The can you set out by the curb every week may not seem so big….

The post A Day for Zero Waste appeared first on Earth911.

The can you set out by the curb every week may not seem so big….

The post A Day for Zero Waste appeared first on Earth911.

In response to growing pressure to address the plastic pollution crisis, Amazon has been cutting down on plastic packaging. Last July, the company said it used 11.6 percent less plastic for all of its shipments globally in 2022, compared to 2021. Much of Amazon’s reductions took place in countries that have enacted — or threatened to enact — restrictions on certain types of plastic packaging. But the company’s progress may not extend to the U.S., which has not regulated plastic production on a federal level.

Amazon generated 208 million pounds of plastic packaging trash in the United States in 2022, about 10 percent more than the previous year, according to a new report from the nonprofit Oceana. This packaging includes Amazon’s ubiquitous blue-and-white mailers, as well as other pouches, bags, and plastic cushioning. If all of it were converted into plastic air pillows and laid end to end, Oceana estimates it would circle the Earth more than 200 times.

“The crisis is so significant that we need change now,” said Dana Miller, Oceana’s director of strategic initiatives and an author of the report.

Miller and her co-authors are calling on Amazon to stop using plastic packaging in the U.S., citing phaseouts in some of the company’s biggest overseas markets as evidence that such a transition is possible. Amazon has done “some pretty impressive things in Europe and India, but in the U.S. they are not making the same sort of commitments,” Miller added. “The company has made great progress, but it’s just not enough.”

To calculate Amazon’s U.S. plastics footprint, Oceana used market research on the amount of plastic consumed in 2022 by the American e-commerce industry — more than 800 million pounds — and multiplied that by Amazon’s share of the market, 30.5 percent. Oceana then made some downward revisions to account for Amazon’s publicly disclosed efforts to reduce plastic packaging. For instance, in 2022, Amazon said it replaced 99 percent of its mixed-material mailers with paper ones and delivered 12 percent of its U.S. shipments in 2022 without adding any of its own packaging.

The resulting estimate, 208 million pounds, is about 11 times the weight of Seattle’s most iconic landmark, the Space Needle.

This is worrisome because the type of plastic typically used in Amazon packaging — known as “film” — is almost never recycled. Most of it is sent to landfills or incinerators, or is discarded into the environment. According to one 2020 study, plastic film is among the most common forms of marine plastic litter near ocean shores, where it kills more large marine animals than any other type of plastic. Oceana estimates that 22 million pounds of Amazon’s global plastic packaging waste generated in 2022 will end up in aquatic environments.

Plastic production causes additional concerns. The extraction of fossil fuels used to make plastic, plus the conversion of those fossil fuels into plastic products, releases carbon and air, water, and soil pollution that disproportionately affects low-income communities and communities of color.

Miller said she’d like Amazon to reduce plastics “because of a moral responsibility … to reduce their impact on the environment.” But the company has been slow to respond to moral appeals from customers and shareholders, including three shareholder resolutions since 2021 invoking plastics’ damages to marine ecosystems and human health. The resolutions, which each received more than 30 percent of shareholder votes, asked Amazon to cut plastics use globally by one-third by 2030. When announcing that it had cut plastics use globally by 11.6 percent, Amazon did not make a quantitative or time-bound commitment to further reductions.

Instead, Amazon seems to have taken its biggest steps to reduce plastic packaging in response to stringent plastic regulations, or the threat of them. “Amazon is a clever company,” Miller said. “They see things in the pipeline and they want to move early.”

In 2019, for example, Amazon India pledged to phase out plastic packaging after Prime Minister Narendra Modi called on constituents to “make India free of single-use plastic,” hinting that he would announce major restrictions on the material later that year. Within months, Amazon India said it had eliminated plastic packaging from the country’s fulfillment centers, replacing it largely with paper.

In the European Union, a directive on single-use plastics has made it unlawful since 2021 to sell several types of single-use plastic, including bags, and after a long drafting process, the bloc last month agreed to “historic” targets to reduce packaging waste by 15 percent by 2040. Amazon said in 2022 that it had eliminated single-use plastic delivery bags at its fulfillment centers across the continent.

Despite efforts from progressive lawmakers, the U.S. still lacks a federal plan to phase down plastic packaging, which could help explain why Amazon hasn’t acted more aggressively on the issue stateside. A spokesperson for the company told Grist last month that Amazon has started a “multiyear effort” to transition U.S. fulfillment centers from plastic to paper packaging, but the company has not announced a timeline for that transition.

Then again, Amazon’s American presence is also much larger than its operations overseas; the fact that U.S. orders make up nearly 70 percent of Amazon’s total sales may make it more complicated to change packaging materials here.

“It would be a bigger deal for them to eliminate plastics in the United States,” said Jenn Engstrom, director of the California chapter of the nonprofit U.S. Public Interest Research Group, who was not involved in the Oceana report. “But they’re also one of the most innovative and biggest companies in the world; just because it’s hard to do doesn’t mean they shouldn’t do it.”

Amazon, the largest e-commerce company in the world, sold more than half a trillion dollars’ worth of goods last year. Its main American competitor, Walmart, said last month that it had eliminated single-use plastic from its mailing envelopes globally. In China, the retailer JD.com is replacing disposable packaging altogether with reusable alternatives.

Engstrom pointed to some some state-level policies that could affect Amazon’s plastics use — most notably in California, where a law enacted in 2022 requires that companies reduce their overall packaging distributed in the state by 25 percent by 2032. Washington state tried to pass a similar law last year, but the proposal died in committee. Five other states have passed less specific bills on “extended producer responsibility,” or EPR, that attempt to make plastic producers financially responsible for the waste they generate — often by having them fund improvements in recycling infrastructure.

Although Amazon is funding several efforts to improve plastics recycling, Oceana says that this is “not the solution the company should be relying on.” Plastic film cannot reliably be recycled due to technical and economic constraints; virtually no curbside recycling program accepts it. In a best-case scenario, plastic film can be downcycled into plastic decking material or benches, but recent investigations suggest that store drop-off programs meant to facilitate this process often end up dumping Amazon packaging in landfills or burning it in incinerators.

When American consumers mistakenly put Amazon’s plastic packages in their curbside recycling bins — as many do — a 2022 Bloomberg investigation found that they may end up at illegal dump sites and industrial furnaces in Muzaffarnagar, India, with potentially dire consequences for nearby residents’ health.

Pat Lindner, Amazon’s vice president of mechatronics and sustainable packaging, called Oceana’s study a “misleading report with exaggerated and inaccurate information,” and told Grist that Amazon is committed to reducing its plastic footprint at U.S. fulfillment centers. A spokesperson said the company is proud of reducing its plastic footprint in Europe and India and that it would continue to share updates on its progress in the U.S. The spokesperson also said Amazon is committed to good-faith engagement with shareholders on plastic-related resolutions.

