Business travel is responsible for a large part of a company’s carbon emissions, negatively impacting…

The post Sustainable Business Travel: Navigating The Road To Greener Journeys appeared first on Earth911.

Business travel is responsible for a large part of a company’s carbon emissions, negatively impacting…

The post Sustainable Business Travel: Navigating The Road To Greener Journeys appeared first on Earth911.

This story was originally published by Honolulu Civil Beat and is republished with permission.

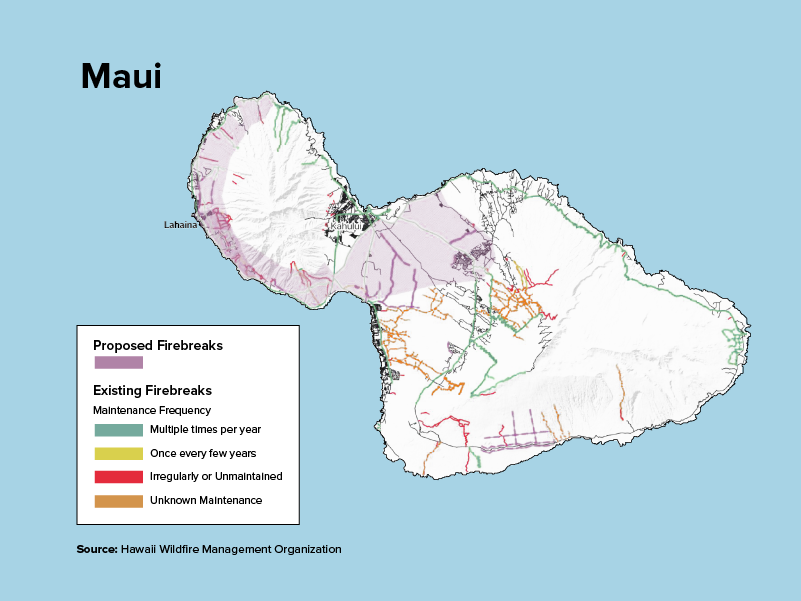

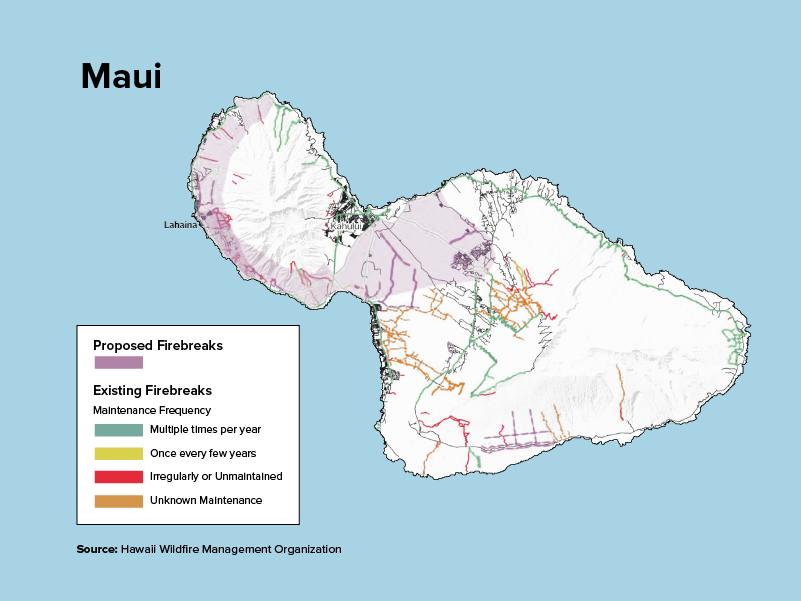

Hawaii maintains a network of firebreaks to keep wildfire from spreading, but that system includes hundreds of miles of gaps that need to be filled to protect communities around the state.

Public and private land managers dealing with the danger face bureaucratic barriers and a lack of money and collaboration.

Managing land to reduce fire danger took on increased urgency after the Aug. 8 wildfires on Maui, including the conflagration that leveled Lahaina and killed at least 115 people.

