This story was produced in partnership with The Desert Sun.

Andy Domenigoni is no stranger to wildfires.

On an October day in 1993, the rancher was on horseback herding cattle in the Southern California community of Winchester when what would become a 25,000-acre wildfire tore through the brush-filled hills. The fire blocked the route to his ranch, but he found a clearing and hunkered down for the night, emerging to find the area transformed into a “moonscape.”

“But hey, you rebuild or you move away. You only have a couple of choices,” said 72-year-old Domenigoni, whose family was among Winchester’s first settlers in the late 1870s.

A decade later, that experience didn’t stop Domenigoni from developing thousands of homes on the family’s acreage. A plan for about 4,000 homes on the ranch was approved back in 2004, but put on hold “waiting for the economy to improve.”

The time is now, Domenigoni says. The median home price in California is hovering around $800,000, and as the state’s housing crisis pushes people inland in search of something they can afford, developers are taking an interest in this sparsely populated pocket of the Inland Empire, 80 miles from Los Angeles.

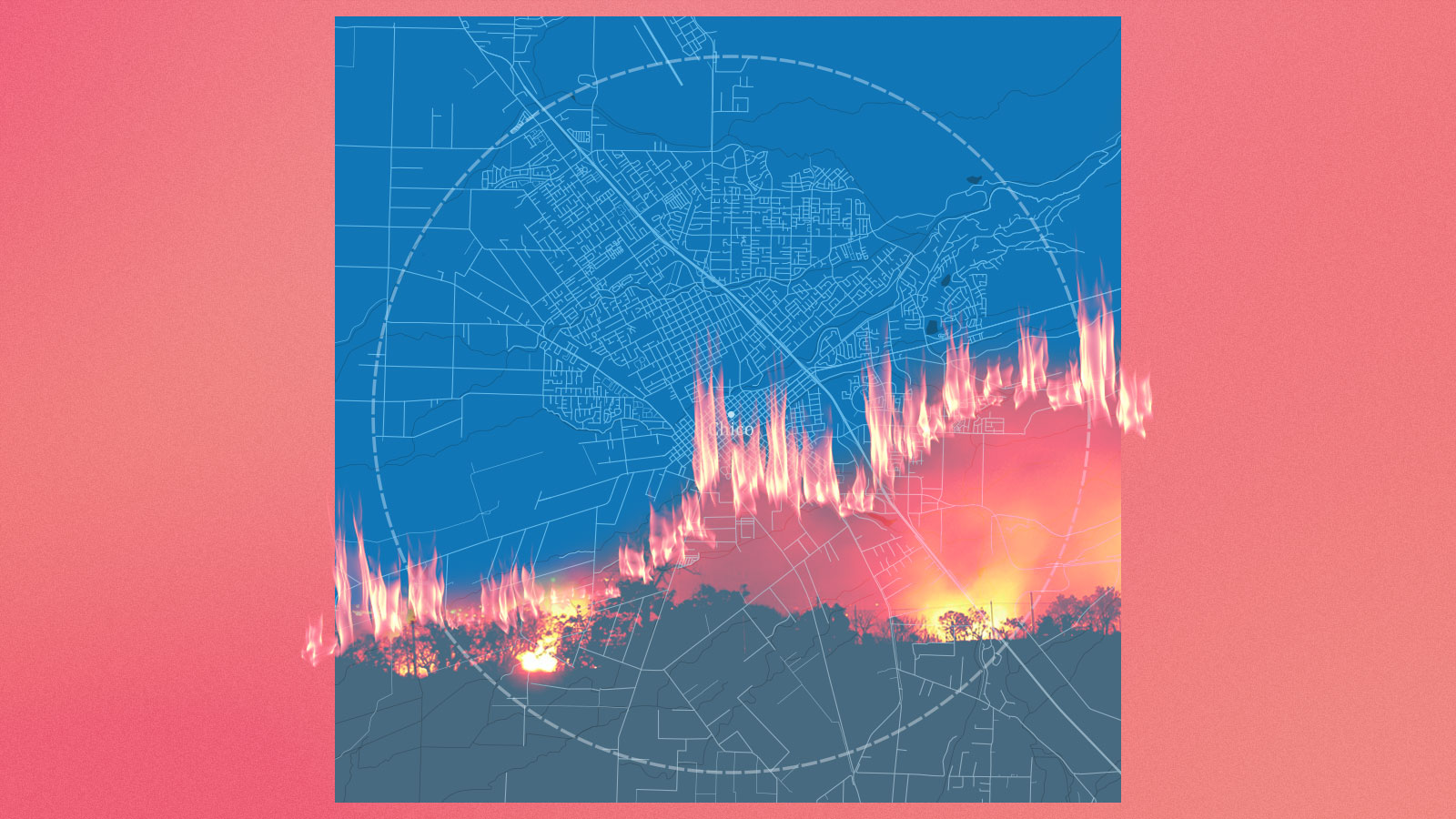

Once tract maps are approved to subdivide Domenigoni’s land, the 4,000 planned homes will join more than 7,500 others that are either built out, under construction, or in earlier development phases in Winchester, many of which are in the state’s “very high” or “high” fire hazard severity zones. And Riverside County’s planning documents for Winchester anticipate thousands more.

The seeds for these developments, planted years ago, are starting to take root.

