Who doesn’t like to start the day with a delicious cup of coffee or tea?…

The post 10 Sustainable Choices for Tea, Coffee, and Yerba Mate appeared first on Earth911.

Category Added in a WPeMatico Campaign

Who doesn’t like to start the day with a delicious cup of coffee or tea?…

The post 10 Sustainable Choices for Tea, Coffee, and Yerba Mate appeared first on Earth911.

This story is part of Record High, a Grist series examining extreme heat and its impact on how — and where — we live.

On any given summer day, most of the nation’s farmworkers, paid according to their productivity, grind through searing heat to harvest as much as possible before day’s end. Taking a break to cool down, or even a moment to chug water, isn’t an option. The law doesn’t require it, so few farms offer it.

The problem is most acute in the Deep South, where the weather and politics can be equally brutal toward the men and women who pick this country’s food. Yet things are improving as organizers like Leonel Perez take to the fields to tell farmworkers, and those who employ them, about the risks of heat exposure and the need to take breaks, drink water, and recognize the signs of heat exhaustion.

“The workers themselves are never in a position where they’ve been expecting something like this,” Perez told Grist through a translator. “If we say, ‘Hey, you have the right to go and take a break when you need one,’ it’s not something that they’re accustomed to hearing or that they necessarily trust right away.”

Perez is an educator with the Fair Food Program, a worker-led human rights campaign that’s been steadily expanding from its base in southern Florida to farms in 10 states, Mexico, Chile, and South Africa. Although founded in 2011 to protect workers from forced labor, sexual harassment, and other abuses, it has of late taken on the urgent role of helping them cope with ever-hotter conditions.

It is increasingly vital work. Among those who labor outdoors, agricultural workers enjoy the least protection. Despite this summer’s record heat, the United States still lacks a federal standard governing workplace exposure to extreme temperatures. According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, or OSHA, the agency has opened more than 4,500 heat-related inspections since March 2022, but it does not have data on worker deaths from heat-related illnesses.

Most states, particularly those led by Republicans, are loath to institute their own heat standards even as conditions grow steadily worse. In lieu of such regulation, the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, through its Fair Food Program, has adopted stringent heat protocols that, among other things, require regular breaks and access to water and shade. Such things are essential. Extreme heat killed at least 436 workers of all kinds, and sickened 34,000 more, between 2011 to 2021, according to NPR. Some believe that toll is much higher, and efforts like those Perez leads are providing a model for others working toward broader and more strictly enforced safeguards.

“We look to [the Fair Food Program] for best practices in terms of how can agricultural employers already begin to implement these kinds of protections,” said Oscar Londoño, the executive director of WeCount, which has been pushing for a heat standard in Miami-Dade County. “But we also believe that it’s important to have regulations and forcible regulation that covers entire industries.”

The Fair Food Program works with 29 farms, which raise more than a dozen different crops, and the buyers who rely upon them. In exchange for guaranteeing workers basic rights, participating growers and buyers, including Walmart, Trader Joe’s, and McDonald’s, receive a seal of approval that signals to customers that the produce they are buying was grown and harvested in fair, humane conditions.

To protect workers, the guidelines require 10-minute breaks every two hours and access to shade and water. The program also extended the time frame during which those things must be offered, from five months to eight, reducing the amount of time that workers are exposed to the worst heat of the year. Growers also must be aware of the signs of heat stress and monitor workers for them. Such steps are vital, particularly in humid conditions, to prevent acute heatstroke and safeguard employees’ long-term health. Repeated exposure to extreme temperatures can cause kidney disease, heat stroke, cardiovascular failure, and other illnesses.

“Having time to rest and cool down is very important to reduce the risk of death and injury from heat stress, because the damage that heat causes to the body is cumulative,” said Mayra Reiter, director of occupational safety and health at the advocacy organization Farmworker Justice. “Workers who are not given rest periods to recover face greater health risks.”

Such risks were very real for Perez, who worked various vegetable farms around Immokalee and along the East Coast before becoming an educator and advocate. Because most farmworkers are paid according to how much they harvest, few feel they can spend a few minutes in the shade sipping a beverage.

“The difficulty of the work makes you feel like it takes years off your life,” Lupe Gonzalo, a member of Coalition of Immaokalee Workers, wrote in a public blog post. High humidity makes things worse, and those who rely upon employer-provided housing often find no relief after a day in the fields because many accommodations lack air conditioning, she wrote.

Abusive conditions can compound the deadly conditions. A 2022 investigation by the Department of Labor revealed poor conditions, including human trafficking and wage theft, at farms across South Georgia. Two workers experienced heat illness and organ failure, and others were held at gunpoint to keep them in line as they labored.

Many were workers holding H-2A visas in a program that has its roots in the Mexican Farm Labor Program, launched in 1942, that sponsored seasonal agricultural workers from Mexico. (Currently, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security issues those visas.) Because of their reliance on employers for housing, visa sponsorship, and employment, many workers experience abuse, an investigation by Prism, Futuro Media, and Latino USA found earlier this year.

It doesn’t help that federal labor law, including the National Labor Relations Act, doesn’t cover agricultural workers in the same way it protects employees in other sectors, said James Brudney, a professor of labor and employment law at Fordham University. Additionally, language barriers, fear of retaliation, and workers who come from a variety of backgrounds and cultures keep many from speaking out.

Perez remembers having only bad options for dealing with adverse working conditions: Deal with it, complain and risk being fired, or quit. The Fair Food Program gives workers recourse he never had, and builds on protections against forced labor, sexual harassment, and other abuses it has achieved with workers, growers, and buyers, which have agreed not to buy from farm operators with spotty records, since 2011.

Workers are regularly informed of their rights, and violations can be reported to the Fair Food Program through a hotline for investigation. Heat-related complaints have grown increasingly common in recent years, and often lead to a confidential arbitration process. Such inquiries may lead to mandatory heat safety training and stipulations growers must abide by. Findings of more serious allegations, such as sexual harassment, can lead to a grower being suspended or even removed from the program. Such efforts protect workers, hold employers accountable, and allow the program to know what’s most impacting laborers, said Stephanie Medina, a human rights auditor with the Fair Food Standards Council.