Both firebreaks and fuelbreaks are used to slow or halt the spread of wildfire. Firebreaks are generally wide belts of bare soil, but roads and rivers can serve the same purpose. Fuelbreaks are actively managed strips of land with minimal vegetation, intended to weaken the intensity and spread of fire.

Hawaii has roughly 4,300 miles of breaks, but needs approximately 350 miles more — accounting for some 400,000 acres, according to 2019 data collected by the Hawaii Wildfire Management Organization.

It’s doubtful that firebreaks around Lahaina on Aug. 8 would have stemmed the spread of the West Maui fire, given the high winds, HWMO co-executive director Elizabeth Pickett said. But the tracts play an integral role in helping firefighters access hard-to-reach areas to dissipate fires’ intensity.

As far back as 2018, fire officials and land managers identified a need for an additional 350 miles of breaks during meetings with representatives of 128 private and public groups and HWMO.

But because those breaks cross federal, state, county, and private lands, there must be collective buy-in and coordination to make it work, as well as money to pay for it all, Pickett said.

“Fire doesn’t recognize fence lines and ownerships and jurisdiction. So we need our fuels management to make sense at the land level,” Pickett said.

The 2018 meetings resulted in an assessment of the state’s needs that has informed much of its work on vegetation management until now.

But the effort has not received enough attention or money, officials say.

Building a firebreak on public land is expensive. The Department of Land and Natural Resources says it can’t afford to do it short of an emergency.

DLNR, which manages 26 percent of the state’s land, maintains just over 320 miles of breaks statewide but only cuts them during active wildfires. The department says the regulatory costs of protecting environmental, cultural, and historic resources make it unfeasible except during emergencies.

Those regulations are waived during active fires, when trained “dozer scouts” from DLNR’s Division of Forestry and Wildlife guide bulldozers to cut ribbons in the landscape to stop fire without destroying important resources.

The result is an “ad hoc network” of firebreaks and fuelbreaks, according to DOFAW forester Michael Walker.

To link it all together across boundaries will take time, staff and funding beyond DOFAW’s current capabilities, Walker says.

A bill that was killed this year would have set aside $3 million over two years for DOFAW to connect Hawaii’s breaks. Even that would have fallen far short, Walker says.

“And it’s not just us — forestry and wildlife — that need fuel reduction funds. It’s ranchers, farmers,” Walker said in a July interview before the Lahaina fire.

Farmers and ranchers are key players in preventing wildfire because they actively manage the landscape, either through grazing or crops. Land no longer used for these purposes has contributed to the spread of wildfire in recent decades.

Unused land has fostered the spread of invasive grasses, many thriving under drought conditions.

Much of this land now borders development.

“The bulk of the housing in Hawaii these days is built on top of old plantation land,” Walker said. “So they’ll develop a piece of it, but then the rest of it is still surrounded by fallow ag land.”

A week ago, a three-acre wildfire threatened three homes in Oahu’s Makakilo, a community that has consistently raised concerns over its single evacuation route. It came up again recently, in the aftermath of the Aug. 8 Maui fires.

On top of evacuation concerns, the Honolulu Fire Department said in a press release that there are too few firebreaks in the unmanaged land bordering the community.

Because wildfire does not respect property lines, it has been a focus for HWMO, which has been working on bolstering communication, funding, and coordination across the state.

That was the goal of HWMO’s 2018 meetings: to test and establish an “all hands, all lands” approach in Hawaii, according to co-executive director Pickett.

HWMO has tested community-based, cross-boundary fire mitigation projects on five of Hawaii’s major islands, allocating $22,000 to each project. They ranged from grazing sheep in Waianae to building a break in Kawaihae on Big Island.

But Pickett recognizes that her relatively small organization has only been able to focus on the community level.

“We want to think about what makes sense across boundaries,” Pickett said.

Not every landowner has been willing to take part. HWMO has focused on working with the willing.

But more needs to be done, including improved fire codes, legislation, and enforcement.

