Homemade is more sustainable than a commercial product from a huge corporation. At least, it…

The post Homebrewing More Sustainably appeared first on Earth911.

Homemade is more sustainable than a commercial product from a huge corporation. At least, it…

The post Homebrewing More Sustainably appeared first on Earth911.

Our world was radically changed about three years ago at the start of the 2020…

The post Designing Sustainable Outdoor Living Spaces appeared first on Earth911.

This story was co-published with Rappler, a Philippines-based online news publication.

Tina Batalla had owned a bicycle for many years. But it wasn’t until the pandemic that the then-21-year-old university student really started using it to get around Metro Manila after a friend invited her out on a rainy day ride in June 2020.

“There were no cars, and it felt safe,” she said. Riding on streets free of the car traffic that has earned Metro Manila a reputation as one of the most congested urban areas in the world built Batalla’s confidence that she could get around by bike despite not being a “hard-core cyclist.”

“Re-experiencing the city I grew up in clicked a switch in me, and I felt like this is something I want to continue doing,” she said.

Batalla is one of many Filipinos — and people around the world — who embraced biking in a new way during the pandemic. But now, the country’s climate-friendliest mode of transportation besides walking is at risk, as national lawmakers slash the budget for bike lanes — and Filipino cyclists are organizing to ensure that the silver lining of the pandemic leads to lasting improvements in bicycle infrastructure.

COVID-19 pushed Metro Manila’s already-struggling public transit system into crisis: The government shut down mass transportation in the city for two and half months in an effort to contain the virus, and after the shutdown lifted, capacity limits forced commuters to wait for up to three hours just to board the Metro Rail Transit, or MRT. Similar wait times plagued buses and jeepneys, iconically Filipino public transit vehicles.

Bike owners outnumber car owners 5 to 1 in Metro Manila, a metropolitan area made up of 16 interconnected cities. The long lines at transit stations left cycling as the most viable alternative for many. Hospitals began setting up bike parking to accommodate the droves of doctors and nurses cycling to work. Local city governments used traffic cones or simple stripes of paint to outline pop-up bike lanes, and the national government’s Department of Transportation, or DOTr, created a new office to focus explicitly on active transport (which includes biking, walking, scooters, and the like). By June 2021, 313 kilometers (194 miles) of new bike lanes had been added to streets within Metro Manila through the combined efforts of local and national governments.

“The pandemic was a huge factor in pushing the Philippine government to prioritize and promote active mobility,” said Eldon Joshua Dionisio, the program manager of DOTr’s active transport office, which has grown to include 14 employees.

Metro Manila’s pandemic cycling boom mirrors a phenomenon experienced in cities all over the world. In the U.S., people began cycling at “unprecedented levels” and bike sales surged. In Europe, more than $1.1 billion dollars worth of biking infrastructure was built between March and October 2020, with cities like Paris and Brussels leading the way. And in South America, cities like Lima and Bogotá began building out bike lanes along routes that had been identified years beforehand but never installed until the pandemic drove more cyclists onto the streets.

All that pedal-pushing has come with a host of benefits. Elijah Go Tian, a lead on the Low Carbon Transport Project at the United Nations Development Programme in the Philippines, noted that switching from cars to bikes drastically lowers climate change-causing emissions. The daily travel emissions of people who cycle are 84 percent lower than those of non-cyclists, according to one Oxford study. More bike trips and fewer car trips also makes for less air pollution, which costs the Philippines approximately $87 billion annually in healthcare costs and productivity loss, according to a 2021 study. Bikes can also reduce car traffic and noise pollution, help riders stay healthier and more active, and provide greater agency over one’s own mobility.

Despite this multitude of benefits, the gains of the last three years are not guaranteed to persist in the Philippines. Though the national government earmarked 4 billion pesos (around $71 million) for active transport from 2020 to 2023, the budget has been cut each year, down to 500 million pesos for 2024 from a high of 2 billion pesos in 2022.

“We have decision-makers who are still car-centric,” Dionisio said.

That drop in funding for the office that oversees safe biking infrastructure could slow progress considerably: A recent survey found that 4 out of 5 household heads in the Philippines agree that more people would use bikes as transportation if the roads were safer.

“The momentum has been slowing down a bit,” said Tian.

Decision-makers in business and politics come primarily from the car-owning class, which can exacerbate inequality, said Earl Decena, a sustainable transportation officer at the business association Makati Business Club. Though only 6 percent of Filipinos own cars, biking has been associated with poverty in the past, and sometimes discriminated against in both the public and private sector.

“The norm, especially pre-pandemic, has been that if you’re on a bicycle, you’re not treated the same way you would be treated if you came in a vehicle,” he said. “There’s an undertone of, ‘If you’re in a car, you can probably pay more.’”

When that attitude gets scaled up to the level of policy, it can enshrine preferential treatment for car owners — rather than the 94 percent of Filipinos who don’t own cars — into law.

Fractured and uneven oversight of biking infrastructure also causes problems for bikers, explained Ramir Angeles. Angeles is a transportation engineer for the government of Quezon City, one of the cities that makes up Metro Manila. Since local government units oversee local roads, while the national government oversees national roads, maintenance of bike lanes can be uneven.

“Bike lanes have now become a much more hostile environment than they were” during the height of the pandemic, said Angeles, adding that the return to pre-pandemic levels of car traffic has escalated the sense of danger for many bikers. And in some parts of Metro Manila, bike infrastructure is actively “being removed or downgraded,” he added.

Batalla has experienced the latter firsthand. When she learned in February that the bike lanes along Ayala Avenue, a major thoroughfare in one of Metro Manila’s busiest business districts, were going to be converted into dreaded “sharrows,” which would force bikers to share a lane with public transit vehicles like buses and jeepneys while leaving private vehicle lanes untouched, she was outraged.

“These bike lanes were so important for the safety of our essential workers … What happens if we have cities that keep on making them work but don’t actually care about their safety?” she asked. “It really hit me that if we did not get on the streets, speak up and organize, those lanes would basically be lost forever.”

Batalla’s response to that frustration was to organize. What started as a one-off group ride in protest of the Ayala Avenue plan eventually grew into the #MakeItSafer campaign, part of a larger transportation advocacy group called the Move As One Coalition. The campaign convinced Ayala Land, the decision-making entity behind the bike lane conversion, to enter into a dialogue with advocates to work towards a different solution. And when Ayala Land “rejected the community’s proposed safety interventions,” Move As One staged another protest ride in July, this time to pressure the decision-makers to fix bike lanes and strengthen enforcement to keep motorcycles out of bike lanes.

