Honeywell International is one of the largest companies in the world, ranking 115th in the…

The post Earth911 Podcast: Honeywell’s Chief Sustainability Officer, Dr. Gavin Towler, On Accelerating ESG Efforts appeared first on Earth911.

Honeywell International is one of the largest companies in the world, ranking 115th in the…

The post Earth911 Podcast: Honeywell’s Chief Sustainability Officer, Dr. Gavin Towler, On Accelerating ESG Efforts appeared first on Earth911.

In Florida, the effects of climate change are hard to ignore, no matter your politics. It’s the hottest state — Miami spent a record 46 days above a heat index of 100 degrees last summer — and many homes and businesses are clustered along beachfront areas threatened by rising seas and hurricanes. The Republican-led legislature has responded with more than $640 million for resilience projects to adapt to coastal threats.

But the same politicians don’t seem ready to acknowledge the root cause of these problems. A bill awaiting signature from Governor Ron DeSantis, who dropped out of the Republican presidential race in January, would ban offshore wind energy, relax regulations on natural gas pipelines, and delete the majority of mentions of climate change from existing state laws.

“Florida is on the front lines of the warming climate crisis, and the fact that we’re going to erase that sends the wrong message,” said Yoca Arditi-Rocha, the executive director of the CLEO Institute, a climate education and advocacy nonprofit in Florida. “It sends the message, at least to me and to a good majority of Floridians, that this is not a priority for the state.”

As climate change has been swept into the country’s culture wars, it’s created a particularly sticky situation in Florida. Republicans associate “climate change” with Democrats — and see it as a pretext for pushing a progressive agenda — so they generally try to distance themselves from the issue. When a reporter asked DeSantis what he was doing to address the climate crisis in 2021, DeSantis dodged the question, replying, “We’re not doing any left-wing stuff.” In practice, this approach has consisted of trying to manage the effects of climate change while ignoring what’s behind them.

The bill, sponsored by state Representative Bobby Payne, a Republican from Palatka in north-central Florida, would strike eight references to climate change in current state laws, leaving just seven references untouched, according to the Tampa Bay Times. Some of the bill’s proposed language tweaks are minor, but others repeal whole sections of laws.

For example, it would eliminate a “green government grant” program that helps cities and school districts cut their carbon emissions. A 2008 policy stating that Florida is at the front lines of climate change and can reduce those impacts by cutting emissions would be replaced with a new goal: providing “an adequate, reliable, and cost-effective supply of energy for the state in a manner that promotes the health and welfare of the public and economic growth.”

Florida politicians have a history of attempting to silence conversations about the fossil fuel emissions driving sea level rise, heavier floods, and worsening toxic algae blooms. When Rick Scott was the Republican governor of the state between 2011 and 2019, state officials were ordered to avoid using the phrases “climate change” or “global warming” in communications, emails, and reports, according to the Miami Herald.

It foreshadowed what would happen at the federal level after President Donald Trump took office in 2017. The phrase “climate change” started disappearing from the websites of federal environmental agencies, with the term’s use going down 38 percent between 2016 and 2020. “Sorry, but this web page is not available for viewing right now,” the Environmental Protection Agency’s climate change site said during Trump’s term.

Red states have demonstrated that politicians don’t necessarily need to acknowledge climate change to adapt to it, but Florida appears poised to take the strategy to the extreme, expunging climate goals from state laws while focusing more and more money on addressing its effects. In 2019, DeSantis appointed Florida’s first “chief resilience officer,” Julia Nesheiwat, tasked with preparing Florida for rising sea levels. Last year, he awarded the Florida Department of Environmental Protection more than $28 million to conduct and update flooding vulnerability studies for every county in Florida.

“Why would you address the symptoms and not the cause?” Arditi-Rocha said. “Fundamentally, I think it’s political maneuvering that enables them [Republicans] to continue to set themselves apart from the opposite party.”

She’s concerned that the bill will increase the state’s dependence on natural gas. The fossil fuel provides three-quarters of Florida’s electricity, leaving residents subject to volatile prices and energy insecurity, according to a recent Environmental Defense Fund report. As Florida isn’t a particularly windy state, she sees the proposed ban on offshore wind energy as mostly symbolic. “I think it’s more of a political kind of tactic to distinguish themselves.” Solar power is already a thriving industry that’s taking off in Florida — it’s called the Sunshine State for a reason.

Greg Knecht, the executive director of The Nature Conservancy in Florida, thinks that the removal of climate-related language from state laws could discourage green industries from coming to the state. (And he’s not ready to give up on wind power.) “I just think it puts us at a disadvantage to other states,” Knecht said. Prospective cleantech investors might see it as a signal that they’re not welcome.

The bill is also out of step with what most Floridians want, Knecht said. According to a recent survey from Florida Atlantic University, 90 percent of the state’s residents accept that climate change is happening. “When you talk to the citizens of Florida, the majority of them recognize that the climate is changing and want something to be done above and beyond just trying to build our way out of it.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Florida is about to erase climate change from most of its laws on Mar 25, 2024.

This story was originally published by Capital and Main.

Driving on Interstate 215 south of Salt Lake City in late January, I couldn’t help but notice the bumper stickers on the pickup truck in front of me. One featured a rattlesnake and the classic motto “Don’t tread on me,” which dates to the Revolutionary War but has been co-opted by many right-wing ideologues. And the other featured a map of a shrinking lake and the words “Keep the Salt Lake Great,” the motto of a local environmental group focused on protecting Utah’s rivers and ecosystems.

Those dual views perfectly capture the ethos of Utah, a deep red state whose natural beauty is being threatened by more intense heat waves and extreme drought. A proud coal- and oil-producing state, it’s led by conservative lawmakers, and recent national surveys show it’s one of the most Republican states in the country. Back in 2010, the Utah Legislature even passed a resolution that essentially wrote climate change denial into state policy by urging the EPA to “cease its carbon dioxide reduction policies, programs, and regulations until climate data and global warming science are substantiated.”

But since then, Utah has been impacted by climate change more than most states — over the last 50 years, temperatures in the state have risen at about twice the global average, and it has faced worsening drought, wildfires, flash floods and extreme heat waves. The impact has been devastating on the health and well-being of residents, with decreasing productivity of farms and higher rates of respiratory disease and asthma, along with other heat-related diseases.

And climate change has seriously damaged one of the state’s natural wonders — that map on the truck driver’s bumper sticker reveals how climate change has shrunk the Great Salt Lake’s footprint by half in the last decades due to the reduced flow of mountain streams that feed the lake and higher demand for freshwater for new development and agriculture.

The crisis has also increased climate awareness in the state, with half of residents in a recent survey saying that climate change is an extremely or very serious problem and 64 percent saying they’ve noticed significant effects from climate change over the past 10 years.