“Where’s the gap? Accountability,” Pickett said.

In light of the Aug. 8 fires, county and state lawmakers appear resolved to stem the risk of wildfire in Hawaii.

Last month, Honolulu Mayor Rick Blangiardi ordered a review of Oahu’s fire risk, including firefighting assets and capacity, unaddressed needs and system vulnerabilities.

Last week, the Hawaii House of Representatives established working groups to focus on several wildfire topics to inform bills in the next legislative session.

One of those groups will be focused on wildfire prevention.

One of its 16 members, Rep. David Tarnas, believes the state should coordinate the establishment of a robust network of breaks and creating incentives for vegetation management, because it all costs money.

The government entity mandated to do the work — DOFAW — has been underfunded for years, Tarnas said.

“We can’t just leave it to a nonprofit,” Tarnas said. “You know, we have to step up as a state and fully fund our natural resources and fire protection program.”

Civil Beat’s coverage of Maui County is supported in part by a grant from the Nuestro Futuro Foundation.

Civil Beat’s coverage of climate change is supported by the Environmental Funders Group of the Hawaii Community Foundation, Marisla Fund of the Hawaii Community Foundation and the Frost Family Foundation.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Hawaii needs to build hundreds more miles of firebreaks to protect against wildfire on Sep 17, 2023.

This story was originally published by The 19th and is republished with permission.

Pregnant people exposed to extreme heat are at higher risk of developing life-threatening complications during labor and delivery, according to new research published in the Journal of the American Medical Association last week. The research adds to a growing body of evidence showing the impact extreme heat has on a pregnancy, while also making a distinction between long-term exposure and events like heat waves.

“I think this [distinction] is really important,” said Ashley Ward, director of the Heat Policy Innovation Hub at Duke University who was not involved in the study. “Most of the research around pregnant women has centered on acute events like a heat wave … but honestly, what we are all experiencing this summer is an excellent example of really what I would consider chronic heat exposure.”

The researchers used data provided by Kaiser Permanente Southern California, a health care network, to identify over 400,000 pregnancies in the region that took place between 2007 and 2018. They then looked at temperature data from that same time period and used the daily maximum temperature to figure out how many days of heat — characterized as moderate, high or extreme — pregnant people were exposed to throughout their pregnancy, breaking it down by trimester.

The study found significant associations between both short- and long-term exposure (usually defined as 30 days or more) of environmental heat during a pregnancy and severe maternal morbidity. Severe maternal morbidity is a term used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to define 21 unexpected outcomes during labor or delivery that are considered near misses for maternal mortality. This could include cardiac arrest, eclampsia, heart failure, sepsis, and ventilation. (The primary findings excluded whether a blood transfusion occurred during delivery, usually an indicator of severe maternal morbidity, because the data wasn’t detailed enough.)

Researchers found that a high exposure to extreme heat through the duration of the pregnancy or in the third trimester was associated with a 27 percent increase in these risks. Exposure to a heat wave during the last gestational week was also associated with an increased risk of life-threatening delivery complications.

Globally, this summer was the hottest on record. Phoenix broke a record when the temperature topped 110 degrees 31 days in a row. Dozens of other cities including in Texas, Louisiana, and California have experienced their own record-breaking temperature streaks.

While the study did not find significant demographic differences when breaking down the data by race and ethnicity, it did find that people with lower education levels had higher heat-related risk of severe maternal morbidity, said Anqi Jiao, an author of the study. This finding points to possible mitigation strategies that doctors, nurses, and others in public health could take.

“They may pay more attention to these mothers with lower education levels as a targeted intervention,” she said. “Those mothers with lower educational attainment may have very limited knowledge to understand extreme heat as an environmental hazard, and they may not understand why the extreme heat could affect their pregnancy outcome.”

Importantly, the study also found associations between heat exposure and cardiovascular events during labor and pregnancy. Cardiovascular conditions are now a leading cause of pregnancy-related deaths in the United States, a crisis that has only gotten worse in recent years despite medical advances.

