The evolution of plastic recycling is essential to cleaning up a plastic-addicted world and eliminating…

The post Best of Earth911 Podcast: Nexus Circular CEO Jodie Morgan on Plastic Recycling Progress appeared first on Earth911.

The evolution of plastic recycling is essential to cleaning up a plastic-addicted world and eliminating…

The post Best of Earth911 Podcast: Nexus Circular CEO Jodie Morgan on Plastic Recycling Progress appeared first on Earth911.

Remember when summertime meant living was easy? Summer used to be the season of backyard…

The post Extreme Weather Summer Scorecard – How Did You Fare? appeared first on Earth911.

Climate change looms larger in Louisiana than it does almost anywhere else in the United States. The state is facing down monster hurricanes as well as sea-level rise, and it still relies on a fossil fuel industry that pollutes the state’s air and erodes its wetlands.

But the state’s incoming governor, Republican Jeff Landry, doesn’t see it that way. Landry, who has served as Louisiana’s attorney general for almost eight years, is one of the most stalwart opponents of President Joe Biden’s climate policies, and he won election this fall after calling climate change a “hoax” and defending polluters.

He earned an outright majority of votes in the first round of the gubernatorial election last month, surprising many observers who thought the race would head to a second-round runoff. He will succeed the term-limited Democrat John Bel Edwards, whose commitment to climate action made Louisiana an outlier along the Gulf Coast. With a Republican-controlled legislature backing him, Landry could tug the state in a stark new direction, unwinding Edwards’ plans and bolstering support for industries with a long record of environmental issues.

Landry has made a national name for himself as Louisiana’s attorney general through aggressive litigation against the Biden administration, leading several lawsuits against Biden policies on everything from offshore oil lease sales to flood insurance to the cancellation of the Keystone XL pipeline. His most aggressive fight has been against the Environmental Protection Agency, which has been trying to address air pollution in the state’s oil and gas industry.

The latter years of Landry’s term as attorney general coincided with a major push by residents in the state’s main industrial corridors to curb the toxic pollution in their backyards. After years of regulatory rollbacks under former President Donald Trump, advocates finally saw an opportunity for systemic change after the 2020 election. During his first week in office, Biden signed an order that created two new executive bodies dedicated to addressing environmental justice, a term that refers to the disproportionate levels of pollution borne by low-income people and communities of color across the country. That same year, a federal judge ordered the EPA to begin responding to the civil rights complaints it receives, a responsibility that the agency had long ignored.

Encouraged by these developments, advocates filed two civil rights complaints against Louisiana regulators for their failure to reduce dangerous emissions in “Cancer Alley,” an 85-mile industrial corridor between Baton Rouge and New Orleans where more than 150 industrial facilities spew cancer-causing chemicals into the air of predominantly Black communities. A 2019 investigation found that many residents of the region inhale air that is orders of magnitude more toxic than the EPA’s safety standards. The EPA opened an investigation into these conditions in April 2022, and then brought together state officials, residents, and advocates to reach an agreement on how best to protect people living in the vicinity of the region’s hulking chemical plants.

Documents obtained by Grist revealed significant progress at the negotiating table, but last spring things began to sour, and Landry may have been the reason why. Adam Kron, an attorney at Earthjustice who worked on the case, told Grist that the breakdown in talks coincided with Landry’s sudden attendance in the negotiation meetings. Then, in June, Landry sued the federal government, arguing that the proceedings represented a vast overstep of the EPA’s authorities. The case could have implications beyond the EPA’s handling of the Cancer Alley complaints: Landry’s legal argument took aim at the agency’s ability to enforce Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which states that no person should, on the basis of race, color, or national origin, be subject to discrimination under any program that receives federal funding.

By challenging state regulators’ permitting of plants in majority-Black areas, Landry wrote, EPA officials were “moonlight[ing] as social justice warriors fixated on race.” In a twist, he accused federal officials of being discriminatory, arguing that their actions implied that chemical plants should be concentrated in other, whiter areas. Shortly after Landry filed suit, the EPA dropped both civil rights complaints in Louisiana, dealing a major blow to Cancer Alley residents who had fought for years to overhaul the state’s permitting and regulation of big polluters.

Kron said that the case clearly laid out the governor-elect’s vision for addressing civil rights concerns in communities facing disproportionate exposure to toxic emissions.

“As attorney general with no direct authority over [state regulators] he managed to work these agreements, and now he’ll be the one with direct control over those agencies,” he said. “It really doesn’t bode well.”

Landry has also challenged the Biden administration’s efforts to adapt to worsening climate disasters. Earlier this summer, he sued the Federal Emergency Management Agency over its new flood insurance pricing system, which has resulted in higher insurance premiums for many homeowners in coastal states such as Louisiana and Florida. Experts agree that flood insurance prices under the old system didn’t reflect rising flood risks, but Landry and several other Republican state attorneys general argued that the federal government had exceeded its authority when it raised insurance premiums.

In addition, Landry and the American Petroleum Institute, an industry group, sued the Biden administration in August in an attempt to force the administration to hold larger oil lease sales in the Gulf of Mexico. He also led Republican states in a lawsuit against the Biden administration over its attempts to set a new standard for the “social cost of carbon,” a key metric for setting climate policy. The conservative-led Supreme Court sided with the administration in 2022 and again last month.

An attorney and former sheriff’s deputy who hails from the state’s central coast, Landry has always been an ardent supporter of the oil industry. He majored in environmental science at the University of Louisiana-Lafayette and started what his campaign calls an “oil and gas environmental service company” after graduating, then went to law school before winning a single term in Congress during the “red wave” election of 2010.

In 2011, the year after the BP oil spill, Landry pushed the Interior Department to restart drilling permits in the Gulf of Mexico and compared department employees to the Nazi Gestapo when they refused to meet with him on short notice. The same year, when then-President Barack Obama gave a speech to Congress announcing his jobs plan, Landry held up a sign that read, “Drilling = Jobs.” As attorney general, he served on the board of his top political ally’s oil services company, raising ethics allegations.

Louisiana’s outgoing governor, Edwards, also supported the oil industry, and has even feuded with the Biden administration over its attempts to limit new oil drilling, but he has paired that support with action on climate change. Louisiana’s climate action plan, which an Edwards-appointed council approved last year, calls for the state to halve emissions from 2005 levels by the end of the decade, the same as Biden’s national target.

In response to Landry’s gubernatorial victory, the Louisiana Oil and Gas Association, an industry trade group, called Landry a “friend of industry” and speculated that he will continue to support the development of liquefied natural gas export terminals in the southernmost parts of the state. In 2017, Landry worked with a Houston-based businessman to import more than 300 Mexican laborers to help construct a massive new liquefaction facility in Cameron Parish, Louisiana. According to the Times-Picayune, the venture involved two firms owned by Landry, and a third owned by his brother.

Landry has called climate change a “hoax,” arguing that the Earth’s temperature has risen and fallen in cycles “repeated long before civilization of man.” He has also criticized renewable energy, arguing that the Biden administration’s focus on solar and wind is an attempt to force Louisiana into “energy poverty” and that “the D.C. swamp must face the fact that the manufacturing of wind turbines and solar panels requires natural gas, crude oil, and coal.” The political organization Climate Cabinet expects Landry to rescind Edwards’ climate plan upon taking office. Neither Landry’s state office nor his campaign responded to Grist’s request for comment.