“With the record heat, every summer has definitely, I think, gotten a lot more difficult for workers out there,” Medina said. “I think that is one of the reasons why we put so much emphasis on getting the heat stress protocols together and implemented in the program.”

Growers must report every heat-related illness or injury, which is investigated by Medina’s team or an outside investigator depending on severity. Her team visits every participating grower annually. Many of them go beyond the program’s requirements to ensure worker safety, by, say, providing Gatorade and snacks and regularly checking in on those who have experienced heat-related illness, she said. Workers, too, are being more assertive in protecting themselves, reporting any violations because they know they cannot be retaliated against.

Though no growers or farmer’s associations responded to Grist’s requests for comment, some at least appear happy with the organization’s work. “The Fair Food Program is giving us structure and is a tool for better understanding in a workplace that is multicultural and multiracial,” Bloomia, a flower producer and FFP participant, said in a statement on the program’s website.

Still, some farmworkers’ organizations, while supportive of the program’s work, doubt that farm-by-farm solutions will ever be enough to protect a majority of farmworkers. Jeannie Economos, of the Farmworkers’ Association of Florida, said comprehensive policy-level solutions are required. She noted that even in Florida nurseries, greenhouses, and other growers of ornamental plants employ thousands of people who are not yet covered by the Fair Food Program. Although they one day may be, federal, state, and local regulations are needed to ensure sweeping safety reforms.

“So what do we think of the Fair Food Program? It’s good,” she said. “But it’s not far-reaching enough.”

Other campaigns are working toward legislative solutions. An effort called ¡Que Calor! in Miami-Dade County, led by WeCount, has been pushing the issue for years, and in many ways is inspired by what the Coalition of Immokalee Workers has accomplished, Londoño told Grist.

“Miami-Dade is on the verge of passing the first county-wide [standard] in the country, and it would protect more than 100,000 outdoor workers in both agriculture and construction,” he said “In the absence of a federal rule, and in the absence of state protections, local governments can play a foundational role in piloting policies that states and the entire federal government can take on.”

¡Que Calor!, has, like the Fair Food Program, been led by workers. Including them in drafting policies can help ensure they are effective because “they know what their risks and the threats to their well being are better than anyone,” Brudney, the Fordham University professor, said

Yet even jurisdictions with strict labor laws can see their protections undercut because they often rely on employees, who may face reprisals, to report violations. Miami-Dade’s proposal skirts that by creating a county Office of Workplace Health with broad powers to receive complaints, initiate inspections, interview workers, and adjudicate investigations.

Amid such victories and a mounting need to protect workers, the Fair Food Program plans to expand its reach. It has cropped up at tomato farms in Georgia and Tennessee; crept up the East Coast to lettuce, sweet potato, and squash farms in North Carolina, New Jersey, Maryland, and Vermont; and sprouted on sweet corn farms in Colorado and sunflower farms in California. Organizers from the Fair Food Program have in recent weeks met with growers and workers in Chile eager to bring its efforts there.

The organization hopes to see its principals embraced more widely, and continues to pressure more companies, including Wendy’s and the Publix supermarket chain, to buy into the effort. Medina says such an effort will require staffing up, but she’s confident in its chances of success.

Many growers willfully neglect the rights and needs of workers, making such efforts essential, Perez said. The need for victories like those already seen on farms that work with the program will only grow more acute as the planet continues to warm. Even if federal heat standards are adopted, Perez believes local worker-led accountability processes will still be needed to ensure growers follow the law.

“What we see the Fair Food Program as is both a method of education and a way to share information with workers about these risks,” he said, “and at the same time as a tool for workers to protect themselves against the worst effects of climate change on a day to day basis.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How Florida farmworkers are protecting themselves from extreme heat on Oct 27, 2023.

Step into the street in most any major city and an e-bike carrying a commuter, a messenger, or a delivery is sure to whiz by. The zippy machines, which use electric motors to achieve speeds of up to 28 mph, are increasingly ubiquitous, particularly in New York City.

Their popularity has exploded, with annual sales growing roughly tenfold between 2017 and 2022, according to data provided by the industry group People for Bikes — an increase propelled in part by state and local rebates and other incentives. That growth has been accompanied by an increase in rider injuries and, in some cases, bikes literally exploding.

The federal Consumer Protection Safety Commission, or CSPC, identified a fire hazard in almost half of the 59 e-bike incidents that it chose to investigate last year. It also estimated that there were nearly 25,000 emergency room visits for e-bike injuries more broadly in 2022. The two-wheelers also have been involved in a spate of high-profile fatalities in recent years, especially in the Big Apple.

“[E-bikes] gained momentum unexpectedly,” said Matt Moore, People for Bikes’ general and policy counsel, citing the pandemic as a key accelerant. The result, he explained, was a boom of new bikes and new companies. “That rapid entry into the market really led to a huge growth in very low quality products.”

Although mishaps seem to be growing more slowly than sales, they are prompting calls for manufacturers to have their products certified by the likes of UL Solutions. Last month, New York City became the first jurisdiction in the nation to require exactly that, some 10 months after the CSPC sent a letter to e-bike companies urging them to seek such certification.

“I urge you to review your product line immediately and ensure that all micromobility devices that you manufacture, import, distribute, or sell in the United States comply with the relevant [standards],” the letter read. “Failure to do so puts U.S. consumers at risk of serious harm and may result in enforcement action.”

The industry has responded. The relevant standard in the U.S. and Canada is UL 2849, which was established in 2020, and examines a bike’s electric drive system for fire risk, charging performance, and performance in extreme cold and other conditions. (Separate standards apply to the batteries and general mechanical components). “We have seen inquiries about [UL 2849] testing and certification go up substantially,” a representative of UL Solutions told Grist. The 13 companies that have achieved certification this year is nearly twice the number seen in 2022.

