When you think of charcoal, your olfactory receptors may invoke the aroma of skewers on…

The post 8 Ways Activated Charcoal Can Help You Heal & Detox appeared first on Earth911.

When you think of charcoal, your olfactory receptors may invoke the aroma of skewers on…

The post 8 Ways Activated Charcoal Can Help You Heal & Detox appeared first on Earth911.

Iceland has granted a 2024 whaling license to its one remaining whaling company, Hvalur hf., according to the government, drawing criticism from whale protection advocates.

The company will be allowed to kill 99 fin whales in West Iceland and Greenland and 29 of the gigantic mammals in East Iceland and the Faroe Islands, the fisheries ministry said, as Reuters reported.

“It’s ridiculous that in 2024 we’re talking about target lists for the second-largest animal on Earth, for products that nobody needs,” Patrick Ramage, director of International Fund for Animal Welfare, told Reuters.

In Iceland, the whaling season is from the middle of June to late September. Most of the whale meat is sold to Japan.

Fin whales are listed as a “vulnerable” species on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)’s Red List of Threatened Species.

Other than humans, fin whales’ only known natural predator are killer whales, the International Whaling Commission said.

Animal rights groups called the announcement “deeply disappointing,” reported The Guardian.

After Japan, Iceland is the second nation to allow the continuation of fin whaling this year.

During the mid-1900s, the whaling industry killed almost 725,000 fin whales in the Southern Hemisphere, NOAA Fisheries said. Though their numbers have improved and are said to be increasing since hunting bans were implemented by many countries during the 1970s, they are nowhere near what they once were.

Other threats to fin whales include vessel strikes, climate change, fishing gear entanglement, noise pollution and lack of prey from overfishing.

A recent report by the food and veterinary authority of Iceland, Mast, said no significant improvement had been made to the animal welfare status of whale hunts last year compared with 2022, despite new regulations, The Guardian reported.

“It’s hard to fathom how and why this green light to kill 128 fin whales is being given,” Ramage said. “There is clearly no way to kill a whale at sea without inflicting unthinkable cruelty.”

The Mast report found that some whales who had been harpooned did not die for two hours. The report questioned if the hunting of large whales would ever be able to meet animal welfare standards.

“It is unbelievable and deeply disappointing that the Icelandic government has granted [this], defying extensive scientific and economic evidence against such actions,” said Luke McMillan, an anti-whaling activist with Whale and Dolphin Conservation, as reported by The Guardian.

On June 20 of last year, Iceland instituted a two-month suspension on whaling after a government-commissioned inquiry found that the hunting methods being used did not meet animal welfare laws, AFP reported.

In October, Hvalur said 24 whales had been killed during the shortened three-week whaling season.

Whether Bjarkey Olsen Gunnarsdottir, Iceland’s food, fisheries and agriculture minister, would grant a whale hunting license for this year’s season had been unclear.

“It is devastatingly disappointing that Minister Gunnarsdottir has set aside unequivocal scientific evidence demonstrating the brutality and cruelty of commercial whale killing and allowed whales to be killed for another year,” Adam Peyman, wildlife programs director for Humane Society International, told AFP.

“Whales already face myriad threats in the oceans from pollution, climate change, entanglement in fish nets and ship strikes, and fin whale victims of Iceland’s whaling fleet are considered globally vulnerable to extinction,” added Peyman.

The post Iceland Grants License to Kill Vulnerable Fin Whales appeared first on EcoWatch.

The United States Supreme Court has asked the Biden administration to weigh in on oil companies’ efforts to avoid a lawsuit brought by Honolulu. The suit alleges the companies misled the public regarding the contribution of their fossil fuel emissions to climate change and could potentially cost them billions.

The request by the Supreme Court will delay the justices’ decision on whether to hear an appeal by the fossil fuel companies after Hawaii’s highest court ruled the litigation could go to trial.

“Big oil companies are fighting desperately to avoid trial in lawsuits like Honolulu’s, which would expose the evidence of the fossil fuel industry’s climate lies for the entire world to see,” said Richard Wiles, Center for Climate Integrity president, as reported by Reuters.

Documents revealed months ago confirmed that oil companies knew about the impacts of fossil fuels on atmospheric carbon dioxide levels and the environment as early as 1954.

Defendants in the lawsuit include Sunoco, BP, Exxon Mobil, ConocoPhillips, Chevron, Shell, Marathon Petroleum and BHP Group.

The legal position of the Biden administration will be filed by the Justice Department’s solicitor general.

The original lawsuit — filed four years ago by the county and city of Honolulu, along with the city’s water supply board — said the oil majors’ misleading statements regarding the impact of their products opened the door for infrastructure and property damage brought about by human-induced climate change.

The Supreme Court’s order comes after conservative supporters of the companies published a host of advertisements and op-eds, The Guardian reported.

“I have never, ever seen this kind of overt political campaign to influence the court like this,” professor Patrick Parenteau, Vermont Law School senior climate policy fellow, expressed last week to The Guardian.

Climate litigation advocates have said the solicitor general should reject the petition and affirm the earlier decision of Hawaii’s supreme court.

Honolulu is one of many cities and states to have brought legal action against oil companies for concealing the hazards of their products.

