On the very first day of COP28, the United Nations climate conference underway in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, nearly 200 countries adopted an unprecedented agreement: They set up an international fund to aid developing countries addressing the loss and damage caused by climate change. Within a few minutes of the announcement, the so-called loss-and-damage fund had received pledges of $100 million each from the governments of the United Arab Emirates, or UAE, and Germany.

“We have delivered history today — the first time a decision has been adopted on day one of any COP,” said Sultan Al-Jaber, the COP28 president overseeing the conference as well as the head of the UAE’s national oil company. “The COP28 presidency is committed to delivering outcomes for the climate-vulnerable.”

Get caught up on COP28

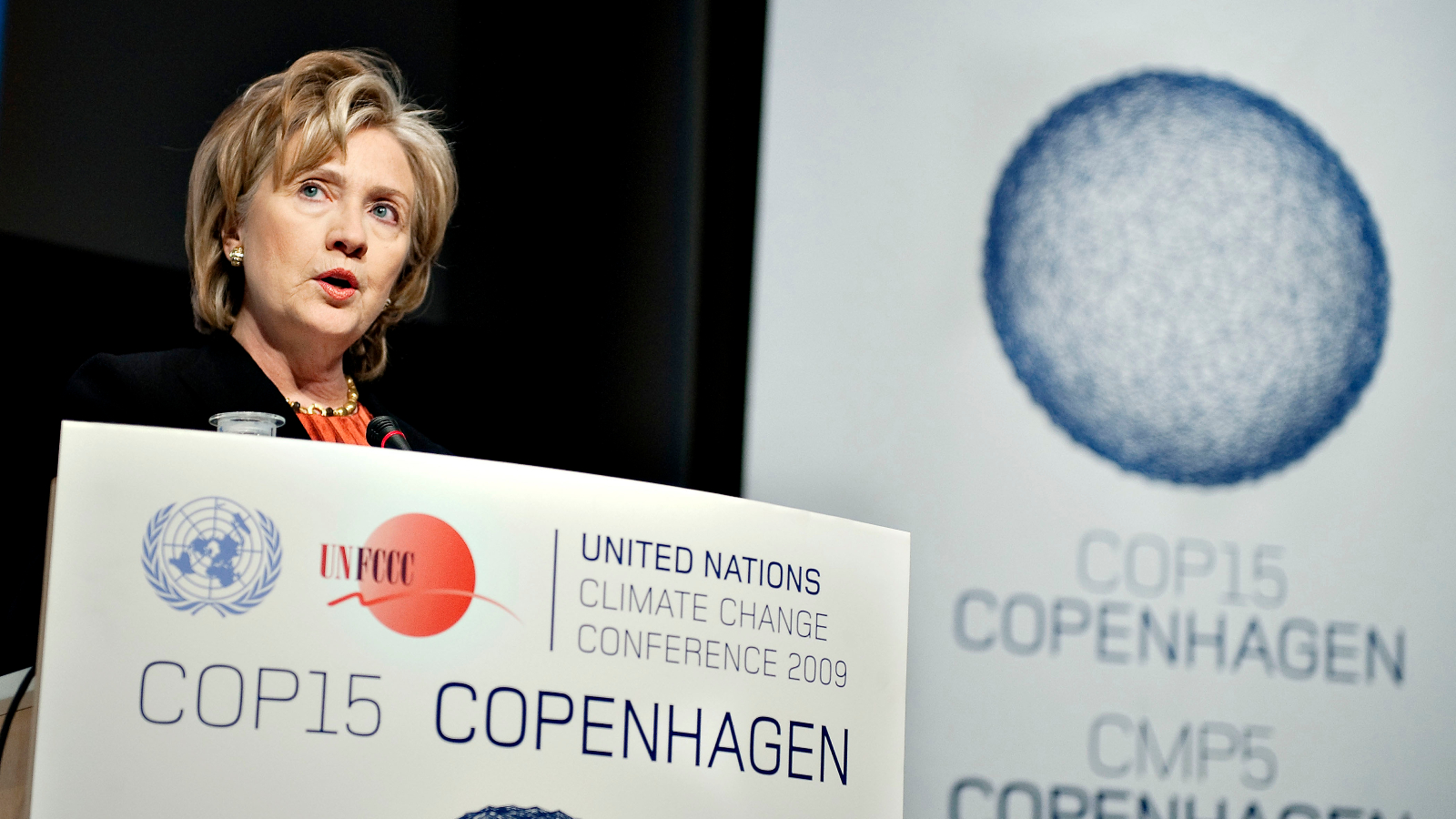

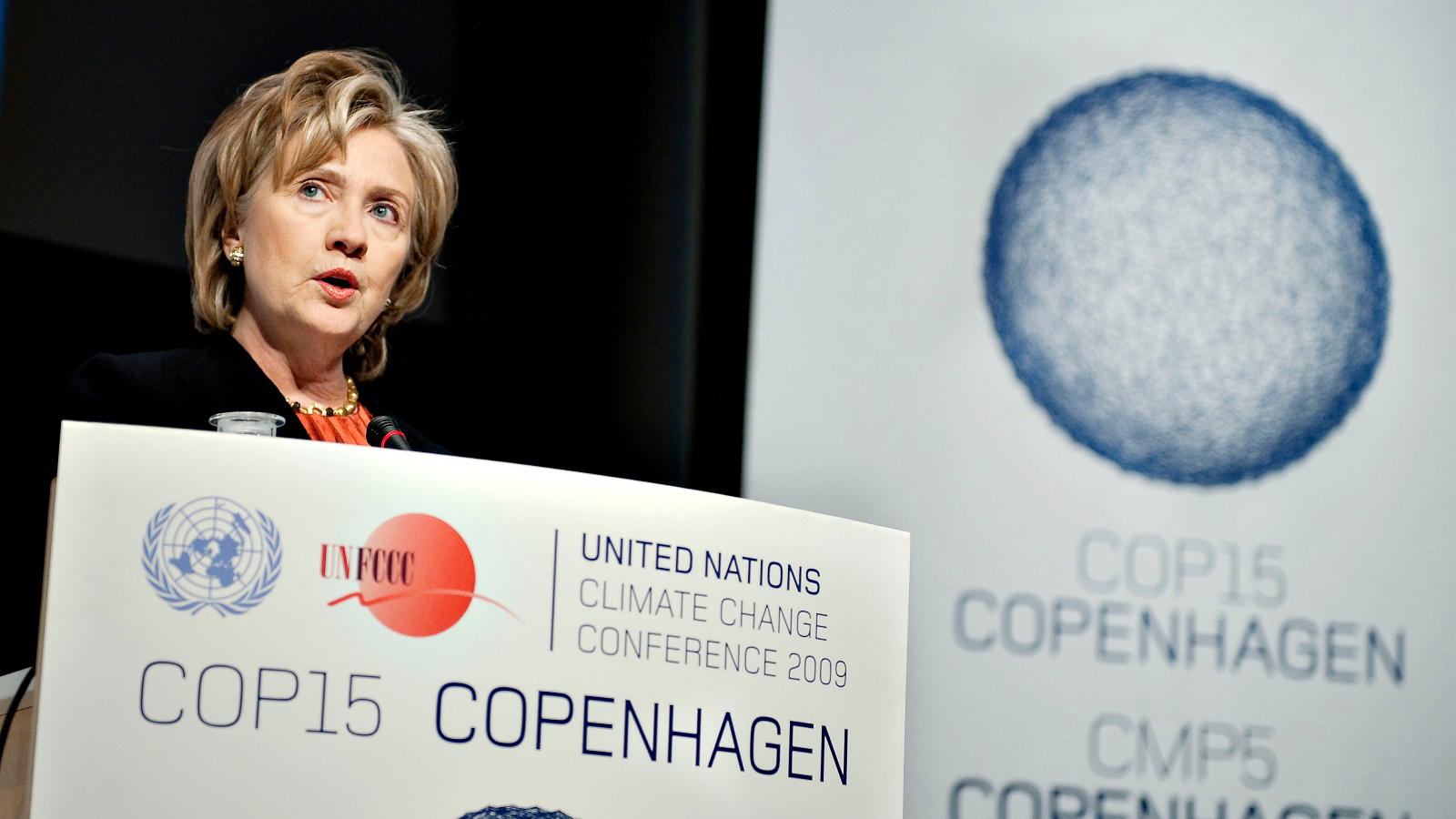

Germany’s large pledge to the fund was unsurprising, given its wealth and historical responsibility for the climate crisis as an early industrializing nation. Under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, or UNFCCC, wealthier and larger polluters have a duty to support still-industrializing countries bearing the brunt of climate change. This principle — called “common but differentiated responsibilities” — has often been a major point of contention in U.N. climate negotiations, with lower-income countries charging that wealthy nations are not providing their fair share of finance.

The UAE’s contribution to the loss-and-damage fund, however, could mark a dramatic shift in how this principle is understood going forward, according to COP observers who spoke to Grist. That’s because the UAE is a newly wealthy country, and one whose emissions only began rising substantially in the 1990s. Under the United Nations classification, it is still a developing country.