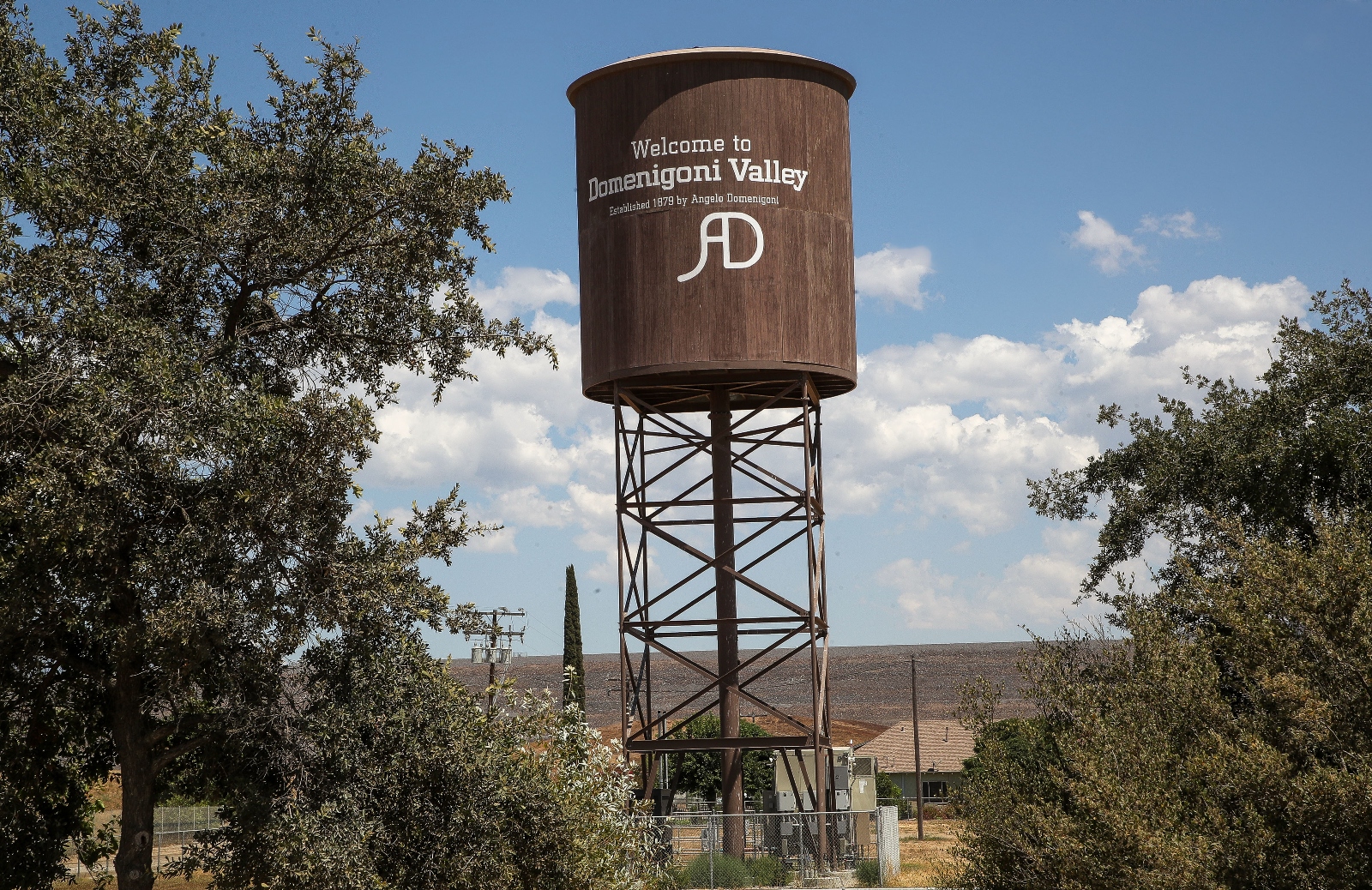

The area’s dry chaparral valleys, which were all but empty just a few years ago, have begun filling up with hundreds of new tract homes that sit nestled between steep hills. As you drive along Domenigoni Parkway, a thruway named for Domenigoni’s ancestors, you can see clusters of homes spreading out in every direction, as well as graded pads and construction sites that foreshadow hundreds more.

The early stages of Winchester’s development boom began around the early 2000s, when new infrastructure like Domenigoni Parkway paved the way for housing development in the rural area.

Andy Domenigoni holds a photo of his great-grandfather, one of the first settlers of Winchester, California. A sign on a tower welcomes people to the Domenigoni Valley and notes its establishment in 1879 by Angelo Domenigoni. Along Domenigoni Parkway, a sign advertises newly built homes. Jay Calderon / The Desert Sun

“The groundwork for homes was already laid, whether you liked it or not,” Domenigoni said. “If you were a person that was sitting on 10 acres, five acres, or one acre, [developers] went in and bought them up from landowners who wanted to get out or wanted to sell their property.”

Most of these developments are tracts of just a few hundred homes. Builders have snapped up tract maps approved in 2004 and 2005 in areas prone to wildfires and each built hundreds of homes across the formerly empty landscape over the past few years, as the demand for housing rose.

The homes could look like a welcome oasis for homebuyers in a state in the throes of a housing crisis driven by years of lackluster housing production. For potential homebuyers from the more expensive Orange, San Diego, and Los Angeles counties, the ability to buy a new home in the $400,000 to $500,000 range is tempting enough to uproot from their communities and move to Riverside County, even while maintaining lengthy commutes to their jobs elsewhere.

But these idyllically named subdivisions like Lennar at Prairie Crossing, Tri Pointe’s Opal Skye at Outlook, and D.R. Horton’s North Sky are all in a zone that the state of California has classified as one of the riskiest parts of the state. A series of brush fires have torn through the area in recent years, igniting on dry grass and sweeping over hills before firefighters tamped them out. In the afternoon, strong winds rush down from the hills and into the new subdivisions.

While most California counties lost population in 2022, more people moved into Riverside County than anywhere else in California. Unincorporated Riverside County added the fifth-most new housing units out of all California municipalities that year, trailing only the more urban areas of Los Angeles, San Diego, Oakland, and San Francisco. And Riverside County cities often rank among the fastest-growing in California by population and housing units, as new housing developments pop up in the foothills to absorb the region’s growing population pushed out from more expensive coastal areas.