Oceana said the company declined the nonprofit’s requests for country-level data on its plastics use. The company also declined to share data on plastic packaging used in third-party shipments; Amazon’s disclosures for plastic packaging used in 2021 and 2022 only account for packages shipped from Amazon fulfillment centers.

“We are hoping that Amazon will provide more detailed data … and illuminate some of these questions,” Miller said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline As Amazon eliminates plastic packaging abroad, it’s using even more in the US on Apr 4, 2024.

Across the nation, strip malls, schools, factories, and other big, nonresidential buildings bask in the sun — a powerful, and too often wasted, source of electricity that could serve the neighborhoods that surround them.

Installing solar panels on these vast rooftops could provide one-fifth of the power that disadvantaged communities need, bringing renewable energy to people who can least afford it, according to a study by Stanford University. Although such power-sharing arrangements do exist, the research found that marginalized neighborhoods generate almost 40 percent less electricity than wealthy ones. “We were astonished to see there is still such a large difference,” said Moritz Wussow, a data and climate scientist and the study’s lead author.

This imbalance, often called the solar equity gap, is even more prevalent in the number of home installations. Placing solar arrays atop large commercial buildings could bring renewable energy to renters, while also helping homeowners who can’t afford the technology’s high upfront cost. Previous research by Wussow’s collaborators found that affluent households are more likely to benefit from tax credits and rebates designed to make solar more affordable. With Solar for All, a federal program funded by the Inflation Reduction Act, poised to give states $7 billion to create fairer access to clean energy, the study shows that harnessing commercial rooftops could be an effective way to reach two-thirds of the nation’s disadvantaged communities and begin to close that gap.

“The renewable energy transition is one of the big pillars of where the government is seeking to spend money,” said Wussow. “Our research is supposed to contribute to narrowing the equity gap, and to provide an idea of how this can be accomplished.”

Using DeepSolar, Stanford’s AI-powered database of satellite imagery, the study tallied the number of photovoltaic panels on large rooftops, at least 1,000 square feet in size, across the U.S. To help its research more readily inform policy, it examined the prevalence of these arrays in census tracts defined as disadvantaged by the federal Justice40 environmental justice initiative. These areas, which must be low income and have a second environmental burden, such as pollution, make up roughly a third of census tracts. The researchers then calculated the cost of generating solar on nonresidential buildings in those areas and found that even in states like Alaska, where the sun all but vanishes for two months each year, the costs per kilowatt would still be cheaper than the local utility rate. If businesses generate their own energy and share it, the results show residents of the surrounding neighborhoods can cash in savings and meet at least 20 percent of their annual power needs.

Despite prevailing equity gaps, community solar projects have been around for over a decade. “I like to think of it as a model, a billing mechanism, where people, regardless of whether they own or rent, can participate in the solar energy transition,” said Matthew Popkin, a U.S. programs manager at RMI, a non-profit dedicated to sustainability research. Most community solar systems rely on subscriptions, where homes connected to a local solar array pay for a share of the energy. Such programs are helping neighborhoods in cities from Denver to Washington, D.C., save money and ditch fossil fuels. “There is no one-size-fits-all approach, there is no model that will nail it for every single community, or a whole city,” Popkin said. “More creativity is probably going to help expand this further.”

Boston, a city short on open space but with plenty of rooftops, can expect to see community solar on commercial buildings expanding soon. The Boston Community Solar Cooperative, which launched this March, will begin its mission to bring clean energy to disadvantaged households with an 81-kilowatt solar array on top of a grocery store in Dorchester, one of the city’s lowest income neighborhoods. Gregory King, president of the cooperative, said the project is only possible because of solar tax credits provided by the Inflation Reduction Act. “The idea behind the model is really to create community empowerment,” he says. “And we have to create more and more, particularly rooftop solar, in an urban environment like Boston.”

Recent changes in how utilities buy back solar energy from homes, a process called net metering, has tipped residential installations into a decline. But with Solar for All funding about to pour into states as soon as July, experts like Popkin say these new resources could shape the next wave of community solar. “The biggest unknown we have right now is what some of those exact funding structures are going to look like,” he said, but inclusive planning will be key. As communities across the U.S. race to seize clean energy benefits, incentivizing businesses to go solar and share the bounty could give everyone a brighter future.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How big-box stores and schools can help marginalized communities go solar on Apr 4, 2024.

The European Union has been investing four times the amount of money into animal agriculture — which makes “artificially cheap” diets that heavily pollute the planet — than it has into plant-based farming, according to a new study.

The European Union spends almost one-third of its budget on subsidizing its common agricultural policy (CAP), reported The Guardian.

More than 80 percent of CAP funds given to farmers in 2013 went to animal products, the study said.

“The vast majority of that is going towards products which are driving us to the brink,” said Paul Behrens, study co-author and researcher of environmental change at Leiden University, as The Guardian reported.

Since large amounts of land are required to grow feed, and CAP is based mostly on land use, the subsidy program “results in perverse outcomes for a food transition,” the study explained.

“Although the CAP does not designate animal-based commodities as desirable, by disproportionally supporting livestock farming, especially when accounting for animal feed subsidies, the CAP presents an economic disincentive for transitions towards more sustainable plant-based foods,” the study said.

In order to produce equal amounts of protein, beef products need 35 times more land than grains and 20 times more than nuts.

“The global food system is responsible for approximately one-third of greenhouse gas emissions, occupies half of global habitable land and accounts for more than four-fifths of all water consumption. Current global food emissions alone will probably preclude the 1.5 °C Paris Agreement target,” the study said. “The food system is also vulnerable to the impacts of environmental and climate change, which include increasing temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns. More frequent and severe extreme weather events are already affecting food security, and additional European Union funds are already supporting farmers experiencing climate damages.”

The study, “Over 80% of the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy supports emissions-intensive animal products,” was published in the journal Nature Food.

To determine just how much the EU invests in animal products, the research team looked at subsidy records and the supply chain’s flow of public money.

“The study illustrates that most subsidies do not support an urgently needed transition towards healthy and sustainable diets,” said Florian Freund, a Braunschweig University agricultural economist who was not part of the research team, as reported by The Guardian.

Animal farming contributes from 12 to 20 percent of greenhouse gas emissions and is one of the biggest causes of decreasing wildlife numbers globally.

In its most recent CAP reform — 2023 to 2027 — the EU designated 25 percent of direct CAP payments to “eco-schemes” that incentivize environmentally friendly farming.

“CAP payments represent the largest expense (∼30%) of the total EU budget. However, the CAP lacks long-term strategic planning for transforming agricultural systems and reducing emissions. This is concerning in the face of global environmental targets required to keep within the 1.5 °C target, which requires net-zero emissions, eliminating reliance on fossil fuels and substantially reducing livestock farming within 20 years,” the study said.

The post More Than 80% of EU’s Agricultural Subsidies Goes to Animal Farming That Is ‘Driving Us to the Brink’ appeared first on EcoWatch.