Ward applauded the decision to focus on severe maternal morbidity in the study. Other studies have looked at the impact of heat on birth outcomes or maternal health issues like gestational diabetes.

“This is really important because severe maternal morbidity is basically very nearly maternal mortality,” Ward said. “It is the most extreme of health outcomes for pregnant women. And so it’s very serious.”

She points out that it would also be useful if a study like this looked at overnight temperatures, which could further pinpoint what other underlying factors may contribute to heat exposure, she said. “Overnight temperatures indicate maybe a lack of access to cooling at night, where your body doesn’t have the time to recover,” she said, as an example.

Further research could also highlight what kind of exposure people face during the day, related to different socio-economic factors like the type of job a pregnant person has, Ward said.

“A lot of times when we think about occupational exposures we tend to think about men, but that’s just not true. Women work in high-exposure jobs too. They work in the food industry in kitchens that have high heat, a lot of them may be caregivers in an environment in which there is not adequate cooling. A lot of women work in manufacturing, where indoor heat exposure is a thing,” she said. “So it’s about thinking through the underlying factors that are contributing to this.”

Jiao said she and others from her research team plan to look at other temperature metrics in future studies, as well as different climate factors like wildfire smoke.

Ward finds this study to be a significant contribution to our understanding of heat and says it has important implications for emergency planners who can use this research to better understand the dangers of exposure to chronic heat.

“These kinds of studies help inform those kinds of planning and preparedness activities so that they are targeted and that they have the most impact,” she said. “Anytime we get research that helps us understand … the nuances of heat exposure, it helps us protect people better, and that information gets incorporated into the planning and preparedness infrastructure — at least that’s the hope, right?”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Extreme heat is linked to higher risk of life-threatening delivery complications for pregnant people on Sep 16, 2023.

Originally introduced to North America in the 1800s, the European starling is a magnificent bird, tawny brown with white spots in winter, shining with iridescent purple and green feathers in summer.

Not only are they dazzling, since starlings are also some of the most skilled vocal learners, with the ability to mimic the calls of as many as 20 other species, according to Cornell University’s All About Birds.

Starlings learn an impressive variety of calls, warbles, whistles and songs during their lifetimes, a press release from The Rockefeller University said. Besides being superior vocal learners, a new study has revealed that these remarkable birds are also exceptional at problem solving.

“There is a long-standing hypothesis that only the most intelligent animals are capable of complex vocal learning,” said Jean-Nicolas Audet, co-author of the study and a research associate in the laboratory of Erich Jarvis at The Rockefeller University, in the press release. “If that is true, then complex vocal learners should also be better at cognitive tasks, but no one had ever demonstrated that before.”

Complex vocal learning is defined as having the skill to learn and remember a large variety of sounds. Only a small number of animal groups are able to do this, including whales, seals, elephants, bats, humans, parrots, songbirds and hummingbirds.

The research team focused on songbirds, ranking the complexity of their vocal learning using three metrics: whether or not the bird was able to learn new calls and songs through their lifetime, how many calls and songs were in their repertoire and if they were able to mimic other species.

The study, “Songbird species that display more-complex vocal learning are better problem-solvers and have larger brains,” was published in the journal Science.

The researchers spent three years capturing hundreds of wild birds covering 21 species at The Rockefeller University Field Research Center, located on 1,200 acres of protected land that is home to a wide variety of ecosystems in the Hudson Valley.

“It’s a protected area, which means the animals have limited exposure to humans,” said Mélanie Couture, a research assistant who co-authored the study, in the press release. “This is ideal for studying the behaviors of wild birds — what they can do, and how they react to cognitive tasks.”

There were just three types of birds that were able to mimic other species, which Audet said is “the epitome of vocal learning.” They were blue jays, gray catbirds, who are related to mockingbirds, and starlings. The research team ranked these three highest in vocal learning capability.

The team conducted a series of cognitive evaluations on 214 birds of 23 species, including two that had been raised in a lab. The researchers looked at their ability to problem solve by challenging them to pull a stick, pierce foil or remove a lid in order to get to a treat. They also tested for self-control and learning associated with color.

