Water usage and what we get in return is a challenging issue to track when…

The post We Earthlings: Apples vs. Almonds — Water Use & Fiber Content appeared first on Earth911.

Water usage and what we get in return is a challenging issue to track when…

The post We Earthlings: Apples vs. Almonds — Water Use & Fiber Content appeared first on Earth911.

Every year on April 22, earth-conscious people around the world celebrate the planet we live…

The post 5 Simple Earth Day Crafts Your Kids Will Love appeared first on Earth911.

Levels of the three “most important” greenhouse gases — methane, carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide — in the atmosphere reached record highs again in 2023, according to research conducted by scientists with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)’s Global Monitoring Laboratory (GML).

Air samples taken by GML indicated that levels of the heat-trapping gases did not rise as fast as the record leaps of recent years, but were still in accordance with sharp increases recorded in the past decade, a press release from NOAA said.

“NOAA’s long-term air sampling program is essential for tracking causes of climate change and for supporting the U.S. efforts to establish an integrated national greenhouse gas measuring, monitoring and information system,” said Vanda Grubišić, GML’s director, in the press release. “As these numbers show, we still have a lot of work to do to make meaningful progress in reducing the amount of greenhouse gases accumulating in the atmosphere.”

Earth’s average surface carbon dioxide concentration for all of 2023 was 419.3 parts per million (ppm) — up 2.8 ppm over the course of the year. It was the 12th year in a row that carbon dioxide jumped more than two ppm — continuing the most sustained carbon increase rate in NOAA’s 65-year monitoring record.

Even three years in a row of carbon increases of two ppm or higher had not been recorded before 2014. Carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere have risen to 50 percent higher than in pre-industrial times.

“The 2023 increase is the third-largest in the past decade, likely a result of an ongoing increase of fossil fuel CO2 emissions, coupled with increased fire emissions possibly as a result of the transition from La Niña to El Niño,” said Xin Lan, a scientist with the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences and head of the effort by GML to integrate data from NOAA’s Global Greenhouse Gas Reference Network, which keeps track of greenhouse gas trends worldwide, in the press release.

Levels of methane in the atmosphere increased to a 1,922.6 parts per billion (ppb) average. Methane, while less abundant than carbon, traps more heat. The increase in atmospheric methane last year over 2022 levels was 10.9 ppb, which was lower than previous record rates in 2021 and 2022. However, it was the fifth highest since methane began to increase again in 2007. Current levels of atmospheric methane are more than 160 percent above those of pre-industrial levels.

Last year’s nitrous oxide levels rose to 336.7 ppb — a jump of one ppb. Nitrous oxide is the third most important greenhouse gas produced by humans.

“Increases in atmospheric nitrous oxide during recent decades are mainly from use of nitrogen fertilizer and manure from the expansion and intensification of agriculture. Nitrous oxide concentrations are 25% higher than the pre-industrial level of 270 ppb,” NOAA said.

More than 15,000 samples were collected by GML by global monitoring stations last year. They were then analyzed in a Boulder, Colorado, laboratory. The NOAA-run Global Greenhouse Gas Reference Network (GGGRN) includes roughly 53 sampling sites worldwide and 20 tall tower sites, as well as North American aircraft operation sites.

NOAA said carbon dioxide is the most important greenhouse gas contributing to climate change. Carbon produced by humans has gone up from 10.9 billion tons annually in the 1960s to roughly 36.6 billion tons in 2023. The Global Carbon Project uses GGGRN measurements to calculate net impacts of global carbon sinks and emissions and said last year’s carbon emissions set a new record.

“The amount of CO2 in the atmosphere today is comparable to where it was around 4.3 million years ago during the mid-Pliocene epoch, when sea level was about 75 feet higher than today, the average temperature was 7 degrees Fahrenheit higher than in pre-industrial times, and large forests occupied areas of the Arctic that are now tundra,” the press release said.