As Riverside County grows, the number of homes in the wildland-urban interface is growing, too. Between 2000 and 2020, the number of homes in these zones grew by over 165,000 units, according to data from the University of Wisconsin-Madison SILVIS Lab.

Housing in areas with high wildfire risk has become so common in Southern California that some residents are simply trading one risky area for another. Karen Maceno evacuated her previous home in San Diego County twice during wildfires before relocating to Winchester to be closer to her grandchildren. She’s intimately familiar with the experience of evacuating a brand-new home, and keeps an eye out for fires in the hills directly behind her home, but feels safer in new tract housing with easier access to main roads than she did tucked away in a San Diego canyon.

“That was a brand-new gorgeous home, and you just don’t think, ‘God, this area is going to burn,’” Maceno said. “And of course, the weather has changed, it’s a lot drier and hotter. I’m always watching for smoke, but I feel less concerned because of what we’ve already been through.”

Winchester is only one example of a place where California’s climate and housing crises are converging, as the state grapples with a need for more housing development and wildfires that are increasing in frequency and intensity due to climate change. While the past few years have seen a series of highly publicized lawsuits over large developments in wildfire-prone areas, smaller developments have exploded in places like Winchester with little fanfare.

Over the past two decades, as new construction has sprawled from major cities, an increasingly large share of new housing has appeared in risky areas like the fire-prone Inland Empire. In Southern California, as in other places around the country, developers are building millions of homes in areas that are vulnerable to climate disasters that include wildfire, flooding, and drought. More than 12 million new homes appeared in the wildland-urban interface between 1990 and 2010, and millions more have gone up in flood zones and coastal areas. Developers have spread out over slopes covered in flammable brush, built subdivisions right up against creeks and bayous in Texas, and flocked to the Florida shoreline.

The reasons why are many.

Some homeowners seek out risky areas like beachfronts and mountain forests because they like waterfront views or forest seclusion. Other people can’t afford to live anywhere else, so they move out to cheaper areas farther from big cities. Developers also choose to build in these far-out areas in order to avoid high construction costs and zoning laws that make building difficult: A recent paper from an economist at the University of California, Los Angeles, found that strict zoning laws in San Diego have caused at least 7 percent of the population growth in surrounding fire-prone areas. Finally, state and federal subsidies tamp down the cost of dealing with fires in these vulnerable areas, masking the true cost of living near wildfire danger.

This complex web of policies has put millions of future homeowners in the path of wildfire, ensuring that many of them will experience future displacement and financial loss when blazes destroy their homes. Policy experts say that unwinding it will require not just changing laws and policies in places like Southern California, but also rebalancing whole housing markets to incentivize the dense, resilient construction that isn’t happening now.

“When you have what appears to be a significant magnitude of risk, but there’s a very low probability of it happening in any given year, it feels to people like it’s not going to happen to them, and there’s no incentive not to build,” said Sean Hecht, a law professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, and an attorney for the environmental nonprofit Earthjustice. “There’s still a market for housing everywhere, and I don’t see much movement to slow it down.”

Jay Calderon / The Desert Sun

If you want to understand why so many homes are appearing on Domenigoni Parkway, it helps to start almost a hundred miles west of Winchester, in Los Angeles. Many of the people who live in subdivisions like Prairie Crossing commute to the Los Angeles area for work every day, burning millions of gallons of gasoline a year, yet builders like Lennar and Horton choose to build out in the empty desert, rather than in the city.

No one understands the reasons why better than Ted Handel.

Back in 2016, before the rush of sprawl development had arrived in Winchester, Handel took the helm of an affordable housing development company called The Decro Group. His first project was to build an apartment complex on a large lot just west of downtown Los Angeles, but it wasn’t long before he ran into problems. The street he wanted to build on was unusually narrow, which made design for the 64-unit project much more expensive. There was a historic house on the lot that Decro had to move, plus an abandoned oil well underneath the property that he had to plug. He managed to raise millions of dollars for the difficult construction job, but then he ran into trouble with nearby residents who thought the six-story building was too tall.