The fossil fuel companies insisted federal law should govern the problem of greenhouse gas emissions.

“[T]he Hawaii Supreme Court’s decision flatly contradicts U.S. Supreme Court precedent and federal circuit court decisions, including the Second Circuit which held in dismissing New York City’s similar lawsuit, ‘such a sprawling case is simply beyond the limits of state law.’ These meritless state and local lawsuits violate the federal constitution and interfere with federal energy policy,” Chevron’s lawyer Ted Boutrous said in a statement, as reported by The Hill.

However, plaintiffs Honolulu and its water supply board said the suit is “not seeking to solve climate change or regulate emissions,” but trying to get big oil to “stop lying and pay their fair share of the damages they knowingly caused,” said Alyssa Johl, vice president and general counsel at the Center for Climate Integrity, as The Guardian reported.

The post Can Hawaii Sue Big Oil for Climate Damages? The Supreme Court Wants to Know What the Biden Admin Thinks First appeared first on EcoWatch.

Napa Valley, a famous wine region in northern California, is facing pollution risks from a local landfill.

The Clover Flat Landfill, which has been operating since the 1960s, is located near two streams that flow into the Napa River. According to a news report by The Guardian, the landfill may be contributing to pollution runoff into the nearby waterways.

The Napa River is an important source of water for local agriculture, including vineyards, as well as for recreation.

“The Napa valley is amongst the most high-value agricultural land in the country,” Geoff Ellsworth, the former mayor of St. Helena, a city in Napa County, and a former employee at the landfill, told The Guardian. “If there’s a contamination issue, the economic ripples are significant.”

Emails and reports from former employees and regulators have raised concerns over contamination from the landfill and waste company Upper Valley Disposal Services (UVDS), both of which were once owned by the Pestoni family, according to The Guardian.

As Waste Dive reported in 2022, the landfill and waste disposal service companies were acquired by Texas-based Waste Connections.

Christina Pestoni, the former chief operating officer for Upper Valley Disposal & Recycling and current director of government affairs for Waste Connections, previously shared a statement contradicting the claims made against the landfill and the waste disposal company, asserting that the companies complied with regulations and operated at the “highest environmental standards.” The statement specified that no waste from the Clover Flat Landfill reached or impacted the Napa River.

In December 2023, a group of 23 employees and former employees of the landfill and UVDS filed a complaint to the California Environmental Protection Agency over “impacts from concerning and unlawful environmental practices at UVDS/CFL” with complaints about treatment of Latino workers, threats of retaliation, exposure to untreated garbage wastewater, and ghost piping — which was described in the filed complaint as unmapped piping to divert wastewater and leachate into public waterways.

The complaint also raised concerns over per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) that were found in samples from the landfill’s leachate and groundwater and waste and compost fires that have broken out at the landfill, according to documents obtained by The New Lede, a reporting initiative from Environmental Working Group (EWG).

“Both UVDS and [CFL] have no business being in the grape-growing areas or at the top of the watershed of Napa county,” Frank Leeds, operator of an organic vineyard near UVDS, told The Guardian. “There are homes and vineyards all around that are affected by them.”

Eileen White, executive officer of the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board, told The Guardian that the potential environmental impacts liked to the landfill and UVDS are under investigation.

The post Landfill Pollution Could Threaten Water, Wine in Napa Valley appeared first on EcoWatch.

Since the 1980s, the 85-mile stretch of the Mississippi River that connects New Orleans and Baton Rouge, Louisiana, has been known as “Cancer Alley.” The name stems from the fact that the area’s residents have a 95 percent greater chance of developing cancer than the average American. A big reason for this is the concentration of industrial facilities along the corridor — particularly petrochemical manufacturing plants, many of which emit ethylene oxide, an extremely potent toxin that is considered a carcinogen by the Environmental Protection Agency and has been linked to breast and lung cancers.

But even though the general risks of living in the region have been clear for decades, the exact dangers are still coming into focus — and the latest data show that the EPA’s modeling has dramatically underestimated the levels of ethylene oxide in southeastern Louisiana. On average, according to a new study published on Tuesday, ethylene oxide levels in the heart of Cancer Alley are more than double the threshold above which the EPA considers cancer risk to be unacceptable.

To gather the new data, researchers from Johns Hopkins University drove highly sensitive air monitors along a planned route where a concentration of industrial facilities known to emit ethylene oxide are situated. The monitors detected levels that were as many as 10 times higher than EPA thresholds, and the researchers were able to detect plumes of the toxin spewing from the facilities from as many as seven miles away. The resulting measurements were significantly higher than the EPA and state environmental agency’s modeled emissions values for the area.

“From over two decades of doing these measurements, we’ve always found that the measured concentrations of pretty much every pollutant is higher than what we expect,” said Peter DeCarlo, an associate professor at Johns Hopkins University and an author of the study. “In the case of ethylene oxide, this is particularly important because of the health risks associated with it at such low levels.”

There is no safe level of ethylene oxide exposure. The EPA calculates exposure thresholds for various chemicals by assessing the level at which it causes an increased incidence of cancer. For ethylene oxide, the EPA has determined that breathing in nearly 11 parts per trillion of the chemical for a lifetime can result in one additional case of cancer per 10,000 people. The higher the concentration, the higher the risk of cancer.