The hope is that certification steers people toward safer bikes, and ultimately leads to fewer accidents. The move toward certification, however, won’t happen quickly or without bumps.

“I think everyone in the industry is aligned that we need to do something,” said Heather Mason, president of the National Bicycle Dealers Association. “The disagreements come down to what.”

One issue is that many bike manufacturers already certify their bikes to the European benchmark, EN 15194, because they sell far more of them there. And while UL 2849 was based on its European counterpart and the two standards may eventually harmonize, significant discrepancies remain. For example, the European standard has lower power limits for the motor than in the U.S.

Tweaking a design to meet the UL2849 could add time and significant costs. Moore says developing and certifying a drive system can cost $200,000 or more and take years.

“Anytime there’s a change in regulation, and you raise that floor, there are compliance costs,” he said. “It’s a cost that the industry is more than willing to bear.”

UL Solutions wouldn’t say what certification costs, but said it is far less than Moore’s estimate and usually takes only a month or two and once it has received all of the components. Once a company’s drive system is certified, it can theoretically use that hardware in multiple models. For a large manufacturer, the cost per bike can be relatively minimal.

But there are also potholes on the road toward certification.

Small but reputable manufacturers, for instance, may find the cost prohibitive. And, more immediately, it will create an inventory backlog of bikes that already are built to high standards but not UL2849 and can’t be sold in New York City, where the requirement took effect September 16. A UL Solutions or other seal of approval also won’t address every safety concern.

“The highest risk factors are crashes or falls on roads,” said Chris Cherry, a civil engineering professor and e-bike expert at the University of Tennessee. “A certified battery, or certified something else, isn’t going to solve those problems.”

But certification will allow consumers to shop more discerningly. An e-bike that meets the UL standard could be identified with a mark cast into the product or a sticker (though there have been reports of counterfeits). Bike shops should be able to identify models that meet UL 2849 as well, as would a company’s website.

“The end goal,” said Moore, “is to remove unsafe products from the market.”

This story has been updated to clarify that it does not investigate all e-bike accidents.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline As e-bikes grow in popularity, so do calls for safety certification on Oct 27, 2023.

As plastic litter builds up in the environment, polluting landscapes and poisoning ecosystems, U.S. lawmakers have unveiled their “most comprehensive plan ever” to tackle the problem.

Three Democratic members of Congress on Wednesday introduced the Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act of 2023, a sweeping bill to reduce plastic production and hold companies financially responsible for their pollution. Previous iterations of the legislation were introduced in 2020 and 2021, but this year’s version includes stronger protections for communities that live near petrochemical facilities, more stringent targets for companies to reduce their plastic production, and stricter regulations against toxic chemicals used in plastic products.

“Our bill tackles the plastic pollution crisis head on, addressing the harmful climate and environmental justice impacts of this growing fossil fuel sector and moving our economy away from its overreliance on single-use plastic,” Representative Jared Huffman of California said in a statement. Huffman co-sponsored the bill with Senator Ed Markey of Massachusetts and Senator Jeff Merkley of Oregon.

As U.S. demand for fossil fuel-powered heating, electricity, and transportation declines, fossil fuel companies are pivoting to plastic and are on track to triple global plastic production by 2060. Meanwhile, plastic pollution has reached crisis levels as litter clogs the marine environment and microplastics continue to be found on remote mountain peaks, in rainfall, and in people’s hearts, brains, and placentas. Plastic production also releases greenhouse gas emissions and other pollutants that disproportionately affect marginalized communities.

Like the bill’s earlier versions, Break Free 2023 would establish a nationwide policy of “extended producer responsibility,” or EPR. Under this policy, plastic companies would pay membership fees to a centralized organization that’s responsible for meeting targets around post-consumer recycled content and source reduction — reducing the production of plastic. The bill also retains proposals to ban certain single-use plastic products, implement a national system offering people deposits for recycling their beverage bottles, increase post-consumer recycled content in plastic bottles, and place a moratorium on new or expanded petrochemical facilities, pending a federal review of their health and environmental impacts.

The new bill, however, sets more specific targets for source reduction. By 2032, it would require plastic producers to reduce the amount of plastic they make by 25 percent — by weight, as well as the number of plastic items — and then halve it by 2050, in line with nation-leading requirements set in California last year. The bill would also phase out a list of “problematic and unnecessary” types of plastic and plastic additives, including polyvinyl chloride, a kind of plastic whose main ingredient is a human carcinogen, and ingredients added to help plastics break down whose health effects are poorly understood.

To mitigate some of the harms of plastic production, Break Free 2023 folds in environmental justice requirements from a separate bill introduced in Congress last December, the Protecting Communities From Plastic Act. These include greater communication and community outreach requirements for petrochemical companies that want to open a new factory for plastic production or chemical recycling, in the event that the moratorium on new petrochemical facilities is lifted.

This is the third time that a version of the plastics bill has been introduced in Congress, and it faces unlikely odds of passage. “Sadly, the makeup of Congress has not changed significantly over the course of Break Free being introduced, and we’re not set up well to move this bill at this time as a comprehensive package,” said Anja Brandon, associate director of U.S. plastics policy for the nonprofit Ocean Conservancy.

But there are other ways for the bill to make an impact. Smaller sections could be turned into their own federal bills, or they could influence policies at the state and local level. Merkley has been exploring a separate bottle deposit bill that could draw from the Break Free proposal. Brandon also pointed to proposed bans on specific products like single-use plastic cutlery and plastic foam foodware, which would be easier to pass on their own than as part of the whole Break Free package.

The Plastics Industry Association, a trade group representing U.S. plastics companies, said in a statement that the new bill was “even worse and less collaborative” than the previous versions, adding that it would “negatively impact the American economy” and lead to more greenhouse gas emissions, since plastics are lighter than some alternative materials and require less fuel to transport. “Instead of one-sided proposals that don’t move us forward, we need to work together to craft sound policy that will actually help our environment,” Matt Seaholm, the organization’s president and CEO, said in a statement, although he didn’t specify which kind of policy the group supports.

