Chantell Dunbar-Jones remembers when her hometown of Lewisville, Arkansas, seemed to have oil wells on every corner. The small town, located in the southwestern part of the state, sits atop the Smackover Oil Formation, one of the largest oilfields in the United States. For a long time, nearly everyone worked for the oil industry. Dunbar-Jones’ father started with Phillips 66 but was shunted to smaller and smaller companies as wells started closing in the late 1990s and the industry shifted toward Texas. In the years since, the town has seen residents and businesses leave in pursuit of brighter futures.

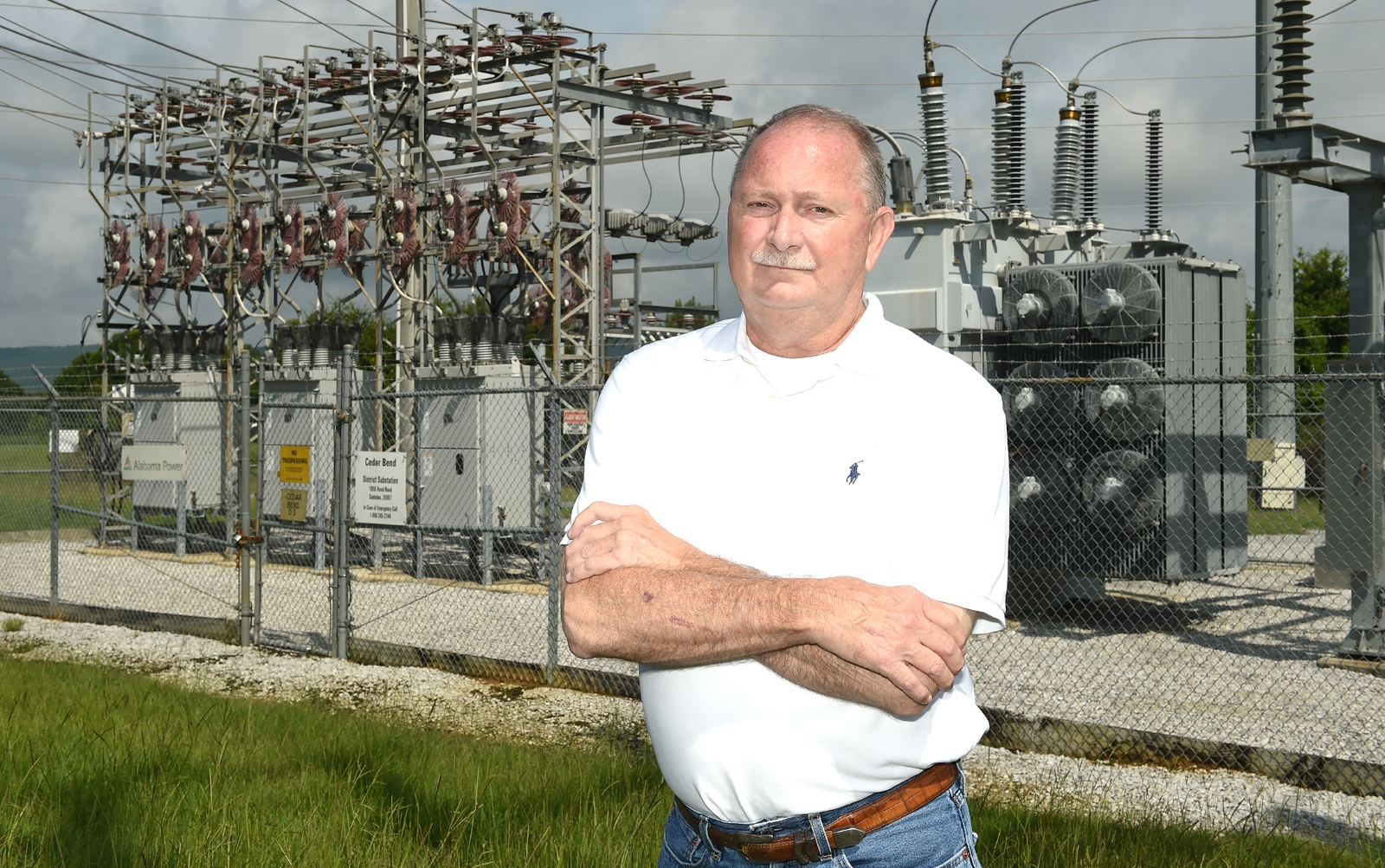

The area’s fortunes began to look up late last year, when ExxonMobil, alongside a couple of other companies, announced its intention to begin producing lithium in the region by 2027. It opened a test site on the Smackover formation, which spans three states and could supply 15 percent of the world’s lithium. It’s got folks in Lewisville cautiously hopeful that the change could turn things around.