“For voters, climate has become a bigger issue than it has been in the past,” said Josh Kraft, government and corporate relations manager for Utah Clean Energy, a public interest group that launched a historic compact in 2020 that brought together more than 100 of the state’s political and business leaders to stimulate support for clean energy and energize conversations on climate action and clean air solutions.

That bipartisan concern with climate change is now impacting politics in the state — where two self-professed climate candidates are running to replace Mitt Romney in the U.S. Senate. In total, there are five GOP candidates polling higher than 3 percent and three Democratic candidates running in the June 25 primary.

In the Republican primary, the frontrunner, U.S. Rep. John Curtis, is highlighting the need to address the climate crisis, pushing for more support for clean energy. He founded and leads the Conservative Climate Caucus in Congress and blames his party for not taking climate change seriously.

“We want to work together as Republicans and Democrats, because at the end of the day, we all care about leaving the Earth better than we found it,” Curtis recently told the Sierra Club. “That’s how I talk about it — who doesn’t want to leave the Earth better than we found it?”

But climate activists are doubtful, claiming that Curtis is too reliant on industry-friendly solutions such as carbon capture and opposes some of President Biden’s signature climate accomplishments, including the Inflation Reduction Act.

In the Democratic primary, mountaineer and environmental activist Caroline Gleich has made climate action and air quality a key focus of her campaign. She rallied lawmakers in the state to take action to increase water flow to the Great Salt Lake as part of a larger climate agenda that includes cutting subsidies for fossil fuels, taking advantage of Inflation Reduction Act funds aimed at increasing the use of renewable energy in the state, and protecting public lands. “Our mountains, our air, our rivers and lakes, our lives deserve respect,” Gleich has repeatedly said.

Yet she sees a disconnect between public support for climate action and the policies pursued by the state’s political leadership, noting that the Legislature recently voted to increase the tax on EV charging and to reduce the tax on gasoline. “And when you look at who’s funding these candidates, you see there’s a huge amount of oil and gas and fossil fuel companies giving money to them,” Gleich said.

Indeed, Curtis is a major recipient — his district includes an area known as Carbon County due to its abundance of coal and natural gas, and he has accepted $265,000 from oil and gas industry-linked political action committees since 2017. Curtis did not return calls from Capital & Main for comment.

Gleich’s view is echoed by Zach Frankel of the Utah Rivers Council, an environmental group that distributes the Great Salt Lake bumper stickers. “We’re in a state of climate change denial — politicians might say that it’s real in an election year, but if we start asking them if we should embrace climate adaptive policies, they say no. They assume that any crisis is decades away.”

Frankel is encouraged by the growing public concern over climate issues, such as the shrinking Great Salt Lake — the largest remaining wetland ecosystem in the American West — and the growing frustration with the lack of action.

“The state of Utah has refused to embrace any kind of meaningful policy plan to raise lake levels,” he said, predicting that “it will have to get worse before it gets better.”

As elsewhere in the country, younger voters in the state seem to be more galvanized than older voters about the issue and demanding action. At a climate strike on the steps of the Utah state house last year, activists condemned the Legislature for not making serious efforts to reduce emissions. A legislator’s move to slash emissions at U.S. Magnesium, which harvests lithium and magnesium from the Great Salt Lake, was scaled back to a mere study of the effects of pollutants created in the process.

“Young people are disproportionately affected by eco-anxiety because it’s their future,” said Gleich, who at 38 is the youngest candidate in the Senate race. “That is what is on the line in this election.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline In Utah, climate concerns are now motivating candidates on Mar 24, 2024.

California’s Yurok Tribe had 90 percent of its territory stolen during the mid-1800s gold rush. Now, it will be getting a piece of its land back that serves as a gateway to Redwood state and national parks.

For decades, the ancient redwoods on former Yurok lands were decimated for lumber and a sawmill built to process it. Now, in a first-of-its-kind agreement between the Yurok, the National Park Service, California State Parks and nonprofit Save the Redwoods League, the Tribe will become the first to manage Tribal land alongside the National Park Service, a press release from Save the Redwoods League said.

The historic memorandum “starts the process of changing the narrative about how, by whom and for whom we steward natural lands,” said Sam Hodder, Save the Redwoods League president and CEO, in a statement, as The Guardian reported.

Rosie Clayburn, the Yurok’s cultural resources director, said getting back the 125 acres of land — called ‘O Rew in their native language — shows the “sheer will and perseverance of the Yurok people. We kind of don’t give up,” as reported by The Guardian.

Traditionally, the Tribe only used fallen trees to build their canoes and houses.

“This is work that we’ve always done, and continued to fight for, but I feel like the rest of [the] world is catching up right now and starting to see that Native people know how to manage this land the best,” Clayburn said.

In 2013, Save the Redwoods League bought the property and started working with the Tribe to restore it.

“Even after the mill closed, its aging structures and acres of asphalt marred a crucial redwoods ecosystem near the confluence of Prairie Creek and Redwood Creek. The degraded site was a painful reminder of the area’s complex history of cultural devastation, ecological destruction, and economic hardship, in the heart of traditional Yurok land,” the press release said. “Save the Redwoods League saw this scar on the landscape and recognized an incredible opportunity for healing and renewal.”

The vision of the transfer and restoration of the land is to revive the ecosystem and create an entrance to the Redwood National and State Parks that includes a traditional Yurok village, exhibits and hiking trails, Save the Redwoods League said.

“This transformation will be part of our ongoing efforts to create a world-class recreational gateway where the Yurok Tribe can welcome the public to explore the majesty of the redwood forest and their ancestral lands through the lens of conservation, revitalization, and living Indigenous culture,” the press release said.

In 2021, the team of collaborators began the $23 million Prairie Creek restoration. Asphalt equivalent to 10 football fields was removed by Indigenous crews during the first three years. A section of the creek that had been heavily degraded was restored, beginning the revitalization of steelhead, salmon and wildlife habitat.

To achieve the 2026 conveyance target, agreements and mechanisms for co-management, permanent conservation, funding and public access must be finalized.

“As the original stewards of this land, we look forward to working together with the Redwood national and state parks to manage it,” Clayburn said, as The Guardian reported.

The post California’s Yurok Tribe Becomes First to Steward Land Alongside National Park Service appeared first on EcoWatch.

This story was originally published by Capital B.