“The UAE pledge is significant,” said Joe Thwaites, a climate finance expert at the nonprofit National Resources Defense Council. “You’re starting to see countries say, ‘You know what? We are taking on the responsibilities of a developed country.’” Alex Scott, who leads climate diplomacy for the climate think tank E3G, echoed those comments. The UAE providing money goes to “the heart of the loss-and-damage fund agreement,” which states that “all countries that have the means to do so are invited to contribute to the fund,” she said.

The timing of the joint pledges from Germany and the UAE — one developed and one developing country — was deliberate. At a press conference a week later, German economic and development state secretary Jochen Flasbarth told reporters that “it was important for us, together with the UAE, that we make a visible statement by having a nontraditional donor, so that the old world of the industrialized nations and the then-developing countries are no longer in the same position.” This “old world” is one in which developed countries are expected to contribute, and all developing countries as defined by the United Nations are solely fund recipients. “We won’t fall back into this old world,” he said.

This bifurcated categorization of countries in the context of climate negotiations originated in 1992, when the UNFCCC treaty was adopted. The framework demarcated countries into two main categories: Annex I and non-Annex I. The former included wealthy industrialized nations such as the United States, Australia, and countries in the European Union, while the latter included countries that fell into the low- and middle-income designations at the time. But the rigid classification provided no room to recognize countries’ economic growth over the next three decades. As South Korea, Singapore, Qatar, and others have prospered, both their emissions and their ability to help poorer countries have risen in tandem.

As a result, industrialized nations like the United States and those in the European Union have urged newly wealthy countries to provide funding to climate-vulnerable countries — even though the U.S. and EU are still responsible for the lion’s share of historical emissions. Such calls have generated tension, with some developing countries interpreting the ask as a way for wealthy nations to abdicate their financial responsibilities to the rest of the world and pit developing countries against each other. Looming over these discussions is the fact that wealthy nations blew past a 2020 deadline to provide $100 billion in climate finance to developing countries. The broken promise eroded trust between developed and developing countries.

Nevertheless, the UAE’s pledge has been welcomed by at least some other developing countries.

“It’s a good thing,” said Senegalese negotiator Idy Niang, who advocates on behalf of a bloc of the least-developed nations. “Those who can [contribute] should.”

The 2015 Paris Agreement belatedly recognized that countries might graduate from non-Annex I to Annex I. The agreement references “developed country parties” and “developing country parties,” but it doesn’t define which countries belong in each category. “It’s never explicitly spelled out anywhere,” said Thwaites.