Brandon, with Ocean Conservancy, invited the plastics industry to collaborate with the nearly 100 organizations that are backing the Break Free bill. “It’s time for them to get on board,” she said. “The onus is on those companies and those producers of this waste to join us at the table and be a part of the solution.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Democrats unveil ‘most comprehensive plan ever’ to address plastics problem on Oct 26, 2023.

A new editorial published in more than 200 health journals challenges health professionals and world leaders to look at global biodiversity loss and climate change as “one indivisible crisis” that must be confronted as a whole.

The authors of the editorial call separating the two emergencies a “dangerous mistake,” and encourage the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare a global health emergency, a press release from The BMJ said.

“The climate crisis and loss of biodiversity both damage human health, and they are interlinked. That’s why we must consider them together and declare a global health emergency. It makes no sense for climate and nature scientists and politicians to consider the health and nature crises in separate silos,” said Kamran Abbasi, editor in chief of The BMJ, in the press release.

The editorial, “Time to treat the climate and nature crisis as one indivisible global health emergency,” was published in journals all over the world, including The Lancet, East African Medical Journal, National Medical Journal of India, Medical Journal of Australia, JAMA and Dubai Medical Journal.

The climate crisis has exacerbated extreme weather, air pollution, rising temperatures and the spread of infectious diseases across the globe. The biodiversity and climate crisis impacts human health, with the most vulnerable and poorest communities bearing most of the burden, the authors wrote in the editorial.

Water quality has been damaged, causing an increase in disease spread. Ocean acidification has impacted marine life and the quality of seafood for billions of people.

“This indivisible planetary crisis will have major effects on health as a result of the disruption of social and economic systems — shortages of land, shelter, food, and water, exacerbating poverty, which in turn will lead to mass migration and conflict,” the authors wrote in the editorial.

Green spaces are essential for helping combat air pollution, cooling the air and ground and giving people the opportunity to connect with nature, get active and interact with each other, thereby reducing depression and anxiety.

At the 2022 United Nations Biodiversity Conference (COP 15), world leaders agreed to conserve a minimum of 30 percent of the land, oceans and coastal areas on Earth by 2030. However, the authors of the editorial said nature and climate scientists who supply the evidence for the conferences mostly work independently and many of the agreed-upon targets have not been fulfilled.

“Yet many commitments made at COPs have not been met. This has allowed ecosystems to be pushed further to the brink, greatly increasing the risk of arriving at ‘tipping points’ — abrupt breakdowns in the functioning of nature. If these events were to occur, the impacts on health would be globally catastrophic,” the authors wrote. “Even if we could keep global warming below an increase of 1.5°C over pre-industrial levels, we could still cause catastrophic harm to health by destroying nature.”

The authors argued that the risks, along with health impacts that are already occurring, point to the need for WHO to declare the nature and climate crisis together as an indivisible global health emergency at or before the May 2024 World Health Assembly.

“Tackling this emergency requires the COP processes to be harmonised. As a first step, the respective conventions must push for better integration of national climate plans with biodiversity equivalents,” the authors wrote in the editorial.

For the health of humanity, health professionals must advocate for the restoration of biodiversity and addressing of climate change, and political leaders need to take note of the health threats brought on by the global emergency, as well as the benefits that could be gained from tackling it.

“Health professionals are highly trusted by the public, and they have a central role to play in articulating this important message and advocating for politicians to recognise and take urgent action to address the global health emergency. Over 200 health journals are today sending an unequivocal message,” Abbasi said in the press release.

The post Time to Treat Climate and Biodiversity Crises as One Global Health Emergency, Major Editorial Argues appeared first on EcoWatch.

Gina Ramirez grew up hauling cases of bottled water from the store to her home on Chicago’s South East side. It was exhausting and expensive, but her family had no choice. The water from the tap in her home, like many others in her neighborhood, was contaminated with lead.

Lead is a powerful neurotoxin with irreversible impacts, which is why the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC, has designated this week as National Lead Prevention Week. Exposure can cause brain damage in early childhood, harm the fetuses of pregnant women, and trigger miscarriages. Even low levels of lead exposure can cause kidney problems and heart disease in adults. Like many other heavy metals, it accumulates in the body over time. There is no known safe level of lead exposure.

Families around the country — most infamously, in Flint, Michigan — are dealing with lead in their water infrastructure. But Chicago is a hotbed of contamination, with the highest number of lead service lines in the nation. Experts believe that over 400,000 lead pipes supply water to homes throughout the city. A recent independent analysis by the Guardian found that one in 20 Chicago homes had tap water exceeding federal lead contamination standards. A third of the 24,000 tests showed lead levels above those permitted in bottled water, and 71 percent of homes exceeded the level the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends as a maximum lead level for kids in schools.

Chicago was one of the last cities in the nation to stop installing lead service lines. The city mandated them in new construction until Congress outlawed the practice in 1986. The result is a vast network of lead pipes that still feed contaminated water to homes and families throughout the city. The fallout from this toxic legacy is everywhere. Thousands of families live with lead-contaminated tap water, and testing found that drinking fountains in schools and parks throughout the city also had high lead levels.

This poisoning of Chicago’s tap water has had multi-generational impacts. Like Ramirez, Crystal Guerra, a parent, artist, and activist, grew up in Chicago’s South Side. Her father worked in the city’s steel mills, and her mother was a teacher at a local elementary school. In 2019, she got a letter from the local hospital. Her 1-year-old son, who was still breastfeeding, had high blood levels of lead.

Guerra was shocked. “I had a healthy baby, and the next thing I knew, he had a high level of lead,” she says. “He was only a year old, and I couldn’t protect him from this. I was angry.” Doctors tracked her son’s lead levels and developmental milestones for the next several years. Thankfully, after the family began drinking filtered and bottled water, his most recent tests showed that the amount of lead in his blood had significantly dropped, and he has shown no developmental delays.

