If you’ve been washing your car at home in the driveway or on the street,…

The post We Earthlings: Take Your Vehicle to the Car Wash appeared first on Earth911.

If you’ve been washing your car at home in the driveway or on the street,…

The post We Earthlings: Take Your Vehicle to the Car Wash appeared first on Earth911.

Are you ready to embark on a sustainable journey that achieves more than an ordinary…

The post How to Assess Your Business’ Environmental and Social Impacts appeared first on Earth911.

This story is the first in a four-part Grist series examining how climate change is destabilizing the global insurance market. It is published in partnership with the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

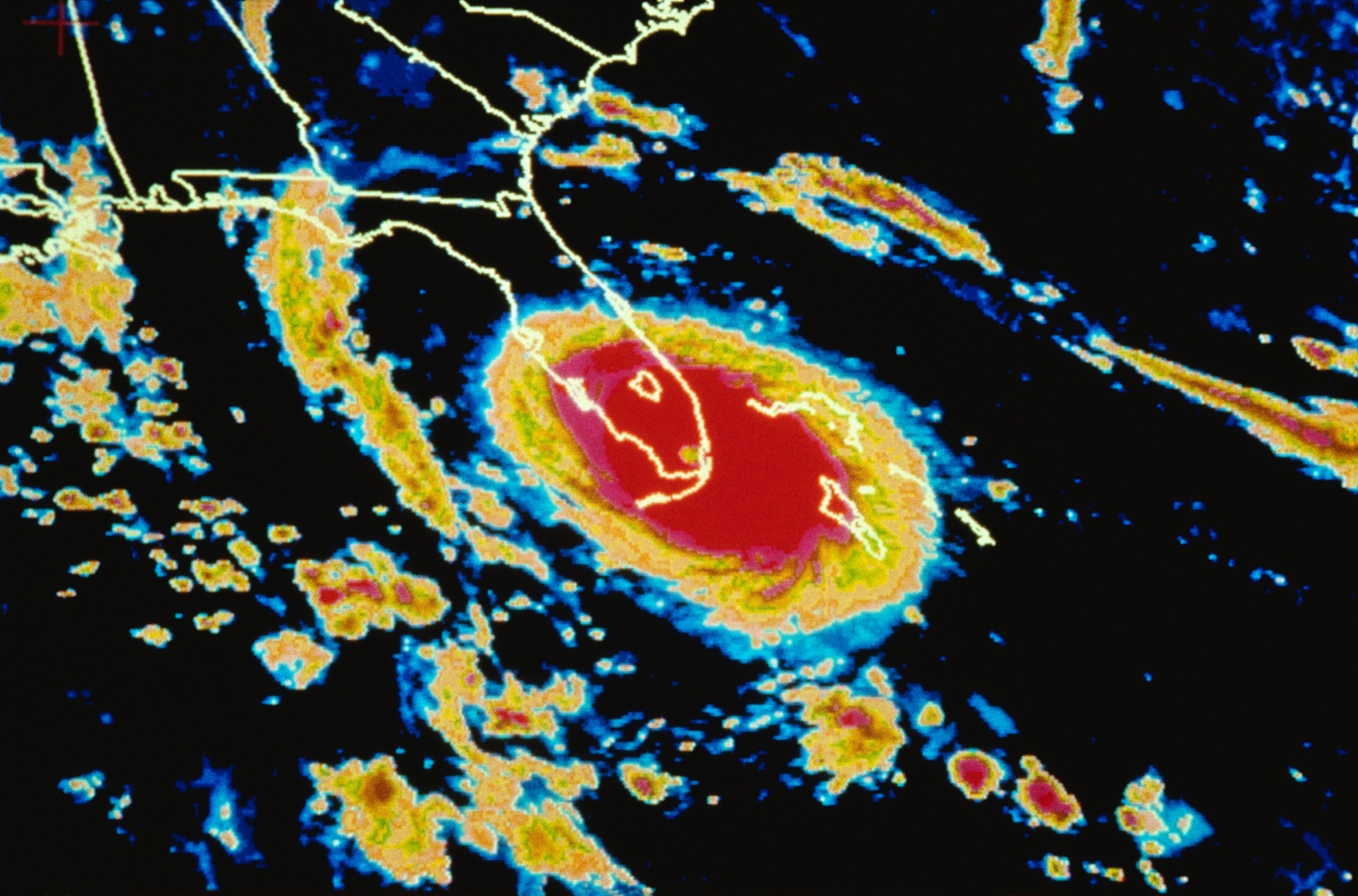

“We’ve got ourselves a little monster out there,” anchorman Jim Cantore warned, facing the camera in the Weather Channel’s newsroom on a sultry August weekend in 1992. At first, few in Florida were paying attention. “It’s very hard to get people to believe that there’s some danger from some element of nature that they haven’t experienced before,” a reporter told Cantore, as the channel played tape of tranquil beaches and neat vacation homes.

As the storm approached Florida, it gained the moniker Andrew, rapidly intensifying into a Category 5 hurricane as it exceeded wind speeds of 165 mph. Karen Clark watched updates on TV from her home in Boston with fascinated horror — and her career on the line.

Most insurance companies at that time assessed hurricane exposure in their portfolios by simply multiplying customer premiums by a rough factor of supposed risk, rather than tracking actual property replacement costs. “They were just very crude formulas,” she said.

So in 1987, Clark had started her own company, Applied Insurance Research, or AIR, to develop software that better estimated the potential losses from catastrophic events. Unlike the rest of the industry, she used granular data and sophisticated analyses, an approach now called catastrophe modeling. Her first computer model estimated that a Category 5 hurricane hitting Dade County could cause losses almost 10 times more than previously believed. She warned her customers about the risk in Florida, but until Hurricane Andrew, no one listened. “The good ol’ boys at Lloyds [of London], you know, they thought they had it all figured out,” she said. “They didn’t need any help from this American woman carrying around a little computer.”