“We are just very excited, trying to get all our ducks in a row and be able to take advantage of what’s coming,” said Dunbar-Jones, who has served on the city council for seven years.

ExxonMobil joins a growing rush to supply the natural resources needed to drive the green transition. Oil producers and coal companies like Ramaco Resources are looking to collaborate with the Department of Energy to uncover them and, in some cases, wring more money from land they already own.

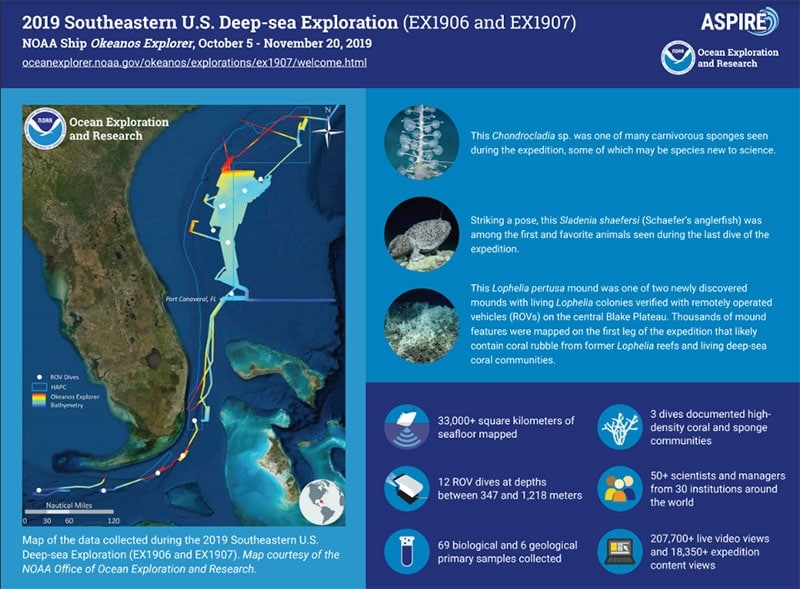

Lithium and other minerals like cobalt, nickel, and silicon are essential to producing solar panels, wind turbines, and the batteries that power electric vehicles. Right now, the vast majority of these critical minerals come from Argentina, Australia, Chile, China, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. There’s only one rare-earth elements and one lithium mine in the U.S., and the Biden administration has made more than $407 million available for domestic exploration and production through the Inflation Reduction Act. That influx compounds the effect of other investments at various links in the domestic clean energy supply chain. These subsidies have made cashing in on the green transition attractive to fossil fuel companies, many of which have access to potentially productive land and the experience and equipment to mine it. In places known for their reserves of oil and coal, such as the Powder River Basin of Wyoming and southern Arkansas, fossil fuel companies are descending on newly discovered stores of critical minerals. That’s left some people excited by the promise of economic revitalization and others nervous that they’ll be revisited by all the worst social and environmental impacts of fossil fuel extraction.

Dunbar-Jones, so far, sees few reasons for concern. Mostly, Exxon’s announcement, alongside similar announcements from companies like Standard Lithium, feels like a great excuse to dress up Lewisville and collaborate with surrounding towns to open the region up for business. She’s been told the area could see hundreds of new jobs. “We’re losing people to lack of adequate housing, lack of adequate employment,” she said. “Now that lithium is coming, everyone’s trying to come back.”

