Quick Key Facts

- Oil spills occur when crude oil is released into the surrounding environment — particularly oceans — and can threaten marine flora and fauna.

- Spills are typically associated with offshore drilling operations, which drill below the surface of the ocean to access pockets of oil and gas.

- Roughly 706 million gallons of oil enter the ocean every year.

- The Deepwater Horizon BP Oil Spill of 2010 remains the largest marine oil spill in U.S. history, releasing 210 million gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico. More than a decade after the disaster, many marine species in the area are still recovering.

- Animals active near the ocean’s surface are most impacted by oil spills — like seabirds and otters — as well as seals, whales, sea turtles, and many species of fish.

- Along with their environmental impact, oil spills also affect human health and the economies of surrounding communities.

- Booms, skimmers, dispersion, biological agents, and burning are among the more common methods of cleaning up an oil spill.

What Is Oil?

Crude oil or petroleum is a liquid fossil fuel. We use it to generate electricity, heat our homes, and fuel our cars. Petroleum products supply about 35% of energy in the U.S., with transportation accounting for the largest portion. Burning fossil fuels like oil releases greenhouse gases into the atmosphere that drive climate change.

While oil is also found under land, much is stored under the ocean floor. This oil was formed from deposits of plankton that decayed over time, and under intense heat and pressure, turned into compounds of hydrogen and carbon. This raw material for oil travels upward over time to where there is less pressure, until it is stopped by impermeable rock and then settles in reservoirs under the sea bed.

Oil is acquired by drilling into the ocean floor to extract it from the rock in which it’s stored. It’s pumped out, then transported by pipes, ships, trains, or trucks to refineries that process the oil so it can be used to create a variety of products like plastics, gasoline, and other fuels. In this whole process of drilling and transporting, oil can be spilled into the surrounding environment. An estimated 706 million gallons of oil enter the ocean every year, which has massive human and environmental impacts.

Offshore Drilling: The Basics

Oil spills are typically associated with offshore drilling operations, which access these underground pockets of oil and gas by drilling through the ocean floor. In 2021, 15% of crude oil was procured from offshore drilling operations, as was 2% of gas.

Offshore drilling is anything but simple. It’s a lengthy process that takes years of construction and hundreds of million dollars to carry out. Because coastal waters are public land, fossil fuel companies must first lease parcels from the government in order to drill, which requires navigating the complicated regulation of these natural areas. The operator does an exploration of the area (often through seismic testing) to find oil and gas reserves, then builds mobile offshore drilling units — otherwise known as MODUs, oil rigs, or oil platforms — to dig a well. MODUs are some of the largest human-made structures on Earth and are also used to house workers and store equipment. Oil is pulled from the wells, stored, processed, and then transported to the coast via pipelines. In the U.S., offshore drilling happens mostly in Alaska, the Pacific Coast, and the Gulf of Mexico.

How Do Oil Spills Happen?

It’s not hard to imagine that in the midst of all of these complicated, massive drilling processes, oil can spill into the surrounding environment. These spills can happen anywhere where oil is being drilled, used, refined, or transported, whether it be in oceans, lakes, or rivers. Oil spills can happen naturally in what’s called a petroleum seep, during which hydrocarbons escape and reach the surface of the water due to activity deep inside the Earth (often the erosion of sedimentary rock). However, most large spills are from anthropogenic sources.

We all hear about the most disastrous oil spills in the news, but they actually happen pretty frequently: thousands each year, in fact. Many are small and can happen, for example, when a ship is being refueled. Drilling fluid is also used for lubrication in wells — also known as “mud” — and is supposed to be captured, but often leaks in the process. Large spills are much more disastrous, and come from different places within offshore drilling operations: transport containers, drilling platforms, and oil wells, primarily. They are caused by human error, breaking or malfunctioning equipment, natural disasters like hurricanes or high winds, or deliberate acts of terror or illegal action. A series of oil spills followed Hurricane Katrina in 2005, with 450 pipelines and 100 drilling platforms impacted by the disastrous weather. Oil can leak from a poorly maintained container, or a huge amount can be released when tanker ships rupture or a pipeline breaks, for example.