By that Sunday morning in 1992, it became clear that Andrew’s eye was aiming straight for Miami. Clark rushed into the AIR office, where her models suggested that the storm could cause at least $13 billion in damages — a disaster so expensive at first she debated whether she should publish the results.

As the hurricane made landfall the next day, it tore palm trees from the ground and stripped roofs from houses, carving a devastating path across southern Florida. Over 100,000 homes were damaged, and an additional 50,000 were destroyed. When a client called asking about his probable losses, Clark told him around $200 million dollars. “He said, ‘For the industry?’ and I was like, ‘No. For your company.’” AIR’s estimates turned out to be conservative: Andrew eventually cost the insurance industry $15 billion.

In the aftermath, Clark said, “everyone knew the market was going to radically change.” The catastrophe models she developed quickly became the industry standard, changing how American companies navigated risk from natural disasters.

In hindsight, it was the beginning of the dynamic now driving insurance markets. To handle massive payout events like Andrew, insurance companies sell policies across different markets — historically, a hurricane wasn’t hitting Florida in the same month a wildfire wiped out a town in California. They themselves also pay for insurance, a financial instrument called reinsurance that helps distribute risk across geographic regions. Reinsurance availability remains a major driver of what insurance you can buy — and how much it costs.

But as climate change intensifies extreme weather and claims pile up, this system has been thrown into disarray. Insured losses from natural disasters in the U.S. now routinely approach $100 billion a year, compared to $4.6 billion in 2000. As a result, the average homeowner has seen their premiums spike 21 percent since 2015. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the states most likely to have disasters — like Texas and Florida — have some of the most expensive insurance rates. That means ever more people are forgoing coverage, leaving them vulnerable and driving prices even higher as the number of people paying premiums and sharing risk shrinks.

This vicious cycle also increases reinsurers’ rates. Reinsurers globally raised prices for property insurers by 37 percent in 2023, contributing to insurance companies pulling back from risky states like California and Florida. “As events are getting bigger and more costly, that has raised the prices of reinsurance in those areas,” said Carolyn Kousky, the associate vice president for economics and policy at the Environmental Defense Fund, who studies insurance. “It’s called the hardening of the market.”

In a worse-case scenario, this all leads to a massive stranded asset problem: Premiums get so high that property values plummet, families’ investments dissipate, and banks are stuck holding what’s left.

More simply, the global process for handling life’s risks is breaking down, leaving those who can least afford it unprotected.

The idea of distributing risk has been around since the 14th century, when insurers of trading ships wanted someone to share the uncertainties of long sea voyages. Modern reinsurance was established in 19th century Europe, which some historians credit to large fires in Hamburg, Germany, and Glarus, Switzerland, where significant losses led to the founding of many of today’s leading reinsurance companies.

These companies were also some of the first to issue warnings about climate change. Back in 1973, Munich Re, one of the world’s major reinsurance firms, noticed a spike in the number of flood damage claims. In a prescient report, the company noted “the rising temperature of the Earth’s atmosphere,” due to the “rise of the CO2 content of the air, causing a change in the absorption of solar energy.”

Now, the world is reaping the consequences of that change. In the last decade, the frequency of global natural catastrophes jumped by 28 percent. On a single day in July, 60 percent of the U.S. population faced an extreme weather alert. Costs have catapulted too: Since 1970, losses from disasters increased an average 5 percent a year, particularly in the United States. That’s because damage also depends on vulnerability and exposure — where people live, and how prepared they are. Tragically, the fastest-growing counties also face some of the highest risks. “It doesn’t have to be one of these huge events,” said Alice Hill, senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations who studies climate consequences. “It’s [also] successive events, back-to-back,” like the 12 atmospheric rivers that hit California this winter.

Reinsurers are particularly exposed to these hazards because many insurance companies seek primarily to cover catastrophic risks — major events like hurricanes that are intensifying as the world warms. In a letter to shareholders this summer, Christian Mumenthaler, the group CEO of global reinsurance company Swiss Re, wrote, “Climate change continues to take its toll … across multiple geographies.”

As a result, the reinsurance industry has paid dearly for much of the last decade; underwriting losses drove $115 billion in global reinsurance losses in 2022. “There’s a tension over a business model that’s retrospective, with a risk that’s emerging,” said Frank Nutter, president of the Reinsurance Association of America. The financial foundation of insurance, in other words, is cracking.

“Without global reinsurance, we wouldn’t have the capacity to provide sufficient disaster coverage for everyone,” Kousky said. “It’s essential.” But unlike insurers, who face political pressures from state regulators to keep rates affordable, reinsurance is much more of a free market. A recent report from Moody’s finds that reinsurers are reacting by raising their rates, limiting their coverage, and even deciding to reduce their exposure in places like Florida. Increasingly, the reinsurance industry is reassessing what are known as “secondary perils,” or things like flooding and wildfires — hazards that were previously less costly than major events like hurricanes, but which are becoming more common.

Because getting risk wrong is now so costly, there’s been a race in the private sector to model future odds. Jenny Dissen works at the North Carolina Institute for Climate Studies, a research institute that’s part of NOAA’s Cooperative Institute for Satellite Earth System Studies. She says she frequently fields calls from insurers eager to know the latest climate indicators. Yet critics worry this rush to fine-tune risk predictions may potentially accelerate skyrocketing premiums. Since many are proprietary, the accuracy of these assessments can be difficult to vet. They are also having unintended consequences, like lowering municipal bond ratings, hindering governments’ ability to respond to extreme weather by raising funds.

Some believe that an individual focus is likely not the best — or most equitable — way to address climate adaptation. “Many of these adaptation steps are like a kind of public good,” that can’t be taken on an individual level, like building a seawall, said Madison Condon, Boston University law professor and corporate and environmental law professor. “They work best if everyone takes them.”

