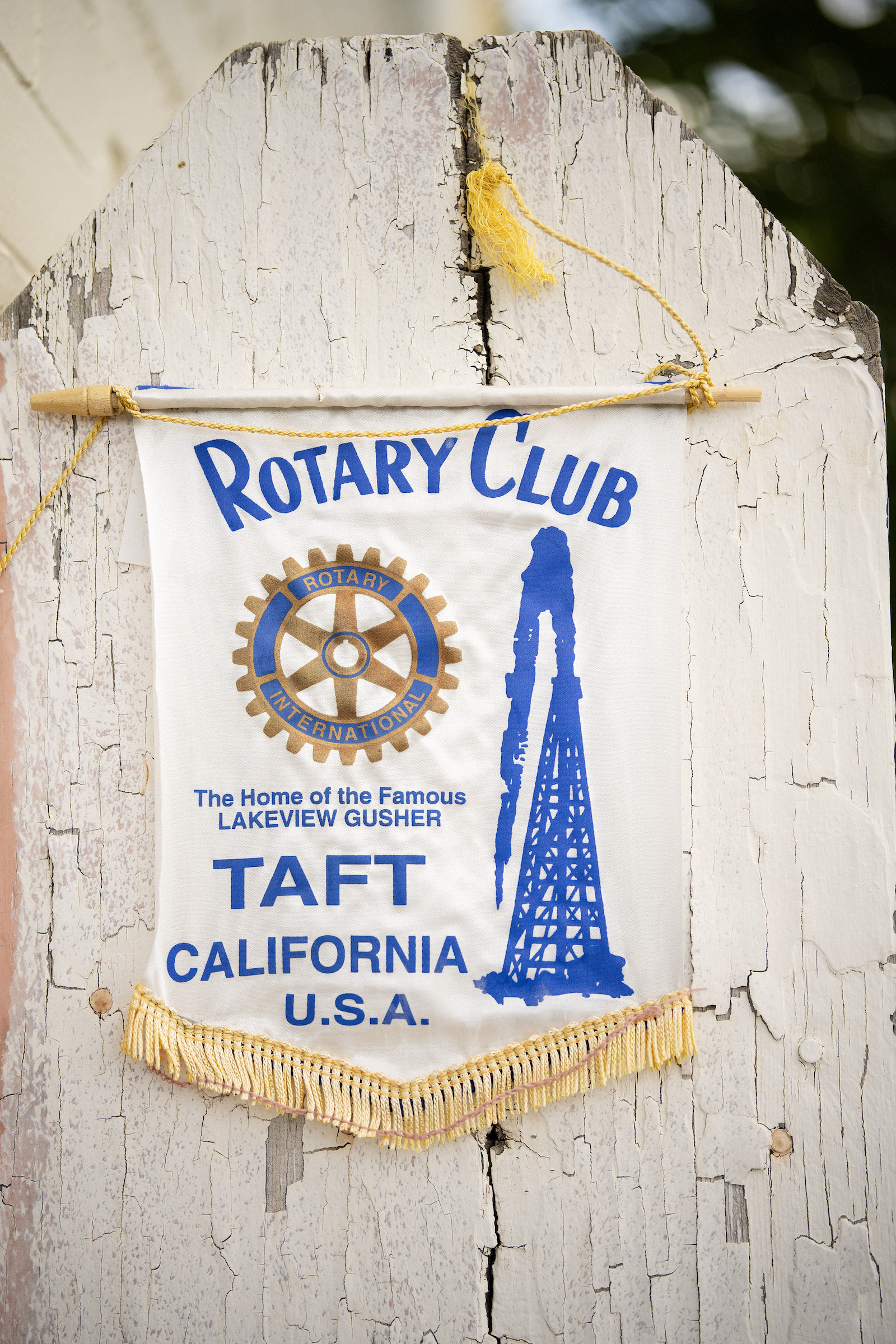

Les Clark III took charge of the West Side Recreation and Park District in 2018, just as the bottom was falling out in Taft, California. The oil pumps that surrounded the town of 9,000 had been nodding up and down for decades, but all at once they froze in place, beams hovering in the air like hammers about to fall. The drilling rigs and service trucks vanished from the winding roads around the town, blanketing it with an unfamiliar silence.