Approximately half of fossil fuel emissions have been absorbed into the surface of the planet by land and ocean ecosystems like grasslands and forests. Ocean carbon contributes to acidification, which impacts marine life as well as humans. The world’s oceans have absorbed roughly 90 percent of excess atmospheric heat trapped by greenhouse gases.

A study by NASA and NOAA scientists in 2022 — coupled with further research by NOAA in 2023 — suggests that upwards of 85 percent of the methane emissions increase between 2006 and 2021 came from higher microbial emissions from agriculture, livestock, waste generated by humans, including agriculture, wetlands and other water-based sources. The balance was found to be caused by increased fossil fuel emissions.

Scientists with NOAA are looking into the likelihood that climate change is leading to wetlands producing increasing methane emissions, which in turn influence the climate in a feedback loop. However, the precise reasons for the recent rise in methane are not completely understood.

“In addition to the record high methane growth in 2020-2022, we also observed sharp changes in the isotope composition of the methane that indicates an even more dominant role of microbial emission increase,” Lan said in the press release.

The post 3 ‘Most Important’ Greenhouse Gases Reached Record Highs Again Last Year: NOAA Scientists appeared first on EcoWatch.

This week, the European Court of Human Rights could make a landmark ruling that governments have an obligation to protect people from the adverse impacts of climate change.

Judges will rule on three distinct cases concerning whether people’s human rights were breached when governments failed to protect them from the ravages of a warming planet.

“We all are trying to achieve the same goal,” said Catarina Mota, a 23-year-old plaintiff in one of the cases, as Reuters reported. “A win in any one of the three cases will be a win for everyone.”

One of the cases — Verein KlimaSeniorinnen Schweiz and Others v. Switzerland — concerns a complaint brought by members of a Swiss association of older women who are concerned about the impacts of global heating on their health and living conditions, the European Court of Human Rights said in a press release.

The group of women claim that Bern’s failure to reduce emissions that aligns with a pathway to limit global heating to 1.5 degrees Celsius was in breach of their right to life, reported Reuters.

They cited a report by the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change that found older adults and women were some of those most at risk of death from extreme temperatures during heat waves.

Attorneys for the women are looking for a decision that could compel Switzerland to pick up the pace of its carbon emissions reductions.

Another of the cases — Carême v. France — involves a former mayor of the city of Grande-Synthe who says France has not taken enough action to prevent global heating, which equates to a violation of “the right to respect for private and family life” and “the right to life,” the press release said.

In a third case — Duarte Agostinho and Others v. Portugal and 32 Others — plaintiffs say current and future climate change impacts are the responsibility of states and affect their well-being, mental health and “the peaceful enjoyment of their homes.”

“The three cases are quite distinct in terms of who’s bringing the case, which government or governments is being sued, and what the ask is in the case,” said Lucy Maxwell, Climate Litigation Network’s co-director, as Reuters reported.

The rulings of the panel of 17 judges will not be able to be appealed.

Maxwell added that the court could deem a case too complex for its framework and decide it must be sent to a national forum.

Meanwhile, some governments involved have said the lawsuits are inadmissible. Switzerland claimed the court of human rights is not the “supreme court” regarding environmental cases.

Whatever the outcome, the rulings will provide precedent for future cases on how climate change impacts the right of humans to a habitable planet.

Maxwell said a decision against the governments of Portugal or Switzerland would “send a clear message that governments have legal duties to significantly increase their efforts to combat climate change in order to protect human rights,” reported Reuters.

If countries did not amend their emissions reduction goals for 2030 in response to the rulings, additional litigation could be brought in national courts.

“If successful… it would be the most important thing to happen for the climate in Europe since the Paris Agreement because it kind of has the effect of a regional European treaty,” said Ruth Delbaere, a civic movement senior legal campaigner for Avaaz, which assisted with fundraising for legal fees for the Portuguese youths, as Reuters reported.

