Every year, world leaders gather under the auspices of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change to assess countries’ progress toward reducing carbon emissions and limiting global temperature rise. The most famous of these so-called Conferences of Parties, or COPs, resulted in the landmark 2015 Paris Agreement, which marked the first time the world’s countries united behind a goal to limit global temperature increase. That treaty consists of 29 articles with numerous targets, including reducing greenhouse gas emissions, increasing financial flows to the most climate-vulnerable countries, and establishing a carbon market.

This year’s COP, which commences in Dubai on Thursday, is all about determining whether that agreement succeeds or fails. For the first time since the Paris accords, the negotiators assembled at COP28 over the next two weeks will conduct a “global stocktake” to measure how much progress they’ve made toward those goals.

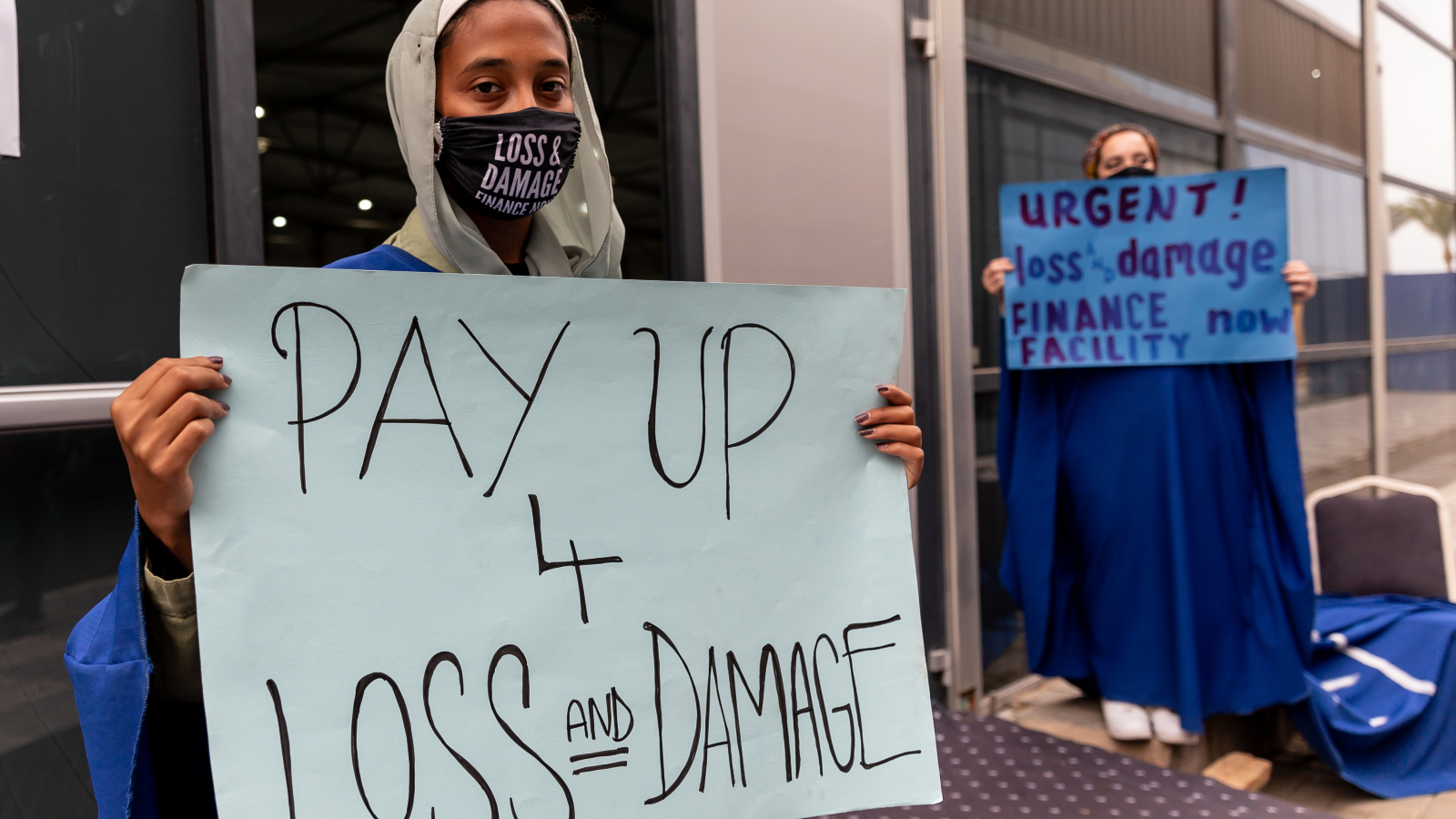

While activists up the ante with disruptive protests and industry leaders hash out deals on the sidelines, the most consequential outcomes of the conference will largely be negotiated behind closed doors. In the coming weeks, delegates will pore over language describing countries’ commitments to reduce carbon emissions, jostling over the precise wording that all 194 countries can agree to. (In past years, negotiations have been saved by shifting a single comma.)

