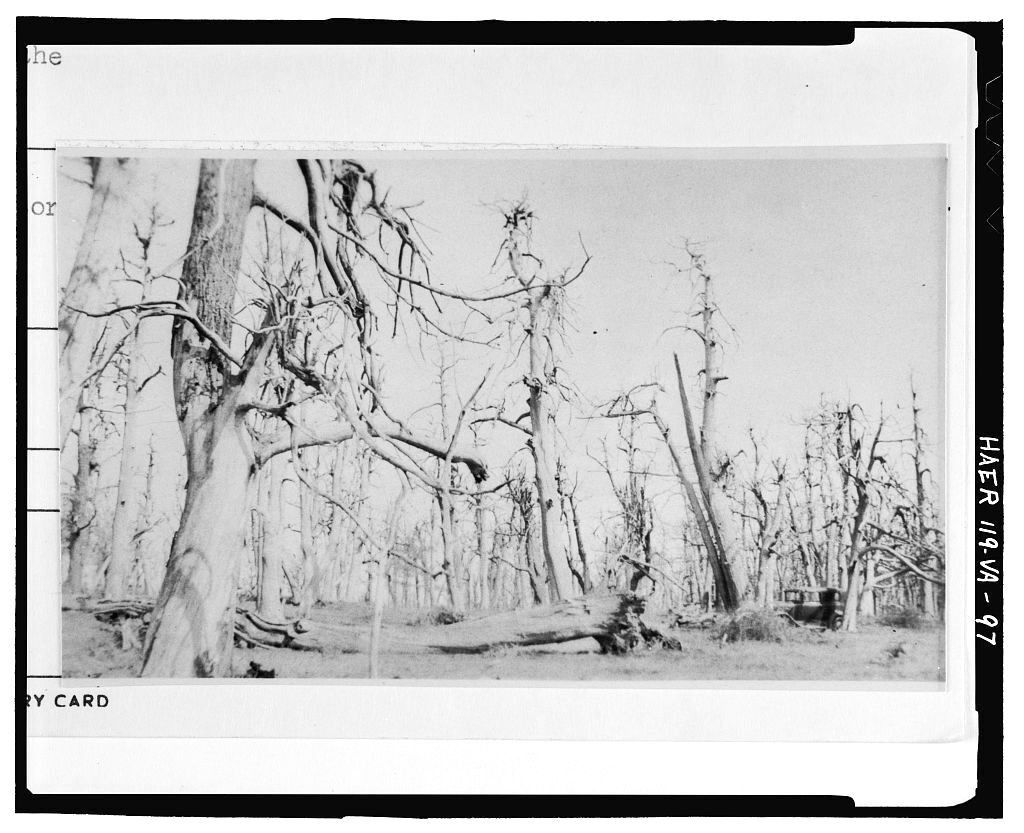

Then, in the late 1800s, horticulturalists imported trees carrying the fungal blight Cryphonectria parasitica to the United States. The blight spread by wind and splashing rain; it also hitched rides on insects and birds. Once it landed on the bark of a new tree, it dug in through weak spots — old burn injuries, insect wounds, or scars left from woodcutting — and dissolved the tree’s living tissue with oxalic acid, creating angry orange streaks and open cankers on trunks. The trees would die back to their roots, resprout, and die back again, like botanical zombies. The blight killed at an astonishing pace. All told, a tree whose ancestors evolved millions of years ago died out in less than 50 years.

In turn, the chestnut lost the people whose practices helped it thrive. Patterson told me that some Indigenous nations even lost their word for the chestnut tree, because chestnuts disappeared at the same time that the U.S. government took Indigenous children, including at least one of Patterson’s own relatives, and placed them in boarding schools. In part, this was another strategy for coercing tribes to give up territory. Many children didn’t survive the schools, which were often run by Christian organizations. Those who did were forced to give up their languages, religious beliefs, and traditions. But chestnuts still inhabit Indigenous creation stories and religious calendars, and Patterson believes that a reciprocal relationship can be reestablished between Indigenous nations and the tree. He’s just not convinced that releasing the transgenic chestnut will restore those connections.