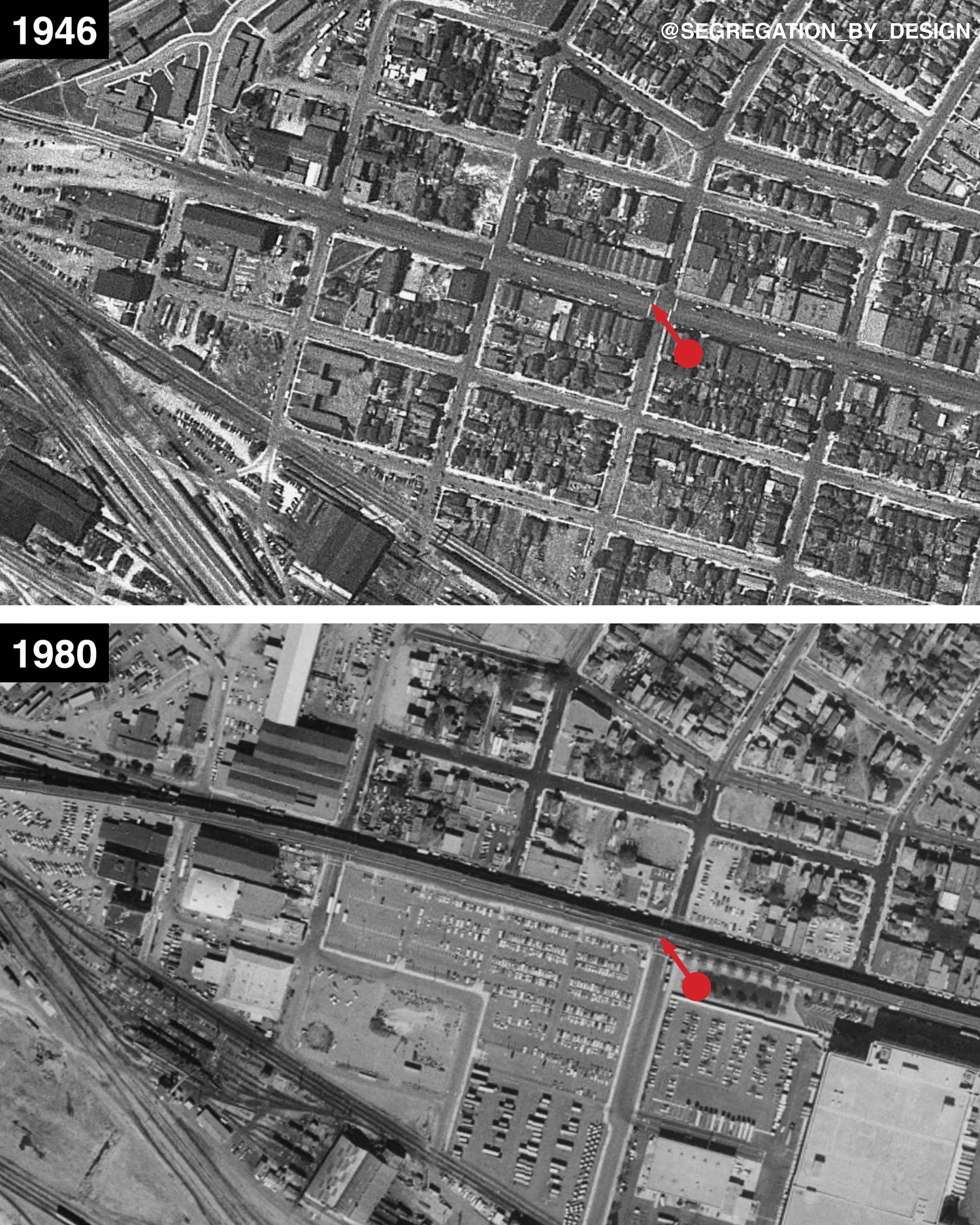

Nearly 45 years ago, the Acres Homes area north of Houston was the largest unincorporated Black community in the South, a thriving 9-square mile area where homeownership was the norm. That was until the city of Houston annexed it, and the Interstate 45 highway was built through its heart.

In the aftermath, the community’s poverty rate has jumped to almost double the city’s average, and health ailments from pollution have increased.

President Joe Biden’s bipartisan infrastructure law, one of the nation’s most significant investments in curbing climate change, was supposed to consider the history of areas like Acres Homes in an attempt to make communities whole again.

By creating a pathway to building the clean energy economy, from expanding electric school bus fleets to subways and mass transit options, it would also serve as a way to reverse the well-documented history of how the country’s highways ripped apart Black communities. As residents were displaced, homeownership chances were stunted, and Black people were left overexposed to pollution from cars and trucks and became most likely to die in car crashes.

Instead, the law is actually increasing pollution and contributing to the continued disruption and displacement of Black communities, according to a new report by the climate policy group Transportation for America.

According to the new report, what has primarily happened is a repeat of that history: freeways, highways, and more roads. Out of the more than 55,000 projects totaling roughly $130 billion implemented through the $1.2 trillion spending package, nearly half of the spending has been allocated to highway expansion.

However, less than three weeks following the report’s release, the Biden administration announced a $3.3 billion spending plan to “reconnect and rebuild communities” in more than 40 states disconnected by highways throughout the 20th century. Some of the spending’s most prominent focuses include Milwaukee, Atlanta, and Los Angeles, where public transit options will increase and some highways will be capped.

Still, the spending pales in comparison to recent allocations to expand freeways.

Last year, the Biden administration supported a nearly $10 billion expansion of that same highway that tore through Acres Homes. The expansion led to the demolition of almost 1,000 homes in a majority Black and Latino community.

It’s a mistake we’ve seen time and time again in this country, said Cherrelle J. Duncan, director of community engagement at LINK Houston, a policy organization focused on improving transit options in Houston’s Black and brown communities.

“Highways and expanding them don’t make your communities easier or lessen traffic. It doesn’t make your cars move faster,” she explained. “All it does is increase our air pollution, our noise pollution, and it also just terribly affects Black communities and brown communities by pulling resources, and also making them quite literally bypass and drive right past our communities.”

A study by Air Alliance Houston, a nonprofit environmental justice group, found that levels of benzene, a carcinogen, will more than double at some schools along the expanded highway.

Nationwide, the highway investment will practically wipe out any positive climate benefits from other spending priorities. The simple result, the report found, is that the U.S. will generate more emissions from transportation, already its largest source of planet-heating gases, than if the bill hadn’t ever passed. By 2040, the pollution created from these projects will be equivalent to running 48 coal-fired power plants a year.

The spending so far has created a “climate time bomb” that will also perpetuate the displacement of Black communities, the report concluded.

It is even known to exacerbate climate concerns, like in Elba, Alabama, where Capital B reported on how a new highway expansion intensified a flooding crisis in a rural Black community, leading to fears that residents would be flooded out of their homes and displaced.

Last month, a coalition of 200 climate organizations called for a national moratorium on highway expansions, particularly due to the harm they’ve caused in Black and brown communities.

“We’re seeing how infrastructure literally tears us apart,” Duncan said. “We’ve created a division between communities so that we’re no longer able to interact with each other while making it harder to build climate resilience, to stop floods, or flee in times of disaster.”

While the Department of Transportation under the Biden administration recommended that states prioritize repairing roads over expanding them and urged states to consider the impact on communities of color reeling from decades of division by highways, the spending bill granted states considerable discretion in allocating funds.