With more than 70,000 participants expected — not just national negotiators but also academics, activists, and civil society representatives — this year’s meeting promises to be particularly contentious. The conference is being hosted by the United Arab Emirates, the world’s fifth-largest oil producer, and is being presided over by the CEO of the country’s oil company, Sultan al-Jaber. Recent media reports suggesting that he has been using the COP28 presidency to push oil and gas deals have further stoked fears that he may not be a neutral arbiter to oversee the proceedings. Against that backdrop, countries will be negotiating the precise language that signals the world’s transition away from fossil fuels.

Countries are also expected to decide whether they can commit to tripling renewable energy use and doubling energy efficiency, measures that al-Jaber is pushing and are widely seen as a barometer of a successful COP. But a number of other major issues loom over the conference. Here are the big-ticket items to watch as negotiations get underway.

– Naveena Sadasivam

Will world leaders commit to a phaseout of fossil fuels?

In 2015, the international community agreed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in order to try to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. But it wasn’t until 2021, at the COP26 in Glasgow, Scotland, that a U.N. climate deal explicitly referenced fossil fuels — the biggest contributor to climate change — for the first time. In that conference’s final decision text, which sums up the outcomes of COP discussions, diplomats agreed to pursue a “phasedown of unabated coal power” and a “phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies.” Last year at COP27, diplomats repeated the same commitment, leaving this language mostly untouched.

At both negotiations, governments fiercely debated whether to agree to a phaseout or a phasedown of coal — a subtle difference with major policy implications. Some countries, including small island nations, advocated for a full “phaseout,” which refers to a complete displacement of coal with renewables. Oil-exporting countries like Saudi Arabia and coal-reliant economies like India instead pushed for a “phasedown,” which would dramatically reduce coal use but stop short of eliminating it entirely. Efforts to limit all fossil fuels — and not just coal — have also failed in the last two years.

These debates will likely continue at COP28, according to climate policy experts. A State Department official told reporters in November that whether it’s “phasedown,” “phaseout,” or a completely different phrase altogether, the final decision of the conference will likely have some reference to the transition away from fossil fuels. In a recent joint statement, the United States and China agreed to develop renewables to “accelerate the substitution for coal, oil, and gas generation,” offering another potential wording option.

Adding to the complexity is disagreement over the use of the word “unabated.” Abated fossil fuels refers to coal, oil, and gas projects that use carbon capture technology, which the International Energy Agency recently characterized as “expensive and unproven at scale.” Wealthy nations including the U.S. and those in the European Union have called for a “phase out of unabated fossil fuels” — wording that Barbados, Finland, the Marshall Islands, and others have argued would leave the door open for “abated” fossil fuels. Those countries have instead called for a plain “phase out of fossil fuels.”

– Akielly Hu

Will developing countries be paid reparations for the loss and damage wrought by climate change?

At COP27 last year, against the backdrop of devastating floods that left one-third of Pakistan underwater, countries united behind a landmark climate reparations fund. While it was a triumph decades in the making, negotiators ultimately did little more than agree to set up a fund to pay for the “loss and damage” suffered by the world’s most vulnerable countries, who have emitted relatively little carbon but are poised to suffer outsized climate impacts. This year, countries are gearing up to figure out the nitty-gritty details of putting the fund into action.

“Loss and damage is the main event at COP, to be honest,” said Avinash Persaud, a climate envoy from Barbados.

Some of the key questions surrounding the fund began to get settled at a meeting of negotiators in Abu Dhabi earlier this month. The negotiators recommended that the World Bank host the fund and that countries that have polluted the most historically, such as the U.S., U.K., and European Union nations, be the primary donors to the fund.

The recommendations did not please all parties, particularly developing nations who cited the World Bank’s history as a U.S.-aligned, bureaucratic institution that often favors loans over direct grants. A loan system defeats the purpose of a loss and damage fund, said Kishan Kumarsingh, head of multilateral environmental agreements for Trinidad and Tobago.

“It should not be loans against which you have to pay interest because then you’re paying for your own loss and damage,” said Kumarsingh.

Over the next two weeks, COP negotiators will decide whether to adopt the recommendations from the Abu Dhabi meeting. A U.S. State Department official indicated on a call with reporters earlier this month that this was likely. Negotiators are also likely to hash out which country will host the fund and take steps toward appointing a board. Other key points include when the fund will begin paying out, as well as how vulnerable countries will be prioritized for funding. Developed nations led by the United States are also looking to rope in high-emitting developing nations, like China, to contribute to the fund.