The research team found a strong connection between vocal learning aptitude and problem-solving abilities. Bluejays, starlings and gray catbirds were the best at problem solving, as well as the most adept vocal learners. And birds who were best at navigating around obstacles in order to get to a treat also had more advanced vocal learning ability.

The research team also discovered that birds who were highly skilled problem solvers and vocal learners had larger brains in relation to body size.

“Our next step is to look at the brains of the most complex species and try to understand why they are better at problem solving and vocal learning,” Audet said in the press release. “We have a pretty good idea of where vocal learning happens in the brain, but it’s not yet clear where problem solving occurs.”

The findings of the study suggest that the evolution of problem solving, vocal learning and brain size may have occurred together, possibly in order to boost biological fitness. Jarvis has termed the collection of traits — based on the study’s findings and previous work that assessed how well vocal learners could dance to a beat — the “vocal learning cognitive complex.”

“Our findings help support a previously unproven notion: that the evolution of a complex behavior like spoken language, which depends on vocal learning, is associated with co-evolution of other complex behaviors,” Jarvis said in the press release.

The post Superior Vocal Learning in Birds Linked to Better Problem Solving and Bigger Brain Size appeared first on EcoWatch.

After days of churning in the Caribbean, where Hurricane Lee reached Category 5 status with maximum sustained winds of 165 miles per hour (mph), the storm is headed toward the Atlantic Coast of New England and Canada.

According to the National Hurricane Center, the “large and dangerous” Category 1 storm is projected to make landfall this weekend.

“It’s a batten-down-the-hatches kind of day,” said Kim Gillies, owner of Maine’s Boothbay Harbor Marina, as The Associated Press reported.

Emergency management agencies and the U.S. Coast Guard warned communities in New England to prepare for the storm, as residents removed boats from the water.

Nova Scotia and New Brunswick were under a hurricane watch, while a tropical storm warning was in effect for Bermuda and Massachusetts — including Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket — north to the border of the U.S. and Canada, the National Hurricane Center said.

“Today is the last day to prepare,” meteorologist Stephanie Abrams with The Weather Channel said on CBS Mornings, as reported by CBS News. “Conditions go downhill tonight, and tomorrow, Lee will be battering parts of New England. The strongest winds are expected to be along the coast.”

The National Hurricane Center predicted the southern portion of New England would start seeing tropical storm conditions, including flooding along the coast, this afternoon. Lee was expected to make landfall in Canada on Saturday.

Most of Maine is currently under a tropical storm warning, Portland, Maine’s WMTW News reported. The storm currently has maximum sustained winds of 80 mph, the hurricane center said.

“The winds will increase through the day today, and tomorrow gusting as high as 75 mph,” Abrams said, as reported by CBS News. “Sunday, they’re going to start to taper off from the south to the north.”

More than three million people were under warnings and watches, Abrams said.

New England is still dealing with the aftermath of stormy weather that brought heavy rain, flooding and tornados, The Associated Press reported.

Tide and storm surge from Hurricane Lee are expected to cause more flooding along the New England Coast, reported NBC News. Forecasters said Cape Cod, Boston Harbor, Long Island Sound and other coastal areas were expected to get one to three feet of flooding, with one to two feet in parts of New York.

So far there have been five hurricanes and 14 named storms in 2023. Last month the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) said atmospheric and ocean conditions like record warm temperatures were expected to contribute to an “above normal” hurricane season.

“NOAA forecasters have increased the likelihood of an above-normal Atlantic hurricane season to 60% (increased from the outlook issued in May, which predicted a 30% chance),” the agency said in a press release issued last month.

The post ‘Large and Dangerous’ Hurricane Lee Heads for New England and Canada appeared first on EcoWatch.

