The Gloria Barron Prize for Young Heroes celebrates inspiring young people from across the U.S….

The post The Gloria Barron Prize for Young Heroes Encourages Youth to Protect the Planet appeared first on Earth911.

The Gloria Barron Prize for Young Heroes celebrates inspiring young people from across the U.S….

The post The Gloria Barron Prize for Young Heroes Encourages Youth to Protect the Planet appeared first on Earth911.

As recycling and reuse programs evolve, you can positively impact your community by learning how…

The post Tap The SWEEP Standard To Talk With Your Community Leaders About Waste Generation, Prevention and Recycling appeared first on Earth911.

This story was produced in partnership with Atlanta News First.

The bruises on Alexandria Pittman’s body wouldn’t go away. Nor would the aches that plagued her at her new job at a distribution center in Lithia Springs, a small town 17 miles west of Atlanta, sorting and repackaging boxes containing medical devices. She was convinced the symptoms were connected to the job.

Pittman had applied to the position at the warehouse, run by the medical supply company ConMed, after learning about the opening from her fiancé, Derek Mitchell, who delivered products there. Every day she’d come home and complain to him about the mysterious aches and marks. At first, Mitchell tried to reassure her, guessing that the bruises were probably from bumping up against something. “I really didn’t think nothing of it,” he recalled.

Then, in the spring of 2019, came a surprising revelation. ConMed managers announced that the seemingly innocuous products in the boxes they were packaging had been sterilized with ethylene oxide, which the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency considers a carcinogen and is linked to lung and breast cancers as well as diseases of the nervous system. Suddenly, Pittman began connecting the dots between her symptoms and those of her colleagues. It would later emerge that at least 50 warehouse workers experienced a slew of health effects tied to ethylene oxide exposure, including seizures, vomiting, and trouble breathing. Ambulances were routinely called to the facility after workers collapsed, convulsed from seizures, or broke out in hives. Several — including Pittman — developed cancer.

Since ConMed came clean about the workers’ exposure to ethylene oxide, Pittman has suffered four strokes and had brain surgery. She’s currently undergoing chemotherapy for myeloma, according to multiple claims she has filed with the Georgia State Board of Workers’ Compensation for help paying her medical bills. After the second stroke, Mitchell was unable to care for her, and she moved in with her mother where she now lives. Mitchell and Pittman had planned to marry, but the $5,000 ring Mitchell purchased now sits collecting dust.

“It just corrupted everything that she ever wanted to do in life,” said Mitchell. “She can’t talk, and she’s being fed through a tube.”

The ethylene oxide that Pittman and dozens of her coworkers were exposed to wasn’t supposed to have made it to the warehouse at all. At a sterilization plant 12 miles down the road, the chemical had been used to fumigate products before they were sent to the warehouse, a standard procedure for making sure that medical equipment is antiseptic and safe to use in hospitals across the country. More than 50 percent of all U.S. medical supplies are sterilized by ethylene oxide, due to the chemical’s unique ability to penetrate porous surfaces without causing damage.

But over the past few years — beginning with findings by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, or OSHA, in 2019 and Georgia’s Environmental Protection Division, or EPD, in 2020 — regulators have learned that some amount of ethylene oxide travels out of sterilization facilities on the treated products. In the hours and weeks following application, the chemical evaporates, or off-gasses, turning the buildings where these products are stored into potentially significant sources of toxic air pollution — particularly for workers like Pittman who handled the boxes directly.

The dangers came as a surprise to warehouse workers and regulators alike. Georgia EPD officials had originally only set out to monitor ethylene oxide levels around the industrial sterilization facilities fumigating medical equipment. The EPA had just published modeling that suggested high levels of cancer risk around the country’s medical sterilization facilities, and Georgia regulators wanted to assess the plants in their jurisdiction. (The modeling incorporated the results of a 2016 study that found ethylene oxide to be 30 times more toxic to adults and 60 times more toxic to children than previously known.)

After finding elevated levels of ethylene oxide outside of a Becton Dickinson sterilization plant in Covington, a city southeast of Atlanta, officials asked a state judge to temporarily shut the operation down while further testing took place. As part of a consent decree reached in October 2019, the company would not only have to install new technology at its sterilization plants to reduce its emissions, but also test the air coming from its warehouse to ensure that emissions were below the legal limit there as well. The results of this testing showed that the warehouse was emitting nearly 5,600 pounds of ethylene oxide per year — about nine times as much as the sterilization facility when it was still operational, and higher than almost a third of all sterilizer plants in the country. (Georgia requires an industrial facility emitting more than 4,000 pounds of a hazardous air pollutant per year to obtain a permit from the state allowing it to do so.)

“We basically cited the facility for failure to have an air permit, and we required them to control their air emissions,” recalled Jim Boylan, head of the air protection branch at the Georgia Environmental Protection Division, in an interview. “That’s how it all started.”

When he realized that Becton Dickinson couldn’t be the only company storing medical products recently sterilized with ethylene oxide, Boylan assigned several engineers in the EPD’s inspection program to search for similar operations. They had their work cut out for them — because the risk of exposure at these warehouses is such a new concern, there is no comprehensive public or government data on the identity, location, or number of these facilities in Georgia or any other state, let alone any kind of risk assessments. Inspectors scoured the internet and made in-person visits to warehouses to identify potential sources of emissions. Their research revealed that in some cases, warehouse operators were aware that the medical devices they stored were releasing a carcinogen that could be poisoning their workers.

All told, interagency emails obtained by Grist through a Freedom of Information Act request show that inspectors initially identified seven warehouses in Georgia storing products that had been sterilized with ethylene oxide; four emitted enough of the chemical to require air permits and the installation of emission-reduction equipment. Those facilities are on track to receive their permits in the coming months. While these measures may protect residents who live near the warehouses, they don’t guarantee the protection of the workers who may be experiencing exposure day in and day out. The responsibility of safeguarding workers falls to OSHA, which has not investigated ethylene oxide levels at three of the four warehouses that Georgia regulators have identified as requiring permits.

Frances Alonzo, a spokesperson for the federal Department of Labor, said that OSHA evaluates employers “on a case-by-case basis based on OSHA standards, employer records, interviews, observations on a walk-through, measurements, and air sampling.” (In a follow-up email, Alonzo told Grist that OSHA’s ethylene oxide standards were established in 1984 and that the agency does not have plans to update it.) The agency focuses its resources on workplaces where employees are in imminent danger and conducts follow-up investigations to ensure any previously identified violations have been addressed.

In the ConMed case, after an initial investigation in 2019 identified a slew of violations, OSHA conducted two follow-up investigations. Those inspections revealed “no violations of OSHA standards or serious hazards,” Alonzo said. In 2020, Pittman and dozens of her coworkers filed a lawsuit against ConMed and the sterilization company that shipped products to the warehouse, but the claims were later dismissed by the judge.

Despite all the work still to be done by regulators, Georgia is relatively far ahead of the curve on addressing ethylene oxide emissions from warehouses. Most other states have yet to examine whether warehouses in their jurisdiction are storing sterilized products — and if emissions from the facilities put workers and nearby residents at risk. A review of public records submitted to the EPA and state regulators revealed that there are dozens of such warehouses across the country, suggesting there are thousands of workers like Pittman, unknowingly and routinely exposed to ethylene oxide. These nondescript facilities are hiding in plain sight in places as disparate as Quincy, Massachusetts; Richmond, Virginia; and Tempe, Arizona.

Warehouses that store products sterilized with ethylene oxide pose “a deep threat to communities, and unfortunately, because we don’t really know or have as much information as we should about where those warehouses are, it’s an unknown source of major ethylene oxide emissions,” said Marvin Brown, an attorney with the environmental nonprofit Earthjustice.

Grist contacted the environmental agencies of 10 states that are home to multiple medical supply sterilization facilities. Most agencies said that they did not regulate warehouses that stored products sterilized with ethylene oxide and pointed to federal regulations that require them to oversee sterilization and manufacturing facilities — but not warehouses or distribution centers. Apart from Georgia, the South Coast Air Quality Management District, a regulator that serves a portion of Southern California, is a lone outlier. The agency is currently in the process of finalizing a rule requiring warehouses that store ethylene oxide products to conduct air quality monitoring.

The federal government, for its part, hasn’t yet addressed major loopholes that exempt warehouses from emissions rules. Because ethylene oxide is toxic in such small amounts, officials have had trouble regulating emissions from the sterilization facilities themselves, in many cases permitting emissions that they later discover generate levels of cancer risk that exceed federal public health standards.

While the EPA introduced regulations to reduce ethylene oxide emissions from sterilization facilities last year, its rules only apply to warehouses when they are located on the same property as sterilization facilities. But not only do many companies store their products at warehouses tens or even hundreds of miles away, they also often contract third-party logistics providers to do the job for them. That means products may be warehoused at facilities owned by subsidiaries or entirely separate logistics firms. Some companies have reported using FedEx facilities to store sterilized products. To make matters more complicated, sterilizers have largely been unwilling to disclose the locations of their storage facilities, citing those details as “confidential business information” not subject to public disclosure, according to records submitted to the EPA.

Environmental advocates and public health experts interviewed for this story worried that these informational gaps as well as the findings in Georgia could indicate a substantial and invisible public health threat affecting communities across the country — and one that the EPA should take greater effort to regulate.

“Four years after the stunning discovery of warehouse emissions in Georgia, the EPA has failed to propose standards to address this source of uncontrolled emissions,” read a comment letter submitted to the EPA last year and signed by 16 environmental, public health, and labor groups, including Earthjustice and the Union of Concerned Scientists. It is also concerning, they wrote, that most sterilization companies fail to publicly disclose the locations of these warehouses.

“If [warehouses] are significant sources of ethylene oxide, we believe they should be covered by the [EPA’s sterilizer] rule,” Darya Minovi, a senior analyst at the Union of Concerned Scientists, told Grist. “I don’t think that the EPA provided a strong enough rationale for why that wouldn’t be considered.”

The agency is expected to finalize its sterilizer rule in early March. Environmental attorneys said the EPA’s reasoning for overlooking warehouses may come down to legalese. The agency issues regulations based on categories of pollution sources defined in amendments to the Clean Air Act in the 1990s. Since off-site storage facilities weren’t clearly defined in the law decades ago, whether the EPA can regulate them with a rule targeting sterilization facilities is an open question.

A spokesperson for the EPA did not comment on why the agency isn’t including warehouses in its current sterilizer rule but said that it has already determined the levels of ethylene oxide that would be harmful to workers and plans to address emissions in a separate pesticide rule before the end of the year.

Ira Montgomery takes 26 pills a day. There’s one to calm the spasms that ripple through his muscles, another to lower his blood pressure, and yet another to make sure his body doesn’t reject a liver that doctors transplanted after diagnosing him with cancer.

The 51-year-old traces his problems to the years he spent working at the ConMed warehouse. The facility sprawls out over an area the size of five football fields and has rows of shelves that store wooden pallets, each containing medical devices sterilized at a facility owned by Sterigenics about 30 minutes away in Smyrna, Georgia. The products are stored anywhere from a few weeks to several months before they are shipped off to hospitals for use in life-saving procedures.