Batalla’s experience points to a factor that could help maintain Metro Manila’s momentum: the vibrant community of bikers that has been expanding rapidly since 2020. Cycling clubs started by those riders have been popping up all over the metro area, facilitating group rides, pop-up events, and protests. The result is a network of people across the city who are primed to mobilize to protect bikers’ interests.

And even if cycling isn’t accelerating as quickly as it did in 2020, the numbers of bikers on the roads remain high. A bike count in June 2022 found about 54,000 cyclists on main roads over four hours. Even that number, which Angeles said is an undercount and which was only conducted in four of the 16 cities that make up Metro Manila, makes clear that cyclists remain a sizable demographic.

“Because of the community that was built, because of the people who were awakened, there is a stronger pushback,” said Aneka Crisostomo, a sustainable transport advocate and community manager at Tambay Cycling Hub, a bike shop and gathering spot in Pasig, another city in Metro Manila.

“There are people who are now more vigilant about the road space we deserve, because a lot of us saw that it actually can be done.”

Many businesses are starting to see the value in catering to that growing community, said Makati Business Club’s Decena. Restaurants that earn a reputation for being “bike friendly” by treating bikers as valued customers rather than second-class citizens attract valuable word-of-mouth marketing among the cycling community. He also pointed to larger companies like McDonald’s and Robinsons, a mall chain, that have prioritized safe bike parking.

“The majority of our population, and therefore the majority of our market, is a cycling market,” he said. “If you’re a business, you stand to make more if you cater to the cyclists and pedestrians.”

Ultimately, Decena thinks it’s no big mystery what Metro Manila needs to do to maintain its cycling momentum and deliver a host of climate and health benefits to its citizens.

It doesn’t need to become Amsterdam, Paris, or even Bogotá, which Decena thinks is a more useful comparison than wealthy cities in the Global North. The city just needs its leaders to stick with the initiatives they started during the pandemic — to build out and maintain safe bike infrastructure rather than prioritizing cars at every turn.

“If you plan for transport based on your past patterns, you are always running the risk of replicating whatever patterns have held in the past,” he said. “So there has to come a point where you say, ‘We want to change what that looks like moving forward.’”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Can Manila’s cycling boom survive a return to car traffic? on Aug 24, 2023.

Conservative think tank The Heritage Foundation recently released a 920-page blueprint to drastically eliminate, or outright reverse, many of the climate change policies and laws put in place by the Biden administration, if a Republican wins the White House in 2024.

Titled Mandate for Leadership: The Conservative Promise, the document is a sprawling, aggressive work that sets the tone all across the government to deconstruct and remake the federal government, starting with the White House and spreading to all executive departments. While radical policy shifts like these have been common in history, what makes this one different is that, coming out so far ahead of the 2024 election, its goal is for a new Republican administration to hit the ground running from day one.

And when it comes to climate and energy, the proposals are alarming. In essence, the document – spearheaded by Paul Dans and Spencer Chretien, both veterans of the Trump administration – wraps the reversal of many of the current climate agenda goals of the Biden administration (and further back, to the remnants of policy from the Obama administration) in a cloak of energy security, resiliency, and fear.

“Ideologically driven government policies have thrust the United States into a new energy crisis” says the introduction to the section on the Department of Energy and Commissions. This chapter was written by Bernard L. McNamee, once the head of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) during the Trump administration. One of McNamee’s most notable controversies was being caught on video stating that there was an “organized propaganda war” being waged by leftists against fossil fuels, and prior to that, backing efforts to bail out the coal and nuclear industries when he was with the Department of Energy, an effort that failed.

“The new energy crisis is caused not by a lack of resources, but by extreme ‘green’ policies,” he writes, citing that taxpayer dollars are going towards “favored interests” like an electric grid, saying that, in a play straight out of Fear Politics, “government control of energy is control of people and the economy.”

As just one example, Project 2025 proposes to eliminate the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, stating that “taxpayer dollars should not be used to subsidize preferred businesses and energy resources, thereby distorting the market and undermining energy reliability.” If this office cannot be eliminated, then the blueprint suggests reorienting it to focus on things like “fundamental energy research, consistent with law” and further goes on to say that, for example, when it comes to energy efficiency standards for appliances, government should “limit regulatory overreach and protect against excessively stringent standards.”

Another example has to do with the grid, where the proposal states that renewables should not be expanded for the grid and improving the grid nationwide should focus on reliability and expansion. As for clean energy and the Office of Clean Energy Demonstration, which is an office dedicated to transitioning to a decarbonized energy system, the writers propose that “The next Administration should work with Congress to eliminate all DOE energy demonstration programs, including those in OCED. Taxpayer dollars should not be used to subsidize preferred businesses and energy resources, thereby distorting the market and undermining energy reliability.”

And what about the Inflation Reduction Act? Gut it, says Project 2025. Despite estimates from Climate Power, an environmental advocacy group, that more than 170,000 jobs have been created directly as a result of the IRA, Project 2025 says the only solution is to “support repeal” of the IRA, as well as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, laws passed that, according to McNamee, “are providing hundreds of billions of dollars in subsidies to renewable energy developers, their investors, and special interests.” He also calls for the end of government interference in “energy decisions,” ending the “war on oil and natural gas,” and to refocus FERC, where he was once director, to “ensuring that customers have affordable and reliable electricity, natural gas, and oil, and no longer allow it to favor special interests and progressive causes.”

Mandate for Leadership: The Conservative Promise concludes with a piece written by Edwin J. Feulner, once the president of The Heritage Foundation, and one of the leaders of conservative thought in the U.S. Feulner writes that after Donald Trump won the presidency in 2016, “the Administration had implemented 64 percent of its policy recommendations” which had been spelled out in its Mandate for Leadership that was developed before that election. These included tax cuts and cutting regulations, among other things. If a Republican wins the presidency in 2024 and begins to implement the Mandate for Leadership: The Conservative Promise, one of its first acts would be to “rein in the Environmental Protection Agency.”

The post Heritage Foundation Shows Plan to Decimate Biden’s Climate Progress, Cut the EPA if a Republican Wins 2024 Presidential Election appeared first on EcoWatch.

Workers at the shipping company UPS have just ratified a union contract that secures wage increases and extreme heat protections for more than 340,000 employees across the country. The deal marks a major win for what organizers have dubbed “hot labor summer,” in which labor fights led by groups ranging from auto workers to Hollywood actors have made headlines in recent months. UPS workers called attention in particular to the dangers posed by soaring temperatures and unsafe working conditions — a key issue in contract negotiations.

The five-year deal bumps up hourly wages for all employees, ends a two-tier wage system that allowed UPS to pay new drivers less, and eliminates mandatory overtime on drivers’ days off. UPS has also agreed to equip vehicles purchased after January 2024 with air conditioning and to retrofit existing cars with fans, vents, and exhaust heat shields. Leaders at the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, the union representing UPS workers, have called the contract “the most lucrative agreement the Teamsters have ever negotiated at UPS.”