As with many of Biden’s policies, it prompted a backlash from Republicans in Congress and was mostly overlooked by states such as Texas and even California, which received the most funds through the spending bill. At the same time, there has been little interest in improving access to public transit, which has taken a hit nationwide after the pandemic lowered commuter revenue.

In Houston, Duncan has seen firsthand how the country’s renewed investment in highways over other transit options is disrupting a new generation of Black children.

“If you have car-centric infrastructure,” Duncan said, “you’re simply going to have significantly worse air pollution, going to have more car crashes, and it’s all going to be centered in Black communities.”

As Capital B reported last year, Black people are almost twice as likely as white people to die in car crashes.

There have been attempts nationwide to reconnect Black communities disrupted by freeways. In Detroit, for example, where a vibrant Black community was destroyed for a highway in the 1950s, there is a plan to eliminate the highway. The Biden administration has allocated $105 million to the project.

However, the plan is to replace the highway with a street that is six lanes wide and divided by a median for most of its length. Transit advocates say the current design is still too focused on the concerns of drivers.

This pathway of “boulevardization” in communities disturbed by highways has been the main tactic implemented by cities across the country. This approach involves removing highway structures entirely and replacing them with urban boulevards, but as in the case of Detroit, it can still prioritize cars rather than city residents. In some cases, it has even led to gentrifying and displacing the very communities it aims to support.

One of the earliest examples of boulevardization, which took place in Oakland, California, in the early 1990s and has been used as a prime example of the process’s success, actually led to the neighborhood’s Black population dropping by a third as the median household income increased by 55 percent between 1990 and 2010.

It’s a perfect example of intention never being actualized because Black communities aren’t being listened to, Duncan said.

“It’s critically important for every agency and city organization to involve diverse voices when it comes to planning transportation,” Duncan said. “If you are going to actively rip apart our communities and actively separate them by highways, the least that you can do is truly listen and engage them to ensure that these project fixes and policies don’t overlook us again.”

Over the past year, Duncan’s organization has worked to collect community input for similar highway removal attempts and calls for investment in walkability and public transit; she hopes leaders will listen.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How Biden’s infrastructure plan created a ‘climate time bomb’ in Black neighborhoods on Mar 23, 2024.

After a plant suffers an injury, metabolites called terpenoids are released to enhance its defenses. A new study led by scientists from Tokyo University of Science (TUS) has found that rose essential oil (REO) has the ability to stimulate defense genes in the leaves of tomato plants.

REO also attracts herbivore predators that protect plants from moths and mites. Because of these effects, the researchers concluded that REO can be effective as a sustainable organic pesticide.

“[O]ur study showed that rose essential oil (REO), rich in β-citronellol, played a crucial role in activating defense genes in tomato leaves. As a result, leaf damage caused by herbivores, such as Spodoptera litura and Tetranychus urticae, was significantly reduced,” the researchers wrote in the study. “Our findings suggest a practical approach to promote organic tomato production that encourages environmentally friendly and sustainable practices.”

Essential oils (EOs) derived from plants are used in cosmetics, detergents, food additives and pharmacology, a press release from TUS said.

The bioactivities of EOs have been shown to be exceptionally safe and to benefit human health. In addition, they have been found to induce neurotoxic effects in insects, causing a repellent response.

Plant EOs have an abundance of terpenoids that are able to control defense responses in plants by regulating the expression of their defense genes. When komatsuna and soybean plants are grown near mint, they show a marked improvement in their defense properties that make them resistant to herbivores. This happens through “eavesdropping” — a process during which the mint plant releases volatile compounds that trigger defense genes.

“Today, applying chemical pesticides is the method of choice for crop protection, but the damage they cause to the environment and ecosystems, along with the need to increase food productivity, stresses the need for safer alternatives,” the press release said. “Thus, there is an urgent need for investigation of plant defense potentiators. In this regard, the availability of EOs makes them attractive candidates as environmentally friendly plant defense activators.”

The lack of enough proven EOs to meet demand presents a challenge, however. To address this issue, the research team looked at tomato defense responses activated by 11 EOs.

“EOs used as fragrances for various purposes contain odor components, which may have the ability to work like volatile compounds in conferring pest resistance. We aimed to investigate the effects of these EOs on plants’ insect pest resistance,” said professor Gen-ichiro Arimura of the TUS Department of Biological Science and Technology in the press release.

The research team profiled how EOs enriched with terpenoid affected tomato plants. They applied solutions diluted with ethanol from 11 distinct EOs to potted tomato plant soil. After studying the leaf tissue’s gene expression through molecular analyses, they found that REO boosted the levels of plant defense genes PIR1 and PIN2.

The tomatoes treated with REO also showed less leaf damage from Spodoptera litura moth larvae and Tetranychus urticae mites.

The team also measured REO activity in a field experiment. They found 45.5 percent less damage from tomato pests than the control. The researchers feel REO could act as an effective pesticide alternative during winter and spring when there is less severe pest infestation. In addition, they think it could potentially lower pesticide use by nearly 50 percent during the summer.

“REO is rich in β-citronellol, a recognized insect repellent, which enhances REO’s efficacy. Owing to this, damage caused by the moth larvae and mites was significantly minimized, confirming REO as an effective biostimulant. The findings also showed that a low concentration of REO did not repel T. urticae but attracted Phytoseiulus persimilis, a predator of these spider mites, thus exhibiting a dual function of REO,” Arimura explained in the press release.

The study, “Novel Potential of Rose Essential Oil as a Powerful Plant Defense Potentiator,” was published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry.

The study demonstrated the capacity of EO enriched with β-citronellol in turning on the defense genes of tomato leaves. It also showed that REO effectively enhances plant defense in a safe manner that does not leave toxic residue or result in phytotoxicity.

“Our study suggests a practical approach to promoting organic tomato production that encourages environmentally friendly and sustainable practices. This research may open doors for new organic farming systems. The dawn of potent environmentally friendly and natural pesticides is upon us,” Arimura said.

The post Rose Essential Oil Is a Safe and Effective Pesticide for Organic Agriculture, Study Finds appeared first on EcoWatch.

Wisconsin has passed two bills allowing for the development of a statewide charging network. The bipartisan bills, Wisconsin Acts 121 and 122 (2023), were signed into law by Governor Tony Evers on March 20.

As reported by Wisconsin State Journal, the laws allow the state to utilize about $78 million of federal funding from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law’s National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) program. The funding will go toward increasing the number of charging stations along major state highways and interstates.

“We don’t have to choose between protecting our environment and natural resources or creating good-paying jobs and infrastructure to meet the needs of a 21st-Century economy — in Wisconsin, we’re doing both,” Evers said in a press release. “Expanding EV charging infrastructure is a critical part of our work to ensure Wisconsin is ready to compete and build the future we want for our kids — one that is cleaner, more sustainable, and more efficient. Thanks to President Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, we’re ready to get to work.”

