What connects us all? Nature and our shared relationships through nature. Print or share We…

The post We Earthlings: Yeah, I’m In To Cook Organic appeared first on Earth911.

What connects us all? Nature and our shared relationships through nature. Print or share We…

The post We Earthlings: Yeah, I’m In To Cook Organic appeared first on Earth911.

Allie “Nokko” Johnson is a member of the Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana, and they love teaching young tribal members about recycling. Johnson helps them make Christmas ornaments out of things that were going to be thrown away, or melts down small crayons to make bigger ones.

“In its own way, recycling is a form of decolonization for tribal members,” Johnson said. “We have to decolonize our present to make a better future for tomorrow.“

The Coushatta Reservation, in southern Louisiana, is small, made up of about 300 tribal members, and rural — the nearest Walmart is 40 minutes away. Recycling hasn’t been popular in the area, but as the risks from climate change have grown, so has the tribe’s interest. In 2014, the tribe took action and started gathering materials from tribal offices and departments, created recycling competitions for the community, and started teaching kids about recycling.

Recently, federal grant money has been made available to tribes to help start and grow recycling programs. Last fall, the Coushatta received $565,000 from the Environmental Protection Agency for its small operation. The funds helped repair a storage shed, build a facility for the community to use, and continue educational outreach. But it’s not enough to serve the area’s 3,000 residents of Native and non-Native recyclers for the long haul.

Typically, small tribes don’t have the resources to run recycling programs because the operations have to be financially successful. Federal funding can offset heavy equipment costs and some labor, but educating people on how to recycle, coupled with long distances from processing facilities, make operation difficult.

But that hasn’t deterred the Coushatta Tribe.

In 2021, the European Union banned single-use plastics like straws, bottles, cutlery, and shopping bags. Germany recycles 69 percent of its municipal waste thanks to laws that enforce recycling habits. South Korea enforces strict fees for violations of the nation’s recycling protocols and even offers rewards to report violators, resulting in a 60 percent recycling and composting rate.

But those figures don’t truly illuminate the scale of the world’s recycling product. Around 8.3 billion metric tons of plastic have been manufactured since the 1950’s and researchers estimate that 91 percent of it isn’t recycled. In the United States, the Department of Energy finds that only 5 percent is recycled, while aluminum, used in packaging has a recycling rate of about 35 percent. The recycling rate for paper products, including books, mail, containers, and packaging, is about 68 percent.

There are no nationwide recycling laws in the U.S., leaving the task up to states, and only a handful of states take it seriously: Ten have “bottle bills,” which allow individuals to redeem empty containers for cash, while Maine, California, Colorado, and Oregon have passed laws that hold corporations and manufacturers accountable for wasteful packaging by requiring them to help pay for recycling efforts. In the 1960s, the U.S. recycling rate across all materials — including plastic, paper, and glass — was only 7 percent. Now, it’s 32 percent. The EPA aims to increase that number to 50 percent nationwide by 2030, but other than one law targeted at rural recycling moving through Congress, there are no overarching national recycling requirements to help make that happen.

In 2021, Louisiana had a recycling rate of 2.9 percent, save for cities like New Orleans, where containers are available for free for residents to use to recycle everything from glass bottles to electronics to Mardi Gras beads. In rural areas, access to recycling facilities is scarce if it exists at all, leaving it up to local communities or tribal governments to provide it. There is little reliable data on how many tribes operate recycling programs.

“Tribal members see the state of the world presently, and they want to make a change,” said Skylar Bourque, who works on the tribe’s recycling program. “Ultimately, as a tribe, it’s up to us to give them the tools to do that.”

But the number one issue facing small programs is still funding. Cody Marshall, chief system optimization officer for The Recycling Partnership, a nonprofit, said that many rural communities and tribal nations across the country would be happy to recycle more if they had the funds to do so, but running a recycling program is more expensive than using the landfill that might be next door.

“Many landfills are in rural areas and many of the processing sites that manage recyclables are in urban areas, and the driving costs alone can sometimes be what makes a recycling program unfeasible,” he said.

The Recycling Partnership also provides grants for tribes and other communities to help with the cost of recycling. The EPA received 91 applications and selected 59 tribal recycling programs at various stages of development for this year, including one run by the Muscogee (Creek) Nation in Oklahoma, which began its recycling program in 2010. Today, it collects nearly 50 metric tons of material a year — material that would have otherwise ended up in a landfill.

“Once you start small, you can get people on board with you,” said James Williams, director of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s Environmental Services. He is optimistic about the future of recycling in tribal communities. “Now I see blue bins all through the nation,” he said, referring to the recycling containers used by tribal citizens.

Williams’ department has cleaned up a dozen open dumps in the last two years, as well as two lagoons — an issue on tribal lands in Oklahoma and beyond. Illegal dumping can be a symptom of lack of resources due to waste management being historically underfunded. Those dumping on tribal land have also faced inadequate consequences.

“We still have the issue of illegal dumping on rural roads,” he said, adding that his goal is to clean up as many as possible. “If you dump something, it’s going to hit a waterway.”

