Tune in for an important conversation about the future of krill, the billions of tiny crustaceans that are…

The post Earth911 Special Video Event: How Saving Krill Could Help Save The Planet appeared first on Earth911.

Category Added in a WPeMatico Campaign

Tune in for an important conversation about the future of krill, the billions of tiny crustaceans that are…

The post Earth911 Special Video Event: How Saving Krill Could Help Save The Planet appeared first on Earth911.

This story was co-published with the Tampa Bay Times and produced in partnership with the Toni Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism and the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University.

Laurie Giordano stood before a committee of Florida lawmakers in 2020, her hands trembling. She was there to tell the story of her son Zachary Martin, a 16-year-old football player who had died from heat stroke three years earlier.

“No mom should ever drop their kid off at football practice and then never hear their voice again,” she said, pleading for the passage of a bill that would provide heat-illness protections for high school athletes in Florida.

“Exertional heat stroke is 100 percent preventable and survivable, if we are prepared,” Giordano told the lawmakers. If her son were alive today, she said, he would be fighting for the bill’s protections, like rest and water breaks, which could have saved his life.

The legislators heeded her call and passed the Zachary Martin Act in her son’s honor just two months later. Since then, no student athlete has died from heat stroke in Florida, which now ranks highest in the country for its school sports safety provisions.

Two years after Martin’s death in Fort Myers, a Haitian farmworker in his 40s named Clovis Excellent died from heat stroke at a farm just north in Bradenton. He had been working for five hours, pulling stakes from tomato beds in temperatures exceeding 90 degrees Fahrenheit.

The Occupational Health and Safety Administration, or OSHA, investigated his death and found that, given the intensity of the work, the temperatures he was exposed to were unsafe without regular breaks in the shade. But Utopia Farms II, like many farms in the state, did not require its workers to take breaks, no matter the heat.

At least seven other outdoor workers died from heat illness in Florida in the two years between Martin’s and Excellent’s deaths, according to federal fatality records. During that time, labor advocates pushed lawmakers to establish heat-illness protections for Florida’s 2 million outdoor workers. These measures included rest breaks, shade, and water, as well as heat-illness first-aid training.

But those efforts failed. More worker heat-safety bills have been filed in Florida than any other state, but none has made it past a single committee hearing.

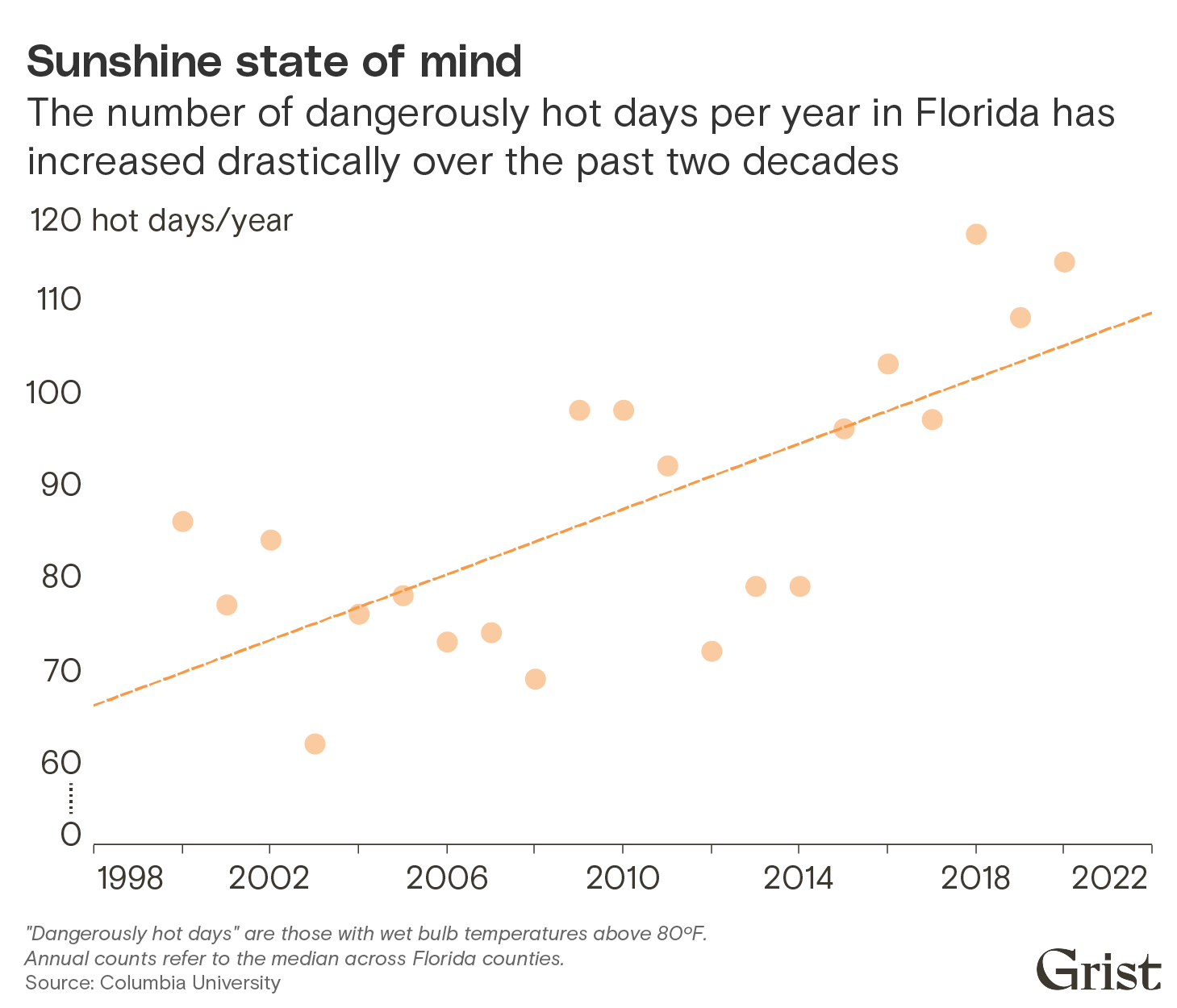

Florida is the hottest state in the country and has some of the highest rates of hospitalization due to heat illness, which kills more than 1,200 Americans a year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC. The number of workplace fatalities from heat has doubled since the 1990s, averaging over 40 workplace deaths a year for the last five years. While California, Colorado, Minnesota, Oregon, and Washington have all passed regulations to protect workers from heat illness, there is no national heat standard; OSHA, the federal agency that regulates workplace safety, is in the process of drafting one, but it could take around seven years and there are no guarantees that it will be enacted.