In records submitted to the EPA, Sterigenics responded “No” to a question about whether products sterilized at its facilities are shipped to a warehouse, since ConMed contracts with Sterigenics to sterilize products. Given this, the presence of ethylene oxide emissions at the ConMed warehouse only became public knowledge due to Georgia regulators’ efforts. The 7-acre warehousing facility in Lithia Springs had neither state permits nor any protective gear for workers between 2008 and 2019, when Montgomery worked there.

Until an inspection by OSHA in 2019, the 3,500 workers at the warehouse were unaware that the products had been sterilized with a dangerous chemical. Dozens of Montgomery’s and Pittman’s coworkers mysteriously developed rashes, had trouble breathing, and fainted; many had seizures. When Nick Jackson began experiencing seizures in 2007 and eventually died in 2013, ConMed managers told his wife the fluorescent lights at the warehouse were to blame. They later informed his doctors that there were no occupational hazards at his workplace.

Similarly, when Essence Alexander opened a box containing products sterilized with ethylene oxide, her right arm broke out in hives and her body began to itch. Warehouse managers called an ambulance, but when paramedics arrived they were not informed that products at the warehouse were emitting a toxic chemical that could have triggered the reaction. In another case, when a worker broke out in hives all over her body, a manager told paramedics the worker had “an allergic reaction to a cookie,” according to legal filings.

Michael Yeh was working as a medical toxicology fellow at Emory University’s School of Medicine in 2021 when a dozen ConMed workers visited the center. As he got to know these patients better, Yeh began to notice certain patterns in their symptoms. Many felt fine on the weekends, but as soon as the work week rolled around, they developed headaches in the afternoon. Once they got home, the pain would subside. There were other common complaints as well: an irksome cough, itchy eyes, and inflamed nasal passages. These workers weren’t looking for a cure for their conditions, Yeh recalled, but an opportunity to understand how their exposure to ethylene oxide may have affected their health.

“There is no antidote to inhaling ethylene oxide,” Yeh said in an interview. “But they wanted us to hear their story and to document in a medical record what they were experiencing so that there’s documentation of what happened to them.”

ConMed warehouse managers attributed these health effects to a range of unrelated issues, according to a lawsuit filed by about 50 workers in 2020. In filings with the court, the company has argued that the workers did not provide sufficient evidence about their individual exposures and subsequent ailments. Since Pittman, Montgomery, and the other plaintiffs submitted multiple claims to the Georgia Workers’ Compensation Board, ConMed has also claimed that the workers have foregone other avenues to air their grievances. The workers are attempting an “end run around the Workers’ Compensation Act … based on a smattering of vague factual allegations interspersed among a series of legal conclusions,” the company claimed in filings.

In total, the lawsuit counts approximately 50 instances of ambulances being called to the warehouse between 2007 and 2019. A Grist review of 911 call records shows that since 2016, ambulances were dispatched to the ConMed warehouse to treat employees on at least 22 occasions. Multiple workers reported similar health effects: seizures, losing consciousness, vomiting, and trouble breathing. All of these symptoms are triggered by high-dose exposure to ethylene oxide. According to medical management guidelines developed by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, which develops profiles for hazardous substances, ethylene oxide is a central nervous system depressant, and acute exposure to it “can result in diverse neurologic manifestations including seizures, loss of consciousness, and coma.” Exposure to lower concentrations can cause nausea and vomiting, while exposure via skin may cause “inflammation with redness of the skin, blisters, and crusted ulcerations.”

Due in part to these risks, OSHA has set acceptable ethylene oxide exposure limits for workers. The federal agency requires companies to inform workers if they are exposed to more than 0.5 parts per million, or ppm, of ethylene oxide and take measures to reduce exposure when levels are above 1 ppm.

OSHA’s efforts to investigate ConMed’s storage center in Lithia Springs in 2019 point to the warehouse owners’ anxieties over the possibility of being regulated. Grist reviewed OSHA complaint records about the facility and found that federal inspectors’ efforts to sample the indoor air were repeatedly rebuffed.

“The employer was not forthcoming in providing the requested documentation,” the complaint read, adding that two subpoenas had been issued to the company to request information about working conditions, but that the company lawyer rejected both. The initial complaint alleged that airborne ethylene oxide inside the warehouse was causing workers to experience “headaches, burning eyes, itching eyes, cough, and chest pains.” It took five months for regulators to get access to the facility and take air samples and another two months to publish the results.

Those results ultimately indicated that ethylene oxide was present in the air at ConMed, but not at levels that breach federal standards. In handwritten notes attached to the complaint file, an OSHA inspector noted that managers instructed workers not to open packages during the inspection, raising the possibility that managers altered operating procedures on that day. “They didn’t know I can see them,” the inspector wrote.

“Did they change their practices when they knew the inspectors were coming?” Yeh wondered, noting that it would be easy for the company to make adjustments if it knew the inspection date in advance.

The investigation also found that warehouse managers had removed an indoor air quality monitor because it routinely recorded levels between 3 and 5 ppm and beeped loudly. The levels of ethylene oxide were so high, the workers claimed, that the cardboard packages wrapped in plastic shrink-wrap became wet. (Ethylene oxide converts into ethylene cholohydrin and ethylene glycol when it interacts with plastic, and the lawsuit claims that the wet boxes were evidence of the high levels of ethylene oxide that the products were off-gassing.)

OSHA fined ConMed $7,800 for failing to inform workers of their high exposure to ethylene oxide and required the company to install equipment that reduced levels of the chemical. ConMed complied by opening bay doors for better ventilation and installing a stationary air quality monitor, but the monitor continued to detect high ethylene oxide levels.

The workers’ lawsuit claims that the products were off-gassing dangerous levels of ethylene oxide in part because Sterigenics, the sterilization company that shipped products to the ConMed warehouse, was using a sterilization method that requires overapplication of the chemical. Ethylene oxide is an effective disinfectant because even at low levels it can eliminate microbes effectively, but different volumes of the chemical may be required to properly disinfect different products. (The amount of ethylene oxide required to sterilize a product is based on regulations by the Food and Drug Administration.)

Because companies often sterilize different types of products all in one fell swoop, they end up gassing them with more ethylene oxide than is required. The lawsuit claims that Sterigenics used this process — called “overkill” in industry parlance — to sterilize more products quickly. The sterilized products are supposed to be held for several hours to days to allow the ethylene oxide to off-gas before they are sent to warehouses for storage, but the lawsuit claims that Sterigenics rushed this process to increase profits. As a result, the products that were trucked to the warehouse had higher levels of ethylene oxide than anyone would have had reason to suspect at the time.

“The method of sterilization has been to over sterilize,” said Brown, the Earthjustice attorney.

“The result for communities is that they are exposed to higher amounts of ethylene oxide, because more ethylene oxide is being used than necessary.”

Sterigenics did not respond to specific questions about its sterilization methods. In an emailed statement, Kristin Gibbs, a spokesperson for the company, noted that Sterigenics sterilized products provided by ConMed on a contract basis “as required by FDA regulations and standards.”

“The facility in Lithia Springs belongs to ConMed — not Sterigenics — and as such, the facility, the employees working in that facility, and those employees’ working conditions are under the control of and are the responsibility of ConMed,” she added.

In 2019, after OSHA investigated and the EPA identified the Sterigenics facility as a major source of ethylene oxide emissions, workers at the ConMed warehouse began trying to take precautions. Pittman asked her fiancé to buy her a mask, but when she wore it at work, the lawsuit alleges that managers told her not to because she was “scaring” others. Several workers were fired after they began raising concerns about the levels of ethylene oxide at the facility.

Since the EPA hasn’t proposed specific regulations for warehouses, Boylan, the Georgia EPD air chief, said states “should work closely with their warehouses to gather site-specific information on ethylene oxide emissions and try to calculate the risk associated with those emissions.”

“Georgia has done kind of above and beyond, because we thought there were possible risks to nearby communities, and we thought the risks were too great,” said Boylan.

In January, the workers elected to drop ConMed from the lawsuit in part because some of their claims were dismissed in 2022 by the judge presiding over the case. Since the workers had filed claims with the Georgia Workers’ Compensation Board, they were barred from seeking redress through the courts. The judge also dismissed certain claims against Sterigenics, but the company remains a party to the lawsuit. “Sterigenics is vigorously defending the limited surviving claims against it,” said Gibbs, the Sterigenics spokesperson.

Since the lawsuit was filed in 2020, four workers who signed up as plaintiffs have died. Mitchell, Pittman’s fiancé, said that working at the ConMed facility completely changed the trajectory of her life. She was a friendly person, always smiling, but the health complications have dimmed the light in her eyes.

“She was proud of her job and how she had moved up,” said Mitchell. “She always talked about how sad it was and how it hurt her. She was just trying to earn a living and do her job.”

Editor’s note: Earthjustice is an advertiser with Grist. Advertisers have no role in Grist’s editorial decisions.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline An invisible chemical is poisoning thousands of unsuspecting warehouse workers on Feb 29, 2024.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — the federal agency that monitors diseases and establishes guidelines to protect human health — published a paper last month that shows cases of Lyme disease jumped nearly 70 percent nationwide in 2022. But what looked like an alarming spike in disease was actually the result of smarter disease surveillance that better reflects what’s happening on the ground.

The CDC revised its Lyme reporting requirements in 2022, making it easier for states with high infection rates to report those cases. The report, the first published analysis of the new data collection guidelines, demonstrates the crucial role efficient surveillance plays in better understanding the scope of infectious disease in the U.S. — and what more must be done to safeguard public health as climate change fosters the proliferation of ticks.

“Disease surveillance that is interpretable and is standardized is integral to being able to understand how disease frequency is changing, and if it’s changing,” said Kiersten Kugeler, a CDC epidemiologist and lead author of the paper. She noted that climate change will complicate the already difficult task of monitoring and controlling diseases such as Lyme. Cases in some areas will continue rising while declining in others as parts of the U.S. become more amenable, or hostile, to ticks. “It’s not going to be straightforward,” Kugeler said. “It’s going to be incredibly important to have good surveillance to be able to understand how climate is affecting risk of disease.”

Studies have documented significant shifts in Lyme trends across the country. The illness is caused by the bite of a black-legged tick and causes symptoms that range from flu-like and mild to neurological and debilitating, depending on how quickly the disease is diagnosed. Cases doubled in the three decades between 1990 and 2020. Many researchers, including CDC employees, say climate change is one factor behind that precipitous rise. Environmental changes such as urban sprawl and swelling populations of white-tailed deer, among other drivers, also play a role.

Warmer winter temperatures have coaxed black-legged ticks into regions that have historically been too harsh for the blood-sucking arachnids. Meanwhile, milder spring and fall seasons have given the pests more time to breed. Lyme is a portent of climate-driven diseases to come. But, as it has spread into new areas and infected more people, the CDC has struggled to capture the full impact.