Driven by her personal experience, Guerra helped found Bridges Puentes, a collective that responds to community needs through art and activism. Vanessa Bly is another Chicago artist who helped found and run the organization. “We’re a low-income neighborhood with old houses,” she says. “We need the city to assist with fixing this issue.”

Ramirez, who now works as the Midwest outreach manager for the Natural Resources Defense Council, or NRDC, agrees. Ramirez’s parents are retired on a fixed income, and her mother has limited mobility. After decades of buying bottled water — which cost the family up to $600 per year — they decided to apply for a city program that replaces lead service lines for households below a certain income threshold. The complex and intimidating application process took over two years, but in June 2023, Ramirez finally saw the lead pipes that fed water to her childhood home replaced by the city. The process took six hours, and Ramirez estimates that it involved 20 different people. “I was impressed with how fast they replaced it, but I was also a bit overwhelmed at how many people and trucks showed up,” she says. “It was all for just one house.”

Other cities have found more efficient or effective approaches to the issue. In Newark, New Jersey, the city replaced almost 24,000 lead service lines in just three years at no cost to residents. The city and surrounding county raised bonds to pay for the replacements that are mostly covered by fees paid by the local port authority. Oscar Sanchez, a community planning manager with the Southeast Environmental Task Force, a Chicago-based environmental nonprofit, believes Newark’s strategic approach created the positive outcome. “One important tactic was that they worked on clusters, instead of just one house at a time,” he says. “If they found one house with a lead pipe, they just changed out the whole block.”

Another approach could be to put lead filters at locations using lead pipes for drinking water. This “filter first” approach is poised to be adopted in the state of Michigan, which will mandate filtered water in all schools and childcare centers. “They’ve pushed the filter first approach, and they’re being very strategic about prioritizing spaces where children spend many hours each day,” such as schools and daycare centers, says Sanchez. “A similar government-funded filter program in Illinois would be a really good solution to ensure people have access to clean water for the long-term.”

NRDC’s Safe Water team has worked on Chicago’s lead service line issue for many years, with campaigns ranging from grassroots community organizing and education to high-level policy and advocacy. In a recent NRDC poll, lead service lines were one of the top priorities for the Chicago community. “We need to put the approaches that have worked in other places, like Newark’s lead service line replacement program, into action here in Chicago,” Ramirez says.

The federal government is also finally taking action: The EPA is about to release an updated rule that tackles lead in tap water. Advocates are pushing for the agency to require all lead pipes to be removed within 10 years, and for water utilities to pay to replace the full pipe rather than shifting any of the costs to residents. These changes could force Chicago and other cities to accelerate their lead service line replacement.

But while the Biden administration has earmarked billions to address lead service lines, funding will be a challenge for Chicago. The city will only be able to access a small portion of the $15 billion in federal funding for lead service line replacement due to some technical red tape: The city is not designated as a disadvantaged community by the state of Illinois — a requirement to access more funding.

And due to Chicago’s specific construction requirements, permit fees, and other policies, replacing a single lead service line can cost up to $30,000 — a price tag far higher than virtually any other city — that is out of reach for many homeowners and renters. “I’m buying a house, and it has a lead service line,” says Ramirez. “I don’t qualify for the equity line replacement program and don’t have a bunch of extra money lying around, so I’m going to have to live with filtering and bottled water.”

Another hurdle for Chicago is the lack of trained technicians to replace the lead service lines—but this issue could be reframed as an opportunity. “We should use this to create employment for the disenfranchised communities that this issue has harmed,” says Brenda Santoyo, a senior policy analyst with the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization. “It’s a chance to work with local colleges to create a training program and a pipeline to get people into these trades and create good jobs. This is a large-scale problem, and we will need a workforce to solve it.” In Newark, the city worked with a local union to train local residents, many of whom were unemployed, to replace the city’s lead lines. Those trained employees now can use their new skills to help other cities replace their lead pipes.

The monumental scale and impact of Chicago’s lead service line issue means that the city, state, and federal government will need to work together to find a solution — and that support can’t come soon enough. “When I look at the shopping carts of families in my neighborhood, they’re all filled with cases of water,” says Ramirez. “We shouldn’t have to live this way, buying bottled water, not trusting our tap, and suffering from water-related health ailments. We have a right to healthy, clean water.”

Sign NRDC’s petition to the White House urging the Biden administration to remove lead service lines as quickly and as equitably as possible.

NRDC (Natural Resources Defense Council) is an international nonprofit environmental organization with more than 3 million members and online activists. Established in 1970, NRDC uses science, policy, law, and people power to confront the climate crisis, protect public health, and safeguard nature. NRDC has offices in New York City, Washington, D.C., Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago, Bozeman, MT, Beijing, and Delhi (an office of NRDC India Pvt. Ltd). Visit us at www.nrdc.org and follow us on Twitter @NRDC.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Toxic tap water: Corroded lead pipes supply water to families throughout Chicago on Oct 26, 2023.