Hurricane Lee, a mammoth peak-season storm in the Atlantic, is making a beeline for New England and Canada. Once a Category 5 storm, Lee weakened to Category 1 by the time it made a northward pivot and began its march toward land on Thursday. But the storm is still expected to lash parts of Massachusetts, Maine, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia with tropical-storm-force winds, rain, waves, and potentially catastrophic storm surge as it makes landfall over the weekend.

Meteorologists are especially concerned about the Bay of Fundy, a body of water between eastern Maine and Nova Scotia that holds the record for the highest tides in the world — with a difference of up to 53 feet between low and high tides. With a little bit of bad timing, Lee’s powerful winds could force a tremendous amount of water into the bay on top of a high tide, and inundate New Brunswick and Nova Scotia with record flooding.

Even on an ordinary day, the Fundy tides are so dramatic that they can sweep over whole beaches in a matter of minutes. In some parts of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, the incoming water at high tide pushes so far inland that it reverses the flow of rivers, a phenomenon known as a tidal bore.

“If the storm goes just west of the Bay of Fundy, and it’s aligned with the correct tide cycle — well, it’s an unfortunate science experiment,” said Jeff Berardelli, chief meteorologist for WFLA-TV in Tampa Bay, Florida. “We’ve never seen something like that exactly.”

Lee’s winds will be blowing west, which makes Nova Scotia, on the east side of the Bay of Fundy, particularly vulnerable to rising waters. There, waves could reach 40 feet in height on top of three to six feet of storm surge. “The water impacts, just exactly what’s going to happen there, that’s the big question mark,” said Ryan Truchelut, a meteorologist and the founder of the weather Substack WeatherTiger. “That’s potentially the most serious aspect of the storm.”

Storm surge could also be an issue on the north-pointing part of Cape Cod, Massachusetts. The National Hurricane Center has issued a storm surge watch for that portion of the cape.

Sixty-four-year-old Howard Zwicker owns the Harbour Grille & Gift House on Grand Manan Island, a small Canadian island between Maine and Nova Scotia at the wide mouth of the Bay of Fundy. On Thursday morning this week, he was unruffled by the forecast. “We’re cleaning up our yard, taking down our hanging plants and our patio furniture, and that’s pretty much it,” said Zwicker, who was born on Grand Manan Island and has run the Harbour Grille with his wife for the past decade. “Everybody is doing their due diligence, but nobody’s panicking.”

Storms of Lee’s intensity are not unusual in the northern Atlantic, though they rarely make landfall in New England and coastal Canada. Lee’s impacts will also be abnormal in a couple of respects. It’s a large weather system — the hurricane’s tropical force winds span roughly 600 miles in diameter — which means its effects will be felt in multiple states along the Eastern Seaboard.

“It’s gigantic,” said Truchelut. “In terms of tropical storm wind radii, this is one of the very largest out there.” Much of coastal New England will experience huge, battering waves that are 15 feet or higher. On Thursday, the governor of Maine issued a state of emergency as the state was put under its first hurricane watch in 15 years.

The other unusual thing about Lee is that the storm will bring flooding to a part of the U.S. that is already waterlogged from a summer so rainy it broke records in parts of New Hampshire and Vermont. This summer was Maine’s second wettest on record, behind the summer of 1917. Record-breaking rainfall is a telltale sign of climate change; research shows a hotter atmosphere holds more evaporated water.

Flooding brought on by Lee on top of the already soaked soil in New England will make the storm’s impacts more dangerous. Heavy gusts of wind can cause trees rooted in saturated soil to tip over, and localized flooding is more likely. “Fifty- or 60-mile-per-hour winds, you get that every year,” Truchelut said. “The difference here is that the trees still have their leaves on, and the soil is wet from recent rainfall.”

Climate change doesn’t create large hurricanes like Lee, but it does make them intensify faster and occur more frequently. The Atlantic Ocean is currently going through a period of extreme sea-surface warming — water temperatures in parts of the North Atlantic have hovered around 77 degrees Fahrenheit for more than a month, “almost beyond the most extreme predictions of climate models,” the Washington Post reported in July. That record warmth allowed Hurricane Lee to intensify from a tropical depression to a Category 5 storm in less than three days, a phenomenon that has only happened a couple of times before in Atlantic hurricane history.