“This contract will improve the lives of hundreds of thousands of workers,” said Sean O’Brien, president of the Teamsters union. “This is the template for how workers should be paid and protected nationwide, and nonunion companies like Amazon better pay attention.”

The deal was approved by 86.3 percent of unionized workers at UPS. Teamsters said that it received the highest number of votes ever seen for a Teamsters contract at UPS.

The new agreement highlights how extreme heat has raised the stakes for labor organizing this summer. Relentless heat and humidity in the South, a heat dome stifling the central U.S., and the hottest June and July recorded in world history have created especially dangerous conditions for workers. Heat-related health risks heighten exponentially for people who have to work outdoors or without air conditioning. In the past few months, workers from Greece to Texas have responded by staging walkouts, going on strike, and demanding greater heat protections for workers.

UPS drivers and warehouse workers say that record-breaking heat waves have rendered the company’s 12-hour workdays and unrealistic productivity benchmarks downright deadly. UPS previously refused to install air conditioning in delivery trucks, claiming that it wouldn’t be feasible due to their frequent stops. “When you open the bulkhead door to go to the back to look for packages, it’s like running into a brick wall — it’s so hot,” said Rick Johnson, a driver who has worked at UPS for 28 years, in a Teamsters video. “You can’t stay back there with the doors closed or you’ll pass out.”

In June 2022, a 24-year old UPS driver named Esteban Chavez died of heat-related heart failure while delivering packages in California. In August 2021, another driver named José Cruz Rodriguez died of heat-related illness on his delivery route in Texas. UPS has reported at least 143 heat-related injuries to the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration since 2015.

Union workers praised the contract for finally including vital protections for drivers working in sweltering conditions. “The A/C in the trucks is something I never thought I would see,” said Keith Short, a UPS worker who participated in the Teamsters strike at UPS in 1997, in a Teamsters video.

A tentative agreement reached between UPS and the Teamsters union last month averted what would have been the largest single-employer strike in U.S. history. UPS workers transport about $3.8 billion worth of goods each day, equal to about 5 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product, according to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

In addition to protecting workers from heat, the contract immediately bumps up all wages by $2.75 per hour, with total wage increases adding up to an additional $7.50 per hour over the next five years. All existing and new part-time employees will receive minimum wages of $21 per hour. The deal also guarantees union members will receive Martin Luther King Jr. Day as a full holiday for the first time, and creates thousands of new jobs during the length of the contract.

UPS called the contract a “win-win-win agreement” when the Teamsters first announced the tentative agreement last month. “This agreement continues to reward UPS’s full- and part-time employees with industry-leading pay and benefits while retaining the flexibility we need to stay competitive, serve our customers and keep our business strong,” the company said in a statement at the time.

The contract will go into effect as soon as one outstanding supplemental agreement for a local Teamsters chapter in Florida is renegotiated and ratified.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline UPS workers win wage increases, AC in new union contract on Aug 23, 2023.

During last year’s energy crisis, when prices soared due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Group of 20 (G20) nations provided $1.4 trillion to boost energy supplies and keep prices from climbing even higher, according to the thinktank International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD).

Financial support from the G20 was in the form of money borrowed from public financial institutions, subsidies and investments made by state-owned enterprises (SOEs), the IISD report, “Fanning the Flames: G20 provides record financial support for fossil fuels,” said. About one third of these funds were to back new fossil fuel projects.

According to the report, instead of subsidizing fossil fuels to reduce prices, prices need to be maintained at a level that reflects fossil fuels’ negative cost to society, in order to curb their use.

“This support perpetuates the world’s reliance on fossil fuels, paving the way for yet more energy crises due to market volatility and geopolitical security risks. It also severely limits the possibilities of achieving climate objectives set by the Paris Agreement by incentivizing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions while undermining the cost-competitiveness of clean energy,” the report said. “G20 governments need to shift their financial resources away from fossil fuels to instead provide targeted, sustainable support for social protection and the scaling-up of clean energy.”

Fossil fuel subsidies by the G20 in 2022 were more than four times those in 2021, mostly thanks to expanded support for consumers.

“The largest category of consumption subsidies was ‘price support’: governments fixing retail fossil fuel prices below the international market price. Below-market pricing was more common in G20 emerging economies, where it created large holes in government and SOE budgets, either due to direct spending or foregone revenue,” the report said.

An extra $1 trillion could be raised per year if an increased carbon tax of $25 to $75 for each ton of greenhouse gases was set, the IISD found, as reported by The Guardian.

“There is huge potential in subsidy reform,” said Richard Damania, a World Bank chief economist of a sustainability group, as The Guardian reported. “By repurposing wasteful subsidies, we can free up significant sums that could instead be used to address some of the planet’s most pressing challenges.”

France, Germany and Italy provided $213 billion in energy crisis support last year.

“Helping households and businesses during an energy crisis is understandable and necessary, but there are better ways to do it than subsidizing fossil fuels, which keeps consumers locked into emissions-intensive, polluting, and price-volatile energy sources,” the IISD report said.

IISD recommendations for G20 nations included setting a deadline for the elimination of fossil fuel subsidies. The Group of Seven most advanced economies in the world chose 2025, which the IISD said “is appropriate for all developed countries.”

The IISD also recommended ensuring that low-income workers, consumers and communities have “alternative welfare mechanisms” in place during the phasing out of fossil fuel subsidies, and that the G20 report on fossil fuel subsidies each year.

“The energy crisis has caused energy poverty and hardship, which have warranted strong government intervention. But fossil fuel subsidies are a notoriously inefficient way to help the poor and are perpetuating dependence on fossil fuels. Governments should instead provide social welfare through other mechanisms, like targeted welfare payments,” the report said. “Where such programs do not yet exist or cannot be implemented, energy subsidies should be targeted to the poor and vulnerable while governments incubate alternative clean energy technologies.”

The post G20 Nations Invested Record $1.4 Trillion Into Fossil Fuels in 2022, Report Says appeared first on EcoWatch.

Since late April, wildfires have been burning across Canada, blanketing the country and parts of the U.S. in unhealthy and sometimes dangerous smoke, in what Canadian wildfire officials have called the worst wildfire season ever recorded.

In a new study, scientists from the World Weather Attribution (WWA) Initiative examined the conditions that lead to the record series of wildfires and concluded that they were at least twice as probable due to human-caused climate change.