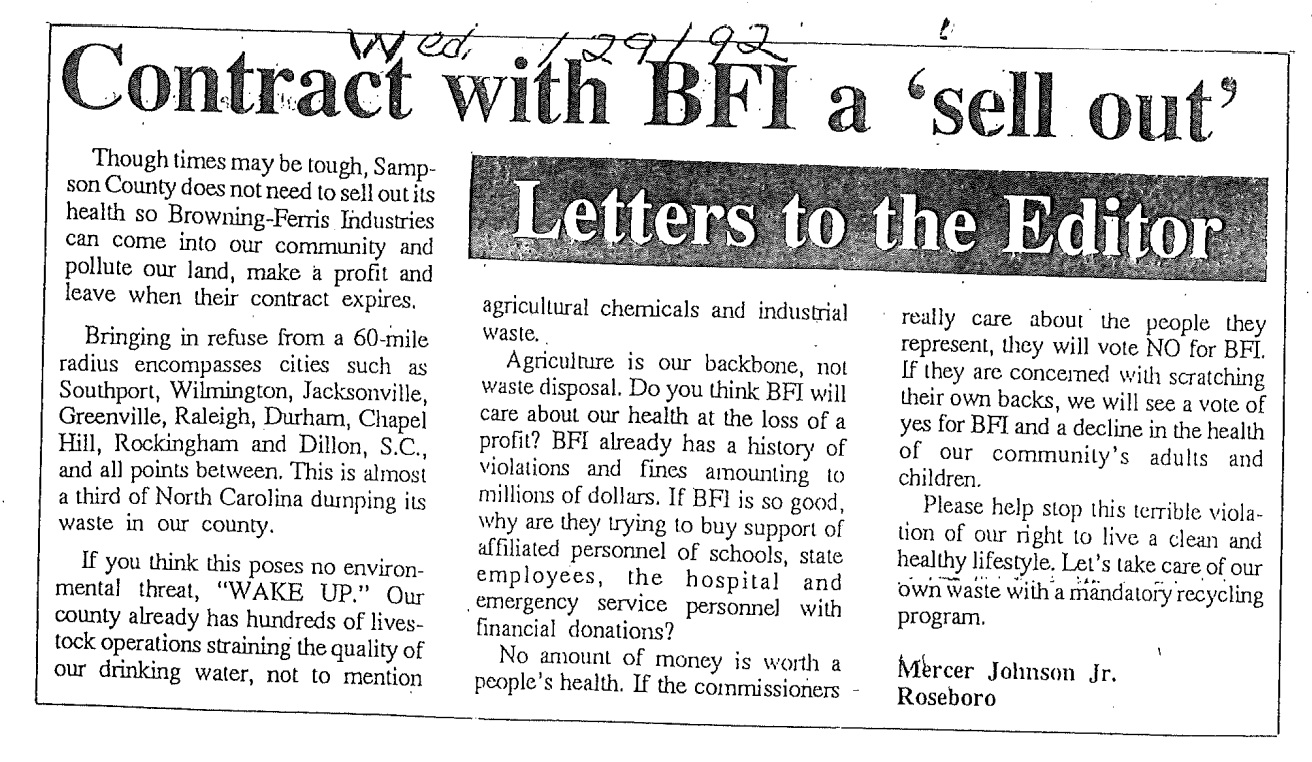

The land around the Smackover Oil Formation remains scarred by years of eager and often ill-planned petroleum extraction, its streams contaminated by oil and brine. Exxon and other companies looking for lithium have participated in public meetings where they’ve allayed environmental concern, Dunbar-Jones said, declaring their methods to be safe and environmentally sound. But she still wonders.

“How can you really know before they come in and get started?” she asked.

ExxonMobil did not respond to a request for comment, but in a statement announcing the lithium project said the process by which it will mine the lithium is safe and produces fewer carbon emissions than hard rock mining and requires significantly less land.

Critical minerals extraction is subject to a relatively loose framework of regulations, and it can be quite destructive, said Marco Tedesco, a climate scientist at Columbia University who has researched its extraction worldwide. To exploit the Smackover formation, Exxon plans to tap the lithium-rich brine 10,000 feet below ground using a process called deep lithium extraction. “They pump lithium from the bottom — similar to fracking,” Tedesco said, adding that the process requires an immense amount of water. The brine evaporates, leaving lithium salts and other byproducts, some valuable and some toxic. “People living by a mine, they have a right to exploit this economic opportunity,” he said, but in practice, Tedesco sees most of the benefits leaving the communities where extraction happens.

“Unfortunately, history is scattered with a systematic disregard for transparency and a lack of accountability by corporations,” Tedesco said.

