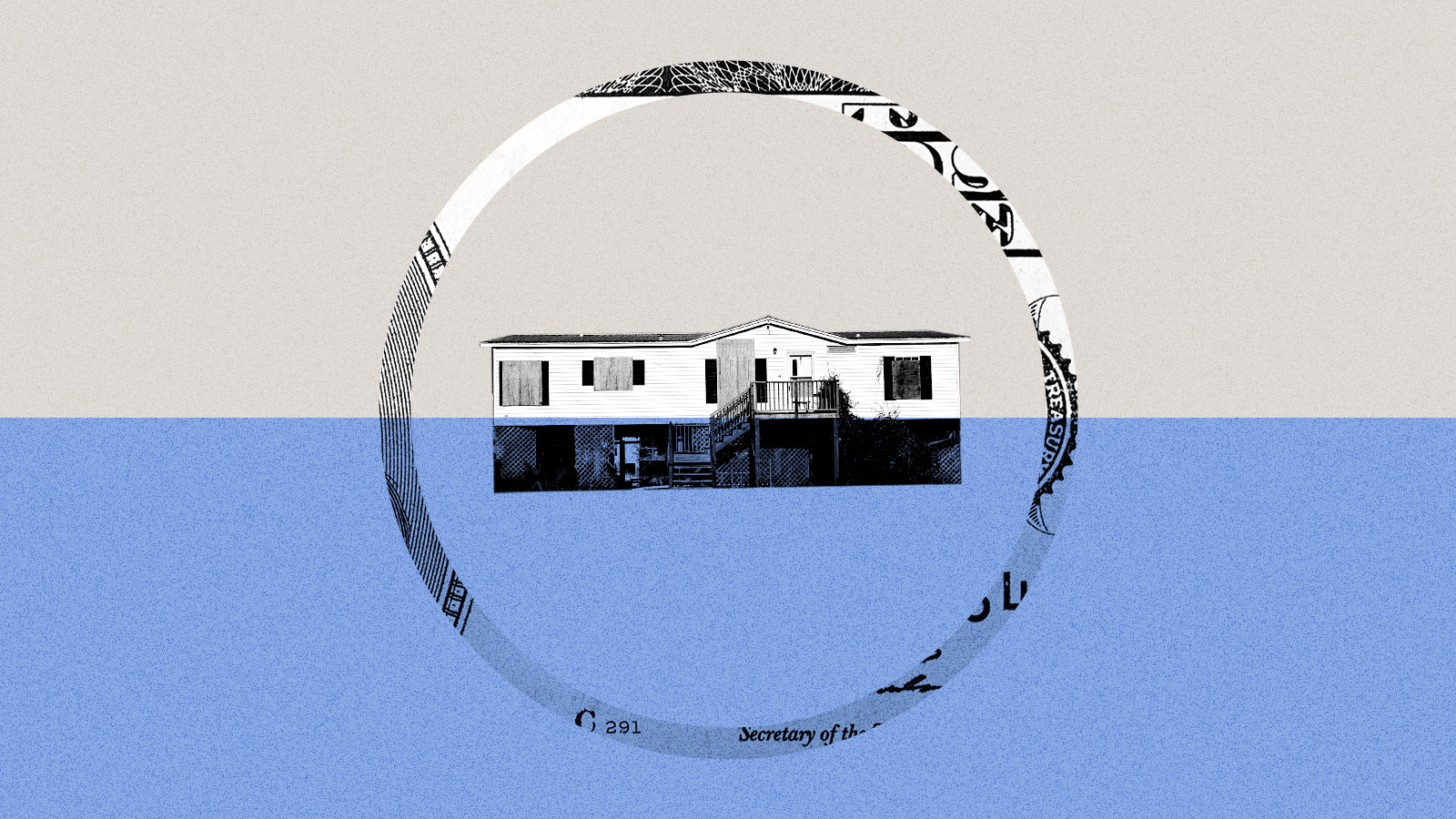

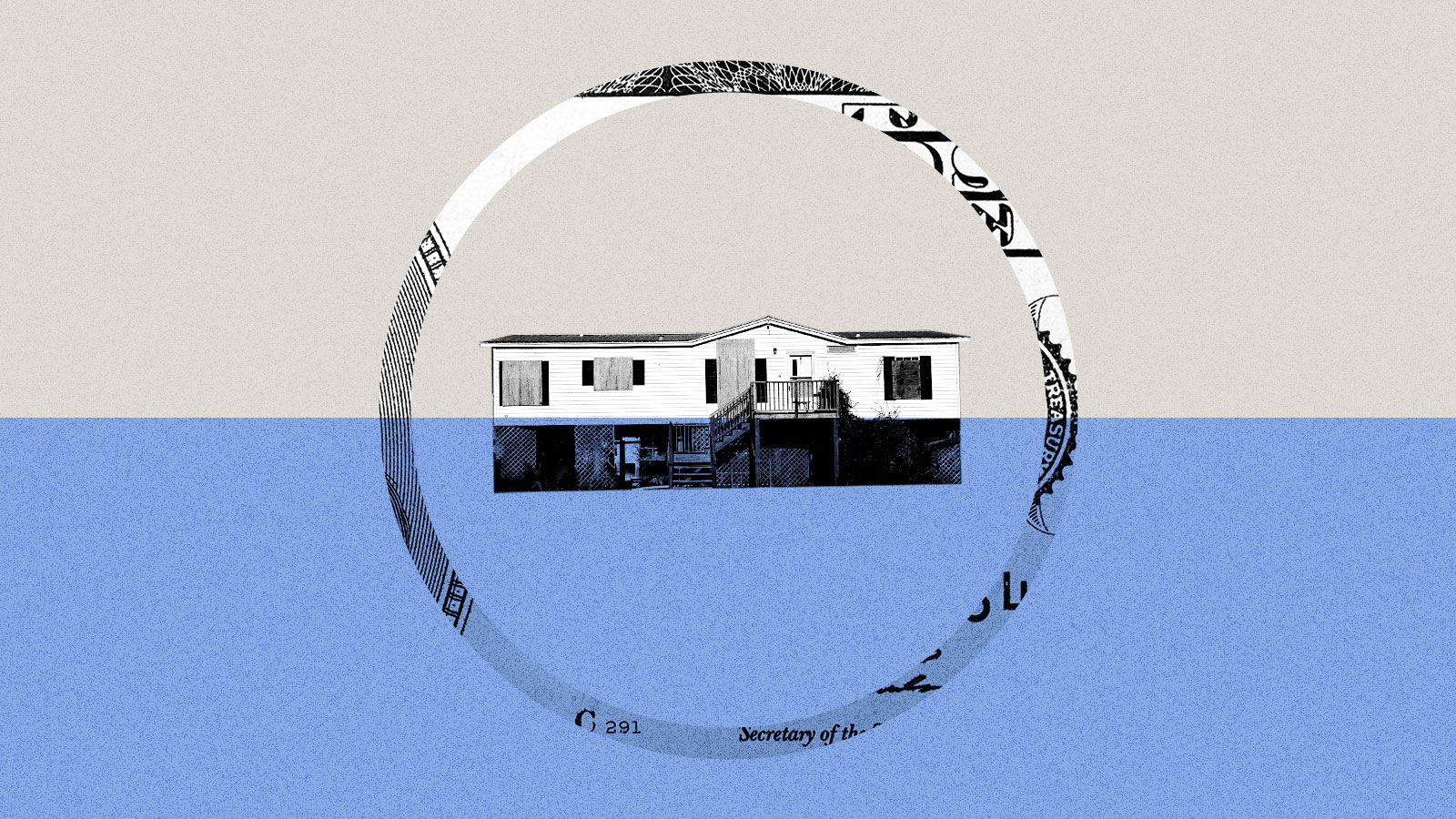

Congress created the National Flood Insurance Program in 1968 as a way for the federal government to bear a risk that private companies wouldn’t. Since then, Uncle Sam has backed the vast majority of flood insurance policies in the United States.