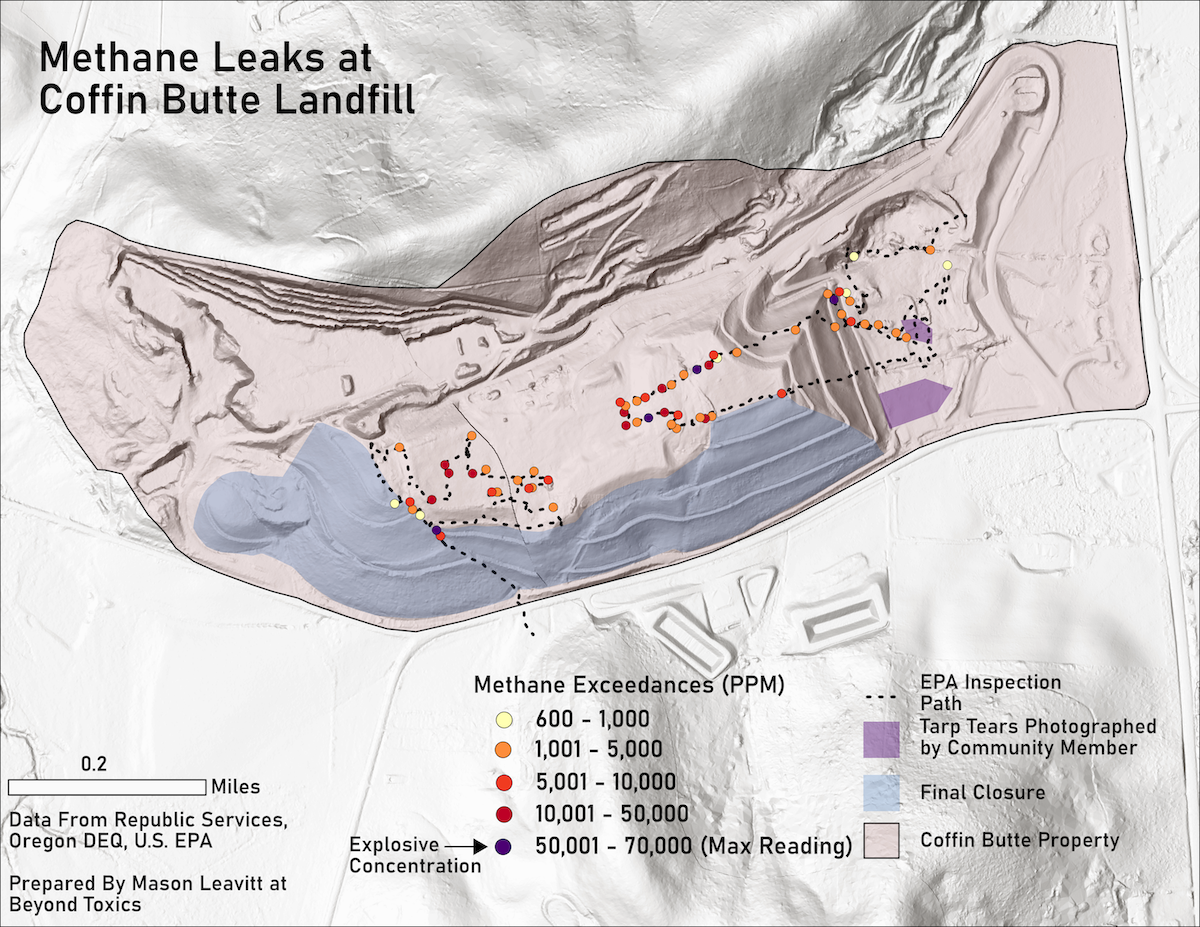

Landfills in Oregon and Washington repeatedly exceeded federal standards for methane emissions last year, according to documents obtained by an environmental group.

Although the Clean Air Act requires that large landfills operators keep methane concentrations below 500 parts per million, Environmental Protection Agency inspection reports from May and June 2022 show that this threshold was exceeded in dozens of readings taken at four landfills in Oregon and Washington. At one landfill near Corvallis, Oregon, there were so many exceedances that an inspector ran out of flags to mark them with. At another, the inspector’s measuring instruments maxed out, indicating what he described as “explosive” concentrations of methane.

Katherine Blauvelt, circular economy campaign director for the environmental group Industrious Labs, which obtained the documents through public records requests, said the reports highlight the need for better monitoring and mitigation of landfill methane emissions nationwide. These kinds of methane leaks are likely happening across the country, she said, much more frequently than the public knows, and regulators aren’t using the best tools to stop them.

“Everyone’s operating under the Windows 2000 system, and it’s time for an upgrade,” she said. “We’ve got to do better, because we’re in a climate emergency and methane is a super-pollutant.”

Methane, a greenhouse gas 84 times more powerful than carbon dioxide over its first 20 years in the atmosphere, is released from landfills by decomposing organic material like food scraps, cardboard, and yard trimmings. Already, EPA data pins landfills as the country’s third-largest source of anthropogenic methane emissions after oil and gas infrastructure and animal agriculture, and in many states — including all three on the West Coast — landfills account for 80 percent or more of all industrial methane emissions.

Large landfill operators can’t stop organic matter from releasing methane as it decomposes. But they are required by law to conduct quarterly monitoring of their facilities and prevent that methane from escaping into the atmosphere — in part due to safety concerns, since methane is highly combustible. When landfill operators find places where methane concentrations exceed 500 parts per million, they’re supposed to report it — usually to their state’s environmental authority — and take measures to bring that concentration down. These measures can include improving the covers that landfills are required to have — which often include tarps — or installing gas capture systems that transport the methane to a flare or a treatment center, where it can be used to generate electricity or converted into vehicle fuel.

Sometimes, federal inspectors from the EPA visit to take their own measurements. They walk a loop around the landfill and take periodic measurements with a tool called a “toxic vapor analyzer.” At minimum, they have to take measurements every 100 feet, but they also take measurements in places where they see potential signs of a methane buildup — for example, where air pressure appears to be lifting up a section of the landfill cover, or at a hole in the cover.

These measurements from the EPA don’t always match up with the landfill operators’ self-surveys.

For example, according to the EPA inspection reports seen by Grist, the company Republic Services found zero methane exceedances over five years of quarterly monitoring of its regional landfill in Roosevelt, Washington, and between zero and six exceedances in recent quarterly surveys of its Coffin Butte landfill near Corvallis, Oregon. But when the EPA visited these landfills in June 2022, an inspector documented 16 points of exceedance at the Roosevelt facility and more than 60 at the Corvallis one. More than two dozen locations across both landfills showed methane concentrations above 10,000 parts per million, more than 20 times higher than the Clean Air Act limit. At both landfills, the inspector noted visible signs of methane leakage, including areas of the landfill cover that were “inflated with and leaking out landfill gas.”

This was also the case at a Graham, Washington, landfill operated by the company Waste Connections, where the EPA inspector logged 38 points of exceedance and noted an “environmental concern and a safety hazard” caused by explosive levels of gas leaking out of the landfill cover. Another landfill near Seattle, operated by King County, showed just three methane exceedances, although one location had a methane concentration of 9,000 parts per million.