In 2022, the agency redoubled its disease surveillance efforts, with a special emphasis on vector-borne disease. As part of that push, the CDC loosened its Lyme disease reporting requirements in the Northeast, mid-Atlantic, and upper-Midwest, where cases are high. Public health departments in those areas no longer have to track down the clinical details of each positive Lyme test, such as a patient’s symptoms and when they began, and doctors can skip the labor-intensive process of recording and reporting them. Now, a positive laboratory test is sufficient. Eliminating these steps takes the onus off doctors and local public health authorities and puts it on state health departments, which are typically better equipped to handle it.

“We have a lot of behind-the-scenes data management that’s new with this Lyme disease surveillance system,” Rebecca Osborn, a vector-borne disease epidemiologist at the Wisconsin Department of Health Services. But overall, she said, “it has gotten quite a bit less burdensome.”

The new system runs the risk of including information on people who no longer show symptoms but are still testing positive for the bacteria, which can linger in the blood for years after the infection has gone. But those cases likely comprise a small fraction of the overall data, the CDC said. In areas where Lyme remains rare, providers must continue reporting clinical information for each case.

These relatively modest changes to the case definition requirements unearthed 62,551 cases of Lyme nationwide. That’s 1.7 times the annual average reported from 2017 to 2019.

Still, most cases of Lyme disease in the U.S. go unreported. Studies based on health insurance records estimate that roughly 500,000 cases are diagnosed every year. Those reported by states to the CDC in 2022 comprise less than one-fifth of that. Elizabeth Schiffman, an epidemiologist with the Vector Borne Diseases Unit at the Minnesota Department of Health, said figuring out how to capture every case is nearly impossible and perhaps besides the point.

“No system is ever perfect,” she said, “we’re always going to miss something, we’re always going to count something that probably shouldn’t be counted.” If the CDC could use the data it collects every year under its new system to measure the overall impact of Lyme, Schiffman said, then the number of cases it already knows about may be enough.

“If what we are able to capture is able to give us an idea of where things are happening, how things are changing, and inform good public health actions, then it could be argued that we don’t need to count every case.”

The data deficit and lack of standardization among states becomes more of a problem when researchers try to tease out the impacts of climate change on the disease. The CDC argues that in regions where Lyme incidence is still relatively rare, the updated surveillance system doesn’t make sense. Doctors and local health departments in those areas still need to collect clinical information on every potential Lyme patient, because each case is a revealing datapoint rather than a statistic in a larger trend. But the burdensome requirements in low-incidence areas muddy efforts to detect the role of climate change in how black-legged ticks may be migrating, said Richard Ostfeld, a senior scientist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies who researches tick-borne illnesses.

The prevalence of Lyme disease typically falls along geographic lines. Counties in the upper Midwest and Northeast report tens of thousands of cases each year, while those in the Southeast and South report hundreds. Although the CDC’s revised reporting guidelines more accurately revealed the extent of Lyme disease in areas with a high prevalence, the implementation of the system over time may obscure growth of the disease elsewhere. The new guidelines “would tend to bias your estimate of geographic trends toward more growth in incidence in northern parts of the country as opposed to southern parts of the country where you’re still being very conservative,” Ostfeld said. “It complicates matters for those trying to understand the role of climate change.”

North Carolina, for example, a state long classified as low-incidence, was among five states with the highest number of Lyme disease-related insurance claims in 2016, according to one analysis. But the disease reporting there, said Noah Johnston, director of the Lyme awareness group Project Lyme, still isn’t where it needs to be. “There’s an expectation that tick populations in North Carolina are not as high as they are in the Northeast,” he said.

The benefits and drawbacks of the CDC’s updated surveillance highlight the difficulties of tracking and controlling infectious diseases under climatic conditions that are rapidly shifting the distribution of disease carriers. Incremental adjustments to the status quo might not be enough to keep up with the growing scale of disease risk. “We’re likely going to see more and more cases of these diseases and more and more diseases that are going to affect not just our population in the U.S., but globally,” said Osborn. “Public health in general needs to become a little more proactive in our responses. We’re still working on that as a field.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline As ticks spread, the US is getting closer to understanding the true extent of Lyme disease on Feb 29, 2024.

Nano- and microplastics (NMPs) have become so pervasive in air, water and soil that they have made their way into the bodies and blood of humans and animals.

While many methods have been attempted to remove the tiny plastic particles, a new study has found that a simple solution for reducing their presence in drinking water may be to boil it, as when you make a cup of coffee or tea.

In fact, filtering and boiling tap water containing calcium carbonate could help remove almost 90 percent of the plastics, a press release from the American Chemical Society (ACS) said.

“Tap water nano/microplastics (NMPs) escaping from centralized water treatment systems are of increasing global concern, because they pose potential health risk to humans via water consumption. Drinking boiled water, an ancient tradition in some Asian countries, is supposedly beneficial for human health, as boiling can remove some chemicals and most biological substances,” the study said. “Boiling hard water… can remove at least 80% of polystyrene, polyethylene, and polypropylene NMPs size between 0.1 and 150 μm.”

The side effects of NMPs on humans are still being investigated, but recent studies indicate that their ingestion could impact the gut microbiome, the press release said. While some advanced water filtration systems are able to capture the plastic bits, less expensive strategies are necessary in order to help reduce their passive consumption on a larger scale.

In order to find out if boiling water could help effectively remove NMPs from soft and hard tap water, the research team collected hard water samples and “spiked them” with various amounts of NMPs. They boiled the water for five minutes, then allowed it to cool. When naturally mineral-rich hard water is boiled, it forms a chalky calcium carbonate substance known as limescale. The researchers then measured the remaining plastic content floating in the water.

The results indicated that crystalline structures — or “incrustants” — formed as the temperature of the water increased and encapsulated the NMPs.

Eddy Zeng, one of the authors of the study, said the incrustants would build up over time as limescale usually does, and could then be scrubbed clean to remove the plastics. Zeng explained that any remaining incrustants could be removed by straining them through a coffee filter or other simple filter.

The experiments found that harder water produced a more pronounced encapsulation effect. For example, boiling a water sample with 300 milligrams of calcium carbonate in each liter removed as much as 90 percent of the free-floating NMPs. Roughly 25 percent were removed by boiling soft water containing less than 60 milligrams of calcium carbonate per liter.

The researchers said the results indicated that boiling water could be an easy and effective way of reducing NMP ingestion.

“This simple boiling-water strategy can ‘decontaminate’ NMPs from household tap water and has the potential for harmlessly alleviating human intake of NMPs through water consumption,” the authors wrote in the study.

The post This Simple Solution Can Help Reduce Microplastics in Your Drinking Water appeared first on EcoWatch.

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has announced a last wave of more than $1 billion for the cleanup of Superfund hazardous waste sites from coast to coast.

The most recent phase of Superfund cleanup is part of a total of $3.5 billion allocated for the work, a press release from the EPA said. More than $2 billion has already been deployed for cleanup activities at 150-plus sites on the Superfund National Priorities List.

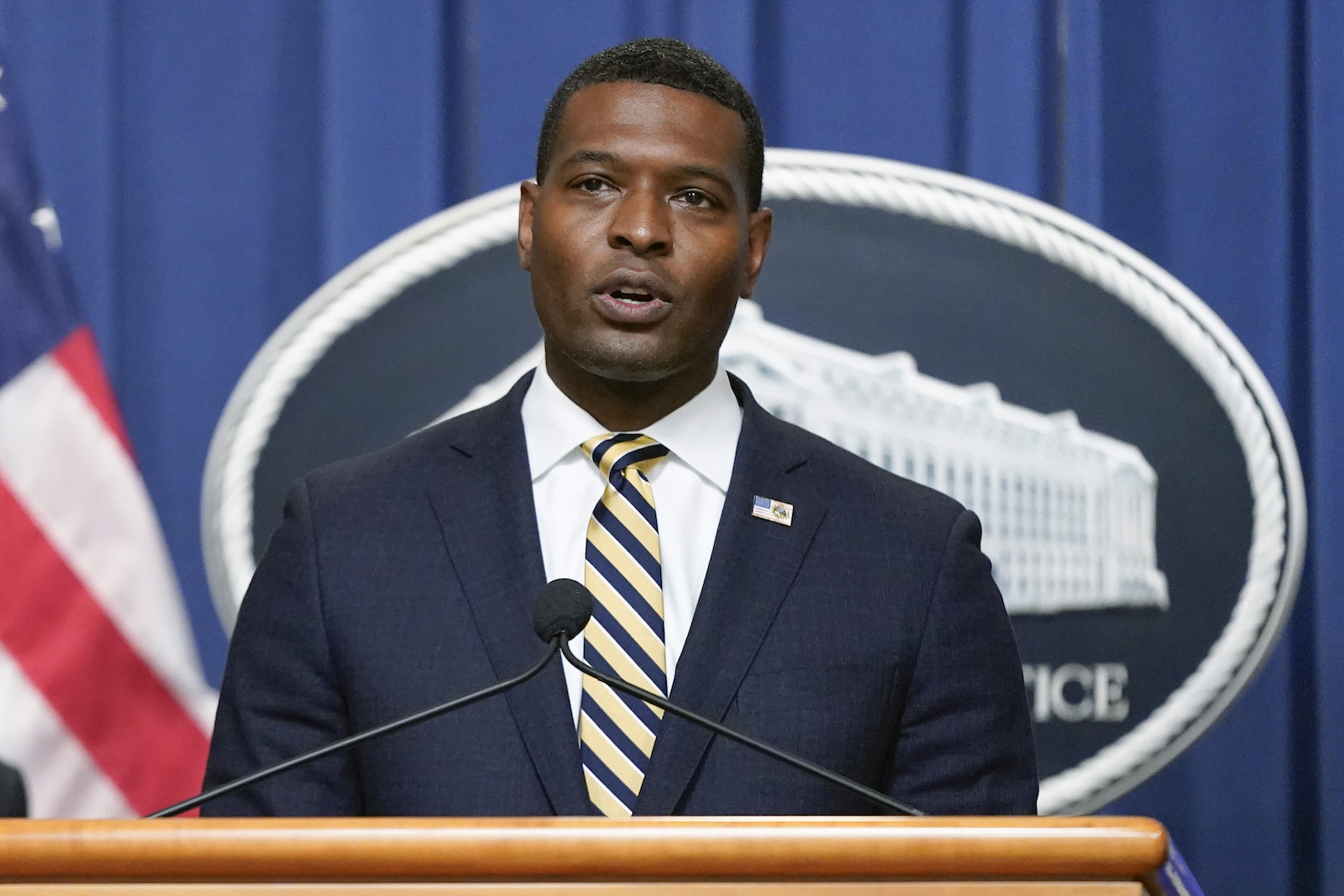

“After three rounds of investments, EPA is delivering on President Biden’s full promise to invest in cleaning up America’s most contaminated Superfund sites,” said Janet McCabe, deputy EPA administrator, in the press release. “This final round of Bipartisan Infrastructure Law funding has made it possible for EPA to initiate clean ups at every single Superfund site where construction work is ready to begin.”