“In today’s climate, intense fire weather like that observed in May-July 2023 is a moderately extreme event, expected to occur once every 20-25 years. This means in any given year such an event is expected with 4-5% probability,” the study said. “Combining lines of evidence from the synthesis results of the past climate, results from historical and future projections and physical knowledge, we conclude that January-July cumulative DSR like that experienced in 2023 is at least seven times more likely to occur, and was 50% higher than it would have been without climate change; that peak fire weather intensity (FWI7x) like the 2023 event is at least twice as likely to occur, and around 20% more intense, than it would have been without human-induced climate change; and that this trend is projected to continue if warming continues.”

The study, “Climate change more than doubled the likelihood of extreme fire weather conditions in Eastern Canada,” was conducted by scientists from the Netherlands, Canada and the UK.

The area burned by this year’s wildfire season in Canada is bigger than Greece, reported The Guardian. More than 34 million acres have been burned — more than twice the previous record.

“The word ‘unprecedented’ doesn’t do justice to the severity of the wildfires in Canada this year. From a scientific perspective, the doubling of the previous burned area record is shocking. Climate change is greatly increasing the flammability of the fuel available for wildfires – this means that a single spark, regardless of its source, can rapidly turn into a blazing inferno,” said Yan Boulanger, a research scientist at Natural Resources Canada and part of the study team, as The Guardian reported.

For the study, the scientists used the fire weather index, which measures wildfire risk using a combination of temperature, humidity, rainfall and wind speed. The conditions caused by climate change like higher temperatures, low humidity and less snow cover primed regions across Canada to be more prone to fires by drying out vegetation.

“This year, high temperatures led to the rapid thawing and disappearance of snow during May, particularly in eastern Québec, resulting in unusually early wildfires,” said Philippe Gachon, a researcher at the Université du Québec à Montréal, as reported by The Guardian.

Friederike Otto, senior lecturer at the UK’s Grantham Institute and co-founder of WWA, said the influence of climate change on this year’s Canadian wildfire season may be even greater than the figures in the report demonstrate because the estimates used by the researchers were conservative, CNN reported.

“It’s becoming evident that the dry and warm conditions conducive to wildfires are becoming more common and more intense around the world as a result of climate change,” said Clair Barnes, a Grantham Institute research associate and one of the authors of the report, as reported by CNN.

Québec has had the most area affected by the wildfires with 12.8 million acres burned so far this year — approximately 26 times more than the average through late August.

The wildfires have not only affected the air quality in Canada, but in U.S. cities like New York, Minneapolis, Chicago and Seattle.

Hundreds of fires continue to burn across the country, with one-fifth of them in the Northwest Territories. Thousands of people were ordered to evacuate there last week, with thousands more being evacuated in British Columbia as wildfire smoke floated down into the Pacific Northwest.

“Until we stop burning fossil fuels, the number of wildfires will continue to increase, burning larger areas for longer periods of time,” Otto said, as The Guardian reported.

The post Canada’s Wildfires Made Twice as Likely by Human-Caused Climate Change, Study Finds appeared first on EcoWatch.

Visitor spending around national parks in the U.S. has reached a new high, according to the U.S. Department of the Interior. Visitors in 2022 spent $50.3 billion, supporting 378,400 jobs.

“At the Interior Department, we understand that nature is essential to the health, well-being and prosperity of every family and every community in America,” Secretary Deb Haaland said in a statement. “But outdoor recreation is not just good for the soul, it’s a significant driver of our national and local economies and job sustainability. When people visit one of our amazing parks, they are contributing to the community around them.”

The 2022 National Park Visitor Spending Effects report found that in addition to the nationwide economic benefits, more than 312 million visitors, a 5% increase from 2021, spent $23.9 billion (a 16% increase from the previous year) in the local communities near national parks, defined as local gateway regions within 60 miles of a national park.

While the $23.9 billion in visitor spending results in direct impacts to local businesses, it can also create indirect economic impacts as the businesses turn to other companies to reorder supplies and local employees spend their earnings within their communities, the report authors explained.

According to the report, the lodging industry had the highest direct impact of $9 billion in economic output, followed by restaurants with $4.6 billion in economic impact. In total, the $23.9 billion in spending contributed an estimated $17.5 billion in labor income, $29 billion in added value and $50.3 billion in economic output.

The report results are available as an interactive tool for those who want to see the breakdown of economic contributions by park, state or national economies and by industry sectors. According to the tool, the Great Smoky Mountains National Park had the highest visitor spending for 2022 at $2.1 billion.

“Since 1916, the National Park Service has been entrusted with the care of our national parks. With the help of volunteers and partners, we safeguard these special places and share their stories with more than 300 million visitors every year,” National Park Service Director Chuck Sams said in a statement. “The impact of tourism to national parks is undeniable: bringing jobs and revenue to communities in every state in the country and making national parks an essential driver to the national economy.”

The U.S. National Park System spans more than 85 million acres in 424 designated areas, and the National Park Service has monitored visitor spending and its economic impacts for more than three decades. The data can help provide more information for National Park Service leaders and policymakers as they make decisions regarding national parks.

The post National Park Visitor Spending Created Record High Economic Benefit in 2022 appeared first on EcoWatch.

Water harvesting involves the harvesting of rainwater, or water from the atmosphere through systems that involve collecting it for drinking and irrigation.

Rainwater harvesting is thousands of years old, and on a smaller practical scale, rainwater is a good way to conserve water for later use, particularly during dry seasons, and also saves money from using municipal water sources while protecting groundwater supply.

On a larger scale, it provides water for areas and communities dealing with water scarcity. Currently, areas all over the world are increasingly experiencing droughts. In 2022, 73% of the Western United States alone was in severe drought classification, while 31% was in extreme drought.

According to the United Nations World Water Development Report, 2 billion people globally also don’t have access to clean and safe drinking water, and scientists estimate that 4 billion people live in regions with severe fresh water shortages for at least one month each year, which may rise to between 4.8 billion and 5.7 billion by 2050 for reasons that include climate change, polluted water supplies and increased demand due to population growth.

Usage of rainwater harvesting has been increasing steadily. According to the global market, in 2020 $6 billion was spent on rainwater harvesting systems and is projected to increase by 4% by 2027.

Building systems can be simple or elaborate. This article will discuss rainwater catchment around the world, and how you can make it happen in your own backyard.

Waterproof cisterns thousands of years old are evidence of rainwater harvesting, for household use as well as dryland farming, in Asia, the Roman Empire and areas of the Middle East.

In India, archeological evidence of water conservation and harvesting was deeply rooted in the science of ancient India with many systems differing in its various regions to adapt to its uniqueness — some of which are still in use today.

One of the methods involved taankas. First built in the year 1607, they are a traditional rainwater harvesting method that involved an underground cistern that could store water for dry seasons to give to individual households or the community, or use for livestock. They vary in size and could hold anywhere from 1000 liters to 500,000 liters of water.