Heat is already the deadliest weather event, and as climate change causes temperature spikes to become more common and unpredictable, the threat will only increase, especially for those most vulnerable to heat illness. No one can predict how communities will adapt — what investments will be made to prepare for the heat waves of the future and how those protections will be distributed — but the disparities in whom lawmakers choose to protect are telling.

When Zachary Martin, a 16-year-old football player, died from heat stroke, there was widespread press coverage and the Florida legislature voted unanimously to mandate that schools have emergency medical plans to treat heat injuries.

When Clovis Excellent, a Haitian immigrant in his 40s, died from heat stroke, his name never appeared in the papers, and bills recommending similar protections were largely ignored by lawmakers.

On June 29, 2017, Laurie Giordano was checking her phone in her parked car near Riverdale High School when one of her son’s teammates tapped on the glass.

“Zach is down,” the boy said.

Her son Zachary, or “Big Zach,” as his friends called him, had been playing football since he was in eighth grade. The summer before his junior year, he stood 6 feet, 4 inches tall, weighed 320 pounds, and wore a size 15 wide shoe. He wanted to play football in college, maybe even professionally. He worked hard in his classes and pushed himself during preseason practice, determined to be a starting player on the varsity team the next year.

When she got to the field, she saw Zachary seated on the ground. Two teammates were holding his arms and an assistant coach was propping him up from behind. Coach James Delgado told Grist that they were trying to keep him upright to prevent him from choking. The boy had collapsed after completing about three hours of indoor training and running drills outside in the 90-degree heat. His coaches and teammates had assumed Zachary was dehydrated, so they offered him water, but he immediately vomited after drinking it. Soon, his condition worsened.

Zachary was moaning. His eyes were closed; his head, drooping. He hardly looked conscious.

Giordano was shocked. “Everything in me was saying this was not right,” she told Grist.

Delgado called 911. The fire department was the first to arrive on the scene, followed by the paramedics, who brought Giordano’s son to the hospital. The doctors determined that Zachary was suffering from heat stroke, a condition that can be fatal.

When a person reaches that stage of heat injury, the body loses its ability to cool itself, and internal temperatures can rise within a matter of minutes to 107, 108, 109 degrees. If the person is not rapidly cooled within the first 30 minutes, their organs can fail. Time is essential.

Zachary made it to the hospital over an hour after he collapsed. The doctors covered him in ice to try to lower his temperature. He was in a coma for more than a week.

Giordano slept in the hospital every night. She saw him wake up twice: The first time, he tried to pull himself from his bed, half-conscious. It took multiple nurses to restrain him.

“He was scared,” Giordano said. “He didn’t know where he was.”

The second time, all he could do was squeeze her hand.

Two days later, he died.

“He fought,” Giordano said. “He fought so hard.”

On the ride home from the hospital, Giordano remembers turning to her husband.

“We’re not going to take a loss on Zach,” she told him.

“At the time, I wasn’t even 100 percent sure what had happened.” Giordano told Grist. But she sensed that the school’s response had been inadequate. Days after her son’s death, she set out to discover whether it could have been prevented.

She got on her computer and looked up what heat training Riverdale High School coaches received. The National Federation of State High School Associations certifies coaches throughout the country, and it had provided the training materials for Riverdale’s athletic staff. It had an online course on heat illness, but it was optional. She found that in Florida, no agency ensured that high school coaches were trained in heat-illness prevention.

Watching the online training videos, Giordano found that all the major symptoms of heat stroke — collapsing, disorientation, slurred speech, vomiting — were the exact symptoms Zachary had experienced. She also learned that, if treated quickly, heat stroke fatalities are entirely preventable using a technique called “cold water immersion.” It sounded essentially like dunking someone in a tub of ice water.

“It can’t be that simple,” Giordano thought.

She looked at resources from the Korey Stringer Institute, a leading researcher in sports medicine that specializes in heat illness, and found that it was. Schools could use “cold tubs” — essentially plastic tubs filled with ice water — to save students’ lives.

“As soon as I heard the term ‘cold tub,’ I knew exactly what they were talking about. Because I had seen them,” Giordano said.

The week before her son’s collapse, Giordano had seen him outside the high school’s athletic facility loading ice into a large plastic tub filled with water. When she asked him what he was doing, Zachary had said he was helping some teammates who were cramping from the heat. They would sit in the tub after practice to relax their muscles and cool down.

But when Zachary passed out, the tubs were nowhere in sight. And rather than moving Zachary to a shaded area and trying to immediately cool him, which the online training said was critical for survival, his coaches left him on the sundrenched field until the paramedics arrived.

Giordano realized that the coaches at Riverdale had the tools they needed to save Zachary’s life. But when it mattered, they were not trained to use them.

She learned that the Florida High School Athletic Association, or FHSAA, was responsible for maintaining safety standards for the state’s high school sports teams. She met with its leadership to talk about the possibility of mandating heat-injury emergency plans.

The FHSAA had guidelines about heat-illness prevention but did not mandate training for coaches or the use of the cold water immersion tubs that would have saved Zachary’s life. The agency could investigate schools that were failing to uphold safety standards and penalize them if they failed to do so. But it did not proactively inspect schools, and its enforcement was largely based on self-reporting. The executive director of the organization, George Tomyn, told Giordano that the FHSAA lacked the authority and the capacity to mandate such policies for all of Florida’s schools.

According to Rebecca Stearns, chief operating officer at the Korey Stringer Institute, many student athletic associations like the FHSAA, which set the statewide standards for high school sports around the country, assume that they are not ultimately responsible for enforcing safety standards in schools.

“My question to them is always, ‘If not you, then who?’” Stearns said, noting that athletic associations have the medical expertise required to make informed decisions about student safety. Leaving it up to individual schools that lack these resources can lead to negative outcomes, she said.

The FHSAA did not respond to requests for comment.

Fort Myers’ local newspaper, the News-Press, wrote over a dozen articles about Zachary’s death and the dispute over the FHSAA’s policies. The story was picked up regionally by Fox 4 News and nationally by HBO’s Real Sports With Bryant Gumbel, which ran a 15-minute segment in which they confronted George Tomyn for not mandating the use of cold water tubs, despite training materials their organization provided that recommended their use.

The FHSAA debated the issue from 2017 to 2019. Their medical advisory board recommended that schools alter practice expectations based on the heat risk and keep cold water immersion tubs available. But the FHSAA decided not to act on the issue. They felt that the state legislature should be the one to enforce such a mandate.

Giordano attended these meetings for two years.

“It was heartbreaking,” she said.

Two months later, Giordano learned that another student athlete, a 14-year-old named Hezekiah Walters, had died from heat stroke during preseason football practice in the state.