The massive undertaking is part of the Biden administration’s Investing in America agenda and funded by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. The final wave will include 25 new cleanup projects and the continuation of 85 that are already underway.

The Superfund program — originally created with passage of the Comprehensive Environmental Response Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) by Congress in 1980 — assists with the repurposing of land like warehouses and parks that have been polluted by heavy industry so that it can be used for new economic development, reported Reuters.

“The law gave EPA the authority and funds to hold polluters accountable for cleaning up the most contaminated sites across the country. When no viable responsible party is found or cannot afford the cleanup, EPA steps in to address risks to human health and the environment using funds appropriated by Congress, like the funding provided by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law,” the press release said.

According to McCabe, more than a quarter of Black and Hispanic people in the U.S. live within three miles from a Superfund site, three quarters of which are located in historically underserved communities.

“Every American deserves clean air to breathe and access to clean land and water, no matter their zip code,” said Delaware Senator Tom Carper in the press release.

Across the country, thousands of sites have been contaminated by the neglectful dumping, improper management or open abandonment of hazardous waste. The sites can be polluted by toxic chemicals from processing plants, manufacturing facilities, mining and landfills, and can put the health and well-being of urban and rural communities at risk.

“This funding will help improve people’s lives, especially those who have long been on the front lines of pollution,” McCabe told reporters, as Reuters reported.

The projects are part of the president’s Justice40 Initiative, which has a goal of 40 percent of certain federal investments going to disadvantaged communities that have been overburdened by pollution and marginalized by underinvestment.

Frank Pallone, U.S. Representative from New Jersey, told reporters that the funding will complement another $23 billion for Superfund to come from “polluters pay” taxes reinstated by the Inflation Reduction Act, reported Reuters.

“Reinstating that Superfund tax is really only about basic fairness that corporate polluters, not taxpayers, should have to pay to clean up the messes that they created,” Pallone said.

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law funding will help with the cleanup of sites from New Jersey — which has the most Superfund sites of any state — to Oregon.

“Superfund sites threaten public and environmental health across the country, but with today’s announcement, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law is continuing to deliver on the promise we made to clean up backlogged sites and give our communities the peace of mind they deserve,” Pallone said in the press release. “For dozens of communities, today’s funding is a welcome assurance that help is on the way.”

The post U.S. EPA Announces $1 Billion Toward Cleanup of Superfund Hazardous Waste Sites appeared first on EcoWatch.

When combined with green spaces, solar panels can provide more benefits than generating clean energy.

According to a new study, led by Lancaster University scientists in collaboration with the University of Reading, well-managed solar parks that feature solar panels and vegetation could boost pollinator populations and biodiversity. The researchers published their findings in the journal Ecological Solutions and Evidence.

The team used field observations and landcover data to track the impact that solar park plants have on pollinators. They surveyed 15 solar park sites around England, noting plant resources and the surrounding landscape characteristics, such as any wooded areas nearby or whether surrounding landscapes were well-connected or disconnected.

Overall, they observed 1,397 pollinators across at least 30 species. Butterflies were the most-observed pollinator, making up 64% of all observed pollinators. Butterflies were also found at all 15 sites, the only type of pollinator present at all the solar parks in the study.

The researchers spotted 171 hoverflies (12% of the total), 161 bumblebees (12%), 157 moths (11%) and just nine honeybees, making up less than 1% of the observed pollinator species at the solar parks. They did not record any observations of solitary bees.

The study authors noted that the solar parks tended to support generalist pollinators, which visit a variety of plant species, over specialist pollinators, which rely on few or only one plant species. Still, they did find a diverse range of generalist pollinators at solar parks with various flowering plants.

Solar parks with more diversity in on-site flowering plants were linked to a wider range of pollinator species and a greater abundance of pollinators. According to the study, floral species diversity was the most influential variable on pollinators in the study.

In general, researchers observed the most abundance and highest species diversity of pollinators in July. But aside from plant diversity and month, another factor had a significant impact on many types of pollinators: the surrounding landscape.

According to the study, solar parks were especially beneficial to pollinators in areas with disconnected landscapes. The authors noted that this could be because areas with well-connected landscapes rich in hedgerows and trees could be more attractive to pollinators because they offer a wider range of resources.

“We’ve shown that through management decisions such as planting a variety of flowering plants, solar parks can support insect pollinators and also those communities can be relatively diverse and abundant — particularly in those landscapes where there are few hedgerows and wildflowers for pollinators to depend on,” Hollie Blaydes, lead author of the study, said in a statement.

This means solar parks could not only be sites for generating energy, but they could double as pollinator habitats in areas that lack natural resources to support pollinators.

The post Well-Managed Solar Parks Could Boost Pollinators in UK, Study Says appeared first on EcoWatch.

Technology and consumer electronics products have transformed life in just two generations but they’ve come…

The post Earth911 Podcast: TCO Certified’s Andreas Nobell on Choosing Sustainable Technology appeared first on Earth911.

This story was developed with the support of Journalismfund.eu.

In August 2020, Maria do Espirito Santo was returning from her family’s field in the savanna of northeast Brazil when she saw smoke billowing from her thatched hut.

Do Espirito Santo raced back to find that her home and those of her neighbors had been burnt to the ground by a group of armed men, some of them local police. They felled fruit trees, ripped up crops with tractors, and forced the small community of Bom Acerto from the lands where they had grown cassava, corn, and beans for generations. Afterward the families found out a businessman from Tocantins, the state she lives in, had laid claim to 10,872 acres of public land abutting 9,884 acres of land he had purchased, which includes the land that her family has been living on for generations. They suspect that he hired the men and bribed the police to come and terrorize the families so that they would leave.

“When we arrived, we found several dozen people, mainly women and children, huddling under the one remaining structure that cast any shade,” said Maciana Veira, president of the Sindicato dos Produtores Rurais de Balsas, the local rural workers association. Veira, in her decades of work for the association, has more accounts of land being stolen from rural communities than she can count.

Brazil possesses vast tracts of lands which exist in the public domain. Traditional peoples, small-scale farmers, quilombolas, and other homesteaders have the legal right to lay claim to these lands, but in rural Brazil, many communities like Bom Acerto still lack formal deeds. Those seeking to claim that land — often business owners or corporations — reportedly hire armed men to intimidate and run off residents. They then clear the land of trees or native vegetation, either seeding pasture for cows or preparing it to grow crops like soy, cotton, or corn. Eventually, they gain formal ownership through legal maneuvers or by forging land titles, sometimes by leaving falsified titles in a box with crickets, whose excreta makes the papers seem older than they are. It’s such a common practice that it’s picked up its own noun: grilagem, derived from the Portuguese for cricket, grilo.

Land grabbing is not a new phenomenon in Brazil, but it’s especially rampant in the 337 municipalities in the northern Cerrado that make up an area known as Matopiba (a portmanteau of the states Maranhao, Tocantins, Piaui, and Bahia.) The Cerrado, the world’s most biodiverse savanna, stretches 1.2 million square miles up the spine of Brazil, covering a fifth of the country. Squished between the Amazon rainforest on one side and the Atlantic rainforest on the other, it has been dubbed “the underground forest” because so much of its biomass is found in the long, thick roots that funnel water down into aquifers and store impressive amounts of carbon. Deforestation and land use change is Brazil’s single largest source of greenhouse gas emissions, so conserving the Cerrado, and its role as a carbon sink, is crucial for Brazil to meet its Paris Agreement goals. Much of the biome’s last remaining tracks of native Cerrado vegetation are in Matopiba, the country’s last agricultural frontier.

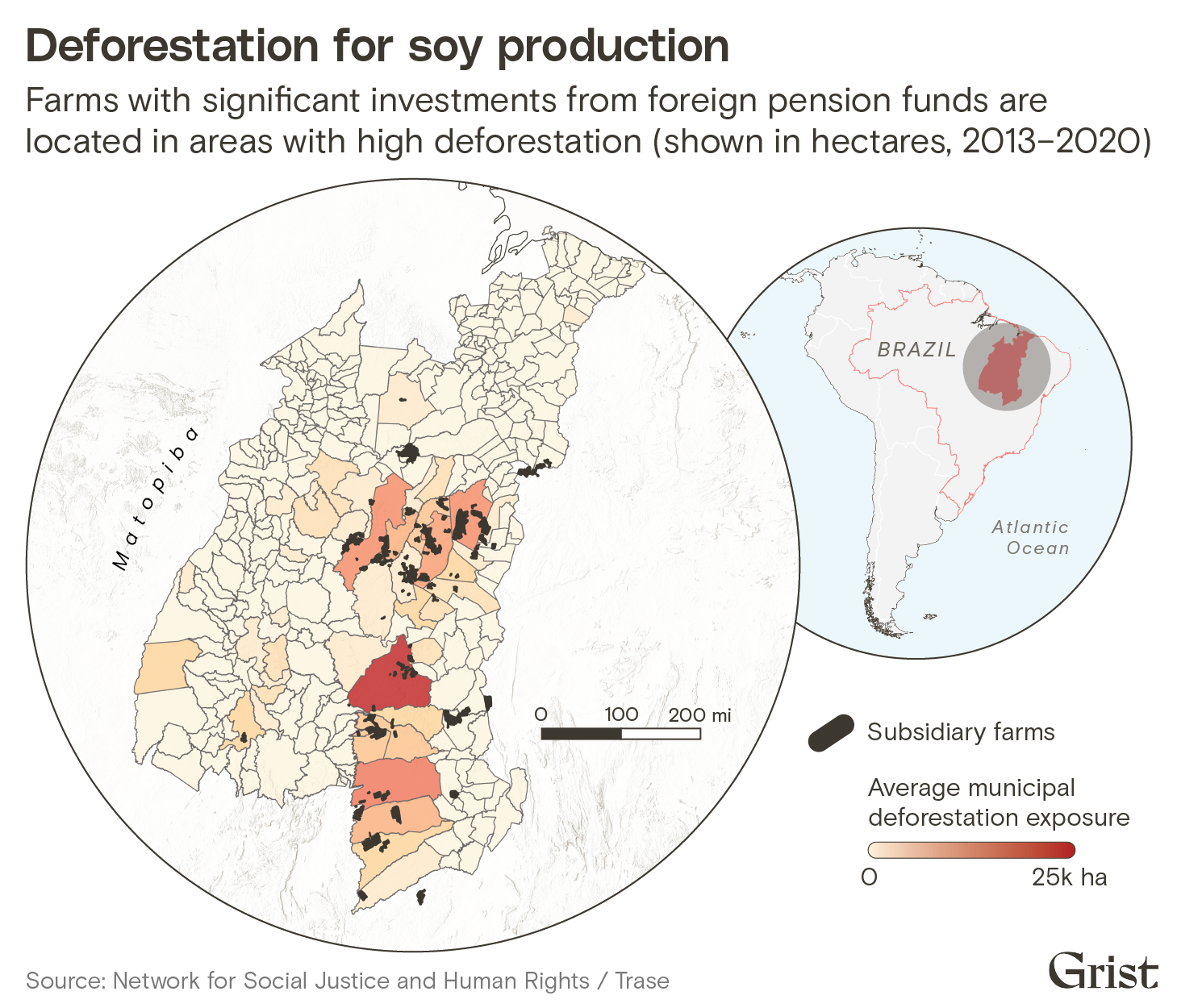

In Matopiba, some 1.7 million acres of native vegetation were ripped up and turned into soy plantations between 2013 and 2021, helping to turn Brazil into the world’s largest producer and exporter of soybeans. Most of the beans are used to fatten livestock in Europe and China, the two biggest buyers of Brazil’s crop. The usual narrative is that the destruction of the Cerrado is closely linked to the growing demand for meat and dairy. The full story, however, is more tangled and wider in scope: Behind this rapid and widespread transformation are some of the world’s largest investment funds that have put billions into buying farmland in the Cerrado, including pension funds in Sweden and Germany, Harvard University’s endowment, and the Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association, better known as TIAA, the $1.2 trillion pension fund for 5 million people across the United States.