According to Williams, tribes in Oklahoma with recycling programs work together to address problems like long-distance transportation of materials and how to serve tribal communities in rural areas, as well as funding issues specific to tribes, like putting together grant applications and getting tribal governments to make recycling a priority. The Choctaw Nation in Oklahoma also partners with Durant, a nearby town. Durant couldn’t afford a recycling program of their own, so they directed recycling needs to the tribe.

This year’s EPA grant to the Muscogee program purchases a $225,000 semitruck, an $80,000 truck for cardboard boxes, and a $200,000 truck that shreds documents. Muscogee was also able to purchase a $70,000 horizontal compactor, which helps with squishing down materials to help store them, and two $5,000 trailers for hauling. Williams’ recycling program operates in conjunction with the Muscogee solid waste program, so they share some of their resources.

Returns on recycled material aren’t high. In California, for instance, one ton of plastic can fetch $167, while aluminum can go for $1,230. Corrugated cardboard can also vary wildly from $20 to $210 a ton. Prices for all recycled materials fluctuate regularly, and unless you’re dealing in huge amounts, the business can be hard. Those who can’t sell their material might have to sit on it until they can find a buyer, or throw it away.

Last year, Muscogee Creek made about $100,000 reselling the materials it collected, but the program cost $250,000 to run. The difference is made up by profits from the Muscogee Creek Nation’s casino, which helps keep the recycling program free for the 101,252 tribal members who live on the reservation. The profits also help non-Natives who want to recycle.

The Coushatta Tribe serves 3,000 people, Native and non-Native, and they have been rejected by 12 different recycling brokers – individuals that act as intermediaries between operations and buyers – due to the distance materials would have to travel.

Allie Johnson said she couldn’t find a broker that was close enough, or that was willing to travel to the Coushatta Tribe to pick up their recycling. “We either bite the cost,” she said, “or commute and have to pay extra in gas. It’s exhausting.”

Currently, the only place near them that’s buying recyclables is St. Landry Parish Recycling Center, which only pays $0.01 per pound of cardboard. A truck bed full of aluminum cans only yields $20 from the nearest center, 90 minutes away. That’s how much the tribe expects to make for now.

Still, the Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana is not giving up.

With this new injection of federal money, they will eventually be able to store more materials, and hopefully, make money back on their communities’ recyclables. Much like the Muscogee Creek Nation, they see the recycling program as an amenity, but they still have hopes to turn it into a thriving business.

In the meantime, the Coushatta keep up their educational programming, teaching children the value of taking care of the Earth, even when it’s hard.

“It’s about maintaining the land,” Johnson said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Recycling isn’t easy. The Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana is doing it anyway. on May 28, 2024.

If you need an inhaler, the chances are good you think about that little device…

The post How To Recycle Inhalers appeared first on Earth911.

For the first time, a NASA satellite has been launched with the purpose of improving the ability to predict climate change by measuring the heat that escapes from Earth’s poles.

The satellite — the first of a pair — is in orbit following lift-off from Rocket Lab’s Electron rocket in Māhia, New Zealand, on Saturday, a press release from NASA said.

“This new information — and we’ve never had it before — will improve our ability to model what’s happening in the poles, what’s happening in climate,” said Karen St. Germain, Earth sciences research director at NASA, as AFP reported.

The two cube satellites in NASA’s Polar Radiant Energy in the Far-InfraRed Experiment (PREFIRE) mission — called CubeSats — are each the size of a shoebox, the press release said. They will measure how much heat our planet radiates from two of its coldest and most remote regions.

Technicians integrate NASA’s PREFIRE payload inside the Rocket Lab Electron rocket payload fairing on May 15, 2024. Rocket Lab / NASA Kennedy Space Center

St. Germain explained that, since small satellites answer precise scientific questions, they can be seen as “specialists,” while larger satellites are “generalists,” reported AFP.

“NASA needs both,” St. Germain said.

DATA from the mission will assist researchers in better predicting how Earth’s weather, seas and ice will change as the planet warms, the press release said.

“NASA’s innovative PREFIRE mission will fill a gap in our understanding of the Earth system – providing our scientists a detailed picture of how Earth’s polar regions influence how much energy our planet absorbs and releases,” St. Germain said in the press release. “This will improve prediction of sea ice loss, ice sheet melt, and sea level rise, creating a better understanding of how our planet’s system will change in the coming years — crucial information to farmers tracking changes in weather and water, fishing fleets working in changing seas, and coastal communities building resilience.”

Communications have been successfully established with the satellite by ground controllers. After the other CubeSat is launched, scientists and engineers will conduct a 30-day period of checks to ensure both PREFIRE satellites are working properly, after which they are expected to be in operation for 10 months.

“At the heart of the PREFIRE mission is Earth’s energy budget – the balance between incoming heat energy from the Sun and the outgoing heat given off by the planet. The difference between the two is what determines the planet’s temperature and climate. A lot of the heat radiated from the Arctic and Antarctica is emitted as far-infrared radiation, but there is currently no detailed measurement of this type of energy,” the press release said.

The atmosphere’s water vapor content — combined with the presence, composition and structure of clouds — influences how much far-infrared radiation escapes from the poles.

