The spotlight

Hey there, Looking Forward fam. Happy Earth Day (and Earth Week, and Earth Month) — a time of year when sustainability is elevated in the global consciousness, and my inbox is full of vaguely greenwashy PR pitches.

Each April, I (and every other climate journalist) revisit the same debate: whether to “cover Earth Day” in some way, or ignore it on account of the fact that we’re immersed in these issues every day. But it struck me that Earth Day 2024 has a particularly timely theme: Planet vs. Plastics. The official Earth Day organization has been assigning yearly themes since at least 1980, and Planet vs. Plastics is hitting in the year when U.N. members are supposed to be finalizing a global treaty to address plastic pollution.

“We’ve had research for 30 years now saying that plastics are dangerous to our health,” said Aidon Charron, director of End Plastic Initiatives at EarthDay.org. But he and others at the organization chose plastics as this year’s focus because they saw a gap in public knowledge, both about the harm that plastics can cause and about the policy solutions that are currently being debated on an international stage. Discussions about plastic tend to focus on individuals doing their part by reducing, reusing, and recycling, Charron said — but “we’re not going to simply recycle our way or technology our way out of this problem.”

Charron and other advocates have been pushing for ambitious targets in the global plastics treaty, and EarthDay.org is circulating a petition, which currently has over 22,000 signatures, for some of its key objectives, which include banning the export and incineration of plastic waste and a “polluter pays” principle. “What we don’t want to see is something similar to the Paris Climate Agreement,” said Charron. “While that was a great agreement, the issue is it’s voluntary, and so countries can opt in and opt out. And there’s also no punishment if somebody doesn’t meet the standards they set for themselves.”