The rulings will be the first by the European Court of Human Rights on whether policies related to climate change violate people’s human rights as set forth in the European Convention.

Maxwell said the rulings could also influence decisions in other countries. Climate cases concerning violations of human rights are currently being considered in Brazil, Peru, South Korea and Australia.

“They will be looking at what happens in Europe and there will be ripple effects well outside,” Maxwell said.

The rulings by the European Court of Human Rights will be delivered at a public hearing on Tuesday in Strasbourg, France.

The post European Court of Human Rights to Rule on Whether Governments Must Protect People From Climate Change appeared first on EcoWatch.

Without curtains, blinds, or other window covers, rooms can heat up quickly when the afternoon sun streams through a window. Close the curtain or pull down the blind, and the room may cool down, but you lose views of the garden or backyard. Even window film can still offer some transparency, but it often includes tinting that can disrupt the view. Scientists have been working to solve this dilemma, and they may have just made it happen with a newly developed clear window coating.

A team of researchers from University of Notre Dame and Kyung Hee University in Seoul, South Korea have developed a window coating that fully blocks heat, even from the afternoon sun.

“The angle between the sunshine and your window is always changing,” Tengfei Luo, lead author of the study and the Dorini Family Professor for Energy Studies at the University of Notre Dame, said in a statement. “Our coating maintains functionality and efficiency whatever the sun’s position in the sky.”

The researchers explained that while heat-blocking window coatings and coverings are not a new concept, coatings tested in recent studies tend to let ultraviolet and infrared light through when the sun is positioned at certain angles.

Two team members, Luo and Seongmin Kim, postdoctoral associate at the University of Notre Dame, previously developed a window coating made from silica, alumina and titanium oxide with an additional micrometer-thick silicon polymer to better reflect thermal radiation and block heat from coming through the windows.

The team then needed to optimize the order of the layers of the coating to block heat from all angles throughout the day. They used quantum computing to make this happen, finally settling on an optimized window coating that stayed transparent but reduced the temperature in a room by 5.4 to 7.2 degrees Celsius. The researchers published these findings in the journal Cell Reports Physical Science.

“Like polarized sunglasses, our coating lessens the intensity of incoming light, but, unlike sunglasses, our coating remains clear and effective even when you tilt it at different angles,” Luo explained.

The resulting window coating could be used not just for homes and residential buildings but also on vehicles to reduce heat gain and reliance on air conditioning. According to the study, cities throughout the U.S. could reduce energy use for cooling by up to 97.5 megaJoules (MJ) per square meter, and the coating could help cities reach up to 50.5% of cooling energy savings when applied to conventional windows.

This could be particularly important in reducing emissions, as the International Energy Agency reported that air conditioning usage currently accounts for about 10% of total global electricity consumption, and the agency estimated that global energy demand from air conditioning could triple by 2050.

The post Scientists Develop Window Coating That Blocks Heat While Letting in Light appeared first on EcoWatch.

Earth Day, celebrated annually on April 22, is a reminder of our responsibility as part…

The post Get Ready To Celebrate Earth Day 2024! appeared first on Earth911.

Youth face the greatest impact of climate change, and will certainly have to live with…

The post Earth911 Podcast: Ecoteens Founder Pragna Nidumolu On Activating Youth Environmental Networks appeared first on Earth911.

Few issues are as divisive among American environmentalists as nuclear energy. Concerns about nuclear waste storage and safety, particularly in the wake of the 1979 Three Mile Island reactor meltdown in Pennsylvania, helped spur the retirement of nuclear power plants across the country. Nuclear energy’s proponents, however, counter that nuclear power has historically been among the safest forms of power generation, and that the consistent carbon-free energy it generates makes it an essential tool in the fight against global warming.

But this well-worn debate may not actually be the one that determines the future of nuclear energy in the United States. More decisive is the unresolved question of whether the U.S. actually has the practical ability to build new nuclear plants at all.