The federal funding goes toward Level 3 chargers, or fast-chargers, that can recharge EVs in an hour or less, the Associated Press reported. While the federal government recommends that charging stations along Alternate Fuel Corridors (AFCs) be placed no more than 50 miles apart, the secretary of the Wisconsin Department of Transportation, Craig Thompson, noted that the expanded state EV charging network will be spaced apart by 25 miles or less to better support the increased demand for electric vehicles.

“WisDOT is ready to activate the federal funding and help industry quickly build fast chargers across the state,” Thompson said. “Electric vehicle drivers in Wisconsin will soon be able to travel about 85 percent of our state highway system and never be more than 25 miles away from a charger.”

Act 121 allows businesses, like gas stations or other businesses along the charging network, to sell electricity for charging by kilowatt hours rather than the amount of time charged, creating more incentive for businesses to join the network. The former law required businesses that had EV charging stations to be regulated like a public utility company, the Wisconsin State Journal reported.

The state will charge an excise tax of $0.03 per kilowatt hour of electricity sold at all new charging stations and any existing level 3 charging stations. Existing level 1 and level 2 charging stations will not be charged the excise tax, and the excise tax does not apply to residential level 3 chargers, according to the bill.

As the Associated Press reported, the state currently has around 580 chargers available to the public, and the newly signed bills will support the addition of 65 fast-charging stations.

The post Wisconsin to Expand Statewide EV Charging Network appeared first on EcoWatch.

At 11 a.m. on the last Wednesday of February, Denver opened the first application window of the year for its e-bike rebate program, which offers residents upfront rebates of $300 to $1,400 for a battery-powered bicycle. Within three minutes, all of the vouchers for low and moderate income applicants had been claimed. By 11:08 a.m., the rebates for everyone else were gone too, and the portal closed.

Even in its third year, Denver’s ambitious campaign to get residents to swap some of their driving for riding remains as popular as ever. “It’s exciting that people are really interested in this technology,” Mike Salisbury, the city’s transportation energy lead, told Grist. “Every trip we can convert to an e-bike will be a big climate win.”

Transportation is among the biggest sources, if not the biggest source, of a city’s carbon emissions. To cut that footprint, officials often turn to costly, intensive transit projects and building out electric vehicle infrastructure. Denver is doing those things, but also propping up smaller forms of mobility. It spent more than $7.5 million in just two years on e-bike vouchers, supporting the purchase of nearly 8,000 of the battery-powered bicycles, which can zip along at up to 28 mph, power up hills, and carry passengers or cargo.

“We’re just very bullish on e-bikes,” said Salisbury. “They have this huge potential to replace vehicle trips.”

The vouchers are saving some 170,000 miles in car trips per week and around 3,300 metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions annually, according to the city. Its Office of Climate Action, Sustainability, and Resiliency calls it “one of the most effective climate strategies that the city and county of Denver has deployed to date.”

There are about 160 of these incentive programs across the U.S. and Canada, and while Denver wasn’t the first to implement one, the size and success of its undertaking has attracted the attention of other governments and utilities. Congress is taking note as well: California Representative Jimmy Panetta reintroduced the federal Electric Bicycle Incentive Kickstart for the Environment Act, or E-BIKE Act, which would offer a 30 percent federal tax credit for e-bike purchases, last year.

Funded through a voter-approved $40 million Climate Protection Fund, which directs a portion of the city’s sales tax toward decarbonization initiatives, the program offers income-based rebates that can be redeemed at designated bike shops. Providing the discount at the register helps those who might otherwise be unable to afford the upfront cost, which typically begins around $1,200 and can reach several thousand dollars.

Residents making less than 60 percent of the area median income of around $52,000 can get $1,200 for a standard e-bike and $1,400 for a cargo model (useful for carrying gear, making deliveries, or hauling kids). Moderate-income recipients receive between $700 or $900, and everyone else can get $300 or $500. Online applications open several times each year and vouchers are offered on a first-come, first-served basis.

The goal is to reduce emissions from the transportation sector, Denver’s second-largest contributor of greenhouse gases, by targeting short vehicle trips. According to Salisbury, 44 percent of residents’ trips are under 5 miles and most are under 10, feasible distances to travel on an e-bike.

“E-bikes aren’t going to replace every single trip for every single person,” he said. “But there’s this huge potential to replace, especially in an urban environment, shorter distance trips that someone is making by themselves. Or they can use an e-cargo bike to take their kids to school.”

That’s one of the many ways Jeff Gonzales, a marketing professional and father living near the University of Denver, uses the power-assisted bike that he bought two years ago with the help of a voucher.

At the time, Gonzales drove a customized Toyota Tacoma pickup. “It was awesome, but it was a gas guzzler,” he told Grist. Gas was so expensive that he and his wife were trying to minimize their driving as much as possible. But their two toddlers were getting too heavy to tow with the family’s bike trailer, affectionately called “the chariot.” When an employee at his local bike shop mentioned the rebates for power-assisted bicycles, he decided to take one for a test ride.

“I was like, ‘This is pretty cool,’ and then I asked them, ‘Can I hook the chariot behind it?’ They said ‘Absolutely.’” Gonzales sold his truck, applied for a voucher, and bought the bike. He began riding it to the grocery store, taking the kids to school, and even making the 24-mile round-trip commute to his office twice a week.

“That first summer we had it, I think there were times that we didn’t get in the car for about two weeks at a time,” he said.

In a 2023 survey of voucher recipients, 43 percent of respondents cited commuting as their primary reason for getting an e-bike, and 84 percent said the machines replaced at least one vehicle trip per week. The city estimates that recipients are eliminating a weekly average of 21 miles in their cars.

Commuting on two wheels often allows riders to avoid traffic or take more direct routes than those offered by public transit. “People are sharing feedback with us on how it’s enabled them to get to their job much faster, easier, at a much lower cost, without having to make two or three transit transfers to get to a place,” said Salisbury.

Gonzales said he often finds biking to work quicker, but even when the ride doesn’t save time, it’s more enjoyable. “It sucks to sit in traffic,” he said. “I’d rather be moving on a bike, and if I get tired, I can increase the power level, but I’m still moving.”

The clean energy nonprofit Rocky Mountain Institute, or RMI, found that if the country’s 10 most populous cities shifted a quarter of all short vehicle trips to e-bike rides, they could save 4.2 million barrels of oil and 1.8 million metric tons of CO2 in one year. That’s the equivalent of taking four natural gas plants offline. As an added bonus, those riders also would save a combined total of $91 million per month in avoided fuel and vehicle maintenance costs, according to RMI.