Zimbabwe’s President Emmerson Mnangagwa has declared the country’s ongoing drought a national disaster, with more than $2 billion needed to feed millions.

Malawi and Zambia made similar announcements earlier this year, as an El Niño-fueled drought thrust southern Africa into a humanitarian emergency.

Mnangagwa told reporters in Harare that this year more than 2.7 million in Zimbabwe would face hunger, reported Reuters.

“No Zimbabwean must succumb or die from hunger,” Mnangagwa said in a press conference, as AFP reported. “To that end, I do hereby declare a nationwide State of Disaster, due to the El Niño-induced drought.”

The declaration frees up more resources to combat the calamity.

Zimbabwe relies heavily on hydroelectric power, and electricity production has also been impacted by the drought.

Mnangagwa said the grain harvest this season was predicted to produce a little more than half the cereals necessary to feed the country.

“[M]ore than 80% of our country received below normal rainfall,” Mnangagwa said, as reported by The Associated Press. The nation’s biggest priority, the president said, is “securing food for all Zimbabweans.”

Mnangagwa asked for humanitarian aid from local faith organizations and businesses, as well as the United Nations.

“Preliminary assessments show that Zimbabwe requires in excess of $2 billion towards various interventions we envisage in our national response,” Mnangagwa said, as Reuters reported.

Mnangagwa added that increasing food reserves by prioritizing winter crops — as well as importing grains — would be a priority for the government.

“We expect 868 273 metric tonnes from this season’s harvest. Hence, our nation faces a food cereal deficit of nearly 680 000 metric tonnes of grain. This deficit will be bridged by imports,” Mnangagwa said, as reported by Africanews.

Since November, most of Zimbabwe’s provinces have been experiencing crop failure.

The World Food Programme and other agencies have called the situation “dire,” requesting that donors give more assistance.

Angola, Madagascar, Mozambique and Botswana were also facing extreme drought conditions.

The disruption of wind patterns and warmer ocean surface temperatures associated with El Niño have led to record heat, drought and wildfires across the globe.

The current El Niño climate pattern began in the middle of last year and typically affects global temperatures for roughly one year, AFP reported.

The World Meteorological Organization has said that the current El Niño — one of the five most powerful ever recorded — will continue to impact the climate through greenhouse gases trapping heat in the atmosphere.

The post Zimbabwe Declares ‘State of Disaster’ as Drought Threatens Food Supply appeared first on EcoWatch.

Oregon Governor Tina Kotek signed a “right to repair” bill into law on March 27. The state isn’t the first to pass such a law, but the new, bipartisan legislation is considered one of the strongest of its kind in the U.S.

The law requires companies to make it easier for people to repair their own tech products and appliances. Manufacturers will be expected to offer documentation, diagnostic tools and replacement parts to consumers, so they may make their own repairs if they wish.

“As many Oregonians are struggling to make ends meet, this legislation is an opportunity to give people more choice on how to repair their devices, create pathways to saving consumers money, and reduce the harmful environmental impacts of our increased reliance on technology and the waste we create when we cannot repair,” State Representative Courtney Neron, who sponsored the bill, said in a press release.

According to Public Interest Research Groups (PIRG), Oregon has joined Massachusetts, Colorado, New York, Minnesota, Maine and California in passing right to repair laws. There are 26 other states considering similar laws, which vary in what products they cover. Several states are considering right to repair bills that address farm equipment, consumer electronics and wheelchairs.

But what makes the Oregon law stand out from existing right to repair laws around the U.S. is that it aims to prevent manufacturers from disabling some functions of a phone if users repair specific parts, which is known as parts pairing, Oregon Public Broadcasting reported. This practice connects the serial number of a part to the serial number of the device, so swapping out a part without help from an authorized repair person can cause issues with the repaired device.

The new law requires that companies give people who want to repair their items what they would need to make those repairs on fair terms, with fair terms defined as “giving independent people what they need on the same terms as people the maker authorizes to make fixes,” per the bill summary.

In addition to giving users more flexibility in repairing their own items and saving money, right to repair laws help address a growing e-waste problem. According to Statista, there are more than 50 million metric tons of e-waste generated globally every year.

“Oregon’s Right to Repair Act is about saving Oregonians money and supporting small business growth in Oregon. It provides positive environmental action by reducing e-waste, cutting pollution by manufacturing less waste and creating an after-market inventory of products to close the digital divide across our state,” Senator Janeen Sollman, chief sponsor of the bill in the Senate, said in a press release. “Oregonians deserve to have affordable and sustainable options for repairing their electronics instead of throwing them away or replacing them.”

The legislation takes effect in January 2025, and enforcement of the law will begin in 2027. The state will be able to fine manufacturers that violate the law once enforcement begins with civil penalties up to $1,000 per day.

The post Oregon Passes One of the Strongest Right to Repair Laws in the U.S. appeared first on EcoWatch.

Every single one of you has that indomitable spirit. But so many people don’t let it out. They don’t realize the power they have to influence and change the world. And so I’m saying to you, let your indomitable spirit make a difference.

— Jane Goodall, March 30, 2024, at the Moore Theatre in Seattle

Going to see Jane Goodall speak is not unlike going to a sold-out concert of one of your favorite artists. On Saturday, I arrived at the Moore Theatre in downtown Seattle, where the renowned ethologist would be talking about her life and work, to find a queue already wrapping around the block. Eager attendees — mothers and daughters, young couples, and groups of gray-haired friends — took selfies with the theater sign bearing her name. Just days before her 90th birthday (which she celebrates today, April 3), it was clear her place in the cultural landscape has yet to wane.