Abandoned oil wells are another large source of oil spills. Oil wells are shut down by operators when they are no longer profitable, and while the companies are required to remove their equipment and restore the area they worked in, this often doesn’t happen. Wells therefore often remained uncapped and leak oil into the oceans and atmosphere. It’s estimated that 28,232 permanently abandoned wells currently exist in federal waters.

After oil spills, it spreads across the surface of the water and forms what’s called an “oil slick,” the major source of concern in the aftermath of a spill.

Historic Oil Spills

Santa Barbara Oil Spill

This 1969 spill near the city of Santa Barbara in Southern California was the worst oil spill in history at the time. A huge explosion occurred at the drilling site, which is largely attributed to inadequate safety precautions at the site and waivers given by the U.S. Geological Survey that allowed for weak protection of the drilling hole. About 4 million gallons of oil flowed into the Santa Barbara Channel, leaving an oil slick along 35 miles of California coast. The disaster spurred a huge amount of environmental action — the creation of Earth Day is attributed in part to the spill — and new federal policies arose regarding offshore drilling, including requirements for operators to pay for oil spill cleanups.

Amoco Cadiz Oil Spill

In 1978, a crude carrier owned by American petroleum company Amoco containing 69 million gallons of oil hit shallow rocks on the French coast near Brittany due to a mechanical failure of the steering system, coupled with stormy weather. Over the course of two weeks, all of the oil was released in the ocean and 200 miles of the coast was polluted. Millions of invertebrates and 20,000 birds died, and oyster beds in the area were contaminated. Weeks after the incident, millions of dead benthic species — including molluscs and sea urchins — washed ashore.