Thanks in part to its investments in Brazilian farmland, TIAA has become one of the largest farmland investors in the world. Through its wholly owned subsidiary, Nuveen Natural Capital, the fund has accumulated some 3 million acres across 10 countries. It owns stakes in water-hungry almond and pistachio orchards in drought-stricken California, Macadamia nut farms and row crops in Australia, and vast swaths around the Mississippi Delta. But its investments in Brazil, where it manages 1 million acres, are some of its most controversial holdings.

Around the time of the financial crisis in 2008, TIAA and other investment funds started buying up farmland in Brazil, eventually honing in on the northern Cerrado, specifically Matopiba, where environmental protections are thin and land ownership is often in disputed. According to environmental organizations, academic researchers, satellite images, and media reports, many of the farms TIAA acquired are connected to land grabbing and deforestation. TIAA has regularly denied any knowledge of these practices, but emails and other leaked documents obtained from a data breach last year reportedly showed that as far back as 2010, TIAA was aware that some of the land it purchased was bought from people publicly accused of stealing it — groups like those that destroyed do Espirito Santo’s village of Bom Acerto. Despite an almost decades-long campaign by the Brazilian nonprofit The Network for Social Justice and Human Rights, along with environmental advocacy groups like ActionAid and Friends of the Earth, to get TIAA and other foreign funds to divest from their Brazilian landholdings, TIAA continues to raise money to invest in the region.

Connecting specific farms to specific investment funds is a complicated task, said Lucas Seghezzo, a professor of environmental sociology at the National University of Salta, Argentina, who studies large-scale land acquisitions. Investment funds often keep their assets private when they aren’t stocks and bonds, and following the money can lead to a maze of shell companies and chains of subsidiaries. Researchers wind up stuck in dead ends. Deforestation and land clearing is a complex process, and not every instance is directly connected to pension funds or investors. But experts have traced the massive influx of foreign capital in Matopiba to skyrocketing land prices in the region, which, in turn, has fueled land grabbing, deforestation, and violent conflicts, all with devastating consequences for local communities and the land itself.

“There’s a lot of evidence that investors who buy land in Latin America, for instance, but also in Southeast Asia, are responsible for deforestation — directly or indirectly,” said Seghezzo, who is also a scientific advisor to the Land Matrix Initiative, an independent monitoring initiative. “There is a clear correlation between land acquisitions and deforestation, especially those for agriculture.”

Bom Acerto is a two-hour drive from Balsas, an agricultural town in the heart of Matopiba. The route there is largely unpaved, passing over hills and through miles of scraggly shrubs and waving golden grass. The road dips occasionally from flat stretches of savanna into lush forests wedged into tiny riverine valleys. Far less known than the Amazon rainforest that borders the savanna to the north and west, the Cerrado is Brazil’s second-largest biome, covering an area larger than Germany, France, England, Italy, and Spain combined. It’s one of the oldest and richest ecosystems on Earth, with 5 percent of the planet’s biodiversity.

Much of the Cerrado has been plowed under for agriculture, especially in the southern and central parts of the savanna, which are closer to large urban centers like Sao Paulo and Brasilia, the country’s capital. Some of the last remaining swaths of intact Cerrado vegetation remain in the north, around places like Bom Acerto, which until the beginning of the 20th century had been largely occupied by peasant, Afro-Brazilian, and Indigenous communities.

Fabio Pitta has been studying the expansion of agriculture in the Cerrado since he was a university student researching sugarcane companies in the mid-2000s. Rising oil and gas prices and fossil fuel companies’ desire to appear “green” had stoked investments in sugarcane, which could be turned into ethanol when gas prices were high and used as sugar when they were low. The size of farms in the region was steadily growing, as were the number of laborers literally working themselves to death. Pitta set out to study this dynamic, focusing on Cosan, Brazil’s largest producer of sugarcane. He was puzzled to find that the company had started buying up large tracts of land in the Cerrado around 2008, thousands of miles from its home base near Sao Paulo in the southern Cerrado, through an investment arm it created called Radar Propriedades Agrícolas, or simply Radar.

More puzzling still was the identity of Radar’s second-largest shareholder, an investment fund run by what was then known as TIAA-CREF, the pension giant in New York City that manages retirement funds for millions of American teachers and professors.

Pitta was witnessing the convergence of two global crises. The U.S. financial crisis that started in 2007 sent big investors scrambling to find assets that weren’t tied to American real estate. Farmland, once considered a backwater and risky investment, gained overnight appeal. The surge in prices of basic staples that had started in 2005 had, by 2008, led to a fully fledged global food crisis. The commodities that could be grown on farmland suddenly became much more valuable, too. “Buying farmland was like buying gold with yield,” said Roman Herre, an agricultural expert at FIAN Germany, a human rights organization that advocates for the right to food. And global investors, Herre said, rushed to buy up whatever farmland they could.

More than 100 new investment funds specializing in food and agriculture were created between 2005 and 2008, and agricultural investment magazines and conferences ballooned. Famous investors like George Soros wanted in. Whereas in 2008, the annual expansion of farmland hovered around 9.9 million acres a year, by the middle of 2009, around 138 million acres worth of large-scale farmland deals had been announced, many of them larger than 500,000 acres, or two and a half times the size of New York City. It was dubbed “a new global land rush.”

“In the beginning, it was really more like a Wild West story,” Herre said. And one of the biggest players was TIAA, which went from having virtually no farmland in 2007 to holding just shy of 2 million acres worldwide within a decade.

But it wasn’t just teachers in the United States whose savings were providing the capital for the land rush. Dutch, Canadian, and Swedish public employees, along with German physicians, were also funding it. In 2012, TIAA launched its first international farmland fund called TIAA-CREF Global Agriculture LLC with $2 billion primarily from pension funds to invest in farmland, primarily in Brazil, Australia, and the U.S. The roster included Swedish AP2, then one of the largest pension funds in northern Europe, Germany’s Ärzteversorgung Westfalen-Lippe, a pension fund for physicians, and the Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec, a public and private pension fund manager with around $176 billion in assets at the time. TIAA launched a second fund in 2015, the $3 billion TIAA-CREF Global Agriculture II LLC.

Figuring out exactly where these investments were located was difficult. Pension funds and other private investors don’t have to disclose precisely where their farmland holdings are, and investors often use complex business structures to buy farmland — particularly in places like Brazil, where foreign land ownership is legally restricted. Much of the data on TIAA’s investments comes from organizations like The Network for Social Justice and Human Rights, which Pitta now works for, that have traced the money through a messy web of subsidiaries and land acquisition companies, of which TIAA owns more than seven in Brazil, according to TIAA’s 2021 statements.

In 2016, the investment data company Preqin estimated that since 2006, more than 100 unlisted funds had raised approximately $22 billion in capital globally to invest in agriculture and farmland. TIAA’s investments, by far the biggest of any investor, made up almost a quarter of those.

“TIAA is really the vanguard of pension funds making this type of investment,” said Gustavo Oliveira, an assistant professor of geography at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, who has been studying foreign investments in Brazil. “The important role that TIAA plays is not just on its own, because it’s got deep pockets and it invests in a lot of land. It is that once TIAA has ventured deep, it then becomes possible for smaller pension funds and other investors to follow in its wake.”

The northern Cerrado is crisscrossed by a handful of paved highways, lined on all sides by soybeans, that connect large agricultural hubs in Matopiba. In the rainy season, it’s a sea of bright green as far as the eye can see. Trucks thunder down the highways to and from large grain silos, many of them owned by international agricultural giants such as Bunge and Cargill which, alongside a few other companies, control more than half of the soy trade in Brazil. In the dry season, the soil lies bare and dusty, large piles of stark white lime piled up to one side, applied liberally to coax the otherwise nutrient-poor, acidic soil into producing what is now one of Brazil’s most lucrative exports. Over the last two decades, soybean production in Brazil has more than quadrupled.

The farms are so large that their office complexes lie miles away from the highway, often on the iconic flat-top mountains called chapadas, ancient sandstone and quartzite formations formed tens of millions of years ago. While the rusty signs on the farms are largely in Portuguese, some of the owners are global. Between 2008 and 2020, Harvard Management Company, which manages Harvard University’s endowment fund, amassed more than 40 rural properties covering approximately 1 million acres, an area twice the size of all the farmland in the school’s home state of Massachusetts. BrasilAgro, whose shareholders include the Utah Retirement Systems, the Los Angeles City Employees Retirement System, and the Public School and Education Employee Retirement Systems of Missouri, owns a total of 741,000 acres in Matopiba. SLC Agrícola, one of the country’s largest soy producers and TIAA’s largest farm operator, and its sister organization SLC Landco, a joint venture with the British private equity fund Valiance, collectively bought up more than 450,000 acres of farms in Matopiba between 2011 and 2017.

While soybean farming has been expanding in the Cerrado for several decades, the relatively recent spread of soy into Matopiba, which has attracted the bulk of foreign farmland investment, stands out. “Matopiba is a relatively small portion of the Cerrado overall, but it is without a doubt the main expansion frontier for soy in the region,” said Lisa Rausch, a scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who for the last two decades has studied how agricultural production leads to forest loss in Brazil.

Elsewhere in the Cerrado, soybeans tend to be grown on already converted land, often pasture. But in Matopiba, the vast majority of new farmland created since the turn of the century has been from previously intact Cerrado vegetation. According to Trase, a group that tracks global supply chains, three-quarters of all the deforestation from soybean production in the entire Cerrado from 2005 to 2016 happened in Matopiba alone. “One of the main features of soybean expansion in Matopiba has been its association with the clearing of native vegetation,” Rausch said.