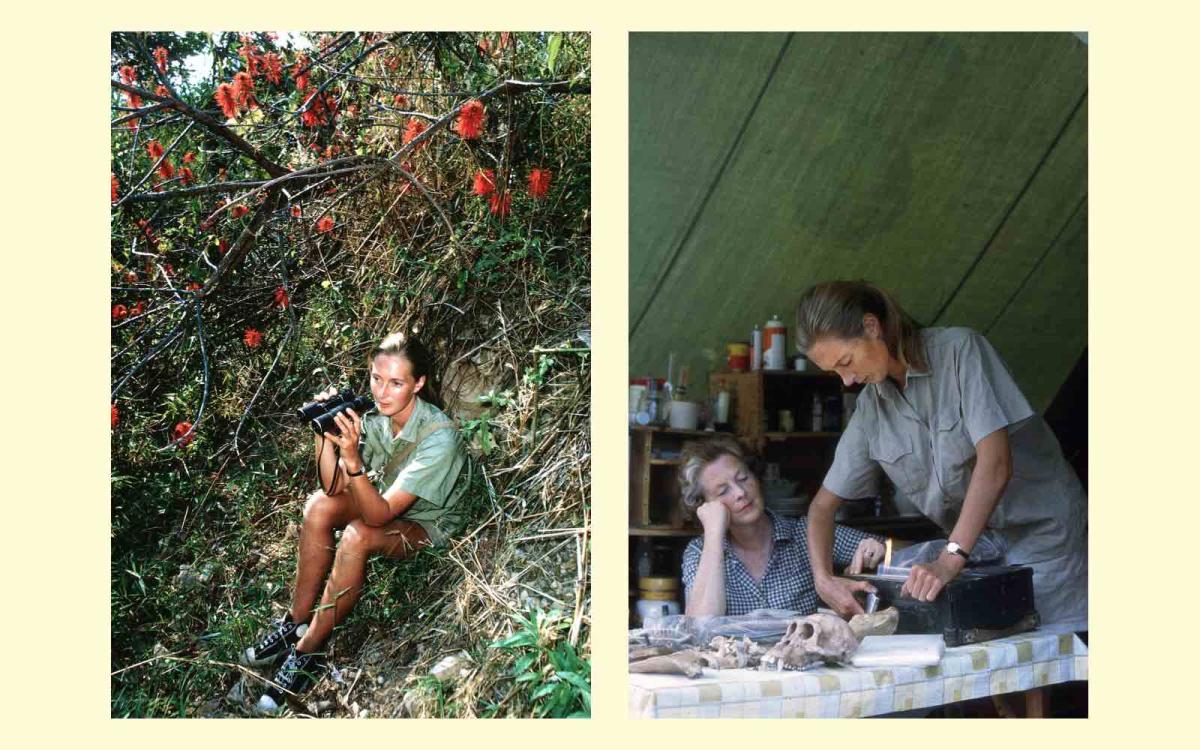

“I’ve always found this interesting about Jane — because she has spanned so many chapters in her life, depending on an individual’s age, they have a different understanding of who she is,” said Anna Rathmann, executive director of the Jane Goodall Institute. Older people may remember her as the young, beautiful blond scientist who was photographed for National Geographic, sitting with her binoculars in the Tanzanian jungle. Others may be more familiar with her work as a public speaker and advocate for conservation. “And then you talk to some of the youth activists and the younger people, they see her as this mother earth elder figure,” Rathmann said. “They see her for the wisdom that she represents. And I think that’s really powerful.”

Even as she reaches her 10th decade, Goodall has no plans to retire. She has said that she’ll keep up her demanding schedule of traveling and public speaking until her body prohibits her from doing so.

“She’ll frequently get asked by journalists, ‘Oh, Jane, you’ve lived this amazing life, you’ve done all these things, you have all these accolades. What’s your next adventure?’” Rathmann said. “And she’ll kind of sit there contemplatively, and then she’ll go, ‘My next great adventure will be death.’”

As Rathmann noted, this answer is in some ways humorous, and a bit disarming. But it’s also, of course, true. It speaks to Goodall’s genuine curiosity about the world and its natural processes — the throughline of a career that started with that curiosity about the natural world and lasted long enough to turn to the desperate need to protect it.

“There’s some connective tissue there about being deliberate and choosing to not live in fear, to not live in despair,” Rathmann said.

![]()

When I made it into the theater, nearly a full hour early, the 1,800-seat auditorium was already bustling. The people who sat behind me remarked on Goodall’s ability to “pack the house.” And just before her talk was scheduled to begin, the crowd launched into a chorus of “Happy Birthday,” followed by a standing ovation when she stepped out to the podium.

“Well, wow. That was an amazing welcome,” Goodall said.

At the start of her talk, she told us that the only way she’s able to deal with such overwhelming public admiration is because there are, as she put it, two Janes. “There’s this one standing here, just a small person walking onto a stage, with feelings like all of you. And then there’s an icon. And it’s the icon that you greeted.”

The sense of adoration for Jane the icon — and the specialness of getting to see her there in person — was almost palpable in the room. If the buzz surrounding the event had some of the atmosphere of a big concert, the talk itself felt like sitting at the feet of your own grandmother, drinking in every word of her stories.

Goodall was dressed mostly in black, with pops of red and and yellow decorating a shawl that almost resembled wings. Her hair was pulled back in its signature ponytail. Once or twice, she shared video clips on the large projector behind her. And near the end of her talk, folk musician Dana Lyons joined her onstage to sing two songs, including a tribute titled “Love Song to Jane.” But apart from that, the talk was simple and intimate. Just Goodall standing at the podium (yes, standing, the entire time) sharing in her slow, deliberate tone, stories about her life — each one building to a lesson about hope, tenacity, and our duty to the future.

Jane Goodall greets the crowd at the Moore Theatre in Seattle. Claire Elise Thompson / Grist

“I was born loving animals. And I don’t know where that came from. I was just born with it and my mother supported it,” Goodall began. She recalled how her mother took her on holiday to a farm when she was about 4 years old. For two weeks, her job was to collect the eggs from the hen house. But a young, curious Goodall wanted to understand how an egg could come out of a chicken. And so, apparently, she waited in a hen house for about four hours to witness the act — and not knowing where she was, her mother was getting ready to call the police when Goodall reappeared at the house, covered in straw, ecstatic to share the story of how a hen lays an egg.

“When you look back on that story, wasn’t that the making of a little scientist?” Goodall pondered. “A different kind of mother might have crushed that scientific curiosity. And I might not be standing here talking to you now.”

Unable to afford a college education, Goodall trained as a secretary when she was 18 (“which is very boring,” she said), and then waited tables to save money for what had been her dream since childhood: to travel to Africa and study wild animals.

She finally made it from London to Kenya, on a boat ride all the way down around Cape Town that took nearly a month, she said, to groans from the audience. “It was a magic journey,” Goodall added. In Kenya, she met the famous paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey, who happened to be in need of a secretary. Leakey ultimately arranged Goodall’s first excursion to study chimpanzees in the wild — something no researcher had done before.

When Jane arrived at what is now Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania (accompanied by her “same amazing mom”), it took several more months of patience and determination for her to even get close to the animals. But when they did eventually lose their fear of her, her discoveries, and her approach, rocked the scientific world.

Photos of Goodall and her mother at Gombe — taken by Dutch photographer and nobleman Hugo Van Lawick, whom Goodall later married. JGI / Hugo van Lawick

Chimps are humans’ closest living relatives, and Goodall found that they resemble us in some ways that were surprising and even controversial at the time. Her initial groundbreaking discovery was that chimpanzees make and use tools — something that was thought to be a uniquely human trait. But she observed other similarities as well. Chimpanzees show affection through hugging and kissing. They have complex social relationships and individual personalities. They can be brutally violent toward one another, and they can also be altruistic.

After her initial breakthrough in 1960, Goodall received funding to extend her research in Gombe, which continues to this day as the longest-running field study of chimpanzees. She first had to obtain a Ph.D. at Cambridge, where she was told she had been going about things all wrong. “You shouldn’t have named the chimps, they should have numbers, that’s scientific. You can’t talk about them having personalities, minds, or emotions. Those are unique to humans. You can’t have empathy with them because scientists must be objective.” Goodall never argued with her professors, but she considered all this to be “rubbish.”