In response to Grist’s request for comment, Republic Services said it has “differing perspectives” on the EPA’s testing protocols and analyses from its inspections in 2022, and that it has “addressed the EPA’s observations” at both its Corvallis and Roosevelt facilities. King County said it made immediate repairs to the landfill cover to address the largest exceedance identified by the EPA, and that it “increased the frequency of synthetic cover inspections to identify any potential damage and repair it as soon as possible.” Waste Connections did not respond to Grist’s request for comment.

The EPA inspection reports appear to reflect the agency’s broader difficulties with quantifying and limiting landfill-based methane emissions nationwide. According to a recent study submitted to the journal Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics that has not yet undergone peer review, methane emissions from landfills could be 77 percent higher than the values reported by U.S. operators to the EPA, and the EPA itself has said that “widespread noncompliance” with federal rules for landfill-based methane releases may have contributed to “potentially tens of thousands of tons of unlawful emissions of greenhouse gases and other pollutants.” This August, the agency identified landfill methane as one of its three main climate-related enforcement priorities for 2024 to 2027.

Meanwhile, people living near landfills are increasingly concerned over the climate and safety impacts of these methane emissions. Kevin Kenaga, who lives near Republic Services’ Corvallis facility, said explosive methane leaks could make the landfill “really, really problematic” in case of a wildfire, since it’s flanked by forests. (Landfills can also start fires themselves; they frequently reach very high temperatures and have been known to spontaneously combust.) He and others have documented numerous holes in the landfill cover, some of which show weeds growing through them, or animal burrows.

To turn things around, environmental groups are pushing for more stringent requirements for landfill operators, beginning with better monitoring. Air-based monitoring, for example — performed by a drone — could be used to identify more leaks, more often than four times a year, and it could be combined with satellite imagery to identify where some of the biggest methane plumes are. These technologies already exist, and Blauvelt said they could be a “game-changer” if better applied to mitigating landfill methane emissions.

Blauvelt also called on regulators to create standards for the thickness and type of material used as landfill cover, since this cover is “the most important operational factor in slowing the release of methane.” She also said more landfill operators should be required to put gas capture systems in place, and on a faster timeline. Right now, many smaller landfills don’t have any requirements for gas capture, and the larger ones can drag their feet for five years before installing a system. They can “just sit there” emitting methane, she said.

Some of these changes may be in the works for Washington state, where the Department of Ecology is getting ready to propose a new rule fleshing out new requirements for the monitoring and mitigation of landfill-based methane emissions. That rule is expected to be finalized this fall. At the federal level, advocates are also awaiting updated landfill air quality rules from the EPA sometime in 2024. In response to Grist’s request for comment, the EPA said it already uses satellite imagery and “other airborne monitoring technologies” to identify facilities that may be noncompliant with federal law, though landfill operators are not required to use these technologies. The agency said it is “in the process of considering what, if any, next steps” it will take following its 2022 inspections in Oregon and Washington.

Perhaps the most effective way to address landfill methane emissions is to stop them from being created in the first place — and that means keeping organic material out of landfills, for example, by reducing food waste or diverting it to municipal composting programs. According to one estimate, sorting and treating organics separately from other trash can reduce landfill methane emissions by 62 percent.

Washington state recognized this strategy in a law passed last year to reduce organic waste disposal by 75 percent by 2030, and environmental groups say it should be prioritized elsewhere too — like in Corvallis, Oregon. “This community really wants alternatives to landfills,” said Mason Leavitt, a GIS and spatial data coordinator at the Oregon-based nonprofit Beyond Toxics, referring to residents living near Republic Services’ landfill. “We’re really focused on ways to do that, and diverting organics is going to be a huge one.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Landfills in Washington and Oregon leaked ‘explosive’ levels of methane last year on Oct 26, 2023.

Dan Zauderer and his in-laws had eaten plenty of pizza one evening in early October, and they still had seven slices left. What to do? “Well, we could just chuck it,” Zauderer thought. Instead, he and his fiancée wrapped the slices in plastic wrap, slapped labels on them with the date, and walked the leftovers a little more than a block down the road to a refrigerator standing along 92nd Avenue in New York City’s Upper East Side.

That fridge is one among many “community fridges” across the country that volunteers stock with free food — prepared meals, leftovers, and you name it. Zauderer had helped set a network up in New York City during the pandemic as a way to reduce waste and fight hunger. The idea came about when he was a middle school teacher looking to provide short-term help to students whose families couldn’t afford food. He stationed the first fridge in the Bronx in September 2020. That one, the Mott Haven Fridge, was hugely popular, and it motivated Zauderer to expand. Since then, he has helped plug in seven more fridges in the Bronx and Manhattan, including the one where he dropped off his leftover pizza.

“It just blossomed into way more than I ever could have expected,” said Zauderer, who now works full-time at Grassroots Grocery, a food-distribution nonprofit he co-founded in New York.

It’s not just Zauderer’s project that has blossomed. Community fridges first cropped up a decade ago in a few isolated spots around the globe, then spread across the United States right after the pandemic started in 2020, when supply chains were crumbling, food prices were rising, and families across the country were struggling to find meals. At the time, the fridges were viewed as a creative response to an urgent need. But when the pandemic subsided, it became clear that the refrigerators — sometimes called freedges, friendly fridges, and love fridges — were more than a fad. Today, nonprofits and mutual aid groups are overseeing hundreds of fridges that bolster access to food in cities from Miami to Anchorage, Alaska.

The fridges also embody a straightforward solution to climate change. Each year, tens of billions of pounds of food, more than a third of what’s produced in the U.S., get tossed into trash bins. Most of those scraps end up in landfills, where they decompose and release methane, a powerful heat-trapping gas. The sheer quantity of the country’s combined waste makes it a major source of climate pollution: Food waste accounts for as much as 10 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. And more food is being thrown out than ever.

“There’s no solution to our climate problem that doesn’t also address food waste,” said Emily Broad Leib, director of the Harvard Food Law and Policy Clinic.