Though its contribution was in some ways the most significant, the UAE isn’t the first developing country to contribute to a United Nations climate fund. At least 10 other countries, including South Korea, Mongolia, Mexico, Colombia, Peru, and Qatar, have contributed to the Green Climate Fund and the Adaptation Fund, which were set up to provide support to developing countries. Most of these contributions amounted to a few million dollars apiece. South Korea, however, which has one of the largest economies in the world, provided $100 million in 2014 and followed up with $200 million in 2019 and $300 million earlier this year.

“South Korea doesn’t get enough credit for that, because they’ve been quietly increasing over the years,” said Thwaites. “They do it without fanfare, and they do it without making a big deal about it.”

It’s unclear if South Korea will pledge to the loss-and-damage fund. A South Korean negotiator told Grist that he hadn’t heard from senior officials in the government about how much the country would pledge.

Niang, the Senegalese negotiator, said that while contributions from wealthy developing countries are welcome, the responsibility to provide funding as underscored in the UNFCCC still lies with the developed countries who have emitted the most carbon over their histories. “We need to reaffirm in the decision text that the historical responsibility and the common but differentiated responsibility is there,” he said. “We need to go back to the convention. The convention does not recognize that Korea or UAE are responsible.”

Still, the UAE pledge has become the most prominent example of a wealthy developing nation providing climate aid. It’s also the first Gulf state to provide substantial funding; while Qatar pledged to the adaptation fund in 2021, its $500,000 contribution was largely symbolic. Thwaites said that the UAE pledge will put pressure on Saudi Arabia to step up.

“They have typically been the big holdouts here, but when their neighbor and peer and quite close ally is willing to step up with not just a small token amount but the joint second-biggest pledge to this new fund, that’s really significant,” said Thwaites. “The Saudis are going to be feeling the pressure.” (Saudi officials did not respond to Grist’s questions, and UAE officials declined to comment about the pledge.)

One big question is whether any pressure will be felt by China, which is by far the largest national emitter of carbon dioxide in the world at present. Wealthy countries have long been pressuring China to contribute to international climate aid. In the 1990s, when the United Nations classification was established, China was much, much poorer and its emissions were low. But its rapid economic growth, unprecedented in world history, took off around that time; as a result, its emissions surpassed those of the U.S. by the mid-2000s. The country has provided some climate aid outside of United Nations funds and also contributed nearly $130 million to the Green Environment Facility, which has a broader mandate than just tackling climate change. But it hasn’t met calls for more substantial funding, and last year Chinese climate envoy Xie Zhenhua said it wouldn’t contribute to the loss-and-damage fund.

“China does want to position itself as a supporter of Global South nations,” said Alex Wang, a law professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, where he studies Chinese environmental governance. “Right now there is a sort of geopolitical competition among the West and in China to win the favor of Global South countries.”

The commitments to the loss-and-damage fund over the last week came as a relief to many. Negotiators and climate advocates feared that they would spend precious time and energy at COP28 debating details of the fund’s operations and that wealthy countries wouldn’t pledge money. The World Bank, which is expected to host the fund for the first four years, had announced that it needed $200 million to just set up the fund. The Germany and UAE pledges alone ensured the fund would have the capital it needed to get started. So far, roughly $725 million in pledges — including those of the German and Emirati governments — have poured in.

“It was very important that loss-and-damage finance is not a bargaining chip,” Jennifer Morgan, Germany’s climate envoy, told Grist. “There is a saying in German: ‘A heavy stone has fallen from your heart.’ It describes well what negotiators said they felt. Many are relieved. Now there is more space to discuss other issues.”

Editor’s note: The Natural Resources Defense Council is an advertiser with Grist. Advertisers have no role in Grist’s editorial decisions.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How two $100 million pledges shook an ‘old world’ order at COP28 on Dec 11, 2023.