Nature is a continuous cycle that, when humans break it, ceases to function correctly. Xenophon,…

The post Earth911 Inspiration: Nature Gives More Than You Return appeared first on Earth911.

Nature is a continuous cycle that, when humans break it, ceases to function correctly. Xenophon,…

The post Earth911 Inspiration: Nature Gives More Than You Return appeared first on Earth911.

Tim Robinson is famous for making uncomfortable social situations funny — in a cringe-inducing way. On his Netflix sketch show I Think You Should Leave, he’s played a range of oddball characters: a contestant on a replica of The Bachelor who’s only there for the zip line; a man in a hot dog costume who claims he’s not responsible for crashing the hot dog car through the window of a clothing store; a guy wearing a really weird hat at work. These sketches are, for the most part, an escape from the heavy subjects that keep people up at night.

So it might come as a surprise that Robinson’s next move was a climate change PSA. “I’m sick and tired of scientists telling us mean, bad facts about our world in confusing ways,” Robinson shouts at the camera in a recent sketch. Playing a TV host named Ted Rack, he invites a climate scientist on his show “You Expect Me to Believe That?” for a messaging makeover.

It’s produced by Yellow Dot Studios, a project by Adam McKay (of Don’t Look Up fame) that’s recently been releasing comedic videos to draw attention to a global problem that most people would probably rather not think about. Sometimes the resulting videos are only mildly amusing: In a recent one, Rainn Wilson, Dwight from The Office, presents the case against fossil fuels to the court from Game of Thrones. But for a comedian like Robinson who thrives on a sense of unease, talking about climate change isn’t just a public service; it’s prime material.

In the sketch, the subject of the Queer Eye-style makeover is Henri Drake, a real-life professor of Earth system science at the University of California, Irvine. Ted Rack’s first step is to outfit Drake in a jersey with the number 69. “Let’s focus on making your messaging a little more appealing to someone like me,” Rack says. “Someone who, like, when I hear it, I get a little mad because I don’t understand it.” Robinson is famous for his facial acrobatics, and his expressions grow increasingly perturbed as Drake describes how fossil fuels have warped Earth’s “radiation balance.” By the end, Rack is holding his head in his hands. “I gotta be honest,” he says. “What you’re saying to me makes me want to fight you a little.”

The video struck a chord with the public, racking up 100,000 views on TikTok and almost a quarter million on YouTube. It also resonated with some scientists. “I immediately understood where this is coming from,” said Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles, and the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, after watching the video. “I feel the same pressures, I get the same complaints.” After he gives scientific talks, the most common response he hears is along the lines of “Oh my god, you’re just so depressing.”

The sketch touches on similar themes as Don’t Look Up, McKay’s 2021 film that portrays a distracted, celebrity-obsessed world ignoring scientists’ warnings of an approaching asteroid. Rack, though, wants to help avoid the disaster that ensues when no one pays attention to scientists’ “terrible message,” and he finds ridiculous ways to make climate science relatable. “Here’s what you should say,” he instructs Drake. “‘Your house is about to be part of the ocean … A shark could swim in there and eat a picture of your daddy.’”

As a scientist with a self-described dark sense of humor, Swain enjoyed the sketch. He thought it did a good job satirizing the expectation that scientists, as the bearers of bad news, should be “cheery cheerleaders.” At the same time, though, Swain thinks a lot of climate scientists really could use a communication makeover. “I absolutely agree that a lot of times where the scientists engaged with the wider world are really ineffective,” he said. Jargon scares people off. And even if people stick around for technical discussions of, say, Earth’s radiation balance, they might disengage when the conversation turns to ecological collapse, even though it’s the crux of why the topic matters at all. The story of how humans have made the world hotter and more hostile is a difficult one to hear, especially when accepting it means you might be a tiny part of the problem.

If experts are having trouble talking about climate change, you can bet that the general public does, too. Two-thirds of Americans say climate change is personally important to them, but only about half that number, just over a third, actually talk to their friends and family about it, according to the most recent survey from the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. People might be hesitant to express their thoughts because they mistakenly believe that their opinions are unpopular, or simply because scary things are just hard to talk about.

Weirdly enough, that’s what makes climate change a good subject for a Robinson sketch. A recent profile of the comedian in The New York Times Magazine — which begins with Robinson spooning an absurd amount of hot chiles over his noodles at a restaurant — compares an affinity for spicy food to the appeal of cringe comedy. “In a harsh world, it can be soothing to microdose shots of controlled pain,” wrote Sam Anderson, the author of the profile. “Comforting, to touch the scary parts of life without putting ourselves in real danger. Humor has always served this function; it allows us to express threatening things in safe ways. Cringe comedy is like social chile powder: a way to feel the burn without getting burned.”

Climate scientists, too, could spice up their talking points — if they were given resources to do so. “I think everyone kind of understands why this exists and is funny,” Swain said. “But the reason why that’s the case — why there aren’t engaging, funny climate scientists out there on TV — is nobody is facilitating that in any setting.” The real barrier, Swain says, is that the places where scientists work don’t generally support public communication as part of their job.