“This is critical because it actually helps to balance the excess heat that’s received in the tropical regions and really regulate the earth’s temperature,” said Tristan L’Ecuyer, principal investigator for PREFIRE and a researcher at University of Wisconsin, Madison, as AFP reported. “And the process of getting the heat from the tropical regions to the polar regions is actually what drives all of our weather around the planet.”

PREFIRE data will allow researchers to locate when and where far-infrared energy is radiating from the Antarctic and Arctic environments into space, the press release said.

“The PREFIRE CubeSats may be small, but they’re going to close a big gap in our knowledge about Earth’s energy budget,” said Laurie Leshin, director of Southern California’s NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in the press release.

Each of the satellites carries a thermal infrared spectrometer — an instrument which uses specially shaped sensors and mirrors to measure infrared wavelengths.

“Our planet is changing quickly, and in places like the Arctic, in ways that people have never experienced before,” L’Ecuyer said in the press release. “NASA’s PREFIRE will give us new measurements of the far-infrared wavelengths being emitted from Earth’s poles, which we can use to improve climate and weather models and help people around the world deal with the consequences of climate change.”

The post NASA Launches Satellite to Predict Climate Change by Studying Earth’s Poles appeared first on EcoWatch.

Can metals that naturally occur in seawater be mined, and can they be mined sustainably? A company in Oakland, California, says yes. And not only is it extracting magnesium from ocean water — and from waste brine generated by industry — it is doing it in a carbon-neutral way. Magrathea Metals has produced small amounts of magnesium in pilot projects, and with financial support from the U.S. Defense Department, it is building a larger-scale facility to produce hundreds of tons of the metal over two to four years. By 2028, it says it plans to be operating a facility that will annually produce more than 10,000 tons.

Magnesium is far lighter and stronger than steel, and it’s critical to the aircraft, automobile, steel, and defense industries, which is why the government has bankrolled the venture. Right now, China produces about 85 percent of the world’s magnesium in a dirty, carbon-intensive process. Finding a way to produce magnesium domestically using renewable energy, then, is not only an economic and environmental issue, it’s a strategic one. “With a flick of a finger, China could shut down steelmaking in the U.S. by ending the export of magnesium,” said Alex Grant, Magrathea’s CEO and an expert in the field of decarbonizing the production of metals.

“China uses a lot of coal and a lot of labor,” Grant continued. “We don’t use any coal and [use] a much lower quantity of labor.” The method is low cost in part because the company can use wind and solar energy during off-peak hours, when it is cheapest. As a result, Grant estimates their metal will cost about half that of traditional producers working with ore.

Magrathea — named after a planet in the hit novel The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy — buys waste brines, often from desalination plants, and allows the water to evaporate, leaving behind magnesium chloride salts. Next, it passes an electrical current through the salts to separate them from the molten magnesium, which is then cast into ingots or machine components.

While humans have long coaxed minerals and chemicals from seawater — sea salt has been extracted from ocean water for millennia — researchers around the world are now broadening their scope as the demand for lithium, cobalt, and other metals used in battery technology has ramped up. Companies are scrambling to find new deposits in unlikely places, both to avoid orebody mining and to reduce pollution. The next frontier for critical minerals and chemicals appears to be salty water, or brine.

Brines come from a number of sources: much new research focuses on the potential for extracting metals from briny wastes generated by industry, including coal-fired power plants that discharge waste into tailings ponds; wastewater pumped out of oil and gas wells — called produced water; wastewater from hard-rock mining; and desalination plants.

Large-scale brine mining could have negative environmental impacts — some waste will need to be disposed of, for example. But because no large-scale operations currently exist, potential impacts are unknown. Still, the process is expected to have numerous positive effects, chief among them that it will produce valuable metals without the massive land disturbance and creation of acid-mine drainage and other pollution associated with hard-rock mining.

According to the Brine Miners, a research center at Oregon State University, there are roughly 18,000 desalination plants, globally, taking in 23 trillion gallons of ocean water a year and either forcing it through semipermeable membranes — in a process called reverse osmosis — or using other methods to separate water molecules from impurities. Every day, the plants produce more than 37 billion gallons of brine — enough to fill 50,000 Olympic-size swimming pools. That solution contains large amounts of copper, zinc, magnesium, and other valuable metals.

Disposing of brine from desalination plants has always been a challenge. In coastal areas, desal plants shunt that waste back into the ocean, where it settles to the sea floor and can damage marine ecosystems. Because the brine is so highly concentrated, it is toxic to plants and animals; inland desalination plants either bury their waste or inject it into wells. These processes further raise the cost of an already expensive process, and the problem is only growing as desal plants proliferate globally.

Finding a lucrative and safe use for brine will help solve plants’ waste problems and, by using their brine to feed another process, nudge them toward a circular economy, in which residue from one industrial activity becomes source material for a new activity. According to OSU estimates, brine from desalination plants contains $2.2 trillion worth of materials, including more than 17,400 tons of lithium, which is crucial for making batteries for electric vehicles, appliances, and electrical energy storage systems. In some cases, mining brine for lithium and other metals and minerals could make the remaining waste stream less toxic.

For many decades manufacturers have extracted magnesium and lithium from naturally occurring brines. In California’s Salton Sea, which contains enough lithium to meet the nation’s needs for decades, according to a 2023 federal analysis, companies have drilled geothermal wells to generate the energy required for separating the metal from brines.

