This story was originally published by Inside Climate News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

At the tail end of the aughts, as it became clear that the United States would need to create much more renewable energy, fast, many believed the transition would be bolstered by the proliferation of offshore wind. But not off the coasts of states like Massachusetts and California, where it’s best positioned today. They thought the industry would emerge, and then take hold, in the Great Lakes.

Things looked promising for a while. Glimmers of an offshore wind boom arose from the depths of the Great Recession, as developers offered up proposals on both the U.S. and Canadian sides of the lakes. In 2010, the Cleveland-based Lake Erie Energy Development Corporation, better known as LEEDCo, announced plans to install its first 20 megawatts by 2012 and scale up to 1,000 megawatts by 2020. Two years later, the Obama administration and five states—though not Ohio—formed the Great Lakes Offshore Wind Consortium to help streamline the permitting process.

“That was really a peak of burgeoning interest in climate,” said Greg Nemet, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who studies energy policy. “There was also a spike in energy prices just before the global financial crisis … that also stimulated awareness and interest in energy. And at the same time, the prices of renewable energy were really starting to come down.”

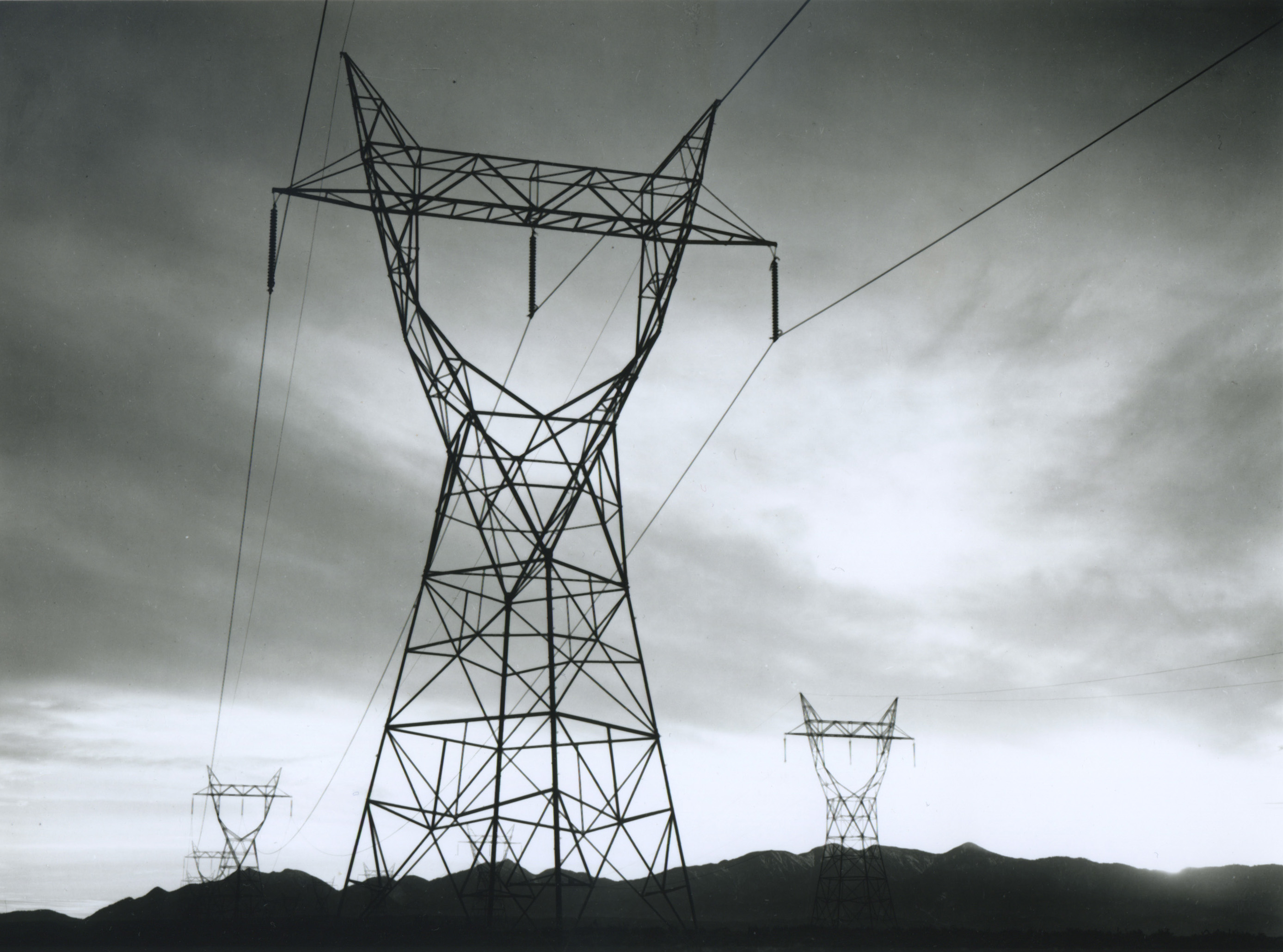

The wind that blows over the Great Lakes is stronger and more consistent than what inland wind farms receive. It holds steady even in the middle of the day, when power demand is high but generation from onshore wind farms tends to slow down. Which means that, in theory, tapping into the wind resource over the lakes would allow the electric grid to rely more on renewables without being as affected by their intermittency.

Yet more than a decade on, none of those early offshore wind projects have succeeded. There are still no commercial wind turbines in any of the five Great Lakes. And as the industry debates when, if ever, it will give the region another shot, those who tried before want newcomers to avoid making the same mistakes that they did.

Icebreaker wind

Perhaps the most famous (or most infamous) such proposal is Icebreaker Wind, the sole project of Cleveland’s LEEDCo, a public-private nonprofit launched by several lakefront counties and a local foundation in 2009. By most accounts, the six-turbine pilot project is the most successful Great Lakes offshore wind initiative of its time—even though it may never be built.

“They were really ahead of their time,” Nemet said of LEEDCo. “It’s high risk, and just because it’s high risk doesn’t mean it’s a bad idea…You can learn from success, but you can also learn from failure.”