For as long as Clark could remember, the oil fields around Taft had swarmed with motion. At the time that he took over the rec center, Kern County drilled over 140 million barrels every year, more oil than almost any other county in the U.S. That oil flowed out of the ground and through a network of pipelines to nearby refineries for conversion into diesel. Above the pipelines, workers in hard hats and jumpsuits circled the fields in pickup trucks to monitor production; others manned towering drill rigs that rattled as they bored into the ground.

All this motion made money, and the companies that ran the oil fields shared some of that money with Taft, showering the town with millions of dollars in tax revenue and making philanthropic donations to fund schools, scholarships, and community events. While Taft is home to just 1 percent of Kern County’s population, the town’s plight is emblematic of that facing the entire county, a sprawling metropolitan area of nearly a million people whose middle class and tax base are firmly anchored by oil.

As the heart of Kern County’s oil industry, Taft enjoyed a prosperity that neighboring areas did not; the town sits at the southern end of California’s Central Valley, an agricultural region that struggles by almost every metric of health and social welfare. Many Central Valley towns don’t have grocery stores or parks, let alone an athletic complex like the one run by Clark.

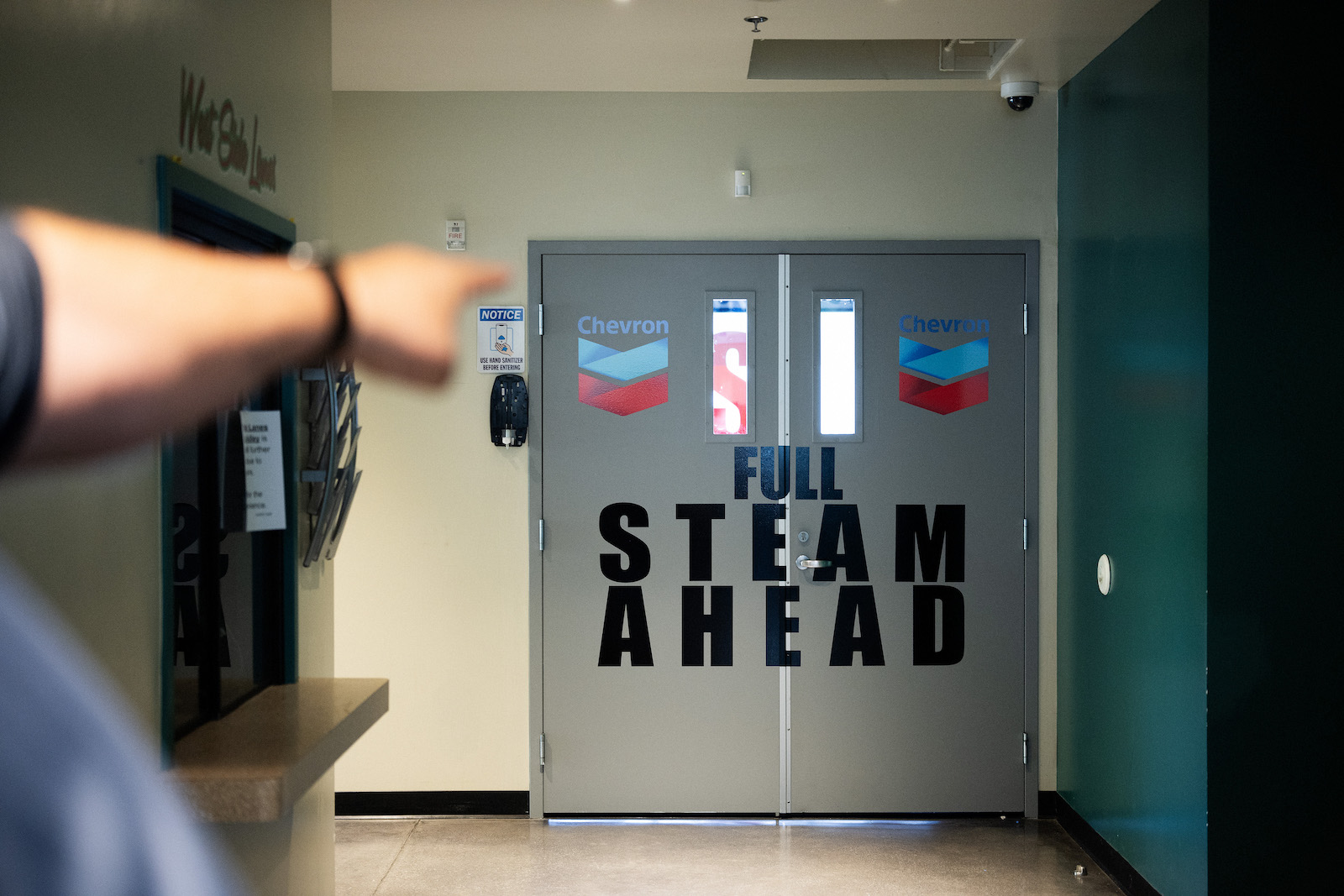

Indeed, Clark’s recreation center campus, which stretches across four buildings, encapsulates the town’s unique prosperity. It boasts a virtual empire of sports and leisure activities — not just the usual youth football and softball but also bingo, jazz dance, bunco, jiujitsu, and bowling, plus a weekly potluck dinner. More than half its budget comes from oil industry contributions, and individual companies have endowed some of the biggest expansions: the Aera Energy gymnasium, the Berry Petroleum movie theater, the Chevron science room for kids. Clark, who just turned 49, proudly dons a black ball cap adorned with the park district’s logo, an oil rig rising up from green fields on a sunny day.

But starting about a decade ago, Taft began to lose its grip on middle-class prosperity. The world oil market took a nosedive in 2014, leading local companies to lay off workers and idle wells in the fields around Taft. Even after oil prices bounced back, a new wave of environmental lawsuits and an oil permitting pause instituted by Governor Gavin Newsom stopped local oil companies from drilling new wells. Meanwhile, the rise of fracking diverted industry investment to untapped shale deposits in states like North Dakota and Texas.