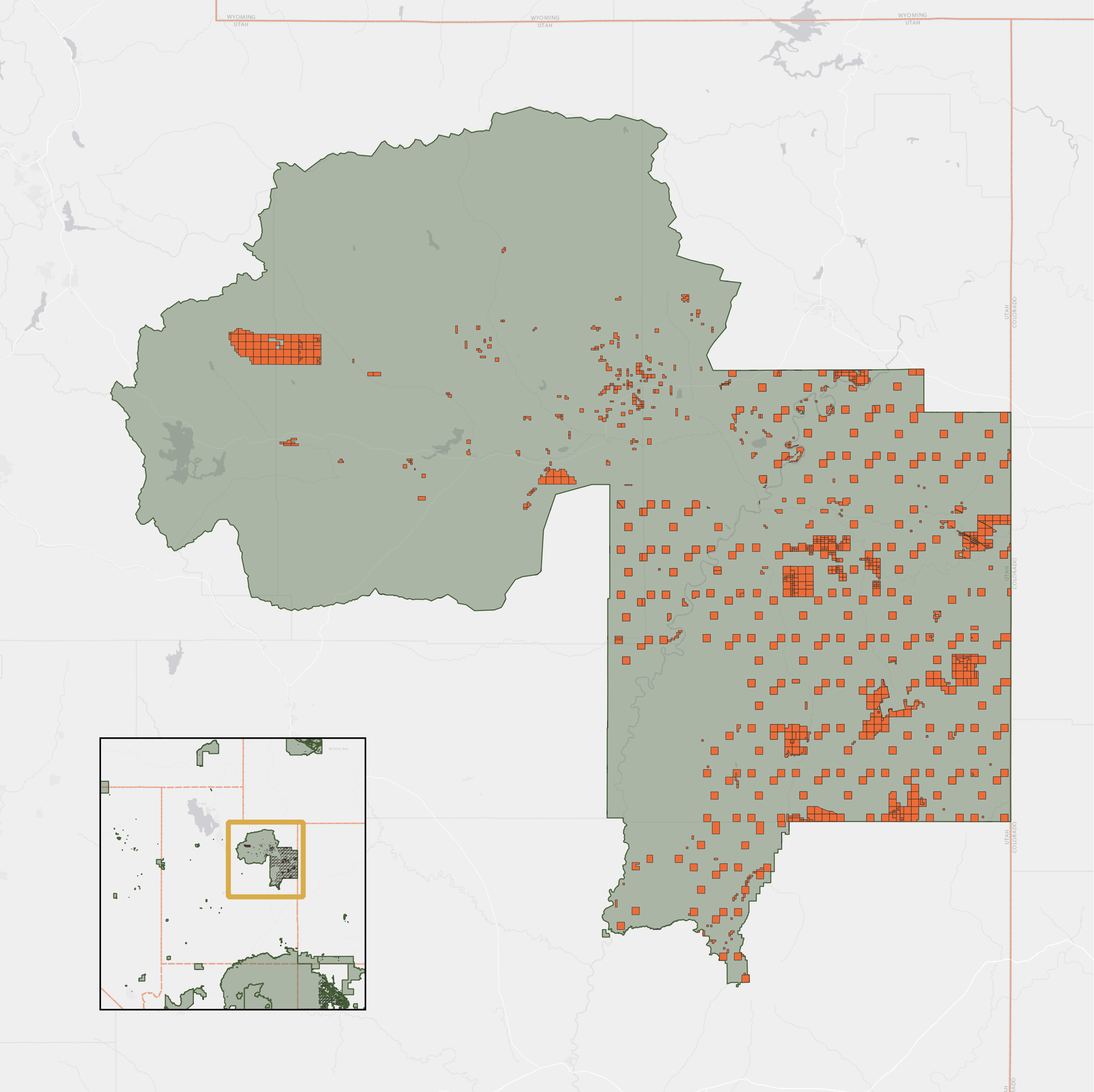

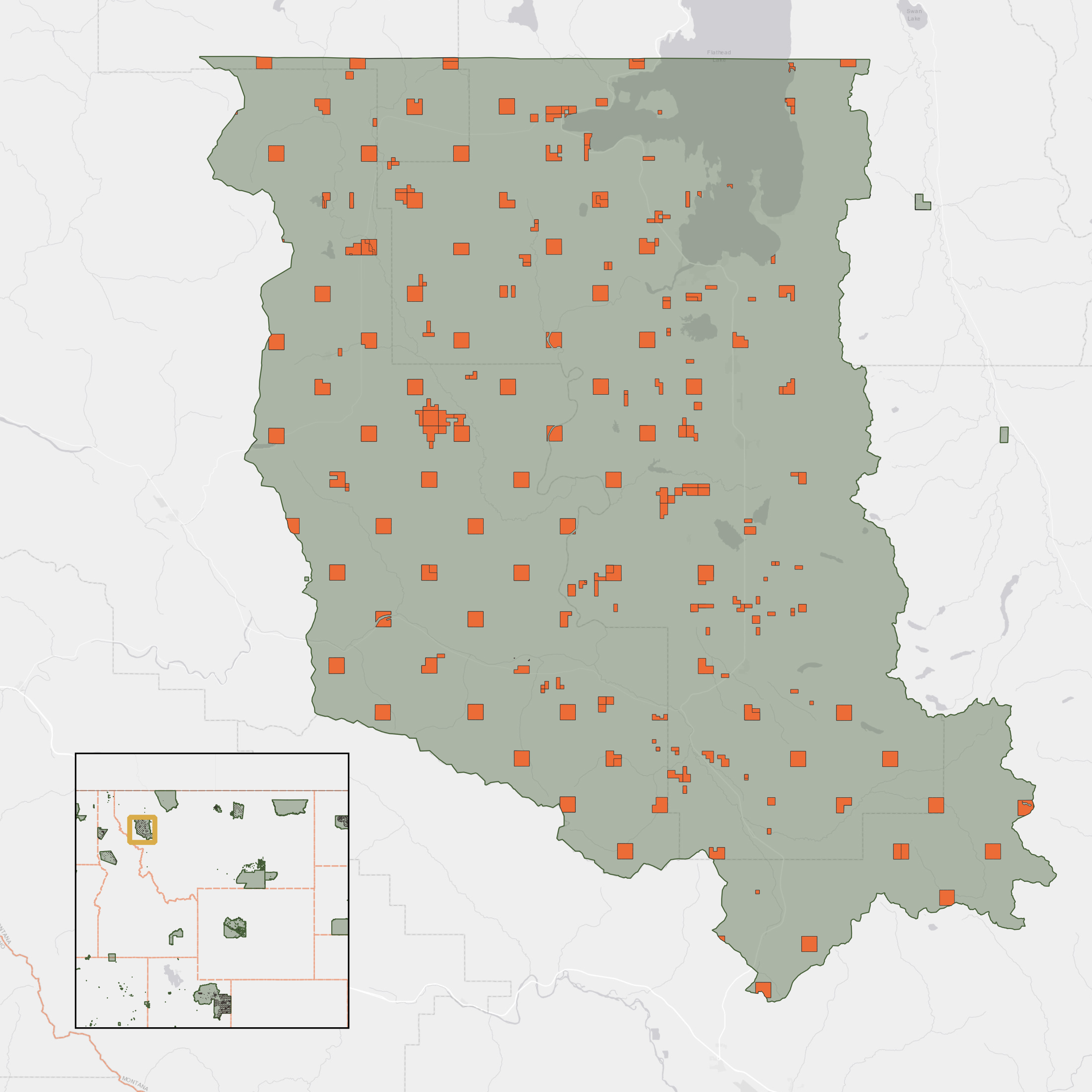

Based on data obtained from the Network for Social Justice and Human Rights and Trase, Grist mapped the municipalities of farms that had significant investments from foreign pensions funds with information on which municipalities had the highest deforestation risk from soy farming. The results revealed that farms with significant foreign investment owned thousands to tens of thousands of acres in nine of the 10 municipalities that have experienced the most deforestation from soy from 2008 to 2020.

The loss of habitat threatens the region’s biodiversity, and consequently, the livelihoods of locals, many of whom depend on the forests and shrublands of the Cerrado for food and medicine. Alongside deforestation and foreign farmland investment, violent land conflicts in the region have also ballooned. Matopiba saw an overall 56 percent increase in reported land conflicts between 2012 and 2016, in contrast to a national increase of 21 percent. According to the Pastoral Land Commission, an organization affiliated with the Catholic Church that tracks conflicts in Brazil’s countryside, Bahia and Maranhao — both in Matopiba — ranked first and second among the states with the highest number of conflicts in 2022.

To be sure, some funds have dropped their investments in companies that deal in soy in the Brazilian Cerrado, some citing deforestation risk, others based on what they claim are financial reasons. The Norwegian Government Pension Fund and the Danish insurer Danica Pension divested their shares from SLC Agricola in 2017 and 2021, respectively. And last year, Germany’s pension fund for physicians in Westphalia-Lippe divested its shares from TIAA’s Global Agriculture Funds. But others have jumped in: In 2022, the Board of the Los Angeles County Employees Retirement Association committed around $500 million to TIAA-CREF Global Agriculture Funds, which encompasses its Brazilian farms.

The rapid expansion of large farms, funded by an influx of foreign capital, has reshaped the Cerrado’s landscape. The long, thick roots of vegetation store billions of metric tons of carbon, and have long funneled the region’s rainwater into aquifers. Two-thirds of Brazil’s rivers originate here, and nine out of 10 Brazilians use electricity generated by water originating in the Cerrado, according to the World Wildlife Fund. Now, so many trees and shrubs have been ripped out for soy fields, cattle, and sugarcane plantations that nearly half of the biome is cropland or pasture. Scientists predict that if agricultural expansion continues unabated, the biome could collapse by 2030, threatening the region’s drinking water as well as the thousands of unique species native to the world’s most biodiverse tropical savanna.

The soya boom is far from over. Brazil is expected to plant roughly 30 million more acres of soy between 2021 and 2050, according to one study. Of that, 27 million acres are destined for the Cerrado, and 86 percent of that is projected to be planted in Matopiba. But this is already coming at a cost. “The loss of native vegetation in the Cerrado has very serious consequences environmentally,” Rausch said. That loss has disrupted the region’s water cycle and has increased the frequency of extremely hot days in places like Matopiba, leading to more severe droughts. Climate change is likely to make all these problems worse.

TIAA has previously said it invests responsibly and always carries out thorough due diligence on land purchases. But last year, a hacker group obtained 100 gigabytes of files from Cosan, Brazil’s sugarcane giant, through a ransomware attack, a trove that included sales documents, land holding records, legal papers, and emails, which were then handed over to Distributed Denial of Secrets, an activist group. They reportedly revealed that both Cosan and TIAA ignored red flags when buying Brazilian farms — even purchasing land from people who had already been publicly accused of stealing it.

Grist reached out to TIAA and its subsidiary Nuveen to respond to the information uncovered in the data breach and asked how the pension fund incorporates sustainability into its investment decisions. A spokesperson replied that TIAA and Nuveen evaluate the impact of their investments on local communities, make sure that the land they acquire and hold meets all government requirements for forest and natural habitat protection, and also ensure that their investments comply with local rules and regulations.

“Any suggestion that TIAA has engaged in improper business practices is without merit,” the spokesperson wrote. “In every country in which we operate, including Brazil, we follow the requirements of all laws and adhere to strong ethical guidelines in our investments. And we expect the government to investigate and prosecute instances of land-grabbing wherever it occurs.”