In order to get the project approved, Handel had to spend months wooing both the area’s neighborhood council and the Los Angeles city council. Even once he did that, he faced procedural appeals from neighbors who argued that the building would block their view of the sky and make traffic worse. The project finally opened up last year, seven years after Handel started on it, with rents capped at around $1,470, well below average.

It sold out almost at once.

Los Angeles is in dire need of more housing: Around half of all households in Los Angeles County are housing-burdened, which means they spend at least 30 percent of their income on rent or mortgage payments, and a recent report from the real estate website Zumper found that the city has the eighth-highest median rent in the United States. But building more housing in the city is almost impossible: In the time it took Decro to build 64 apartments in downtown Los Angeles, builders stood up hundreds of homes in Winchester alone, laying out streets and water mains on empty desert.

The biggest reason why so much construction happens in the wildland-urban interface is that it’s far more expensive and time-consuming to build “infill” housing in dense areas like Los Angeles than to throw up new homes on vacant land. Even if a developer can find the money to finance a large building like Decro’s project in Los Angeles, getting permission to build it is another matter altogether: Most cities have strict zoning laws that regulate what developers can build on any given block, and these laws often prohibit any kind of multifamily development.

A sign welcomes visitors to Winchester, California. A new McDonald’s under construction on Domenigoni Parkway in Winchester, as seen on August 14, 2023. Jay Calderon / The Desert Sun

Local opposition doesn’t help. As millions of people have flocked to cities like Los Angeles and San Francisco, homeowners in those cities have tried to block new development by protesting at community meetings and taking developers to court. These anti-development activists have come to be known as NIMBYs, an acronym for “not in my backyard.”

A landmark 1970 law known as the California Environmental Quality Act, or CEQA, which gave Californians a legal weapon to fight harmful industries like manufacturing and petrochemicals, also made these NIMBY challenges easier by opening up lawsuits over almost any kind of “environmental impact,” including construction noise and shadows. This dynamic played out recently at a development in L.A.’s Los Feliz neighborhood: Developers wanted to build 96 apartments on the former site of a gas station, but neighbors held up the project by petitioning the city to block it, arguing that the building was “completely out of character and style for the neighborhood” and would worsen traffic. It took the better part of a decade to finish it.

“You can go through 10 years of brain damage trying to build an apartment building in San Francisco,” said Jenny Schuetz, a senior research fellow at the Brookings Institution who studies urban economics. “You can go out into undeveloped areas and build a single family subdivision in half the length of time.”

These regulatory and economic barriers don’t stop people from moving to boom areas like Southern California. Instead, they contribute to a massive pent-up housing demand, a demand that infill developers like Handel struggle to meet. When national home building companies enter a market to meet this demand, they seek out places where land is cheap and plentiful and where regulations are lax, which leads them to rural areas like Winchester. For one thing, land tends to be cheaper when it’s vacant and remote, which makes it much less risky for builders to embark on new subdivisions.

Not only are these subdivisions much more carbon-intensive than infill projects, since they lock in car commutes for thousands of people who could be walking or taking public transit, they also tend to be located in areas that are more vulnerable to climate disasters. The earliest settlement in Los Angeles concentrated around the Los Angeles River basin, which sits in a flat and fire-free bowl close to the coastline. As developers march east into the desert, they are moving into territory that is drier and more mountainous, with a greater risk of fire and a far lower supply of available water. The same thing has happened in San Francisco as suburban expansion spirals into the hilly North Bay and out into the dry Central Valley, and in Houston, where developers have sprawled out into a flood-prone prairie.

“All the easy lands have been identified and developed,” said John Hildebrand, director of planning for Riverside County. “So now we have to encroach farther out into the areas that historically may not have been 100 percent appropriate for development, but we can make them appropriate through mitigation and site design and other things to ensure that there’s health and safety as a primary consideration.”

Some people move to risky areas by choice, but other people don’t have any other option, says Hildebrand. They move to the far exurbs of a city like Los Angeles because everything else is out of their reach.