The answer to this question may hinge on what happens in the wake of a construction project that’s reaching completion near Waynesboro, Georgia, where the second in a pair of new nuclear reactors is scheduled to enter commercial service at some point over the next three months. Each reactor has the capacity to power half a million homes and businesses annually without emitting greenhouse gases. Despite this, they are hardly viewed as an unambiguous success.

The construction of those reactors — Units 3 and 4 of Plant Vogtle, the first U.S. nuclear reactors built from scratch in decades — was a yearslong saga whose delays and budget overruns drove the giant nuclear company Westinghouse into bankruptcy. The reactors, first approved by Georgia regulators in 2009, are reckoned to be the most expensive infrastructure project of any kind in American history, at a total cost of $35 billion. That’s nearly double the original budget of the project, which is set to cross the finish line seven years behind schedule. Much of the cost was ultimately borne by Georgia residents, whose energy bills have ballooned to pay off a portion of the overruns.

“It’s a simple fact that Vogtle had disastrous cost overruns and delays, and you have to stare that fact in the face,” said John Parsons, a researcher at MIT’s Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research. “It’s also possible that nuclear, if we can do it, is a valuable contribution to the system, but we need to learn how to do it cheaper than we’ve done so far. I would hate to throw away all the gains that we’ve learned from doing it.”

What kind of learning experience Vogtle ends up being may well come down to how it’s interpreted by the state and regional utility officials who approve new sources of power. Many are likely looking at the monumental expense and difficulty of building Vogtle and thinking they’d be foolish to try their hand at new nuclear power. Other energy officials, however, say those delays and overruns are the reason they’d be foolish not to.

The case for building more nuclear plants in the wake of Vogtle rests on a simple argument: Because the new reactors were the first newly built American nuclear plant to come online since 1993 — and the first to begin construction since the 1970s — many of their challenges were either unique to a first-of-a-kind reactor design or a result of the loss of industrial knowledge since the decline of the nuclear industry. Therefore, they might not necessarily recur in a future project, which could take advantage of the finalized reactor design and the know-how that had to be generated from scratch during Vogtle.

The Biden administration, which sees nuclear energy as an important component of its plan to get the U.S. to net-zero emissions by 2050, is betting that Vogtle can pave the way for a rebirth of the nuclear industry.

The generational gap between Vogtle and previous nuclear projects meant that the workforce and supply chain needed to build a nuclear plant had to be rebuilt for the new units. Their construction involved training some 13,000 technicians, according to Julie Kozeracki, a senior advisor at the Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office, a once-obscure agency that has become one of the federal government’s main conduits for climate investments under the Biden administration.

When Vogtle’s Units 3 and 4 were approved by Georgia regulators in 2009, the reactor model, known as an AP1000, had never before been built. (It was Westinghouse’s flagship model, combining massive generation capacity with new “passive safety” features, which allow reactors to remain cooled and safe without human intervention, external power, or emergency generators in the case of an accident.) It later emerged that the reactor’s developer, Westinghouse, had not even fully completed the design before starting construction, causing a significant share of the project’s costly setbacks. While that was bad news for Georgians, it could mean a smoother path ahead for future reactors.

“In the course of building Vogtle,” Kozeracki told Grist, “we have now addressed three of the biggest challenges: the incomplete design, the immature supply chain, and the untrained workforce.”

These factors helped bring down the cost of Unit 4 by 30 percent compared to Unit 3, Kozeracki said, adding that a hypothetical Unit 5 would be even cheaper. Furthermore, as a result of the Inflation Reduction Act, the climate-focused law that Congress passed in 2022, any new nuclear reactor would receive somewhere between 30 and 50 percent of its costs back in tax credits.

“We should be capitalizing on those hard-won lessons and building 10 or 20 more [AP1000s],” Kozeracki said.