The economic implications of all this are troubling. A new report by the U.S. Treasury Department, released at the end of June, found major gaps in the supervision and regulation of insurers. The report advised much closer attention to “the risks the insurance industry may pose to the overall financial sector.”

While insurance prices have soared, a recent report from the nonprofit First Street Foundation estimates that 39 million homes are covered at prices artificially lower than their true risk. The authors suggest that state regulations capping premiums and government-backed insurer-of-last-resort programs have concealed the extent of the crisis. They predict that as disasters continue surging, what they call the “growing climate bubble in the housing market” will pop — leaving millions of homes uninsurable and destroying their value. The average homeowner who loses an insurance policy automatically sees a drop of more than 10 percent in the home’s value, the report notes. “If the value of their home plummets or if the credit agencies downgrade their communities,” Hill said, “one of my big fears is we’re going to have a lot of people trapped in places that are unsafe, economically trapped.”

Such concerns prompted the Treasury Department last year to require 213 large insurers — companies like Allstate and Farmers Insurance — to provide data about their homeowner policies. Its initial goal was to collect information about coverage, claims, and premiums by zip code to identify where climate change may disrupt markets. The plan faced fierce opposition from the industry, which says it’s a regulatory burden and that disclosing this data may harm companies’ competitive advantage. Results are not anticipated in 2023, and will not include other common types of insurance impacted by climate, like flood insurance — which is often covered in a separate policy from homeowners insurance.

This spring, one of the largest insurance brokerage companies warned Congress they weren’t moving fast enough. “Just as the U.S. economy was overexposed to mortgage risk in 2008, the economy today is over-exposed to climate risk,” Aon PLC president Eric Anderson told Senate budget committee members. Yet there appears to be little federal urgency in addressing the problem.

Experts warn that increasing prices may tip homeowners toward default as more insurers flee. At least five major companies have stopped writing coverage in some regions. State Farm announced this spring that it would stop selling homeowners’ policies in California. The company cited “rapidly growing catastrophe exposure, and a challenging reinsurance market.” Allstate also quietly stopped writing new policies in the Golden State in June. In Louisiana, where at least 20 companies have left in the last two years, the situation has gotten so bad the state passed a $45 million funding bill in 2023 in an effort to woo insurers back.

Though government has been slow to address these trends, global financial markets are already basing investment decisions on climate risks. Major ratings companies like Moody’s and McKinsey have recently purchased climate data firms. First Street Foundation, for example, provides climate risk information to many banks, major reinsurers, and government agencies — including Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which are already using it to screen for mortgages’ climate exposures. Mortgage-purchasers like these, after all, are the ones who may soon be left holding the ashes of assets.

Meanwhile homeowners, many of whose mortgages require insurance, are left with limited options. After six property insurance companies in Florida declared bankruptcy in 2022, for instance, many property owners had to turn to state-run insurers, like Florida’s Citizens Property Insurance Corp., a government-backed entity serving otherwise uninsurable populations. Although its policies tend to be less comprehensive than private insurance, in the last year, its ranks swelled about 50 percent, to around 1.7 million people. Yet this year, as Florida’s reinsurance rates skyrocketed 30 to 50 percent, even these last-resort policy rates spiked 12 percent, leaving many families to weigh whether they can afford to keep their insurance.

If the state is hit by a major hurricane, the program has grown so large the resulting claims could outstrip Citizens’ budget. The program can’t go out of business like a private company, but if it runs out of money, Florida law allows Citizens to issue one-time bills charging customers up to 45 percent of their annual premium. Someone who just lost their home in a hurricane, in other words, could be facing a surprise bill of thousands of dollars.

Not only is that bad for the families whose losses aren’t protected, it deepens existing inequities. Right now, the insurance market is unintentionally protecting wealthy property owners while socializing their risk through highly subsidized premiums. The federal government holds the liability for the majority of flood insurance, for example, managed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Repeatedly flooded properties make up just 1 percent of the program’s policies but account for more than 30 percent of the claims. “When the government’s the backup insurer, the taxpayers have to support that,” Hill said.

Two out of every three American homes are now underinsured, meaning owners may face major financial losses if they were to endure a disaster. The effects won’t be felt equally. There can be an inherent tension between climate-related financial risks and anti-redlining efforts: People of color who have long suffered discrimination are now disproportionately living in areas at greater danger of disaster. That makes it difficult to both price climate risks and not divest from underserved communities.

Despite being one of the first to understand these perils, insurers continue to contribute to them. They’ve played a major role in emissions for decades: Without insurance, fossil fuel companies have difficulty obtaining financing. Coal is an apt example of what happens when insurers withdraw from a market — since 45 insurers are phasing out of coal policies, construction of new coal-fired power declined by 84 percent between 2015 and 2018.

But insurers have been slower to move away from oil and gas, in part because it’s a larger part of many companies’ business. In June, the Senate Budget Committee sent letters to major insurance companies asking for information about how much each company earns from the fossil fuel industry. “[I]t is difficult to understand how the industry can carefully price and manage climate risk in some areas of its business,” committee members wrote, “while simultaneously having no apparent plan to phase out its underwriting of and investment in the projects and companies generating the emissions that are causing these very harms.”

Prompted in part by concerns over this kind of liability, the reinsurance industry has begun warning about the need to reduce climate risk. “The economic and insured losses over time are a clear indicator that the past is not a representation of the future,” said Raghuveer Vinukollu, head of climate insights at Munich Re US. Physical mitigation, like building flood walls and buffer zones will be needed, he says, but funding and building these engineering measures can be difficult.

With insurers themselves running out of insurance options, the stability of financial systems is far shakier than many realize. Yet the federal government hasn’t developed a national adaptation plan that comprehensively addresses these concerns. In its absence, decisions are left to municipal and state governments, some of which are facing serious blowback. When Hawai‘i recently attempted to increase setbacks for future oceanfront construction, for example, citing immediate sea-level rise, homeowners managed to stall the plan. Experts like Condon call for a centralized national climate service that can help guide these adaptations and regulatory policies, based on transparent and specific risk assessments.