And in rural Arkansas, ExxonMobil recently announced that it is building one of the largest lithium processing facilities in the world — a state-of-the-art facility that will siphon lithium from brine deep within the Smackover geological formation. By 2030, the company says it will produce 15 percent of the world’s lithium.

Miners have largely ignored the minerals found in desalination brine because concentrating them has not been economical. But new technologies and other innovations have created more effective separation methods and enabled companies to focus on this vast resource.

“Three vectors are converging,” said Peter Fiske, director of the National Alliance for Water Innovation at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in Berkeley. “The value of some of these critical materials is going up. The cost of conventional [open pit] mining and extraction is going up. And the security of international suppliers, especially Russia and China, is going down.“

There is also an emphasis on — and grant money from the Department of Defense, the Department of Energy, and elsewhere for — projects and businesses that release extremely low, zero, or negative greenhouse gas emissions and that can be part of a circular economy. Researchers who study brine mining believe the holy grail of desalination — finding more than enough value in its waste brine to pay for the expensive process of creating fresh water — is attainable.

Improved filtering technologies can now remove far more, and far smaller, materials suspended in briny water. “We have membranes now that are selective to an individual ion,” said Fiske. “The technology [allows us] to pick through the garbage piles of wastewater and pick out the high-value items.” One of the fundamental concepts driving this research, he says, “is that there is no such thing as wastewater.”

NEOM, the controversial and hugely expensive futuristic city under construction in the Saudi Arabian desert, has assembled a highly regarded international team to build a desalination plant and a facility to both mine its waste for minerals and chemicals and minimize the amount of material it must dispose of. ENOWA, the water and energy division of NEOM, claims that its selective membranes — which include reverse and forward osmosis — will target specific minerals and extract 99.5 percent of the waste brine’s potassium chloride, an important fertilizer with high market value. The system uses half the energy and requires half the capital costs of traditional methods of potassium chloride production. ENOWA says it is developing other selective membranes to process other minerals, such as lithium and rubidium salts, from waste brine.

The Brine Miner project in Oregon has created an experimental system to desalinate saltwater and extract lithium, rare earth, and other metals. The whole process will be powered by green hydrogen, which researchers will create by splitting apart water’s hydrogen and oxygen molecules using renewable energy. “We are trying for a circular process,” said Zhenxing Feng, who leads the project at OSU. “We are not wasting any parts.”

The concept of mining desalination brine and other wastewater is being explored and implemented all over the world. At Delft University of Technology, in the Netherlands, researchers have extracted a bio-based material they call Kaumera from sludge granules formed during the treatment of municipal wastewater. Combined with other raw materials, Kaumera — which is both a binder and an adhesive, and both repels and retains water — can be used in agriculture and the textile and construction industries.

Another large-scale European project called Sea4Value, which has partners in eight countries, will use a combination of technologies to concentrate, extract, purify, and crystallize 10 target elements from brines. Publicly funded labs in the U.S., including the Department of Energy’s Ames Laboratory, at Iowa State University, and Oak Ridge National Laboratory, in Tennessee, are also researching new methods for extracting lithium and other materials important for the energy transition from natural and industrial brines.

At the Kay Bailey Hutchison Desalination Plant in El Paso, Texas, which provides more than 27 million gallons of fresh water a day from brackish aquifers, waste brine is trucked to and pumped into an injection well 22 miles away. But first, a company called Upwell Water, which has a facility near the desalination plant, wrings more potable water from the brine and uses the remaining waste to produce gypsum and hydrochloric acid for industrial customers.

There are hurdles to successful brine mining projects. Christos Charisiadis, the brine innovation manager for the NEOM portfolio, identified several potential bottlenecks: high initial investment for processing facilities; a lack of transparency in innovation by the water industry, which might obscure problems with their technologies; poor understanding of possible environmental problems due to a lack of comprehensive lifecycle assessments; complex and inconsistent regulatory frameworks; and fluctuations in commodity prices.

Still, Nathanial Cooper, an assistant professor at Cambridge University who has studied metal recovery from a variety of industrial and natural brines, considers its prospects promising as environmental regulations for a wide range of industries become ever more stringent.

“Companies that produce wastewater are going to be required to do more and more to ensure the wastewater they dispose of is clean of pollutants and hazardous material,” he said. “Many companies will be forced to find ways to recover these materials. There is strong potential to recover many valuable materials from wastewater and contribute to a circular economy.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Researchers explore mining seawater for critical metals on May 27, 2024.

With the rise of recommerce, parents can find and buy top brands’ children’s products —…

The post Earth911 Podcast: Kidsy.co Takes A Step Toward Circular Children’s Products appeared first on Earth911.

The fashion industry is responsible for 10% of annual global carbon emissions. That means it…

The post Good, Better, Best: Shopping for Natural Fibers appeared first on Earth911.

In Puerto Rico, residents are flocking to rooftop solar and backup batteries in search of more reliable, affordable — and cleaner — alternatives to the central power grid. Fire stations, hospitals, and schools continue adding solar-plus-battery systems every year. So do families with urgent medical needs and soaring utility bills. The technology has become nothing short of a lifeline for the U.S. territory, which remains plagued by prolonged power outages and extreme weather events.