“You’re a first-time homeowner, you can’t afford a 1,500-square foot house in Orange County,” said Hildebrand. “The cost of housing is pushing people to locate their families out farther and farther where it’s more affordable, and that drives development out here because the land values aren’t as high yet. But over time, those land values start increasing proportionally to where people are coming from, so that continues to drive out development farther.”

This development is made even more attractive by implicit subsidies. In California, Cal Fire and the federal government have covered the cost of wildfire suppression, which means small communities don’t have to pay for their own protection from fires. This amounts to a $726 million annual subsidy for homes in the most vulnerable parts of California. In waterfront areas like Florida, homeowners have benefited from subsidized federal flood insurance premiums that obscure the true cost of a home’s risk.

As the authors of a 2021 paper on housing development in fire zones argue, this kind of exurban development is only affordable in the short term. The new subdivisions along Domenigoni Parkway may give hundreds of families a place to live, but they also ensure future costs by putting homeowners in harm’s way and locking in more carbon emissions.

“It is hard to argue that housing is truly affordable if it comes with the uncertain risk of losing one’s house and personal possessions, risking one’s life, and sky-high insurance premiums,” wrote the authors of that paper, Eric Biber and Monica O’Neill of the University of California, Berkeley.

Just how risky are homes in places like Winchester? It depends on whom you ask. National home builders like Lennar and D.R. Horton have to comply with local construction codes, but they don’t always design their stock for specific climates or hazards, and indeed they’re known for “cookie cutter” homes that look the same in most places. Lennar only expanded the fire evacuation routes in a San Diego development last year after neighbors sued, and D.R. Horton is facing a class-action lawsuit in Louisiana over claims that its standard-issue homes can’t withstand the Gulf Coast heat and humidity. Some of the subdivision sidewalks in the developments around Winchester have the same fences and sidewalk mulch that have allowed previous blazes in other parts of California to spread from home to home in mere seconds.

Even so, many developers have argued that it’s not impossible to build developments that can survive big disasters, and some have even tried to do it. Susan Dell’Osso, the mastermind behind the massive River Islands development in Lathrop, California, is building a 15,000-home subdivision in a flood-prone section of the Central Valley by elevating almost the entire project on the crown of a 300-foot-wide “super levee” that rises away from the nearby San Joaquin River. In addition to this levee, there are other small levees and drainage ponds throughout the development.

“We didn’t want to just do the standard, because we didn’t trust the standard,” Dell’Osso said. “Could we have done it less expensively? Maybe.”

But others disagree. Peter Broderick, an environmental attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity, argues that any wildland-urban interface construction is unacceptable, since the mere presence of human beings in a natural environment leads to more fires igniting. With more frequent wildfires, the grassland ecology of these areas starts to change, allowing for the rise of plants that are even more flammable.

“When you bring a bunch of new people into a wildfire-prone area, the risk of new ignitions just goes through the roof,” Broderick said. “It’s always going to be risky, and no developer can tell you or should tell you that a home can be built fireproof, because that’s just not the case.”

Jay Calderon / The Desert Sun

On paper, the massive Valencia development in the foothills of Santa Clarita sounds like any other Southern California suburb. It occupies a stretch of former ranchland in a mountainous region north of Los Angeles, surrounded on all sides by flammable hills and mere feet from the site of the 2017 Rye Fire, which burned more than 6,000 acres. When finished, it will contain more than 21,000 homes, and all the major home builders are getting in on the action, from Lennar to KB Homes.

But Valencia doesn’t resemble other big developments such as Lennar’s Prairie View. Instead of sprawling out across thousands of acres, the project consists of five dense “villages,” with tight clusters of housing on walkable streets, denser than many neighborhoods in Los Angeles. The same home builders that have laid out thousands of identical single-family homes in other parts of Southern California have built apartment buildings and townhomes here, with solar panels and electric vehicle charging stations. The development borders a designated conservation area for a rare species of spineflower.