The Tuscarora Nation, of which Patterson is an enrolled citizen, is one of six Indigenous nations that today comprise the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, also known as the Iroquois Confederacy. The Haudenosaunee creation story, Patterson said, is “a cycle of loss, grieving, and recovery all the time, just like ecological succession.” By creating a genetically engineered chestnut, Patterson argues, scientists are avoiding the part of the cycle where people grieve and learn from their mistakes.

On the timescale of Haudenosaunee history, the losses still feel new. “It’s been 100 years — but that’s not long,” Patterson observed. Then he reconsidered. “That’s long for research scientists, or a plant technology innovator. It’s too long.”

To Patterson, what’s not being restored — treaty rights to access and care for plants and animals on the landscape — is telling.

“If you want to restore this, like, ‘primordial’ forest, don’t you also want to restore our relationship with that forest?” he asked. “Like — what’s your relationship to a transgenic chestnut?”

Library of Congress

By the time Patterson first saw Ernest Smith’s artwork in the early 1980s, the Tuscarora Nation was going through a cultural renaissance. Patterson’s mother made her children speak Tuscarora at home to keep the language alive. His relatives participated in political acts such as the occupation of Wounded Knee by Indigenous people from across the U.S., in part to demand that the federal government uphold treaty obligations to the Lakota people. Murals on the walls of Patterson’s state-run elementary school showed Tuscarora people hunting, fishing, trapping, and gathering, even as non-Indigenous people contested those traditional activities outside of reservation lands, from the local to the national level.

Over time, Patterson was taught that the Haudenosaunee Confederacy never ceded its “reserved rights,” or rights that are not explicitly mentioned in treaties or court cases. Today, the Confederacy maintains that it still holds rights to care for and access the species growing on its ancestral homelands and in ancestral waterways — even in territory ceded to settlers. But both the state of New York and the federal government have chipped away at those reserved rights through court cases, and often won. In this legal context, harvesting chestnuts, like the family in Smith’s painting, is not only a cultural practice; it’s an exercise of tribal sovereignty.

Patterson works to rebuild tribal access to many plants and animals that are culturally important for Haudenosaunee peoples. Because those plants and animals often live outside of reservation lands, his work can be difficult. New York State maintains that, except on reservation lands, Indigenous peoples have the same rights as non-Indigenous peoples, and have to follow the same regulations regarding when, where, and how much they hunt, fish, or gather, such as hunting seasons or fishing licenses — regulations the Tuscarora have been fighting in court for decades. So to Patterson, the question of whether to grow transgenic trees isn’t really the most urgent one. He’s more concerned about upholding a way of life that restores traditional ecological relationships.

“Aside from the whole issue of being transgenic, this is just about access and care of place,” he told me. In New York’s state lands, he added, there are almost no provisions for gathering medicines, collecting food, or growing food in traditional territories. Yet that reciprocity helped chestnuts spread and thrive across thousands of miles and thousands of years.

The Haudenosaunee Confederacy began making treaties with white settlers more than 400 years ago. The two-row wampum belt, made of rows of white beads run through with two rows of purple beads, documents a 1613 agreement between the Haudenosaunee and Dutch settlers to live in parallel, not interfering with each other’s ways of life. In 1794, during George Washington’s presidency, the Haudenosaunee and the United States signed the Treaty of Canandaigua, affirming the Confederacy’s sovereignty on its territory. In the Nonintercourse Act, a series of statutes passed in the late 1700s and early 1800s, Congress also barred states from purchasing lands from Indigenous nations without federal approval. When states’ land purchases are approved, Indigenous nations don’t lose any other rights on those lands, such as hunting, fishing, or gathering, unless the treaty specifically cedes those rights, explained Monte Mills, who directs the Native American Law Center at the University of Washington.