News of TIAA’s farmland holdings in Brazil first gained widespread attention in 2015 when a smattering of media reports began to lay out the extent of TIAA’s investments in the Cerrado. But it was a report in 2018 that detailed the scope and scale of Harvard endowment’s extensive landholdings in Brazil, written by the Network for Human Rights and Social Justice and the international nonprofit GRAIN, that gave the issue traction in the United States. The news spurred the growing fossil fuel divestment movement at Harvard to include land grabbing in its platform, forming the “Stop Harvard Land Grabs” campaign. Brazilian authorities were also starting to take notice, scrutinizing companies backed by Harvard’s endowment and TIAA.

In 2020, a small activist group called TIAA Divest tapped Caroline Levine, an English professor at Cornell University, to help lead a campaign to urge TIAA to get rid of its investments in fossil fuels and other environmentally destructive industries. Earlier that year, Levine had successfully helped win the campaign to get Cornell to divest its own endowment from fossil fuels, and she was riled up by what she saw as the blatant disregard for the environment and human rights that accompanied many of the investment decisions universities were making.

“I had this idea that financiers were sort of unaware of what was happening, that there’s a kind of distance between the investment and what’s going on on the ground,” Levine said. “But the more I looked at it, the more it seemed like, ‘No, there’s a lot of conscious bad action happening.’”

Levine and a dozen other professors started researching TIAA’s investments, but were taken aback by the sheer number of shell companies and the opaque web of financial flows. “I’m a researcher, but this really wasn’t my ballpark,” she said. They brought on Tom Sanzillo, a former New York state comptroller then working with the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, who talked them through the financial hurdles. After two years of gathering evidence, they filed an 87-page complaint in October 2022 to the United Nations-sponsored Principles for Responsible Investment against TIAA and its subsidiary, Nuveen. Nearly 300 academics, researchers, and TIAA account holders signed on, including the climate scientist Michael Mann, the American academic Judith Butler, and the writer and activist Bill McKibben.

“TIAA/Nuveen’s climate commitments are contradicted by its substantial investments in fossil fuels and commodities linked to deforestation, which undermine the climate objectives established in the Paris Agreement,” the complaint states. “TIAA/Nuveen’s ongoing investments in coal, oil, and gas, as well as land-based investments linked to deforestation and illegality, are financially, morally, and socially irresponsible.”

TIAA was one of the founding signatories of Principles for Responsible Investment, or PRI, in 2006, which aimed to help investors make their funds more sustainable. The complaint argued that the $78 billion worth of investments in fossil fuels, as well as various environmental and human rights abuses connected to their large farm holdings in the Brazilian Cerrado, violated PRI’s principles, as well as TIAA’s own climate pledges. It charged that TIAA was misleading investors by advertising its funds as climate-friendly, making the case that many of its products marketed as being aligned with ESG principles — shorthand for environmentally and socially responsible — allegedly had higher exposure than non-ESG funds to fossil fuels and deforestation, the top two sources of greenhouse gas emissions in the world.

PRI signatories commit to six principles, including incorporating ESG matters into decision-making. While PRI has a serious violations policy, it is only sparingly applied, Levine said. In 2021, the Save the Dawson project in Australia filed a complaint to PRI about Liberty Mutual’s financing of a coal mine, which resulted in the global insurer canceling their financing. In October 2022, PRI said that it had reviewed Nuveen’s response to the allegations and “decided that the allegations do not constitute a breach of the policy. As such, there is no reason to change Nuveen’s status as a PRI signatory,” they wrote in an email response to Levine.

“We knew it was a long shot,” Levine said. Still, she considered the result disappointing.

University students, professors, and pension holders aren’t the only ones attempting to highlight the connection between foreign investment funds, deforestation, and land grabbing. Traditional communities and peasant farmers in Matopiba have protested in front of government agencies and blocked roads to bring attention to the problem. Last June, a delegation of leaders from several rural communities in Piaui handed a letter to government authorities asking for the state to protect them from ongoing violence and violations of their rights.

“Human rights violations in Piaui caused by land grabbing, deforestation, fumigation with toxic agrochemicals and other pollutants, as well as physical and psychological violence against rural communities, have been widely documented and brought to the attention of state and federal authorities,” the letter said. “The perpetrators of the violence are usually individuals linked to local land grabbers and/or agribusinesses, but research has shown that international investors play a key role in encouraging human rights violations and environmental crimes in the region.”

Around 10 miles from Bom Acerto, piles of native shrubs and vegetation cook in the punishing sun, their long, thick roots a contrast to the bright blue sky and the flat-topped mountains in the distance. For generations, the tops of these mountains were common areas used by peasants and Afro-descendent communities to forage for food, firewood, and medicines. People preferred to live in the more lush valleys, where crystalline rivers flowed. Nowadays, many of these rivers are polluted with agricultural runoff, and plantation owners keep ripping out more native vegetation. Just over the border from Bom Acerto, in Piaui, 5,000 acres of land was cleared in 2021 from a large farm, called Kajubar. In all likelihood, Pitta and other researchers predict, it will be sold to the highest bidder.

Though not all the deforestation in Matopiba can be directly linked to foreign investors, researchers agree that the scale and speed of destruction would not be possible without the massive influx of foreign capital. “Even if they sold all the enterprises, they profited from them a lot, and the impacts are still there,” Pitta said. Last year, the Stop Harvard Land Grabs campaign published a petition demanding that Harvard “stop investing in new farmland, return the lands already acquired to affected communities, and pay reparations for the undeniable harm of Harvard’s global land business.”

Meanwhile, forests continue to be torn down in the Cerrado at a fast clip. Between July 2022 and August 2023, deforestation in the region rose almost 17 percent, eating up more than 1.5 million acres of Cerrado vegetation, an area almost twice as large as Yosemite National Park. Around three-quarters of that was in Matopiba. According to the Pastoral Land Commission, more than 20,000 families in the four states were involved in conflicts over land in 2022, a record number.

In Bom Acerto, all that remains of the former settlement are piles of ashes and empty trails. The community has tried to take the businessman who is claiming he owns their land to court, but the case is stalled. Despite the uncertainty, the community has begun to rebuild some of the stalls for animals, and replant the fields with cassava, beans, and rice. Most of the trails end at the edge of the dry forest, where native Cerrado vegetation still extends for acres and acres into the horizon.

Last January, do Espírito Santo stood on the site of her old house and looked toward the village that she and her old neighbors are slowly piecing back together. “My dream is to stay here,” she said. “My dream is that we have the right to stay here, that we have the right to have our land and our home.”

At the end of August, four men in an unmarked pickup truck invaded Bom Acerto and set fire to a family’s house. Now, residents report that a drone constantly flies overhead. Most of the native Cerrado is still visible out beyond their fields, but for how long, do Espírito Santo doesn’t know.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Who’s behind the destruction of Brazil’s Cerrado? on Feb 28, 2024.

This story was published in partnership with High Country News.