As drilling slowed in Kern County, oil company contributions to the parks district disappeared as well, forcing Clark to lay off 10 of his 14 employees and scale back sports when he couldn’t find volunteers. Then the families of laid-off oil workers started telling him they couldn’t afford to enroll in youth sports — except for the baseball and softball leagues, where Chevron continued to cover all the costs.

Clark’s father and grandfather both worked in the oil fields, but he had never wanted to follow them there. His passion was for sports, and when pro football didn’t work out he figured that coaching at the town’s rec center was the next best thing. But the oil crash hit him just as hard as it hit his neighbors who worked for Chevron; when the industry sank, it took the rec center and the rest of the town with it. Clark is a large man, with a voice that travels even without the aid of the basketball gym’s acoustics, but his speech gets clipped when he talks about the impact of the oil crash on the kids who played on his softball teams, and the adults who took his fitness classes.

“It’s a tough deal,” he said. “We’re at a point where we can’t afford to spend in the red anymore.”

In recent years, as governments around the world have begun to shift away from fossil fuels and commit to stemming climate change, scholars and activists have promoted the idea of a “just transition” for communities that rely on carbon-intensive industries. The promise of a just transition is that the government will step in to support displaced workers and abandoned communities, offering subsidies and direct financial support to help build new industries and stave off economic collapse.

So far, this has not happened. The collapse of coal in Appalachia has helped slow climate change by reducing greenhouse gas emissions, but it has also eliminated tens of thousands of jobs and emptied out towns across Kentucky and West Virginia. Efforts to stoke new growth with corporate tax breaks, relocation stipends, and broadband investment have so far borne little fruit — though a recent wave of industrial policy legislation from Congress hopes to change that. The growth of renewable energy and the rise of electric vehicles now threaten to condemn oil communities to the same fate. Multiple large California refineries have closed in recent years, pushing hundreds of workers into lower-paying jobs or long-term unemployment.

Kern County hopes to take a very different path, transforming its fossil fuel industry into an industry that will help reduce carbon emissions. In 2021, the oil company California Resources Corporation, or CRC, unveiled a first-of-its-kind plan to capture millions of tons of carbon dioxide and stash it in depleted wells near town, preventing the greenhouse gases from wreaking havoc on the atmosphere.