While Giordano continued her fight for student athlete protections, a crew of laborers at Utopia Farms II were working in the fields outside of Bradenton, on Florida’s Gulf Coast. They moved along rows of barren tomato vines, yanking out stakes and preparing for next season’s planting.

A new employee, a man in his 40s who was working under the name Laurant Tersiuf, was struggling to keep up.

Tersiuf had started at Utopia only three days prior, and his crew leader, Juan Lozano, had noticed him repeatedly sitting down between the rows to catch his breath and complaining of stomach pain. Lozano was unsure whether Tersiuf had worked in tomato fields before and assumed he was simply unaccustomed to the grueling work.

During the harvest season, tomato workers are paid for every pound they pick, with a typical day’s pay around $80. Hunched over for hours, pickers hurriedly yank tomatoes from the vines and drop them into plastic bins. When the bins are full, weighing over 30 pounds each, the workers hoist them onto their shoulders and rush down the rows to hurl their bin onto a truck that gradually moves along a dirt path, setting the pace for the workers. One worker carries over a ton of tomatoes per day.

Farmworkers routinely avoid rest breaks because each minute spent resting is a minute of pay lost. Some even deliberately avoid drinking water so that they will not need to stop working to go to the toilet, which can be located hundreds of yards away, according to worker advocates.

By summertime, the tomato harvest is over, and workers are paid by the hour, not by the pace of their work, but it’s still one of the hardest seasons because of the heat. In temperatures that easily exceed 90 degrees, tomato workers clear and prep crop beds for the next growing season, often coming into contact with materials covered in pesticide residue. Some wear long sleeves, pants, gloves, and masks to protect themselves from the chemicals, but, according to a report by the nonprofit Union of Concerned Scientists, this can make workers feel hotter by up to 12 degrees.

Work-safety specialists say these conditions can be life-threatening without the ability to take rest breaks, drink water, and access shade. But in Florida — where workers spend over 100 days of the year in temperatures exceeding the limit the CDC recommends before safety measures are taken — it is up to the workplace to decide whether to provide these basic protections.

Lozano told Tersiuf he could take a day off if he was feeling sick, but he would lose that day’s pay. Tersiuf took some Pepto Bismol and returned to work. The wet bulb globe temperature, which accounts for factors like cloud exposure and humidity, climbed to 92.3 degrees, over 10 degrees higher than what OSHA deems high risk for workers performing strenuous labor. At 1 p.m. on June 27, 2019, after working for six hours, Tersiuf asked Lozano if he could sit in the shade next to a trailer and rest.

Around 3 p.m., according to investigators’ records, Tersiuf was found beside the trailer unconscious. The paramedics who arrived noted that his skin was dry and hot to the touch — a sign that his body had lost the ability to sweat. His temperature was 109 degrees.

Tersiuf was rushed to Lakewood Ranch Medical Center in Bradenton, but the doctors could not stabilize his temperature in time. His body was so hot that his cells began to break down, leading to organ failure.

Within two days, Laurant Tersiuf was dead.

When the hospital went through his belongings, they found identification indicating that Tersiuf’s real name was Clovis Excellent. Like many undocumented immigrants, he had probably gone by an alias to avoid immigration enforcement. And like many undocumented workers, his death was never reported by the local papers. Neither were the other heat-related deaths of farmworkers in the two years between Martin’s and Excellent’s deaths.

Administrators at Utopia Farms II notified OSHA about Excellent’s death, and the agency opened an investigation. OSHA has no mandated policies around heat exposure, despite demands for such provisions since the first years of its founding in the 1970s. They provide recommendations and educational materials about heat illness, but leave it up to businesses to decide what heat conditions are safe for their workers. And if a business chooses not to notify OSHA after a worker is seriously injured, as they are legally required to do, the agency may not even know about the incident. Injuries among undocumented migrant workers are easier to avoid reporting, because migrants often lack family and community members to advocate for them, are unaware of their rights, and fear retaliation. Researchers estimate that government reports on the number of occupational injuries among agricultural workers miss 79 percent of injuries and 74 percent of deaths.

In this sense, Excellent’s case is exceptional. Over several weeks following his death in 2019, federal investigators interviewed his co-workers and managers and inspected the fields where he worked. The investigators reprimanded the company for allowing their workers to perform such high-intensity work in extreme temperatures without shade or rest during the hottest period of the day. Utopia Farms II had provided fact sheets about the symptoms of heat illness to their workers in Spanish, English, and Creole, but investigators found that they had no plan to gradually introduce new hires — who make up 70 percent of reported worker-related heat fatalities, because their bodies are not acclimated — to the extreme temperatures. Clovis Excellent had been sent into the fields to work a full shift the same day he was hired and died five days into the job.

To redress Excellent’s death, OSHA requested in a citation letter that Utopia Farms II implement a new safety plan to prevent further heat injuries and send their agency a payment of $13,260. After Utopia challenged the fine, it was amended to $7,956. Because the agency has legal limits on the amount it can fine companies, the penalty was typical for serious violations of OSHA’s safety standards under its general duty clause.

The basic safety measures from heat illness Utopia had failed to provide are ignored by farms throughout the country, in part because OSHA has not mandated their use. They are merely recommended. If OSHA’s proposed heat standard passes, businesses will be required to change their act. But the agency will most likely struggle to enforce the rule because of perennial funding and staffing issues and their limited fines. In Florida, the agency has employed 59 inspectors to oversee the state’s approximately 10 million workers.

For years, farmworkers throughout Florida had been speaking to local labor organizers about the dangers of heat. Jeannie Economos, an advocate with the Farmworker Association of Florida, had heard countless stories of dizzy spells, muscle cramps, nausea, and dark, painful urination workers experienced after long shifts in the heat. Many told her they felt pressured by their employers to keep working no matter how sick they were and felt powerless to protect themselves.

Economos wondered whether Florida could join the few states that had introduced their own regulations to protect workers from heat illness. She knew that it would be an uphill battle. Florida’s legislature was unfriendly to pro-worker regulation, particularly for migrants, who largely make up the state’s outdoor industries, including construction, landscaping, and agriculture. She anticipated the agricultural industry, which she had battled with for years, would try to stamp out any pro-worker reforms, as they had in the past.

First, Economos wanted to better understand the problem and document its impacts. In 2017, she helped set up a research study conducted by the Farmworker Association of Florida and Emory University’s School of Nursing, which found that 84 percent of the workers they monitored experienced symptoms of heat exhaustion, like headaches, dizziness, and nausea. More than a third developed acute kidney injury on at least one day of work, which researchers say can be caused by heat exposure, potentially leading to chronic kidney disease.