Despite this optimism, however, no U.S. utility is currently building a new nuclear reactor. Part of the reason may be that it’s already too late to capitalize on the advantages of the Vogtle experience. For one thing, the 13,000 workers who assembled Vogtle may not all be available for a new gig.

“The trained workforce is a rapidly depreciating asset for the nuclear industry,” said John Quiggin, an economist at the University of Queensland, in an email. “Once the job is finished, workers move on or retire, subcontractors go out of business, the engineering and design groups are broken up and their tacit knowledge is lost. If a new project is started in, say, five years, it will have to do most of its recruiting from scratch.”

In Quiggin’s view, the opportunity has already passed, as much of the physical construction at Plant Vogtle happened years ago. “You can’t go back and say, ‘Look, we’ve got the team, we know what we did wrong last time, we’re going to do it better this time.’ It’ll be a totally new group of people doing it,” he said in an interview.

“It would have been better to start five years ago,” Kozeracki acknowledged. “But the second best time is right now.”

The federal government has put money on the table, but whether a new nuclear plant will actually get built is ultimately in the hands of a constellation of players including the nuclear industry, utility companies, and utility commissions, who would have to work together and overcome their current stalemate. None of them are clamoring to shoulder the risk of taking the first step.

“Everybody’s hoping that someone else would solve the cost problem,” Parsons said.

Utility commissioners — the state-level officials, often in elected positions, whose approval would be needed to site a future reactor — are wary of being blamed for passing on potential cost overruns to ratepayers.

“It would just be surprising for me if a Public Service Commission signed off on another AP1000 given how badly the last ones went,” said Matt Bowen, a researcher at Columbia’s Center on Global Energy Policy.

If more nuclear energy is built soon, it will most likely be in the Southeast, where power companies operate under what’s called a “vertically integrated monopoly” profit model, meaning they do not participate in wholesale energy markets but rather generate energy themselves and then sell it directly to customers.

Under this model, utilities are guaranteed a return on any investment their shareholders make, which is paid for by their customers at rates set by the state-level utility commissions. Many ratepayer advocates accuse these commissions of effectively rubber-stamping utility demands as a result of regulatory capture — at the expense of customers who are unable to choose a different power company. But this same dynamic means that vertically integrated utilities are in the best position to build something as expensive as a nuclear plant.

“Their primary business model is capital expenditure,” explained Tyler Norris, a Duke University doctoral fellow and former special advisor at the Department of Energy. “The way they make money is by investing capital, primarily in generation capacity or transmission upgrades. They have an inherent incentive to spend money; they make more money the more they spend.”

Under the regulatory compact between states and utilities, it is utility commissioners’ job to make sure those expenditures (which ultimately, after all, come from ratepayer money) are “just and reasonable.”

Tim Echols, a member of Georgia’s Public Service Commission, said in an email that he would not approve another nuclear reactor in Georgia in the absence of “some sort of federal financial backstop” to protect against the risk of a repeat of the Vogtle experience.

“I haven’t seen any other [utility commission] raise their hand to build a nuclear reactor,” added Echols, who is also the chair of a committee on nuclear issues at the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners.

Kozeracki, of the Department of Energy, said that private-sector nuclear industry players have also asked for such a backstop in the form of a federal cost overrun insurance program, which would require Congressional legislation. However, she added that it might be incumbent upon industry figures to explain just how much more capacity to build such a backstop would give them.

“The real piece that’s missing there is a compelling plan from the nuclear industry for what they would deliver with something like a cost overrun insurance program,” Kozeracki said.

There is an ongoing debate among nuclear advocates about whether a different type of reactor, such as the so-called small modular reactors currently in development, is a more viable solution than the AP1000. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission has issued a permit for the Tennessee Valley Authority to build one such reactor. But the excitement around SMRs has somewhat waned since the cancellation of a much-anticipated project in November. Experts told Grist that some, but not all, of the knowledge and lessons gained through the Vogtle experience would carry over to a new project that was not an AP1000.