Indigenous cultures in the U.S. also created trenches that brought water naturally down from the mountain to the villages for drinking, crop irrigation and livestock.

Early settlers in North America also collected rainwater in barrels to do laundry and bathing. The water that was collected was more appreciated for its softness, and it was during this era that the phrase “hard water” would come about, which was groundwater and surface waters whose mineral content was too high to use.

Rainwater harvesting in some areas lost favor for awhile, but gained traction again in the 1950s, particularly in Australia, where roaded catchments were constructed to collect water for agricultural purposes.

Interest in research for water catchment for livestock also surged around this time in the U.S., and later in the 70s and 80s, for crop purposes in Africa.

There are several environmental benefits of rainwater harvesting.

When wastewater flows through sewer systems, it requires a lot of energy at treatment plants before being pumped back through the system into local waterways where it’s used again for any number of purposes, such as drinking water, irrigating crops and sustaining aquatic life.

The energy used to do this involves fossil fuels. Wastewater treatment plants may be responsible for emitting up to 23 percent more greenhouse gases because of fossil fuels used to treat detergent-laden water from residential showers, household washing machines and industrial sites. So when you harvest and use rainwater, you’re helping to save energy and reduce carbon emissions.

Collecting rainwater for use in the garden will allow you to release it into your garden later when the ground is not saturated, to recharge groundwater supplies to continue to hydrate the soil.

Rainwater is great for plants, because it’s free of chemicals and salts that are in treated water, and can alter the chemical composition of the soil (and also end up with what you consume when you eat plants). Rainwater also has a balanced pH that is required by plants.

Collecting rainwater reduces the amount of runoff water that collects pesticides and other chemicals, and relieves sewer systems, which could overflow in areas that cannot handle the volume of runoff, which helps avoid contamination of the ground.

Water reservoirs and groundwater are usually overdrawn, particular in urban areas where there isn’t as much surface area to absorb water.

Rainwater harvesting can have a number of applications and can be from simple to elaborate.

A simple rainwater harvesting system where pipes run from rain gutters into a rain barrel or tank is known as a “dry system” because they don’t hold any water in the pipes after rain ceases. They also do not create breeding grounds for insects.

“Wet Systems” are used when pipes can’t run directly into tanks, which may be located far away from the collection surface, or where a series of tanks services a number of areas. These systems, where pipes go underground, can utilize a pressurized system to avoid retaining stagnant water, and can be mosquito-proofed through screens and filters.

Since rainwater collects dust and pollutants through the atmosphere, and collects contaminants where it lands on the surface, rainwater collected from unclean surface runoffs isn’t suitable for drinking water and needs to be purified.

As mentioned above, throughout history rainwater harvesting has been used by households for drinking water, watering the garden, laundry and other uses.

Residential rain collection can be caught from the roof or the ground. Roof catchment systems collect water from its surface and route it through a system of gutters and pipes into a rain barrel, usually located on the ground level.

Choice of roofing material for this is important since some types of material, like those with coatings or metallic finishes or asphalt, could contaminate water. It’s better to use aluminum, tiles, slate or corrugated iron roofs.

A ground residential rainwater collection system collects water via drain pipes or earthen dams and stored above or below ground in tanks. The quality of water may be lower at the ground level, rendering the captured water suitable for landscaping needs only.

Costs for systems can vary. An inexpensive DIY system could run around $200 with a 55-gallon barrel, or up to $20,000 for a more complex roof catchment.

Rainwater harvesting is a great way to sustainably irrigate crop fields. It also serves as a form of damage control by diverting heavy rainfall from damaging crops.

As America’s cities struggle with water supply shortages and runoff pollution problems, capturing rainwater from rooftops provides a solution to increase water supply and improve water quality, according to a recent analysis on “Capturing Rainwater from Rooftops” by the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC).

Using rainwater catchment in urban areas also reduces one’s dependence on municipal water, which is the tap that gets treated and rerouted through pipes underground to your faucet. This lowers bills, and also reduces the carbon footprint used by the water treatment facilities before it reaches your home or business.

Some places in cities use blue roof systems which detain stormwater to mitigate flooding.

Large-scale rainwater catchment systems on buildings can lower utility costs and provide water for flushing toilets, irrigation for landscaping, fire suppression, manufacturing processes, vehicle washes, laundries and filling pools.

Rainfall is not always dependable, particularly in arid regions that undergo long drought and dry seasons.

It requires regular maintenance as systems are prone to rodents, mosquitoes, algae growth, insects and lizards which can contaminate the harvested rainwater.

Setup costs for the rainwater harvesting system are high.

Several initiatives around the world utilize rainwater harvesting to provide water for communities in need.

One of them is the Global Rainwater Harvesting Collective, a project of the UN’s Department of Economic and Social Affairs. It helps provide drinking water to schools facing shortages and utilizes rooftop catchment systems on schools.

In India, NGO One Prosper provides families with filters and water harvesting systems in the Thar Desert, where many people, particularly young girls, spend up to seven hours a day trying to retrieve water from far outside of town to bring back for use, which detracts from their education. They also provide families with seeds and farm training so they can grow their own food, and build farming dykes so they can leverage rainwater to irrigate and double crop yields for those who grow millet for income.

California-based Save the Rain also provides systems at homes and at schools on several different continents where water scarcity is an issue, particularly in Tanzania. To date they have installed systems on 4710 homes, and at 365 schools. The group said that 80% of children were walking for water instead of going to school, but with these systems, schools retain up to 95% retention rates.

There are also several initiatives in Mexico such as Isla Urbana, which installs systems in communities that lack access to water.

Founded in Texas in 1994, the American Rainwater Catchment Systems Association was created to renew attention to rainwater harvesting, and whose goal is to promote a favorable regulatory atmosphere, creating a resource pool and educating professionals and the general public regarding safe rainwater design, installation and maintenance practices.

Much like a household dehumidifier can pull moisture from air to keep things from getting moldy, the same process can pull water from the atmosphere to create potable water.

While the market is relatively small right now, the technology has been around for decades. Several companies have sold and sent devices to drought-stricken regions for disaster relief and to replace contaminated drinking water.

While there are larger for-profit enterprises, one of the more grassroots is public charity the Moses West Foundation which has been providing atmospheric water generators during crises like in Flint and Mississippi and other disenfranchised areas with water issues. Since the foundation’s inception they’ve provided 4.5 million liters of clean water.

Much of the technology that’s used differs from dehumidifiers in that water quality controls are built into the machine.

Another atmospheric water harvesting technology, hydropanels, utilizes desiccants, which are materials that soak up moisture (some are found in silica gel and baby nappies).