DeCarlo and his team found that, in three quarters of the regions where they collected data, ethylene oxide levels were above the 11 parts per trillion threshold. On average, the level was roughly 31 parts per trillion. In some extreme cases, they observed area averages above 109 parts per trillion. The findings were published in the peer-reviewed academic journal Environmental Science & Technology. The study was funded in part by Bloomberg Philanthropies, which launched a campaign in 2022 to block the construction and expansion of new petrochemical facilities.

“We definitely saw parts per billion levels at the fence line of some of these facilities, which means people inside the fence line — workers, for example — are getting exposed to much, much higher concentrations over the course of their day,” DeCarlo said.

Ethylene oxide is emitted from petrochemical manufacturing and plants that sterilize medical equipment. Earlier this year, the EPA finalized rules for ethylene oxide emissions from both types of facilities. The rule that applies to the manufacturing facilities in Louisiana requires companies to install monitors and report data to the EPA and state environmental agency. If the monitors record concentrations above a certain “action level,” companies will be required to make repairs. The rule is expected to reduce emissions of ethylene oxide and chloroprene, another toxic chemical, by 80 percent. Companies have two years to comply.

Heather McTeer Toney, who heads the campaign against petrochemical facilities at Bloomberg Philanthropies, told Grist in an email that the new measurements provide a baseline understanding as the EPA’s new regulations take effect. “The EPA’s new rule was necessary but should only be the start of how we begin to make things right here,” she said. “I’m hopeful to see levels go down, but the data suggest we have a long way to go.”

Tracey Woodruff, a professor studying the impact of chemicals on health at the University of California in San Francisco, said that the study “affirms that EPA is doing the right thing to regulate” ethylene oxide and that the agency “needs to improve their modeling data.” The levels identified by the researchers are 9 times higher than those estimated by the EPA’s models.

For residents in the area, the study’s findings confirm their lived experience. Sharon Lavigne, the founder of Rise St. James, a community organization battling the expansion of the petrochemical industry in St. James Parish, told Grist that the study “is a step in the right direction” and helps the community get a deeper understanding of what they’re being exposed to. But ultimately, without accountability and follow-through, monitoring data will do little to help her family and neighbors.

“These monitors are good, but in the meantime, people are dying,” she said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Real-time data show the air in Louisiana’s ‘Cancer Alley’ is even worse than expected on Jun 11, 2024.