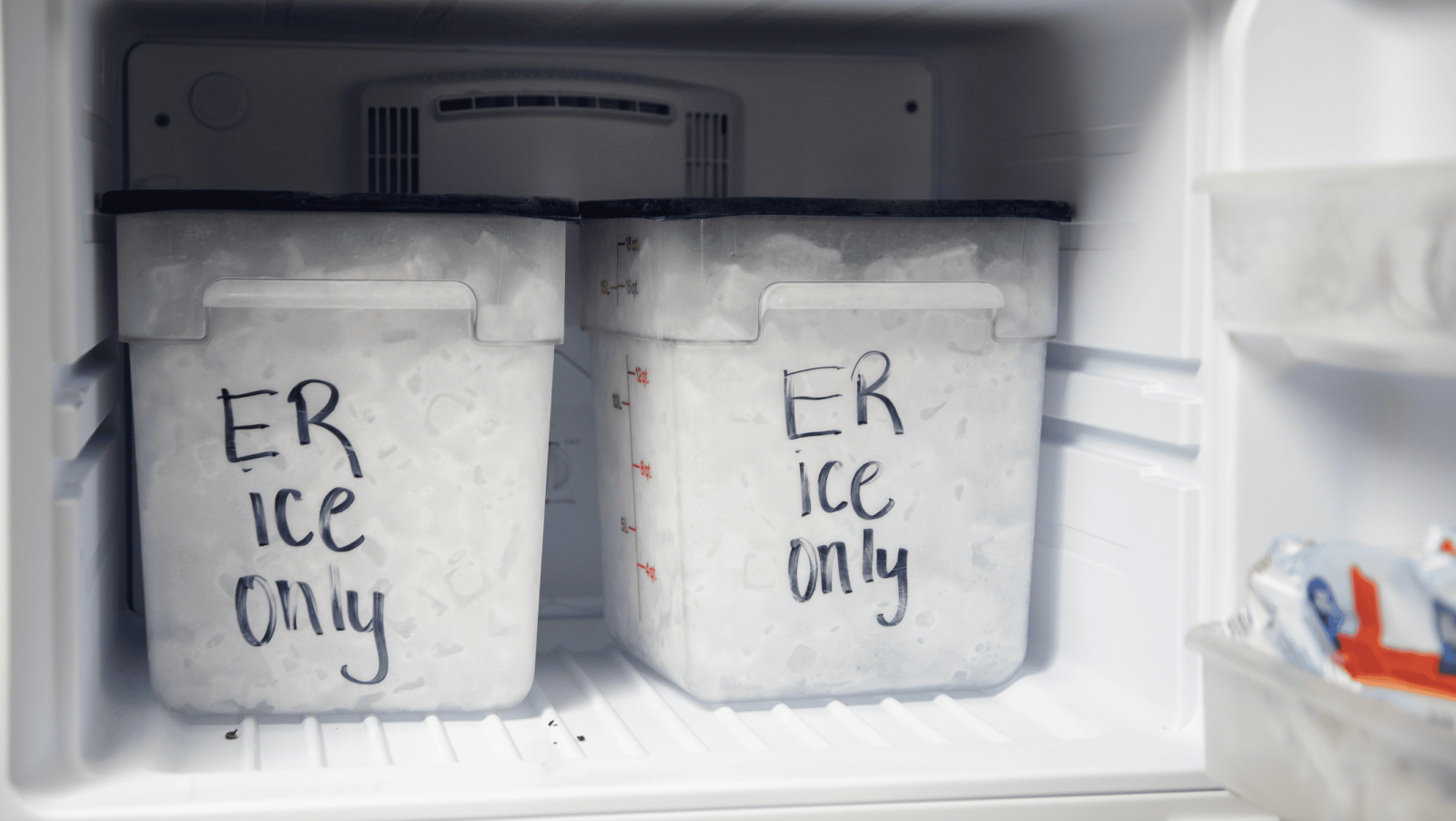

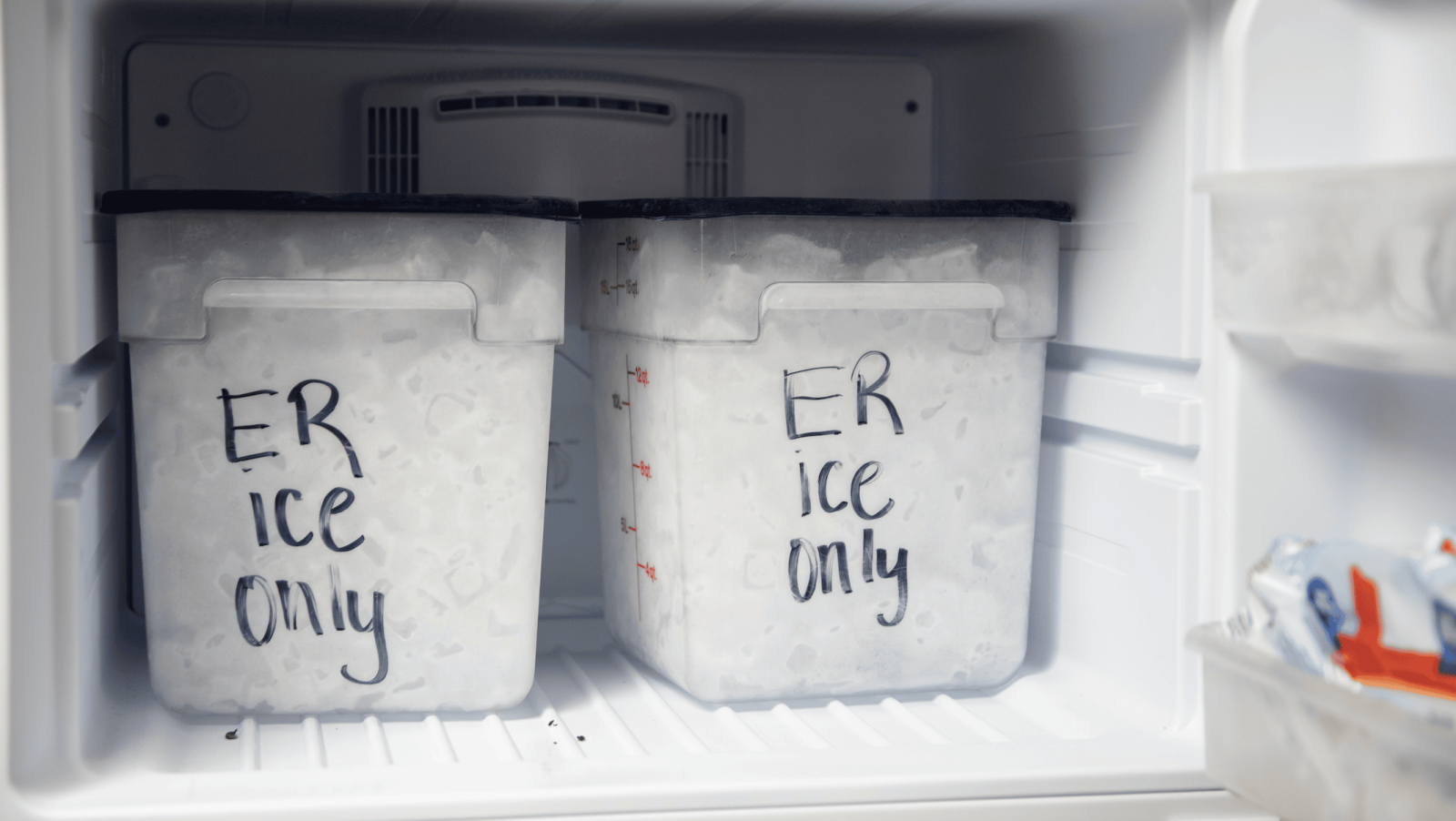

Nonetheless, states including New York still try to assert control over tribes or tribal resources, and in many cases, succeed. In one 2005 case, Patterson himself was the defendant, charged by the state of New York for ice fishing without properly labeling his gear. Patterson brought a copy of the Treaty of Canandiagua to court, explaining to the judge that as a member of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, he had the right to fish in the state park, formerly Seneca territory, without regulation by the state of New York. Patterson lost that case.