With their research in hand, the Farmworker Association consulted with other worker groups to draft a bill proposal. They decided that the rule would be voluntary, with no fines or enforcement mechanisms, hoping that by working with industry to address the problem their effort would be more favorable to the Republican majority. They found a Democratic lawmaker who was willing to sponsor the bill, which was first introduced in 2018. It recommended that outdoor workplaces provide access to water, rest, and shade for workers along with training and emergency medical plans to prevent fatalities.

The first two years it was proposed, the bill never had a hearing. Worker advocates tried to find a Republican sponsor hoping that this would encourage congressional leadership to at least consider the issue. They found a new senator named Ana Maria Rodriguez from Miami-Dade County, a bipartisan, Latino district, who was willing to carry the bill in 2020.

That same year, the legislation for student athletes was being heard for the first time and was garnering attention. After the flurry of media coverage about Zachary’s case, Giordano was able to get meetings with senators to share her story and recommend reforms. The FHSAA had said that without state legislation they had no mandate to act, so lawmakers began to create one. Within months, a bill was drafted that required schools to monitor temperatures and adjust practice routines to adapt to heat levels. It called for regular water and rest breaks, training for coaches about heat-illness prevention, and cold water immersion tubs to treat students for heat stroke onsite.

Karen Woodall, a lobbyist for the Florida Center for Fiscal and Economic Policy, who had been working on the heat-illness protection bill for outdoor workers, was watching the progress of the student athlete bill closely. She attended the committee hearings where it was first discussed and noticed that the committee members “were pretty outraged by what they heard.”

“I got up and said, ‘I know you’re talking about student athletes,” Woodall recalled, “‘but I want you to know that we have a bill about this very thing for outdoor workers.’”

It felt like the energy around the issue might provide the worker bill with much needed momentum. The AFL-CIO staged a press conference where outdoor workers and their children spoke about the impacts of heat in the workplace and the playing field. One high school athlete, whose father was a migrant farmworker, said he hoped his father would be seen as worthy of the same protections he had been given.

The bill for student athletes was approved by multiple committees. Representatives and school administrators debated the cost burden of mandating ice tubs and wet bulb globe thermometers, but the consensus was that a significant number of schools were failing to provide critical safety measures, the solutions were simple, and ignoring the issue would lead to more preventable deaths.

Giordano’s story was a major driver for the issue.

“You meet a parent that lost a son and that’s a pretty powerful emotional testimony to have,” said Senator Keith Perry, a Republican and the owner of a roofing business, who ended up sponsoring the student athlete bill. “That’s why we started to go ahead and run this bill. … This seemed like a really easy solution to a tragic problem.”

Three months after the Zachary Martin Act was introduced, the Florida legislature voted unanimously for Governor Ron DeSantis to sign it into law.

Meanwhile, the bill to protect outdoor workers went without a hearing for the third year in a row.

In 2022, with Senator Rodriguez’s support, the bill was heard for the first time in the Senate Agriculture Committee. Senator Perry was a member of the committee. As the owner of a roofing business, he took an interest in the issue. After hearing from workers, business owners, labor advocates, and the widow of a construction worker who died from the heat, he joined the six other members of the committee in voting for the bill.

The next day, it was sent to the Health Policy Committee, where it sat unaddressed until the legislative session ended.

When asked why the student bill had succeeded while the worker bill, calling for less strenuous protections, had failed, Perry equivocated, telling Grist that he did not remember the details of the worker bill that he had voted for. But, he said, typically students were in greater need of protection than adults, who were ultimately responsible for their own choices. Like many opponents of statewide protections for outdoor workers, Perry noted that OSHA already provides safety recommendations for avoiding heat injuries in the workplace — though it’s left up to individual businesses to act on them.

Anna Eskamani, a Democratic state representative who has repeatedly sponsored the worker bill in the House, sees it differently. “We have an anti-immigrant governor who demonizes all immigrants, but especially those that come to our state in search of work,” she said. “Farmworkers are targeted, especially in Florida, by political actors.”

The bill was reintroduced to the Agriculture Committee this year. A workers’ advocacy group called WeCount spearheaded an effort to take up the issue on the county level as well. They helped push for an ordinance in Miami-Dade County that would fine employers in agriculture and construction who failed to provide water and shaded rest breaks in dangerous heat conditions.

After a heat dome encircled the U.S. South last summer, organizers rallied large crowds to speak in favor of the ordinance at board hearings, and several prominent county officials, including County Mayor Daniella Levine Cava, pledged their support. But facing fierce industry opposition, county officials voted to table the bill, and state congressional leaders moved to preemptively block their decision. Last week, a bill was approved that will void any local ordinances that protect workers from heat. The bill says that if federal OSHA does not create a national heat standard by 2028, the state’s Department of Commerce will have to create a statewide standard. But it doesn’t specify what the standard will require or whether it will include enforcement mechanisms like fines.

WeCount’s policy director, Esteban Wood, believes that the bill is intended to block their efforts in Miami-Dade and dissuade citizens and local officials from pushing for protections, rather than ensuring the safety of the state’s outdoor workers.

“You become a little disillusioned with the process,” Wood said, noting that after years of resistance, it’s unlikely that the state legislature will pass a bill on its own that provides meaningful protections for workers. “It’s a symptom of a larger issue — of a lack of priority for the health and safety of workers.”

Since Zachary Martin’s death, Florida schools are now required to monitor temperatures to ensure that students are not exposed to unsafe conditions and that cold water immersion tubs are available in case of emergencies. Since it passed, no student athlete in the state has died from heat.

Since Clovis Excellent’s death, the legislature has taken no steps to protect outdoor workers from heat, while at least five more Florida workers have died from heat illness.

“I’m just a little incredulous that it hasn’t been passed yet,” said Giordano, who has recently begun to collaborate with WeCount in their efforts to pass protections for outdoor workers, while pushing for a national bill to protect student athletes.“If it’s hot, there should be water, and they should be able to take breaks,” she said, whether you are “working out for football or cheering, or someone working on a roof.

“What does that hurt?” Giordano said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline As heat becomes a national threat, who will be protected? on Mar 13, 2024.

As firefighters contained the largest wildfire in Texas history last week, the electricity provider for the state’s Panhandle region, Xcel Energy, announced some bad news: The wildfire, which burned more than a million acres of land and killed at least two people, seemed to have been caused by one of the utility’s electrical poles.

“Based on currently available information, Xcel Energy acknowledges that its facilities appear to have been involved in an ignition of the Smokehouse Creek fire,” the statement read, referring to the largest of several fires raging in the area. An investigation from the state’s forest management agency found that the fire began when a decayed wooden pole splintered and fell, sending sparks onto nearby grass. Photos obtained by Bloomberg News appear to show that the pole had been marked unsafe before the fire.