This unique project is the result of a long legal battle between the developer, FivePoint Communities LLC, and several environmental organizations including the Center for Biological Diversity. The environmental organizations fought the project in court for over a decade, arguing that it would lead to heavy traffic, worsen climate change, and expose residents to future disaster risk. As FivePoint fought the lawsuits, it also tweaked its development plans to make the project greener and shrink its footprint. In 2017, the company settled with environmental groups, promising to offset Valencia’s carbon emissions and commit around $25 million to conservation.

Over the past decade, as developers have marched into flood and fire zones, environmentalists and neighbors have turned to litigation as a tool to stop or slow down new construction. In the absence of new legislation to spur infill construction or restrict suburban expansion, opponents have had little choice but to fight new suburban projects on an individual basis. In California, many of these lawsuits cite the California Environmental Quality Act, the same law that NIMBYs have used to stop infill construction.

This has been a partial success. Even as builders like Lennar have developed dozens of small subdivisions in cities like Winchester without facing many challenges, organizations like the Center for Biological Diversity have succeeded in using CEQA to slow down or stop much larger projects. The most prominent example of this litigation is Tejon Ranch, a 276,000-acre planned community about 30 miles north of Valencia that was held up in litigation and permitting for two decades before being struck down by a judge last year. California’s Attorney General Rob Bonta also has started to litigate along the same lines, derailing multiple development projects on the grounds that they are too vulnerable to wildfire.

If local governments don’t clamp down on risky development or tax it at higher rates, other forces can slow down the march of sprawl. The federal government could increase subsidies for flood and fire resilience through agencies such as FEMA and the Department of the Interior, paying homeowners and landowners to clear trees around their property or elevate their homes above flood stage. Insurance companies have already started to charge higher premiums for homes in the wildland-urban interface that aren’t built with fire-resilient materials, and lenders could start doing the same. In California, several large insurance companies have stopped offering fire coverage in the state after mounting losses.

But experts say fighting risky development isn’t a true solution to the intertwined housing crises that California faces. If developers have a hard time building projects like Tejon Ranch, it doesn’t necessarily follow that they’ll go back to downtown Los Angeles and build infill. They might just not build anything in Southern California at all, which would further drive up housing prices as a growing population competes for a stagnant supply.

Los Angeles County ran into this problem in 2021 when it tried to limit construction in risky areas. The county undertook a sweeping review of zoning and climate risk in the unincorporated parts of its jurisdiction, hoping to figure out how it could meet its state-mandated housing allocation of 90,000 units without building any homes in flood zones, fire zones, or water-stressed areas. They soon concluded that it wasn’t possible.

“We went through a massive analysis of every single parcel in the unincorporated areas, and we don’t have enough vacant sites in the county that are not in hazard areas,” said Amy Bodek, the county’s director of regional planning. When Bodek and her team found just 30,000 parcels that were both safe and vacant, they moved on to targeting under-utilized areas, including commercial corridors that had fallen on hard times, and worked to loosen zoning where they could. But wherever they went, local politicians and neighbors tried to turn them away, telling them to locate their new density somewhere else.

As Bodek sees it, Los Angeles can’t solve its housing problem without legislation to loosen zoning restrictions and make it easier to build infill. After decades of inaction on these issues, the tide may be turning toward supply reform — if only because the housing crunch in many cities has become politically untenable. The city of Los Angeles has used a 2016 ballot measure provision to launch a transit-oriented development program that allows developers to build denser buildings near rapid transit lines. But there’s a catch: As transit service has declined across the city, some neighborhoods are no longer eligible for the incentives. Still, officials say that more than 50,000 new homes have been built under the new program already.

“We had a city that was laid out so long ago, and had so much more [housing] capacity based on the infrastructure, but we also had a demand for livable neighborhoods,” said Shana Bonstin, the city’s deputy director of planning, of the transit-oriented development push.