The Supreme Court of the United States has also limited Haudenosaunee reserved rights, though from a different angle. In City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York, decided just a few months before Patterson’s case, the Supreme Court ruled that although the Oneida Nation, which is part of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, never gave up certain rights on its ancestral land, it had essentially waited too long to exercise them.

This particular case centered around whether tribes had to pay local and state taxes on ancestral land that they bought back on the real estate market. In the majority opinion, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg wrote that both Indian law and the need to treat people equally “preclude the Tribe from rekindling embers of sovereignty that long ago grew cold.” According to Mills, the Supreme Court essentially said that Oneida had let too much time pass to assert its sovereign rights, and therefore had lost them.

“It’s one of the worst decisions from foundational Indian law court,” Mills said. Although the case was about property taxes, Mills said that it could be a precedent for preventing Indigenous nations from exercising reserved rights. “The state would probably point to Sherrill and say, ‘No, you can’t have those rights, because you haven’t asserted them for so long,’” he added.

But Mills also pointed out that sometimes, tribes and states have been able to work together to come up with mutually beneficial ways for tribes to exercise their reserved rights. If states are interested in recognizing tribal sovereignty, he said, there are models out there for how to do it.

For its part, the state of New York has been working recently to improve its relations with Indigenous nations. In 2022, the state and the federal government agreed to return more than 1,000 acres to the Onondaga Nation. That same year, Governor Kathy Hochul’s administration created an Office of Indian Nation Affairs in the Department of Environmental Conservation, the same department that 20 years previously ticketed Patterson and fought him in court over reserved fishing rights. Peter Reuben, who is enrolled in the Tonawanda Seneca Nation, is currently serving as the first director of the new office.

To Reuben, the creation of his position by the department “really shows that they are serious about us,” he said. Reuben is working to create a productive and respectful consultation process between the region’s Indigenous nations and the state of New York on environmental issues, and to hash out agreements over hunting, fishing, and treaty rights.

“If it’s in the state’s interest — which it seems like it would be — to have more support and additional resources for natural resource management, then why not work with tribal folks to support a program where they’re able to continue to do what they said they’ve been doing all along?” Mills said. “It’s probably going to lead to a better end result anyway.”

For now, while transgenic American chestnut trees are still highly regulated, one of the best places to see one is at the Lafayette Road Experimental Field Station on the southern outskirts of Syracuse. Powell met me there on a sunny July morning two summers ago.

On fields that glowed bean-pod green in the upstate humidity, thousands of chestnut trees grew in varying stages of reproduction, healing, and death. White paper bags festooned the taller trees, their flowers covered to manage fertilization.