Swain is just one of a handful of climate scientists with a very high level of public visibility, appearing all over TV news, articles, YouTube, and social media. He thinks he’s been featured on more podcasts than he’s ever listened to in his life. But he’s concerned that funding for his communications work will soon run out, with nothing to replace it. “I am still working through this myself,” Swain said. “I mean, I don’t know what my employment’s going to be in six months, because I can’t find anybody to really support this on a deeper level.”

Finding a climate scientist who had time to talk about a silly, five-minute video was also a bit of a challenge. Zeke Hausfather, another media favorite, was swamped; Drake, from the video, apologized but said that it was the busiest week of the year; other scientists didn’t respond. The initial email to Swain resulted in an auto-reply advising patience amid his “inbox meltdown.” As a one-man team, Swain wrote, he could only respond to a fraction of the correspondence coming in.

Talking to a journalist about comedy clearly isn’t at the top of the priority list for most scientists. But Swain doesn’t think it’s a waste of time. By now, he’d hoped that climate change would have a bigger role in comedy sketches, bad movies, and trashy TV shows, meeting people where they already are. “Where is the pop culture with climate science? It’s not where I thought it would be at this point,” he said. “But pop culture changes quickly. It responds fast to new things that are injected into the discourse.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Talking about climate change can be awkward. Just ask Tim Robinson. on Feb 16, 2024.

Indigenous nations, farmers, and ranchers throughout the Klamath Basin in the Pacific Northwest reached an agreement on Wednesday to collaborate on ecosystem restoration projects and to improve water supply for agriculture.

The memorandum between the Klamath Tribes, Yurok Tribe, and Klamath Water Users Association, which represents agricultural producers across 17,000 acres in both California and Oregon, serves as a major step in a long-running battle over access to water as the Klamath River dries up and federal officials cut flows to tribes and producers.

Drought in the region has often pitted Indigenous peoples and endangered fish against more than 1,000 farms that rely on the same water for their crops. In 2001, the Bureau of Reclamation shut off irrigation water to farmers in the midst of a drought, prompting protests from farmers and illegal water releases. Two decades later, amid another drought, the agency cut water to farmers to preserve endangered suckerfish, again heightening tensions. ”It’s not safe for Natives to be out in farmland during a drought year,” Joey Gentry, a member of the Klamath Tribes, told Inside Climate News after the 2021 water cuts.

In 2022, tribes won a long-running campaign to convince the federal government to remove four dams that stopped salmon from reaching their spawning grounds, marking a major win for Indigenous communities that rely on the Klamath. Now, Clayton Dumont, chairman of the Klamath Tribes, says the new agreement goes even further.

“We’re nowhere near finished, but this is a really strong beginning,” he said. “Getting adversaries like this together in a room and having to sit through a lot of bitterness to get to a point where we are now, I think it’s not just commendable, it’s pretty miraculous.”

Klamath Tribes were forced to cede 23 million acres in Oregon and California to settlers in exchange for a reservation, but an 1864 treaty gave the tribe the right to hunt and fish on those ceded lands forever. However, fishing hasn’t been consistently possible with drought and conflicting demands for water.

“What’s at stake is our very livelihood, our culture, our identities, our way of life,” Dumont said.

In the next month, tribes and agricultural producers will meet to decide on restoration projects that could be completed within the next two years and supported through existing federal or state programs. After the priorities are decided, officials from the U.S. Department of the Interior will identify both existing funding and new funding sources for the projects. The agency also plans to release more than $72 million to modernize agricultural infrastructure and restore the ecosystem in Klamath Basin.

Officials from the Klamath Water Users Association said in a press release that working together with the tribes will make both parties more effective in obtaining state and federal funding to support the region.

“I am hoping that this MOU will be the first step to bring all the different entities together to work on a solution to the conflicts over water that have hampered this region for decades,” said Tracey Liskey, president of the Klamath Water Users Association Board of Directors. “The water users want fish in our rivers and lakes and water in our irrigation ditches. This way, we all can have a prosperous way of life in the basin.”

Dumont says it helped that the administrations locally, statewide, and federally were all supportive of this agreement. However, he added that there’s no guarantee that the MOU will have any staying power after November.

“If the election goes the wrong way, all of this could dry up really quickly,” Dumont said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline As the Klamath River dries, tribal nations and farmers come to rare agreement on Feb 16, 2024.

Government employees in Bangkok have been ordered to work from home for the next two days in order to avoid a thick layer of noxious smog covering the city.

On Thursday, authorities warned that air pollution levels in Thailand’s capital and neighboring provinces had reached unhealthy levels, reported Reuters. Non-government employees have been urged to stay home as well.

Governor of Bangkok Chadchart Sittipunt said the mandatory work-from-home days would affect more than 60,000 people on Thursday and Friday, according to AFP.

Authorities asked for employers’ cooperation in helping workers avoid the toxic pollution until it improves on Friday.

“I would like to ask for cooperation from the [Bangkok Metropolitan Administration] network of about 151 companies and organizations, both government offices and the private sector,” Sittipunt said in a statement, as AFP reported.

On Thursday morning, Bangkok was ranked in the top 10 most polluted cities globally by Swiss air quality tracker IQAir.