Both CRC and Kern County officials promise that the project will deliver thousands of new manufacturing jobs, many of them perfect for former oil workers. They also say it will refill local tax coffers and restore institutions like Clark’s rec center. In theory, a carbon storage boom would help Kern County leap over the abyss created by the decline of oil, allowing the county to fashion its own “just transition” without a government bailout. To Clark, it all sounds like a godsend.

The plan’s ambitious promise has created a curious spectacle: an oil town rallying around a pivot to climate action by the state’s largest oil company. Leaders from the high school, the community college, and its chamber of commerce have all joined Clark in endorsing the project. It even landed an endorsement from Taft’s mayor, an ardent critic of renewable energy.

“There’s some kind of window of opportunity, because the industry is trying to evolve,” said Clark.

The consensus view of the “just transition” is that governments will have to make big investments in places like Taft to fill the void left by fossil fuel companies. Kern County is attempting something altogether different by trying to build a new boom industry out of the ashes of an old one, allowing oil companies like CRC to pass the torch to themselves as the county’s economic leaders. If the scheme pans out, the carbon management industry will act as a pacemaker for an ailing economy, replacing a carbon-spewing business with a carbon-saving one, all while protecting the fragile middle class created by oil.

The audacious initiative is not without its critics. Many residents of the Latino communities near Elk Hills, the massive oil field where the carbon will be stored, are concerned about the safety of stashing such huge volumes of the greenhouse gas underground a few miles from their homes. Some California climate activists are skeptical that the potential benefits of carbon capture are worth extending a lifeline to the oil fields near Taft, and they question if an effort designed to revive the oil industry can help the Kern County communities that never benefited from it in the first place. (Taft is about 60 percent white, but Kern County overall is about 60 percent Hispanic.)

From Clark’s vantage point at the rec center, there isn’t much of an alternative. As he sees it, Taft’s relationship with companies like CRC is the reason his hometown has so much more to offer residents than the towns around it. In fact, CRC representatives reached out to Clark directly to talk about how the company’s carbon capture plan could benefit the parks district. Next week, the rec center will unveil a new sports complex with a soccer field, volleyball court, and bonfire area — all thanks to CRC. If carbon capture can renew Taft’s prosperity, Clark is all for it.

“They made a point to come to us, because they know we’re hurting,” said Clark. “They wanted to make sure that we’re OK.”

Most booms begin with the sudden discovery of a new resource: Think of the gold strike at Sutter’s Mill that drew hundreds of thousands of people to California’s mountain mines, or the Spindletop oil gusher in Texas that gave birth to an American petroleum boom almost overnight. The carbon boom in Kern County, if it comes to pass, will be very different. It will have been reverse engineered, built not around a new resource but around the loss of an existing one.

Oil production in Kern County has been falling for decades, but the industry’s rapid decline over the last 10 years has thrust the county of almost a million people into a crisis. In 2014, when crude prices started to slump, oil and gas facilities accounted for almost a third of all assessed property tax value in the county. Within two years, the value of the county’s wells had fallen by half, dealing a $61 million hit to the county’s budget and wiping out more than 4,000 of the county’s approximately 12,400 oil jobs. Those jobs were some of the highest-paying in the area, with many salaries more than triple the average county salary of around $50,000.

The crisis fell into the hands of Lorelei Oviatt, the county’s director of planning and natural resources, a powerful and divisive public official with an astonishingly intricate grasp of economics and environmental law. When Oviatt attended college in Ohio in the 1970s, she watched the Rust Belt economies around her collapse as manufacturing jobs fled overseas. She was determined not to let the same thing happen in Kern County, where she took over the planning department in 2010.

Oviatt’s strategy for economic revival could be summarized as “all of the above.” While she has tried to speed up permits for new oil drilling, she also hedged her bets by simultaneously permitting several large solar and wind farms in the county. In doing so, she helped make Kern County a national leader in renewable energy and filled the landscape around her home in the county’s eastern mountains with thousands of rotating wind turbines. But neither solar farms, which require very little labor after construction and are exempt from local property taxes in California, nor wind, whose footprint is limited by the county’s geography and transmission constraints, could match the economic windfall of oil.

“It’s death by a thousand cuts,” said Oviatt. “The state of California’s energy policies are pushing us at an accelerated rate, because climate change is an urgent issue, but they are not providing us any assurances that we can keep our libraries open, or that we can keep Meals on Wheels. So we’re kind of under the perspective here that Kern County needs to design our own future.”