The success of the fund depends on how much money it’s able to raise. The global cost of loss and damage is expected to exceed $300 billion a year, and representatives for developing nations have called on wealthy nations to provide a minimum of $100 billion annually by 2030. The European Union has already pledged to make a “substantial” contribution. All eyes are on the U.S. to see if it’ll pony up.

– Siri Chilukuri

Will a global carbon market save the Paris Agreement — or sink it?

For years, private companies have been using carbon markets to make progress toward their emissions reduction goals. When it’s too difficult to reduce their own climate pollution, they can buy credits equivalent to the amount of carbon dioxide “removal” generated by activities like tree-planting — carbon that allegedly, if not for the credit, would have accumulated in the atmosphere.

Now, the United Nations is trying to create its own carbon market under the Paris Agreement, to help countries reach their individual emissions reduction targets. The stakes are high: According to one estimate, allowing countries to trade carbon credits could allow them to slash 50 percent more emissions at no additional cost. But at the same time, experts are wary of replicating the private markets’ many, many flaws — including insufficient rules and oversight to ensure that sequestered carbon doesn’t escape back into the atmosphere. Some observers have described the private sector’s carbon markets as “riddled with fraud.”

To craft a better system for U.N. member states, a group of experts has been working since 2021 on recommendations for the kinds of projects that should be allowed to generate carbon credits, and how their emissions reductions should be counted. The group finalized its recommendations on November 17, less than two weeks before COP28. Among them: a definition for removals; requirements for these removals to be monitored for “reversals,” in which they release their locked-up carbon; and what to do in case of a reversal.

Now, these proposals will be discussed by a small body of negotiators at COP28 and, if all goes according to plan, presented for approval by the larger group of countries that have ratified the Paris Agreement. There’s significant pressure for countries to at least reach a compromise; if not, the expert group will likely have to wait until COP29 to submit revised recommendations.

Even under the smoothest of circumstances, however, there are still other issues to be resolved before the U.N. carbon market becomes fully functional. Notably, countries need a registry capable of tracking carbon credits as they’re generated and traded. This may not materialize until 2024. Isa Mulder, a policy expert for the nonprofit Carbon Market Watch, said it’s “unlikely” that any credits will be issued before 2025.

Mulder also criticized the expert group’s recommendations for leaving too much up to “further guidance,” meaning it’s unclear whether they’ll adequately address some of the problems that have plagued existing carbon markets.

Pedro Martins Barata, associate vice president of carbon markets and private sector decarbonization for the nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund, said there won’t be a single moment — a “ribbon cutting,” as he put it — that brings the new carbon market to life, neither during COP28 nor afterward. Rather, COP28 negotiators will “get as far as possible,” he said — far enough, he hopes, for worthy carbon credit project developers to get the ball rolling.

– Joseph Winters

Will negotiators link fossil fuel use to growing public health risks?

COP28 features an official “health day” — a first in the conference’s history — aimed at supporting “the mainstreaming of health in the climate agenda” by bringing together officials from a number of countries, including Brazil, the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, Kenya, and Egypt, to talk about the health consequences of a warming planet. The World Health Organization and the Wellcome Trust, the international philanthropic organization, are the main organizers of the event.

The fact that health is appearing on the COP agenda at all is evidence that times have changed. According to Kristie L. Ebi, a climate researcher at the University of Washington who has attended every COP since 1997, a colleague told her that every person researching climate and health back then could fit in a phone booth.

That “was not as much of an exaggeration as it should have been,” Ebi said. But it’s different now, both on the international stage and in the research community. “It seems like everybody is getting into climate and health at the moment,” Ebi added. “We need the transformation, we need the attention.”

Like many other facets of the climate crisis, however, health still isn’t being treated with the urgency it deserves. A massive report published in mid-November said climate change is putting the health of billions of people around the world at risk. Weaning the globe off of its reliance on fossil fuels is the only real course of treatment for this diagnosis. Nevertheless, a draft of an official declaration on climate and health written by COP President al-Jaber, which is set to be signed by national ministers of health at COP28’s health day, doesn’t mention fossil fuels a single time.

Millions of health workers endorsed an open letter to al-Jaber in early November demanding negotiators commit to phasing out fossil fuels and exclude fossil fuel representatives from climate and health negotiations. They have done neither, and health researchers attending the conference this year say they are concerned that the day of health sidesteps meaningful action on the subject.

“The sad thing is that time is running out,” said Ramon Lorenzo Luis Guinto, director of the planetary and global health program at St. Luke’s Medical Center College of Medicine in the Philippines. He fears that negotiations in the oil-rich United Arab Emirates will serve up lukewarm takeaways that don’t include enforceable limits or actionable targets on fossil fuel use and production. “I think we in the health sector must not be naive that we are being used to make a potentially disastrous COP look good,” Guinto said.

– Zoya Teirstein

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Here are the 4 issues to watch at COP28 on Nov 29, 2023.