Seizing on this evidence, multiple landowners in the area have already filed lawsuits against the company — as have family members of the fire’s victims, seeking millions of dollars in damages. Xcel has denied that it was to blame for the historic fire: In the same statement, the utility said it “disputes claims that it acted negligently in maintaining and operating its infrastructure.”

The lawsuits are just the latest in a string of high-profile wildfire cases against major electrical utilities, whose flammable power lines are among the most common culprits for major fire events. California companies such as Pacific Gas & Electric and Southern California Edison have paid out billions of dollars to fire victims and insurance companies over the past decade. Earlier this month, a jury delivered a verdict against the Oregon utility PacifiCorp, which could owe victims billions of dollars. Xcel itself is fighting hundreds of lawsuits in Colorado over its similar role in the 2021 Marshall Fire near the city of Boulder. These lawsuits have hit utilities with huge charges that they have passed onto customers in the form of rate increases.

The emergence of the trend in Texas, a state that has avoided massive fire losses over recent years, underscores that wildfires are now a national threat to utilities, according to Karl Rábago, a former Texas utility regulator and expert on utility law.

“They’re not pivoting to the world in which we live,” he told Grist. “When we face these situations, we do have a legal system that will likely dole out a measure of pain. The sad thing is, after paying out a certain amount of money, the problem will become so ubiquitous, and so oft-repeating, that we will treat it as business as usual.”

As in many previous lawsuits, the question in Texas is what counts as negligence on the part of a utility. If the fact that Xcel knew the pole needed repairs but hadn’t yet repaired it is sufficient evidence of neglect, the company will likely be on the hook for a large share of the fire damages, which could amount to hundreds of millions. The state utility regulator requires companies to plan for emergencies, and Xcel has told the state in the past that it conducts rotating inspections of old poles. However, most experts agree that utilities need to do more, burying power lines or adding technology that allows for rapid and precise power shutoffs during fire weather.

“There is a recognizable negligence, at least, in the failure to ensure that the systems are not extremely vulnerable,” said Rábago. “If your pole [is] 40 years old, it’s probably gotten to be so weak that it’ll get knocked over in severe winds.” Other fires that broke out in the Texas Panhandle at the same time as the Smokehouse Creek Fire have also burned thousands of acres, but investigators haven’t yet determined the cause of those events.

Xcel declined to comment for this story.

Xcel’s subsidiary in the Texas Panhandle delivers power to around 400,000 customers over a vast and sparsely populated service area of around 50,000 square miles. Pacific Gas & Electric in California, by comparison, provides power to 16 million people across a service territory that isn’t much larger. On the other hand, the fire mostly burned open rangeland, destroying far fewer homes than the Marshall Fire or other urban blazes. That could keep the potential damages relatively low.

The Smokehouse Creek Fire and its companion blazes are the most devastating in Texas history, but there is some precedent for holding Lone Star State utilities accountable. Dozens of victims and insurance companies sued the much smaller Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative near Austin for failing to remove dead trees ahead of a 34,000-acre fire. The company and its tree-trimming contractor settled those cases over the following years, with the contractor paying $5 million as recently as 2020. The fire was the most destructive ever in Texas at the time, but the Panhandle complex is many times larger.

“The consequences of utility ignitions are larger than they used to be, and there’s an increasingly clear set of practices that utilities can take, which some do, to avoid these kinds of ignitions,” said Michael Wara, a senior research scholar at Stanford Law School and an expert on how climate change affects utilities. “This is creating a situation where juries are more likely to hold utilities liable when they cause these catastrophic fires, if they haven’t taken appropriate steps.”

Wara said the most cost-effective steps include installing more accurate weather stations and shutting off the power proactively during extreme weather events.

These lawsuits may become more common as climate change ratchets up the potential for massive fires in many parts of the country. The Texas Panhandle has always seen rangeland fires, but studies show that the state’s high plains now see an additional month of “fire weather” each year compared to the mid-20th century. The combination of high temperatures and high winds that started the Smokehouse Creek Fire will only get more common as the Earth continues to warm, which could mean more costly fires and more litigation.

Utilities in other states have responded to fire lawsuits by raising rates on customers and using the money to pay out settlements or upgrade their infrastructure. Most Texans purchase power through a controversial wholesale market that has come under criticism for jacking up prices during extreme weather, but Xcel’s system in the Panhandle isn’t part of that market, so the utility’s customers could see a direct rate increase depending on how the lawsuit shakes out.

The growing trend of utility lawsuits has started to make markets nervous. Warren Buffett, whose company Berkshire Hathaway owns the Oregon utility PacifiCorp, said in his annual letter to shareholders last month that “the regulatory climate in a few states has raised the specter of zero profitability or even bankruptcy … in what was once regarded as among the most stable industries in America.” The legendary investor referred to his failure to foresee this trouble as “a costly mistake.”

In an interesting twist, Buffett then speculated that this threat to utility profits may someday lead more areas to adopt public power models, where governments rather than corporations control electrical infrastructure.

“Eventually, voters, taxpayers, and users will decide which model they prefer,” he said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline In Texas, as in California, big fires lead to big lawsuits on Mar 13, 2024.

When Suwanna Gauntlett started working on conservation in Cambodia in the early 2000s, hundreds of hectares of rainforest were set ablaze every month to clear the land for illegal sales, and dozens of tigers and elephants had been killed.

Gauntlett had founded the Wildlife Alliance in 1994 to fight tiger poaching in the Russian Far East, and a decade later expanded the nonprofit’s work to India, Ecuador, Myanmar, and Thailand. In 2000, Cambodia was their next frontier, home to one of the last giant rainforests in Southeast Asia stretching across the country’s Southern Cardamom region — what Gauntlett described as a “remote and completely lawless province.”

“There were no rangers, no park headquarters, no ranger stations, no law enforcement at all in the area,” Gauntlett said in a 2016 interview with Mongabay. “It was literally the wild, wild west.”

Gauntlett spoke with the news outlet to celebrate the establishment of a new national park, which promised to protect more than a million acres of rainforest. It was a big victory for Gauntlett’s organization, and helped spur an even more expansive project in partnership with the Cambodian government to protect rainforests and sell carbon credits as corporate offsets to fund the work.

The project is part of the United Nations framework called REDD+, which stands for “‘Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries.” The idea is that countries can fund environmental protection projects by selling a project’s carbon credits to corporations.

But that project, known as the Southern Cardamom REDD+, has come under fire from the nonprofit Human Rights Watch, an international human rights watchdog.

In a report released February 28, Human Rights Watch investigators describe how the project by the Wildlife Alliance and Cambodia’s Ministry of Environment repeatedly violated the rights of the Indigenous Chong peoples who have called the Cardamom mountains home for centuries.