Brian L. Frank / Grist

Lorelei Oviatt, Kern County’s director of planning and natural resources, has promoted both oil and renewable energy in the county. Brian L. Frank / Grist

Wind and solar have been greatly expanded in recent years in Kern County. Local officials and oil companies have touted the benefits of combining green technology with carbon capture to offset the carbon footprint of the petroleum industry and provide needed energy to California.

Brian L. Frank / Grist

Oviatt has permitted almost 20,000 megawatts of solar and wind energy in Kern County, making the county one of the nation’s leading producers of renewable power. Brian L. Frank / Grist

Brian L. Frank / Grist

The oil companies themselves approached Oviatt in 2021 with a potential solution. If Newsom and the courts wouldn’t let them drill more in Kern’s oil fields, maybe they could use those same fields to store carbon dioxide. Studies suggested that depleted oil wells and the underground formations that stretch out beneath them were an ideal place to store captured gas: The wells stretched more than a mile into the earth, they sat in remote fields that were miles away from any residential area, and the companies already had the expertise to move gas around underground. California was betting on carbon sequestration to help it achieve its climate goals, and a provision in the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act nearly doubled the tax credits available to companies capturing carbon. Even conservative estimates suggest that the Central Valley could store at least 17 billion metric tons of carbon in perpetuity, which theoretically is far more than enough to get California to net-zero emissions.

There are two types of carbon capture: “point-source” capture, which involves sucking up carbon-filled air directly from pipes and smokestacks before they release it into the atmosphere, and “direct air capture,” a newer process that uses high-energy fans to extract carbon dioxide from ambient air. Kern County’s oil industry has thrown its weight behind both. CRC, Chevron, and Aera have all announced plans to pursue point-source capture at pipelines and power plants on their existing oil fields, and they also all won federal grants to build direct air capture facilities near Taft.

No company was more devoted to this idea than California Resources Corporation. After exiting a debt-driven bankruptcy in 2020, the company began an aggressive pivot toward carbon capture, planning a slew of carbon storage projects in the Central Valley and pitching itself as a “different kind of energy company” to new investors. CRC later bought Aera in a transaction that the company said would double its “premium CO2 pore space.”

“In our efforts to mitigate climate change, we are … laser-focused on investing in and growing our carbon management business,” said Francisco Leon, the company’s CEO, in an open letter to investors last year.

It was easy to see the business case: CRC’s inaugural project at Elk Hills, which it calls “Carbon TerraVault I,” will capture gas from the oil field’s infrastructure and its onsite power plant, reducing the carbon emissions tied to the company’s traditional oil production and streamlining its compliance with California climate regulators.

Even more important, though, is the revenue CRC hopes to generate by selling space in its carbon wells. If other factories or companies want to reduce their emissions, they can pay CRC to bury captured gas underground. The company has already signed deals to store carbon for a hydrogen plant, a dimethyl ether plant, and a “renewable gasoline” plant, all in the works near Elk Hills. All told, Carbon TerraVault could store more than 46 million metric tons of the greenhouse gas, enough to theoretically negate the annual emissions of a million passenger cars.

Oviatt saw something even bigger in CRC’s strategy, something that she thought could reverse the county’s economic tailspin. She drafted a proposal for what she called a “carbon management business park,” an interlinked complex of new factories that would produce hydrogen or steel — and store the carbon they emitted doing so in nearby oil fields. CRC, Chevron, and Aera had all expressed their interest in such projects, and Oviatt wanted them to know the county was open for business. She also invented what she termed a “cumulative impact oil and gas reservoir pore space charge” — basically a county tax on the space used for carbon capture.

When the county commissioned a third-party study to estimate the economic benefits of all this new industry, the results told Oviatt all she needed to know: A full-size carbon park would generate up to $56 million in tax revenue, about three-quarters of what the oil industry contributed in 2019. Even more importantly, it promised to provide a destination for former oil workers. The report was light on precise details, but it claimed that “at full buildout, the [business park] and related off-site activities would directly and indirectly support 13,500 to 22,000 permanent jobs.”