California-based company Water Harvesting is also developing devices that range from small kitchen countertop harvester for households to large scale industrial use for village communities.

Swedish company Drupps has built machines that harvest water from waste steam from industrial chimneys and turns it into drinkable water. According to their website, their process uses latent heat from the steam to power atmospheric water generation, while reducing energy use and carbon dioxide emissions in drying processes.

Another angle of this technology, fog harvesters, have been around for decades in regions subject to water scarcity and fog. The process uses vertical mesh nets to induce the fog-droplets to fall down into a trough.

Globally, policies and incentives have grown over the years to mandate rainwater harvesting systems.

India has seen many mandates and reforms with rainwater harvesting systems. In New Delhi, the Ministry of Urban Development has made rainwater harvesting mandatory in all new buildings with a roof area of more than 100 square meters and in all plots with an area of more than 1000 square meters that are being developed.

The Central Ground Water Authority (CGWA) has made rainwater harvesting mandatory in all institutions and residential colonies in notified areas (South and South-west Delhi and adjoining areas such as Faridabad, Gurgaon and Ghaziabad). This is also applicable to all the buildings in notified areas that have tube wells. CGWA has also banned drilling of tube wells in notified areas.

Tamil Nadu also became the first Indian state to make the practice mandatory in every building, to avoid groundwater depletion.

The governments of Cambodia, Haiti, China, Thailand and Brazil have all deployed rainwater harvesting systems for households and industries.

In 2003, a public-private partnership called “1 Million Cisterns” in Brazil aimed at providing 1 million households located in drought-prone parts of the South American country with easy-to-access harvested rainwater. So far the program has benefited 628,355 families.

In the U.S., the top five states for rainwater harvesting with government incentives and rebates are Texas, California, Arizona, Iowa and Illinois.

Various regulations include some states requiring permits and code compliance, limiting how much water is captured, and requiring nonpotable usage only.

Colorado had a longtime ban on home rainwater harvesting over the concern that household rain barrels would take water from the supply available to agriculture and other water rights holders. That ban was lifted in 2016, but now there are other strong regulations.

A guide to regulations by state can be found here.

There are many environmental and health benefits to water harvesting, especially as a means to provide water to communities affected by water scarcity, water contamination and/or natural disasters. While there are some drawbacks, particularly with the cost of installation, several governments and private agencies offer incentives to help install systems.

In some areas of the world, initiatives are not only providing rainwater harvesting systems, but also using them as a starting point to revive and empower communities through more jobs and food security.

The post Water Harvesting 101: Everything You Need to Know appeared first on EcoWatch.

The swarms were so thick they obscured the sun. Mohammed Adan, a farmer in northeastern Kenya, watched the horde of desert locusts first descend in late 2019. He’s been grappling with their legacy ever since.

Adan and 61 other farmers grow tomatoes, mangoes, watermelon, and other crops on Taleh Farm, a 309-acre property outside Garissa, a remote town not far from the Somali border. When the locusts first touched down, Garissa’s villagers resorted to traditional mitigation methods like drumming and banging pots and pans together — anything to make loud noise that might disperse the swarm. Women and children shouted at the descending crush, but their endeavors were largely fruitless.

Billions of ravenous, short-horned grasshoppers alighted, devouring every bit of living plant matter in their path. Between February and June 2020, Taleh Farm was eaten to the ground. Adan’s son, Abubakar Mohamed, who goes by Abu, estimated that the locusts caused $2,000 worth of damage that season — a devastating sum in an area where the average annual salary is below $300.

“We’ve heard about locusts from our fathers and grandfathers,” Adan, who is in his mid-50s, recalled. “But we’ve never had to deal with anything like this ourselves.”

While locust swarms spread across 10 countries over the course of early 2020, Kenya was particularly hard hit — one of the swarms feeding off the country stretched to three times the size of New York City. Three million people across the country, many of them small-scale farmers, were at risk of losing their entire season’s harvest. A legion of international organizations, including the United Nations’ World Food Programme and Food and Agriculture Organization, or FAO, marshaled support in collaboration with Kenya’s Ministry of Agriculture. Throughout the locust invasion, the FAO raised more than $230 million, which allowed it to acquire 155,600 liters of synthetic pesticides that were used to treat nearly 500,000 acres.

To handle ground-spraying operations, the Kenyan government enlisted both its army as well as members of the National Youth Service, a voluntary, government-funded vocational and training organization for young Kenyans. Meanwhile, the FAO contracted charter airline companies to conduct aerial spraying. An issue of apocalyptic scale required all hands on deck.

Farmers like Adan were relieved that the government and aid organizations were stepping in to help. “We wanted those pesticides,” he told Grist. “Otherwise, we would have lost everything.”

But Adan didn’t know at the time that the FAO and other humanitarian groups had procured pesticides that were either already banned in the U.S. and Europe or soon would be. The synthetic pesticides in question — part of a chemical class known as organophosphates that includes chlorpyrifos, fenitrothion, malathion, and fipronil — have been known to cause dizziness, nausea, vomiting, watery eyes, and loss of appetite in humans who come into contact with them. Long-term exposure has been linked to cognitive impairment, psychiatric disorders, and infertility in men.