Atlantic Empress Oil Spill

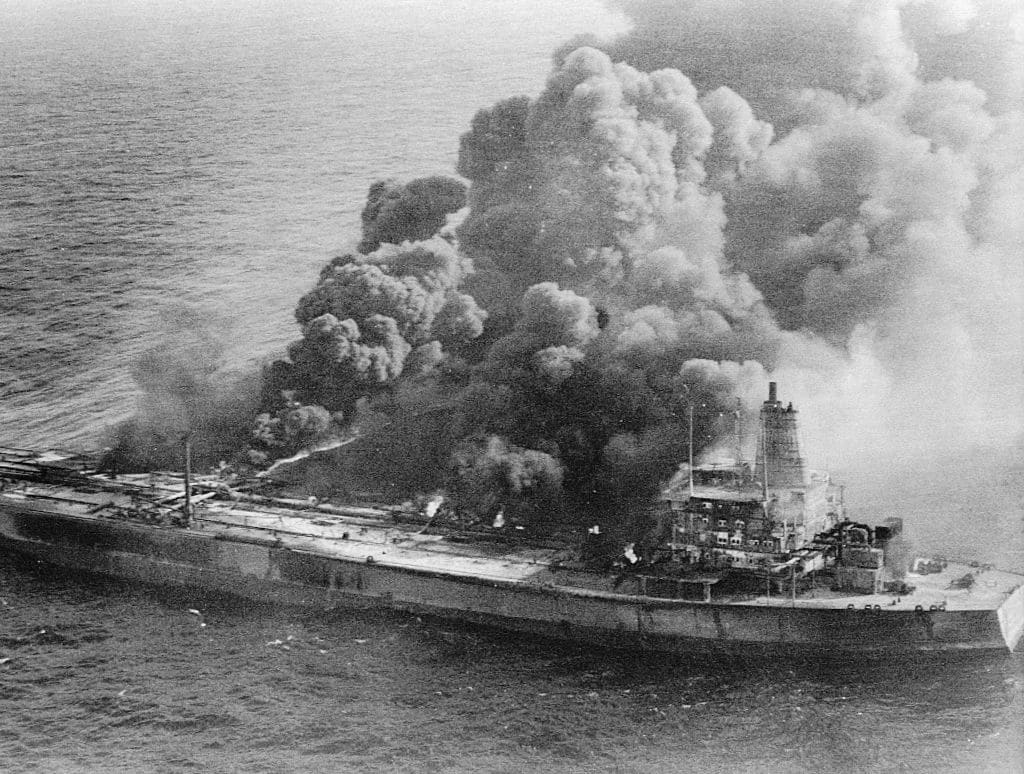

To this day, the Atlantic Empress spill is considered the worst tanker oil spill (specifically from an oil tanker, as opposed to an oil rig or other source) in history, and fifth-largest spill overall. In 1979 off the coast of Trinidad and Tobago, the Greek oil tanker collided with another tanker due to heavy rain and foggy conditions. An estimated 287,000 tons of crude oil was spilled (there are about 305 gallons of oil in one metric ton), 27 people died, and the Empress was still burning a week after the collision.

Exxon Valdez Oil Spill

On March 24, 1989 in Alaska’s Prince William Sound, the Exxon Valdez set another record as the worst oil spill in history at that time. The tanker transporting crude oil ran aground at Bligh Reed and ruptured, spilling eight of its eleven cargo tanks into the ocean. Along the shoreline, 1,300 miles of pristine wilderness were contaminated by 11 million gallons of oil. The spill is remembered for its huge impacts on local wildlife: hundreds of thousands of seabirds, thousands of mammals, and hundreds of bald eagles were killed. Thirty years later, killer whales and some seabird populations still haven’t fully recovered. Various cleanup methods were employed after the spill, including burning the oil, mechanically removing it, and hot-water hosing the shore. However, some of these treatments (especially the hot water) were found to actually be harmful to the environment. After the cleanup effort, only 14% of oil had been removed and 13% had sunk into the ocean — the rest evaporated and degraded over time. To this day, pockets of oil are still present on the scene underground.

Deepwater Horizon BP Oil Spill

The largest marine oil spill in U.S. history, the Deepwater Horizon — often just called the “BP oil spill” — is widely remembered for its devastating impact. On April 20, 2010 in the Gulf of Mexico, an explosion on a drilling platform killed 11 people and caused 210 million gallons of oil to spill into the ocean. Within five days the oil had covered 580 square miles, and within 10 days, 3850 square miles. The oil flowed for 87 days from the Macondo Prospect before it was capped. The spill occurred in one of the most biodiverse marine areas in the world and had a massive impact on the environment. While some species have rebounded, many are still struggling today, including deep-sea coral and spotted sea trout. Preliminary research shows that many dolphins in the area have remained sick, and have a much lower rate of successful pregnancies. Restoration — funded by a $8.8 billion settlement with BP — is still active today.

Environmental Impact of Oil Spills

Oil clings to everything: rocks, sand, plants, and animals. When it eventually stops floating, it sinks below the surface of the ocean and continues to impact species underneath. The seriousness of a spill can be a function of location, habitat, and the concentration and type of chemicals in the oil. Because they aren’t able to disperse as much, spills that happen closest to shore are often the most dangerous — although those that occur far out at sea cover a huge range and thus impact a larger area. Wherever they occur, oil spills have a devastating impact on the natural world.

Disruption to Ecosystems

Clearly, such a huge influx of oil destroys natural habitats in its wake. It coats plants, soaks into the soil and sand, and poisons or suffocates species. When oil floats on top of the water, light can’t penetrate and photosynthesis is prevented, meaning plants that provide food for many underwater species can’t grow. Oil also erodes shorelines and harms vulnerable ecosystems like wetlands. The Deepwater Horizon explosion especially impacted Louisiana’s Mississippi River Delta ecosystem, which provides vital ecosystem services like flood control, and important nesting areas for animals and host birds during migration seasons.

Harm to Animals

Oil floats, so animals close to the surface, like birds and otters, are often impacted. The Exxon Valdez spill, for example, resulted in the death of 250,000 seabirds, 3,000 sea otters, 300 harbor seals, 250 eagles, and 22 killer whales. Similarly, the BP oil spill was fatal to 1 million seabirds, 5,000 marine mammals, and 1,000 sea turtles.