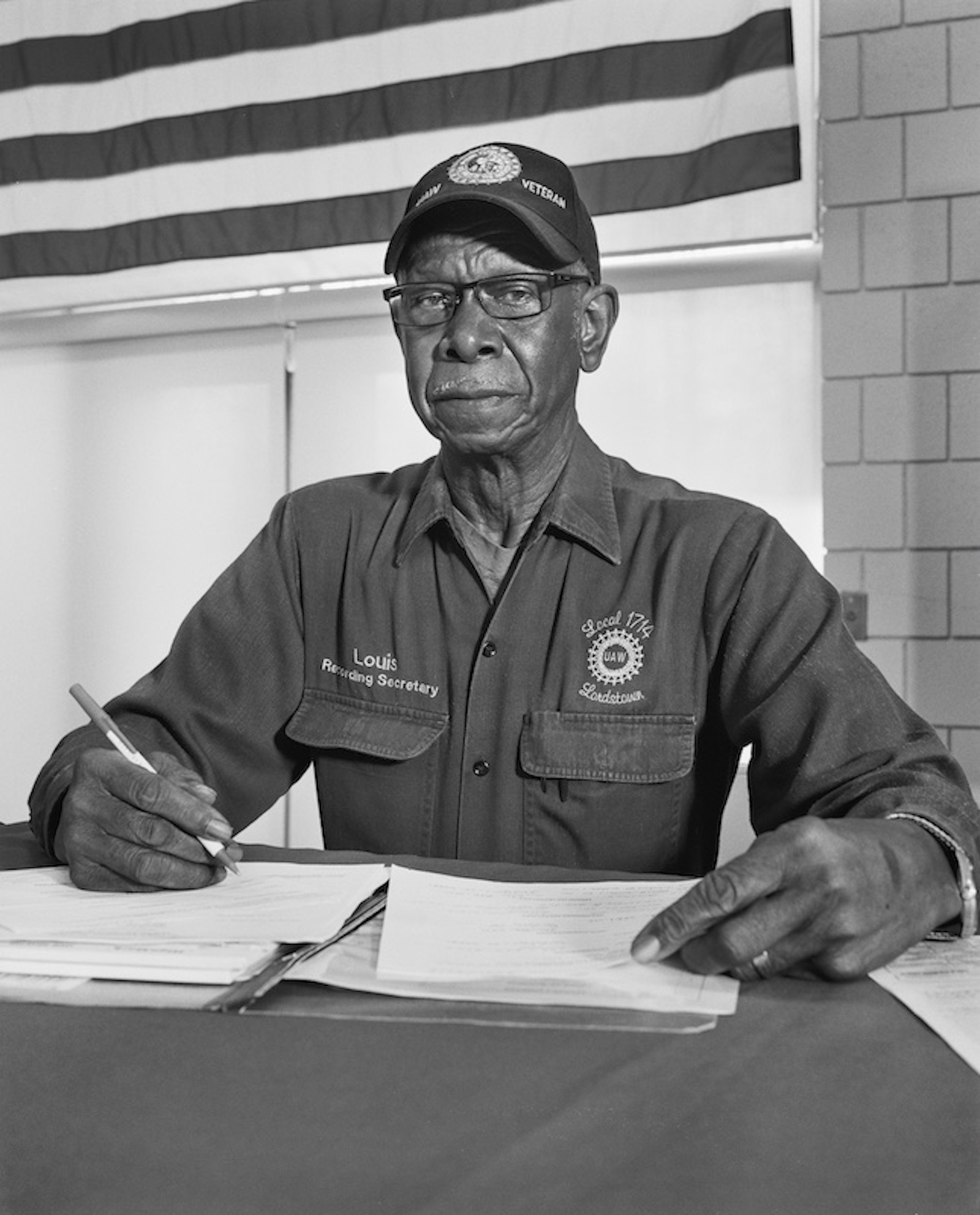

In the winter of 2010, the photographer LaToya Ruby Frazier strapped knee pads over her leggings and pulled on a pair of Levi’s blue jeans. The denim brand had just opened a popup shop on Wooster Street in lower Manhattan to promote a new clothing line designed around the motif of the “urban pioneer.” For the site of its ad campaign, the company chose Braddock, Pennsylvania, aestheticizing the town’s post-industrial landscape in a series of images plastered across magazine pages and New York billboards, and making it appear as a place in motion with ample economic horizons for any working American. “Go Forth,” one ad instructed the viewer over a black and white image of a horse flanked by two denim-clad supermodels. It couldn’t be further from the truth.

Wearing combat boots, a cap, and thick industrial gloves, Frazier, who was born and raised in Braddock, crouched on the sidewalk outside the Manhattan store and began dragging her lower body back and forth over the pavement, first her thighs, then her knees. The moves were choreographed, taken from footage of steel industry workers on the job, and meant to create a dissonance between Levi’s glossy campaign ads and the reality of life in a mill town after a long period of decline. Frazier’s repeated motions made a rough, scratching sound, and the jeans she’d worn began to fray. By the end of the hour, they were in tatters, hanging from her legs.

The short film documenting the performance, LaToya Ruby Frazier Takes on Levi’s, shot by the visual artist Liz Magic Laser, is currently on display at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, part of the exhibit “Monuments of Solidarity,” which showcases more than two decades of Frazier’s work. Themes of deindustrialization, environmental injustice, and unequal health care access are present throughout the photographs on view. From Braddock to Flint, Michigan, during the lead drinking water crisis to Lordstown, Ohio, in the aftermath of the General Motors layoffs, the artist captures communities facing economic declines, not as a single catastrophic event, but as a process initiated by the country’s power brokers and borne by ordinary working-class people. In many towns, what’s primarily left from the industrial past is the pollution, which continues to accumulate in the soil and the water, making people sick even as the hospitals shutter from disinvestment.

What is the purpose of this documentation? Frazier has said that she feels called “to stand in the gap between the working and creative classes,” to use photo-making as a means of resisting “historical erasure and historical amnesia,” symptoms of an economic and political system that discards communities whose labor it no longer deems valuable. She does this by not only taking pictures of working-class people, but also by treating her subjects as “collaborators” and displaying their testimonies alongside their portraits. Some of Frazier’s portraits may look like so much documentary work you’ve seen, but she’s not interested in photography as an isolated or objective act. No art for art’s sake; she invites communities to see themselves in a different way — as historical subjects, as agents in a broader struggle — a step toward believing that they are not powerless.

That the awareness of a person’s agency can alter their lived experience is not theoretical. For half a decade, I’ve reported on communities reckoning with legacy pollution and unbridled industrial expansion, and along the way, I’ve found that a deep sense of the past can have a galvanizing effect. To recognize oneself as belonging to a wider context or system is to also imagine a world beyond its daily injustices, one worth fighting for: What if the chemical company built someplace else? What if the district had the resources to offer its children a future?

I saw this firsthand in my home state, Louisiana, where a maze of petrochemical infrastructure clings to the banks of the lower Mississippi River, dumping cancer-causing chemicals into the air and water of predominantly Black towns, some of which were founded by formerly enslaved people more than a century ago. The people of “Cancer Alley” describe the plants as only the most recent installment in a long arc of racial injustice. Plantations once stood on the mammoth tracts of land where companies like Exxon Mobil, Occidental Petroleum, and BASF erected smoke stacks and ethylene crackers. By telling a different story about their communities, and placing themselves at the center of it, local advocates have had some success in challenging proposed industrial projects in court, arguing that building new facilities over the graves of their enslaved ancestors amounts to a violation of their civil rights and the desecration of historic sites.

Before Frazier could open anyone else’s eyes, she started at home. She was 16 when she first picked up a camera and began photographing herself and her family. In an article timed with the opening of “Monuments of Solidarity,” Frazier describes how she once felt a simple, but no less deeply felt, connection to Braddock as the place where she was born and raised. Witnessing its landscape through her camera’s viewfinder changed that relationship: “My spiritual bondage to Braddock was broken the instant light exposed my film’s silver halide crystals as I created “United States Steel Mon Valley Works Edgar Thomson Plant” (2013), hovering over the city with a bird’s-eye view,” she wrote. “Permeating the 21st century postindustrial landscape were the vestiges of imperial war, patriarchy, and the death and destruction of nature.”