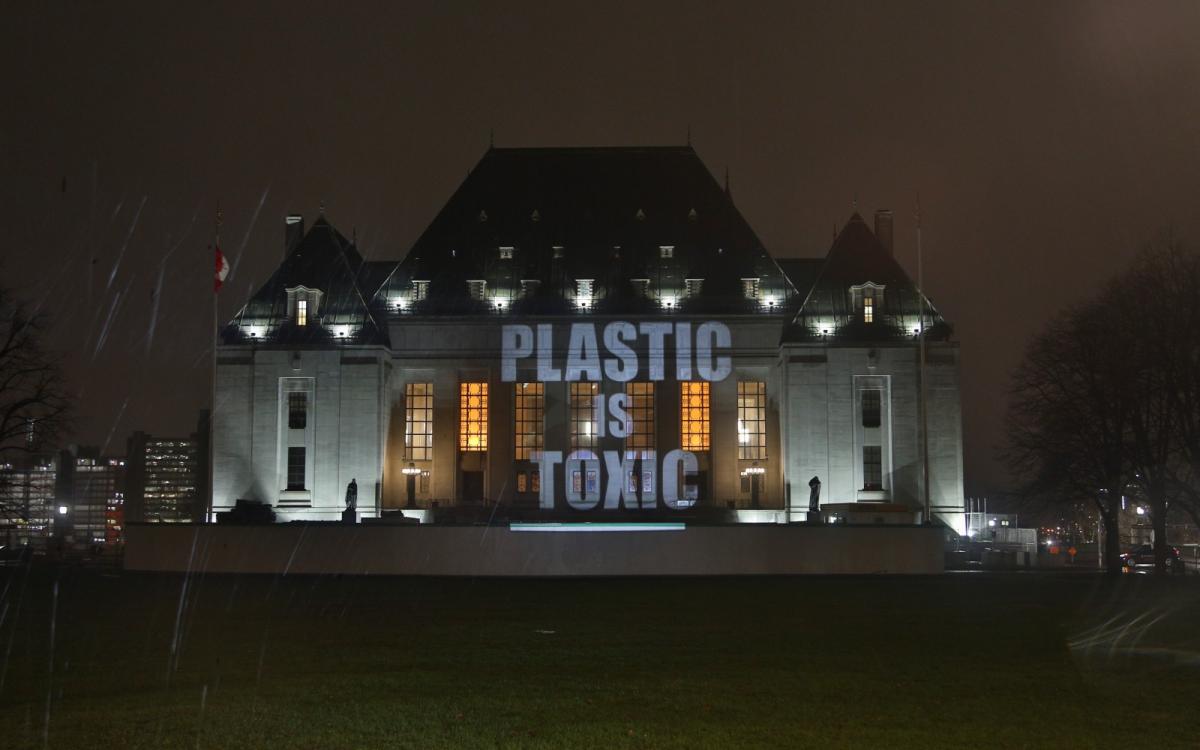

On Sunday, EarthDay.org and other campaigners organized a march in Ottawa, demanding a strong and ambitious global plastics treaty. EARTHDAY.ORG

But the negotiations on the treaty have been fraught with competing interests — and even as the deadline nears, much remains to be sorted out. This week, delegates and advocates are gathering in Ottawa, Canada, for the fourth intergovernmental negotiating committee, or INC-4 — the second-to-last session on the books before the U.N.’s self-imposed deadline to finalize the agreement at the end of this year. As the parties have failed to make significant progress at the previous three meetings, the stakes at INC-4 are high.

So, today, I’m turning the newsletter over to the capable hands of my colleague Joseph Winters, who covers the plastics industry and has been following the negotiations of the global plastics treaty for the past two years. Read on a primer on the history of the treaty, the solutions being proposed in it, and where things stand as negotiators head into another round of discussions this week.

— Claire Elise Thompson

To understand the global plastics treaty, it’s helpful to go back to the 2022 U.N. Environment Assembly meeting, where delegates agreed to write it. By then, plastics had long been considered an environmental scourge. The world was — and still is — producing more than 400 million metric tons of the material every year, almost entirely from fossil fuel feedstocks. Just five years prior, researchers had shown that 91 percent of the world’s plastics were not recycled due to high costs and technological barriers.

Agreeing to write some kind of treaty was seen as a big success, but the icing on the cake was the promise to address not only plastic litter, but “the full life cycle” of plastics. This opened the door to discussions around limiting plastic production, which most experts consider to be a nonnegotiable part of an effective mitigation strategy for plastic pollution. They liken it to an overflowing bathtub: better to “turn off the tap” — i.e., stop making plastic — rather than try to mop up the floor while the water’s still running.

Experts see the treaty as a critical opportunity to stop the fossil fuel industry’s pivot to plastic production, as the world begins to phase out oil and gas from transportation and electricity generation. None of the details are even close to being finalized — but observers have called the treaty the “most significant” international environmental deal since 2015, when countries agreed to limit global warming under the Paris Agreement. And advocates hope that this agreement will ultimately have even more teeth.

Under a very optimistic scenario, it could include global, legally binding plastic production caps for all U.N. member states, plus some details on how rich countries should help poorer ones achieve their plastic reduction targets. The treaty might ban particular types of plastic, plastic products, and chemical additives used in plastics, and set legally binding targets for recycling and recycled content used in consumer goods. It could also chart a path for a just transition for waste pickers in the developing world who make a living from collecting and selling plastic trash. But such a far-reaching agreement is by no means guaranteed; some countries and industry groups are working hard to water down the treaty’s ambition, and have thus far limited negotiators’ progress.

When delegates first met in Punta del Este, Uruguay, in November 2022, it became clear that a vocal minority of countries — mostly oil-producing states including Saudi Arabia and Russia, as well as the U.S., to some extent — wanted to bend the treaty away from plastic production limits by focusing instead on better recycling and cleanup efforts. Petrochemical companies are also pushing for a focus on recycling, despite their trade groups knowing since the 1980s that plastics recycling would be unable to keep up with booming production.

This disagreement — production versus pollution — has been central to each meeting since then, stalling progress at every turn. Although delegates have held important discussions on plastic-related chemicals and the impact of the treaty on frontline communities, by the end of INC-3 last November, negotiators still hadn’t written anything beyond a so-called “zero draft,” basically a laundry list of options and suboptions for various parts of the treaty. They also failed to agree on an agenda for “intersessional” work between INC-3 and INC-4, meaning they could not use those intervening months to continue formal discussions, although several countries arranged unofficial meetings.