Ocean wildlife is primarily impacted by oiling (or “fouling”) on their external bodies. We’ve all seen an image of a duckling covered in oil, and it’s as deadly as it looks. When oil coats the wings of birds, they are unable to fly and become victim to predators, or can’t flee the scene of the spill. It also impacts the insulating properties of fur for sea otters and other mammals, who then can’t regulate their body temperature and become at risk for developing hypothermia. Other mammals are impacted, too, like whales, dolphins, and seals, whose blow holes get clogged by oil, leaving them unable to breathe.

Oil toxicity impacts the internal body of animals, too. The toxic compounds in oil are poisonous to animals. Many swallow or inhale the oil while cleaning themselves, or when they eat prey that have been coated in it. The oil can damage the immune system and the heart, impact the function of lungs and liver, blind animals, and cause reproductive changes.

Oil spills can affect the population numbers and long-term survival of species as well — especially when, like the BP oil spill, they occur during mating and nesting season. Sea turtles, for example, spend most of their life at sea, but come to land to nest and breed. If damaged by oil, their eggs might not develop properly. Fish eggs and larvae are especially threatened by oil spills. Shrimp and oyster fisheries along the coast of Louisiana were seriously harmed during the BP oil spill, and it took nearly 30 years for fisheries impacted by the Exxon Valdez spill to recover. Even if a species itself isn’t directly impacted by the spill, these population declines impact food chains — if a species depends on prey that have been killed in a spill, they will suffer, too.

Atmospheric Impacts

While it might not be as immediately obvious, atmospheric pollution is another harmful impact of oil spills. During the cleanup efforts after the BP oil spill, for example, the oil was burned off the surface of the ocean, releasing 1 million pounds of black carbon into the atmosphere. Methane — a climate-warming greenhouse gas — is also released in oil spills It often forms alongside fossil fuels in underground reservoirs, so when oil is released, so is methane.

The Issue of Arctic Drilling

Offshore drilling in the Arctic is of particular concern. The Arctic warms at twice the rate of the rest of the world and could be ice-free in the summer by the 2030s, opening the path for more oil and gas exploration. It is among the most remote areas on the planet and would be nearly impossible to clean up in the event of a major oil spill. Emergency responders are not nearly as widespread, environmental conditions make it difficult to transport major equipment out there, and because less than 1% of the U.S. Arctic has been surveyed with modern technology, we do not have very accurate navigational charts of the area. There have been arguments to ban the use and carriage of oil on ships in the Arctic, or to create safe shipping corridors that don’t go through vulnerable habitats. However, in March the Biden administration announced plans to block oil and gas drilling in swaths of the Arctic Ocean and Alaska, while simultaneously approving the highly controversial Willow oil project on the North Slope of Alaska, about 200 miles north of the Arctic Circle, drawing major criticism from environmental groups.

Social Impact of Oil Spills

Along with these serious environment impacts, oil spills also cause harm to humans — particularly those in communities surrounding the spills.

Human Health

Among other harmful substances, crude oil contains volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which can impact both the respiratory system and the nervous system. Workers and volunteers cleaning up the spill have direct exposure to the oil, and community members can still inhale these chemicals as they are dispersed by the wind, or ingest contaminated seafood and water. The BP oil spill was one harrowing example of the impact that oil spills can have on human health. In the months after the disaster, many citizens — especially those that helped in the cleanup — reported symptoms. Research has linked exposure of those who helped with the cleanup in the aftermath of the BP oil spill with increased risk of cancer, long-term respiratory conditions, and heart disease, as well as blurred vision, headaches, and memory loss. Local residents have coined their chronic symptoms after the cleanup — which include diarrhea, rashes, and respiratory problems — “BP syndrome” or “Gulf Coast syndrome,” according to The Guardian. Besides these physical impacts, elevated rates of depression, anxiety, and PTSD have been documented in cleanup workers and volunteers.

Loss of Revenue and Resources

Commercial fishing and tourism — two industries that prop up many economies — can be devastated by oil spills. In the aftermath, beaches and parks along the shoreline close for lengthy periods — and in general, tourists are less likely to want to visit these places and may believe a wider area to be impacted than actually is. In areas that depend on tourism, this can be devastating to their economies. After the BP oil spill, the region’s commercial fishing industry reported $62 million in losses, and the tourism industry $1.5 billion. For tribes and First Nations that depend upon natural resources, an oil spill could be disastrous to the entire fabric of their community and survival.