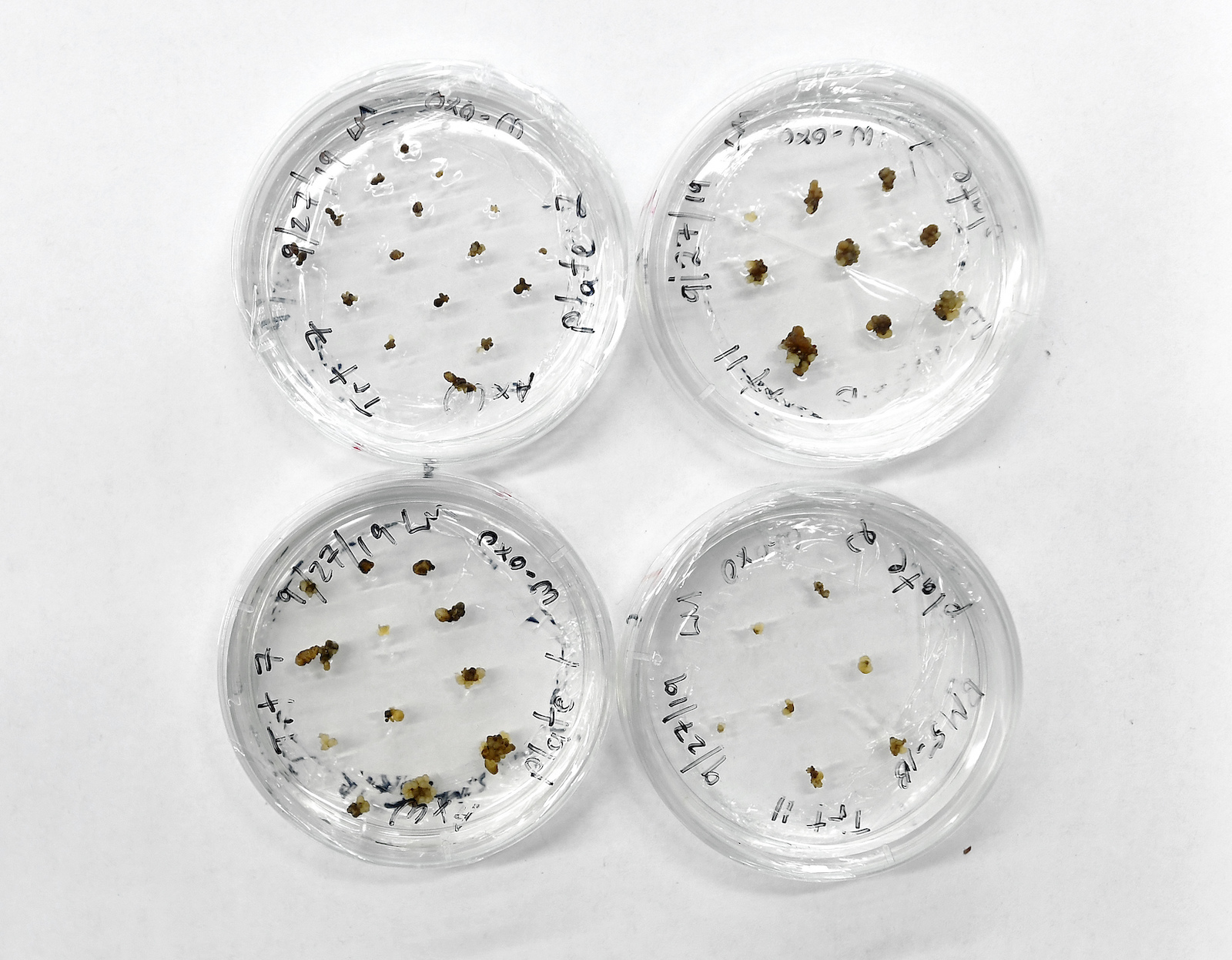

The transgenic chestnuts contain wheat DNA that lets the tree create an enzyme that fights off Cryphonectria parasitica, the fungal blight. The blight cankers on these trees don’t grow big enough to girdle them.

Rows of strappy transgenic saplings, some as tall as Powell, waited in holding plots fenced to keep out hungry deer. “We’re planting them on very close spacing, and we can only hold them for about three years, and then they get root-bound,” Powell said. As the permitting process drags on, time is running out to replant these young trees.

I asked Powell why he thought restoring the chestnut was important. Chestnuts produced a stable crop of nuts for wildlife, because they flowered late enough in the year that they escaped flower-killing frosts, he said. “It was just an important part of our ecosystem, and for our heritage, too,” he added. “The railroads that were made in the East used ties that were made out of chestnuts because they were rot resistant. And people used to say, chestnuts used to follow you from cradle to grave, because the wood was used in everything from cradles to coffins.”