In a provisional note released ahead of this week’s negotiations, INC chair Luis Vayas Valdivieso made paring down the revised zero draft a key priority for delegates at INC-4. The committee should “streamline” the document, he wrote, and set an agenda for intersessional work to be completed in the months between INC-4 and INC-5.

“INC-4 is going to be likely the most important of all the INCs,” said Ana Rocha, global plastics program director for the nonprofit Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives.

The march on Sunday began with a rally outside of Parliament Hill, where crowds heard from activists and Indigenous leaders who traveled from all over the world to join the demonstration. EARTHDAY.ORG

One of the key priorities for advocates is some kind of quantitative production limit. “If the goal is to end plastic pollution, it’ll be really hard to do without a cap on virgin plastic production,” said Douglas McCauley, an associate professor of ecosystem ecology at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Some of the most specific recommendations are based on plastic’s contribution to climate change. To limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit), the nonprofit Pacific Environment calculated last year that global plastic production should be cut by 75 percent by 2050, compared to a 2019 baseline. The Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives has proposed a 12 to 17 percent reduction every year starting in 2024.

A so-called “high-ambition coalition” of countries — including Norway, Rwanda, Canada, Peru, and a host of small island and developing states — say they support production limits as part of the plastics treaty, although they have not yet rallied around a particular target. It’s also possible that the treaty will have to rely on indirect measures to restrict plastic production, like bans on single-use plastics or a tax on plastic packaging.

Public health has emerged as another major, and surprisingly popular, priority for the treaty. Even in the two short years since world leaders first agreed to broker a treaty, lots of new evidence has emerged to highlight the human and environmental health risks associated with plastics. Last month, scientists raised the number of chemicals known to be used in plastics from 13,000 to 16,000. More than 3,000 of these substances are known to have hazardous properties, while a much larger fraction — about 10,000 — have never been assessed for toxicity. According to one recent analysis from the nonprofit Endocrine Society, plastic-related health problems cost the U.S. $250 million per year.

As of last November, more than 130 countries supported incorporating human health into the treaty’s primary objective, and many explicitly said they wanted the agreement to somehow control problematic chemicals. This is currently reflected in the zero draft, in proposals to prioritize “chemicals and polymers of concern,” putting them first in line for bans and restrictions. Some substances that would likely be included on this list are polyvinyl chloride, or PVC — the plastic used to make water pipes and some toys — as well as endocrine-disrupting chemicals like phthalates, bisphenols, and PFAS.

Bjorn Beeler, general manager and international coordinator for the nonprofit International Pollutants Elimination Network, said that chemicals are the most “matured” part of the treaty.

Other sections, however — like the financial details of how countries will pay for the provisions of the agreement — have been largely unaddressed. With so much left to negotiate and so little time, questions are swirling around whether there will have to be an additional meeting after INC-5, or perhaps an INC-4.1 during the summer.

For now, many environmental advocates say it’s important that negotiators stick to the original schedule, running INC-4 under the assumption that they can and will finish the treaty by 2025. Should they need an extension, they can consider how best to coordinate that at a later date. Rocha, with the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives, said she’d rather extend the timeline than rush through a weak agreement.

“More important than an ambitious timeline is an ambitious treaty,” she said.

— Joseph Winters

More exposure

See for yourself

Last call for the Looking Forward drabble contest! This is the final week to share your 100-word vision for a clean, green, just future, for a chance to win presents.

To submit: Send your drabble to lookingforward@grist.org with “Drabble contest” in the subject line, by the end of Friday, April 26 (two days away)!

Here’s the prompt: Choose ONE climate solution that excites you, and show us how you hope it will evolve over the next 100 years to contribute to building a clean, green, just future. We’ve covered a boatload of solutions you could draw from (100, in fact!) — so if you need some inspiration, peruse the Looking Forward archive here.

Drabbles offer little glimpses of the future we dream about, so paint us a compelling picture of how you hope the world, and our lives on it, will evolve.

Here’s what we’re looking for:

- Descriptive writing that makes us feel immersed in the scene and setting.