But a recent study from Valdosta State University and Portland State University questions the cost effectiveness of achieving greenhouse gas emissions this way. “Even when e-bike incentive programs are designed cost-effectively,” the authors concluded, “the costs per ton of CO2 reduced still far exceed those of alternatives or reasonable social costs of GHG emissions.” A rebate program can still be beneficial, the study concludes, but may need to be justified through its additional benefits, like promoting exercise and relieving traffic congestion.

Salisbury said the report’s critique overlooks how cities must tackle emissions in multiple ways. “There are lots of other things the city is working on, like building bus rapid transit and other infrastructure, but those take a long time,” he said. “If we want to see reductions as soon as possible, we need to look at programs that can contribute to that right away.”

He also pointed out that increasing access to e-bikes takes specific aim at one of the city’s most difficult sectors to decarbonize. “Yes, it’s cheaper to invest in a solar array, but that’s not going to do anything for transportation emissions.”

That’s not to say that getting residents to swap four wheels for two is as simple as doling out a voucher. E-bikes require infrastructure, including bike lanes that can accommodate both motorized and analog riders, as well as places to charge and safely store bikes.

In the past five years, the city has added 137 miles of “high-comfort” bike lanes. Last month, it launched the Denver Mobility Incentive Program, offering grants to nonprofits and other organizations to install bike storage lockers, places to plug in, and even set up e-bike libraries where residents can borrow rides for free.

“It’s all part of an ecosystem,” said Salisbury. “Dropping 8,000 e-bikes on the road would be much less effective if we didn’t have that co-developed infrastructure.”

Gonzales uses that infrastructure when he has to cut through busy downtown Denver to reach his office. “About 90 percent of the time I’m on protected bike lanes,” he said. “It makes me feel a lot more comfortable about biking 12 miles across town.”

The city has also had to grapple with how to ensure that all residents can access the program. While more than 44 percent of the vouchers have gone to low-income applicants, the first-come, first-served application process has been criticized for favoring people with the time and computer access to log on as soon as the portal opens. And so far, the racial demographics of the recipients has not proven reflective of the city’s population. In 2023, only 8 percent of survey respondents were Latino and 3 percent were Black, while Denver’s population is 29 percent Latino and almost 9 percent Black. Despite offering up to $1,400 for adaptive bikes, the program has only distributed about 20 so far.

In response, Denver has worked with community-based organizations to funnel rebates directly to people who might not know about or be able to apply for them. It plans to distribute 600 vouchers through such groups this year.

The people least able to access the program may also be the ones who would put it to the most use. Survey results have indicated that applicants who received vouchers through community organizations are replacing 80 percent more vehicle miles than standard-voucher recipients.

This also marks the first year that Denver will offer a specific rebate amount for moderate-income applicants, an attempt to address the “missing middle” of people who earn closer to the city’s median income but need a bit more help to afford a ride.

What the city will continue to struggle with this year is a demand for all levels of vouchers that far exceeds supply. The next round of applications will open on April 30.

One of those applications might come from the Gonzales family. With a third baby now in tow, they’re thinking of getting a second power-assisted bike to transport the whole family. “When the little man gets bigger, we’d probably get another,” said Gonzales, especially if the city is still offering vouchers. “They’re not the cheapest things in the world, so the rebate program certainly helps.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline In Denver, e-bike vouchers run out as fast as Taylor Swift tickets on Mar 22, 2024.

This story was produced in partnership with Atlanta News First.

Thousands of warehouse workers across the U.S. are likely regularly exposed to the cancer-linked chemical ethylene oxide. More than half of the country’s medical equipment is sterilized with the compound, which the EPA considers a carcinogen. Ethylene oxide evaporates off the surface of these medical products after they’ve been sterilized, creating potentially dangerous concentrations of air pollution in the buildings where they’re stored.

By and large, the EPA does not regulate these buildings — in fact, regulators don’t even know where most of them are. The Office of Safety and Health Administration, the federal agency in charge of worker protection that is known by its acronym, OSHA, has also done relatively little to evaluate worker exposure in these warehouses. But last week, OSHA opened a new investigation into a Georgia warehouse that stores medical devices sterilized with ethylene oxide, raising questions about whether the federal government is beginning to respond more quickly to these risks.

On March 13, the U.S. Marshals Service and the Douglas County sheriff’s office assisted OSHA in executing a search warrant at a warehouse leased by the medical device company ConMed in Lithia Springs, 17 miles west of Atlanta. The surprise inspection was initiated almost two weeks after a Grist and Atlanta News First investigation revealed that workers employed by ConMed had been unknowingly exposed to the chemical. Ambulances were routinely called to the facility as workers convulsed from seizures, lost consciousness, and had trouble breathing.

The workers sued the company in 2020, but the lawsuit was ultimately dropped earlier this year after a judge dismissed some of their claims, citing state labor laws. (Under Georgia law, once employees seek workers’ compensation from the state, they are barred from suing employers separately.) ConMed denies the lawsuit’s allegations that it knowingly exposed workers to ethylene oxide and maintains that no individual medical emergency can be tied to exposure to the chemical. A company representative told Grist that it is “committed to fully complying” with all applicable regulations and conducts monthly ethylene oxide testing for its employees to review.

“Given our many years of full cooperation with OSHA, as well as the fact that OSHA has inspected our Lithia Springs facility five times since 2019, ConMed was surprised by the manner in which OSHA elected to inspect the facility on March 13,” a company representative told Grist in an email.

Ethylene oxide is a powerful fumigant, but it poses significant health risks and is linked to lung and breast cancers as well as diseases of the nervous system. Once medical devices are treated with ethylene oxide, the chemical continues to evaporate off the surface of the product as it moves through the supply chain. While the devices are trucked to warehouses, stored, and then shipped to hospitals, the products continue to quietly off-gas ethylene oxide, putting workers who come into contact with it at risk.

In a new rule it published last week, the EPA said that it will begin regulating toxic emissions from warehouses located on the same site as the sterilizer plants that actually apply the chemical. However, the agency argued that constraints stemming from the regulatory definition of the sterilization industry mean that offsite warehouses will be excluded from oversight. Even if the agency could clear that bureaucratic hurdle, it does not have “sufficient information to understand where these warehouses are located, who owns them, how they are operated, or what level of emissions potential they may have,” in the agency’s words.

What little the EPA knows about the threat from offsite warehouses was gleaned from a study conducted by state regulators in Georgia. That effort initially identified seven off-site warehouses and found that at least one of the state’s warehouses was emitting more ethylene oxide than the sterilization plant that first treats the medical products before sending them out for storage. Federal officials will begin gathering data on warehouses, according to the new EPA rule, and use it to determine whether a completely new regulation governing storage facilities should be developed. Such a process could take years, according to experts who spoke to Grist. All the while, warehouse workers across the country will continue to inhale ethylene oxide, in many cases without their knowledge.