Even so, there may be one area where the outgoing and incoming governors have common ground. During his two terms as governor, Edwards helped implement a $50 billion coastal restoration program that will leverage money from a BP oil spill settlement to protect the state’s coastline from further erosion. These coastal restoration efforts enjoy broad support from Louisiana voters in both parties, and even politicians who oppose climate action have touted levees and marsh-creation projects in their towns. During his time as attorney general, Landry endorsed a settlement deal with the mining and oil company Freeport-McMoRan that would see the company spend $100 million on this kind of erosion control, despite industry objections.

Kimberly Davis Reyher, the executive director of the Coalition to Restore Coastal Louisiana, a nonprofit advocacy group, says she’s hopeful that Landry will maintain investments in coastal restoration even if he unwinds other climate and environmental protections.

Coastal erosion is “not a partisan issue here, so you don’t have to argue about climate change,” she told Grist. “You just go down to the coast and observe the water going up and the land going down.” She added that the Edwards administration succeeded in building a bipartisan consensus around coastal restoration issues and said she’s “hopeful” that Landry will look for ways to supplement the BP erosion funding, perhaps by trying to get a larger share of lease revenue from oil and gas companies.

When it comes to other climate and environmental issues, though, she’s far less optimistic about a Landry governorship.

“We’ll see what happens,” she said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Louisiana’s new governor is one of the fossil fuel industry’s biggest defenders on Nov 8, 2023.

On the morning the Camp Fire destroyed Paradise, California, Charles Brooks was getting his kids ready for school. His eldest son, who was eight at the time, came into his room to say he smelled smoke. But Brooks didn’t smell it.

The sky darkened as they drove to school, and before long, ash was falling from the sky. Brooks decided to turn back, and as he pulled into the driveway, the school called to say classes were canceled.

“That phone call was really important,” he told Grist, “because if we had all dropped off our kids at school that morning, with what happened, we never would have gotten back to them.”

Ash began to fall so hard it sounded like rain. A burning stick landed at Brooks’ feet. “At that point I was like, ‘Hey, I think we’re out of here,’” he said.

He told the boys to pack two days of clothes and a favorite toy. He filled a bag for himself and his wife, who had already left for work in nearby Chico, and grabbed the dog. It took hours to get out of Paradise. Calls to his wife kept dropping. Fires broke out in the yards of homes as they passed. When he learned later that some evacuees drove through tunnels of fire as they fled, he felt fortunate his children hadn’t endured that.

“It was just an awful, awful experience that I would never want another person to have to go through,” Brooks said. “But many people have since. In Lahaina, California, Colorado, Oregon, lots of people have gone through a very similar experience.”

The Camp Fire, sparked by a faulty transmission line on November 8, 2018, killed 85 people and burned 14,000 homes. It destroyed 95 percent of Paradise and the neighboring town of Concow, and remains the deadliest fire in California history.

Brooks and his family lost their home that day. Almost immediately, they resolved to rebuild, and Brooks soon founded the Rebuild Paradise Foundation. It has helped hundreds of families by providing grants for building costs, like engineering fees, not covered by insurance and government assistance, and free resources, like residential floor plans pre-approved by the city building department. Last year, the foundation awarded more than $1 million to families.

Grist called Brooks, who is board chair of the foundation, to see how, five years later, his family and his town are doing. He was on his way to repair the iconic “May You Find Paradise” sign that greets drivers as they enter town. It had burned in the fire and been restored, but was damaged in last winter’s storms. “People couldn’t wait for it to be back up,” he said. “It looks a little different than it did before, but it’s going to survive.”

The same is true for Paradise. The town, once home to around 26,000 people, dwindled to only 1,000 or so after the fire. In the years since, more than one-third of the pre-fire population has returned, and some 3,000 housing units have been built. Brooks reflected on what the anniversary means to his family, what Paradise looks like now, and how in the age of wildfires, impacted communities can find ways to thrive again. His comments have been edited for length and clarity.

We moved to Paradise in 2004, before we were married. My wife and I were living and working in Chico, and the only place where we could afford to buy a house was Paradise. That was the story of a lot of people who lived here. We got a tiny fixer-upper. Within the first year, we fell in love with the community. Our neighbors were wonderful people, the type of people who would take your trash can down if you were gone on vacation. We gave neighbors eggs from our chickens. They gave us honey.

When we wanted to start a family, we moved to the house that we ended up losing in the fire. It was a fixer-upper too, a small four-bedroom house on half an acre.

It was completely destroyed. We had a friend who worked for one of the utility companies who was getting back in the next day to survey damage for his company. He asked me if we’d like to know if we lost our house. That poor guy talked to at least two dozen people to let them know that they lost their home. That’s like being the grim reaper.

It just sucked. You work most of your young adult life to finally get a piece of the dream of owning a home. And then something that you put all your blood, sweat, and tears into, where your kids took their first steps … our kids had only known that home. Those types of things come up at random times and weigh on you pretty hard.

We learned that we lost our house late morning on Friday, the day after the fire had started. That afternoon I told my wife, “Hey, I think we should rebuild.” She said OK.

The next week, we dragged ourselves to an architect’s office, exhausted, not knowing anything that we wanted. I think it took us two months for us finally to get up the courage to go back and start talking about what we wanted.

During that time, we were going through the emotions of whether to really rebuild. It took almost a month before we could get back up and see our property. With everything we were hearing and seeing through the media and pictures, it seemed like the town was completely destroyed. Everybody was saying there was no chance for Paradise.

But then you started seeing videos of how the Holiday Market survived. The Ace Hardware survived. You started seeing little glimmers of hope. There was this point in time when we said, “You know what? We absolutely love it there. The people are amazing. We can do this.”

My wife and I started talking about how we needed to do more. We started making posts and sharing pictures on social media of the little glimmers of hope.

A friend saw what we were doing and introduced me to this incredible woman, Jennifer Gray Thompson, who started the Rebuild North Bay Foundation to help people in Santa Rosa recover after the Tubbs Fire. She told me, “I can share with you what we’ve done down here, but your disaster is completely different. You have to do what makes sense for your community.”

We knew that the government was going to develop programs for the non-insured and underinsured, programs for low-income and extremely low-income people. But working folks who were kind of lower-middle class, working paycheck to paycheck, were facing housing replacement costs that had skyrocketed because of disaster economics.

At the same time, all these costs started showing up that FEMA and insurance were not going to address. We wanted to build a program around these gaps, and to develop programs that helped “the missing middle,” the group of people who are above typical assistance but not able to afford market-rate housing.

The foundation’s volunteers were going through this in parallel. So we knew that was what other people were going through. So many people have reached out to the foundation over the years to say, “I can’t believe you thought about this. It was such a lift to know that somebody else recognized how hard it is to do this.”

There’s a heightened level of awareness that you have after going through something like this.

We’ve learned a lot. The collective consciousness of the community is very fire adapted, fire aware. When you drive around town, you can see that in the way that builds are done. You’re seeing innovation. People are really paying attention to defensible space.

Our community is installing an early warning system. In case your cell phone goes down, which we saw on that day, there’s also an audible alert that lets you know. All of our utilities are going underground. The schools have more robust plans in place.