The search for new nuclear solutions is coinciding with what could be a dramatic juncture in the history of American energy planning. In recent months, utilities across the country have reported anticipating massive increases in demand for electricity, which had remained relatively flat for two decades. A December report from the consulting firm Grid Strategies found that grid planners’ five-year forecasts for the growth of their power loads had nearly doubled over the last year.

The growth in demand is largely attributed to a mix of new data centers, many of which will power artificial intelligence, as well as new industrial sites.

For James Krellenstein, co-founder of the nuclear energy consultancy Alva Energy, this new load growth “dramatically changes the calculus in favor of nuclear.”

“Facing both the need to decrease carbon emissions while having to increase the amount of power that we need, nuclear is a natural technology for that challenge,” Krellenstein added.

So far, however, utilities have responded instead by seeking to rapidly expand fossil fuel generation — in particular, by building new natural gas plants.

“We’re seeing utilities put forward very large gas expansion plans, and this is eating nuclear’s lunch,” said Duke University’s Norris.

Kozeracki characterized the utilities’ plans as shortsighted. “I recognize that natural gas may feel like the easy button, but I should hope that folks are able to account for the cost and benefits of decarbonizing resiliently and make choices their children will be proud of, which I think would be starting new nuclear units now,” she said.

Norris urged caution in accepting the largest estimates of forecasted electricity demand. “Utilities have every incentive to characterize a worst case scenario here for extreme load growth, and not seriously consider demand response solutions, so that they can justify very large capital expenditures for capacity,” Norris said. “That’s why it’s so important that the clean energy and climate community be very engaged in these state level resource planning processes.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Georgia’s Vogtle plant could herald the beginning — or end — of a new nuclear era on Apr 8, 2024.