“Monuments of Solidarity” opens with these early works, which are part of her collection “The Notion of Family” (2001-2014). Her primary subjects are herself and the matriarchs that raised her, her mother and grandmother. “I was combating stereotypes of someone like my mother and I,” who are often portrayed as “poor, worthless, or on welfare,” she explained in a 2012 documentary about her work. “We find a way to deal with these types of problems on our own through photographing each other.”

Frazier shot the images on black-and-white film using only the available light. The effect is a sense of intimacy, an impression that the women were asked to look up in the middle of what they were doing or feeling. There is her mother, working the bar at a local restaurant, and again, leaning over the sink with her chest exposed, a jagged scar across her breast, the mark of a recent surgery. In Frazier’s emergent story of herself, the town plays a role, too. Images of Braddock’s abandoned buildings, crisscrossing railroad tracks, and faded billboards are interspersed among the portraits. In one such photo, a mural on the side of a building reads: “JESUS SAID! YOU MUST BE BORN AGAIN! OF WATER & SPIRIT.” Amid images of a run-down Braddock, this one serves a dual function, alluding to local officials’ failed attempts at revitalization and affirming that any rebuilding would have to come from the people themselves, the true witnesses of their own experience.

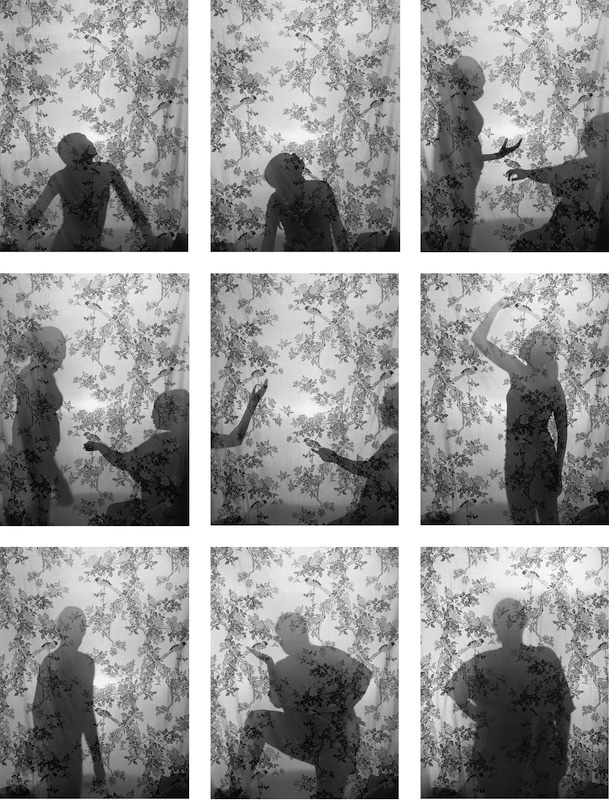

As a storyteller, Frazier doesn’t confine herself to one frame, and frequently uses multiple images to draw connections and offer more complete views of how she sees things. In this mode, Frazier recontextualizes the industrial plant as not just a place to work; she situates it within a broader experience of life. What happens in the plants follows workers into their homes. They suffer the health effects of prolonged chemical exposure. They endure the impacts of job loss.

In one two-panel work, an image of her mother on a hospital bed is placed beside a photo of a demolition site. The slant of her mother’s body and the rope of wires connected to her skull rhyme with the tangle of rebar and concrete of the crumbling building. A nine-panel series shows Frazier and her mother posing behind a patterned cloth, just their shadows visible. The names of the industrial chemicals in Braddock’s air adorn the wall around the frame: benzene, toluene, chloroform. “Your environment impacts your body, and it shapes how you perceive yourself in the world,” the photographer said in the documentary about her work. And in the triptych “John Frazier, LaToya Ruby Frazier, and Andrew Carnegie” (2010), a photo of the artist as a child is set between a historical plaque about John Frazier, a fur trader and frontiersman who aided George Washington in the French and Indian War, and Andrew Carnegie, the industrialist and philanthropist who built Braddock’s first steel factory. With this work, Frazier wrote, she is posing a question: “Weighed against the two colossal Scotsmen that dominate Braddock’s history, what is the value of a Black girl’s life?”

It’s well worth interpreting Frazier’s subsequent work as her own answer to that question. In 2016, she spent five months living in Flint, Michigan, photographing residents as they lived through the worst days of the city’s lead drinking water crisis. Like Braddock, Flint experienced a prolonged deindustrialization crisis, with General Motors slashing its local workforce from 80,000 in 1978 to under 8,000 by 2010. Over the same period, the city’s population nearly halved. The public health emergency started in 2014 after the cash-strapped local government elected to divert the city’s water source from the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department to the Flint River, causing levels of bacteria and lead in the city’s water supply to spike. While in Flint, Frazier met Shea Cobb, a local poet and activist, and her daughter Zion, whom she would come to document across the three-part series, “Flint Is Family.” Like Frazier’s mother, who helped stage and shoot many of the portraits in Braddock, Cobb became someone who had a say in the work, an artist in her own right.