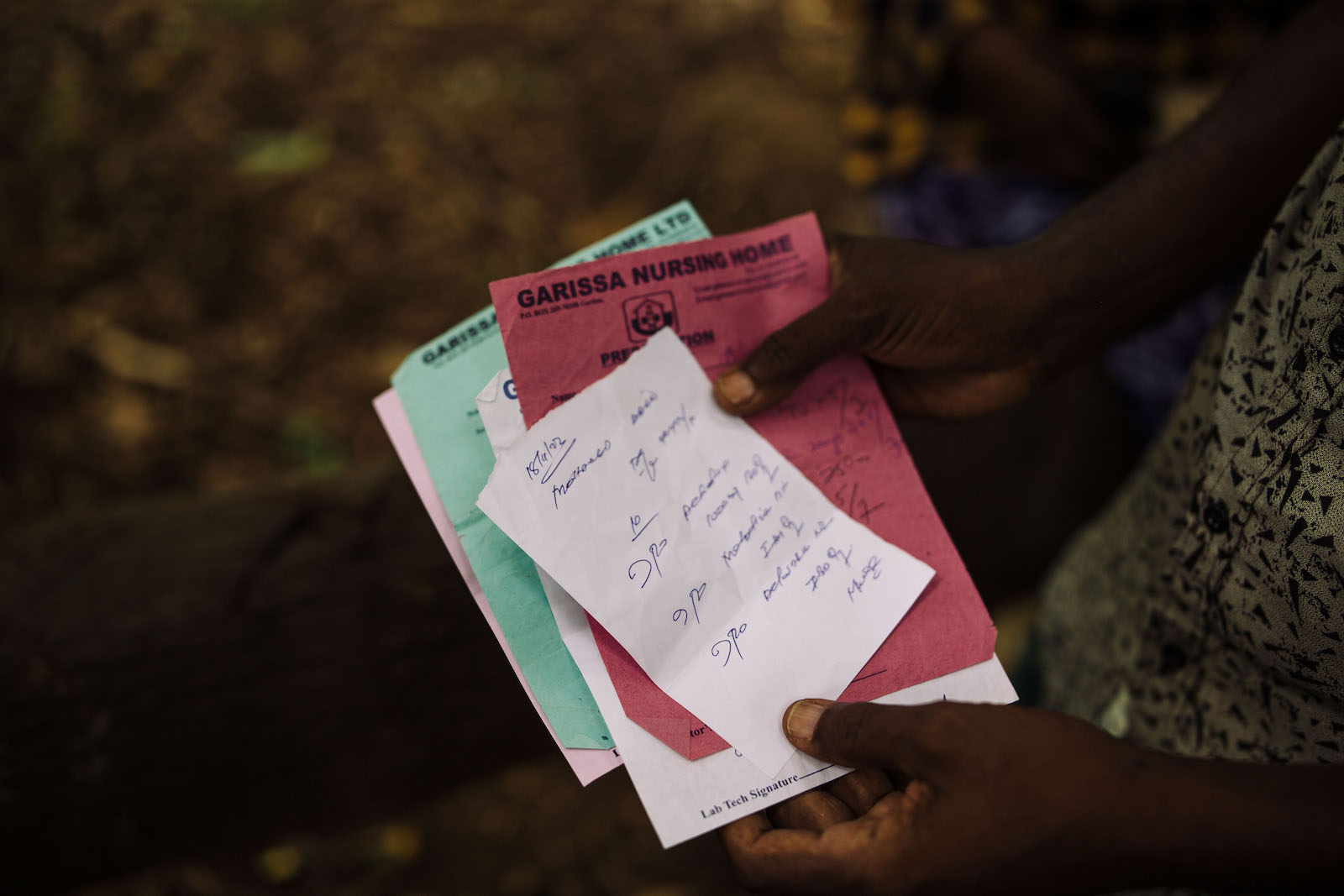

Subsistence farmers in Garissa believe they were accidentally poisoned while using these chemicals — and they’re still dealing with the ramifications. Adan has been suffering from a host of health maladies since 2020, including infertility and incontinence, and he has undergone five surgeries in the last few years.

Internal FAO documents show that the agency was aware of widespread environmental and public health problems that resulted from its distribution of pesticides. The agency’s own assessment found that the toxic chemicals were handed to farmers without any protective equipment, such as gloves and coveralls, or adequate training on how to use them safely. Christian Pantenius, a former FAO staff member who worked as an independent expert adviser to help the agency coordinate its 2020 spraying campaign in Kenya and Ethiopia, said he saw hundreds of FAO-recruited National Youth Service members handling toxic chemicals in northern Kenya without sufficient training or protective equipment.

“I was shocked,” he told Grist. “I was furious about it. Can you imagine this happening in Europe?”

In April 2020, at the height of the locust upsurge, the Taleh farmers attended an emergency training hosted by staff of the Ministry of Agriculture’s Garissa County office. During an informal three-day demonstration, Adan said they were briefed on pesticide-spraying techniques. (Ahmed Sirat, a retired agricultural extension officer who worked with the Taleh farmers at the time, confirmed the training took place.)

After receiving their allotted chemicals, the farmers set off to salvage their crops. Adan said they were warned during the training that the pesticides are dangerous to humans, but they were not provided with specific chemical profiles or protective equipment.

The farmers burned through the first round of pesticides within a matter of days. This fenitrothion-heavy batch came in 500-milliliter bottles, which Sirat had shown them how to mix with water. Fenitrothion is an inexpensive, hazardous pesticide widely used in countries like Brazil, Japan, and Australia. However, it has not been approved for use in the U.S. because it can cause nausea, dizziness, and confusion at low exposures — and respiratory paralysis and even death at high exposures. The pesticide was so strong that some of the locusts died upon contact, falling right off the fruit trees. Clearly, the chemicals were working. But the farmers needed more.

On behalf of his farming committee, Adan requested more pesticides from the county agricultural extension officers. This time, they came in 20-liter cans. “There was a picture of an airplane on the can,” Adan recalled. In retrospect, he believes they were given chemicals meant for aerial spraying, rather than ground operations.

The farmers agreed to spray as a team, moving in sync. Adan remembers crouching as he mixed the chemicals with water, as instructed. He then poured the pesticide into a knapsack sprayer, a device consisting of a pressurized container that disperses liquid through a hand-held nozzle. As he was preparing to hoist the sprayer on his back, Adan accidentally hit the nozzle, spilling its contents across his stomach and back and down his groin and legs. He didn’t think much of it; the immediacy of the locust hordes captured his full attention. Adan repeated the operation and only washed the chemical off his body with water after attending to his crops.

The farmers’ efforts eventually paid off. They were able to protect some of their crops and sold them after harvest. But the farmers have since been suffering from a range of health effects that they attribute to pesticide exposure. For months after spilling chemicals on himself, Adan felt sick. A year later, in April 2021, the malaise culminated in an inability to pass urine. His muscles grew weak, and he often found himself easily fatigued.

Hussein Abdi and Adan Hussein Yusuf, who also work on Taleh Farm, were exposed to milky clouds of the pesticide when they were spraying their mango trees in 2020. The chemicals irritated their eyes, and both farmers have since had eye surgeries at hospitals in Garissa. Abdi still struggles with light sensitivity and wears shades nearly all the time, even on overcast days.

In response to Grist’s questions about the Taleh farmers’ health issues, Garissa County officials denied issuing pesticides to farmers. Ben Gachiri, an officer with the Garissa County communications office, said that it was “impossible that the farmers could have been instructed to do this themselves.” In a written statement, he claimed that no farmer or volunteer was ever issued locust-control pesticides or lodged complaints about pesticide exposure.

The FAO’s assessment, however, tells a different story.

Massive locust surges have threatened farmers throughout the ages, but the swarms have been escalating in recent decades. Desert locust outbreaks require the perfect brew of weather, moist soil, and vegetation conditions. Researchers have found that increases in temperature and rainfall in desert regions, as well as high wind speeds during tropical cyclones, create an ideal environment for locusts to breed and migrate. The fact that many of these conditions have been amplified by climate change has only made locust outbreaks more likely.