Our parks department is working with fire scientists to create buffer zones. They’re acquiring property, getting rid of thick vegetation and developing parks that are maintained and that are large enough that people can use them as safety zones.

We have people who are really focused on learning from Indigenous practices of how to work with the land. They’re learning about the cultural practices of Native Americans. We’re doing burning in a way that actually benefits the environment and reduces fire severity. Last week there were eight prescribed burns, some of them up to 8,000 acres, in our area. Five years ago, in the greater Northern California area, that never happened.

Now that we’re back, it’s absolutely amazing. It’s really cool to see houses everywhere. There’s about 600 under construction.

Then you’ve got the vibrancy of the community. As soon as they could, the chamber of commerce brought back our weekly Party in the Park and farmers market. The community comes out and sits on this big grassy hill, listens to a band playing. Kids are dancing.

Paradise was known as a retirement community, but now you notice a lot more families. There are a lot of people who are moving here because it’s still more affordable than other places in California.

The landscape looks a lot different. There used to be pine trees everywhere. We lost hundreds of thousands of trees that burned or were removed. But now almost anybody in Paradise has a sunset or a sunrise view, which is really neat.

There’s still a ton of challenges to rebuilding, and those are always going to be there. You just can’t build a home for the prices you used to. People are having to build back smaller, and get creative.

For the community, there’s been a lot of working through it. Now the big thing for us is how far we’ve come.

The recovery is different for everybody. My family and I are going to do a commemorative 5K run on Saturday. We talk about the fire openly. We don’t hide it from our kids. When they want to talk about it, we talk about it. We could go two months without talking about it, and then other times it’ll be a couple days in a row. Summertime can be a little bit triggering for the kids, especially if there’s smoke and if there’s planes flying around.

There are tributes to the people we lost, and more are being planned and built. But along with never forgetting, I think the best way we can honor the people that called Paradise home is by making Paradise home again. Rebuilding a place that people want to call home is honoring the people that lost their lives, because we’re recreating what people loved.

I think the biggest thing for people who haven’t been following Paradise closely is to know that we’re not gone. We are rebuilding. We are a strong, resilient community.

We were able to surround ourselves with like-minded people who were determined to rebuild. People showed up from around the country to help us. We fed off each other and we lifted each other up during the hardest times. That’s what helped motivate us and get us through. The way humanity showed up was our big motivator.

When the Lahaina fire happened, Paradise sprung into action within hours. Our Rotary Club had a donation page set up. People in Paradise were donating money, asking what they could do. We were communicating with leaders on Maui, asking how we could share what we learned.

I see a long-term relationship between Paradise and Lahaina. We can offer experience. And just be that voice that says, “We understand you’re having a crap day, and that it came out of nowhere. Three years later, you’re having a rough day? We get it. You don’t have to explain yourself. We just get it.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline 5 years after the Camp Fire, a survivor reflects on Paradise’s recovery on Nov 8, 2023.

The escalating plastic pollution crisis and inefficiencies in the plastic recycling system have turned many…

The post Demystifying Chemical Recycling: An Emerging Solution or a New Set of Challenges? appeared first on Earth911.

Flooding occurs when water submerges land that is typically dry. That water can come from a variety of sources, such as rainfall, a storm surge or high tide, a river overflowing its banks, a dam bursting or snow or ice melting. Some types of flooding can be beneficial for people and ecosystems. When rivers gradually overflow their banks during the wet season and spread into their natural flood plains, this can create habitat for animals and make the soil more fertile for agriculture. The three most ancient human civilizations — ancient Egypt, ancient Mesopotamia, and the Indus River Civilization — all grew up around floodplains. However, flooding can also be extremely devastating. What many calculate was the deadliest natural disaster on record was a flood: the 1931 Yellow River or Huang He flood in China that killed 850,000 to 4 million people and displaced 80 million.

Floods are the most common type of extreme weather event in the U.S.: Between 2000 and 2021, a flood occurred in the country every eight out of 10 days, on average. They are also the second most widely dispersed weather disaster worldwide after wildfires. In the U.S., they are the most expensive natural disaster and the second deadliest after heat waves. Floods can be dangerous because people often overestimate their ability to drive or walk through floodwaters. In the U.S., in fact, driving or walking in floodwater are the No. 1 and 2 highest causes of flood drownings. As flood risk increases due to the climate crisis, it is more important than ever for individuals and societies to be aware of the dangers of flooding and take steps to protect themselves.

There are several types of flooding. Which one you have to look out for will often depend on where you live and what time of year it is.

River, also known as riverine or fluvial flooding, occurs when the amount of water entering a river or stream exceeds its existing channel, causing it to overflow its banks. These types of floods are the most common, and are part of the natural water cycle of many river ecosystems. Rivers can overflow because of heavy rainfall from a tropical storm or a series of thunderstorms, the combination of rainfall and snowmelt in the spring, when melting ice forms a natural dam or if a human-made dam or levee breaks. The devastating Yellow River flood is an example of this type of flooding. The disaster was caused by a trifecta of snow melt, heavy rains and seven tropical-style storms in a row and flooded an area of dry land bigger than England. Another historic riverine flood was the Mississippi flood of 1927, when heavy spring rain caused the mighty river to overflow its banks from Illinois to Louisiana. At its worst point, the flood created a temporary sea 75 miles wide and forced a million people — or around one percent of the country’s population at the time — to flee their homes.

Pluvial flooding occurs when excess rainfall generates flood conditions on its own without adding to a body of water that then overflows. These types of floods can happen anywhere, even if there is no river or lake nearby.

Surface water flooding is a type of pluvial flooding that occurs when rainfall overwhelms a drainage or sewer system. When this happens in a city, it is called urban flooding. The amount of concrete in cities means that rainfall is not absorbed and so runs off into storm drains that can be more quickly overwhelmed. This type of flooding tends to be gradual and shallow — around three feet deep — so it is less dangerous than other types of floods but can still cause damage.

A flash flood occurs when a lot of water moves on to dry land very quickly. Typically, this happens because of heavy rainfall in an area during a less than six-hour time span. Flash floods can be either fluvial or pluvial, with the mass of water overflowing an existing stream or river or filling a dry street, canyon or creek bed. They can also be caused by a dam failure or the sudden removal of a natural river blockage like an ice jam. Debris are often caught up in the fast-moving torrent, creating another hazard. Because they move so quickly and are hard to predict, flash floods are the most dangerous kind of flooding. One example was the Johnstown Flood of 1889, when heavy rain burst a dam near the town of Johnstown, Pennsylvania, driving a wall of water towards the town that was as high as 40 feet. The disaster killed more than 2,000 people, with some bodies swept as far as Cincinnati.

Coastal flooding occurs when ocean water overrides the shoreline beyond the usual high-tide mark. This can happen because of a tide 1.6 to 2.1 feet or more above the average high tide — a type of flooding referred to as nuisance or sunny day flooding — or because of a storm surge or tsunami. A storm surge is caused by a tropical storm or hurricane, while a tsunami is a large wave displaced by an underwater earthquake or volcanic eruption. Storm surges are one of the most deadly and damaging impacts of a hurricane. A storm surge was one of the main factors behind Hurricane Katrina’s more than 1,800 death toll and why Hurricane Sandy had such a large impact on New York and New Jersey. The deadliest tsunami in history was the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004, which was triggered by a 9.1 magnitude earthquake off the coast of Sumatra in Indonesia. Near the epicenter, in northern Sumatra, the flooding reached three miles from the coast. Around 25 million people died in the disaster.