Two key qualities set Icebreaker apart from nearly all of its counterparts: It has been permitted, and it hasn’t been canceled. It survived the labyrinth of federal reviews and state and local hearings that took out the handful of others that made it that far. And it’s being spearheaded by a developer that, despite blow after blow from local policymakers, still hasn’t given up.

These days, though, LEEDCo is struggling to overcome the resistance it’s faced from birders, anti-wind groups and fossil fuel interests.

“There was an awful lot of delay and uncertainty,” said Will Friedman, president and CEO of the Cleveland-Cuyahoga County Port Authority and the acting president of LEEDCo. (The nonprofit, which no longer has any full-time staff, is being held together by Friedman and a few other volunteers.)

Following years of permitting slowdowns, LEEDCo sparred with Ohio regulators in 2020 over conditions tacked onto a key state permit that it said would’ve killed the project, then slogged through an Ohio Supreme Court case—brought by area residents but partly funded by a coal company—that lasted another year and a half. It won both, but development has dragged on for so long now that some of LEEDCo’s initial work has become outdated.

“While we currently hold all the permits, we don’t know if we can build the project consistent with the original permits, so maybe we have to go back to the drawing board and do that over again,” Friedman said. With a resigned chuckle, he added, “Do we then open ourselves up to being sued again by opponents?”

Major barriers

The challenges LEEDCo has confronted are far from unique. Onshore renewable energy projects have long faced pushback from prospective neighbors and are, increasingly, being met with inhospitable new regulations designed to shut them down. The idea of offshore wind turbines being built within sight of beloved coastlines can have entire communities up in arms.

“I think a lot of policymakers are hesitant to get offshore wind attached to their name, because it’s such a controversial technology,” said Doug Bessette, an associate professor at Michigan State University whose work explores the acceptance of renewables. “I think people are afraid to push it forward.”

Most of the Great Lakes region has made little headway on enacting policies that would help offshore wind. Efforts to change state or Canadian provincial laws to facilitate or subsidize offshore wind projects have struggled to gain momentum. For pilot-sized wind farms like Icebreaker, designed to prove that the technology is safe and effective, but too small to take advantage of economies of scale, cost remains a nearly insurmountable barrier.