The FAO has supported synthetic pesticides as the primary method of locust control since their popularization in the 1980s. A 2021 analysis of FAO pesticide purchase data by the environmental news website Mongabay found that more than 95 percent of the pesticides the agency delivered to East African nations during the locust outbreaks were proven to cause harm to humans and animals. Chlorpyrifos, which the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency had already determined to have no safe level of exposure, made up more than half of the haul. (Scientific evidence linking chlorpyrifos to a slew of neurodevelopmental harms ultimately led the U.S. agency to ban its domestic use in 2021.)

The FAO is well aware of the harmful health effects of chlorpyrifos and other organophosphate pesticides, which it categorizes as “extremely hazardous.” According to an internal 2020 FAO report, which Grist obtained through an officer at Kenya’s Ministry of Agriculture, FAO staff and consultants observed spray sites across 18 counties in Kenya from July to September of that year. (The FAO has not replied to queries about why the document is not publicly available.)

The report found the agency failed to conduct a full environmental and social impact assessment as required under Kenya’s environmental laws, given the state of emergency produced by the massive locust outbreak. Most of the decisions made with regard to locust mitigation efforts remained opaque to the communities most affected, who received little to no guidance on the pesticides’ toxicity and were not briefed on their health or environmental effects. At several operation sites in Kenya’s far north, “communities complained of lack of information and communication” during locust control operations within their vicinity, the report noted.

In Samburu County, northwest of Garissa in Kenya’s Great Rift Valley, FAO monitoring found that “non-trained personnel” took the lead on ground-spraying operations, leading to rampant user errors. The Locust Pesticide Referee Group, an independent body of experts that advises the FAO on pesticide use, recommends that knapsack-sprayers distribute 1 liter per hectare of land, which is roughly 0.11 gallons per acre. But the report noted that the untrained volunteers had sprayed about 3.63 gallons per acre — more than 30 times the recommended amount — on a rainy day when pesticides are likely to run off and pollute soil and water sources.

In Lodwar, northwestern Kenya’s largest town, the FAO had trained a crew of 106 National Youth Service members on pesticide management and safety. Still, some crew members “complained of itchiness on skin during spraying,” the report noted. FAO monitoring staff noted that young children were seen playing next to carelessly disposed gloves, masks, gumboots, overalls, safety goggles, and uncollected pesticide drums.

The scathing report found that farmers and community members weren’t properly informed about when spraying occurred, how long it would last, or what the chemicals’ effects were on human and animal health. As a result, around Oldonyiro, a heavily sprayed area in Isiolo County a few hundred miles northwest of Garissa, local Ministry of Agriculture authorities did not collect accounts of cow, camel, and goat mortalities that came from community members.

Less harmful alternatives to synthetic pesticides exist and have proven their efficacy, but they are not yet in widespread global use. Biopesticides developed from Metarhizium acridum fungal spores were first tested in 1989 under a private research program, after a particularly vicious three-year locust plague in East Africa. After years of painstaking testing, a commercial product finally hit the market in 2005. The FAO first used a version of the biopesticide on an operational scale in Tanzania in 2009, and later in Madagascar and Central Asia.

In 2020, Metarhizium-derived biopesticides were used on a large scale with great success in Somalia. The effectiveness was comparable to that of synthetic pesticides: 60 percent mortality after 10 days, increasing to 83 percent after 14 days. Though biopesticides have a higher initial cost than synthetics, researchers found that this was quickly offset by low environmental damage and the elimination of disposal costs. As a bonus, biopesticides can boost honey production, a common livelihood in East Africa, since they are far gentler on pollinators than synthetic chemicals.

Despite their proven track record, companies have largely been unwilling to invest in such biopesticides. That’s because the products are highly targeted and cannot be used on as wide a range of pests. And because they are derived from nature, producing identical batches has proven tricky.

“Economically it’s not as viable, and therefore not of interest to governments –– or companies,” said Pantenius.

FAO representatives declined to speak directly with Grist about the agency’s pesticide procurement procedure, or to elaborate on how decisions were made concerning its locust campaign in Kenya. To this day, the FAO has declined to publicly release reports about documented user error and exactly how much of each pesticide was sprayed.

But in an emailed statement from the FAO’s East Africa regional office, the agency emphasized that it was up to individual countries to select which pesticides they would authorize for use, and that locust control measures were “closely monitored to minimize risks to people and communities.” The FAO denied that farmers or any other untrained community members participated in spraying. The statement added that the FAO encouraged countries to use biopesticides, but that limited production of these alternatives made them insufficient for the scale of the outbreak.

Pantenius said that the FAO has worked to protect crops from being devoured by locusts in cost-effective ways while also considering environmental damage. However, he believes that it and other international humanitarian organizations must put more pressure on governments to make better-informed decisions. “It’s time that we get to a point where we draw a line and say, ‘We’re willing to help you, but won’t provide chemical pesticides,’” he said.

“By the time locusts cross over the crops, it’s already too late [to consider alternatives],” Pantenius added. “Once the plague is over, everyone quickly moves on to more pressing issues.”

Three years after the locusts first arrived, Adan has realized that he could be dealing with effects from pesticide exposure for the rest of his life.

“I’m a lot better now, but it still hurts to stand up,” he explained, lightly pounding the muscles around his thighs. Until recently, he had also been struggling with incontinence.

To date, Adan has undergone five surgeries, inserting and removing catheters, in an attempt to address a series of urinary tract complications from the accident. He estimates that the hospital bills have racked up to nearly $10,000 — he was forced to sell 14 camels at approximately $400 each to help cover the costs, and neighbors and relatives pitched in.

Adan’s infertility — a known ramification from exposure to synthetic organophosphates such as chlorpyrifos — has been an even greater blow, given local cultural expectations. “When one stops procreating, one’s life is effectively over,” his son Abu explained.

As of early this year, Adan’s health had deteriorated. He started having trouble passing urine again and may need a sixth surgery. Abu said that they are considering applying for a medical visa to India, with the hopes that overseas expertise might solve his lingering urinary tract issue.

On a sweltering day under the equatorial sun late last November, Adan stood beneath the shade of overgrown mango trees with his friends Abdi and Yusuf. He recalled a local saying about locusts, revealing the enduring nuisance that the pests have been in the region — existing as mere folklore for some generations, a living nightmare for others.

“Anyone, even a cow, who eats too much, you’re said to be eating like an ayah — a locust.”

Adan remains concerned about future outbreaks. If a better preparedness plan is not put in place, “It will cause more damage than this,” he said. “This is something that comes with God’s plan — that can’t be predicted by a human being.”

Anthony Langat contributed reporting to this story.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How a UN-led fight against locusts took a toxic toll on Kenyan farmers on Aug 23, 2023.