Water scarcity is a big topic in Wyoming, a cold, dry state with expansive strip mines, intensive fracking, and a growing industry in critical minerals. Coal has been tied to the identity of Gillette, a small town in the northeast corner of the state, for over 100 years. The Powder River Basin holds most of the nation’s recoverable reserves. Coal company Ramaco Resources, with the help of a Department of Energy national laboratory, discovered what may be the nation’s largest deposit of rare-earth metals on land it bought for $2 million in 2011. Rather than dig for coal, Ramaco will tap what it says will be a $37 billion bonanza in critical minerals.

Shannon Anderson, the staff attorney for the environmental organization Powder River Basin Resource Council, doesn’t see anything unusual in what Ramaco is doing. “Companies are really good at reinventing themselves when there’s a market opportunity to do that, ” she said, and the mining industry has been eager to join the clean energy supply chain. Research has shown that mine tailings, acid mine drainage, and other toxic coal waste may in fact be a decent source of critical minerals. Despite his opposition to many of President Joe Biden’s clean energy policies, Senate Democrat Joe Manchin, who represents the coal-producing state of West Virginia, had little trouble pushing to bolster domestic critical minerals supplies, in hopes that might make mine waste profitable for coal companies. What has changed in Anderson’s 16 years of work are “the astronomical level of subsidies that are driving these decisions.”