“Given the record-high sea-surface temperatures in the North Atlantic, it is interesting that in this year we see a hurricane barreling toward New England,” said Sean Birkel, the state climatologist for Maine. “Because it is rare for hurricanes to reach New England and certainly into Maine.”

Lee is arriving at the meteorological midpoint of hurricane season, and there are multiple other storm systems on its tail. These include Margot, which is churning in the middle of the Atlantic, and a still-forming storm that could become Hurricane Nigel. Forecasts show Nigel taking the same path as Lee, west across the Atlantic Ocean and up past Bermuda. Even if the Northeast escapes major damage from Lee, it may not be out of the woods yet.

Jake Bittle contributed reporting to this article.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline ‘It’s gigantic’: Hurricane Lee heads for New England and Atlantic Canada on Sep 15, 2023.

The Climate Prediction Center (CPC), part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) National Weather Service, has issued an El Niño Advisory that predicts an over 95% chance that the El Niño climate pattern will continue through winter to March 2024.

“In August, sea surface temperatures (SSTs) were above average across the equatorial Pacific Ocean, with strengthening in the central and east-central Pacific,” CPC said in a statement.

In its notice, the CPC said that the likelihood of a “strong” El Niño is now 71%, although it explained that a stronger El Niño doesn’t always lead to strong local impacts. However, this climate pattern can impact different regions in varying ways.

“As El Niño strengthens to strong status, there is a good likelihood it will have an impact on the upcoming growing season for the southern hemisphere crop production areas,” Chris Hyde, a meteorologist at Maxar, a space-technology company, told Reuters. “This includes crops in South Africa, Southeast Asia, Australia and Brazil where the weather is typically drier and warmer than normal.”

During an El Niño event, trade winds are weaker, and warmer water moves east toward the Pacific Coast of the U.S. This typically causes warmer, drier conditions in the northern U.S. and Canada and wetter conditions in the southern U.S., NOAA explained. However, no two El Niño events are the same, and they can bring different impacts around the world.

El Niño events usually happen every 2 to 7 years and last for 9 to 12 months. As The Weather Channel reported in June 2023, the current El Niño episode arrived earlier this year, and at the time had a 56% chance of becoming a strong El Niño event.

By July, the World Meteorological Organization warned that this year’s El Niño may lead to record-breaking temperatures and extreme weather. The last strong El Niño event happened in 2016, the hottest year on record.

The WMO previously predicted El Niño had a 90% chance of continuing with at least moderate strength through the end of this year.

The average sea surface temperatures in the Pacific Ocean has been higher than usual for August and up from July, when the global sea surface temperature average reached a record high. “The global climate models we rely on are pretty certain that the currently observed warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures will last and even strengthen through winter 2023–24,” wrote Tom Di Liberto, writer for Climate.gov. “After which, this El Niño event is expected to weaken, which is normal for these types of events.”

The post El Niño 95% Likely to Continue Through March 2024: Climate Prediction Center appeared first on EcoWatch.

Owen Barrett, cofounder and president of Rayven, is working to make it easy for individuals…

The post Earth911 Podcast: Rayven CEO Owen Barrett on Electrifying the Nation’s Apartment Buildings appeared first on Earth911.

Today’s inspiration is from scientist, teacher, and writer Aldo Leopold, considered by many to be…

The post Earth911 Inspiration: A Community to Which We Belong appeared first on Earth911.

Tucked deep within President Biden’s landmark climate bill sits a seemingly small tweak to IRS rules that, for the first time, lets companies sell their clean energy tax credits.

The change accounts for just a fraction of the 100,000 or so words in the Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA, which Congress passed in 2022. But experts say that by making clean energy tax credits more accessible, the move will help drive most of the government’s investment in the sector over the next decade and supercharge the industry.

“It’s pretty unprecedented,” said Jorge Medina, an attorney who specializes in renewable energy and tax policy at the firm Shearman & Sterling. “There hasn’t been a program quite like this, and not on this scale.”