Although he’s retired, Powell is working to create a research center that would develop transgenic versions of other native species going extinct from blights, insects, and other introduced pests. He imagined growing transgenic versions of everything from elms, killed off by Dutch elm disease and the elm yellows pathogen, to ash trees, which are currently being devoured by iridescent green beetles called emerald ash borers.

People who hope to use technology to resurrect extinct species, whether the American chestnut or even the woolly mammoth, are sometimes considered ecomodernists. According to Jason Delborne, who studies biotechnology and environmental policy at North Carolina State University (where I previously worked, in the English department), “There are people who are environmentalists at their core, but sick of losing, and interested in the promise of technology to solve the ecological and environmental problems we are facing.” Part of that interest, he said, comes from a sense of responsibility to “fix what you broke.”

Indeed, Jamie Van Clief, the southern regional science coordinator for The American Chestnut Foundation, explained to me that she got interested in working for the organization because her field, environmental science, was depressing.

“There’s a lot of disaster, there’s a lot of dismay, and to have this foundation with such a positive and impactful mission just attracted me immensely,” she said. “To be able to work towards something when it kind of feels hopeless sometimes — and to be part of restoration on the scale that we’re doing — is incredible.”

As Powell and I gazed at a diseased, non-engineered chestnut sapling, its yellowing leaves hanging limp in the sun, I reflected that eastern forests weren’t exactly flush with any other giant trees. Almost all old growth has fallen to human endeavors. Conservation efforts also have to take into consideration climate change, which may shift suitable chestnut habitat north into Canada — and shift plant diseases’ habitats as well. Root rot, or Phytophthora cinnamomi, is another introduced pathogen. It only infects chestnuts in the South right now, because root rot dies during winter freezes. The American Chestnut Foundation estimates root rot will spread to New England in the next 50 years as the region warms. Plus, there are few places available for a new chestnut forest to grow, except perhaps forest remediation sites such as old Appalachian coal mines. The fact is, releasing blight-resistant chestnuts into the wild won’t guarantee them a landscape where they can survive.

Because biotechnology alone can’t restore the American chestnut to the numbers that its supporters are envisioning, Powell anticipates relying on citizen scientists. After deregulation, he imagines The American Chestnut Foundation sending transgenic pollen to interested people, who could pollinate the flowers of wild mother trees growing nearby. They could plant the nuts the trees grow or pass them on to other chestnut fans.

The health and ecological risks of introducing the transgenic chestnut into the wild are likely to be low, according to Delborne; its signature wheat gene is commonly found in many major food crops. But at heart, Delborne argues, the debate isn’t just about chestnuts. “It’s also about a category of technology that could find its way into the world,” he said.

Even if the chestnut recovery doesn’t work out, the approval of the engineered chestnut for unregulated growth could open the door to a new era of biotechnology in U.S. forestry — such as a pest-resistant poplar tree, which kills forest insects by expressing genes from the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis, and already grows commercially in other countries.

The debate about blight-resistant chestnuts isn’t really about trees or even genetic engineering; it’s about who gets to make decisions on the land. Conservation is framed in European cultures as an objective goal, but it’s a worldview that other people may not share, explained Katie Barnhill-Dilling, a North Carolina State University social scientist who researches environmental decision-making. “Some of the people I’ve talked to from the Haudenosaunee Environmental Task Force would contest that humans are here to accept the gifts as they are now,” she said.

Some Indigenous nations in the chestnut’s historic range, such as the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, or EBCI, are considering growing genetically engineered chestnuts on their reservation lands after the trees are deregulated. To EBCI Secretary of Agriculture and Natural Resources Joey Owle, restoring the American chestnut is another way for the tribe to exercise its sovereign rights, more than a century after the tree’s disappearance.

