Although period products are relatively small items, nearly 20 billion sanitary napkins, tampons, and applicators…

The post 5 Zero-Waste Period Products appeared first on Earth911.

Although period products are relatively small items, nearly 20 billion sanitary napkins, tampons, and applicators…

The post 5 Zero-Waste Period Products appeared first on Earth911.

For the first quarter of 2024, electricity generation from wind power sources exceeded the amount of electricity generated by fossil fuel sources in the UK. Further, electricity from fossil fuels reached a record low on April 15.

According to data from Ember, a not-for-profit energy think-tank, electricity generation from wind energy sources reached 25.3 terawatt hours (TWh), or about 39.4% of total electricity generation, in the first three months of 2024. By comparison, electricity from fossil fuel sources reached 23.6 TWh, about 36.2% of total electricity generation, during the same time period, Reuters reported.

In January, electricity generation from wind energy was at 9.07 TWh, followed by 8.24 TWh in February and 7.96 TWh in March. Electricity generation from coal reached 0.48 TWh (January), 0.22 TWh (February) and 0.34 TWh (March), while gas contributed to 9.65 TWh, 6.27 TWh and 5.90 TWh for January, February and March, respectively. Other fossil fuel sources made up 0.25 TWh in January, 0.24 TWh in February and 0.23 TWh in March.

As Reuters reported, wind and solar energy combined to provide 27.1 TWh of electricity generation in the UK during the first quarter of 2024, leading to a record high of 42.2% share of electricity generation from renewable energy sources.

Progress appears to continue into the second quarter, as electricity generation from fossil fuels in the UK reached a record low on April 15, according to a report from Carbon Brief. The report showed that electricity output from fossil fuel sources made up an all-time low of 2.4% for one hour on April 15.

These milestones are moving the needle on a target from the National Grid Electricity System Operator (NGESO) to run the electrical grid in the UK without fossil fuels, at least for short periods, by 2025, Carbon Brief reported.

“This hasn’t just happened overnight. It’s been a culmination of a significant amount of effort over a number of years,” Craig Dyke, director of system operations at NGESO, told Carbon Brief. “That’s not just us [NGESO] operating in isolation, that’s planning and collaboration with industry, with [energy regulator] Ofgem and with the government… It’s not just about technologies, it’s about hearts and minds and processes and systems and people working together.”

The UK has targeted net-zero by 2050, including through the transition to renewable energy sources.

According to Ember, in 2010, about one-third of the UK’s energy generation came from coal, and by 2022, coal power generation fell to only 2%. As Carbon Brief reported, about one-third of electricity generation in England, Scotland and Wales was from all fossil fuels as of 2023, while renewables made up about 40% of electricity generation.

The post Renewable Electricity Generation Outpaces Fossil Fuels for Record Time Span in UK appeared first on EcoWatch.

The more plastic a company makes, the more pollution it creates.

That seemingly obvious, yet previously unproven, point, is the main takeaway from a first-of-its-kind study published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances. Researchers from a dozen universities around the world found that, for every 1 percent increase in the amount of plastic a company uses, there is an associated 1 percent increase in its contribution to global plastic litter.

In other words, if Coca-Cola is producing one-tenth of the world’s plastic, the research predicts that the beverage behemoth is responsible for about a tenth of the identifiable plastic litter on beaches or in parks, rivers, and other ecosystems.

That finding “shook me up a lot, I was really distraught,” said Win Cowger, a researcher at the Moore Institute for Plastic Pollution Research and the study’s lead author. It suggests that companies’ loudly proclaimed efforts to reduce their plastic footprint “aren’t doing much at all” and that more is needed to make them scale down the amount of plastic they produce.

Significantly, it supports calls from delegates to the United Nations global plastics treaty — which is undergoing its fourth round of discussions in Ottawa, Canada, through Tuesday — to restrict production as a primary means to “end plastic pollution.”

“What the data is saying is that if the status quo doesn’t change in a huge way — if social norms around the rapid consumption and production of new materials don’t change — we won’t see what we want,” Cowger told Grist.

That plastic production should be correlated with plastic pollution is intuitive, but until now there has been little quantitative research to prove it — especially on a company-by-company basis. Perhaps the most significant related research in this area appeared in a 2020 paper published in Environmental Science and Technology showing that overall marine plastic pollution was growing alongside global plastic production. Other research since then has documented the rapidly expanding “plastic smog” in the world’s oceans and forecasted a surge in plastic production over the next several decades.

The Sciences Advances article draws on more than 1,500 “brand audits” coordinated between 2018 and 2022 by Break Free From Plastic, a coalition of more than 3,000 environmental organizations. Volunteers across 84 countries collected more than 1.8 million pieces of plastic waste and counted the number of items contributed by specific companies.