According to the authors, the Wildlife Alliance and Cambodian government embarked on the project without first consulting with the Indigenous peoples who lived there, violating their right under international law to free, prior, and informed consent to projects on their land. The report also outlines how Indigenous people were prevented from farming on their land and even thrown in jail for collecting resin from trees. “This is my livelihood and tradition, and I am doing nothing wrong,” a man referred to as Chamson in the report told investigators.

Luciana Téllez, lead author of the Human Rights Watch report, said the findings reflect a broader trend globally in which Indigenous peoples and other traditional communities manage some of the best-preserved landscapes globally but are repeatedly marginalized and discriminated against.

“The push to increase the areas that are under protected status is not matched by an impulse to recognize these minority groups’ rights. And we need to see the pace of both of these things match each other,” Téllez said. “We need to see conservation moving at the same rhythm as the move to recognize, protect, uphold the rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities.”

Overlooking Indigenous peoples while establishing conservation areas is a long-standing global problem. Settlers in the U.S. who saw the continent as a remote and lawless place established many national parks only after the removal of Indigenous peoples. But the practice continues across the globe: In Tanzania, the Indigenous Maasai people fled gunfire in 2022 to make way for a game reserve. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, park guards at Kahuzi-Biega National Park have killed Indigenous Batwa people in the name of conservation. Forced evictions are a feature, not a bug, of the practice known as fortress conservation: The United Nations estimates that since 1990, 250,000 people have lost their homes to make way for conservation projects.

In order to comply with international law, conservation projects like the Southern Cardamom REDD+ project should conduct thorough consultation with Indigenous peoples before projects begin. The report noted that for years, Wildlife Alliance and Cambodian government officials made key decisions about the conservation project, including mapping the area, applying for funding, and signing contracts in the region, before embarking on consultations.

Even the establishment of a national park in 2016 enclosed eight Chong communities before mapping or titling their traditional lands, the report found.

Protecting conservation land at the cost of Indigenous rights is a problem that’s expected to continue as countries face increasing pressure to combat climate change. At least 190 nations have pledged to conserve 30 percent of the Earth’s lands and waters by 2030, many of which are home to Indigenous peoples, and the United Nations’ REDD+ framework has added financial incentives to these conservation efforts.

But Téllez said major questions remain about who actually benefits from carbon offset projects. Human Rights Watch found that in 2021, Southern Cardamom REDD+ made $18 million from carbon credit sales to multinational corporations. At the same time, Indigenous peoples described to investigators that the Wildlife Alliance’s enforcement of the REDD+ program cost them their livelihoods, including forcing some to borrow money when they were unable to farm on their family land.

“Everybody is banned from entering the forest, but many people have farmland there,” a woman named Sothy told investigators. Another named Pov said, “Wildlife Alliance came to cut down the banana trees. There was no warning or discussion prior to the destruction.”

Téllez said a key problem is the lack of a legally binding benefit-sharing agreement to ensure that the communities affected receive a certain proportion of project funds. Wildlife Alliance and the Cambodian government had committed to complying with voluntary standards set by Verra, a company that sets quality-assurance standards on the voluntary carbon market. But Verra does not require that agreements be made with Indigenous communities to ensure they benefit financially. After learning of Human Rights Watch’s findings, Verra announced it would begin investigating the Southern Cardamom REDD+ project.

Wildlife Alliance says the report is misleading. “Many of the criticisms the report makes about the Southern Cardamom project conveniently fit the narrative HRW had already created as part of their advocacy on international carbon markets,” the Wildlife Alliance said in a statement on their website.

The organization published a video this week of one of its community managers, Sokun Hort, denying that anyone had been evicted and saying that Human Rights Watch ignored broad community support for the project. The Wildlife Alliance and Cambodia’s Ministry of the Environment did not respond to requests for comment on the report.

Téllez of Human Rights Watch said the report reflects what investigators heard in dozens of interviews. Even a Cambodian government official told Human Rights Watch that the Wildlife Alliance had been “harassing poor people just for collecting forest products.”

Téllez is concerned by the organization’s continued denial of the allegations.

“There isn’t an acknowledgment that some people have been harmed by the project, and there isn’t an acknowledgment that those people are entitled to remedy,” she said. “And so we will continue demanding accountability.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline New report slams carbon offset project in Cambodia for violating Indigenous rights on Mar 13, 2024.

According to a new study, the survival rate of rainforest seedlings is higher in natural forests than those that have been logged — even three decades following tree restoration projects.

An international team of researchers led by the United Kingdom’s University of Exeter tracked more than 5,000 seedlings in the Danum Valley Conservation Area and surrounding Ulu Segama landscape in North Borneo for one-and-a-half years, a press release from University of Exeter said.

The landscape contained natural forest as well as areas that had been logged 30 years earlier. Some had been restored with tree planting and other methods, while others were recovering naturally.

“Our findings suggest that seedlings are experiencing stress in logged forests. This could be due to changes to the canopy structure, microclimate and soil, with current restoration treatments insufficient to eliminate this stress. In particular, highly specialised species seem to struggle to survive, leaving communities with reduced species diversity compared to intact forest,” said Dr. David Bartholomew, who was based at University of Exeter while conducting the study and is now with Botanic Gardens Conservation International, in the press release.

Logged forests have reduced seedling density, reducing the probability for the next generation to emerge. David Bartholomew

Across the study region, a “mass fruiting” had been triggered by drought. It caused trees to drop their fruit all at once, followed by the emergence of new seedlings.

Early on, both the restored forest and the natural forest had relatively high seedling numbers in comparison with a forest recovering naturally from logging, which suggested fruit production was enhanced by restoration activities.

But seedlings in the restored forest had low survival rates. By the time the study was finished, the naturally recovering forest as well as the restored forest had similarly low seedling numbers. In the natural forest, however, seedling populations stayed higher.

The results demonstrated that forest regeneration may be affected by various factors contingent upon the restoration approach. For example, seedling survival in areas where planted trees have reached maturity and seed availability in sites that are naturally recovering from logging. The variations could have longer-term effects on how forests are able to perform carbon sequestration and other important ecosystem services.

“We were surprised to see restoration sites having lower seedling survival. After such a productive fruiting event in the restored forest, it’s disappointing that so few were able to survive – and to think what this might mean for the long-term recovery of different tree species,” said Dr. Robin Hayward, who conducted the research while pursuing a Ph.D. at the University of Stirling, according to the press release.

Even though it has been shown that restoration benefits biomass accumulation, the findings indicated that it is not yet enabling the full establishment of next-generation seedlings.