Over the years, Frazier followed Cobb and her daughter as they moved in with Cobb’s father in Newton, Mississippi, where they sought refuge from the lead crisis, lived closer to nature, and learned to care for horses. She also photographed the family as they moved back to Flint after Zion experienced discrimination in her Mississippi school. The photographs from Newton and the family’s return to Flint depart from the black and white of Frazier’s earlier photography, creating a sense of vibrancy and forward momentum in spite of the hardships they faced. In perhaps the most striking photograph of the series, Zion poses on a horse, one hand on her hip, flanked by her mother and grandfather, also on horses. The three generations stare down the camera defiantly.

“We laugh sometimes to throw off the frustration,” Cobb said in a text accompanying one of her portraits in the exhibit. “We brush our teeth, we laugh.”

In the end, Frazier’s work engages an enduring, if cliche question: Can art change things? On one of her trips to Flint, Frazier learned about the invention of an atmospheric water generator that could supply clean water to the most neglected areas of the city. When local officials indicated that they weren’t interested in the technology, Frazier decided to use funds from an exhibit of her early photos of Flint to pay for the machine’s transportation.

The process is incremental, a slow revealing of places and people once unseen, cast in new light. Can journalism change things?

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline What is LaToya Ruby Frazier trying to show us? on Jun 11, 2024.

Each year, nearly 1.3 million households across the country have their electricity shut off because they cannot pay their bill. Beyond risking the health, or even lives, of those who need that energy to power medical devices and inconveniencing people in myriad ways, losing power poses a grave threat during a heat wave or cold snap.

Such disruptions tend to disproportionately impact Black and Hispanic families, a point underscored by a recent study that found customers of Minnesota’s largest electricity utility who live in communities of color were more than three times as likely to experience a shutoff than those in predominantly white neighborhoods. The finding, by University of Minnesota researchers, held even when accounting for income, poverty level, and homeownership.

Energy policy researchers say they consistently see similar racial disparities nationwide, but a lack of empirical data to illustrate the problem is hindering efforts to address the problem. Only 30 states require utilities to report disconnections, and of those, only a handful provide data revealing where they happen. As climate change brings hotter temperatures, more frequent cold snaps, and other extremes in weather, energy analysts and advocates for disadvantaged communities say understanding these disparities and providing equitable access to reliable power will become ever more important.

“The energy system as it is currently designed is failing to adequately serve all customers,” said Shelby Green, a researcher with the nonprofit Energy and Policy Institute. “Economically disadvantaged and minority people’s lives will be the ones most at threat.”

The research in Minnesota, led by Bhavin Pradhan and Gabriel Chan, found that households of color served by Xcel Energy experienced disproportionately more shutoffs and more frequent outages. Between 2020 and 2022, neighborhoods with the highest concentration of people of color were 47 percent more likely than other areas to lose power for more than half a day.

Pradhan told Grist he was surprised to find that those racial differences held even over a period of several years. “It wasn’t just one year where there was a spike, but consistently over time,” he said. The team analyzed data for groups of a few hundred households from 2017 to 2022 — a level of spatial detail that allowed them to isolate the effect of race at a neighborhood level. Xcel Energy has noted that its own grid equity analysis found similar racial disparities in shutoffs and outages. But the utility highlighted the age of a home as an equally significant factor for extended outages, and largely attributed cutoffs to a customer’s income. In a submission to the public utilities commission, the company noted that “disconnections are correlated with poverty, and — for a variety of deeply entrenched economic and social reasons that are not driven by the energy system — poverty is correlated with race.” It added that the utility offers programs to help customers cover their bills.

Erica McConnell, staff attorney at the Environmental Law and Policy Center, countered that the utility’s own disconnection data proves those efforts are insufficient. Xcel Energy is currently updating a five-year plan outlining future grid investments, a process McConnell says provides an opportunity for the utility and regulators to invest in communities disproportionately impacted by disconnections and outages. The Center and other organizations have also called on the state Public Utilities Commission to consider reinstating a moratorium on disconnections, introduced at the height of the pandemic, until it can determine how best to address these disparities.

One potential measure that could help is expanding community solar, battery storage, and other distributed energy resources. The University of Minnesota study found that the communities bearing an outsized burden of disconnections and outages also have the greatest capacity to host small-scale clean energy projects like rooftop solar — a point McConnell echoed.

“Historically, a lot of communities haven’t had access to those kinds of programs,” she said. In the long term, distributed energy resources that “encourage ownership by the communities and wealth-building could be a valuable way to address the issue” by ensuring residents have access to cheap, reliable power.

Green, the researcher at the Energy and Policy Institute, noted that rather than simply pointing to broader issues, utilities like Xcel Energy should look at how their operations might be perpetuating or amplifying existing inequities.

Minnesota’s study is one of a few that have documented the role race plays in shutoffs. In Illinois, researchers found that from 2018 through 2019, electricity customers in predominantly Black and Hispanic zip codes were four times more likely to be disconnected than other areas, even when accounting for income and other factors. A national survey by researchers at Indiana University reached a similar conclusion: between April 2019 and May 2020, researchers found that Black and Hispanic households were roughly twice as likely to have their power shut off compared to white households.