A flood can devastate a community within hours, but its effects and dangers can linger long after the initial deluge.

Floods can be deadly during the first rush of water as people are swept away. Adults can be knocked off their feet by just six inches of fast-moving water, while 12 inches can sweep away most cars and two feet can carry off a truck or SUV. People may also be killed or injured by debris or electric shocks when flooding damages power infrastructure. In the longer term, floods leave behind damaged buildings and roadways, and people can injure themselves on hazards like broken glass or exposed nails when they return to clean up. Flood waters can also spread chemical contaminants like pesticides or fuel or raw sewage that can harm human health and cause outbreaks of water-borne diseases like cholera or typhoid, especially if communities have to wait a long time for access to clean water. Flooded debris can also be an ideal growing environment for unhealthy molds. Flooding killed an estimated 102 people in the U.S. in 2022 and 7,398 people worldwide. Around two-thirds of those deaths were in Asia, at 4,755, with the next highest amount in Africa at 1,768.

Floodwaters can carry buildings and bridges off their foundations and wash away roads or other transportation infrastructure. This damage forces many people to flee their homes. The historic monsoon flooding in Pakistan in 2022, which drowned a third of the country underwater, displaced almost 8 million people. Flooding can also knock out power or internet and phone service, making it harder for people to stay safe or resume work in the aftermath. The excess water can also drown crops, harming agriculture. In Pakistan, again, the 2022 floods rendered almost half of its cotton crop useless. Floods can also disrupt other industries like fishing, healthcare and tourism. In 2022, U.S. businesses lost a combined total of 3.1 million days of operation because of flooding. This means that floods can have major economic impacts on affected countries, some of which may take years to recover. The global economy lost a total of $82 billion in 2021 because of flooding.

Smaller, seasonal floods are a natural and essential part of many river-based ecosystems. During the rainy season, these floods create habitat in the form of seasonal wetlands and are an important part of the lifecycle of certain species like willow and sturgeon. They also benefit human communities by fertilizing the soil by spreading river sediment, refilling groundwater deposits and preventing larger, more destructive floods. However, flooding can disrupt wildlife and ecosystems as well. Flooding brought on by record rainfall in Vermont in summer 2023 washed beavers out of their dams, some of whom were then struck by cars. Floods can erode river banks and dump more sediment into the water, where the nutrients it contains can encourage harmful algae blooms. Through a process called sedimentation, the debris can harm riparian ecosystems by clogging streams and suffocating wildlife.

Floods have both immediate causes — such as storms or dam bursts — and long-term influences that can make a flood’s impact worse.

In the short term, floods are often caused by heavy rainfall, either in a short burst of intense rain or over an extended period of time. When the ground or existing bodies of water can no longer absorb the excess water, it has nowhere to go but dry land. There are certain weather events that are especially associated with flooding. Tropical storms — which typically hit the U.S. in the summer and autumn — can cause flooding both by triggering a storm surge and by dumping rain as they make landfall. Atmospheric rivers — narrow bands of moisture that travel through the atmosphere — are another type of storm associated with flooding. These are more common in California, the Pacific Northwest and Alaska during winter. A series of intense atmospheric rivers drenched California in late 2022 and early 2023.

Another major cause of flooding is related to the seasonal forming and melting of ice and snow. As snow melts, it saturates the soil much like rainfall. If it overwhelms the carrying capacity of the soil, as well as nearby waterways, flooding occurs. Ice jams take place in winter and spring when cold temperatures freeze a river. The jam can cause flooding upstream as the flow of water backs up until it bursts or melts, suddenly causing flash flooding downstream. Snowmelt and ice jams can fuel each other, as runoff from melting snow can put more pressure on river ice, creating a jam.

Dams and levees keep massive amounts of water at bay. By one estimate, the world’s large dams store a combined 1,679 to 1,991 cubic feet of water. If they all burst, they would release enough water to cover around 80 percent of Canada under three feet. While this is unlikely to happen, a single dam break can devastate a community. Sometimes, there is a weather-related trigger to a dam or levee failure. This is what happened during Hurricane Katrina in 2005, when water overtopped or caused levees and stormwalls to fail in more than 50 areas, flooding more than 80 percent of New Orleans. In another, more recent example, heavy rainfall in Libya in September 2023 caused two dams to fail, unleashing a wall of water that killed more than 11,000 people. At other times, a dam break can occur purely because of a structural or engineering error. This is a growing concern as the tens of thousands of large dams built in the 20th century continue to age. The UN estimates that by 2050, the majority of the world’s population will live below one of these dams.

As industrial capitalism has transformed the planet, it has made flooding more likely and dangerous in many ways. One major way is through land-use change. Deforestation and the clearing of natural landscapes gets rid of vegetation that would otherwise help slow and channel the rush of precipitation. Urbanization and other forms of development then replace that vegetation, and the soil beneath it, with concrete roads, sidewalks or parking lots that are less porous to rainwater. Urban drainage systems also channel this water more rapidly into streams, increasing flooding. At the same time, more and more human developments are expanding into natural floodplains and wetlands. Since 1985, overall human settlements have increased by 85 percent while developments in the locations most at-risk for flooding have increased by 122 percent.

These changes are occurring at the same time as the burning of fossil fuels warming the atmosphere, increasing the risk of flooding in many ways, from more intense precipitation, to sea level rise, to more rapid snow and ice melt. While the overall number of floods is not necessarily increasing, it’s likely that the most extreme river floods are becoming more common, even as more moderate river floods decrease. In the U.S., the Climate Science Special Report found that flooding was becoming more common along the Mississippi River, in the Midwest, and in the Northeast. In its most recent Sixth Assessment Synthesis Report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) said that as the climate continues to warm in the near future, the panel had high confidence that flooding would increase in coastal and low-lying areas and that there would be more floods related to mountain glacier melt. In addition, it had medium confidence that higher precipitation would lead to more local floods. Flood risk in the U.S. is expected to increase by more than 25% by 2050.

When floods do happen, they don’t impact everyone equally. Communities that are poorer or otherwise marginalized tend to suffer more. In U.S. cities, low-income communities or communities of color tend to be hardest hit during flooding, since they tend to live in lower-lying areas with less vegetation to act as a buffer. Poorer urban residents are more likely to rely on public transportation and so cannot evacuate as easily as wealthier people with private vehicles. Hurricane Katrina is one example: the storm did much more damage to Black neighborhoods in New Orleans than white ones, partly due to historical patterns of discrimination that relegated Black residents to lower, swampier areas farther from public transit access. The climate crisis is set to only exacerbate these differences — Black Americans will be disproportionately impacted by greater flood risk by 2050, one study found. Globally, many low-lying or island nations that released relatively few greenhouse gases into the atmosphere are nevertheless extremely vulnerable to climate-fueled flooding. In Bangladesh, for example, a low-elevation country located on a river delta, almost 60 percent of the population is at risk from flooding, more than any other country in the world. Climate change is expected to increase the flow of its rivers by 36 percent in a high-emissions future and 16 percent in a low-emissions future by 2070 to 2099. Yet currently it only contributes 0.4 percent to global greenhouse gas emissions.