“Rainforests are complex systems and there are many possible explanations for our results. For example, animals that eat seeds – like bearded pigs – may be drawn into restored forest patches to eat the more abundant seeds and seedlings, rather than moving into adjacent poor-quality logged forest. In natural forests, animals potentially move more freely and so do not exhaust seed supplies in the same way,” said Daisy Dent of ETH Zürich and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama, in the press release.

Selective logging is widespread throughout the tropics, but long-term forest recovery is essential to the maintenance of high biodiversity and carbon stocks. Low seedling survival rates three decades later raise concerns about possible regeneration failure in future tree generations.

“Together, these results reveal there may be bottlenecks in recovery of particular elements of the plant community. We are now progressing this research into the various stages of the regeneration process – fruiting, germination, establishment and causes of mortality – to help understand which mechanisms are driving the patterns we have observed and how we can better assist forest regeneration and support the long-term sustainability of degraded forests,” said Dr. Lindsay F. Banin of the UK’s Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, in the press release.

The study, “Bornean tropical forests recovering from logging at risk of regeneration failure,” was published in the journal Global Change Biology.

It draws attention to the urgency of careful design, adaptive management and monitoring of restoration projects to ensure they are able to recover long-term biomass carbon and biodiversity. This is essential to meeting global targets like those set forth in the United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration and the Kunming-Montréal Global Biodiversity Framework.

Traits and characteristics in plants that determine plant functionality could be the answer to understanding low seedling survival rate, as they can show which resources plants are having a difficult time accessing.

The study found differing plant traits in intact forests and logged areas, which indicated that certain species may be having a hard time surviving in areas that have been disturbed, and some must adapt the way they grow. This could affect ecological functioning and biodiversity in the long-term.

“This study captures just 18 months after one fruiting event. Longer-term research is required to understand the full effects of historic disturbance, and how to enhance seedling survival,” the press release said. “Here, intact forests are dominated by a tree family, the Dipterocarpaceae, which along with many other tree families, fruits in large inter-annual episodes known as masting events. These cyclical events have important cascading effects on food availability for animal species.”

The post Rainforest Seedlings Grow Better in Natural Forests Than Restored Ones, Even After 30 Years, Study Finds appeared first on EcoWatch.

According to a new analysis by the Energy Information Administration (EIA), the United States has produced the most crude oil globally for six years in a row — more than any nation in history during that time.

In 2023, the daily average crude oil production in the U.S. was a record 12.9 million barrels, a press release from EIA said. Its production broke the previous global record set in 2019 of 12.3 million barrels. In December, the average U.S. crude oil production hit a monthly high of more than 13.3 million barrels per day.

“The crude oil production record in the United States in 2023 is unlikely to be broken in any other country in the near term because no other country has reached production capacity of 13.0 million b/d. Saudi Arabia’s state-owned Saudi Aramco recently scrapped plans to increase production capacity to 13.0 million b/d by 2027,” the EIA said.

Last year, the U.S., Saudi Arabia and Russia together produced 32.8 million barrels of oil per day — 40 percent of global production. Since 1971, the three nations have produced the most crude oil, with the next three biggest producers — Iraq, Canada and China — pumping out 13.1 million barrels combined, barely more than the U.S. total.

U.S. yearly crude oil production plateaued and began to decline overall for decades following a peak of 9.6 million barrels per day in 1970. In 2008, it hit a low of five million barrels a day.

“Crude oil production in the United States began increasing again in 2009, as producers increasingly applied hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling techniques, and has increased steadily since,” the press release said. “The only exception to U.S. production growth since 2009 was in 2020 and 2021, when demand and prices decreased because of the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Recently, crude oil production in eastern New Mexico and western Texas — a region known as the Permian Basin — have been behind natural gas and crude oil increases in the U.S.

In 2017, Russia produced the most crude oil. However, its production growth has since fallen behind the U.S. Russia’s average annual production peaked at 10.8 million barrels per day in 2019.

In November 2022, Russia announced production cuts, along with other members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries Plus (OPEC+). The following February, the country announced further voluntary cuts of half a million barrels a day.

“Although voluntary cuts have reduced recent production in Russia, we believe sanctions and voluntary actions by companies in response to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine have been the primary cause of the cuts. Actual cuts to production appear to be smaller than anticipated, however, and we estimate that production in Russia declined by only 200,000 b/d in 2023,” explained the EIA.

Saudi Arabia’s average yearly production peaked at 10.6 million barrels a day in 2022 — 1.3 million barrels fewer than the U.S. total for that year. Last year, Saudi Arabia’s crude oil production declined by roughly 900,000 barrels daily due to cuts by OPEC countries, as well as additional voluntary cuts made by the oil-rich country meant to offset less growth in demand.

“Production in Saudi Arabia could not exceed the 2023 production volume in the United States because state-owned Saudi Aramco’s stated production capacity is 12.0 million b/d, with about 300,000 b/d of additional capacity from its share of the Neutral Zone area shared with Kuwait,” the press release said.

The post U.S. Has Produced More Oil Than Any Country in History for Six Consecutive Years appeared first on EcoWatch.

Researchers have discovered a variety of large plastic pieces in the guts of dead sea turtles found in the eastern Mediterranean. Some of these plastic items include bottle caps and a Halloween toy in the shape of a witch finger.

A team led by the University of Exeter and the North Cyprus Society for the Protection of Turtles (SPOT) examined 135 loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) that had died in North Cyprus, which has several nesting and foraging sites on beaches in the area. According to the study, many sea turtle deaths in the area are because of bycatch, and strandings also occur that may be related to interactions with the fisheries.

The researchers collected dead sea turtles from 2012 to 2022 and examined their guts for debris, including macroplastics, or plastic pieces larger than 5 millimeters.

In total, researchers found 492 macroplastic pieces in 42.7% of the turtles, and one individual turtle contained 67 of those macroplastic pieces. They published their findings in the journal Marine Pollution Bulletin.

Overall, the researchers noted that the plastic pieces ingested tended to be rectangular, sheetlike, hard or foam texture and clear or white in color. The most common types of macroplastics found were polypropylene, polyethylene and polyamide.

The researchers also recorded findings of plastic-like debris, including elastic and rubber. In one turtle, they found a witch finger toy made from rubber.

“The journey of that Halloween toy — from a child’s costume to the inside of a sea turtle — is a fascinating glimpse into the life cycle of plastic,” Emily Duncan, from the University of Exeter’s Centre for Ecology and Conservation at the Penryn Campus, said in a statement. “These turtles feed on gelatinous prey such as jellyfish and seabed prey such as crustaceans, and it’s easy to see how this item might have looked like a crab claw.”