Those studying energy insecurity aren’t sure exactly what causes so strong a correlation between race and shutoffs. Sanya Carley, a professor and researcher at the University of Pennsylvania’s Kleinman Center for Energy Policy, cites two possible factors. One is energy burden, or the proportion of a household’s income spent on gas and electricity. The other is the age of their housing, since older buildings tend to be less energy efficient. But her team’s research has found that those reasons account for only around 10 percent of the racial disparities found in utility disconnections.

“There is something left unexplained about the energy experiences of Black and Hispanic households that needs to be identified to fully understand the prevalence of energy insecurity in these groups,” the study authors wrote. Green suggested another factor could be implicit bias in utility operations. A customer service representative, for example, could respond less leniently to a customer living in a community of color or low-income area. But overwhelmingly, energy policy experts told Grist that more data is needed to understand the extent of racial inequities and the forces driving them. Carley noted that unless required by law, most utilities don’t voluntarily share data on disconnections. Just six states, including Minnesota, Illinois, and California, require location data on utility shutoffs, typically at the zip code level. In most others that require reporting, utilities often share only the total number of disconnections each year. What’s more, those laws apply only to regulated investor-owned utilities, meaning municipal utilities or co-ops may not share any data at all.

Energy justice advocates have long called for widespread requirements for utilities to report on disconnections and who they impact. Pradhan, the co-author of Minnesota’s study, told Grist that access to such data could enable “more studies and more data-driven decisionmaking” on where and how utilities should invest in improving their grid and electricity service.

More urgently, Carley, Green, and others say consumer protections against disconnections can shield households from the brunt of life-threatening cutoffs. Already, 41 states prevent or limit utilities from disconnecting customers during bouts of extreme cold. But only 20 states, including Minnesota, have restrictions against shut-offs during periods of extreme heat — though that is beginning to change. After a deadly 2021 heat dome across the Pacific Northwest, lawmakers in Washington passed a law last summer preventing utilities from cutting off power to customers on days when a heat-related alert is issued.

“Power and water can be a matter of life and death during a heat wave,” Washington State Representative Sharlett Mena said at the time. “This legislation will ensure that every Washingtonian has the ability to protect themselves against extreme heat.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline A lack of data hampers efforts to fix racial disparities in utility cutoffs on Jun 11, 2024.

If your family is anything like ours, the kitchen is easily the most used room…

The post How To Cook Up a Zero-Waste Kitchen appeared first on Earth911.

Elephants are some of the most intelligent, compassionate and social creatures on Earth, forming tight-knit family groups, social networks and an extended “clan structure,” the members of which not only care for each other, but, as new research shows, call each other by name.

A new study by researchers from Save the Elephants — a conservation and research organization based in Kenya — ElephantVoices and Colorado State University (CSU) has found that when wild African elephants are called by their names, they answer back. They also address one another with name-like calls — a rarity among nonhuman animals.

“Personal names are a universal feature of human language, yet few analogues exist in other species. While dolphins and parrots address conspecifics by imitating the calls of the addressee, human names are not imitations of the sounds typically made by the named individual,” the authors wrote in the study. “Here we present evidence that wild African elephants address one another with individually specific calls, probably without relying on imitation of the receiver.… Moreover, elephants differentially responded to playbacks of calls originally addressed to them relative to calls addressed to a different individual.”

Using machine learning, the research team confirmed that elephants’ calls had a name-like feature that identified the intended recipient, which they had suspected based on earlier observations, a press release from CSU said.

When recorded calls were played back, elephants responded to those addressed to them with response calls or by approaching the speaker. Calls intended for other elephants did not receive as much of a reaction.

“[O]ur data suggest that elephants do not rely on imitation of the receiver’s calls to address one another, which is more similar to the way in which human names work,” said lead author of the study Michael Pardo, who was a postdoctoral researcher for the National Science Foundation at Save the Elephants and CSU during the study, in the press release.

Learning to produce novel sounds is rare among animals, but a necessary feature of identifying individuals by name. A sound that represents an idea without imitating it is called “arbitrary communication” and is seen as a “next-level cognitive skill” that vastly augments the ability to communicate.

“If all we could do was make noises that sounded like what we were talking about, it would vastly limit our ability to communicate,” said co-author of the study George Wittemyer, a CSU professor at the Warner College of Natural Resources, as well as chairperson of Save the Elephants’ scientific board, in the press release.

Wittemyer added that elephants’ use of arbitrary vocal labels means they may also be capable of abstract thinking.

Their complex social systems, similar to those of humans, likely led to the evolution of arbitrary vocal labeling of individuals using abstract sounds, the researchers said.

“It’s probably a case where we have similar pressures, largely from complex social interactions. That’s one of the exciting things about this study, it gives us some insight into possible drivers of why we evolved these abilities,” said Wittemyer.

Elephant calls communicate not just their identity, but their sex, age, emotional state and context of their behavior.

Their vocalizations include low rumbles and trumpeting across a wide spectrum of frequencies, including infrasonic sounds too low for humans to hear. Group movements can be coordinated by using these calls over long distances.