The progress made by offshore wind projects in the Northeast, where supportive policies have found more traction and turbines have actually made it into the water, could be a boon for the industry if it ever returns to the Great Lakes, according to David Bidwell, an associate professor in the University of Rhode Island’s Department of Marine Affairs.

There’s real data now on offshore wind farms’ socioeconomic impacts, along with evidence that overwhelming public opposition is not, in fact, inevitable. While the approval process would be different—Great Lakes states have more authority over the lakebed than East Coast states have over the ocean floor—and studies on things like bird migration routes wouldn’t translate very well, the region would no longer be starting from scratch.

But there are also infrastructure barriers specific to the Great Lakes, Bessette noted. U.S. supply chains for freshwater turbines, designed to resist annual icing and de-icing, don’t exist. The workforce hasn’t been trained. There are a limited number of ports deep enough to support offshore wind, and some of those don’t yet have the capacity. There’s no way to get a ship big enough to put up turbines through the St. Lawrence River and into the lakes, meaning that the first company to make it to the construction phase will probably need to build one.

Offshore wind turbines themselves have advanced considerably in the last decade and a half, thanks to ongoing research and their continued deployment in Europe and, more recently, on the U.S. East Coast. They’re sturdier. More efficient. Better at withstanding freshwater ice. All that technological progress will inevitably boost the odds of an offshore wind project one day succeeding in the Great Lakes.

The political climate may be working against them, however. In the early 2010s, and maybe even more recently than that, there was an appetite in the Great Lakes region for bold new clean energy projects, Bessette said. “I don’t know if we’re there right now.”

Still, as the developers that flocked to the Great Lakes region back then quickly learned, building wind turbines that are visible from shore has never been an easy sell, even in places that are supportive of the idea of creating more renewable energy.

Trillium power

In many ways, the Great Lakes offshore wind sort-of-boom started in Canada. Toronto-based Trillium Power led the charge. The company’s plan was ambitious: 80 turbines, situated on a shallow shelf about 10 miles off Ontario’s mainland, together capable of generating roughly 500 megawatts of electricity.

The concept went over well at first, according to John Kourtoff, Trillium’s CEO. Kourtoff felt like local officials were on his side until a swarm of other developers—over a half-dozen by some counts—got the same idea. Some of the projects, he said, were proposed very close to shore, well within the lake views of affluent communities. That’s what he believes turned the tide of public opinion.

Trillium almost made it to construction. “We were just ready to close the financing to do detailed engineering for two specialized barges that we were having made to erect the turbines,” Kourtoff said.

It was Feb. 11, 2011, a Friday, when he got the call. Facing increasing public opposition to offshore wind months, and with a general election coming up that October, Ontario had imposed a moratorium on offshore wind. Ontario officials cited a lack of scientific research on the turbines’ impacts. Offshore wind’s proponents believe, however, that the moratorium was prompted by opposition from the public and from the province’s influential nuclear power industry.

Following the cancellation, Trillium sued, ultimately securing a partial victory in response to its claim that the province had destroyed relevant evidence, but failing to convince the courts of its primary argument that officials had targeted the project unfairly when they issued the moratorium.

Twelve years later, Kourtoff hasn’t given up on his flagship offshore wind project, or on the three others he wants to build in the Great Lakes. But he hasn’t been able to move forward on any of them, either. The moratorium is still in place.

Public outcry

Toronto Hydro, the city-owned electric utility, relinquished its own vision for offshore wind after the province’s moratorium went into effect. It had planned to start with an approximately 20-turbine, 100-megawatt project at a promising site about two miles offshore, said Joyce McLean, who worked as Toronto Hydro’s director of strategic issues and oversaw its clean energy programs at the time.

“We basically put the anemometer in the lakes, collected the data, and then there was nothing for us to do, because the program disappeared,” McLean said. The province, she said, “couched [the moratorium] in terms of ‘Well, we’re going to study it.’ But they never did, and it was deemed dead.”

Residents had reacted more strongly to the proposal than the utility expected. They’d packed its public meetings to ask about what would happen to their views and their property values and whether construction would stir up old industrial toxins sitting on the lakebed. One man, McLean said, yelled in her face about the harm the project would cause him. Then the moratorium came down, and the wind project went away.