According to the study authors, these findings could further support sea turtles as a bioindicator species, although more studies are needed. A bioindicator species is one that reveals changes to the health of an environment, such as the often-cited example of a canary in a coal mine.

As Brendan Godley, a professor at the University of Exeter who leads the Exeter Marine research group, explained, “Much larger sample sizes will be needed for loggerheads to be an effective ‘bioindicator’ species, and we recommend studies should also include green turtles — allowing a more holistic picture to be gathered.”

The post Bottle Caps, Halloween Toy and Other Plastics Found Inside Dead Sea Turtles in the Mediterranean appeared first on EcoWatch.

Despite the difficulties of recycling such a hefty household item, mattresses can be disposed of responsibly.

The post Recycling Mystery: Mattresses appeared first on Earth911.

If you’re a fan of chewing gum, there’s a big likelihood that you’re chewing single-use…

The post We Earthlings: Are You Chewing Single-Use Plastic? appeared first on Earth911.

The United States government said it is immune to 27 lawsuits filed by local and state governments, businesses, and property owners over the military’s role in contaminating the country with deadly PFAS, also known as “forever chemicals.” The lawsuits are a small fraction of the thousands of cases brought by plaintiffs all over the country against a slew of entities that manufactured, sold, and used a product called aqueous film-forming foam, or AFFF — an ultra-effective fire suppressant that leached into drinking water supplies and soil across the U.S. over the course of decades.

The Department of Justice asked a U.S. district judge in South Carolina to dismiss the lawsuits last month, arguing that the government can’t be held liable for PFAS contamination. Lawyers for the plaintiffs called the move “misguided” and said that dismissing the lawsuits would extend an ongoing environmental catastrophe the Pentagon helped create.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, commonly known by the acronym PFAS (pronounced PEA’-fass), were invented by the chemical giant DuPont in the 1940s. DuPont trademarked the chemical as “Teflon,” which many Americans came to know and love for its use in nonstick cookware in the back half of the 20th century. 3M, another industry behemoth, quickly surpassed DuPont as the world’s largest manufacturer of PFAS, which have also been used in makeup, food packaging, clothing, and many industrial applications such as plastics, lubricants, and coolants.

Unfortunately, PFAS cause a host of health problems. PFAS have been linked to testicular, kidney and thyroid cancers; cardiovascular disease; and immune deficiencies.

The Department of Defense became involved in PFAS development in the 1960s. In response to a number of deadly infernos on military ship decks, the Navy’s research arm, the Naval Research Laboratory, collaborated with 3M on a new kind of firefighting foam that could put out high-temperature fires. The foam’s active ingredient was fluorinated surfactant, otherwise known as perfluorooctane sulfonic acid, or PFOS — one of thousands of chemicals under the PFAS umbrella. Internal studies and memos show that 3M became aware that its PFAS products could be harmful to animal test subjects not long after the foam was patented.

Starting in the 1970s, every Navy ship — and, soon, almost every U.S. military base, civilian airport, local fire training facility, and firefighting station — had AFFF on-site in the event of a fire and to use for training. Year after year, the foam was dumped into the ocean and on the bare ground at these sites, where it contaminated the earth and migrated into nearby waterways. The chemicals, which do not break down naturally in the environment, are still there today. According to the nonprofit Environmental Working Group, there are 710 military sites with known or suspected PFAS contamination across the U.S and its territories including Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

The Department of Defense, or DOD, has been under growing pressure from states and Congress to clean up these contaminated sites. But it has been slow to do so, or even to acknowledge that PFAS, which has been found in the blood of thousands of military service members, pose a threat to human health. Instead, the DOD, which is required by Congress to phase out AFFF in some of its systems, doubled down on the usefulness of the chemicals as recently as 2023. “Losing access to PFAS due to overly broad regulations or severe market contractions would greatly impact national security and DOD’s ability to fulfill its mission,” defense officials wrote in a report to Congress last year.

Meanwhile, people living near military bases — and members of the military — have been getting sick. The lawsuits filed in the U.S. District Court in South Carolina, which were brought by farmers and several states, seek to make the government pay for the water and property contamination the DOD allegedly caused.

Even if these lawsuits are allowed to proceed, experts told Grist they are not likely to be successful. That’s because they rely on the 1946 Federal Tort Claims Act, a law that allows individuals to sue the federal government for wrongful acts committed by people working on behalf of the U.S. if the government has breached specific, compulsory policies.

But the Federal Tort Claims Act has loopholes. One of these loopholes, called the “discretionary function” exemption, states that federal personnel using their own personal judgment to make decisions should not be held liable for harms caused. The U.S. government is arguing that members of the military were using their discretion when they began requiring the use of AFFF and that no “mandatory or specific” restrictions on the foam were violated. “For decades military policy encouraged — rather than prohibited — the use of AFFF,” the Department of Justice wrote in its motion to dismiss the cases.

“Every decision has some discretion to it,” said Carl Tobias, a professor at the University of Richmond School of Law, noting that the discretionary function exemption could be applied to virtually any decision made by a federal employee. “But I don’t think anyone, except maybe the manufacturers of PFAS, had much of an inkling that it was so harmful,” he said. 3M and DuPont did not reply to Grist’s requests for comment.

In its motion to dismiss, the government made another argument that experts told Grist is likely to be successful. The Pentagon has the authority under the 1980 Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act — better known as the Superfund Act — to clean up its own contaminated sites. The Environmental Protection Agency hasn’t classified PFAS contamination as “hazardous contamination” yet, but the DOD says it is already spending billions to investigate and control PFAS at some of its bases. Because the military is voluntarily exercising its cleanup authority under the Superfund Act, its lawyers said in the motion, it should not be held liable for PFAS contamination.

Lawyers for the plaintiffs and the defendants declined requests for comment, citing the ongoing legal proceedings.

The U.S. government is the only defendant involved in the PFAS lawsuits that is likely to enjoy immunity. Already, 3M, DuPont, and other chemical companies, faced with the threat of high-profile trials, have opted to pay out historic, multibillion-dollar settlements to water providers that alleged the companies knowingly contaminated public drinking water supplies with forever chemicals. And the judge presiding over the enormous group of AFFF lawsuits has hundreds of other cases to get through that were not brought by water providers. These include personal injury and property damage cases, as well as those seeking to make PFAS manufacturers pay for medical monitoring for exposed populations.

The scale of the litigation is a clear indication that communities around the U.S. are desperate to find the money to pay for PFAS cleanup — the full cost of which is not yet clear, but could be as much as $400 billion. “We can’t even imagine what it would cost,” Tobias said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Pentagon tries to dodge PFAS lawsuits over a product it helped invent on Mar 12, 2024.