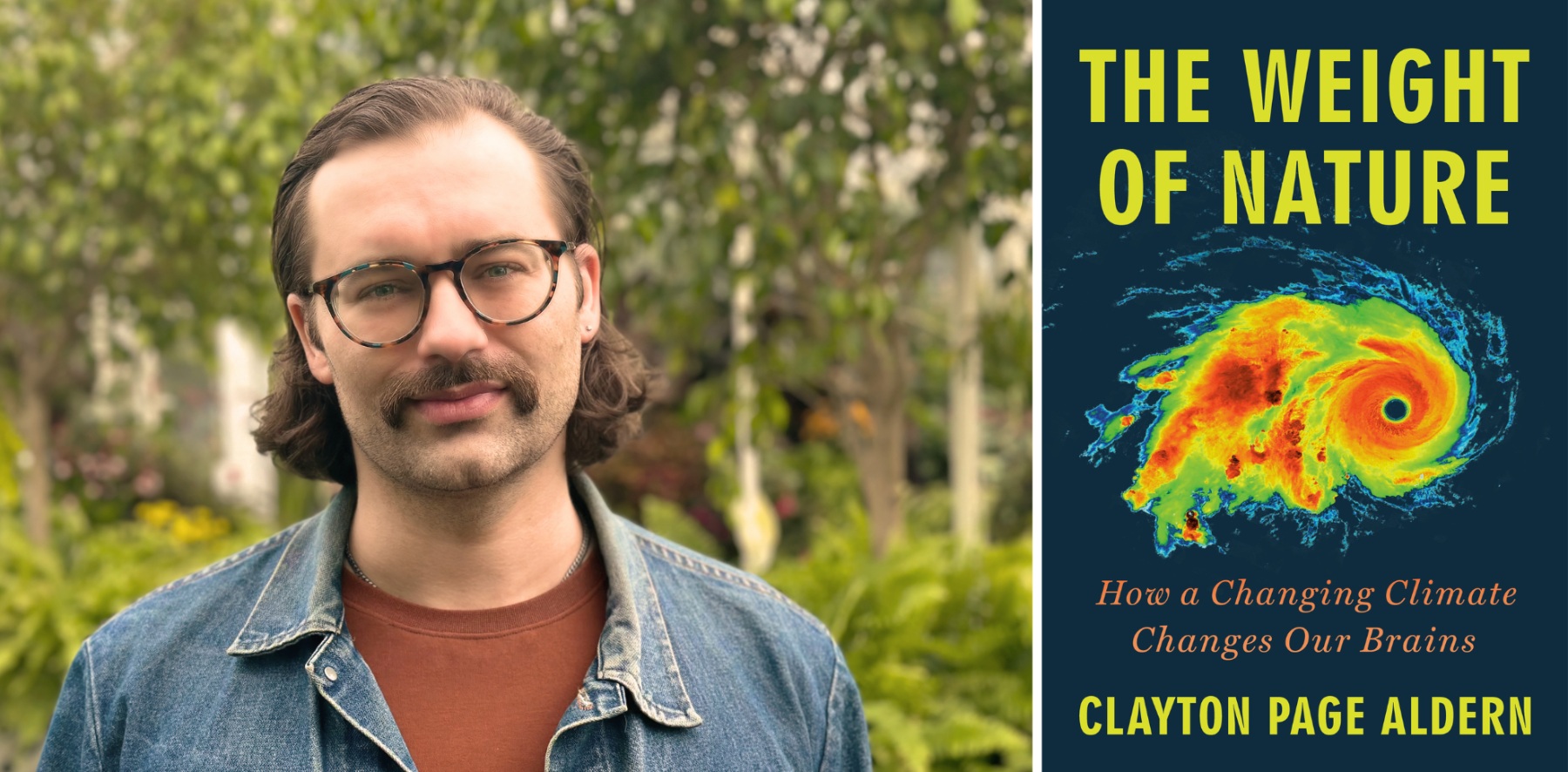

This story is excerpted from THE WEIGHT OF NATURE: How a Changing Climate Changes Our Brains, available April 9, 2024, from Dutton, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group.

Imagine you are a clown fish. A juvenile clown fish, specifically, in the year 2100. You live near a coral reef. You are orange and white, which doesn’t really matter. What matters is that you have these little ear stones called otoliths in your inner ear, and when sound waves pass through the water and then through your body, these otoliths move and displace tiny hair cells, which trigger electrochemical signals in your auditory nerve. Nemo, you are hearing.

But you are not hearing well. In this version of century’s end, humankind has managed to pump the climate brakes a smidge, but it has not reversed the trends that were apparent a hundred years earlier. In this 2100, atmospheric carbon dioxide levels have risen from 400 parts per million at the turn of the millennium to 600 parts per million — a middle‑of‑the-road forecast. For you and your otoliths, this increase in carbon dioxide is significant, because your ear stones are made of calcium carbonate, a carbon-based salt, and ocean acidification makes them grow larger. Your ear stones are big and clunky, and the clicks and chirps of resident crustaceans and all the larger reef fish have gone all screwy. Normally, you would avoid these noises, because they suggest predatory danger. Instead, you swim toward them, as a person wearing headphones might walk into an intersection, oblivious to the honking truck with the faulty brakes. Nobody will make a movie about your life, Nemo, because nobody will find you.

It’s not a toy example. In 2011, an international team of researchers led by Hong Young Yan at the Academia Sinica, in Taiwan, simulated these kinds of future acidic conditions in seawater tanks. A previous study had found that ocean acidification could compromise young fishes’ abilities to distinguish between odors of friends and foes, leaving them attracted to smells they’d usually avoid. At the highest levels of acidification, the fish failed to respond to olfactory signals at all. Hong and his colleagues suspected the same phenomenon might apply to fish ears. Rearing dozens of clown fish in tanks of varying carbon dioxide concentrations, the researchers tested their hypothesis by placing waterproof speakers in the water, playing recordings from predator-rich reefs, and assessing whether the fish avoided the source of the sounds. In all but the present-day control conditions, the fish failed to swim away. It was like they couldn’t hear the danger.