The relationship between increased global temperatures and increased flooding isn’t as straightforward as the relationship between global heating and more frequent and extreme heat waves. Instead, the warmer atmosphere interacts with the climate system in many different ways to exacerbate the risk of different types of floods.

The atmosphere can hold about 7 percent more moisture per degree Celsius that it warms. Since global temperatures have risen on average 1.1 degrees Celsius above the 1850 to 1900 average, the air would in theory be 7.7 percent wetter now. This means that, when any weather system forms, whether it be a major tropical cyclone or small local thunderstorm, it has more moisture available to it. These extreme rainfall events increase the risk of flash floods that contain more water and form in even less time. During September of 2023, for example, record rainfall brought intense flooding to New York City. A study found that the climate crisis made the type of storm behind this event 10 to 20 percent wetter than it would have been in the 20th century.

The climate crisis is also increasing the chance that tropical storms intensify into more powerful Category 4 and 5 hurricanes. Stronger storms tend to hold more moisture. A 2018 study found that global heating made Hurricanes Katrina, Irma and Maria five to 10 percent wetter than they would have been without it, and that future warming would have made them 15 to 35 percent wetter still. Another example is 2017’s Hurricane Harvey, which dumped as much as 40 inches of rain on Houston in three days, making it the wettest storm in the U.S. in almost 70 years. That rainfall was made at least three times more likely by the climate crisis, and, if the world warms two degrees Celsius by 2100, similar deluges could become three times more likely again.

The ocean is around seven to eight inches higher than it was at the start of the 20th century, as higher temperatures have melted glaciers and ice sheets. Sea level along coastal areas is expected to rise at least another eight inches by 2050 and potentially 20 to 40 inches by 2100. Certain areas, such as the U.S. Gulf Coast or New York City, are sinking at the same time through a process known as subsidence, increasing the impact of rising tides. Sea level rise can increase coastal flooding in two major ways. First, it can lead to more extreme storm surges, because the inrushing water starts from a higher point. But even without a storm, it can lead to higher high tides, increasing the frequency of nuisance or sunny day flooding. In the U.S., the frequency of high-tide flooding has more than doubled since 2000, and some places could see these floods 25 to 75 days a year by 2050. Sea level rise is especially a problem for low-lying islands like Tuvalu or the Maldives. By 2050, some of these islands could become uninhabitable as higher tides increase nuisance flooding and seep into the groundwater, contaminating it via a process called saltwater intrusion.

The climate crisis can also increase flood risk by accelerating the melting of mountain snowpack and glaciers. Earlier snowmelt is increasing runoff and flood risk in the U.S. West, for example. Another hazard is the melting of alpine glaciers. The World Glacier Monitoring Service found that their reference sample had lost a combined almost 82 feet of water between 1970 and 2020. As they melt, these glaciers form lakes, which have increased their number, volume and area by around 50 percent each since 1990. This is a problem, because these lakes are susceptible to something called a glacial lake outburst flood, which can be triggered by factors like dam breaches, earthquakes, heavy rains or avalanches. A study published in early 2023 warned that 15 million people were at risk from these types of floods, especially in the Himalayas and the Andes. Eight months later, a glacial lake breached a dam in the Indian Himalayas after heavy rains and a nearby earthquake, killing at least 41 and displacing thousands.

While flooding may seem overwhelming, especially in the context of the climate crisis, there are things that people can do to prepare for potential floods, protect themselves and their communities and reduce risk.

The U.S. government has clear guidelines for how to stay safe during a flood. First, you can check your risk through the FEMA Flood Map Service Center. Then you should make an evacuation plan for everyone in your household, including pets, and prepare supplies like non-perishable food and a gallon of water per person or animal per day for three days. If your area is under a flood warning, you should find a safe place to shelter and evacuate if told to do so. It’s important to avoid flood water either on foot or in a car. Even if you don’t get swept away, it could contain dangerous debris, downed power lines, chemical contaminants or disease. Don’t cross a bridge over raging torrents, as the bridge could be swept away without warning. If you end up stranded in a vehicle, stay put. If water starts to enter the car, get on to the roof. If you are in a building that is flooding, move to a higher level but don’t enter a closed attic. Once the flood is over, it’s also important to be careful during the cleanup process. Don’t return home before advised, wear personal protective gear and don’t enter moldy buildings if you have a respiratory or immune condition.

As flood risks increase around the world, towns and cities are taking steps to adapt. According to the C40 group of cities committed to climate action, the best ways urban areas can reduce risk are the following:

1. Stop developing on wetlands or floodplains;

2. Restore natural floodplains and give space for vegetation around riverbeds;

3. Replace impermeable paving materials with more permeable ones;

4. Build small reservoirs to collect rain;

5. Build larger rain-storage tanks underground;

6. Find ways to stop trash from clogging sewers;

7. Fit buildings with rainwater tanks and green walls and roofs to help siphon water;

8. Make buildings safer in especially at risk areas by raising foundations or moving essential functions to higher floors; and

9. Work with regional partners to reduce risks outside the city, such as coastal storm surges.

A major way to reduce large scale risks is by restoring ecosystems that naturally control floods, like wetlands or mangroves. The Billion Oyster Project in New York City is working to restore the Big Apple’s once-famous but now depleted oyster reefs, in part to help protect the city from flooding and sea level rise. It’s also important for cities to study where exactly they are vulnerable and to create early warning systems for residents.

The IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report made clear that every degree of warming increases future climate risks, including flooding, and every degree avoided helps to make them less severe. Limiting warming to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels instead of two degrees could prevent an extra four inches of sea level rise by 2100, for example. However, in order to have any hope of reaching the 1.5 goal, world leaders must act to phase out fossil fuels as soon as possible to halve emissions by 2030 and reach net-zero by 2050. Since deforestation and land-use change contribute both to flood risk and to the climate crisis, preventing the continued destruction development of natural ecosystems can prevent dangerous flooding on both counts.

2023 made the risk of climate-fueled flooding extremely apparent. Over just 12 days in September, 10 countries and territories endured extreme inundations. One of these events was the deadly dam collapse in Libya that swamped as much as a fourth of the coastal city of Derna. Scientists calculated that the rainfall that triggered the event was made as much as 50 times more likely by the climate crisis. Derna’s muddy wreckage offers one picture of the future if world leaders decide to keep pumping fossil fuels into the air and fail to repair or adapt infrastructure to account for the increased risk.

But there are glimpses of other possible futures. In Seoul, urban planners decided to take down a 10-lane highway and allow the Cheonggyecheon Stream beneath it to flow in the open again. This provides protection against a one-in-200-year flooding event, but it had other benefits as well, creating a new park drawing more than 50,000 people a day, increasing biodiversity in the area by 639 percent and curbing small particulate matter air pollution by 35 percent. If we work together with natural ecosystems and cycles instead of fighting them, we can create a safer and more vibrant water system for human and non-human life to enjoy.

The post Flooding 101: Everything You Need to Know appeared first on EcoWatch.

Large herbivores like elephants, moose and bison are some of the most recognizable and iconic species on the planet. But they’re not just impressive to look at — their consumption of plant matter and movement throughout the landscape provide great benefits to the ecosystems in which they live.