After President Biden signed the IRA into law last summer, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that its tax credits would account for roughly three quarters of the legislation’s $369 billion in climate incentives. When the treasury department released its proposed transferability rules in June, Secretary Janet Yellen called the mechanism a “force multiplier.”

The IRA provides tax credits for a range of clean energy technologies, from the deployment of solar and wind to the development of clean hydrogen and carbon-capture projects. But these benefits can only be used to offset tax liabilities, which many startups or projects may not have until they begin earning profits.

Before the IRA, clean energy developers got around this by creating a legally complex “tax-equity” partnership, said Rachel Chang, a policy analyst at the Center for American Progress. That, however, often sidelined smaller players because with only so much tax liability to go around, investors often focused on more lucrative projects.

“The tax-equity market has been to some extent what’s holding renewables back,” said Medina.

The IRA made capitalizing on these incentives much easier. Now, a developer who doesn’t have a tax liability can sell their credits to a company that does and get cash to help fund its project. While credits can only be transferred once, Medina and others still anticipate that this streamlined process will make developing clean energy more appealing.

Interest has already proven so great that in June, the Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation estimated that the credits will be worth $663 billion by 2033 — about 250 percent higher than the Congressional Budget Office’s earlier projection. On the anniversary of the IRA, in August, Bank of America made the first public announcement of a transfer deal when it agreed to buy $580 million in wind energy tax credits from renewable power developer Invenergy.

The burgeoning market has also created an industry of connecting tax-credit buyers and sellers. “There’s a niche market of brokers that has grown since the IRA started,” said Medina. “There are probably dozens of them.”

Crux is among the companies that has stepped into this new sector. It has raised $8.85 million in capital for a software platform that helps buyers, sellers, and intermediaries navigate the often complex bidding process, paperwork, and regulatory requirements associated with the transfers.

“These are simpler transactions than tax equity, but they aren’t simple,” said co-founder and CEO Alfred Johnson, who was previously deputy chief of staff to Yellen.

One of the biggest potential chokepoints, Johnson said, will be ensuring there are enough buyers for the anticipated surge in the supply of credits. While demand has so far come from traditional players in the tax-equity space — like big banks — he “increasingly sees new buyers come to the market,” and Crux claims it is already helping facilitate more than $1 billion in deals.

The credits generally are sold at slightly less than face value. Medina says prices have varied depending on the credit in question and how risky a project is, but they typically go for about 85 to 95 cents on the dollar.

A related change in the tax code under the IRA allows tax exempt entities such as nonprofits or state and local governments to skip the transfer market entirely. Instead, the government pays them 100 percent of the credit directly.

“It’s pretty revolutionary,” said Jillian Blanchard, the director of the climate program at Lawyers for Good Government. Her team is encouraging eligible organizations to take advantage of this windfall, and educating them on the process. “It’s finally becoming available to public entities and tax exempt entities in a way that can be game changing.”

Neither of the new tax changes, however, are perfect. One issue for tax exempt entities, Blanchard said, is that the treasury’s proposed rule doesn’t allow them to claim the credit when they work with one another, which could be beneficial. For example, if a town and a local renewable energy nonprofit collaborate on a solar project.

As far as the tax credits go, some in the tax and clean energy sectors have argued that individuals — and not just corporations — should be able to purchase them, which would further expand the pool of buyers. The final version of the rules, expected this fall, could incorporate some of these changes.

One concern that the changes are unlikely to fix, however, is that the tax-credit transferability could subsidize companies outside the climate sector, including those that are driving greenhouse gas emissions. “Some of the tax breaks may go somewhere that policymakers never wanted,” said John Buhl, an analyst at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. “There’s nothing to stop oil companies, or particular types of businesses, from buying these assets.”

Overall, though, experts say the newfound ability for companies to transfer tax credits appears to be on track to meet its objective of rapidly getting more clean energy out into the world.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline This tax tweak is supercharging Biden’s climate agenda on Sep 15, 2023.