But a political challenge by a powerful government entity threatens to slow that progress, according to local solar advocates and Democratic members of the U.S. Congress.

The new development, they warn, could make it particularly hard for communities and lower-income households to access the clean energy technology. Puerto Rico may also lose the momentum it needs to achieve its target of generating 100 percent of electricity from renewables by 2050.

At issue is Puerto Rico’s net-metering program, which compensates solar-equipped households for the electricity their panels supply to the grid.

In January, Puerto Rico Governor Pedro Pierluisi, a Democrat, signed a bill extending the island’s existing net-metering policy through 2031, noting later that the program is key to meeting the government’s mandate to “promote and incentivize solar systems in Puerto Rico.” But the Financial Oversight and Management Board, or FOMB, is pushing to undo the new law — known as Act 10 — by claiming that it undercuts the independence of the island’s energy regulators.

The battle is brewing at a time when the U.S. government is spending over a billion dollars to accelerate renewable energy adoption in Puerto Rico, including a $156.1 million grant through the Solar for All initiative that focuses on small-scale solar. The purpose of these investments is to slash planet-warming emissions from Puerto Rico’s aging fossil fuel power plants while also keeping the lights on and lowering energy costs for the island’s 3.2 million residents.

In a May 17 letter, nearly two dozen U.S. policymakers urged the FOMB to preserve net metering. Among the letter-signers were some of the leading clean energy advocates in Congress, including U.S. Representatives Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Raúl M. Grijalva, and Senators Martin Heinrich and Edward Markey.

“Any attempt to reduce the economic viability of rooftop solar and batteries by paring back net metering should be rejected at this critical stage of Puerto Rico’s energy system transformation,” the policymakers wrote.

Today, Luma Energy, the private consortium that operates the island’s transmission and distribution systems, gives customers credits on their utility bills for every kilowatt-hour of solar electricity they provide. Those incentives help justify the costs of installing rooftop solar and battery systems, which can run about $30,000 for an average-size system, according to the Solar and Energy Storage Association, or SESA, of Puerto Rico.

Around 117,000 homes and businesses in Puerto Rico were enrolled in net metering as of March 31, 2024, with systems totaling over 810 megawatts in capacity, according to the latest public data provided by Luma.

That’s up from more than 15,000 net-metered systems totaling over 150 MW in capacity in 2019 — the year Puerto Rico adopted its 100 percent renewables goal under Act 17.

“One of the main drivers [of solar adoption] here is the search for resiliency,” said Javier Rúa-Jovet, the chief policy officer for SESA.

“But it has to pencil out economically too. And if net metering isn’t there, it will not pencil out in a way that people can easily afford it,” he told Canary Media. He said that net metering “is the backbone policy that allows people who are not rich to install solar and batteries.”

At the same time, new programs are starting to stitch all these individual systems together in ways that can benefit all electricity users on the island.

For example, the clean energy company Sunrun recently enrolled 1,800 of its customers in a “virtual power plant,” or a remotely controlled network of solar-charged batteries. Since last fall, Luma has called upon that 15 megawatt-hour network over a dozen times to avoid system-wide blackouts during emergency power events, including three consecutive days last week.

Renewables now represent 12 percent of the island’s annual electricity generation, up from 4 percent in 2021, based on SESA’s analysis of Luma data. Small-scale solar and battery installations, made affordable by net-metering policies, are responsible for the vast majority of that growth — and undoing those incentives could cause progress to stall out, as has been the case in the mainland U.S.

Until recently, Puerto Rico’s net-metering program seemed safe from the upheaval affecting other local policies. A handful of states — most notably California, the nation’s rooftop solar leader — have taken steps to dramatically slash the value of rooftop solar, often arguing that the credits make electricity more expensive for other ratepayers.

Before Governor Pierluisi signed Act 10 into law, the Puerto Rico Energy Bureau had been scheduled to reevaluate the island’s net-metering policy — a move that solar proponents worried would lead to weaker incentives.

Despite making significant progress, the territory is still far from meeting its near-term target of getting to 40 percent renewables by 2025, and many view rooftop solar and batteries as key to closing that gap.

That’s why Puerto Rico’s policymakers opted to delay the bureau’s review and lock in the existing financial incentives for at least seven more years. Under the new law, regulators can’t undertake a comprehensive review of net metering until January 2030. Any changes wouldn’t take effect until the following year, and even then they’d apply only to new customers.

However, in April, the Financial Oversight and Management Board urged the governor and legislature to undo Act 10 and allow regulators to study net metering sooner. When that didn’t happen, the board made a similar appeal in a May 2 letter, threatening litigation to have the law nullified.

The FOMB was created by federal law in 2016 to resolve the fiscal crisis facing Puerto Rico’s government, which at one point owed $74 billion to bondholders. The board consists of seven members appointed by the U.S. president and one ex officio member designated by the governor of Puerto Rico. The entity has played a central and controversial role in reshaping the electricity system — which was fragile and heavily mismanaged even before 2017’s Hurricane Maria all but destroyed the grid.