Yet it is impossible to buy or renew such plans directly with the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, which administers the program. Instead, the government relies upon a network of private companies to sell and service its policies — and hands them nearly one-third of the premiums the program brings in. Lately, that’s come to almost $1 billion a year.

“It is certainly something that should be examined,” said Stephen Ellis, president of the watchdog organization Taxpayers for Common Sense. “It would be one thing if it were a very high performing program. Certainly that’s not been the case.”

The government’s flood insurance program is plagued by low-participation rates and is deep in debt. How its run has often drawn scrutiny, and earlier this year, a bipartisan group of lawmakers proposed legislation that would, among other things, cap the compensation paid to private brokers, who do not take on any risk. There also have been calls for FEMA to sell policies directly to consumers. Proponents of such changes say they would make it easier, and potentially cheaper, for property owners to obtain coverage, while saving taxpayers money.

“Flood insurance is a government service,” said Rob Moore, director of the Water & Climate Team at the Natural Resources Defense Council. “People should be able to buy it directly from FEMA. No question.”

FEMA and insurance companies say it isn’t quite that straightforward.

The National Flood Insurance Act of 1968 established the National Flood Insurance Program, or NFIP, to fill a gap as the private sector retreated from the market. Five years later, Congress mandated that homeowners in high-risk areas who have a federally backed mortgage buy adequate coverage. In 1979, President Jimmy Carter assigned FEMA the role of overseeing the NFIP. But insurance uptake remained relatively low.

In 1983, FEMA enlisted private insurance agents in the effort to sell more policies. The government agreed to reimburse the cost of writing policies and processing claims. The hope was that allowing homeowners to use the same agents that sold other types of insurance would boost participation.

As dozens of companies joined the so-called Write You Own, or WYO, program, flood insurance enrollment indeed grew. But the number of policies peaked in 2009, at 5.7 million, and has been declining since.

“Even with private insurance engaged, and advertising, it still sits right around 5 million policies,” Ellis said. (As of 2022, the figure is 4.7 million.) That’s a fraction of the roughly 100 million eligible properties.