“If you want to know the truth, the science is the easy part,” Karen Clark said. Getting people to change their behavior, on the other hand, is difficult. She is still working on catastrophic modeling, now at her eponymous firm, where she urges decisionmakers to get more realistic, and quickly. “People don’t understand a basic economic law — there’s no free lunch. There’s a risk,” she said. “Somebody’s paying for it. It’s just a question of who.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline As climate risks mount, the insurance safety net is collapsing on Oct 10, 2023.

This story is part of Record High, a Grist series examining extreme heat and its impact on how — and where — we live.

This summer was the hottest ever recorded, and 2023 is on track to be the hottest year in history. Next year is likely to be even warmer thanks to a strengthening El Niño, a cyclical weather pattern that contributes to above-average temperatures across much of the globe. The extreme heat has made the consequences of more than a century of reckless reliance on fossil fuels impossible to ignore.

As it gets hotter, more people will succumb to heat-related illnesses. The average number of heat-associated deaths that occur every year in the U.S. rose 95 percent between 2010 and 2022. That data doesn’t include this year’s record-breaking summer. The good news is that heat-related illness is highly treatable. The key is to get the right resources to the right places in time to save lives.

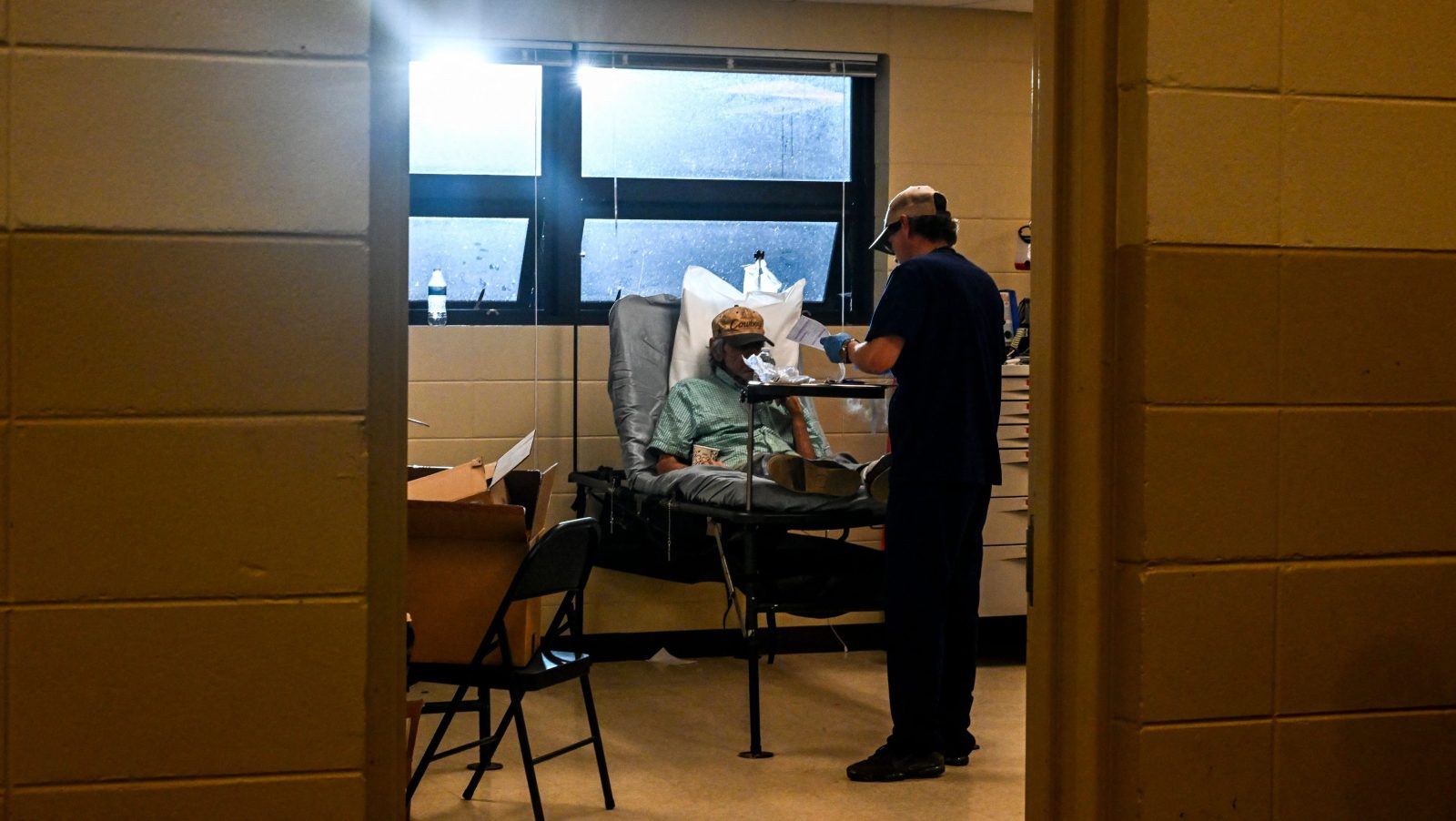

A first-of-its-kind initiative called the Climate Health Equity for Community Clinics Program aims to fight back against the rising tide of heat-associated illnesses in the U.S. by getting resources and training into the hands of doctors and the communities they treat. The program, announced last month by the global health and development nonprofit Americares and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, is the result of a year of research on the climate-related health threats that clinicians across the nation face on a daily basis. Heat, the primary cause of weather-related deaths in the U.S. in 2022, quickly floated to the top of the list of clinicians’ concerns, followed by wildfire smoke. Americares and Harvard, with $2 million in funding from Johnson & Johnson, the multinational pharmaceutical company, partnered with 10 clinics in Florida, Louisiana, and Arizona. The program aims to expand to 100 clinics by 2025.