She went back to Gombe, continuing both as a researcher and the subject of film and photographs that contributed to a shift in the way humans, including scientists, thought about animals and the natural world. “They were the best days of my life,” Goodall said. But then something else shifted.

“I just felt so at home in the forest,” she recounted. “So why did I leave? I left because, at a big conference in 1986, I came to understand the extent of the deforestation going on across Africa.” She also learned about the cruel treatment of chimps being kept in captivity for research. “I went to that conference as a scientist, planning to spend the rest of my life in Gombe. But I left as an activist. I knew I had to do something.”

Jane Goodall with a chimpanzee at the Tchimpounga sanctuary in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. JGI / Fernando Turmo

Goodall became a speaker, using the public’s interest in her life to share messages of action. She wrote and spoke directly to decision-makers, including the former director of the National Institutes of Health, Francis Collins (and, thanks in part to her advocacy, the NIH ended its use of chimpanzees in invasive biomedical research in 2015). Through the Jane Goodall Institute, she has taken a community-centered approach to conservation and habitat restoration. “Right from the beginning, we went in and asked the people what we could do to help,” Goodall said.

Around this point in her talk, Goodall described how she sees humanity “at the start of a very, very long, very, very dark tunnel. And right at the end of that tunnel is a little star shining. And that’s hope.” The tunnel is climate change. It’s also biodiversity loss, poverty, discrimination, and war, she said, and we’ve got to do what it takes to get ourselves to the light at the end.

Goodall’s stories are largely focused on the earlier parts of her life and career — stories she has probably told hundreds of times before, although that doesn’t lessen their impact. She doesn’t offer reflections about her milestone birthday, or spend much time belaboring warnings about how the world has changed over her decades of work. Although our understanding of the most pressing problems facing the world has changed, Goodall’s message largely hasn’t. The climate crisis is another issue to which Goodall applies her message of agency, empathy, and hope.

![]()

“Seeing Jane Goodall filled my cup,” said Darby Graf, a recent college graduate who now works in advocacy and inclusion in higher education. We met on the long journey down the stairs after Goodall’s talk. “There are a lot of things in this life that empty my cup, but hearing her speak filled me with hope. I didn’t know how much I craved that until I started crying partway through her speech.” (This phenomenon is apparently so widespread it is sometimes known as “the Jane effect.”)

I experienced a version of the Jane effect, too — there is something about Jane Goodall, her gentleness and accessibility, that reaches people emotionally. David Attenborough, who is himself a venerated naturalist turned climate activist, called it “an extraordinary, almost saintly naiveté.”

“Jane has an amazing capacity to view everyone as individuals,” Rathmann said. That has been a theme in her work with animals, but it also guides her approach to advocacy today, Rathmann said. “Because an individual can change their mind. An individual can create a ripple effect. And it’s a profound experience to change one individual who then can change a whole host of others.”

Rathmann added that Goodall never sought out global celebrity. But she has accepted the role of icon and given it her all. “She is keenly aware that there is someone in that audience who needs to hear whatever it is that she has said,” Rathmann said, someone who will then take that experience with them.

Still, on Goodall’s 90th birthday, sitting in the glow of Jane the icon, it’s hard not to think about Jane the human and what she herself views as her next great adventure — and whether there is anyone out there who can pick up the torch with quite the same cultural influence with which she has wielded it.

Climate journalist (and former Grist fellow) Siri Chilukuri has been a Goodall fan since the third grade, which played a big role in her decision to enter this field. Today, she said, she thinks about “how to make space for more Jane Goodalls in the world.”

“You know, how does that legacy continue? How do those conversations keep happening? How do those rooms keep filling up?” she said. Chilukuri’s reporting has focused on bringing those new voices to the fore, especially the people most impacted by the climate crisis — many of whom are also at the forefront of solutions. “There’s so many people with so many incredible stories to tell that also have to do with understanding how climate change is a threat to our world,” she said. “And those are people that we should be trying to give platforms as well.”

Goodall, for her part, has said that she respects young activists like Greta Thunberg for their anger and confrontational approach to climate activism. Although it stands in stark contrast to her tone, that anger speaks to the era of the climate crisis we are now in — an era very different from the one in which Goodall began her advocacy.

But the Jane Goodall Institute has plans to continue Goodall’s own legacy and voice as well. “Jane will always serve as that inspiration, as that figurehead of the organization,” Rathmann said of the institute’s work. “In terms of, like, 50 years from now, what is the organization? My hope is that it’s honoring Jane’s own life and legacy, having generations engaged in her work who never knew her personally, who never got the opportunity to come and see her speak in person. Several generations from now, I hope that, if we do it right, they will still be inspired and participating in this.”

“Every single one of us matters, has a role to play, makes a difference every single day,” Goodall told the crowd on Saturday. But the closing note of her talk was not about individual agency. It was about collective action.

“I just want to thank you,” she said to the team at the Jane Goodall Institute, the volunteers who support the organization’s mission, and the entire audience — those of us who simply came out to fill the room. “Because it’s together that we can make this a better world. We’ve got to get together to make a difference, now, before it’s too late.”

— Claire Elise Thompson

One of Goodall’s proudest legacies is Roots & Shoots, an initiative of the Jane Goodall Institute that aims to empower young people to be environmental leaders in their communities. The program is active in at least 75 countries — although, Rathmann noted, it’s difficult to get a complete picture of the scope because the program is grassroots in nature. Here, Goodall joins a group of youngsters releasing baby sea turtles in Santa Marta, Colombia.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Jane Goodall’s legacy of empathy, curiosity, and courage on Apr 3, 2024.

When you live far from the sprawling fields befitting utility-scale solar and wind farms, it’s easy to feel like clean energy isn’t coming online fast enough. But renewables have grown at a staggering rate since 2014 and now account for 22 percent of the nation’s electricity. Solar alone has grown an impressive eightfold in 10 years.

The sun and the wind have been the country’s fastest growing sources of energy over the past decade, according to a report released by the nonprofit Climate Central on Wednesday. Meanwhile, coal power has declined sharply, and the use of methane to generate electricity has all but leveled off. With the Inflation Reduction Act poised to kick that growth curve higher with expanded tax credits for manufacturing and installing photovoltaic panels and wind turbines, the most optimistic projections suggest that the country is getting ever closer to achieving its 2030 and 2035 clean energy goals.

“I think the rate at which renewables have been able to grow is just something that most people don’t recognize,” said Amanda Levin, director of policy analysis at the National Resources Defense Council, who was not involved in preparing the report.