According to the IQAir website, levels of PM2.5 particles — considered the most dangerous and small enough to enter the bloodstream — were 15 times higher than the recommended guidelines set by the World Health Organization.

Bangkok’s air quality issues come from industrial pollution, agricultural burning and busy traffic.

Prime Minister of Thailand Srettha Thavisin said crop burning was the biggest factor in the jump in pollution, adding that about 25 percent of it came from vehicles, reported Reuters.

Last month, the Department of Pollution Control said Bangkok’s annual smog season had officially begun, according to The Associated Press. Air quality in the region has been getting worse since late 2023. In northern provinces like Chiang Mai, a period of high microscopic dust levels typically starts in late February, when airborne particles build up due to a combination of an inversion layer in the atmosphere and dry weather.

Many residents of Bangkok are not able to work from home, however.

“If I stay home, then I will starve,” 57-year-old motorcycle taxi driver Jarukit Singkomron, who is allergic to the pollution, told AFP. “People like me have to go out to make ends meet.”

Subsidies have been offered to farmers by the Thai government to stop burning, as well as less expensive electric vehicle (EV) packages, Reuters reported. A clean air act is under consideration by lawmakers to reduce pollution from transportation, agriculture and industry.

The prime minister recommended that the government consider limiting fossil fuel-powered vehicles in Bangkok and pointed out that Thailand’s EV policy was an important component of efforts to reduce pollution now and in the future.

“We have a lot of problems with pollution at the moment, so we have to act immediately to reduce the effects on people,” Srettha said, as reported by AFP.

The post Bangkok City Workers Ordered to Work From Home to Avoid Toxic Smog appeared first on EcoWatch.

Parts of an oil spill first detected near the island nation of Trinidad and Tobago on February 7 are drifting into the Caribbean Sea, putting the country’s coral reefs, as well as other nations, at risk.

The spill was determined to have been caused by an overturned barge being pulled by a tugboat called Solo Creed, according to a post by Trinidad and Tobago’s Ministry of National Security.

Monitoring service TankerTrackers.com said the barge and tugboat were on their way to the Grenadines and St. Vincent, reported Reuters.

“The satellite showed that some of it was moving into the Caribbean Sea, as well as some of the modeling,” Allan Stewart, director of Trinidad and Tobago’s emergency management agency (TEMA), told Reuters.

The boat overturned approximately 480 feet off the coast of Venezuela, The Washington Post reported.

A national emergency was declared by Trinidad and Tobago on Sunday, reported The Guardian. At least two schools have been closed amid health concerns, and a cleanup effort has begun.

Prime Minister Keith Rowley told reporters on Sunday that workers were cleaning beaches, working on containing the spill with booms and protecting wildlife, according to The Washington Post.

Parts of the 7.46-mile spill have been spotted moving into the Caribbean in opposite directions, TEMA said, as Reuters reported.

TEMA photographs posted on Tuesday revealed progress in cleaning up beaches in Tobago, with roughly a third of the 9.3 miles of shoreline having been cleaned, Stewart said.

“This is a national emergency and therefore it will have to be funded as an extraordinary expense,” Rowley told reporters, as reported by The Independent. “[W]e don’t know the full scope and scale of what is going to be required. Right now, the situation is not under control. But it appears to be under sufficient control that we think we can manage.”

Rowley said the vessel appeared to be leaking “some kind of hydrocarbon.”

According to officials, divers have been having a hard time containing the spill as concerns over its damage to the area’s ecosystem, as well as tourism, increased.

Oil’s toxic substances can have a lasting impact on coral reefs, fish and other marine life.

Rowley said offers of help have been extended by several countries.

The oil spill happened during one of Trinidad and Tobago’s largest tourist attractions, Carnival season, CNN reported.

“The best part of Tobago’s economy is its tourism, so it is important that we be cognizant that we don’t expose the tourism product to this kind of thing,” Rowley said, according to CNN.

Residents of Lambeau expressed concerns about their health as a stench from the spill filled the air, local media said.

Farley Augustine, the Tobago House of Assembly’s chief secretary, advised residents with respiratory issues to “self-relocate” and use masks.

“Cleaning and restoration can only seriously begin after we have brought the situation under control,” Rowley said, as reported by The Independent.

The post Oil Spill off the Coast of Trinidad and Tobago Drifts Into Caribbean, Threatening Marine Life and Coral Reefs appeared first on EcoWatch.

The latest Census of Agriculture from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) raises concerns over a loss of small farms and a growth in larger farms, while also showing some promise with the growth of renewable energy implementation in agriculture.

The USDA completes a Census of Agriculture every five years to count the nation’s farms and ranches. The latest census, the 2022 Census of Agriculture, revealed that 39% of U.S. land is covered by farms and ranches. The number of farms and ranches is around 1.9 million, a decrease of 7% from the previous 2017 census. While the number of farms decreased, the size of each farm increased 5% to an average of 463 acres.

Most of the farmland, nearly three-fourths, was used for two primary reasons: oilseed and grain production and beef cattle production. Beef cattle production comprised 40% of land use. According to an analysis from Food & Water Watch, the number of animals in factory farms is now around 1.7 billion, up 6% since the last census and 47% since 2002, while the number of small-size dairy farms is only about one-third of the number of smaller dairy farms in 2002.

Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack, who presented the census to the USDA, noted that the trend of fewer but larger farms has had negative impacts on communities. In addition to the decline of smaller farms, the impacts have led to losses in other community staples, such as schools and healthcare, Mother Jones reported.

To change course, Vilsack recommended investments in climate-friendly farming practices that could also provide additional revenue streams for owners of small- to medium-size farms.

“It’s important for us to invest in climate-smart agriculture because that creates an opportunity for farmers to qualify, potentially, for ecosystem service market credits, which is cash coming into the farm for environmental results that can only occur on the farm,” Vilsack said, as reported by Mother Jones. “The farm then creates a second source of income.”

In a press release, Vilsack noted some recent initiatives by the U.S. government to improve the agriculture industry for smaller farmers, including improving local food systems for farmers to sell directly to customers and incorporating renewable energy projects with agriculture.

“All of these actions are enabling America’s farmers to be less reliant on a few large, consolidated monopolies, making farming more viable for the next generation, and making our food system more resilient for everyone who eats,” Vilsack said.

According to the census report, farms and ranches produced $543 billion, an increase from $389 billion generated in 2017. Further, Vilsack said in a press statement that the net farm income during the first three years of the Biden administration was the highest on record.

There were other positive takeaways from the census as well. There was a 15% increase in the number of farms utilizing renewable energy generation compared to the 2017 census, and there was an 11% increase of the number of beginner farmers, or those with 10 or fewer years of experience.

“There is more work to do to ensure we maintain strong momentum in terms of farm income, and to make sure that income is equitably distributed among farms of all sizes so more can stay in business and contribute to their local economies,” Vilsack said. “Today’s report is a wake-up call to everyone who plays a role in agriculture policy or who shares an interest in preserving a thriving rural America — we are at a pivotal moment, in which we have the opportunity to hold tight to the status quo and shrink our nation’s agriculture sector further, or we can choose a more expansive, newer model that creates more opportunity, for more farmers.”

The post USDA Census of Agriculture Shows U.S. Losing Small Farms to Factory Farming, While Gaining in Renewable Energy Use appeared first on EcoWatch.

Having altered ecosystems drastically over the past two centuries, humans are witnessing substantial losses in…

The post Regenerative Fashion: Cultivating a Positive Impact on the Planet appeared first on Earth911.

Have you ever wondered how your waste management and recycling program performance compares with other…

The post How SWEEP Key Performance Indicators Can Change Local Recycling Outcomes appeared first on Earth911.

Trudging across the top of Bromley Mountain Ski Resort on a sunny afternoon in January, Matt Folts checks his smartwatch and smiles: 14 degrees Fahrenheit. That is very nearly his favorite temperature for making snow. It’s cold enough for water to quickly crystallize, but not so cold that his hourslong shifts on the mountain are miserable.

Folts is the head snowmaker at Bromley, a small ski area on the southern end of Vermont’s Green Mountains. The burly 35-year-old sports a handlebar mustache, an orange safety jacket, and thick winter boots that crunch in the snow as he walks. A blue hammer swings from his belt.

It is nearing the end of the day for skiers, but not for Folts. He’ll work well into the evening preparing the mountain for tomorrow’s crowd. Cutting across the entrances to Sunder and Corkscrew, he heads toward a stubby snow gun used to blanket Blue Ribbon, an experts-only trail named in honor of Bromley’s founder, Fred Pabst Jr. The apparatus stands a few feet high, with three legs and a metal head that’s angled toward the sky. Two lines that resemble fire hoses supply the device with water and compressed air, which it uses to hiss precipitation into the air. As the water droplets fall, they coalesce into snowflakes.

“If it was warmer I’d be a yeti,” says Folts, referring to wetter snow that, if conditions were just a bit balmier, would leave him abominably white. But at these temperatures the powder he’d just made bounced lightly off his sleeve. “That’s perfect.”

Yet perfect fake fluff like Folts’ poses a climate conundrum. On one hand, making snow requires enormous amounts of energy, which creates planet-warming emissions. On the other, a warming planet means that artificial snow is increasingly essential to an industry that, while admittedly a luxury, pumps over $20 billion annually into ski towns nationwide. The good news is that, in the face of these growing threats, resorts have been dramatically improving the efficiency of their snowmaking operations — a move they hope will help them outrun rising temperatures.

American ski areas logged more 65 million visits last season. A sizable chunk of those likely came during Christmas week, when a resort can make — or lose — a third or more of its annual revenue. The Martin Luther King Jr. and Presidents Day weekends are similarly vital. But ensuring that there’s a surface to slide on is an increasingly fickle business.

Snowpack in the Western U.S. has already declined by 23 percent since 1955, and climbing temperatures have pushed the snowline in Lake Tahoe, California — which is home to more than a dozen resorts — from 1,200 to 1,500 feet. A recent study found that much of the Northern Hemisphere is headed off a “snow-loss cliff” where even marginal increases in temperature could prompt a dramatic loss of snow.