In a new study, an international team of researchers used global satellite data to map the tree cover of Earth’s protected areas. They found that regions with an abundance of large herbivores in many different settings have a greater variety of tree cover, which is expected to be beneficial to overall biodiversity, a press release from Lund University said.

Megafauna, the largest animals in an area, play an important role in the maintenance of resilient ecosystems rich in many different species, which preserves biodiversity, as well as mitigating climate change.

The researchers looked at the complex relationships between tree diversity in the planet’s protected areas and the number of hungry herbivores.

“Our findings reveal a fascinating and complex story of how large herbivorous animals shape the world’s natural landscapes. The tree cover in these areas is sparser, but the diversity of the tree cover is much higher than in areas without large herbivores,” said Lanhui Wang, lead author of the study and physical geography and ecosystem science researcher at Lund University, in the press release.

The study, “Tree cover and its heterogeneity in natural ecosystems is linked to large herbivore biomass globally,” was published in the journal One Earth.

“In our global analysis, we find a substantial association between the biomass of large herbivores and varied tree cover in protected areas, notably for browsers and mixed-feeders such as elephants, bison and moose and in non-extreme climates,” said Jens-Christian Svenning, the study’s senior author and a professor of ecology at Aarhus University, in the press release.

The team found that a diverse vegetation structure is supported by large wild herbivores. The variety of vegetation is brought about by the animals’ massive consumption of vegetation, as well as the physical disturbances their foraging creates. This creates a rich habitat for numerous other species.

Wang said the findings point to the necessity of integrating large herbivores into conservation and restoration plans, both for their sake and for the essential role they play in influencing biodiversity and shaping landscapes. The research team argued that these contributions have not been adequately taken into account within the framework of ecosystem restoration and sustainable land management.

“At a time when global initiatives are intensely focused on combating climate change and biodiversity loss, our findings highlight the need for a broader and more nuanced discussion about ecosystem management and conservation measures. It is of utmost importance to integrate understanding of the ecological impact of megafauna into this,” Wang said in the press release.

More large herbivores living in the wild are needed around the world in order to achieve the restoration of thousands of square miles of ecosystems that 115 countries agreed to as part of the United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2021-2030).

“I believe that we will need to protect and conserve large herbivores to achieve the UN goals. Megafauna are crucial for tree cover, which in turn promotes carbon sequestration and a diversity of habitats,” Wang added.

The post Large Herbivores Like Bison, Moose and Elephants Contribute to Tree Diversity, Study Finds appeared first on EcoWatch.

A new report from Wrap, a climate action NGO, finds that despite making gains in lowering their carbon impact, such as reducing carbon impact and water usage per garment, fashion companies’ efforts are being canceled out by increased production.

The Textiles 2030 Annual Progress Report reviewed brands that had signed up to Wrap’s voluntary Textiles 2030 initiative, in which participating businesses aim to reduce greenhouse gas emissions of new products by 50% and reduce the aggregate water footprint of new products by 30% compared to levels measured in 2019.

According to the report, participating brands reduced carbon impact by 12% and water usage by 4% per metric ton from 2019 to 2022. Wrap noted these improvements happened because of actions such as reusing and recycling clothes at higher rates.

Yet textile production and sales has increased 13% for the participating businesses, as the average person in the UK purchases about 28 new pieces, or 8 kilograms (17.6 pounds) of clothing per year, Wrap found.

Overall, the 26 participating companies, including major retailers like AllSaints, ASOS, Boohoo, Gymshark, Primark and Urban Outfitters, had only a 2% reduction in total carbon impact from 2019 to 2022. Total water usage was actually up overall by 8%. Participants totalled 3.1 million cubic meters of water consumption in 2022, or enough water to supply 53% of the global population with drinking water for an entire year.

“If we hope to get anywhere near achieving the critical goals of the Paris Agreement, we must get serious about textiles and everyone has a role to play,” Catherine David, director of behaviour change and business programmes at WRAP, said in a statement. “We need sustainable design, sustainable business models, and more sustainable ways of buying and using clothes from more businesses. But production is clearly the key issue, and the onus is on businesses to make preloved part of their portfolio, so it’s accessible, easy and fun.”

Wrap noted that businesses have a critical role to play in reducing consumption, designing for longevity, recycling materials and developing more circular business models that incorporate actions like repairing and renting clothing.

But consumers will also need to adopt more sustainable shopping habits, David shared. According to the report, just 9% of products sold by retailers were “preloved.”

“We buy more clothes than any other nation in Europe. Our research shows that a quarter of most wardrobes go unworn in a year and nearly a quarter of us admit to wearing clothes only a few times,” David explained. “Moving into winter is the perfect time to look through our wardrobes — wear what we have and consider whether it’s time to let something go. You can donate, sell, or give clothes away — it all helps them move around the economy and reduce the amount produced.”

The post Fashion Companies Show Progress in Lowering Carbon Impact, but Increased Production Makes It a Wash appeared first on EcoWatch.

This is the third in a series of five articles that help you find ways…

The post Good, Better, Best: Cutting Carbon From Home Heating and Cooling appeared first on Earth911.

The Komati coal-fired power plant, located 88 miles east of Johannesburg in South Africa’s coal heartland, has been called the flagship of the country’s budding energy transition. At its peak, the facility, which came online in 1961, produced 2 percent of the country’s power supply. It also supported thousands of people, from miners digging nearby seams to hawkers selling bananas by its front gates. Yet its owner, the state company Eskom, retired the plant in October 2022 after deeming the repairs needed to keep it running cost-prohibitive. Instead, it chose Komati for a different sort of makeover.

A $497 million project financed by the World Bank will, over the next five years, dismantle the plant and surround it with solar panels and wind turbines, a battery array, a green-jobs training center, and a factory that will employ hundreds of workers building community microgrids. President Cyril Ramaphosa hopes Komati will not only lead his country’s emergence as a clean energy heavyweight but show how to do so equitably and with the guiding input of communities and labor. Eskom calls Komati one of the largest efforts in the world to decommission and repurpose a coal plant, and says it could become a “global reference on how to transition fossil fuel assets.”

But when Malekutu Motubatse visited a nearby village in September, he found a ghost town. Motubatse, who represents some 35,000 miners and others as regional chair of the National Union of Mineworkers, says the closure cost at least 1,000 contractors their livelihoods and crashed the local economy. “People are demoralized, people are hungry,” he said of the 4,000 or so residents. “You can’t just close down a power station without an alternative. People can’t eat promises.” A recent report on Komati, commissioned by Ramaphosa, backs him up, saying Eskom wrongly shuttered the facility before new work opportunities were in place. But with four more coal plants scheduled to close in the area by 2030, Motubatse fears more harm to workers and communities lies in store.

If Komati is the flagship of South Africa’s plan to transition to a clean energy economy, it’s also an early indicator that things are off to a choppy start. For the last two years, the country has led a group of developing nations that are working with the Global North to prove it’s possible to accelerate this process while buffering workers and communities from the shakeup. In 2021, South Africa became the first to formalize this mission in a policy plan, signing an $8.5 billion deal with a cluster of G7 nations called the Just Energy Transition Partnership, or JETP. The program’s guiding logic is that many emerging states want to grow on a sustainable path but need cash to do it fast enough to benefit the climate.