According to the FOMB, Act 10 is “inconsistent” with a fiscal plan to restructure $9 billion in bond debt owed by the state-owned Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority, which makes the money to pay back its debt by selling electricity from large-scale power plants. Act 10 also “intrudes” on the Puerto Rico Energy Bureau’s ability to operate independently, the board wrote, since it prohibits the bureau from studying and revising net metering on its own schedule.

“Puerto Rico must not fall back to a time when politics rather than public interest … determined energy policy,” Robert F. Mujica Jr., FOMB’s executive director, wrote in the letter.

While the board said it “supports the transition to more renewable energy,” its members oppose the way that Puerto Rico’s elected officials acted to protect what is one of the island’s most effective renewable-energy policies.

In recent days, solar advocates, national environmental groups, and Democratic lawmakers in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Congress have moved swiftly to defend Puerto Rico’s net-metering extension. They claim that efforts to undo Act 10 are less about upholding the bureau’s independence and more about paving a way to revise net metering.

“For the board to basically attack net metering really goes against what my understanding was for their creation, which was to look out for the economic growth of the island,” said David Ortiz, the Puerto Rico program director for the nonprofit Solar United Neighbors.

The renewables sector in Puerto Rico contributes around $1.5 billion to the island’s economy every year and employs more than 10,000 people, according to the May 17 letter from U.S. policymakers.

Ortiz said his organization “is really counting on net metering” to support its slate of projects on the island. Most recently, Solar United Neighbors opened a community resilience center in the town of Cataño, which involved installing solar panels on the roof of the local Catholic church. The nonprofit has also helped residents in three neighborhoods to band together to negotiate discounted rates for solar-plus-battery systems on their individual homes.

Javier Rúa-Jovet of SESA noted that net metering has already undergone extensive review. That includes a two-year study overseen by the U.S. Department of Energy, known as PR100, which analyzed how the island could meet its clean energy targets. The study suggests that net metering isn’t likely to start driving up electricity rates for utility customers until after 2030, the year the Energy Bureau is slated to revisit the current rules. PR100’s main finding, which is that Puerto Rico can get to 100 percent renewables, assumes the current net-metering compensation program continues until 2050.

The fiscal oversight board has requested that legislation to repeal or amend Act 10 be enacted no later than June 30, the last day of Puerto Rico’s current legislative session. After that point, the FOMB says it will take “such actions it considers necessary” — potentially setting the stage this summer for yet another net-metering skirmish in the U.S.

Should policymakers heed the FOMB’s demands, advocates fear it could become harder to develop clean energy systems, particularly within marginalized communities that already bear the brunt of routine power outages and pollution from fossil-fuel-burning power plants on the island.

“In a moment where the federal government is investing so much money to help low-income communities access solar, the FOMB on the other side trying to affect that just doesn’t make sense,” Ortiz said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Puerto Rico’s rooftop solar boom is at risk, advocates warn on May 26, 2024.

On a pair of aging piers jutting into New York Harbor, contractors in hard hats and neon yellow safety vests have begun work on one of the region’s most anticipated industrial projects. Within a few years, this expanse of broken blacktop should be replaced by a smooth surface and covered with neat stacks of giant wind turbine blades and towers ready for assembly.

The site will be home to one of the nation’s first ports dedicated to supporting the growing offshore wind industry. It is the culmination of years of work by an unlikely alliance including community advocates, unions, oil companies, and politicians, which hope the operations can help New York meet its climate goals while creating thousands of high-quality jobs and helping improve conditions in Sunset Park, a polluted neighborhood that is 40 percent Hispanic.

With construction finally underway, it seems that some of those hopes are coming true. Last month, Equinor, the Norwegian oil company that is building the port, signed an agreement with New York labor unions covering wages and conditions for what should be more than 1,000 construction jobs.

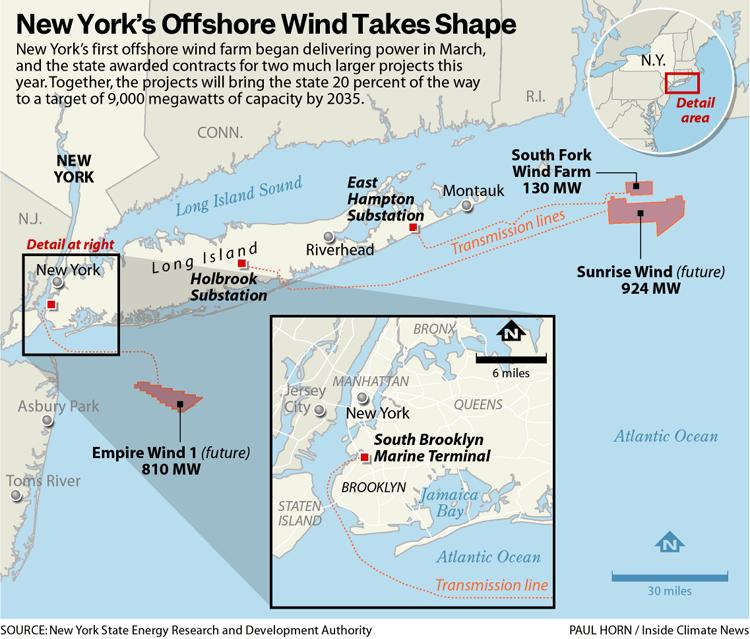

The Biden administration has been promoting offshore wind development as a key piece of its climate agenda, with a goal of reaching 30,000 megawatts of capacity by 2030, enough to power more than 10 million homes, according to the White House. New York has positioned itself as a leader, setting its own goal of 9,000 megawatts installed by 2035.