In the decade analyzed by Climate Central, solar went from generating less than half a percent of the nation’s electricity to producing nearly 4 percent. In that same period, wind grew from 4 percent to roughly 10. Once hydropower, geothermal, and biomass are accounted for, nearly a quarter of the nation’s grid was powered by renewable electricity in 2023, with the share only expected to rise thanks to the continued surge in solar.

The vast majority of the nation’s solar capacity comes from utility-scale installations with at least one megawatt of capacity (enough to power over a hundred homes, according to the Solar Energy Industries Association). But panels installed on rooftops, parking lots, and other comparatively small sites contributed a combined 48,000 megawatts across the country.

“One thing that surprised a lot of different people who’ve read the report in our office was the strength of small-scale solar,” said Jen Brady, the lead analyst on the Climate Central report.

With residential and other small arrays accounting for 34 percent of the nation’s available capacity, “it lets you know that maybe you could do something in your community, in your home that can help contribute to it,” Brady said.

Still, the buildout of utility-scale solar farms continues to set the pace for how rapidly renewable energy can feed the country’s grid. According to Sam Ricketts, a clean energy consultant and former climate policy advisor to Washington Governor Jay Inslee, solar’s growth was driven by production and investment tax credits that President Barack Obama extended in 2015 and President Joe Biden expanded through the Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA. Beyond these federal incentives that allow energy developers to claim tax credits equivalent to 30 percent of the installation cost of renewables, state policies that proactively drive clean energy or promote a competitive market in which the dwindling price of renewables allow them to outshine fossil fuels have been critical to ratcheting up growth. Yet, even with the accelerating expansion seen in the last decade, more investments and incentives are needed.

“As rapid as that growth has been, how do we make it all go that much faster?” Ricketts asked. “Because we need to be building renewables and electricity at about three times the speed that we have been over the last few years.”

Achieving that rate of buildout is critical for achieving two of President Biden’s climate goals: cutting emissions economy-wide by at least half by 2030 and achieving 100 percent carbon-free electricity by 2035.

To realize those goals, the nation must reach 80 percent clean energy by 2030. “I dare say it’s even more important, for the time being, than 100 percent clean by 2035,” Ricketts said. Hitting that benchmark, he said, will require more federal and state policy pushes. Levin agrees.

“The IRA does a lot,” she said, “but it is not likely to do everything.”

The IRA has the ability to push renewable energy from roughly 40 percent of the nation’s energy mix, when nuclear is included, to more than 60 percent — or, in the most optimistic of scenarios, 77 percent.

But for the growth in capacity to be integrated into the system and utilized, the grid needs to be able to transmit electrons from far-off solar fields and wind farms to the places where they’re needed. While the transmission conversation most often revolves around building new lines and transmission towers, Levin notes that recent technology advances have made it possible to address half of these transmission needs simply by stringing new, advanced power lines on existing infrastructure that can handle bigger loads with fewer losses, in a process called “reconductoring.”

The other challenge that comes with building out clean energy is learning how to handle the way wind speeds and sunshine fluctuate. While this is often levied as an argument against their reliability, Levin points out that a host of solutions exist — from expanding battery storage to adjusting loads when demand spikes — to ensure they’re reliable. The challenge is adopting them.

“Utilities are risk averse,” she said, “and their commissions can also be risk averse. And so it’s getting them to be comfortable with thinking about the way that they provide electricity and the way that they manage their system a little differently.”

Editor’s note: The National Resources Defense Council is an advertiser with Grist. Advertisers have no role in Grist’s editorial decisions.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline US experienced staggering growth in solar and wind power over the last decade on Apr 3, 2024.

As wildfires and hurricanes wreak havoc on American communities year after year, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, or HUD, has quietly become a central part of the federal government’s response to climate change. The agency has spent billions of dollars over the past decade on long-term recovery projects that supplement emergency aid provided by FEMA, which tends to pull back from disaster areas after a few months. States have used HUD money to rebuild fire stations and hospitals, construct new flood defenses, and buy out vulnerable homes.

When Hurricane Florence spiraled over eastern North Carolina in September 2018, it damaged or destroyed more than 11,000 homes in the space of a few hours. In the aftermath of the storm, the state channeled millions of HUD dollars toward an ambitious effort to build affordable apartments in the areas that had lost big chunks of their housing stock. Restoring this low-income housing is one of the most difficult and expensive parts of disaster recovery, and the HUD money was meant to help ensure displaced renters didn’t have to scatter far and wide to find homes they could afford.

One of the first test sites for the effort was the shoreline city of New Bern, the birthplace of Pepsi. Florence damaged or destroyed almost 2,500 homes and apartments in the city and surrounding Craven County, which were too remote to attract much new investment from private builders. After the storm, the state used HUD money to build a 60-unit apartment complex called Palatine Meadows that is reserved for locals making below the area median income.

But the development may well be arriving too late to make a difference: It will open this month, more than five years after Florence struck, thanks to a mountain of federal paperwork. Documents obtained by Grist through a public records request show that it took two years to set up a program to spend the money, another year to select a site, almost two years to complete a mountain of environmental review paperwork, and another year to build the complex. This timeline was so long that it undermined the initial purpose of the project, which was to provide a timely and affordable option for residents who suddenly find themselves with nowhere to live.

Jeffrey Odham, the mayor of New Bern, says he doubts the new apartment complex will help any of the city’s storm victims.

“There’s people that will take advantage of those units, but someone who was displaced from Hurricane Florence now moving into one of these houses — I don’t think you can make that correlation, because it’s been too long,” he said in an interview with Grist. Odham didn’t know the project was part of North Carolina’s Florence recovery program until Grist informed him. It is the only subsidized apartment project in New Bern that has been built with FEMA or HUD money.

The state department that administers federal recovery funding, Rebuild NC, has faced numerous accusations of delay and financial mismanagement dating back to Hurricane Matthew in 2016. The nonprofit investigative outlet NC Newsline has reported that state officials awarded millions of dollars in building contracts to a construction firm that racked up hundreds of homeowner complaints, relocated storm victims to leaky and moldy homes or hotels that then evicted them, and delayed aid applications for years. (Rebuild NC has defended its spending decisions and blamed delays on the pandemic and supply chain shortages.)

But just as concerning is what happened for the state when everything went according to plan. Even a well-financed housing project built by a trusted developer took more than half a decade to complete.

The sluggish timeline on the New Bern development is symbolic of a much larger problem with HUD’s disaster recovery program, according to Carlos Martín, a researcher at Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies who has followed the agency’s relief efforts. By the time states can develop new housing with HUD money, he said, it’s often too late.

“I’ve heard this story before,” Martín told Grist. “They were doing everything right, and it still took forever.”

The problem starts with Congress: FEMA doesn’t need to get a green light from Congress before it starts sending money for disaster relief, but HUD does. That’s because lawmakers have never passed legislation that authorizes the agency’s disaster program on a permanent basis. Instead they pass standalone funding bills that give the agency authorization to spend on specific disasters, and a community’s recovery depends on whether it can elbow its way onto the agenda of the the House of Representatives and the Senate.