The idea behind the program is to ensure that medical professionals at free clinics and community health centers, which work closely with disadvantaged, uninsured communities, identify which of their patients are most vulnerable to extreme heat and arm them with the tools they need to avoid ending up in the hospital with heat-related illness or heatstroke. Providers at participating clinics will be able to type patient information, symptoms, and relevant environmental factors into an online tool and receive a tailored heat mitigation plan from Americares and Harvard. Clinics in the program will also be alerted when dangerous heat waves are bearing down on their area.

“It’s all about preparedness and how we can help save lives when these heat disasters happen,” said Suzanne Roberts, chief executive officer at the Virginia B. Andes Volunteer Community Clinic in Port Charlotte, Florida. Her clinic, which has served its community since 2008, is one of the first 10 pilot clinics being funded by the new program. “We see our patients coming in with heatstroke, we see our patients coming in with nausea, and they don’t understand that it is related to the heat. We hope to learn the rules of the road so when this happens — and it will continue to happen — we will be prepared.”

Excessive heat erodes human health in a staggeringly wide array of ways. Heat affects our motor functions, appetite, quality of sleep, and our drug and alcohol intake. It puts stress on our bodies and exacerbates underlying conditions such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes. It damages our mental health and affects the medications people take to keep depression at bay. It worsens schizophrenia. It can cause third-degree burns from contact with pavement and hot surfaces. And when people are exposed to high temperatures for too long, heat causes their core temperature to rise. Many people, especially those without access to air conditioning, experience excessive sweating, goosebumps, headaches, dizziness, vomiting, shaking, fainting, and other symptoms of severe heat-related illness. The unluckiest — including more than 1,500 Americans last year — die.

Global health outfits like the World Health Organization and governments have long engaged in heat health action planning to prepare for the health impacts of elevated heat at the national level. Municipalities in the U.S. use this type of planning as well, but community health clinics are rarely looped in. The new program customizes this type of planning for individual clinics, providing funding for ice packs, saline drips, and nausea medication as well as recommendations for how the clinics can help their patients navigate heat outside the clinic walls.

The program also aims to bridge divides between clinicians and local public health officials and emergency management departments in order to make sure local resources are directed to the right places. “Clinics often don’t think of themselves as being an important entity when it comes to emergency response broadly,” said Nate Matthews-Triggs, associate director of climate and disaster resilience at Americares and the head of the project. “But now as we’re seeing more and more extreme weather related to climate change, they’re finding themselves on the front lines.”

For example, many cities set up cooling centers during heat waves to help keep residents without air conditioners cool, but those cooling centers often sit empty, even as hospitals fill up with patients suffering from heatstroke. That’s because a lot of people either don’t know about the cooling centers or don’t have a way to get to them. Many clinics, particularly in underserved areas, have contracts with non-emergency patient transportation — vans and buses paid for by the city or funded by the clinics to help patients get to their medical appointments. “Can they leverage those relationships to help their patients get to cooling centers?” Matthews-Triggs asked. That’s one of the interventions the program plans to try out over the next couple of years. Clinicians will also work with emergency managers to make sure air-conditioning units are being provided to those who need them most. Additionally, participating clinicians will teach community aid workers, like soup kitchen volunteers, to be able to identify symptoms of heat-related illness.

The Climate Health Equity for Community Clinics Program, with just 10 clinics in three states, is tiny right now. There are tens of thousands of health clinics across the U.S. with varying degrees of preparedness for the health impacts of climate change. Even when the program expands to its expected 100 clinics, its efforts will just be a drop in the bucket. Heat-related illnesses pose a threat to communities in every state in the nation — hundreds of millions of Americans. But experts not involved in the program told Grist that the initiative seems promising.

“Anything that can help better identify who is in need of what and where the resources are, and connect those two things, is going to be helpful in managing the response to any sort of crisis event,” said Samantha Penta, an associate professor in the department of emergency management and homeland security at the University of Albany. Clinicians, who are often seen as trustworthy by the community, are well-positioned to coordinate resources and bridge gaps between local officials and aid groups once the heat has descended. Americares and Harvard plan to use the information they gather between now and 2025 to bolster community-level responses to extreme heat, first in the U.S. and later in middle- and low-income countries around the globe.

“If they find this is a useful resource, then it’s probably something that we want to see spread,” Penta said. “Everything has to start somewhere.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline As heat-related deaths rise, a new program puts community clinics on the front lines on Oct 10, 2023.

Sewage collecting in crudely dug trenches. Failing septic tanks that send waste bubbling into backyards. These are some of the common sights across Alabama’s Black Belt, a strip of 24 continuous counties blessed with deep fertile soil but long plagued by inadequate wastewater infrastructure and the commensurate parasitic disease.

It’s a problem, advocates say, that the state has the resources to address.

The Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, opened a civil rights probe last week into the Alabama Department of Environmental Management and its implementation of a federal program designed to boost water infrastructure in communities across the country. The decision comes after advocates filed a complaint in March alleging that, for years, the state has hindered Black residents in rural areas from obtaining federal funds to update their wastewater systems.

It’s a region where children play on sewage-laden soil and an overwhelming stench envelops some neighborhoods for weeks on end.

“It’s really disgraceful and painful that people endure this, especially when we have the opportunity to fix it,” said Aaron Colangelo, an attorney at the Natural Resources Defence Council who has been working on the issue.

The March complaint was filed under Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin under any program that receives federal funding. At issue is the state’s distribution of money from the Clean Water State Revolving Fund, a federal program that provides financial assistance for states to carry out water infrastructure projects.