There are many ways to keep food out of landfills and on dinner tables. Companies are developing apps to connect people with donated goods, and food banks have been around for decades. Experts say raising awareness and changing policy around things like expiration dates on food packaging, which can be arbitrary, would help, too. But fridges are especially effective when other solutions fall short. Though food banks are great for storing large amounts of shelf-stable items like canned vegetables, they’re not well-equipped to handle food that doesn’t last as long and turns up in small amounts— a pizza slice here, a sandwich there. Those remnants make up much of the country’s food waste, about 40 percent, and that’s where community fridges excel. “These are just a really elegant solution to that,” Broad Leib said.

The fridges also offer a degree of anonymity for those in need that’s hard to find at more traditional food distribution centers, like food pantries. People don’t have to sign up or prove their eligibility to use them. “The whole point is dignified, anonymous access,” Zauderer said. “We’re not the arbiters of how much to take.”

In Chicago, an artist named Eric Von Haynes co-founded a fridge network called The Love Fridge in 2020. Today, he helps oversee more than 20 love fridges, each decorated with eye-popping colors and phrases like “Free food for all!” According to Von Haynes, the fridges are filled, cleaned, and maintained by hundreds of volunteers. He estimates that thousands of pounds of food move through them each month.

One concern that researchers have with projects that repurpose food is that they require additional resources, like transportation and electricity. “Rescuing [food] still comes at a cost,” said Kathryn Bender, a professor and food waste researcher at the University of Delaware.

But community fridges are about as low-key and energy efficient as solutions get. Zauderer didn’t burn any fossil fuels to walk his pizza to the fridge near his apartment. And the Love Fridge, which acquires only used refrigerators, powers two of them with solar panels — a vision that Von Haynes has for more to come.

Even a fridge that draws electricity from a coal-powered grid uses less energy each day than a single cell phone, said Dawn King, who researches food waste and policy at Brown University. “Is it worth using greenhouse gas emissions to plug in a refrigerator so people can eat food that otherwise would have gotten wasted? Hell yes it is.”

Other challenges include navigating concerns about rotten or unwanted food, making sure fridges are working properly, especially during increasingly hot summers, and keeping them stocked. Ernst Bertone Oehninger, who helped set up what may have been the first “freedge” in the U.S. in 2014 in Davis, California, has learned that some items don’t belong in them.

“Think about a half-eaten burger. That’s a no-go,” said Oehninger. “But this is very rare. Most people bring good leftovers.” Like Zauderer’s pizza.

A fridge in Austin, Texas, once went missing. It had been “borrowed” by someone who wanted to keep beers cold for an event at South by Southwest, according to Kellie Stiewert, an organizer at the ATX Free Fridge project. But such shenanigans are rare. That the fridges can be placed with a property owner’s permission just about anywhere — in front of a taqueria, a person’s home, an office building — is what makes the concept “beautiful,” Stiewert said.

Organizers say keeping the fridges full is one of the toughest tasks. People sometimes gather to pick up items within minutes of a fridge getting stocked. “When I first get volunteers to do food distro with me, I’m always waiting for them to recognize how fast the food goes,” Von Haynes said. “It’s really hard to explain to people.”

As for Zauderer’s pizza slices: “They definitely weren’t there the next day.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Community fridges don’t just fight hunger. They’re also a climate solution. on Oct 26, 2023.

In an era defined by rapid technological development, the exponential growth of electronic devices creates…

The post The Right to Repair is Crucial to E-Waste Reductions appeared first on Earth911.

The Environment Committee of European Parliament has voted to ensure sustainable use of pesticides and reduce their use by at least half by 2030.

Members of Parliament (MEPs) voted to also reduce the use of “more hazardous products” by 65 percent as compared to the average from 2013 to 2017, a press release from European Parliament said.

“This vote brings us one step closer to significantly reducing chemical pesticide use by 2030. It is very positive that we were able to agree on feasible compromises in an ideologically charged and industry-dominated discussion,” said MEP Sarah Wiener, rapporteur on sustainable use of pesticides, in the press release.

MEPs are asking each member nation to adopt their own national strategies and targets based on products’ hazard levels, amount of the substances sold annually and their affected agricultural area. The European Commission will then review them and decide if targets are on track to meet EU 2030 goals or need to be modified.

Additionally, EU member countries must have rules for at least five crops where reducing chemical pesticide use would have the most impact.

MEPs want to ban toxic pesticides in “sensitive areas,” other than those authorized to be used for biological control and organic farming, plus a surrounding buffer zone. Examples of these areas are parks, public paths, recreation areas, playgrounds and Natura 2000 areas throughout Europe.

“Practical solutions have been found for example on sensitive areas where member states can make exceptions if needed. It was particularly important for me to ensure that independent advice on preventive measures based on integrated pest management would be offered free of charge to European farmers,” Wiener said in the press release.

EU nations are obligated to ensure toxic pesticides are used only as a “last resort,” according to the rules in Integrated Pest Management.

In order to provide farmers with better access to alternative substances, MEPs want the commission to set a target date for increasing sales of lower-risk pesticides that is six months following the start of the new regulation.

Any changes that arise from the new rules would happen gradually to minimize impacts on food security.

MEP Marie Arena, a Belgian Socialist politician, said the result would benefit both the environment and farmworkers, as “abusive use of pesticides makes people sick,” as well as wiping out bee populations, AFP reported.

The commission must look at the differences in pesticide use on imported agri-food and agricultural products in comparison to EU produce by December of 2025, and, if necessary, propose measures to make sure imports are up to EU standards. The export of pesticides banned in the EU would also be prohibited.

Parliament’s new mandate is scheduled to be adopted during the plenary session of November 20 to 23 of this year. It will then begin negotiations with EU member nations.

The proposal is one of a group of measures aimed at reducing the EU food system’s environmental footprint, as well as mitigating economic losses caused by biodiversity loss and climate change.

The post EU Votes to Cut Pesticide Use in Half by 2030 appeared first on EcoWatch.