North Carolina was luckier than many places, because Congress passed such a bill mere weeks after Hurricane Florence, giving the state more than $336 million for storm recovery. Lawmakers added another $206 million the following year. By congressional standards, this was a fast turnaround: Other hard-hit areas such as Lake Charles, Louisiana, have had to wait more than a year after disasters for lawmakers to allocate funding.

The half-billion-dollar grant from HUD was far more than North Carolina could have hoped to raise on its own, but it took ages for the money to reach the state. Because Congress passes each HUD disaster allocation as a separate bill, HUD has to create new rules for how it spends each new infusion of money, then solicit public feedback on those rules in order to comply with the Administrative Procedure Act. The feds must then review and edit “action plans” from each state that receives money, making detailed decisions about what projects to fund.

North Carolina aimed high with its post-Florence action plan. Housing was the biggest need after the storm, and officials wanted to go beyond traditional FEMA programs that reimburse storm victims who relocate to hotels and existing apartments.

“These [reimbursement] programs are beneficial to renters, but may not be best suited to meet the renter recovery need of such a vast geography,” state officials wrote in a 2021 report, adding that a better approach would be “to create new housing stock in a way that is more responsive to the needs of the recovering community.”

The private market was never going to build back low-income housing on its own in eastern North Carolina. Almost all new affordable housing — whether in disaster-struck areas or anywhere else — relies on government subsidies, most notably the federal Low Income Housing Tax Credit, which allows developers to claim tax breaks for the expenses of building new units at below-market rates. But even that credit wasn’t generous enough to bring developers to the impoverished towns that had been destroyed by Florence; it would take the extra inducement of HUD money to get developers to build new low-income apartments in places like New Bern.

In 2021, after the state completed months of paperwork to set up its action plan, it sought out builders who were interested in taking advantage of the HUD money. One of the bids was from an established affordable housing developer called Woda Cooper, which owns dozens of apartment complexes across the country. Woda had found an empty lot off a major thoroughfare in western New Bern, just down the road from a high school and well inland from the coast. The lot had been vacant for decades, and it wasn’t exactly a moneymaker, but by stacking HUD money on top of other federal tax credits, Woda could make the project pencil out.

Finding the developer was only the start of the process, because the HUD funding was subject to dozens of laws and regulations that restrict how the federal government spends money. These regulations have piled up over the decades to protect wetlands, endangered species, drainage systems, historic assets, and people who live near construction sites. Together they created a set of additional hurdles that Woda and Rebuild NC had to clear before the development could break ground.

“We stress repeatedly to everyone that we’re partnering with, ‘don’t disturb any ground, don’t spend any money, don’t do anything until we clear the environmental review process and have permission from HUD,’” said Tracy Colores, the community development director at Rebuild NC, who managed the housing program.

That review process took most of 2022. In order to comply with endangered species laws, the state engaged in a monthslong back-and-forth with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to figure out whether cutting down trees on the site might threaten migration stops for the northern long-eared bat. (It didn’t.) In order to ensure the complex didn’t violate any historic preservation laws, officials sought comment from two Native American tribes, who didn’t express any concerns. There was a Superfund site at a defunct power plant almost a mile away from the lot, so the state had to check in with another state agency about the potential risk of groundwater contamination, which was nonexistent. Rebuild NC had to contact a separate department to check whether there were any underground fuel storage tanks in the area, which there weren’t, or aboveground fuel tanks that could explode, which there also weren’t.

Furthermore, a small corner of the parcel sat within a FEMA-designated flood zone. Even though the developers weren’t going to build in that corner, they did plan to cut down a few trees, which triggered another review under an executive order issued in the 1970s, which regulates flood zone construction. The state liaised with the local floodplain administrator, completed an exhaustive report on flood risks, redid site plans to add a retention pond, and ran a public notice about the proposed tree-cutting in a local newspaper — all to mitigate “temporary impacts to .01 acres” of floodplain, an area roughly the size of a two-car garage.

The state had to undertake yet another review process when they realized that a ditch on the property counted as a federally designated wetland because it contained stagnant water. The developer needed to replace two concrete culverts that drained into the ditch, expanding the 15-inch pipes to 18 inches, but under federal law this action counted as new wetland development under the Clean Water Act, which meant the developer had to seek a permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Meanwhile, the developer and the state spent months waiting for HUD approval to sell a portion of the lot that contained a cell phone tower, which conflicted with land use regulations governing the federal Low Income Housing Tax Credit.

HUD handed down final permission to use federal money for the project in November, more than four years after Florence made landfall, at which point Woda Cooper closed the deal to buy the land and started preparing the site for construction. They cleared the lot during the first half of 2023, and by the time the fifth anniversary of Florence came around, they were about halfway done building the apartments themselves. The construction timeline stretched on for a few extra months due to a supply-chain snag with the building’s electrical system, but otherwise things went according to plan. The first tenants are expected to arrive later this month.

The other developments in the state’s housing program aren’t much further along. Out of the 16 apartment projects that the state chose to fund with HUD money, 13 were in various stages of construction as of late January, including the completed Palatine Meadows. Two projects had received their authorization from HUD but haven’t yet broken ground, and one project had fallen through after the state couldn’t find a suitable developer. Meanwhile, a separate effort to rebuild one of New Bern’s largest public housing projects with money from FEMA has yet to get off the ground.

On one hand, these new low-income units would likely never have been built at all were it not for the infusion of money from HUD. Other federal programs helped Florence victims find new housing throughout the state, but the HUD money built new housing in the same places that lost it. Denis Blackburne, the senior vice president of Woda Cooper, told Grist that “without this [HUD] funding source, this development [Palatine Meadows] would not have been feasible” and that the federal money didn’t delay the building process.

On the other hand, Palatine Meadows may be arriving too late to change the trajectory of New Bern’s rebuild. Odham, the city’s mayor, says that most New Bern homeowners who suffered damage during the storm have returned and rebuilt their houses with money from insurance and federal grants. Renters, on the other hand, have almost all moved away: The city didn’t have any available apartments in the years after the storm, so renters who lost their homes had no choice but to look elsewhere for replacement housing.

“The question of whether people came back would come down to whether it was owner-occupied, or whether it’s rental property,” he said. “For rental property, I would say that most of those folks have probably turned over. They left to go find somewhere else to live.”

Martín, the Harvard researcher, says that other states like Louisiana and New York have also seen long delays when they try to develop new housing with HUD money.

“Affordable housing projects tend to take the longest for all grantees,” he said. “It certainly helps to have more housing, but if we’re looking at the people who lost their housing back in the disaster, I’m pretty sure it does very little for them.” HUD’s own inspector general found in a December report that the agency has taken longer and longer to deliver disaster funds: The average time between the passage of a disaster bill and the disbursement of funds to states tripled from around 200 days to around 600 days between 2000 and 2022.