Officials at the state and federal levels have seized on the industry as a chance to create a new industrial supply chain and thousands of blue-collar, high-paying jobs. In 2021, New York lawmakers required all large renewable energy projects to pay workers prevailing wages and to meet other labor standards. The Biden administration has included similar requirements in some leases for offshore wind in federal waters to encourage developers to hire union labor.

While the last year has brought a series of setbacks to the offshore wind industry, including the cancellation of several projects off New Jersey and New York that faced rising interest rates and supply chain problems, many of the pieces for offshore wind are falling into place. New York’s first utility-scale project began delivering power in March, while two much larger efforts, including one that Equinor will build out of the new port, are moving toward construction. Together, they will bring the state about 20 percent of the way to its 2035 target.

Community leaders in Sunset Park have cheered these wins, but they say it remains unclear how many of these jobs will actually go to residents of the neighborhood, a working-class community where the port is being built. It was the promise of green industrial jobs that brought community activists together with Equinor and political leaders to rally behind a proposal to redevelop the South Brooklyn Marine Terminal.

Now, as work proceeds, the effort helps highlight how difficult and complicated it can be to pair the transition to green energy and job creation with environmental justice concerns, even when all the players pledge support to that goal.

“It’s a thing that often falls off the table,” said Alexa Avilés, who represents Sunset Park on the New York City Council, about the priorities of communities. She worries that efforts to hire locally might bring workers from other parts of New York City or state, “and then we, the local community, never see any direct benefit. We see all the workers coming in and our folks are unemployed.”

On a gray day in March, about 100 union members and government and corporate officials gathered in a glass-walled meeting room overlooking Queens, in a training center run by the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers. They were there to celebrate the signing of a project labor agreement between Equinor and local unions, versions of which will be required for similar projects up and down the East Coast.

Senator Charles Schumer, the New York Democrat and majority leader, said it was the culmination of years of work, including the hard-fought passage of an infrastructure law and then the Inflation Reduction Act, which ushered in renewable energy tax credits and financing, much of which is pegged to labor standards.

“New York can be the center of offshore wind in the whole country,” Schumer said. “But I said, ‘I’m not doing this unless labor is included and labor is protected.’ We don’t want to see low-wage jobs with no pensions and no health benefits build this stuff. We want good pay. We want good benefits. We want good health care.”

The transition away from fossil fuels has brought uncertainty to workers in the energy sector. While the number of jobs in the renewable energy industry has been growing, wind and solar generation have lower unionization rates than coal or natural gas, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. Many people have expressed fears that building electric vehicles will require fewer workers than conventional cars, though there may be little data to support that concern.

For labor leaders and many Democrats, offshore wind has been the counter to these fears. A report by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory estimated that a domestic offshore wind industry in line with the Biden administration’s goals could create as many as 49,000 jobs, and New York and other states have been enacting legislation aimed at encouraging the industry to create as many jobs as possible with high labor standards.

More than 400 miles up the coast, Kimberly Tobias successfully lobbied the state legislature in Maine, where she is completing an apprenticeship with the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, to require some of the same standards that New York had adopted in 2021. Tobias grew up about 15 miles from the town of Searsport, which Governor Janet Mills recently selected as the site for Maine’s first offshore wind port. Tobias said the development will provide steady work that has been elusive in the renewable energy sector.

“This is my 21st solar field in three years,” Tobias said, speaking via Zoom from a solar development where she was taking a break from installing panels. “The promise of being able to go to the same place for a project that’s projected to be five years, that’s a huge deal.”

Tobias said she hopes the offshore wind industry can help replace the jobs that Maine has lost from the decline of other industries like paper mills.

In the opposite direction, workers have already leveled the ground for a large wind port in Salem County, New Jersey, that will have room not only for staging assembly of turbines but also for manufacturing their parts.

At the signing in Queens, Schumer said, “We always thought there ought to be three legs to the stool: environment, labor, and helping poor communities that didn’t have much of a chance. And South Brooklyn Marine Terminal really met all three of the legs of the stool.”

But a more nuanced picture emerged the following week at a community board meeting in Sunset Park. There, several dozen people packed into a less glamorous room on the ground floor of a public library to hear a presentation by Equinor and its contractors about the project. Placards lining the walls advertised the benefits the project will provide the neighborhood and the state, and speakers pledged to create more than 1,000 jobs and to keep open communications with the community.

They would minimize truck traffic, they said, by coordinating deliveries and bringing in supplies by rail or barge when possible. A major elevated highway bisects Sunset Park, and two polluting “peaker” power plants line the waterfront, firing up on hot summer days when power demand soars.

They spoke about a learning center the company would build and about $5 million in grants that Equinor had given to city organizations, including funding workforce training and programming at a rooftop vegetable farm in Sunset Park.

But when it came time for questions, several community leaders echoed different versions of the same query: How many jobs will go to local residents? A confounding answer emerged.