“Our finding that elephants are not simply mimicking the sound associated with the individual they are calling was the most intriguing,” said Kurt Fristrup, a CSU research scientist with the Walter Scott, Jr. College of Engineering, in the press release. “The capacity to utilize arbitrary sonic labels for other individuals suggests that other kinds of labels or descriptors may exist in elephant calls.”

The four-year study included 14 months of fieldwork in Kenya where the team recorded elephant vocalizations while following them in a vehicle. They captured approximately 470 distinct calls from 101 individual callers to 117 receivers in Amboseli National Park and Samburu National Reserve.

The study, “African elephants address one another with individually specific name-like calls,” was published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

Wittemyer noted that elephants are expressive and those who are familiar with them can easily read their reactions. Samples played back resulted in elephants responding positively and “energetically” to recordings of family members and friends calling to them, while calls directed to others did not garner an enthusiastic response or movement toward the caller, indicating they recognized their own names.

The researchers also discovered that, like humans, elephants don’t always use each other’s names in conversation. Addressing an individual by their name was more often seen when adult elephants were talking to calves or addressing others over long distances.

The research team said they would need much more data to be able to distinguish names within calls to determine if elephants give labels to things such as food, water and specific locations.

Elephants are listed as endangered, primarily due to habitat loss and poaching. The researchers said new insights into their communication and cognition as revealed in the study further bolster the case for conserving these magnificent animals.

Pachyderms need a lot of space because of their size. Wittemyer explained that, while humans conversing with elephants is still far off, the ability to communicate with them could enhance their protection.

“It’s tough to live with elephants, when you’re trying to share a landscape and they’re eating crops. I’d like to be able to warn them, ‘Do not come here. You’re going to be killed if you come here,’” said Wittemyer.

The post Elephants Call Each Other by Name, Like Humans Do, Study Finds appeared first on EcoWatch.

The United States Department of Transportation (USDOT) has tightened fuel mileage standards for vehicles in an effort to transform the country’s auto market into one dominated by more climate-friendly electric vehicles.

The new standards set by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) will lower fuel costs by more than $23 billion while reducing pollution, a press release from USDOT said.

“Not only will these new standards save Americans money at the pump every time they fill up, they will also decrease harmful pollution and make America less reliant on foreign oil. These standards will save car owners more than $600 in gasoline costs over the lifetime of their vehicle,” said U.S. Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg in the press release.

The new standards will save nearly 70 billion gallons of gas through 2050 and prevent more than 782.6 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions by mid-century.

“When Congress established the Corporate Average Fuel Economy program in the 1970s, the average vehicle got about 13 miles to the gallon. Under these new standards, the average light-duty vehicle will achieve nearly four times that at 50 miles per gallon,” said Sophie Shulman, NHTSA deputy administrator, in the press release.

The final rule will increase fuel economy by two percent annually for passenger cars with model years 2027 to 2031 and light trucks with model years 2029 to 2031. This will mean that by model year 2031, the average light-duty vehicle will get roughly 50.4 miles per gallon.

The new rules are not as strict as last year’s USDOT draft rules, which would have required that automakers make passenger cars with an average 66.4 miles per gallon and light trucks with a standard 54.4 miles per gallon before 2032, reported The New York Times. The proposal was weakened following lobbying from automakers.

Under the new final rule, van and heavy-duty pickup truck fuel efficiency will go up by 10 percent each year for vehicles with model years 2030 to 2032, while model years 2033 to 2035 will increase by eight percent annually. This will mean an average of roughly 35 miles per gallon fleetwide by model year 2035, resulting in a savings of more than $700 in gasoline costs for van and heavy-duty pickup owners.

“President Biden’s economic and climate agenda has catalyzed an American clean energy and manufacturing boom,” said national climate advisor Ali Zaidi in the press release. “On factory floors across the nation, our autoworkers are making cars and trucks that give American drivers more choices today than ever before. These fuel economy standards, rigorously aligned with our investments and standards across the federal government, deliver on the Biden-Harris Administration’s promise to build on this momentum and continue to spur job creation, and move faster and faster to tackle the climate crisis.”

NHTSA consulted with unions, consumers, environmental advocates, states, automakers and other stakeholders in the process of crafting the final rule.

The new rule sets standards consistent with the direction of Congress regarding the conservation of fuel and promotion of the country’s automotive manufacturing and energy independence, while at the same time giving the automotive industry flexibility on how to reach those goals.

“Though NHTSA does not consider electric and other alternative fuels when setting standards, manufacturers may use all available technologies – including advanced internal combustion engines, hybrid technologies and electric vehicles – for compliance,” the press release said.

The updated fuel economy standards set by NHTSA complement similar vehicle fleet emissions standards set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). NHTSA worked with the EPA to improve its standards while minimizing the costs of compliance, consistent with relevant statutory factors.

“These new fuel economy standards will save our nation billions of dollars, help reduce our dependence on fossil fuels, and make our air cleaner for everyone. Americans will enjoy the benefits of this rule for decades to come,” Shulman said.

The post Biden Admin Tightens Vehicle Mileage Standards in Effort to Bolster EVs and Fight Climate Change appeared first on EcoWatch.