Despite the rosy projections, the scope of the challenge was not lost on Oviatt. CRC and the county were proposing to engineer the kind of industrial boom that typically happens by accident, and to do so in the span of a single decade. Success would require buy-in from almost every civic pillar of the county — not just its elected officials, industry advocacy groups, and three chambers of commerce, but also the institutions that support its residents from cradle to grave.

Kern County’s colleges and workforce development programs have already begun to pivot. After California Resources Corporation donated $2 million to the Kern Community College District in 2022, the district established the “CRC Carbon Management Institute” to create “customized workforce development opportunities” in the new industry. Bakersfield College debuted a new course on the subject, “ENER B52NC, Carbon Capture and Storage,” which included “discussion about the upcoming career opportunities in this field.” Even high schools are buying in; a handful of area teachers have been trained to teach carbon capture by experts from the world-famous Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in Berkeley. At a recent high school career day in Taft, CRC passed out handheld signs that allowed students to announce they were “future leaders in carbon management.”

Labor unions also endorsed the plan. Most oil field jobs in the county are nonunion, but construction trade unions like the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers could benefit from hundreds of temporary construction jobs that such a buildout would create. Plus, the business park promises to bring thousands of new manufacturing jobs to a county that has historically had very few, given that any new factory would theoretically have instant access to a system that could neutralize its carbon emissions. It helped that CRC already had a cozy relationship with the trade unions; the company agreed in 2016 to hire union contractors for all its maintenance work, and the unions are now negotiating a new agreement with CRC that would cover the company’s carbon projects.

It’s easy to understand the reasoning behind these endorsements: Carbon capture promises to solve one of the most vexing problems of the just transition, the question of how to replace a high-paying and labor-intensive industry. A high school graduate in Kern County can make six figures working for Chevron or CRC without attending a day of college, and thousands of families in the area have attained middle-class prosperity thanks to oil field work. Many workers who’ve lost jobs with these companies have left Taft for states like Texas and North Dakota rather than transition to a new industry. They have taken their sales taxes and property taxes with them, exacerbating the area’s economic pain.

Still, Kern County is better off than many other coal- and oil-producing regions, because it is still growing: The county has recently secured new investments in hydrogen, biodiesel, and warehousing, and its solar and wind farms have created hundreds of temporary construction jobs. The county has done its best to help laid-off oil workers transition into these new fields. Its workforce development department holds “rapid response” orientations at oil fields where companies are about to announce layoffs and pays for laid-off workers to take construction or electrician training courses. Kern Community College District also runs a “21st Century Energy Center” that designs certificate programs for energy workers, allowing them to train in electric vehicle charger maintenance and solar panel installation.

But none of these industries has reached anything like the scale of the oil industry, and many of them are either too temporary or too low-paying to be more attractive than oil field work, which requires far more operational and safety expertise than working in an Amazon warehouse or building a solar panel — and thus tends to pay much better. Until a few years ago, the Kern Community College District’s renewable energy center still offered a rudimentary oil safety training called the “oil field passport.”

“To be honest, if our people get jobs out working in the oil field, that’s not a negative, because the ultimate measure is that they got a family-sustaining job,” said Dave Teasdale, the director of the 21st Century Energy Center. “But we do have the concern about, how much longer are they going to be working there?”

The manufacturing complex at Oviatt’s new carbon business park promises to marry the best of both worlds: the labor intensity and remuneration of oil field work with the sustainability and growth potential of renewable energy. Plus, the skills needed to put carbon dioxide into an oil well are not that different from those required to take oil out of it, so many oil workers could transition to the new work with minimal retraining.

But the avalanche of jobs is hardly guaranteed. The state permit for CRC’s first cluster of carbon wells says that they will create 80 temporary construction jobs but only five permanent positions. The county won’t see the full benefit of carbon capture unless steel manufacturers and hydrogen startups flock to the county for CRC’s carbon storage space, and that depends on factors that are outside the county’s control. If companies find other ways to cut their emissions — or if the EPA halts the process of carbon storage out of safety concerns — the market for the carbon business park might vanish.

That hasn’t stopped most of the county’s civic leaders from pinning their hopes on the project. Earlier this year, when the EPA hosted a public hearing to discuss the carbon storage project’s potential impact on underground aquifers, representatives from almost every major county institution attended to praise carbon capture as an economic boon. The EPA had already given provisional approval to CRC’s carbon storage effort, but everyone from union leaders to community college administrators showed up to stress their support for it.