By one estimate, only about half of the ski areas in the Northeast will be economically viable by mid-century. Research suggests that Vermont’s ski season could be two to four weeks shorter by 2080, while another study found that Canada’s snowmaking needs will increase 67 to 90 percent by 2050. At Bromley, snow guns have been essential for years; without them, the resort’s mid-January trail count would have likely been in the single digits, rather than 31.

Opening terrain, however, comes at a cost. It takes a lot of horsepower to move water up the hill under pressure, and compress the air the guns need to function. Bromley’s relatively small operation, which produces enough snow each season to cover about 135 acres in three or more feet of the stuff, chews through enough electricity each year to power about 100 homes. All that juice adds nearly half a million dollars to the resort’s utility bill.

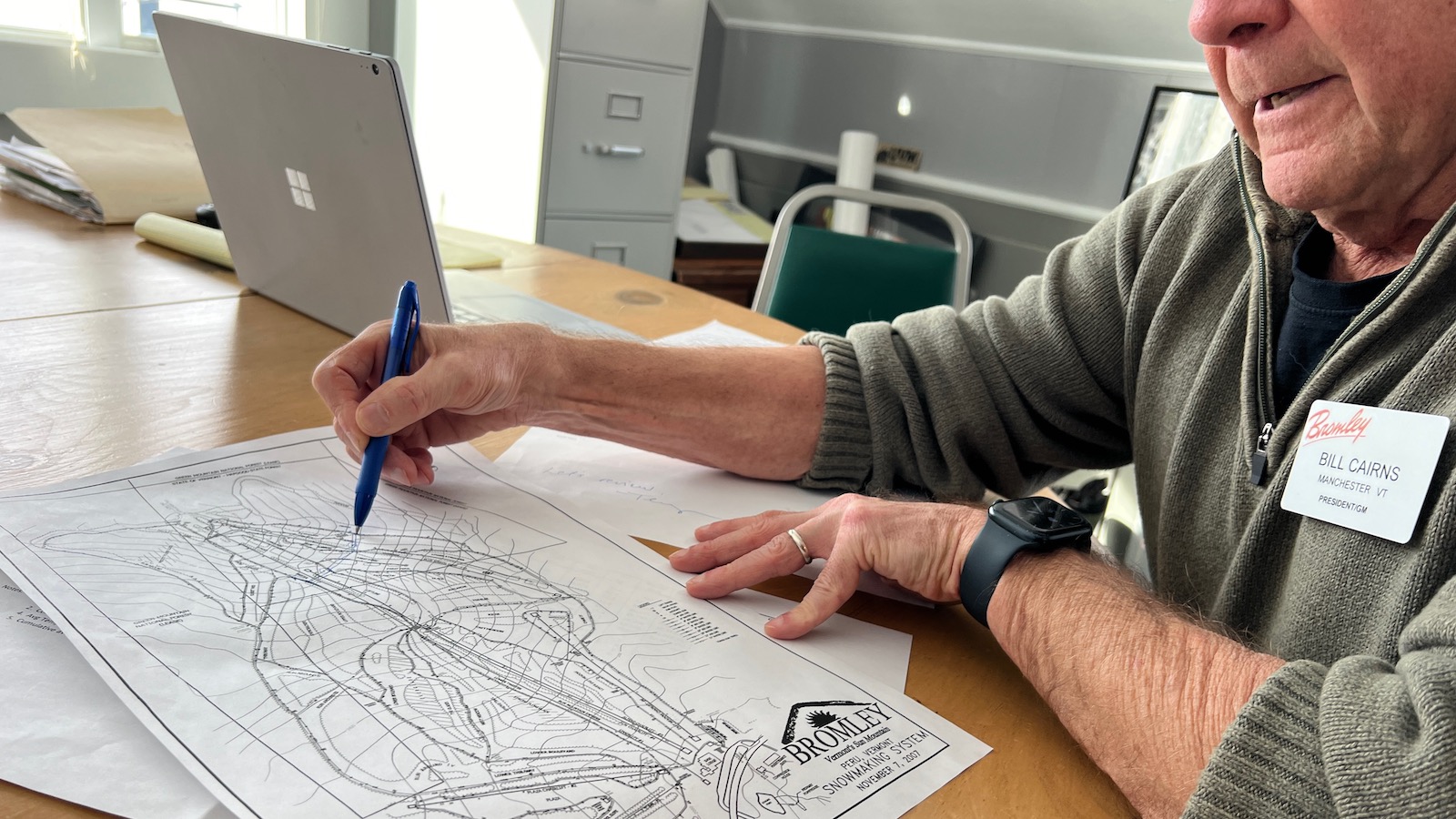

But Bill Cairns, Bromley’s president and general manager, says the system is actually much more efficient than it was just a decade ago. “I used to spend about $800,000,” he says. He’s now able to produce more snow for around half the price. “The reduction in cost with snowmaking has totally been a game changer.”

Powder days start with specks of dust high in the atmosphere. As they fall, water droplets attach to them, forming snowflakes. Ski areas like Bromley replicate this natural process using miles of pipes that feed water and compressed air to hundreds, sometimes thousands, of snow guns scattered across a mountain.