JETPs are designed to support them with a burst of focused investment. The basic structure is that a group of rich nations — including, for example, the United States — pledges money to a developing partner, which comes up with a compendium of projects that it thinks can hasten its energy evolution and deliver specific emissions reductions. Partners review the list and match funding to projects over a window of three to five years. Ideally, they should unlock billions of dollars more in private-sector investment. It’s not yet known how well this will work, but that hasn’t stopped Indonesia, Vietnam, and Senegal from signing similar deals over the last two years. More announcements could be coming at COP28; India, Nigeria, and Kazakhstan are some of those rumored to be in the hunt. China’s signaled interest in financing similar programs. Last week, President Xi Jinping announced roughly $100 billion in climate financing to spur clean energy projects abroad, in an initiative that boosters say has some resemblances to the JETP.

No one expects these efforts to go smoothly. Even in rich countries energy infrastructure is notoriously slow to change, with transitions measured in decades rather than years. Experts have already observed frictions between the Global North and South — from squabbles over financing to differing visions of justice — and say this is slowing the flow of money and deployment of real-world projects.

In some cases, these frictions are evidence of tough, pragmatic negotiations; in others, they reveal deep divisions that could slow or even derail a country’s participation in the program. “This is your credibility,” Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan, Indonesia’s coordinating minister and its top JETP negotiator, snarled at G7 partners in a May interview with Bloomberg. “We don’t lose anything if the deal doesn’t materialize.”

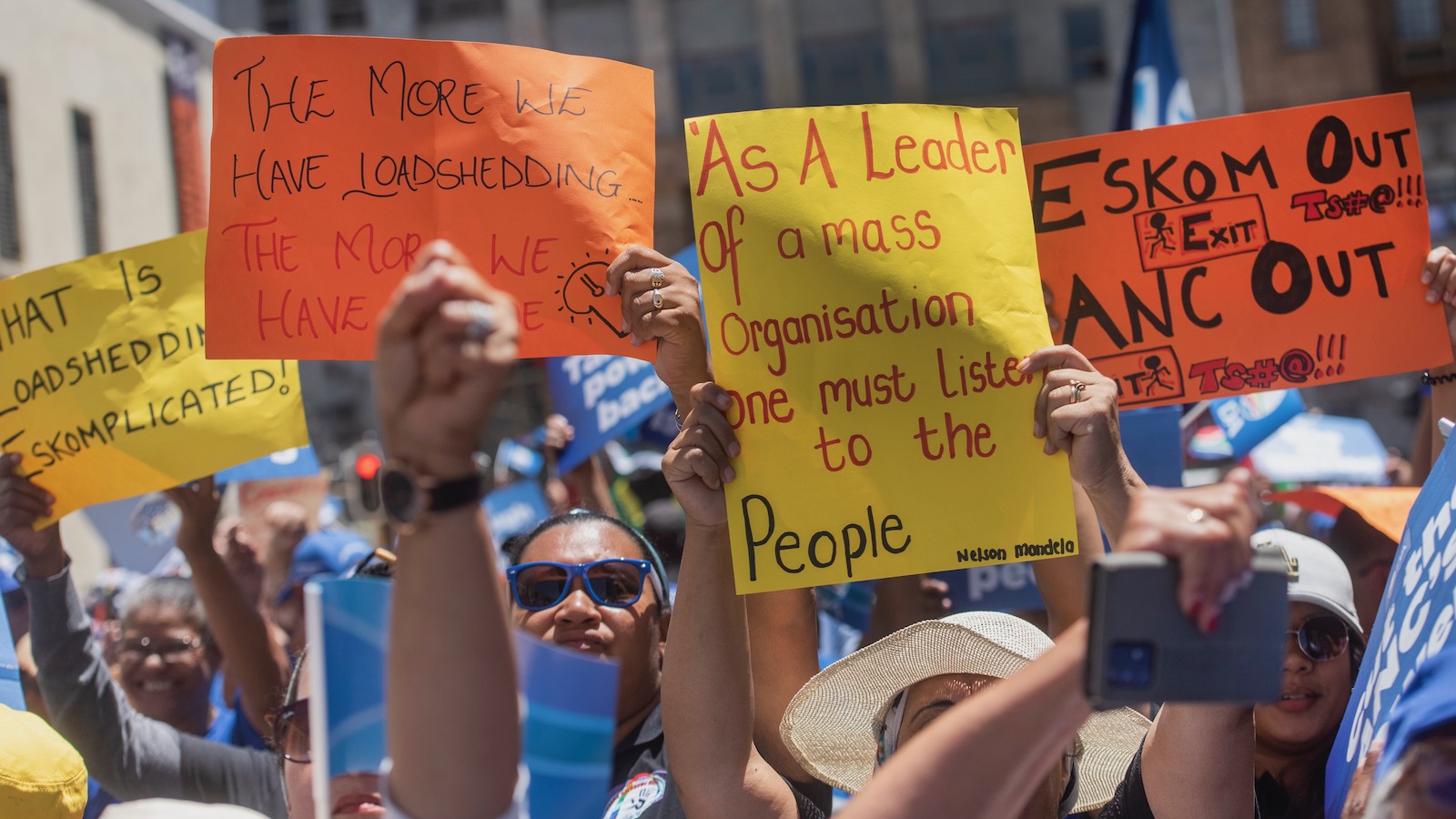

South Africa’s energy transition was driven by a combination of factors: a sense that its economy was overdependent on fossil fuels, direct exposure to climate impacts, and perhaps most immediately, practical necessity. Not only does the country generate 80 percent of its power from coal, but half of its plants are more than 40 years old and require intense upkeep that one expert likened to life support. As energy demand increases, this wheezing fleet is increasingly incapable of keeping up, and electricity gets rationed. This year has seen particularly severe stretches during which South Africans experienced up to 12 hours of power outages a day.

In towns like Komati, the local power station, also called Komati, is the axis around which the local economy revolves. Nationally, the shrinking coal-mining industry only employs about 80,000 workers, but the tally of everyone whose livelihoods are directly or indirectly tied to that fossil fuel — including families — totals two million to four million people by one estimate.

Ramaphosa, a former general secretary of the National Union of Mineworkers who also played a key role in negotiating the end of apartheid, has said the energy transition could simultaneously advance South Africa’s climate, economic, and social justice goals. Analyses cited by his Presidential Climate Commission say the shift from coal to renewable energy could create up to 1.4 million more jobs than it eliminates. Third-party assessments suggest that developing new industries in electric cars and green hydrogen could create millions more jobs. In an October 2021 public letter, Ramaphosa said the country would begin this long-term evolution by converting roughly 10 retiring coal plants into nodes of green infrastructure, featuring solar, wind power, and energy storage — starting with Komati.

South Africa could do even more, Ramaphosa wrote, if rich countries chipped in. A month later, at COP26 in Glasgow, it became clear what he was talking about when South Africa signed its JETP. Success in South Africa, said European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, would offer a “template” for others in the developing world.

Two years in, there’s little to show for it. Less money is moving than expected, said Leo Roberts of E3G, a think tank focused on addressing climate change, and there’s no physical infrastructure or up-and-running programs to evince a transition in progress.

One hangup is money. When South African officials read the fine print on the $8.5 billion deal they’d signed, they found just 4 percent came in the form of grants that don’t have to be repaid. The remaining 96 percent looked much like the loans South Africa could have obtained on its own, and some was money rebundled from previous programs, said Roberts, E3G’s program lead for fossil fuel transition.