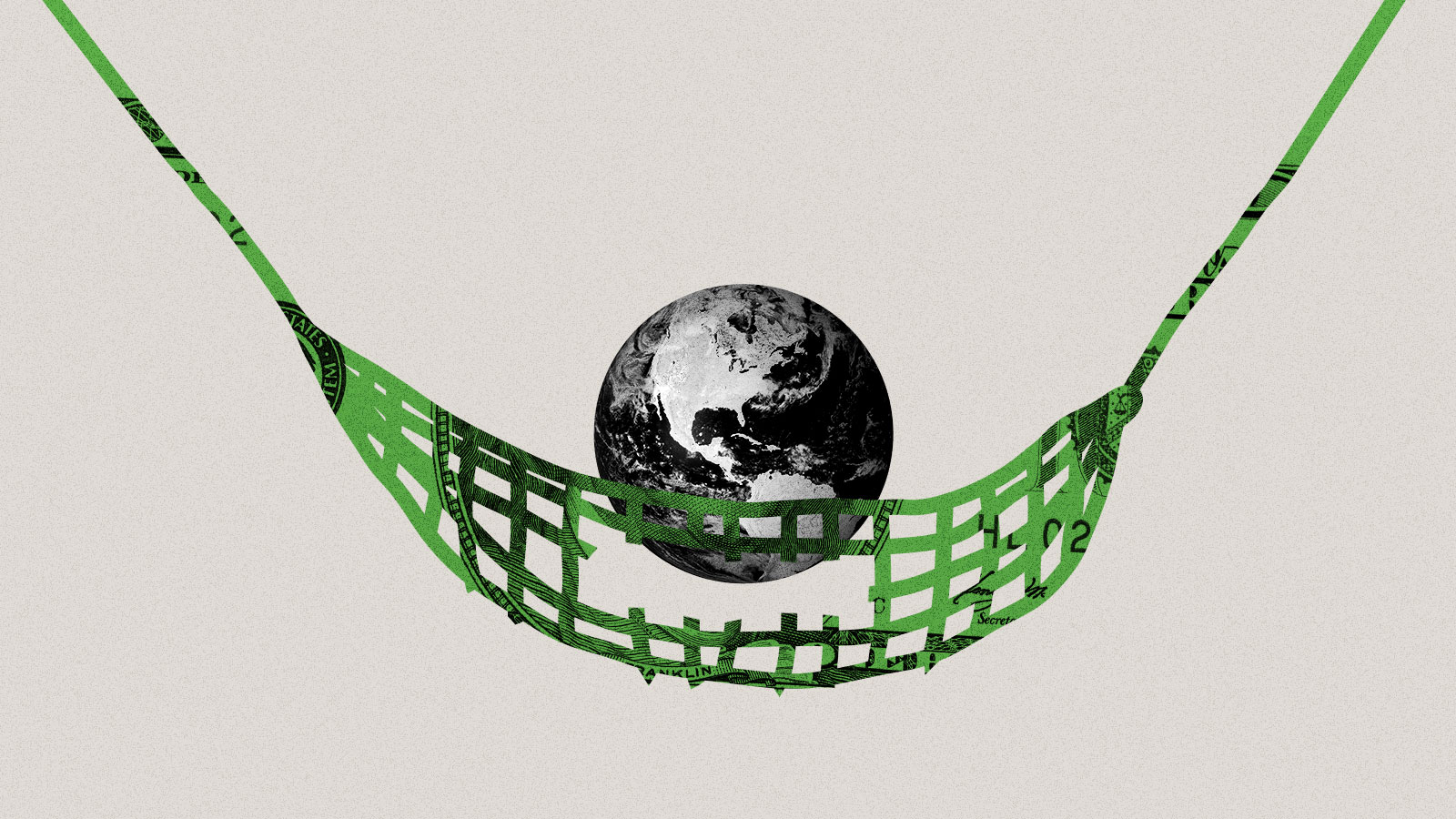

Between 2017 and 2022, the NFIP paid brokers $5.82 billion in commission and expense reimbursements. That’s nearly 29 percent of all premiums brought in by the program, which is saddled with debt and loses billions of dollars annually. Reducing that cut by even a percentage point could save millions. But the Government Accountability Office, or GAO, has on at least two occasions critiqued FEMA’s approach to compensating brokers.

“FEMA sets rates for paying WYOs for their services without knowing how much of its payments actually cover expenses and how much goes toward profit,” the nonpartisan agency noted in a 2009 report. Three years later, Congress directed FEMA to reevaluate its compensation formula. But a 2016 GAO report found that hadn’t yet happened and recommended that FEMA “improve the transparency and accountability over the compensation paid to WYO companies and set appropriate compensation rates.”

The GAO still lists that recommendation as “unresolved,” and it remains unclear how much FEMA is over- or underpaying brokers. While the GAO found that some were not being reimbursed for all of their expenses, a 2019 FEMA rulemaking proposal noted that the 30.8 percent compensation rate that the agency pays them is well above the 25.3 percent in actual expenses they reported to an industry trade group. The difference is presumably profit, which could amount to many millions of dollars.

FEMA told Grist it has completed the congressionally mandated analysis of broker compensation, but declined to share details because it’s under internal review.

What is known is that in fiscal year 2023, FEMA agreed to pay WYOs 29.7 percent of premiums. That is higher than the 20 percent cap that the Affordable Care Act generally places on the administrative, overhead, and marketing costs of health insurance sold through the government marketplace. It is also proportionally more than the 14 percent in expense payments that the Department of Agriculture has been giving companies to sell and service crop insurance for the last five years (the companies also get additional compensation as profit because, unlike WYOs, they take on crop insurance risk).

Roy Wright, who led the NFIP from 2015 to 2018, says such comparisons aren’t analogous because those programs are much larger. That allows for significantly lower overhead, he said. Still, he sees room for improvement.

“The operating costs have been the subject of a fair amount of debate,” said Wright, who is now the president of the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety. “I always think we should pay attention to how dollars are spent.”

One attempt to rein in costs came in June, when a bipartisan team of lawmakers introduced an NFIP reauthorization act that would, among other things, cap the compensation paid to private brokers at 22.46 percent. That would have saved the NFIP hundreds of millions of dollars last year alone.