“Up until eight years ago, a lot of people had no idea that the sterilizer facility, which looks like your regular office park facility, was poisoning them,” said Marvin Brown, an attorney with the environmental nonprofit Earthjustice. “Now we have this additional issue of these warehouses that are continuing to poison people, and most people have no idea that they live next to one or work at one.”

Brown and other experts Grist spoke to said the agency could take one of two approaches to regulating warehouses. It could expand the definition of regulated facilities under the sterilizer rule it finalized earlier this month, or it could create a new category of facilities that covers warehouses and develop a separate rule. Both come with challenges.

Reopening a new rule that has already been finalized is tricky, according to Scott Throwe, a former EPA enforcement official who worked on a number of rules that the EPA rolled out in the decade after amendments to the Clean Air Act were passed in 1990. “It’s a huge can of worms,” he said. “Once you open a rule, then you have to fix this and you have to fix this. It snowballs.”

Alternatively, the EPA could draft a new rule entirely, he added, but the agency is unlikely to do that either, because of the sheer amount of effort such a process would take. Throwe said that the EPA’s decision not to include offsite warehouse regulations in its new rule means that the agency doesn’t have either the time, the resources, or the will to tackle those emissions at this time.

“They’re going to declare victory on this one and move on,” he said. “They ain’t reopening that rule unless someone sues them.”

A spokesperson for the EPA said that the agency has an “incomplete list” of warehouses and that it has not conducted any risk assessments of them. As a next step, the agency expects to follow up with sterilization companies that did not provide detailed information about the location of their warehouses in response to a 2021 request. Once those responses are received, the agency plans to conduct emissions testing at some of the warehouses. If the agency decides to pursue a separate rule for warehouses, that process could take four to five years, the spokesperson said.

The rule governing medical sterilization facilities was one of the first industry-specific air quality regulations that the EPA ever crafted. In its amendments to the Clean Air Act in 1990, Congress published a list of 189 toxic air pollutants and asked the agency to develop regulations for each industry emitting at least one of them. Officials published the first standards for medical sterilizers in 1994 with little fanfare, according to Throwe. At the time, regulators and toxicologists were unaware of the true risks of ethylene oxide, which was used to fumigate a range of materials, from books to spices to cosmetics. With the new law giving the agency just a decade to craft dozens of new regulations, officials rushed the process, sacrificing the efficacy of some standards along the way.

“It was like drinking from a firehose,” Throwe said. “Unrealistic statutory deadlines became court-ordered deadlines.”

Drafting new regulations for a polluting industry, regulators quickly learned, was a lot of work. In addition to collecting and analyzing copious amounts of data on a particular type of plant’s emissions and configuration, officials had to consult engineering experts to understand what kinds of technologies they could ask companies to use to control their emissions. Decades later, the process for revising these regulations to better protect exposed communities is no different. It took the EPA almost a decade to publish its new sterilizer regulations, and it did so under a court-ordered due date after missing a previous deadline to update the rule. If the agency were to issue a new rule for warehouses, the time and resource commitment would be steep, Throwe said.

While the EPA is not responsible for worker safety, it has found a roundabout way to increase protections for those coming in close contact with ethylene oxide. Since ethylene oxide is a fumigant, the agency is also pursuing separate oversight under a federal pesticide law. The Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act requires the agency to evaluate pesticides every 15 years and determine where, how, and how much of a given pesticide may be used. In April, the EPA proposed a new set of requirements including reducing the amount of ethylene oxide used for sterilization and mandating that workers wear protective equipment while engaging in tasks where there is a high risk of exposure to the chemical. Since the law applies to all facilities where ethylene oxide is used — not just sterilization plants — warehouse workers could benefit from the requirements once it is finalized.

Some state and local agencies are proactively regulating warehouses themselves. After the Georgia Environmental Protection Division found that one warehouse was estimated to emit about nine times as much ethylene oxide as the facility that sterilized it, the agency began trying to find similarly dangerous warehouses. After scouring the internet and reaching out to companies, the agency identified four warehouses that were emitting more ethylene oxide than permitted under state law. The agency is now in the process of issuing permits and requiring controls for those facilities.

In Southern California, which has a large concentration of sterilization facilities, the local air quality regulator has included requirements for offsite warehouses in a rule that primarily targets sterilization plants. The rule categorizes warehouses into two tiers — those with an indoor space of 250,000 square feet or more and those with between 100,000 and 250,000 square feet. Depending on the size of the facility, the warehouses are subject to different reporting and monitoring requirements. In the course of developing the rule, the agency identified 28 warehouses that fall into one of these two tiers. The agency finalized the rule in December, and larger warehouses will be studied for a year to determine whether they emit significant amounts of ethylene oxide.

Editor’s note: Earthjustice is an advertiser with Grist. Advertisers have no role in Grist’s editorial decisions.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline A loophole in the EPA’s new sterilizer rule leaves warehouse workers vulnerable on Mar 22, 2024.

If you were to create a recipe for plastics, you’d need a very big cookbook. In addition to fossil fuel-based building blocks like ethylene and propylene, this ubiquitous material is made from a dizzying amalgam of more than 16,000 chemicals — colorants, flame retardants, stabilizers, lubricants, plasticizers, and other substances, many of whose exact functions, structures, and toxicity are poorly understood.

What is known presents many reasons for concern. Scientists know, for example, that at least 3,200 plastic chemicals pose risks to human health or the environment. They know that most of these compounds can leach into food and beverages, and that they cost the U.S. more than $900 billion in health expenses annually. Yet only 6 percent of plastic chemicals — which can account for up to 70 percent of a product’s weight — are subject to international regulations.

Over the past few months, a flurry of studies and reports have highlighted one group of substances as particularly problematic: “endocrine-disrupting chemicals,” or EDCs. These chemicals, released at every stage of the plastic life cycle, mimic hormones and interfere with the metabolic and reproductive systems. They were recently found in samples of plastic food packaging from around the world, and a study published last month linked them to 20 percent the United States’ preterm births.

The unchecked production, distribution, and disposal of plastics and other petrochemical-based products has led to “a perpetual cycle of human exposure to EDCs from contaminated air, food, drinking water, and soil,” Tracey Woodruff, a professor of reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Francisco, wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine earlier this month. Philip Landrigan, a public health physician and professor of epidemiology at Boston College, told Grist that the crisis has “quietly and insidiously gotten worse while all attention has been focused on the climate.”

Although some policymakers have taken steps to protect people from EDCs — the European Commission, for example, in 2022 proposed stricter labeling regulations that would require companies to alert consumers of their hazards — many in the field believe the overarching response has been incommensurate with the scale of the crisis. Because so many plastics and petrochemical products are traded internationally, some endocrinologists and public health authorities believe a global approach is needed.

“This is an international problem that is affecting our world and its future,” said Andrea Gore, a professor of pharmacology and toxicology at the University of Texas, Austin.

