To get to the Super Bowl on time, Taylor Swift took a private jet from Tokyo to Los Angeles and then hustled to Las Vegas. The carbon removal company Spiritus estimated that her journey of roughly 5,500 miles produced about 40 tons of carbon dioxide — about what is generated by charging nearly 5 million cell phones. But don’t worry, the company assured her critics: It would take those emissions right back out of the sky.

“Spiritus wants to help Taylor and her Swifties ‘Breathe’ without any CO2 ‘Bad Blood,’” it said in a pun-laden pitch to reporters. “It’s a touchdown for everyone.”

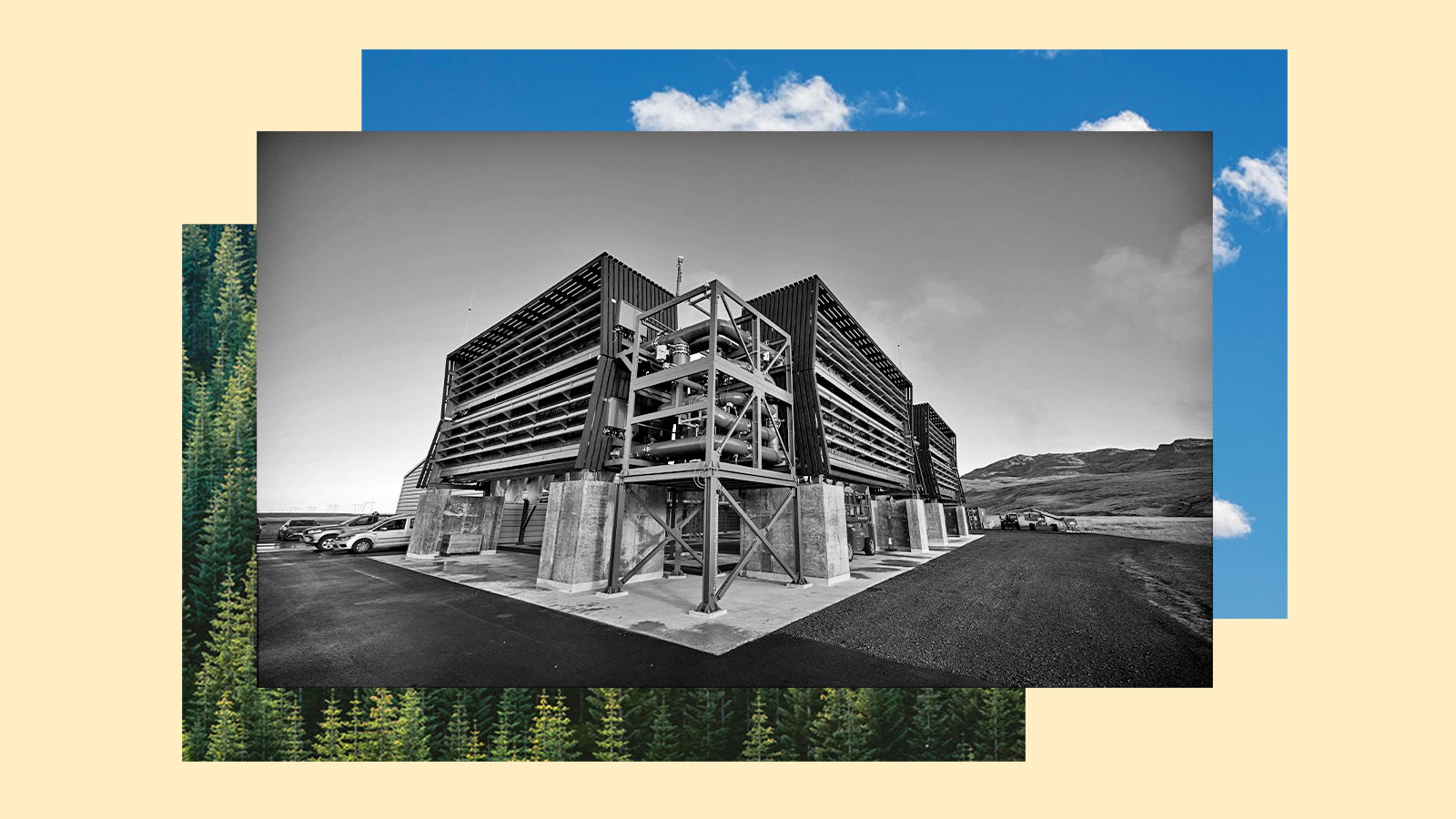

The startup is among dozens, if not hundreds, of businesses trying to permanently remove climate-warming gases from the atmosphere. Its approach involves drawing carbon directly from the air and burying it, but others sink it in the ocean. Last week, Graphyte, a venture backed by Bill Gates, began compacting sawdust and other woody waste that are rich in carbon into bricks that it will bury deep underground.