“The NFIP has one million less policyholders than it did over a decade ago, but at the same time flooding, and subsequently premiums, has only increased,” said Senator Bob Menendez*, the New Jersey Democrat who is among the four lawmakers who sponsored the bill. “High administrative costs are an unnecessary burden to current policyholders and a barrier to those who want to enter. It’s time Congress rebalances the WYO compensation structure to provide premium relief and mitigation grants to grow the NFIP and reduce its risk profile.”

So far, little has happened with the bill.

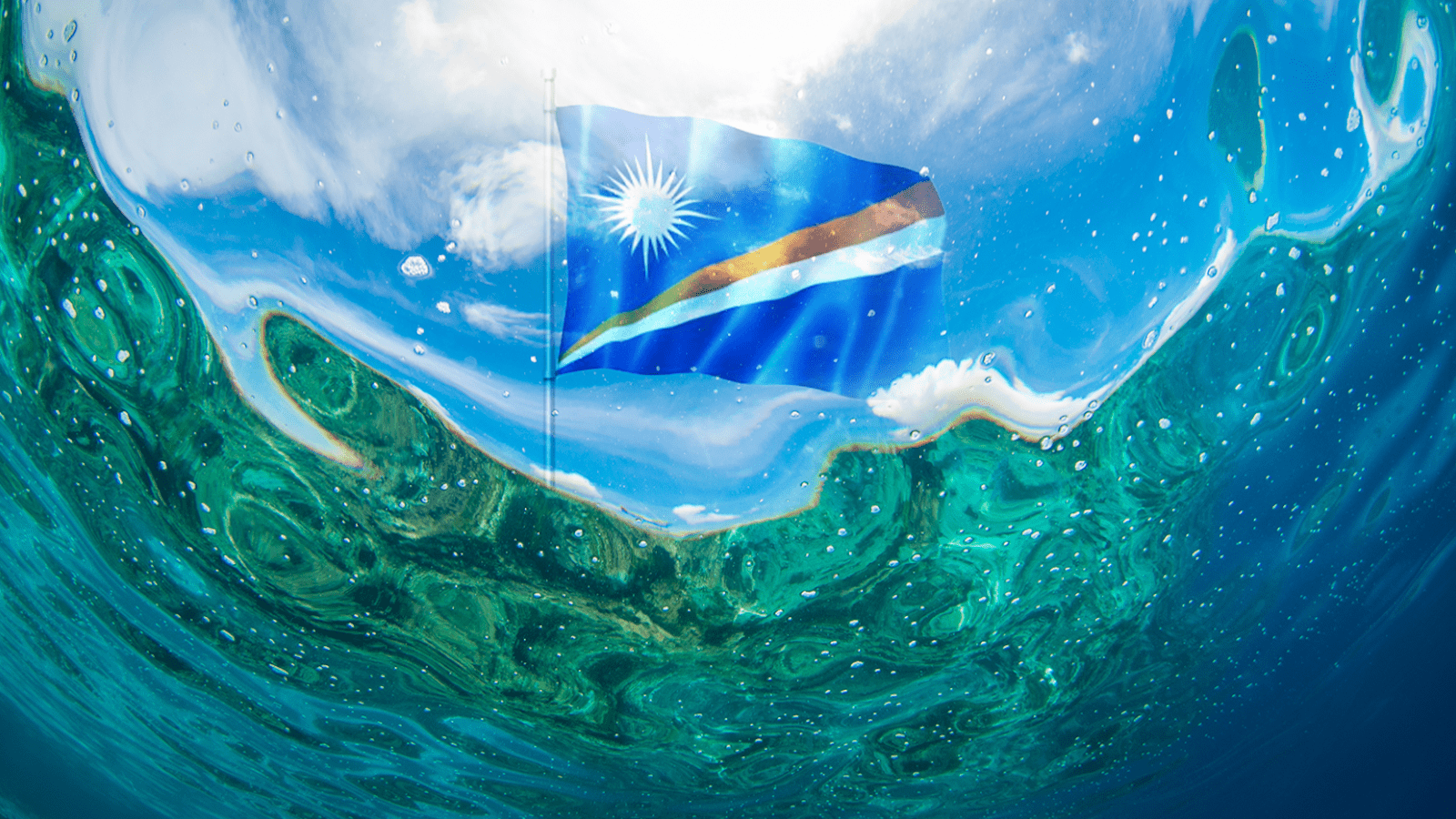

Looking beyond the matter of how much FEMA is paying brokers, some would like to see the agency interacting with consumers directly. That, they say, could cut costs while almost certainly improving access and transparency.