A spokesperson for Skanska, the construction firm that was hired to build the port, said they were encouraging neighborhood residents to apply but that they need to hire through the unions. He said some small portion of jobs could be nonunion, particularly those that would come as part of a commitment to hire businesses owned by minorities and women.

The union requirements, then, might actually get in the way of hiring residents of Sunset Park.

A couple of days before the community meeting, Elizabeth Yeampierre voiced these same concerns in an interview in her Sunset Park office, where she is executive director of UPROSE, an environmental justice advocacy group that supported bringing the wind port to the neighborhood.

“There’s entire categories of people that we’re concerned about,” Yeampierre said. “We’re concerned about people who don’t speak English, people who are undocumented, people who are coming out of the prison system, mothers, single mothers with children — how are we going to make sure that those people are brought in?”

Yeampierre remains supportive and excited about the wind port and what it can bring to the community. For years, UPROSE has fought to bring green industry to Sunset Park to help clean up the community and provide working class jobs that pay better than retail and other sectors.

UPROSE received one of the community grants from Equinor to fund a “just transition training center” that will help connect people in the neighborhood with training programs in different green industries. But Yeampierre said the city’s building trade unions also need to make an effort to expand their ranks.

“The truth is that if you want to hire people locally, and you want to make sure that historically marginalized communities get first dibs,” Yeampierre said, “then you need to create avenues for them to be able to go into these industries, and into this work. I don’t see that happening.”

Vincent Alvarez, president of the New York City Central Labor Council, a coalition of 300 unions, said his members were working with city agencies and officials to encourage local hiring in offshore wind. Many of those hires, he said, could be for administrative positions, security, and warehouse jobs at the Brooklyn port, positions that will be less specialized than in construction.

An Equinor spokesperson said the project labor agreement signed with the unions includes a “local hire requirement that gives priority to union members who live in Sunset Park,” but did not say how many people that might apply to. Representatives of Equinor and Skanska have said that in addition to direct jobs, additional money will flow to the neighborhood in the form of indirect jobs, feeding the new workers, for example, or providing other supplies.

Avilés, the city councilmember, said she and other community leaders continue to support the unions.

“We will always fight for a unionized workforce, because we know how important union work is for strong working class communities. But we also know we have people that are going to be outside of that, who also need dignified work.”

Now, Avilés said, she and other community leaders will continue to press Equinor, the unions and city agencies to make sure as many jobs go to Sunset Park as possible.

“It’s annoying that the work is here upon us, and we’re still kind of asking the same questions” about what benefits will flow to the community, “but I don’t think that closes the opportunity.”

Work on the port is expected to last three years. And if the offshore wind industry expands as state leaders hope, there will be years of construction of new projects beyond that.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline As New York’s offshore wind work begins, an environmental justice community awaits the benefits on May 25, 2024.

Mexico could see record temperatures in the next two weeks, as extreme heat driven partially by El Niño blankets the country.

A lack of sufficient rainfall has left 70 percent of Mexico suffering from drought conditions, with a third experiencing severe drought, the national water commission said, as Reuters reported.

“In the next 10 to 15 days, the country will experience the highest temperatures ever recorded,” National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) researchers said in a statement, as reported by Reuters.

In the coming two weeks, temperatures in Mexico City could soar as high as 95 degrees Fahrenheit, said Jorge Zavala, UNAM’s director of the Institute of Atmospheric Sciences and Climate Change.

The capital city was one of several cities in the country that recorded its hottest day earlier this month, and most residents do not have air conditioning.

Since the beginning of the hot season on March 17, extreme temperatures have killed at least 48 people, with most dying from heat stroke and dehydration, Reuters said in another report.

Hundreds of others have suffered from sunburn and other heat-related conditions, according to health ministry data.

At this time during last year’s hot season in Mexico, three heat-related deaths had been reported.

According to meteorologists, a high-pressure heat dome over northern Central America and part of the Gulf of Mexico stopped the formation of clouds, leaving Mexico and parts of the Southern United States exposed to unrelenting sunshine and scorching temperatures, The Associated Press reported.

Warm, moist air was transported northward from the equator by tropical southerly winds, adding to the rare string of hot days.

The unusually high temperatures have killed people and animals, including threatened species like the endangered mantled howler monkey, who have been dying from what is believed to be dehydration in southern Mexico, reported Reuters.

Dr. Liliana Cortés Ortiz, a University of Michigan primatologist who is the vice chair of International Union for Conservation of Nature’s primate specialist group, said she was concerned about the plight of other species who are not as likely to be noticed, The New York Times reported.

Cortés Ortiz pointed out that, while species can adapt to changing conditions, things are happening “so fast, that it’s going to be very difficult for many species to adapt. There is not enough time,” as reported by The New York Times.

Scientists believe the increased temperatures — along with logging, deforestation and fires — may have combined to push the imperiled monkeys into smaller forested areas with lack of sufficient food, water and shade, The New York Times said.

“The animals are sending us a warning, because they are sentinels of the ecosystem. If they are unwell, it’s because something is happening,” said Gilberto Pozo, a biologist with nonprofit conservation group Cobius, as The New York Times reported.

The post Mexico Braces for Its ‘Highest Temperatures Ever Recorded’ appeared first on EcoWatch.