In urban areas, that usually means funding updates to municipal wastewater treatment plants or controlling sources of toxic pollution. But in Alabama’s sparsely populated Black Belt, where a disproportionate number of residents are Black and live in poverty, it entails providing financial support for people without access to a centralized sewer system to build onsite septic tanks. The Black Belt gets its name from its soil, a dark earthen clay that drains water very slowly, making it difficult to set up septic systems. Many of the ones that do exist are antiquated and in dire need of repairs — at least 50 percent in one rural Alabama county, according to a U.N. report from 2011.

In theory, federal dollars from the Clean Water State Revolving Fund should help. But in their March complaint, attorneys at the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Southern Poverty Law Center alleged that state regulators designed a system that makes it impossible for rural residents to access this crucial financial assistance.

One of the ways that the Alabama Department of Environmental Management does this, the complaint states, is by only allowing public bodies to receive funding, ruling out rural homeowners and community groups (in contrast, other southern states like North Carolina and Arkansas give high priority to onsite sanitation systems).

“The result is stark: Alabama has distributed more than one and a half billion dollars in Clean Water State Revolving Fund money since the program’s inception in 1987, but it has never awarded any money” to support individual households’ onsite sanitation needs, the complaint read.

A lack of wastewater infrastructure can have severe public health consequences. One study from 2017 found that one-third of residents in Alabama’s Lowndes County are dealing with hookworm, an intestinal parasite that can cause anemia and stunt children’s mental development.

The direness of the wastewater situation across the Black Belt has been well documented for more than a decade. In 2017, a U.N. poverty official toured the region and remarked that he’d never seen anything like it in the First World. A 2021 civil rights probe by the Department of Justice and the Department of Health and Human Services into the conditions in Lowndes County concluded in May with the state agreeing to identify homes with inadequate sanitation systems and updating them.

Colangelo, the lawyer at the Natural Resources Defence Council, called that settlement “remarkable,” but added that it will only solve the problem for one of the Black Belt’s counties. The EPA’s probe this week will hopefully address the issue statewide, he said, requiring regulators to accept individual household bids for onsite sanitation funding and to conduct outreach to communities that are not aware that the financial assistance exists.

Earlier this summer, the EPA dropped a high-profile civil rights complaint in Louisiana’s primary industrial corridor, where more than 100 industrial plants dump toxic pollution into the air of predominantly Black neighborhoods. While that decision prompted advocates to consider whether the agency would fail to follow through with other Title VI complaints, Colangelo told Grist that he does not expect a similar situation in Alabama.

“It’s on EPA to see it through, but we’re confident that they will,” he said.

The Alabama Department of Environmental Management has 30 days after the EPA’s announcement to respond to its probe in writing. After that, the federal agency could choose to bring all parties to the negotiating table to work out an agreement or conduct an investigation of its own.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Backyard sewage and parasitic disease: EPA opens a civil rights probe in Alabama on Oct 10, 2023.

Over the past 20 years, extreme weather events globally, like hurricanes, floods and heat waves, have cost an estimated $2.8 trillion, according to a new study. The study authors estimate the cost of the extreme weather damages from 2000 to 2019 to average around $143 billion, which breaks down to around $16.3 million per hour.

The researchers analyzed studies that used a methodology known as Extreme Event Attribution (EEA), which connects human-related greenhouse gas emissions and changes in extreme weather events. They compared these analyses to socio-economic costs from extreme weather events to determine how much of the socio-economic costs of extreme weather events are linked to climate change.

Using this method, the team identified a dataset of 185 extreme weather events from 2000 to 2019. During these events, they found a net of 60,951 human deaths that could be linked to climate change.

The researchers noted that human-related climate change could be linked to a net of $260.8 billion in damages from the 185 studied events, or about 53% of total damages. The majority of the climate change-related damages were connected to storms like hurricanes, while 16% of damages were linked to heat waves. Flooding and drought each made up 10% of net damages, and wildfires were linked to 2% of damages.

In total, the researchers found climate-change attributed costs of 185 extreme weather events from 2000 to 2019 to total $2.86 trillion, averaging $143 billion annually. Per year, the costs ranged from the low of $23.9 billion in 2001 to the highest annual cost of $620 billion in 2008. The team published their results in the journal Nature Communications.

While the figures are already significant, they are likely lower than the actual totals. Ilan Noy, study co-author and a professor at the Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand, told The Guardian that for some extreme weather events, data was limited.

“That indicates our headline number of $140bn is a significant understatement,” Noy explained, noting that heat wave data on human deaths was only available in Europe. “We have no idea how many people died from heatwaves in all of sub-Saharan Africa.”

Further, authors Noy and Rebecca Newman, graduate analyst at the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, wrote in the study that there are also immeasurable effects from extreme weather, such as trauma, loss of educational access, and job loss that would further increase the costs.

The study authors are encouraging policymakers to use their methodology to help determine how much money to target for a fund that could help countries rebuild after extreme weather events, a plan that was set at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP27) last year.

“This attribution-based method can also increasingly provide an alternative tool for decision-makers as they consider key adaptations to minimize the adverse impact of climate-related extreme weather events,” the authors concluded in the study. “This type of evidence can also fill, potentially, an evidentiary gap in climate change litigations that are attempting to force both governments and large emitting corporations to change their policies.”

The post Climate-Related Damage Costs $16 Million per Hour on Average Globally, New Study Estimates appeared first on EcoWatch.

This story was first published by The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that informs Texans — and engages with them — about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues.

State regulators on Monday released their draft rules for what to do with all the hazardous oilfield waste that’s left over once a well is drilled. The announcement gives the public one month to comment on the new rules — while some industry representatives started giving input more than two years ago, documents and interviews show.

Oilfield waste executives and consultants helped write the regulations beginning in 2021. Oil and gas business advocates also gave feedback to the Railroad Commission of Texas, which regulates the industry.

The effort was initiated by a commissioner who has investments in oilfield waste companies. Jim Wright, one of the agency’s three elected commissioners, ran for his seat with an eye on rewriting what’s known as Rule 8. Wright owns stock in several hazardous waste management companies in Texas, according to statements filed with the Texas Ethics Commission.