This skews the funding package toward capital equipment. Because loans must be paid back, lenders favor investments with high returns. Solar and wind farms qualify, said Roberts, as do grid upgrades to some extent. Activities that emphasize equity, like training workers or supporting small businesses, don’t have direct investment returns, and so are less likely to get funded.

But it would be a mistake to view such programs as charity, said Mandy Rambharos, a former Eskom official who helped launch its energy transition program. “The return on investment is not in terms of financial benefit, but social license to operate,” said Rambharos, now vice president of global climate cooperation at the Environmental Defense Fund. “There is a return: Otherwise your [infrastructure] projects are not going to fly.”

Perhaps in response to this concern, last month the Netherlands and Denmark announced about $180 million in grants for South Africa’s JETP, Bloomberg reported.

Recent events have revealed domestic discomfort with the energy transition, too. In the towns near Komati, community leaders have fumed that they aren’t seeing credible plans for creating jobs. Mineworkers have accused the government of selling out to the West and institutions like the International Monetary Fund, prioritizing climate goals while ignoring devastating unemployment in coal country. (The official unemployment rate in Mpumalanga province, which produces 80 percent of South Africa’s coal, hit 38.5 percent this year.) In July, the national electricity czar — whom Ramaphosa named in March to fix the country’s crippling power shortages — said the proposed energy transition was harming both people and the grid. “If I had my way, we’d go and restart Komati,” he said. “We have international obligations but, I’m sorry, we have an obligation to the South African people.” Those words gave heart to one local leader near Komati, who said, “The plant should be opened, because coal is the future.”

As Eskom held public-engagement meetings in Komati town this summer, a number of locals blasted them for paltry training programs and distant promises of opportunity. At one event, recorded by journalist Elna Schütz, company representatives seemed shaken by the withering critiques. “What did we miss?” blurted one official against the rising voices. “Help us understand.”

In July, Ramaphosa sent a special delegation to Komati to assess progress. Its September report said the project, while flawed, does have green shoots. According to Eskom, which did not respond to a list of questions from Grist, a facility that can produce container-sized solar microgrids, each capable of powering 50 rural homes, is ready. A green-jobs skills center has begun training its trainers. But to union rep Motubatse, these might as well be on Mars. “There is nothing there,” he said. “There’s no way to go there and find work.”

South Africa is hardly the only country having headaches. Indonesia is involved in multiple early-stage energy-transition programs, including a $20 billion JETP it signed in November 2022. Outside analysts say these efforts have produced little besides paperwork. A major investment plan, expected in August, has been pushed to later this month. Last November, the country teamed with the Asian Development Bank to devise a financial plan to retire a 660-megawatt coal plant up to 15 years early. It’s hoped this could become a test case for shuttering similar generators in the region. But no financing has been announced to underwrite the proposal.

A key problem is that Indonesia’s coal plants, unlike South Africa’s, are relatively new. Many have locked in 20- or 25-year contracts with the state to buy their electricity and just begun their lives as profitable assets. One of the JETP’s core missions is to eke out financial deals that retire these facilities early. Putra Adhiguna, an analyst with the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, is unsure what kind of offer could compel an owner to abandon that kind of moneymaker. “There’s just no sheer financial rationale to do this,” he said. One Asian Development Bank official has likened it to persuading someone to leave their apartment before the lease is up.

Behind this has loomed an even thornier issue: Indonesia is planning a massive coal buildout. The country’s volcanic origins have blessed it with some of the world’s biggest deposits of nickel and aluminum, two elements essential to batteries. But smelting them takes heat. Industrial producers are building fleets of private, or “captive,” coal plants that generate electricity, heat, or both. Tiza Mafira, Indonesia director at the Climate Policy Initiative, estimates that the JETP, if successful, could retire up to 5 gigawatts of coal-generated power. But the potential pipeline of captive facilities is quadruple that. “To invest in an early coal retirement knowing there’s more in the pipeline than you’ll retire is not exactly great,” said Mafira.

But blame can cut both ways, she added. In their eagerness to fund renewable energy, she said, G7 partners have shortchanged the amount devoted to coal retirements, causing frustration on the Indonesian side.

Late last month, Reuters reported that Indonesia will propose one solution to break the impasse: simply excluding the captive coal plants from the JETP scheme.

Then there’s the two newest JETP implementers, Vietnam and Senegal, where the energy transition has caused friction in different ways.

In recent years, Vietnam has experienced a wind and solar boom that’s the envy of Southeast Asia. Its success helped seal a $15.5 billion JETP deal with the European Union, United Kingdom, United States, Japan, and others last December. Core goals include writing off 7,000 megawatts of planned coal and increasing renewable generation to nearly half the grid by 2030.

Analysts say this green shift was driven by the tireless work of Vietnamese climate campaigners who — working within the narrow political space afforded by the one-party government — persuaded leaders that renewable energy would benefit the air and the economy. But in the last year, Vietnam has drawn censure from its JETP partners for arresting a half dozen of these advocates, mostly on tax charges that human-rights groups consider baloney. Some of these groups have called on JETP funders to pause implementation until the crackdown ceases.

Senegal’s $2.7 billion (€2.5 billion) JETP, signed in June with France, Germany, Canada, and the broader EU, drew notice for a different reason. Although the deal committed the country to the ambitious goal of getting 40 percent of its power from renewables by 2030, it also affirmed its plans to use natural gas as a transition fuel. (Senegal wants to refashion plants that burn heavy fuel oil to use methane, which the JETP partners claim will reduce greenhouse gas emissions.) Defending this choice, French President Emmanuel Macron promptly stepped in it: “We will allow it to develop its gas resources because gas is a transitional energy,” he said. The comment rankled some in Senegal and elsewhere, as it sounded less like that of a partner and more like that of a former colonizer.

If the gas has European partners gritting their teeth, Senegalese leaders consider it the piece that sealed the deal. The nation’s recently discovered gas fields represent one-fifth of a percent of global resources, according to Rystad Energy, a consultancy. But for politicians eager to expand electricity access and industrialize the economy, they represent a multibillion-dollar development fund. Public opinion surveys and stakeholder engagements suggest many Senegalese support developing the country’s hydrocarbon resources as well as clean energy.

The triumph of the final JETP, argues Secou Sarr, executive secretary of Senegalese NGO Enda Tiers Monde, is that Senegal got to choose its path forward, as developing countries too often don’t. “We are not just passive subjects,” Sarr wrote in a June essay. “We will lead the way in shaping the future of our country.”

It’s too early to judge if the JETP or similar efforts will succeed in fostering a just transition. It’s not too early, though, to make an observation: Nobody’s done this before, and it shows. The U.S. and the U.K., for example, are two countries where the collapse of the coal industry left lasting wounds. Germany is sometimes upheld as a model for green transition, but the ability to transpose that experience to a developing country is unproven.

In South Africa, there is a growing sense that there will have to be learning, and not all of it will be painless. After a September briefing on Komati, South African Environment Minister Barbara Creecy struck a sober note. “If this is not a blueprint for the future,” she said, “we have to learn from this experience what would be a blueprint.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline The West wants to help developing countries transition to renewables. It’s off to a rocky start. on Nov 7, 2023.