The hearing was held in the farmworker community of Buttonwillow, which is almost 90 percent Hispanic, and a number of residents and environmental justice advocates showed up to voice their fears that the stored carbon dioxide would leak into the surrounding air. This has happened at least once before when a pipeline in Mississippi ruptured and hospitalized 49 people, but the EPA views such a calamity as unlikely in Kern.

Meanwhile, the boosters kept beating the drum of economic development. One oil company owner declared that the project would help “hundreds or thousands of young men and women to launch their careers,” while another former oil worker who taught at Taft High School said the project would help “those people who are being transitioned out of the petroleum industry” to keep working in the county. Les Clark and his rec center employees were there, too, and Clark took a turn at the microphone to celebrate the economic revival CRC promised to bring to Taft.

The EPA officials at the hearing only had the legal authority to consider the project’s effects on water quality, and many of them were only present because of their geological expertise. As dozens of locals stood up one by one to thank CRC for saving Kern from economic ruin, the regulators could only smile and nod.

Danny Gracia, 45, grew up in Buttonwillow, near the Elk Hills oil field and about 20 miles from Taft. At that time Buttonwillow was a hub for the American cotton industry, and the work was grueling. Gracia’s mother and father worked long shifts at the town’s massive cotton gin to provide for him and his three older brothers. As soon as Danny’s brothers reached adolescence they joined their parents at the gin to help support the family, making only $8 an hour each.

This was the status quo for tens of thousands of people in Kern County in the 1990s — and it still is today — but Gracia managed to escape it. He was still in high school when one of his brothers heard about a job opportunity on a drilling rig; soon he was making far more money than the rest of his family. When Gracia graduated high school, he joined his brother in the field for a summer job, then quickly took a permanent position expanding old wells. His company paid for him to rack up trainings and certificates, and within a few years he got a promotion to rig supervisor, which allowed him to buy a house at the age of 21. His mother was able to quit working at the gin and stay at home cooking for Danny and his brothers, who paid her for feeding them between shifts.

“My intention coming into the oil fields was to provide a good life for my families like my brothers and friends,” he told me. “I did more than that. I made a career out of it. I gave my family more than I ever thought possible.”

Gracia’s story shows why so many of Kern’s institutions have rallied around carbon capture as a successor to the oil industry. But it also shows why many environmental and economic justice organizations are critical of the county’s plans: Carbon capture might help oil workers like Gracia, but it doesn’t do much for other people in towns like Buttonwillow who have never benefited from the oil industry — and who may have suffered harmful health effects from living near oil infrastructure. Agriculture employs around 30,000 people in Kern County, more than twice as many as the oil industry, but most of those workers make around $20,000 a year, and there are nowhere enough training programs or job openings in the oil industry for these workers to ascend the economic ladder. As some activists see it, the county is missing out on the opportunity for broader economic reform with its focus on mitigating the decline of oil.

“We talk a lot about oil workers, and I respect that, but at the same time, there are a lot of agricultural workers that are sustaining a lot of the economic health of the region,” said Daniel Rodela, a community organizer who grew up in an agricultural community near Taft and now works at a nonprofit called Faith in the Valley. “But obviously, in our community, there’s going to be folks that are going to be advocating for things remaining the way that they are.”

The Biden administration has sought to alter this dynamic as it plows money into clean energy projects in fossil fuel communities. The federal grant that CRC received for its direct air capture facility requires the company to create a “community benefits agreement” for its carbon projects, including commitments to disadvantaged areas around Taft. As it applied for permits to store carbon underground, the company also had to build social consensus across the county, including in agricultural communities like Buttonwillow.

CRC did not shrink from this task. As the company pushed Carbon TerraVault, it erected billboards near highways and oil fields in Bakersfield, announcing that the company was “committed to our net-zero future.” It held dozens of meetings with city leaders, environmental organizations, unions, and the family members of the activist Cesar Chavez, who co-founded the National Farm Workers Association in Kern County in 1962. CRC employees knocked on doors in Buttonwillow and the other communities around Elk Hills, taking selfies to document the effort, and sent out mailers in English and Spanish. They held a meeting at a movie theater in Taft that Clark’s rec center runs, playing a teaser video for carbon capture before screening the action movie Expendables 4. The company even dreamed up a partnership with Grandma Whoople Enterprises, an “anti-bullying entertainer” in nearby Bakersfield who agreed to conduct “elementary field trips for frontline community children.”