“Every intermediary adds one more step in the chain of telephone,” said Moore. “If more people bought directly from FEMA, there are some tangible benefits to the flood insurance programs.”

FEMA does run a program called NFIP Direct, which allows policyholders to make payments and file claims. It is somewhat similar to how the program ran before WYOs, except that today consumers must still buy a policy through a broker, who earns a 15 percent commision. According to one Democratic Senate aide, NFIP Direct’s overall expenses are about 22.46 percent, or the number proposed in the legislation.

“This is an example of where the government is more efficient than the private market,” the aide said.

Still, NFIP Direct only comprises about 1 in 10 policies. That’s at least in part because agents have minimal incentives to sell them, said Joe Rossi, a broker who chairs the Flood Insurance Producers National Committee. Agents generally find it easier — or are required — to work with private insurers they already have relationships with. Doing so also can bring more in commissions.

“The WYOs are not restricted in how much they give to their agents,” Rossi said. “There are agencies that give 20 percent or more.”

The industry argues that agent expertise is critical to helping consumers navigate a complex subject fraught with questions like, say, whether getting an elevation certificate might reduce premiums.

“The agent is the NFIP whisperer, if you will,” said Lauren Pachman, director of regulatory affairs for the National Association of Professional Insurance Agents. She added that any cuts in government payments to insurance companies would almost certainly impact agents’ commissions, which would make it more difficult to attract and retain them. The number of Write Your Owns has already been dropping, she noted. “Carriers don’t make a ton of money on the flood program.”

Less private sector involvement would require NFIP Direct to take on more of the burden — an outcome that worries her. “I guess it’s hard for me to imagine the NFIP operating like a well-run insurance company,” she said. “I worry that the federal government would be biting off more than it can chew.”

Nonetheless, FEMA says it wants to try to move closer to customers and is developing a “direct to consumer” online flood insurance quoting tool that it aims to have running by April 2025. In its initial request for information, which Grist obtained, the agency called a digital means of selling and servicing policies “imperative” and said, “Flood insurance remains behind the times, leading to potential customer frustration and the inability to protect one’s home or business.”

The hope is that fixing those issues will lead more people to sign up.

“If we’re serious about closing the insurance gap, we have to get more in tune about meeting our customers where they are,” said David Maurstad, senior executive of the National Flood Insurance Program. “What this would do is lead people through the process, at the end of which, if they decide they want to buy a policy, then we connect them with an agent who works on securing their policy.”

Maurstad did not say whether the new system would save the program money, but noted that bypassing private brokers would at the least be a logistical challenge, because insurance is regulated at the state level. The alternative would require FEMA to figure out how to have in-house agents registered in every state.

“My sense is that that would not be as effective as the co-system that already exists,” he said. “It was decided a number of years ago, and it still makes sense today, to leverage the private sector and their capabilities to administer the program on behalf of the federal government.”

Wright agrees that most people would probably benefit from professional guidance when buying flood insurance, but supports FEMA making more information easily and readily available to consumers. FEMA already has the technology needed to, say, allow someone to enter an address and get answers to most of their questions, he said: “They should find a way to turn it on.”

Whether NFIP can save money by moving more of the flood insurance process in-house is an open question, said Wright. But to the extent that there are savings, he said they should be passed on to the policy holders.

“If the cost of the insurance has gone down,” he said, “the consumers should benefit.”

*This story has been updated to include a comment from Senator Bob Menendez.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline The billion-dollar industry between you and FEMA’s flood insurance on Dec 12, 2023.