Early guns mixed compressed air and water inside a chamber, and then used air pressure to propel water droplets skyward through a large nozzle. This was the type of system Fred Pabst Jr., of beer family fame, spent $1 million installing in 1965, making his resort one of America’s earliest adopters.

“It was a black art. We knew nothing,” says Slavko Stanchak, whose inventions and expertise have made him a legend among snowmakers. It was an era when energy was relatively cheap and resorts would rent rows of diesel-powered compressors that threw whatever snow they could generate on the hill. But as energy costs rose in the 1990s and early 2000s, so did the impetus to innovate.

“We focused on making the process viable from a business standpoint,” Stanchak says.

He eventually launched a consulting company that helped ski areas, including Bromley, design or improve their snowmaking operations. On the water side of the equation, Bromley spent the 1990s improving its piping network and added a mid-mountain pump to help get H2O from its ponds to its trails. (Much of the water eventually returns to the watershed during the spring melt.) But the amount of water needed to carpet a ski hill in snow remains relatively fixed from year to year, so there are only so many efficiency gains to be had. Compressing air is what really eats into a budget.

“The air is where the little dollar bills fly out,” says Cairns, adding that two diesel compressors can consume a tanker truck of fuel every week.

The 1990s also saw more efficient snow guns come to market. Tinkerers discovered that devices with multiple small holes, instead of a single large aperture, could utilize water, rather than air pressure, to force fluid upward. This allowed them to move the compressed air nozzles to the outside of the barrel, where they would primarily break the water stream into droplets — a far less strenuous function than forcing them out of the gun.

“An old-school hog might use 800 cubic feet per minute [of compressed air]. This one here uses about 70,” Folts says, pointing toward a tower gun from the early 2000s that stands about 15 feet tall and, unlike the ground guns on Blue Ribbon, can’t be easily moved. Up the hill sits a newer model that can get by on closer to 40 cubic feet per minute, or CFM, and a bit farther down the slope is the resort’s latest tool, which under ideal conditions can use as little as 10. That’s a roughly hundred-fold increase in efficiency.

The state-backed Efficiency Vermont program urges resorts to swap in as many of the more efficient devices as possible. “That work got a real big boost in 2014, when we did the ‘Great Snow Gun Roundup,’” explains Chuck Clerici, a senior account manager at the organization. Before then, it had been doing a handful of sporadic replacements. The roundup retired some 10,000 inefficient models statewide, and, overall, Clerici says snowmaking operations are now using about 80 percent less air than they used to.

While Efficiency Vermont doesn’t separate savings that are the result of snowmaking upgrades from, say, those tied to building improvements, it reports that its efforts to help ski resorts use less energy have saved more than a billion kilowatt hours of electricity between 2000 and 2022. That’s nearly a million tons of planet-warming carbon dioxide emissions or the equivalent of taking more than two gas-fired power plants offline for a year.

“The bigger projects we’ve had over the years have been snowmaking projects,” says Clerici. “We don’t have that many instances in the energy-efficiency realm where you can swap something that uses one-fifth of the energy.”

Standing next to the building that houses Bromley’s air compressors, Cairns points to a concrete slab with two manhole covers that once fed massive underground diesel tanks. “Underneath was fuel,” he says. To his right is a large pipe marked where the carbon-spewing generators used to connect to the rest of the snowmaking system. Now it’s cut off.

Bromley is among the many snowmakers that have been able to eliminate, or drastically reduce, its dependence on diesel air compressors. Electrifying the job has also allowed some resorts to incorporate renewable energy. Bolton Valley, in Vermont, features a 121-foot-tall wind turbine. Solar panels now dot the hills of many others, including Bromley, which leases a strip of land beside its parking lot for a solar farm. The array produces more than half the power its snowmaking system consumes.

America’s snowmaking industry has been historically based on the East Coast, where natural snow can be especially elusive. But that’s changing. “We’re doing a lot more work out West,” says Ken Mack, who works for HDK Snowmakers, one of the largest equipment manufacturers. One of the company’s executives recently moved to Colorado to help meet demand.

The snow guns that HDK sells currently may be reaching the limit of how little water and compressed air they use. “We’re probably getting to a point where we’ve gone as low as we can go,” says Mack. That’s required finding gains in other arenas.

One step snowmakers can take, says Mack, is to better track how much energy they use, ideally in real time. He’s in the midst of trying to help revive a metric called the Snowmaking Efficiency Index, or SEI. It’s a measure of how many kilowatt hours it takes to put 1,000 gallons of water worth of snow on the hill, something Stanchek pioneered years ago but never quite took hold. (For reference, under ideal circumstances it takes about 160,00 gallons to cover one acre in one foot of snow.)

If publicly released, such data could provide transparency and allow ski areas to boast about their efficiency. That’s particularly appealing given that sustainability and environmental stewardship are increasingly top of mind for consumers. But because SEI varies considerably from mountain to mountain, and by temperature, it will likely be most effective as a tool for resorts to compete against themselves, rather than each other.

This year, Bromley’s SEI ranged from about 23 in the warm, early weeks of the season to mid-teens when temperatures dropped. Cairns consistently tries to beat those numbers and can monitor them from his office. If the number ever spikes, he can search for an open gun, leaking water line, or other culprit.