“It’s one project of many projects that we work on to enhance our sovereignty as a tribe, to work to establish a culturally significant resource that provided a bountiful harvest for our ancestors and wildlife,” he said. “It’s just cool to be part of it.” Based on feedback from EBCI committee members, Owle said that planting transgenic trees, while an option, is the “last option that we would like to pursue” to restore the species. For now, the EBCI is scouting out wild chestnuts that survived the blight, and planting hybrid trees on its land in partnership with The American Chestnut Foundation.

On a crisp fall day a couple of years ago, Patterson and Powell arranged for around 15 people to gather chestnuts in upstate New York. The grove grew on a hilly slope on state land that used to be an agricultural field. “It was just a beautiful little spot,” Patterson recalled. The 12 or so American chestnuts were young; Patterson estimated they were perhaps 20 years old and no more than 25 feet tall.

The group, a mix of Haudenosaunee Confederacy members and non-Indigenous scientists, toted assorted equipment to gather the prickly nuts: ladders, homemade pickers, plastic buckets, sturdy leather shoes, and gloves. But first, they stood in a circle in the grove and discussed the future of the American chestnuts. According to Patterson, things quickly became adversarial.

Powell and Patterson had long been collegial: Patterson first tasted an American chestnut after he microwaved some that Powell handed him in the campus building where they both had offices. Meanwhile, Powell’s students learned from Patterson about the parallel expulsion of Indigenous peoples from their lands and the disappearance of chestnut trees.

Powell has constantly reached out to tribes for input and to understand their perspectives, Patterson said. And unlike other biotechnology researchers, Powell has focused on technology for environmental restoration, not for personal profit. “I admire the idea that this is about technology for restoration — whatever that is,” Patterson added.

But their relationships with plants remain fundamentally different. For example, Powell has talked about keeping the price of the transgenic chestnuts low, just to raise enough money to cover the costs of getting them out to people. In contrast, when I asked Patterson why he never bought or sold seeds from traditional food plants for his home garden, he sounded incredulous. “That’s like selling people,” he said. “That’s life. … Why would you sell somebody?”

That fall day, Patterson began worrying that if the restoration succeeds and transgenic chestnuts grow across the land, releasing pollen into the wind, people won’t be able to tell transgenic trees apart from non-transgenic trees. Scientists in the group assured everyone that in the future, people would be able to tell the trees apart through genetic testing.

“It was this privileged standpoint, which is, ‘Well, technology will figure it out for us.’ But it’s not as if I’m going to hand that technology to my son or nephews or my grandsons before they go off to gather,” Patterson said. “It just seemed like it was so simple to them.” He wondered why the non-Indigenous scientists and conservationists had been able to plant this grove on state land in the first place, when his nation was largely prevented from accessing or caring for plants there.

The group got tense. “The conversation turned to fear, and to moral opposition,” Patterson recalled. Patterson realized this standoff wasn’t the right frame of mind for the trip. “Well,” he exclaimed, “let’s go pick some nuts!”

As he collected chestnuts, Patterson couldn’t help but think of Ernest Smith’s painting. “It was a fulfillment of that scene,” he told me. Patterson reflected on his ancestors, wondering how they’d gathered the prickly nuts without his contemporary tools. He felt that by collecting chestnuts, he was doing what he was supposed to do. He hoped that in the future, he’d be able to find more wild chestnuts and organize more gathering trips, taking care to bring Haudenosaunee kids along. But he could see that the masting trees were struggling with the blight and weren’t going to survive much longer. Some of the young trees were already more than half dead, leaves brown and wilted.

He and his wife, who also attended the trip, were struck by a realization: If the federal government deregulated the blight-resistant trees, letting their pollen float freely through the air, this trip might be one of the last times they could gather wild American chestnuts with certainty.

*Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that Patterson’s relatives participated in the occupation of Alcatraz Island. Due to editing errors, the earlier version also incorrectly listed the Indigenous nations considering growing genetically engineered chestnuts and misidentified an 1885 print of a European chestnut.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline The American chestnut tree is coming back. Who is it for? on Sep 13, 2023.