In Hong’s study, though, it’s not exactly clear if the whole story is a story of otolith inflation. Other experiments had indeed found that high ocean acidity could spur growth in fish ear stones, but Hong and his colleagues hadn’t actually noticed any in theirs. Besides, marine biologists who later mathematically modeled the effects of oversize otoliths concluded that bigger stones would likely increase the sensitivity of fish ears — which, who knows, “could prove to be beneficial or detrimental, depending on how a fish perceives this increased sensitivity.” The ability to attune to distant sounds could be useful for navigation. On the other hand, maybe ear stones would just pick up more background noise from the sea, and the din of this marine cocktail party would drown out useful vibrations. The researchers didn’t know.

The uncertainty with the otoliths led Hong and his colleagues to conclude that perhaps the carbon dioxide was doing something else — something more sinister in its subtlety. Perhaps, instead, the gas was directly interfering with the fishes’ nervous systems: Perhaps the trouble with their hearing wasn’t exclusively a problem of sensory organs, but rather a manifestation of something more fundamental. Perhaps the fish brains couldn’t process the auditory signals they were receiving from their inner ears.

The following year, a colleague of Hong’s, one Philip Munday at James Cook University in Queensland, Australia, appeared to confirm this suspicion. His theory had the look of a hijacking.

A neuron is like a house: insulated, occasionally permeable, maybe a little leaky. Just as one might open a window during a stuffy party to let in a bit of cool air, brain cells take advantage of physical differences across their walls in order to keep the neural conversation flowing. In the case of nervous systems, the differentials don’t come with respect to temperature, though; they’re electrical. Within living bodies float various ions — potassium, sodium, chloride, and the like — and because they’ve gained or lost an electron here or there, they’re all electrically charged. The relative balance of these atoms inside and outside a given neuron induces a voltage difference across the cell’s membrane: Compared to the outside, the inside of most neurons is more negatively charged. But a brain cell’s walls have windows too, and when you open them, ions can flow through, spurring electrical changes.

In practice, a neuron’s windows are proteins spanning their membranes. Like a house’s, they come in a cornucopia of shapes and sizes, and while you can’t fit a couch through a porthole, a window is still a window when it comes to those physical differentials. If it’s hot inside and cold outside, opening one will always cool you down.

Until it doesn’t.

Here is the clown fish neural hijacking proposed by Philip Munday. What he and his colleagues hypothesized was that excess carbon dioxide in seawater leads to an irregular accumulation of bicarbonate molecules inside fish neurons. The problem for neuronal signaling is that this bicarbonate also carries an electrical charge, and too much of it inside the cells ultimately causes a reversal of the normal electrical conditions. At the neural house party, now it’s colder inside than out. When you open the windows — the ion channels — atoms flow in the opposite direction.

Munday’s theory applied to a particular type of ion channel: one responsible for inhibiting neural activity. One of the things all nervous systems do is balance excitation and inhibition. Too much of the former and you get something like a seizure; too much of the latter and you get something like a coma — it’s in the balance we find the richness of experience. But with a reversal of electrical conditions, Munday’s inhibitory channels become excitatory. And then? All bets are off. For a brain, it would be like pressing a bunch of random buttons in a cockpit and hoping the plane stays in the air. In clown fish, if Munday is right, the acidic seawater appears to short-circuit the fishes’ sense of smell and hearing, and they swim toward peril. It is difficult to ignore the question of what the rest of us might be swimming toward.

From THE WEIGHT OF NATURE: How a Changing Climate Changes Our Brains by Clayton Page Aldern, to be published on April 9, 2024, by Dutton, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2024 by Clayton Page Aldern.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Climate change is rewiring fish brains — and probably ours, too on Apr 8, 2024.

I scream, you scream, we all scream when it comes to recycling ice cream cartons….

The post Recycling Mystery: Ice Cream Cartons appeared first on Earth911.