“Anything below 20 is really good,” Cairns says. “So we’re trending the right way.”

An arguably more revolutionary development in snowmaking is the move toward automated systems that can be operated almost entirely remotely. One obvious benefit is reducing the need to find people willing to schlep around a mountain in the dead of night, when temperatures can dip into single digits. More importantly, automation allows resorts to ramp snowmaking up and down quickly, which is particularly useful as global temperatures climb.

Snowmaking can occur when the mercury drops to about 28 degrees F (though the process is optimal at around 22 degrees or less); a threshold Mother Nature sometimes crosses for only brief periods. When it does, resorts can take advantage with a press of a button, instead of having to spend the time dispatching a crew out to fire up all those guns. The ability to operate in shorter time windows also means less energy is needed to run pumps and compressors — and get people up and down the mountain.

“You’re done sooner,” says Mack. Where it might take 100 man-hours to cover a trail, automation could cut that to 20 or 30. “It’s absolutely a savings. But it also gives you a little bit of reserve if you need it.”

Europe is far ahead of North America when it comes to automation, in part because governments have subsidized the daunting expense of running electricity and communication lines across a mountain. The cost of installing the technology can quickly run into the millions and, without subsidies, the benefits for American ski areas have been limited largely to smaller mountains in warmer climates, such as in the mid-Atlantic, where it is vital to surviving. But bigger resorts in snowier locales, including Stowe, Stratton, and Sugarbush in Vermont and Big Sky in Montana, have been testing the equipment.

“The future of snowmaking is definitely going to be automation,” says Cairns. “It’s just a lot of money, and nobody really wants to subsidize that yet.”

Bromley is testing one semi-automated gun that could avoid the wiring issue. It uses the existing compressed air supply to spin an internal turbine that creates just enough energy to run a small onboard computer. By monitoring the weather conditions, it can automatically adjust the rate of water and air flow to produce optimal snow.

“Those guns don’t need any power,” says Folts, as he finished adjusting the position of one gun and moved to the next. “That’s kind of another next level.”

Until then, Folts and his crew lumber on into the night, one gun at a time.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Greener snowmaking is helping ski resorts weather climate change on Feb 15, 2024.

This story was originally published by Floodlight, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates the powerful interests stalling climate action.

In his first four weeks in office, Louisiana Republican Governor Jeff Landry has filled the ranks of state environmental posts with fossil fuel executives.

Landry has taken aim at the state’s climate task force for possible elimination as part of a sweeping reorganization of Louisiana’s environmental bureaucracy. The goal, according to Landry’s executive order, is to “create a better prospective business climate.”

And in his first month, Landry changed the name of the Department of Natural Resources, the state agency with oversight of the fossil fuel industry, by adding the word “energy” to its title.

While the United States and other countries have vowed to move away from fossil fuels, Landry is running in the opposite direction.

Landry, who has labeled climate change “a hoax,” wants to grow the oil and gas industry that supports hundreds of thousands of jobs in Louisiana. Environmentalists blame the industry for the pollution that has harmed vulnerable communities in the state and for the climate change tied to increased flooding, land loss, drought, and heat waves in the Gulf Coast state.

A key indicator of where Landry is headed is the choice of Tyler Gray to lead the state’s Department of Energy and Natural Resources. Gray enters the new administration after spending the past two years working for Placid Refining Company as the oil company’s corporate secretary and lobbyist.

Before that, Gray spent seven years with the Louisiana Mid-Continent Oil and Gas Association, or LMOGA, his final two years serving as the lobbying group’s president. During his tenure with LMOGA, Gray helped draft the controversial 2018 law that criminalized protesting near the oil and gas pipelines and construction sites.

At the time, Gray said the law was needed as protection from individuals who attempt to unlawfully interrupt the construction of pipeline projects or damage existing facilities. Greenpeace USA found such laws — enacted in 18 states — were directly tied to lobbying by the fossil fuel industry and resulted in insulating more than 60 percent of the U.S. gas and oil industry facilities from protest.

Anne Rolfes with the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, a grassroots nonprofit focused on accountability in the petrochemical industry, has a grim outlook on Gray’s tenure. Her organization has been involved with many of the protests in question.

“His willingness to suppress people’s rights in favor of that industry is alarming,” Rolfes said.

“He’s been writing laws that favor the oil industry over the rights of people throughout his career,” she added. “But the state has never stood up to the oil industry. Under every administration there is this myopic idea of destroying our state via the oil and gas industry is somehow economic development.”

Neither Landry nor Gray’s office responded to multiple requests for comments.

Gray is one of several former fossil fuel executives Landry has selected to lead Louisiana’s environmental efforts.

Tony Alford, the former co-owner and president of a Houma-based oil-field service company that was accused of spilling toxic waste in a Montana lawsuit, is now the chairman of the Governor’s Advisory Commission on Coastal Protection. And Benjamin Bienvenu, an oil industry executive and petroleum engineer, is serving as the commissioner of conservation within the Department of Energy and Natural Resources.