There is also some momentum in California’s state legislature, but progress has been uneven. Lawmakers in 2016 voted to loosen rules that stopped many homeowners from building smaller “accessory dwelling units” on their lots. The next year they passed a law called SB35 that streamlined permitting for multifamily housing, and one analysis found that the law has created at least 18,000 new housing units, most in the Bay Area and Southern California. Meanwhile, other efforts haven’t had as much impact: A much-touted bill that loosened zoning restrictions across the state hasn’t encouraged much new construction.

Despite this legislative momentum, there are still big points of contention between environmentalists and pro-construction interests. When pro-housing groups made a deal with labor unions last year to expand that 2017 permitting bill into California’s restricted coastal areas, environmental groups like the Sierra Club objected. Meanwhile, when housing and climate groups teamed up to support a bill that would have sped up approvals for dense housing in cities and raised the regulatory burden for new development in fire-prone areas, the state association of home builders attacked the bill as a “housing killer.”

It’s far from clear when or to what extent the legislature’s recent supply reforms will alter the status quo of the housing market by making infill easier and more alluring than sprawl development. It will likely take several years before the full effect of this legislation becomes apparent in a city like Los Angeles. For now, the economic balance in California still benefits urban homeowners, developers, and local governments in rural areas, as it does in the rest of the country.

“You could imagine a scenario where more insurers pull out, or the plans get super expensive, or the state creates some sort of disincentive for people to move into those areas,” said Hecht, of Earthjustice. “You could imagine there not being a market for those homes, but I feel really far from that right now.”

It likely will take a combination of investments in infill housing and restrictions on wildland development to tilt the scales away from places like Winchester. For as long as the subdivisions along Domenigoni Parkway are cheaper to build and buy than infill developments in big cities, people will continue to trickle out to these places in search of cheap housing.

This dynamic is apparent in the city of Hemet, which sits just 10 miles east of Winchester along Domenigoni Parkway. One of the city’s newest developments is a cookie-cutter subdivision called McSweeny Farms, advertised as a place “where life is easier” and “reminiscent of [a] time when communities were truly communities.”

Monique Foster and her husband Tremaine moved into McSweeny in late April 2022 with their three boys. The Fosters are both from the San Diego area, and moving northeast to Hemet allowed them to become first-time homebuyers, securing a five-bedroom home for under $500,000. Tremaine kept his job in San Diego, commuting at least 90 minutes each way without traffic, and more on a bad day.

Just five months after the Fosters moved in, a blaze known as the Fairview Fire ignited near Hemet and quickly spread through the dry, chaparral-covered foothills around McSweeny Farms. Bolstered by a severe heat wave, drought conditions, and high winds, the fire spread to consume 30,000 acres, creating a wall of flame behind the development.

Mario Tama / Getty Images

“My husband went on Facebook, and he was like, ‘There’s a fire here,’” Monique Foster said. “I said, ‘Where?,’ and I literally just looked out of the kitchen window and saw the big black cloud of smoke right in front of us.” The family evacuated, first to a nearby hotel in Riverside County and then to San Diego.

The Fosters’ home survived the fire, but Monique said the disaster left her “kind of traumatized.” She knew there would be more fires in the scorched foothills around Hemet, and now she felt like she and her family were sitting ducks, waiting for the next blaze.

“I don’t know if I could do it again . . . If this were to become a recurring thing, if it happened again this year, I don’t think I would want to live in this area,” said Monique. Tremaine feels differently: He’s confident that firefighters can keep future blazes under control, and he really likes McSweeny Farms, especially with all the families on Halloween. Plus, the house was affordable, which was more than you could say for San Diego.

“I’ve mentioned to him that I want to move to San Diego, he knows that,” said Monique. “But at the same time, I’ve told him that I don’t know if we could ever get this in San Diego.”

Editor’s note: Earthjustice is an advertiser with Grist. Advertisers have no role in Grist’s editorial decisions.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Why California’s housing market is destined to go up in flames on Jan 24, 2024.