Gore and others are appealing to the negotiators of the U.N. global plastics treaty, who meet for their next round of talks next month in Ottawa, Canada. There is increasing interest among delegates for a treaty that not only protects the environment, but public health — a step that the international nature of the EDC problem makes clear must be taken.

The endocrine system is complex, involving a series of glands throughout the body that secrete chemical messengers called hormones. These molecules lock onto a cell’s receptors to induce some kind of response: perhaps the production of another hormone, or the correction of a nutrient imbalance. Endocrine hormones control a long list of necessary human functions like growth, metabolism, reproduction, lactation, and managing blood sugar — any malfunction, let alone absence, of these processes can lead to health problems like infertility, diabetes, hypertension, and death.

EDCs tamper with the endocrine system, often by mimicking hormones to trigger the corresponding response, or by blocking them to prevent it from happening at all. Research has identified at least 1,000 of these substances in pesticides, inks, building materials, cosmetics, and plastic products, but the nonprofit Endocrine Society, whose members include physicians and scientists, calls this “only the tip of the iceberg” due to the enormous number of chemicals yet to be tested.

Some of the most common or familiar EDCs found in plastics include phthalates, used to make the material more flexible; bisphenol A, or BPA, used to make strong, clear products; and PFAS, a class of more than 14,000 chemicals used to make food containers, outdoor clothing, and other products oil- or water-repellent. Other EDCs of concern include organophosphate ethers, benzotriazoles, and PBDEs, all of which are used to make plastic products fire- and light-resistant.

What makes this particularly worrisome is that humans can be exposed to endocrine-disrupting chemicals simply by touching plastic, inhaling microplastics within dust, and eating food or drinking water that has been in contact with plastic. According to one 2022 study, more than 1,000 chemicals — including many EDCs — commonly used in packaging like takeout containers can migrate into food. A separate study from 2021 found that more than 2,000 chemicals can leach from a single plastic product into water.

As noted in a report published last month by the Endocrine Society and the nonprofit International Pollutants Elimination Network, or IPEN, exposure to endocrine-disrupting substances can occur throughout the plastic life cycle. Fracking for oil and gas — the material’s main ingredients — uses more than 750 chemicals, many of which are known or suspected endocrine disruptors, and people living near these operations may have an elevated risk of developmental or reproductive problems. More EDCs are released during plastics manufacturing, sometimes in air and water emissions, other times on the backs of nurdles, tiny plastic pellets that can be shaped into larger products. These pebble-sized pieces often spill directly from factories or during transportation, and can release their chemicals once in the environment.

At the end of the plastic life cycle, incinerators and landfills can release PFAS, dioxins, PCBs, and other endocrine disruptors as air or soil pollution — some of which may contaminate nearby food supplies. Littered plastics tend to make their way into the ocean, where they break down into microplastics and leach some of those same EDCs, along with others like dibutyltin and mercury.

Those facing the greatest risk tend to be residents of low-income communities and people of color. “They’re more likely to be living in areas where there’s more pollution,” Gore said — like from nearby plastics manufacturing facilities or waste disposal sites. Plus, she added, low-income families often live without easy access to fresh produce and are more dependent on foods packaged in plastic. “We know people of lower socioeconomic status have disproportionate exposures.”

Reducing exposure to endocrine disruptors presents a challenge for several reasons. The biggest is the U.S. and other countries’ lax approach to chemical regulation, which doesn’t usually require that new compounds be tested for endocrine-disrupting properties or other safety concerns before they can enter production and get incorporated into products. “Right now we operate on the basis that all chemicals are innocent until proven guilty,” Landrigan told Grist.

Even when scientists agree that something is harmful, bureaucratic delays and industry lobbying often impede regulation. The Toxics Substances Control Act, or TSCA — the United States’ main chemical law — has for example only banned a handful substances in the nearly 50 years since it was passed, a period in which at least 100,000 new chemicals have entered the market, according to Landrigan. This is partly due to the unrealistic expectation that scientists draw a direct, causal link between a substance and specific health effects, which would require unethically exposing people to toxicants and observing the outcomes.

Another unfortunate side effect of that expectation is a phenomenon called “regrettable substitution,” where companies swap chemicals known to be harmful for lookalikes that haven’t been studied as extensively. Later research often reveals the substitute is just as toxic as the original, if not more so. This has occurred on a wide scale with EDCs such as PFAS, as well as bisphenols — although now that several countries have restricted BPA from plastic products like baby bottles, products labeled (often inaccurately) as free from that substance are now being manufactured with bisphenol S, despite research suggesting it also disrupts the endocrine system.

Some scientists accuse the chemical industry of “weaponizing uncertainty” to delay or kill regulation, a strategy they liken to Big Oil’s campaign to raise doubt about the reality of climate change. But for many EDCs in particular, they agree there is strong enough associative evidence of their harms — from cell and animal studies, as well as observations in people who have been exposed to the chemicals at work or as a result of an accident — to warrant bans and restrictions.

Scientists and public health advocates have been trying to reform chemical regulations for years now, but the U.N.’s global plastics treaty presents an opportunity to do so on an international level. “A global treaty can’t reform TSCA,” Landrigan said, “but it can set benchmarks telling countries that if they want to ship their products internationally, they have to conform to certain standards.”

One leading proposal for the treaty is that negotiators create a comprehensive inventory of the many chemicals used in plastic production, along with a list of “chemicals of concern” identifying which should be prioritized for phasing out. According to Sara Brosché, a science adviser for IPEN, this list should include classes of chemicals rather than individual ones. “EDCs would be one very clear category” to be phased out, she told Grist, along with carcinogens and so-called “persistent organic pollutants” that don’t break down naturally in the environment.

Scientists also support listing and phasing out “polymers of concern,” the types most likely to contain EDCs and other hazardous substances. Polyvinyl chloride, for example — frequently used in plastic water pipes — can expose people to endocrine disruptors including benzene, phthalates, and bisphenols.

So far, these ideas have only been suggested for inclusion in the treaty; negotiators don’t even have a first draft yet, and are still debating whether the primary goal should be to “end plastic pollution” or to “protect human health and the environment … by ending plastic pollution.” The existing text, a laundry list of nearly every suggestion made thus far, leaves plenty of room for countries to simply “minimize,” “manage,” or vaguely “regulate” hazardous plastic chemicals, rather than eliminate them altogether. The final draft is due by year’s end, though many expect an extension, with further negotiations continuing into 2025.

To Landrigan and many others, the most important thing is that the treaty include a global cap on plastic production, which could triple by 2060 to more than 1.2 billion metric tons annually if current trends continue. That’s the weight of more than 118,000 Eiffel Towers. “We see the current exponential increase in plastic production as simply not sustainable,” he said. “It will overwhelm the planet.” Less plastic will mean fewer opportunities for EDC exposure, he added. And that will surely save lives.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Plastic chemicals are inescapable — and they’re messing with our hormones on Mar 22, 2024.