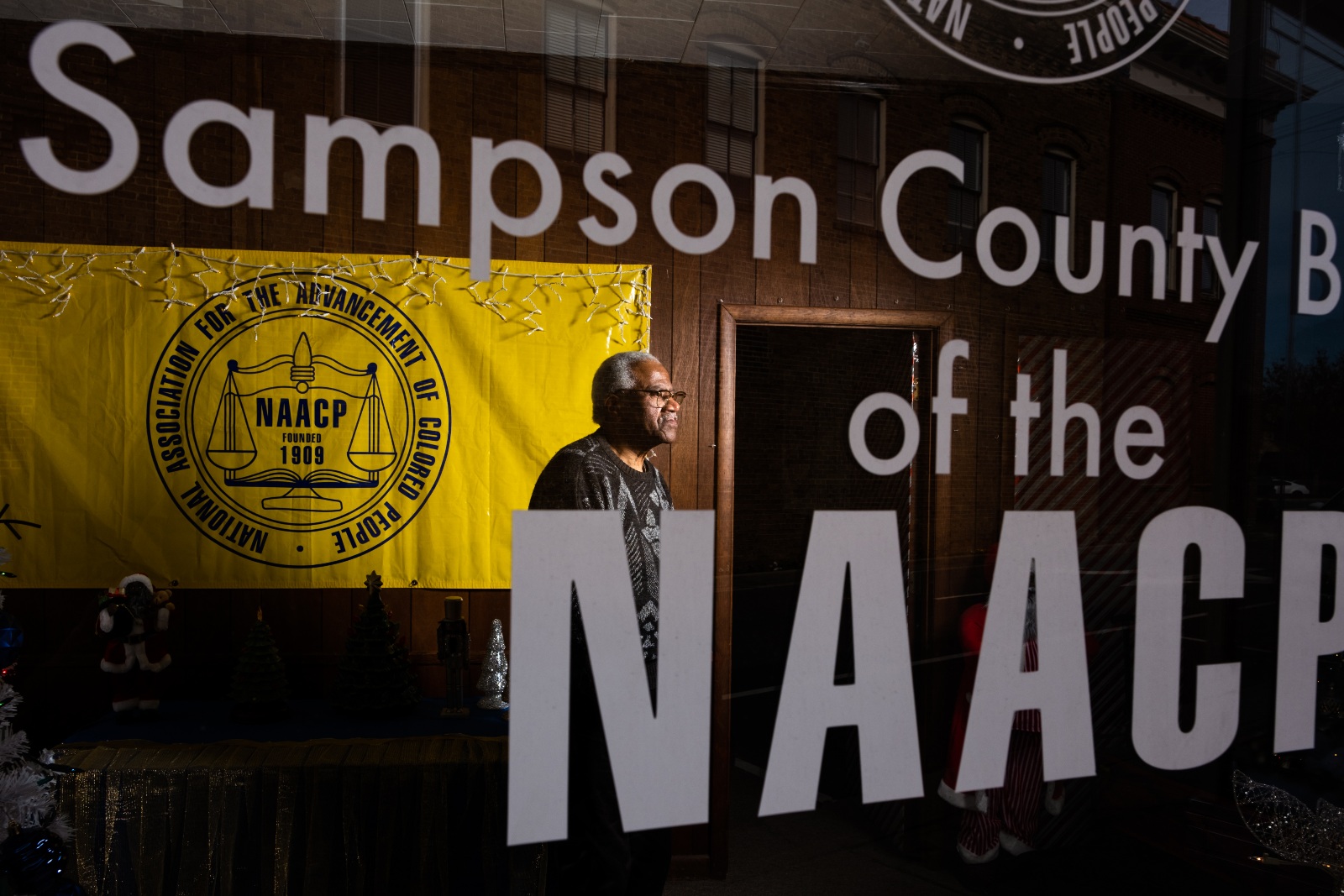

In Wyoming, grassroots organizations and the communities they serve are particularly concerned about water consumption and pollution, both ongoing problems in the state’s high deserts. “We’ve been dealing with the impacts of coal for a long time,” Anderson said. “Are we ready to deal with the impacts of new kinds of mining for a generation or two?”

Anderson also expressed concern that the Biden administration’s goodwill toward “energy communities” — defined as those regions once dependent on fossil fuels and faced with diversifying their economies — could result in further exploitation in those communities, which Biden has made a priority for investment through clean energy programs.

While many federal grants and loans focus on improving housing, broadband, and energy efficiency, a few focus on mineral research, biofuels, and natural gas infrastructure. Since January 2021, the Department of Energy has announced an estimated $41 million in projects to support critical minerals exploration in former mining communities.

Despite these funding opportunities, many of these places may fall short when it comes to tax revenue, environmental regulations, and cleanup. Laws vary from state to state, but most of the places that saw a massive resource wealth extracted by coal and oil companies received only a small percentage of that windfall through wages, state royalties, local severance taxes, and company largesse like building parks or other amenities.

The severance taxes on critical minerals, which fall under the “general minerals” tax category, are in general lower than those paid on coal and oil. Under the 1872 mining law, they don’t yield state royalties at all. For that reason, ensuring communities see a financial benefit requires rethinking how those revenues are shared. “You can’t design a tax system to do a one-for-one replacement,” said Anderson.

The 1872 mining law also doesn’t apply to private land or land east of the Mississippi River. That land is instead regulated by the Clean Water Act and other laws, and by permitting processes that are looser than those for oil and coal. Within this patchwork of federal, state, and local laws and land ownership schemes lie many loopholes for some kinds of mining waste. Blaine Miller-McFeeley, a mining expert at the environmental law nonprofit Earthjustice, cautioned that there are many ways for oil and gas companies to evade responsibility for the long-term effects of mineral mining.

“The current administration is not applying strong enough diligence standards to money that’s going out the door,” Miller-McFeeley said. ”They have the opportunity to set a high bar so that we are not moving our sacrifice zones from oil- and coal-impacted communities to mining-impacted communities.”

“These oil and gas and coal companies are greenwashing themselves,” he added, “by saying the way they’ve always done mining, which is the destructive, toxic way, is the solution to climate change.”

The Biden administration has noted these challenges, and an Interior Department interagency working group is attempting to reform the 1872 mining law to allow for more stringent environmental regulation and public process — though mining industry representatives and Republican officials have criticized these efforts, and they are currently stalled. Environmental Protection Agency officials contacted by Grist affirmed broad support for a new, tightly regulated leasing system that allows the U.S. to meet increased critical minerals demand with greater attention to water quality and communities’ rights to say no to new development, or if the development is wanted, maintain transparent communication with mining companies.

Ramped-up regulation, Marco Tedesco said, could help ensure the communities that provide the materials needed to wean the country off of fossil fuels see more of the benefits, and fewer of the problems, that fossil fuel extraction brought them. But he cautioned that will happen only if rural, working-class communities like Lewisville and Gillette are involved in a public and transparent process to shape the policies needed to do that.

“Involving communities at decision level in the early stages, investing in addressing environmental impacts, projecting the consequences on future generations, and sharing the economic and financial benefits with the communities should be moving together,” Tedesco said, “like the elements of a choir.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Oil companies used to run this town. Now they’re back — to mine for lithium. on Jan 22, 2024.