Spiritus says “sponsoring carbon offsets is a step toward environmental responsibility, not an endorsement of luxury flights” and added that “celebrities are going to take private jets regardless of what Spiritus does.” Even before the company stepped in, Swift reportedly planned to purchase offsets that more than covered her travel. But some climate experts say moves like Spiritus’ illustrate the dangerous direction the rapidly growing carbon dioxide removal, or CDR, industry is headed.

“The worry is that carbon removal will be something we do so that business-as-usual can continue,” said Sara Nawaz, director of research at American University’s Institute for Carbon Removal Law and Policy. “We need a really big conversation reframe.”

The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says carbon removal will be “required” to meet climate targets, and the United States Department of Energy has a goal of bringing the cost down to $100 per ton (a price point Spiritus claims it wants to deliver as well). What concerns Nawaz is the outsize role that private companies are currently playing.

“It’s very market-oriented: doing carbon removals for profit,” Nawaz said. That reliance on the market, she elaborated, won’t necessarily lead to the just, equitable, and scalable outcomes that she hopes CDR can achieve. “We need to take a step back.”

Nawaz co-wrote a report released today titled “Agenda for a Progressive Political Economy of Carbon Removal.” In it, she and her co-authors lay out a vision for carbon removal that shifts away from market-centric approaches to ones that are government-, community-, and worker-led.

“What they suggest is quite radical,” said Lauren Gifford, associate director of the Soil Carbon Solutions Center at Colorado State University who was not involved in the research. She supports the direction the authors advocate, adding, “They actually give us a roadmap on how to get there, and that in itself is progressive.”

Nawaz compared carbon removal’s current trajectory to the bumpy path that carbon offsets has followed. That industry, in which organizations sell credits to offset greenhouse gas emissions, has been plagued by misleading claims and perverse incentives. It has also raised environmental justice concerns where offsets are disproportionately impacting frontline communities and developing nations. For example, Blue Carbon, a company backed by the United Arab Emirates, has been buying enormous swaths of land in Africa to fuel its offsets program.

“We don’t want to do that again with carbon removal,” she said.

Philanthropy is one possible alternative to corporate carbon removal. The report cites a nonprofit organization called Terraset that puts tax-deductible donations toward CDR projects (including Spiritus’). But, Nawaz says, that approach won’t grow quickly or sustainably enough to remove the many gigatons of emissions needed to meaningfully address climate change.

“That’s not a scalable approach,” she said. “We’re going to need so much more money.”

The report argues that communities and governments must play a central role in the industry. Nawaz cites community-driven carbon removal efforts out West, such as the 4 Corners Carbon Coalition, as examples of what might be possible on the local level. Nationally, she points to Germany’s transition away from coal as a way that governments can not only fund but fundamentally drive clean energy policy that puts workers at the fore.

To be sure, the United States is investing in carbon removal. The bipartisan infrastructure law and Inflation Reduction Act included billions of dollars for technology such as regional direct air capture hubs. But the legislation mostly positions the government as a funder or purchaser of carbon removal initiatives rather than a practitioner.

“It’s, frankly, a pretty disappointing way it’s evolving,” said Nawaz, noting, for instance, that Occidental Petroleum is among those receiving federal funding for carbon removal. She would like to see the government take a more hands-on role. “Not just government procurement of carbon removal. But actually government-led research and early-stage implementation of carbon removal.”

Gifford agrees that there are dangers in the industry relying too much on the private sector. “There’s something really scary about putting the climate crisis in the hands of wealthy tech founders,” she said. But companies have also been at the forefront of advancing the field as well. “The climate crisis is one of these things that’s all-hands-on-deck.”

Those in the private sector say their efforts are critical to ensuring that carbon removal technology is developed and deployed as quickly as possible. “Our coalition represents innovators,” said Ben Rubin, the executive director of the Carbon Business Council, a nonprofit trade association representing more than 100 carbon management companies. ”There won’t necessarily be one silver bullet.”

“There’s a long history of public-private partnerships ushering in some of the world’s latest and greatest innovations,” added Dana Jacobs, the chief of staff for the Carbon Removal Alliance, which similarly represents startups in this space. “We think carbon removal won’t be any different.”

Nawaz and her colleagues want to shake that paradigm before it’s too deeply entrenched. The alternative could be continued unjust outcomes for marginalized people and limited progress on luxury emissions, such as Swift’s flight to the Super Bowl.

“The idea is that carbon removal is a public good,” she said. “We shouldn’t have to rely on just the private sector to provide it.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Taylor Swift’s Super Bowl flight shows what’s wrong with carbon removal on Feb 13, 2024.