In response to questions from Grist, a spokesperson for HUD said that the agency is working on a plan to streamline the funding process for its disaster program — and that it has asked Congress to authorize the program on a permanent basis.

Martín says Congress should also add exemptions to the environmental review process that would allow states to move through reviews faster if they’re working on affordable housing projects that are below a certain size, or projects in urban areas that are already developed. The state of California has added such exemptions to its own environmental laws as part of an effort to build more low-income housing, and a recent executive order Los Angeles mayor Karen Bass has streamlined permitting reviews for new infill housing, leading to thousands of new units. For a project like Palatine Meadows, which brought just 60 units to an existing neighborhood, such exemptions might have sped up the timeline by a year or more.

Colores, of Rebuild NC, told Grist that the housing development project was worth doing even on a prolonged timeline. She added that new apartment complexes like Palatine Meadows will ease local housing shortages and provide new housing stock that will be strong enough to withstand future storm events.

“To the extent that we can leverage these HUD dollars, we can make a significant difference in the quality and quantity of affordable housing in a lot of communities that are frequently hit by storms,” she said. However, she acknowledged that for many victims of Hurricane Florence, the ribbon-cutting on Palatine Meadows will be too late to make much of a difference.

“I wish that we could move more quickly,” she said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline North Carolina tried to rebuild affordable housing after a hurricane. It took half a decade. on Apr 3, 2024.

The PBS documentary series A Brief History of the Future was an idea whose germination accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Right around the time that the pandemic was hitting us, I realized that most of the narratives and stories about the future were based in doom and gloom, right?” said Ari Wallach, co-executive producer and host. “I call it big dystopia.”

Ari Wallach talks with Karen Washington, a farmer in Chester, New York. BetterTomorrows

Wallach is a futurist who has been investigating our planet for years, trying to determine “what does a flourishing society look like on a thriving ecologically-sound planet Earth.” One way to explore this idea was to travel with a film crew and document positive impacts around the globe. Wallach and his team visit a kelp farmer in New Haven, a solar farm in Morocco, a mycelium entrepreneur in New York state and a floating village in Amsterdam, among many other locations. The footage was molded into a six-part, six-hour documentary. The series, which covers not only climate innovators but historians, scientists and thinkers, premieres on PBS on April 3, and Wallach was part of a team that included executive producer Catherine Murdoch (married to James Murdoch, Rupert Murdoch’s son), the UNTOLD studio, and Drake’s DreamCrew production team. The following are excerpts of a conversation with Wallach from his home in Hastings-on-Hudson.

You’re sort of looking at this show as a kind of corrective to the doomsday-based climate narratives out there?

It is a corrective intervention on how we think about the future, which is – yes, there are potentially a lot of bad things that can happen. But guess what? There’s also a lot of potentially great things that can happen. What I say early on in this show is, we often think about what could go wrong, but we don’t often think about what does it look like if it goes right. And there’s multiple rights.

Were there places from your travels that stuck out for you?

It was my first time in Iceland and the folks that I met were very forward thinking. They’re like, here’s what we have. And here’s how we’re going to make it better. We’re going to tap into geothermal. We’re going to grow food in the middle of winter. We don’t have a lot of light. So, we’re going to store light. Parallel to that, when we were in India, we were in this very small village that had decided to go almost completely solar. This was much more of like, here’s how we lean into better futures environmentally, sustainably and for our own health. And that mindset was very different from the one that I’ve been kind of enmeshed in for the past decade plus, especially in the kind of clean green energy space.

When you see these micro examples of people doing things at the very local level, how did that change how you think about things, or did it at all?

A lot of what I did as a kind of host and a guide was pull myself out of the usual rooms that I’m in. I’m in a lot of conference rooms and a lot of organizations… Seeing folks who were acknowledging where they were and where we are as a species on this planet right now, but then saying, okay, let’s acknowledge, but let’s move forward, and move forward in a way that is not pollyannish rainbows and unicorns, but move forward in a way where it’s like, every little bit counts.

You know, I go back to this quote that I always attribute to Al Gore, but I don’t know if it’s really from him. There’s no silver bullet. It’s a silver buckshot. A lot of what we did in our travels was finding the people who are doing the silver buckshot.

When you visited Ecovative (a company producing food, leathers, and materials from mycelium, a fungi) how scalable do you think something like that is and how optimistic does that make you feel about where we can go with food production?

Let’s go back a hundred-ish years to the first couple of oil derricks in Tulsa or the Permian Basin. And now look at the global footprint of oil and big oil. No one back then thought it would scale to being basically how you run a planet. Whether it’s mycelium for food production or for energy or for building materials, people say, well, how can that scale? Look around. A gas station on every corner, a car in front of every home more or less, we scaled it, it worked. And that wasn’t even driven by an emergency. That was just driven by economics. So, imagine if you have economics and a little bit of an emergency situation — that stuff can scale.

You introduce this concept of the intertidal moment – the moment between things in the ocean. But what does this mean for our species?

As a society we’re at an intertidal between what was and what will be. What the show really does is it brings to light different folks and projects and ideas that are for the intertidal moment. They are emblematic of an intertidal mindset of, we got to take a little bit about what we did before, mix it in with this kind of the chaos of the current moment and point us towards what we want. But none of them claim to be the perfect example of the next paradigm. What we show in the series are folks who are doing that with an open, innovative mindset, whether it’s in technology or food or housing or how we think about democracy or even human psychology.

Your team also visits with Boyan Slat (founder of The Ocean Cleanup). What was that like?

The takeaway from Boyan Slat isn’t just what they’re doing, because what they’re doing is very fascinating. They’re cleaning up rivers and taking microplastics or plastic that became microplastics out of the ocean and therefore out of the fish. He basically said, everyone kept saying this is impossible. You can’t do anything. And he just kept saying, what if we just go and clean it up? He said, not everything has to be pie in the sky, Manhattan-project level. Sometimes you just have to do it.

What would you say to people who are becoming overly cynical about climate breakdown?

It’s hard not to be cynical about the fate of our species on planet Earth. We have to recognize, though, that those aren’t all the stories of what’s happening. There are two things you can do. One, curate what comes into your mind… think about the stories that are perpetuated algorithmically to us. These algorithms are receptive to what it is that we’re clicking on. So be careful and think about what you want more of coming on to your information plate. Two, there are things that you need to do in your daily life. We had a lawn, and we’re letting it go to a meadow. What does Ari’s little piece of land have to do with, you know, creating a pollinator pathway? But that helps avoid the cynicism knowing that you’re doing something. There are bigger things. You can donate to candidates. You can march. You can rally. The key thing, though, is to recognize that you have agency, both for your own actions and those around you.

A Brief History of the Future premieres April 3 on PBS. Watch the trailer below.

The post New PBS Documentary Focuses on a More Hopeful Future appeared first on EcoWatch.