In an interview, Wright brushed off critics who suggest his involvement in the industry makes him a biased regulator. He said that he had little to do with re-writing the rules after he became commissioner, and that, if anything, his position on the Commission has hurt his businesses rather than helped it. Few companies want to risk doing business with companies associated with regulators, he said.

“For those who think this is my rule — what Jim Wright wants — that couldn’t be further from the truth,” Wright said. “Even before I came to office, [commission] staff knew we really needed to take a hard look at Rule 8.”

Wright said he believes the new rules will benefit all Texans, not just the oilfield waste industry.

Supporters of industry’s early involvement say the rules, which haven’t been significantly revised since 1984, needed to be changed to make the permitting process more efficient and to allow new waste recycling technologies to be permitted. Critics say the revised regulations would benefit the industry over the public.

“There’s an obvious conflict of interest if the industry gets to rewrite their own rules to their own financial benefit, and they end up writing rules that make people sick or contaminate groundwater and put our collective future at risk,” said Virginia Palacios, executive director of Commission Shift, a watchdog group that advocates for stricter financial policies for commissioners.

Michael Lozano, who does communications and government affairs for the Permian Basin Petroleum Association, which provided input on the draft rules to the Commission before they were released, disagreed.

“With all due respect to our friends on the environmental NGO side, they don’t know what the field application is; they don’t understand what operators are literally doing day in and day out,” he said. “We all want robust environmental standards.”

First: Ron Pilsner stands near the cistern where he stores well water on his property near Nordheim. The land has been in his family for over a century and sits next to a recently-built oil waste facility. Last: For the past few years, a citizen’s group has been checking the water and soil quality in the area with testing kits. Julius Shieh/The Texas Tribune

In an email, Railroad Commission spokesperson Patty Ramon said soliciting very early industry input is typical for the agency’s rulemaking process. Ramon said that at least one member of the public who had protested a facility’s permit in the past was also invited to provide early feedback.

The obscure rules govern the disposal of massive amounts of waste. Companies drill thousands of wells every year in Texas. They typically pump mud into the ground as they drill; rocky soil and a salty liquid known as “produced water” then comes up along with the oil and natural gas. All that waste has to go somewhere.

That’s where Rule 8 comes in.

The Railroad Commission uses Rule 8 to decide how companies should handle that material. Unlike most hazardous waste, the toxic muck from the oilfield is exempt from federal regulations. The state regulations govern how waste can be recycled or dumped — typically in pits near the well or in commercial hazardous waste pits.

The pits can leak toxic chemicals and radioactive materials and pollute surface or groundwater if not properly managed.

In recycling, the mud can be cleaned and used for more drilling, rocks and gravel can be used to build roads and some of the less-contaminated water can be removed for other uses. However, “produced water” is most often injected back into the earth under a different permit, a method that has caused an increase in earthquakes across West Texas.

The rule change would impose new environmental standards such as restricting where waste pits can be located; allow companies to suggest new forms of oilfield waste recycling; and limit who can protest permits, which environmental groups warn could limit public input. However, Ramon wrote that filing a protest is “not a cumbersome process” and that the changes would prevent competitors from filing protests.

Texans have until 5 p.m. on Nov. 3 to give feedback on the draft changes by filling out an online form or attending a meeting at 10 a.m. Oct. 26 at the Commission’s office or 9 a.m. Oct. 27 online at adminmonitor.com/tx/rrc. There will then be another formal proposal and chance for comment later.

Throughout the state, Texans for years have tried to stop oilfield waste dumps from moving into their communities — a fight that some say is already an uphill battle.

Southeast of San Antonio, outside a tiny city called Nordheim, drivers haul waste to a commercial pit facility next to 63-year-old Ron Pilsner’s family’s farm. His father and grandfather grew up there. A ranch-style home anchors the property, surrounded by Black Angus cattle, oak trees and grassland.

Pilsner says the facility ruined their sense of peace: Bright lights shine from it at night. There’s constant beeping from vehicles backing up and often the wafting stink of petroleum, insecticides and what he describes as a smell like skunks. He no longer wants to open the windows and he worries about the waste pits’ liners leaking and contaminating the area’s groundwater.

Nordheim residents tried to stop a San Antonio-based developer from building the pits in 2014. Pilsner’s parents, Marvin and Bernice, joined the protesters, who put up “DON’T DUMP ON NORDHEIM” signs with a skull and crossbones. The couple went at least once to Austin to ask the Railroad Commission not to approve the project.

The agency approved it anyway; a lawsuit by residents seeking to overturn the decision failed.

After Petro Waste Environmental began construction and operations, the nuisance grew bad enough that Pilsner’s dad stopped renovating the farmhouse, where he planned to retire. A typically frugal man, he spent $16,000 on new furniture, Pilsner said. He moved into a nursing home before he ever got to sleep on the new mattresses. He died last year.

On a scorching, triple-digit September afternoon, Pilsner toured the waste pit’s perimeter with Sister Elizabeth Riebschlaeger, an 87-year-old Catholic nun who had family who lived in Nordheim and who supported the residents in their fight. Riebschlaeger argued the commission needed to give citizens more of a say.

“Of course we’re defeated,” Riebschlaeger said, “but we’re still making noise.”

Waste Management, which acquired Petro Waste in 2019, said it was in compliance with the current Rule 8 and did not expect to need to make any changes based on the draft rules.

The company said it did stop accepting some materials in 2021 that smell and was investing in reducing truck traffic at the facility. “At WM, safety is a core value and we are committed to being a good neighbor,” the statement said.

Under the draft rules, only people like the Pilsners who own land adjacent to a proposed waste pit or recycling facility would be notified of a company’s intent to locate its facility there.