Landry also tapped Aurelia Giacometto to lead the state’s Department of Environmental Quality. It was reported that Giacometto, the first Black woman to serve in the position, had ties with skeptics of climate science when she served under then-President Donald Trump as head of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. She currently sits on the board of a coal manufacturing company.

And Landry’s pick for the state’s new leader for the Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, Madison Sheahan, doesn’t have a background in wildlife — or fisheries. She enters the job after serving as the executive director of the South Dakota Republican Party and managing Trump’s re-election campaign in that state. The agency led by Sheahan is one of the state entities responsible for investigating oil spills.

At a recent press conference, Landry said he seeks to expand oil and gas refining in Louisiana, seeing it as the only way to increase job opportunities for the middle class.

For environmentalists, these are worrying signs for a state that is the site of a boom in proposed liquified natural gas facilities and carbon capture projects that they say threaten to increase Louisiana’s already high contribution of climate-changing greenhouse gases.

In late January, President Joe Biden announced his administration was halting approvals of new liquified natural gas export facilities to examine the need for the additional capacity and the environmental impact of such projects. The temporary delay reportedly affects five projects in Louisiana and one in Texas.

Landry’s moves weren’t unexpected, advocates say, given his past actions as state attorney general and his combative stance toward environmental justice issues.

Gray’s appointment is “disappointing but not surprising,” said Jackson Voss, climate policy coordinator for the Alliance for Affordable Energy.

“Unfortunately, from our perspective, the history of the [Louisiana] Department of Natural Resources has always been very deeply connected with the oil and gas industry,” Voss said. “In some ways it helps us, because there’s not going to be very many surprises about where Secretary Gray will align on certain issues.”

In its latest report, Human Rights Watch highlighted the environmental harms and health-related issues the oil and gas industry is accused of inflicting on predominantly Black communities in the southeast Louisiana corridor known as Cancer Alley. The group is asking state leaders to phase out fossil fuel production and to halt any new developments or expansions to existing fossil fuel and petrochemical facilities.

Author Antonia Juhasz interviewed dozens of residents living in Cancer Alley who talked about miscarriages, high-risk pregnancies, infertility, respiratory issues and a multitude of other health impacts in their communities. They attribute the maladies to years of pollution and dangerous emissions from the high concentration of polluting industries, especially in southern Louisiana.

“The fossil fuel and petrochemical industry has created a ‘sacrifice zone’ in Louisiana,” Juhasz, senior researcher on fossil fuels at Human Rights Watch, said in a prepared statement. “The failure of state and federal authorities to properly regulate the industry has dire consequences for residents of Cancer Alley.”

As the state’s attorney general, Landry pushed lawsuits against restrictions the Biden administration tried to implement on offshore oil lease sales and the cancellation of the Keystone XL pipeline.

He also sued over the Environmental Protection Agency’s push to better regulate emissions from oil and gas facilities in Cancer Alley.

A Trump-appointed federal district court judge in western Louisiana recently sided with Landry on that lawsuit. U.S. District Judge James Cain said in his opinion that the federal agency’s enhanced oversight of proposed projects in Cancer Alley communities overstepped its powers and that it was “imposing an improper financial burden on the state.”

As attorney general, Landry also sued to obtain correspondence between EPA, environmentalists and certain journalists.

As governor, Landry has opposed Biden’s climate initiatives, including the push to increase manufacturing of electric vehicles. And Landry has claimed that boosting renewable energy in Louisiana, including solar and wind, would force the state into “energy poverty.”

Landry’s pick of Gray was lauded by the president of the Louisiana Mid-Continent Oil and Gas Association. In a prepared statement, Mike Moncla praised Gray for knowing their industry “backwards and forwards.”

“This appointment marks the state of a new era for our state’s oil and gas industry,” Moncla wrote. “We know that he will be an incredible asset for our industry.”

At LMOGA, Gray also pushed back at any efforts to limit offshore drilling and domestic energy production to reduce planet-warming emissions. Gray said the country needed “sound, science-based policies” and solutions to address climate change that also promote “domestic energy development” while not stifling the state’s economy and job market.

LMOGA is a staunch supporter of carbon capture and sequestration. The agency Gray now leads recently received primary regulatory oversight from the federal government for the wells used to pump carbon dioxide underground for permanent storage.

The technology is being touted as the solution to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, but debates are ongoing over its safety and effectiveness.

Environmental advocates argue that carbon capture and storage is just a ploy to prolong the life of the fossil fuel industry instead of transitioning to cleaner energy sources like wind and solar. They lack confidence in the state’s ability to properly permit carbon capture projects with Gray at the helm.

“With Gray’s appointment and then an already heavily underfunded and understaffed agency, it very much feels like they’ll be sending those permits through instead of truly evaluating them one by one,” said Angelle Bradford, a spokesperson with the Delta chapter of the Sierra Club. “It’s once again the usual good-old-boy mentality where we’re putting people in positions who not only won’t follow the rules but create rules that make it harder for the other side, which is us.”

She added, “Louisiana is not taking the climate crisis seriously.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline When a climate denier becomes Louisiana’s governor: Jeff Landry’s first month in office on Feb 15, 2024.