Oil Spill Cleanups

The response to oil spills is generally fourfold:

- Stopping the flow of oil and protecting areas that might be harmed by it.

- Removing the oil from the environment.

- Recovering and rehabilitating wildlife.

- Restoring the impacted area.

Sensitive locations in particular, like wetlands, nesting areas, and beaches, need to be protected from oil slicks. Some sensitive habitats need very specific cleanup processes so they are not further damaged. It can be difficult to enact cleanups when the spill happens over a wide area, and when it impacts larger animals like whales, which are hard to recover and rehabilitate.

Data collection is an important element of oil spill cleanups. NASA takes satellite and airborne data to locate oil and determine its trajectory. ERMA (Environmental Response Management Application) — which NOAA made available during the Deepwater Horizon spill — is an important mapping tool that uses Environmental Sensitivity Index maps, locations of ships, currents, weather, etc. to aid in cleanup efforts. The U.S. Coast Guard is primarily responsible for oil spill cleanups, as well as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The Oil Pollution Act of 1990 also established that the party responsible for an oil spill can be held responsible for costs incurred in cleaning up and restoring the area.

Cleanup Methods

Oil spills can take many years to completely clean up. Often, several methods of cleanup are employed at once. The type used depends on how much and what type of oil is spilled, where the oil has spilled and its distance from the shore, what species and habitats are being impacted, and whether people live in the area. The following are among the most common methods and technologies, although ultimately, none removes 100% of oil on its own.

- Booms are floating barriers made of plastic or metal. These are strategically placed in the ocean to help contain the oil and slow its spread, especially to keep it away from certain sensitive areas. Booms can be placed around a leaking tanker, or along coastal areas as protection.

- Skimmers are deployed by boats to “skim” the oil off the surface of the ocean, although their viability depends on the thickness of the oil slick.

- Burning — or “situ burning” — is less common, and entails setting the oil slick ablaze.

- Dispersion uses chemical dispersants to break up the oil slick by dispersing it into the water column so that less remains on the surface of the ocean.

- Biological agents like microbes or fertilizers are used to break down oil.

Cleanup efforts are made on the shorelines surrounding a spill as well, using biodegradation agents, burning, and manual and mechanical removal, as well as other methods. Vacuum trucks suck up the oil-polluted water, sorbents absorb the oil like a sponge, and water hoses rinse the oil into the water where it can be collected more easily.

Restoration

Restoration is another important part of oil spill responses. These projects are different from the cleanup itself — beyond merely removing the oil, they entail actively restoring habitats that have been destroyed. Restoration might mean rebuilding a marshland, reintroducing lost species, controlling erosion, or otherwise supporting the ecosystem services and functions that help the ecosystem heal itself. In the aftermath of a spill, a Natural Resource Damage Assessment (NRDA) is completed by NOAA to determine the impacts of the spill and then settle how the cleanup will be paid for. Usually this process is done between the party that caused the spill and government agencies at the state and federal level, as well as tribal agencies.

Takeaway

Oil spills are major environmental disasters that will likely continue as long as our dependence on oil does. A global transition to clean energy would be a necessary large-scale change in order to eliminate oil spills as a threat, although reducing our personal use of fossil fuels is a useful beginning, including driving less, powering our homes with clean energy, and using less plastic.

While offshore drilling is still a reality, responsible choices by operators can prevent deadly oil spills from occurring, such as performing routine inspections of operations, investing in training of workers, and adhering to requirements made by legislative bodies.

Legislative action regarding boat safety and offshore drilling is a proven useful avenue in preventing spills. The 1990 Oil Pollution Act stipulated that all tankers must be double-hulled by 2015. In 2021, the Polar Endeavour collided with a tugboat, suffering a four-foot indentation that penetrated the outer hull of the ship but not the inner, so no oil was spilled. This event shows that safety legislation can be effective at preventing spills, and electing representatives who champion environmental protection is an important tool at our disposal.

The post Oil Spills 101: Everything You Need to Know appeared first on EcoWatch.