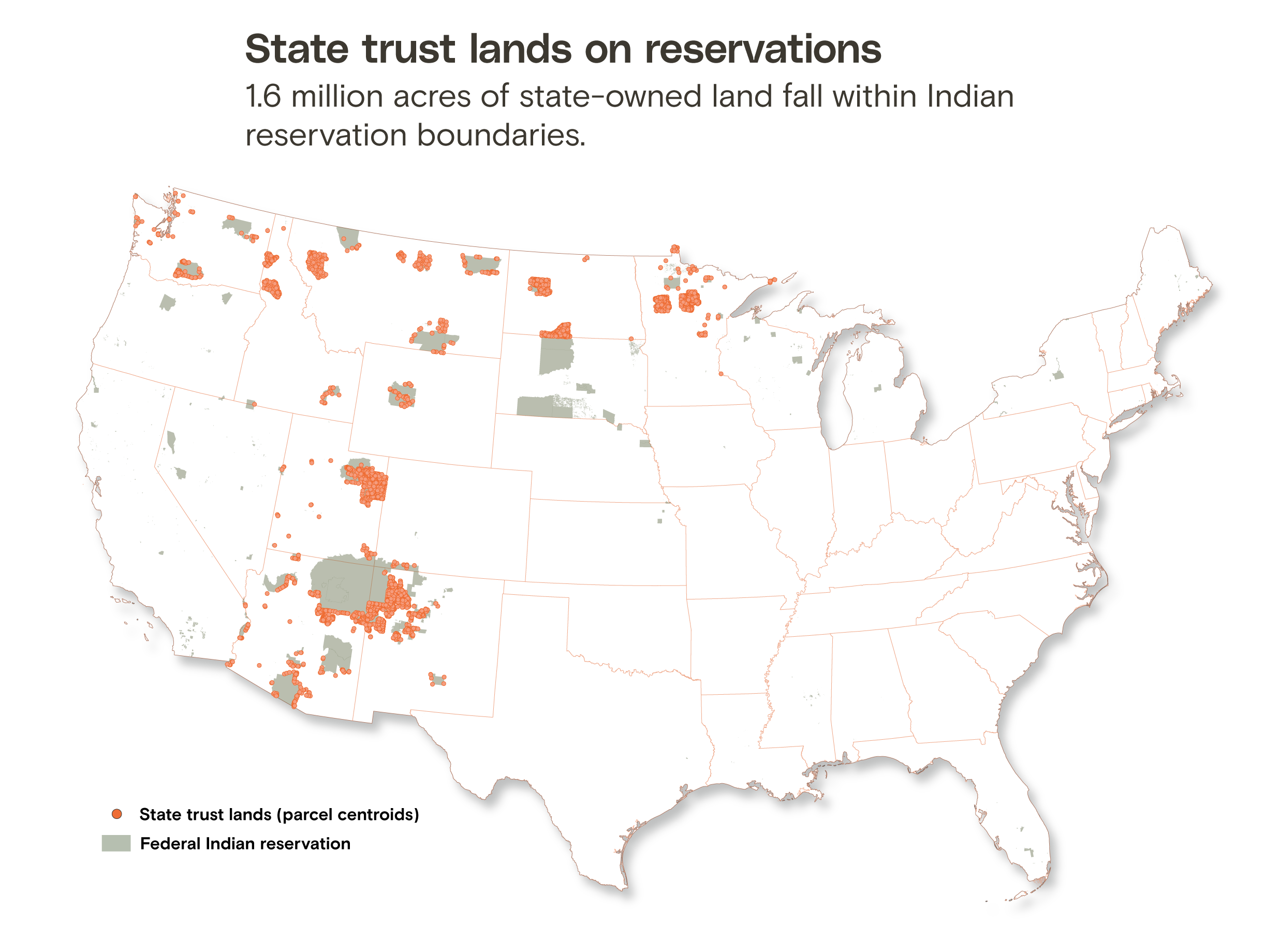

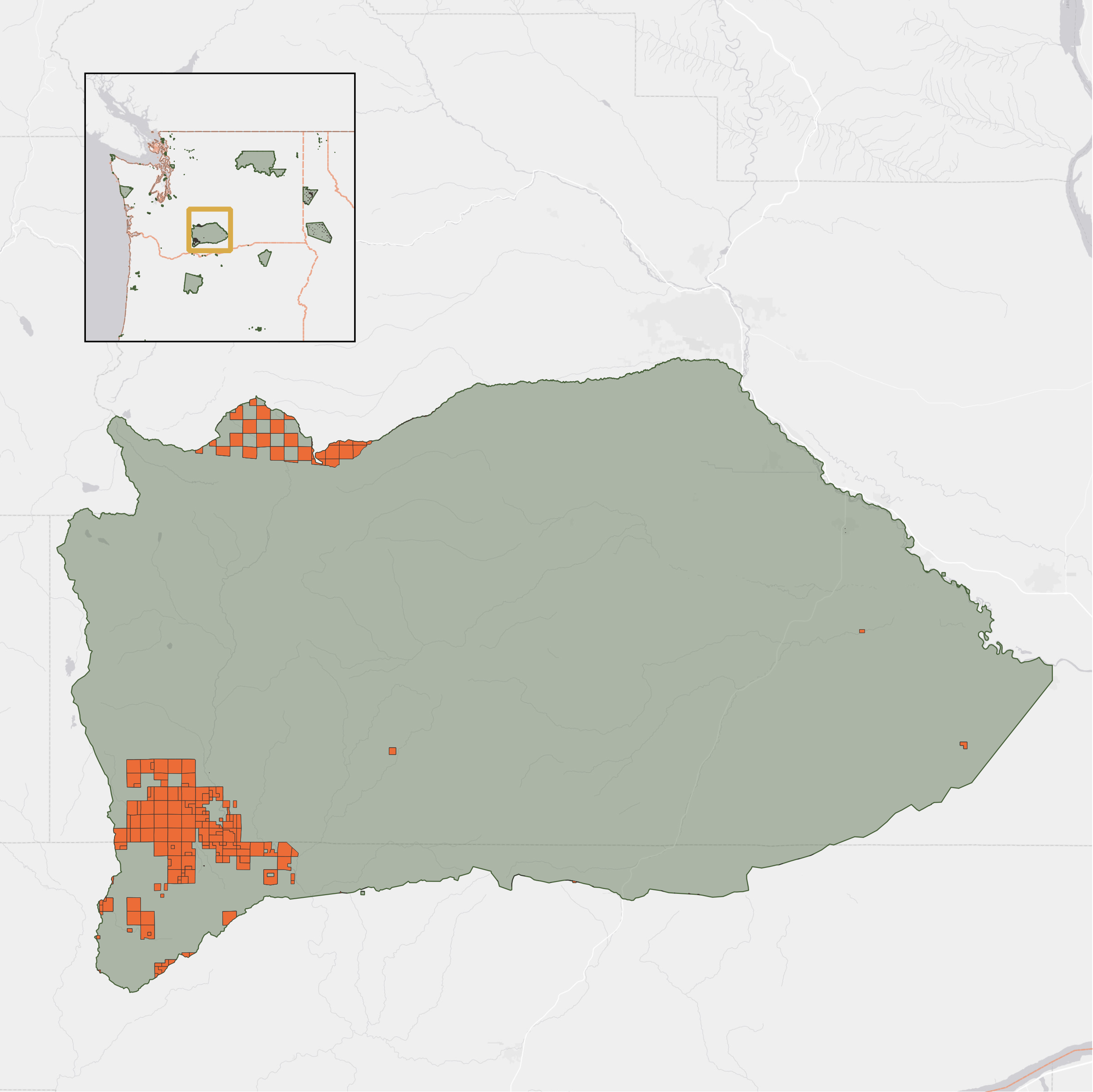

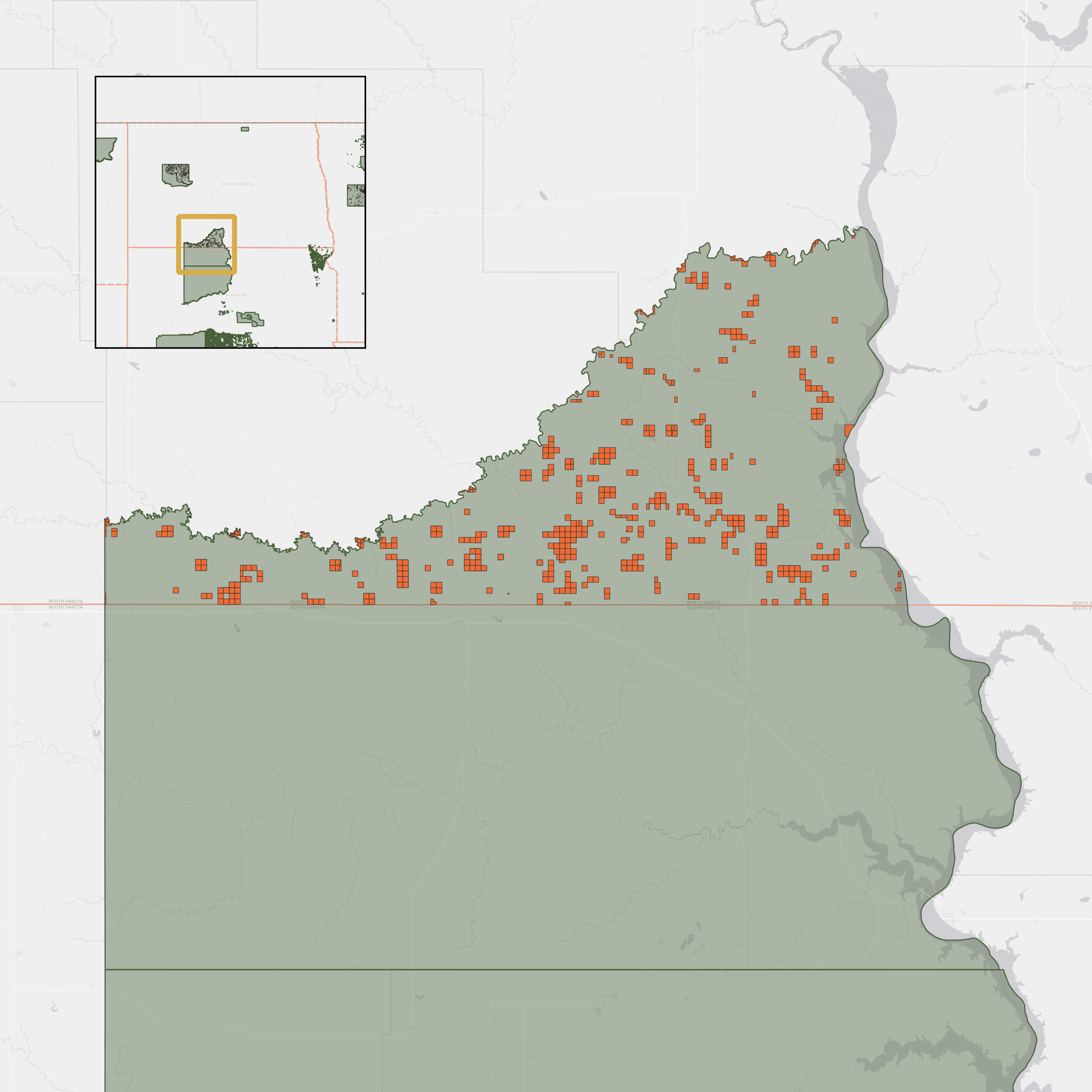

Before Jon Eagle Sr. began working for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, he was an equine therapist for over 36 years, linking horses with and providing support to children, families, and communities both on his ranch and on the road. The work reinforced his familiarity with the land, and allowed him to explore the rolling hills, plains, and buttes of the sixth-largest reservation in the United States. But when he became Standing Rock’s tribal historic preservation officer, he learned that the land still held surprises, the biggest one being that much of that land didn’t belong to the tribe. Standing Rock straddles North and South Dakota, and both states own thousands of acres within the tribe’s reservation boundaries.

“They don’t talk to us at all about it,” Eagle said. “I wasn’t even aware that there were lands like that here.”

On the North Dakota side, nearly 23,500 acres of Standing Rock are managed by the state, along with another 70,000 of subsurface acres, a land classification that refers to underground resources, including oil and gas. The combined 93,500 acres, known as trust lands, are held and managed by the state and produce revenue for its public schools and the Bank of North Dakota. The amount of reservation land South Dakota controls is unknown; the state does not make public its trust land data and did not supply it after a public records request.

And Standing Rock isn’t alone.

Data analyzed by Grist and High Country News reveals that a combined 1.6 million surface and subsurface acres of state trust lands lie within the borders of 83 federal Indian reservations in 10 states.

State trust lands, which are managed by state agencies, generate millions of dollars for public schools, universities, penitentiaries, hospitals, and other state institutions, typically through grazing, logging, mining, and oil and gas production. Although federal Indian reservations were established for the use and governance of Indigenous nations and their citizens, the existence of state trust lands reveals a truth: States rely on Indigenous land and resources to support non-Indigenous institutions and offset state taxpayer dollars for non-Indigenous people. Tribal nations have no control over this land, and many states do not consult with tribes about how it’s used.

Even in the obscure world of trust lands, states’ holdings within reservations have been almost completely unknown until now. Many of the experts Grist and High Country News reached out to, including longtime policymakers and leaders on Indigenous issues, were unfamiliar with state trust lands’ history and acreage. However, what sources did make clear is that the presence of state lands on reservations complicates issues of tribal jurisdiction in regards to land use and management and undercuts tribal sovereignty. According to Rob Williams, University of Arizona law professor and citizen of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, this has broad implications for everything from the handling of missing and murdered Indigenous people to tribal nations’ ability to confront climate change.

“When there’s clarity about jurisdiction over Indian lands, it is easier for tribes to work with others to protect public safety, public health, and the natural environment,” said Bryan Newland, assistant secretary for Indian Affairs at the Department of Interior and citizen of the Bay Mills Indian Community. “It’s been the longstanding policy of the department to reduce ‘checkerboard’ jurisdiction within reservations by consolidating tribal lands and strengthening the ability of tribes to exercise their sovereign authorities over their own lands.”

The creation of Indian reservations was followed closely by states entering the union, as were successful attempts by state governments to carve up and dissolve those tribal lands.

Once states became part of the U.S., they received millions of acres of recently ceded tribal lands, many of which became trust lands. But as more settlers moved west, states pushed for more land. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the U.S. government responded by carving up Indian reservations, parceling out small amounts of land to individual tribal members, then handing over “surplus” lands for states, settlers, and federal projects. Known as the Allotment Era, the federal policy moved approximately 90 million acres of reservation lands nationwide from tribal hands to non-Native ownership.

According to Monte Mills, professor of law at the University of Washington and director of the Native American Law Center, allotment served a dual purpose: It broke up tribal power and gave non-Native citizens access to tribal lands and natural resources.

The allotment system, Mills explained, provided “a whole other set of opportunities for non-Indian settlers to get access to surplus lands and for the states to come in and get more state trust lands on lands that had been expressly off-limits.”

As Rob Williams put it, “The conquest was by law.”

“The implications of that policy are just devastating,” Williams said. “It’s hard to think of a single problem in Indian law that you can’t blame it in part on.”