- A sense of time. You don’t have to put a specific timestamp on your piece, but give us some clue that we are in the future (not an alternate reality), approximately 100 years from now, and that certain things have changed.

- A sense of feeling. Is this vignette about joy? Frustration? Excitement? Nervousness? The mundane pleasure of living in a world where needs are met? Make us feel something!

- 100 words on the dot.

The winning drabbles will be published in Looking Forward in May, and the winners will receive presents! Some Grist-y swag, and a book of your choice lovingly packaged and mailed to you by Claire.

A parting shot

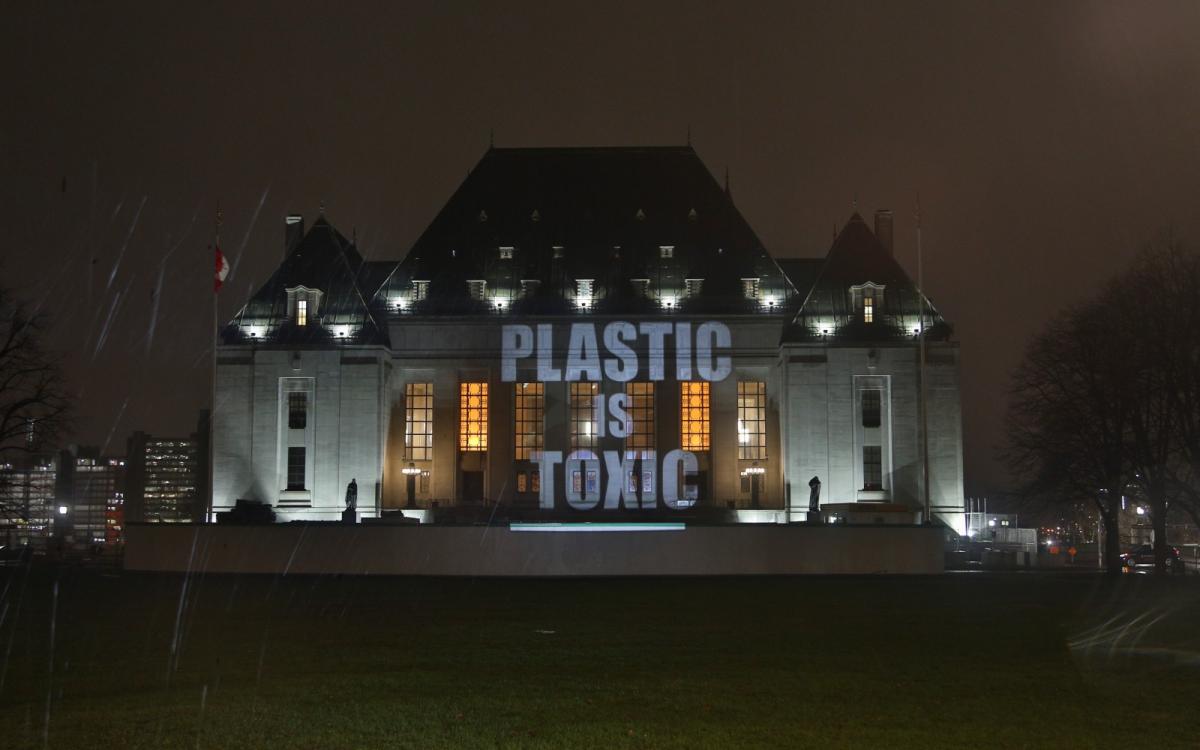

On Monday (Earth Day), in collaboration with a conservation organization called Oceana Canada, EarthDay.org projected an illuminated message onto the Canadian Supreme Court building in Ottawa, reading “plastic is toxic.” Similar messages were also projected onto Parliament Hill and the Canadian National Arts Centre, sending a clear message to leaders ahead of the treaty negotiations this week.

IMAGE CREDITS

Vision: Grist

Spotlight: EARTHDAY.ORG

Parting shot: EARTHDAY.ORG and Oceana Canada

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline On the agenda this Earth Day: A global treaty to end plastic pollution on Apr 24, 2024.