“I think that we were a cautionary tale,” McLean said.

Scandia Wind arrived in Grand Haven, Michigan, even less prepared for the backlash it would face. The prospect of somewhere between 100 to 200 turbines, some of them situated as close as a mile and a half to shore, didn’t sit well with the beachfront city. The Norwegian developer’s later decision to reduce the scale of the project by half and move it six miles offshore did little to remedy the situation. In the end, unable to win over much of the community, Scandia was all but run out of town.

“I think they came with a mindset that, ‘Well, we have crossed these thresholds in Europe, and surely the Americans, with their desire for renewable energy, would welcome similar developments in their Great Lakes,’” said Arnold Boezaart, then-director of Grand Valley State University’s Michigan Alternative and Renewable Energy Center. “Well, they miscalculated.”

Some Michigan leaders believe that the fallout from Scandia ruined the chances for any offshore wind project to move forward in the area. Boezaart disagrees. “Even without Scandia,” he said, the offshore wind industry would still be figuring out how to better navigate public concerns about safety and visibility. “But certainly, there’s no question that Scandia Wind caused a big dustup during that time.”

Looking ahead

In 2009, the New York Power Authority put out its own call for offshore wind projects aimed at a swath of eligible sites in Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. Several interested developers responded, but facing higher-than-expected costs and angrier-than-expected residents, the state-owned power organization scrapped the idea in 2011.

The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority revisited the question of Great Lakes offshore wind two years ago. Advocates hoped the results of its feasibility study, published in December 2022, would catalyze new development across the Great Lakes region. Instead, NYSERDA found that freshwater offshore wind “currently does not offer a unique, critical, or cost-effective contribution” toward the state’s climate goals, and concluded that “now is not the right time to prioritize Great Lakes Wind projects in Lake Erie or Lake Ontario.”

Walt Musial, a principal engineer and offshore wind researcher at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory who worked on the New York state feasibility study, isn’t sure turbines that are anchored to the ground will ever succeed, at least at scale, in the Great Lakes. He anticipates, though, that floating turbines will be a game-changer, tapping into some of the lakes’ best winds and potentially opening the door to the sort of growth that LEEDCo envisioned in the early 2010s.

“In Lake Michigan, for example, you can go 15, 20 miles out, get out of the viewshed of most people,” Musial said. “You can avoid the ice, you can avoid the birds and you can avoid the toxic sediments that people are concerned [about]. … So maybe we made a mistake not looking at that sooner, but I think that’s where the biggest opportunities will be in the Great Lakes.”

Floating wind turbines are still being tested. Floating freshwater wind turbines are even more experimental. But Musial is one of many offshore wind researchers who suspect that when the technology does mature, it’ll unleash a plentiful new source of relatively dependable renewable electricity—assuming, as many do, that the grid will still need it by then.

Yet none of offshore wind’s lingering limitations have dissuaded more than 50 Illinois state lawmakers from pushing for a 150-megawatt (or larger) pilot project to be built somewhere along the state’s coast. Ideally, they want it near the Southeast side of Chicago, where the low-carbon electricity the wind farm would generate and the local economic boost it would provide are both very much needed.

The Illinois Rust Belt to Green Belt Program Act would authorize surcharges on ratepayers’ bills once the pilot project goes into operation—guaranteeing it the sort of state-backed financial support that no Great Lakes offshore wind project has ever received (and which Icebreaker’s advocates, despite years of lobbying, couldn’t convince the Ohio General Assembly to provide). A Lake Michigan pilot, if built, would also supply the sort of unparalleled efficacy and impact data that the offshore wind industry has long hoped would come from Icebreaker.

The bill fell short in 2022 and again in 2023. Its backers plan to keep trying.

“Let’s get going,” said state Rep. Marcus Evans Jr., one of the bill’s sponsors. “What are we waiting for? I don’t want to be 185 years old when these things come to fruition. So we need a policy to make it happen. We need action. Things don’t just happen. You have to do something.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline What happened to the Great Lakes offshore wind boom? on Nov 28, 2023.