But these efforts don’t seem to have succeeded in building popular support for carbon capture, despite the wave of institutional endorsements for Carbon TerraVault. When the social justice nonprofit Dolores Huerta Foundation partnered with the University of California, Merced, to survey hundreds of disadvantaged Kern residents last year, asking them where they wanted to see more jobs, the top answers included solar, wind, and oil well abandonment. Carbon capture placed a distant seventh, with only 1 in 3 respondents endorsing it.

California Resources Corporation declined interview and comment requests for this story. A spokesperson for the company said it was in a “media quiet period” as it sought carbon capture permits. A representative for Chevron did not respond to questions about the company’s projects in Kern County.

There are alternative visions for Kern County’s revival, ones that don’t involve a project sponsored by oil. Many environmental organizations have given particular attention to proposals that would employ workers to seal defunct oil wells and clean up the land and water around abandoned oil fields. A report published by the Sierra Club last year found that there are more than 40,000 idle or orphaned wells in the state, and CRC and Chevron own more than two-thirds of them. Plugging all these wells could create at least 13,000 jobs in Kern County alone, the report found — almost as many as the carbon business park, though the former would by nature be short-term. Hundreds of millions of dollars in subsidies from the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law could help kickstart the effort. These jobs wouldn’t last forever, but they could allow much of Kern’s aging oil workforce to reach retirement without retraining. Temporary solar construction jobs could help fill the gap.

This remediation industry is at the center of a recent economic development proposal by the Center on Race, Poverty, and the Environment, or CRPE, a decades-old environmental justice organization based in Kern County. Drawing a contrast with the county government’s embrace of carbon capture, the proposal lays out a vision for a new workforce that would seal old wells, remediate oil land, and build public infrastructure, supplemented by a state program that would replace the wages of laid-off workers as they seek new employment. It’s a vision where government rather than industrial initiative is the driving force.

Juan Flores, a lead organizer at CRPE and one of the authors of this plan, said that many people in disadvantaged parts of the county are wary of the oil industry because they’ve suffered the health impacts of oil production, like cancer and preterm births.

“I think on that rubric of [a] ‘just transition,’ the county has failed,” he said. “They continue to think, ‘how can we keep the oil industry alive?’”

Others argue that carbon storage in Kern County could function as a public good rather than a private business. The Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory is proposing a “community-centered direct air capture hub” that would run like a public utility. Whereas CRC’s carbon complex could pitch in a share of its revenue to the county through property taxes, the Berkeley proposal could see locals elect a governing board that would manage the carbon facility directly and route its revenue toward impoverished areas.

These alternatives might not be that much more ambitious than Oviatt’s carbon business park, but realizing them would require a herculean amount of coordination between local governments, employers, schools, labor unions, and advocacy groups.

Kern County has shown that this coordination is possible, but only in service of certain ends. As the region’s largest taxpayers and most sought-after employers, oil companies have had an outsize influence over how the county navigates the energy transition. These companies have plowed millions of dollars into education and capital projects in the region even as oil itself declines, a stark contrast with the fate of Appalachian communities that saw their biggest employers cut and run during the collapse of coal. But the condition of this investment is that the county has to pursue economic development on the industry’s terms, and its transition to a low-carbon future will happen in a manner that benefits the industry rather than dismantling it.

The risks of this dynamic became apparent in the weeks after the carbon capture hearing, when a state appellate court dealt Kern County’s oil industry another defeat. A panel of judges voted to throw out Oviatt’s attempt to permit thousands of new oil wells, ordering the county to draw up a third environmental review for the drilling plan. This effort could take the county as long as a year to complete, and even then it would be subject to new legal challenges. But Oviatt was undeterred, and she got right back to work revising the permits.

“There’s no oil drilling, there’s no more money — those companies can roll up and leave and decimate our community,” she said. “These companies have to have money in order to evolve.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Inside a California oil town’s divisive plan to survive the energy transition on May 15, 2024.