And only people who can prove they would suffer “actual injury or economic damage” from a waste pit would be allowed to protest a new facility permit — a definition that would limit environmental groups’ influence in stopping new pits from being built. Those people would have 15 days to file a protest, from the time the company filed the application or last provided public notice, and the company would then have 30 days to either withdraw its permit application or request an administrative hearing to settle the dispute.

The draft rules also introduce an option for companies to create pilot programs for their waste: Instead of dumping it in pits or recycling it, companies could propose alternative recycling methods not covered by the rules.

The change addresses the industry’s concern that the current regulations aren’t flexible enough to include new technologies. But environmental groups worry that new methods could get a fast-track to permits with little oversight.

The new rules otherwise update existing standards, adding detail and codifying what was internal guidance used by Railroad Commission staff. For example, under current rules the pits are required to have a plan to manage stormwater runoff, including during intense rainfall events, and cannot be located in a floodplain. Under the new draft rules, such pits also can’t be located on a beach, barrier island, or within 300 feet of wetlands, rivers, streams or lakes. Nor can they be located within 500 feet of any public water system well or intake location.

The old rules said liners for waste pits must “reasonably” prevent pollution but didn’t include specific standards. The draft rules say pits must be lined with a plastic strong enough to resist damage from crude oil, salts, acids and alkaline solutions. Critics of the commission said the new liner standards aren’t much stronger than the internal guidance used by the agency.

Critics also point out that the draft rules don’t spell out the penalties when pits leak or operators violate the rules of their permit. Ramon, the commission spokesperson, said that more details on fines would be available in the formal rule proposal and would likely be similar to existing regulations.

Fines can be determined on a case-by-case basis and could be reduced if a company demonstrates “good faith;” critics say that would give companies more wiggle room to contest fines.

The draft rules fulfill a goal and campaign promise for Wright, a Republican from South Texas who was elected to the Railroad Commission in 2020. Wright first tried to influence the agency’s regulations years ago, when he was part of the oilfield waste services industry.

Wright was the CEO and president of a Corpus Christi company called Environmental Evolutions, which hauls hazardous waste, and has investments in other hazardous waste companies, according to state filings. Along with some of his customers, Wright wanted to help guide the commission’s staff on how to more consistently apply the regulations affecting them, he said.

At the time, one commissioner agreed to give the group access to commission staff members, according to an interview Wright did on a podcast, but none of the staff actually wanted to work with them on the rules at that time. A 2019 bill to formalize a commission-appointed oil and gas advisory group failed to pass.

So Wright decided to run for a seat on the Railroad Commission.

Wright received campaign donations from the oilfield waste industry, according to campaign finance reports. NGL Water Solutions Permian LLC, the oilfield waste division for Tulsa-based NGL Energy Partners, is one of Wright’s top donors and has given him $226,000 since 2019; a company executive gave an additional $2,500. The company has also donated to the campaigns of the other two commissioners, Christi Craddick and Wayne Christian.

In an interview, Wright said that campaign fundraising was a “necessary evil” to be in politics, but that campaign donations don’t impact his decisions on the Railroad Commission and that he makes that clear to donors.

After he defeated the better-funded incumbent Ryan Sitton in an upset, Wright’s staff turned to the waste rules, internal documents show. An investigative watchdog group called Documented obtained copies of the documents through public records requests and shared them with the Tribune.

Wright’s former director of public affairs, Kate Zaykowski, helped facilitate the formation of a regulatory task force that included at least seven people from oil and gas and oilfield waste companies, including Pioneer Natural Resources and Waste Management, Inc.

Beginning in early 2021, the task force went page-by-page through a years-old attempt to revise the rules, using it as a framework to define more clearly how permits can and can’t be approved, said Kevin Ware, an environmental engineering consultant who chaired the task force. The task force then gave its proposal to the commission.

Commission staff then invited powerful oil and gas lobbying groups to take part in an “informal review” of the task force’s recommendations. Representatives from major companies such as ExxonMobil, Apache Corp. and Chevron were invited to attend commission meetings about the rules. Those companies and at least one lobbying group sent feedback and questions.

Mark Henkhaus, a consultant and former Railroad Commission employee who chaired a regulatory committee for the Permian Basin Petroleum Association, sent an email in August 2022 to a commission staff member raising concerns that an oil waste company may have been trying to craft the rules to its benefit.

“I want to make sure that the waste handlers are not using the Commission to further their business, if you know what I mean,” Henkhaus wrote. Henkhaus declined to comment.

Aaron Krejci, Wright’s director of public affairs, said that while Wright had reactivated the task force and requested their input, he was not involved in the group’s deliberations or suggestions to agency staff.

“The task force was helpful in getting the proverbial rulemaking ball rolling,” Krejci wrote in an email. But he added, “The rule which was just released is not a product of the task force, but rather the Commission staff who have been working internally on these updates for quite some time.”

And Wright said that if the regulations were simply to benefit the waste management industry, they wouldn’t change at all — the status quo is almost always better for business.

Instead, he characterizes the draft rules as a step forward in the Railroad Commission’s ability to better regulate an industry that’s dramatically changed over the last four decades and protect water resources from pollution. He points out that the rules include new setbacks from surface water and better standards for lining waste pits.

“I think it benefits Texas, not just industry,” Wright said. “I don’t see [how this rule] was formulated for the benefit of industry at all.”

Carla Astudillo contributed to this story.

Disclosure: Exxon Mobil Corporation and Permian Basin Petroleum Association have been financial supporters of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune’s journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline In Texas, oilfield companies helped to craft new waste rules for 2 years before the public got to see them on Oct 9, 2023.

The average American home produces 533 million microfibers annually, according to a 2019 study by…

The post Earth911 Podcast: Andrea Ferris on Making Polyester Biodegradable with CICLO appeared first on Earth911.

I am making a new documentary to share the plight of birds in the drought-stricken…

The post Discover The Public Lives of Birds appeared first on Earth911.