About half of the litter that volunteers collected couldn’t be tied to a specific company, either because it never had a logo or because its branding had faded or worn off. Among the rest, a small handful of companies — mostly in the food and beverage sector — turned up most often. The top polluters were Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Nestlé, Danone, Altria — the parent company of Philip Morris USA — and Philip Morris International (which is a separate company that sells many of the same products).

More than 1 in 10 of the pieces came from Coca-Cola, the top polluter by a significant margin. Overall, just 56 companies were responsible for half of the plastic bearing identifiable branding.

The researchers plotted each company’s contribution to plastic pollution against its contribution to global plastic production (defined by mass, rather than the number of items). The result was the tidy, one-to-one relationship between production and pollution that caused Cowger so much distress.

Many of the top polluters identified in the study have made voluntary commitments to address their outsize plastic footprint. Coca-Cola, for example, says it aims to reduce its use of “virgin plastic derived from nonrenewable sources” by 3 million metric tons over the next five years, and to sell a quarter of its beverages in reusable or refillable containers by 2030. By that date the company also aims to collect and recycle a bottle or can for each one it sells. Pepsi has a similar target to reduce virgin plastic use to 20 percent below a 2018 baseline by the end of the decade. Nestlé says it had reduced virgin plastic use by 10.5 percent as of 2022, and plans to achieve further reductions by 2025.

In response to Grist’s request for comment, a spokesperson for Coca-Cola listed several of the company’s targets to reduce plastic packaging, increased recycled content, and scale up reusable alternatives. “We care about the impact of every drink we sell and are committed to growing our business in the right way,” the spokesperson said.

Similarly, a PepsiCo representative said the company aims to “reduce the packaging we use, scale reusable models, and partner to further develop collection and recycling systems.” They affirmed Pepsi’s support for an “ambitious and binding” U.N. treaty to “help address plastic pollution.”

Three of the other top polluting companies did not respond to a request for comment.

It’s worth noting that many of the companies’ plans involve replacing virgin plastic with recycled material. This does not necessarily address the problem outlined in the Science Advances study, since plastic products are no less likely to become litter just because they’re made of recycled content. There’s also a limit to the number of times plastic can be recycled — experts say just two or three times — before it must be sent to a landfill or an incinerator. Many plastic items cannot be recycled at all.

Richard Thompson, a professor of marine biology at the University of Plymouth in the U.K., commended the researchers for making “a very useful contribution to our understanding about the link between production and pollution.” He said the findings could shape regulations to make companies financially responsible for plastic waste — based on the specific amount they contribute to the environment.

The findings could also inform this week’s negotiations for the U.N. global plastics treaty, where delegates are continuing to spar over whether and how to restrict production. According to Cowger, if the treaty really aims to “end plastic pollution” — as it states in its mandate — then negotiators will need to think beyond voluntary measures and regulate big producers.

“It’s not going to be Coca-Cola or some other big company saying, ‘I’m gonna reduce my plastic by 2030, you’ll see,’” Cowger told Grist. “It’s gonna be a country that says, ‘If you don’t reduce by 2030, you’re going to get hit with a huge fine.’”

This story has been updated to include a response from PepsiCo.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline The more plastic companies make, the more they pollute on Apr 24, 2024.

Hey there, Looking Forward fam. Happy Earth Day (and Earth Week, and Earth Month) — a time of year when sustainability is elevated in the global consciousness, and my inbox is full of vaguely greenwashy PR pitches.

Each April, I (and every other climate journalist) revisit the same debate: whether to “cover Earth Day” in some way, or ignore it on account of the fact that we’re immersed in these issues every day. But it struck me that Earth Day 2024 has a particularly timely theme: Planet vs. Plastics. The official Earth Day organization has been assigning yearly themes since at least 1980, and Planet vs. Plastics is hitting in the year when U.N. members are supposed to be finalizing a global treaty to address plastic pollution.

“We’ve had research for 30 years now saying that plastics are dangerous to our health,” said Aidon Charron, director of End Plastic Initiatives at EarthDay.org. But he and others at the organization chose plastics as this year’s focus because they saw a gap in public knowledge, both about the harm that plastics can cause and about the policy solutions that are currently being debated on an international stage. Discussions about plastic tend to focus on individuals doing their part by reducing, reusing, and recycling, Charron said — but “we’re not going to simply recycle our way or technology our way out of this problem.”

Charron and other advocates have been pushing for ambitious targets in the global plastics treaty, and EarthDay.org is circulating a petition, which currently has over 22,000 signatures, for some of its key objectives, which include banning the export and incineration of plastic waste and a “polluter pays” principle. “What we don’t want to see is something similar to the Paris Climate Agreement,” said Charron. “While that was a great agreement, the issue is it’s voluntary, and so countries can opt in and opt out. And there’s also no punishment if somebody doesn’t meet the standards they set for themselves.”

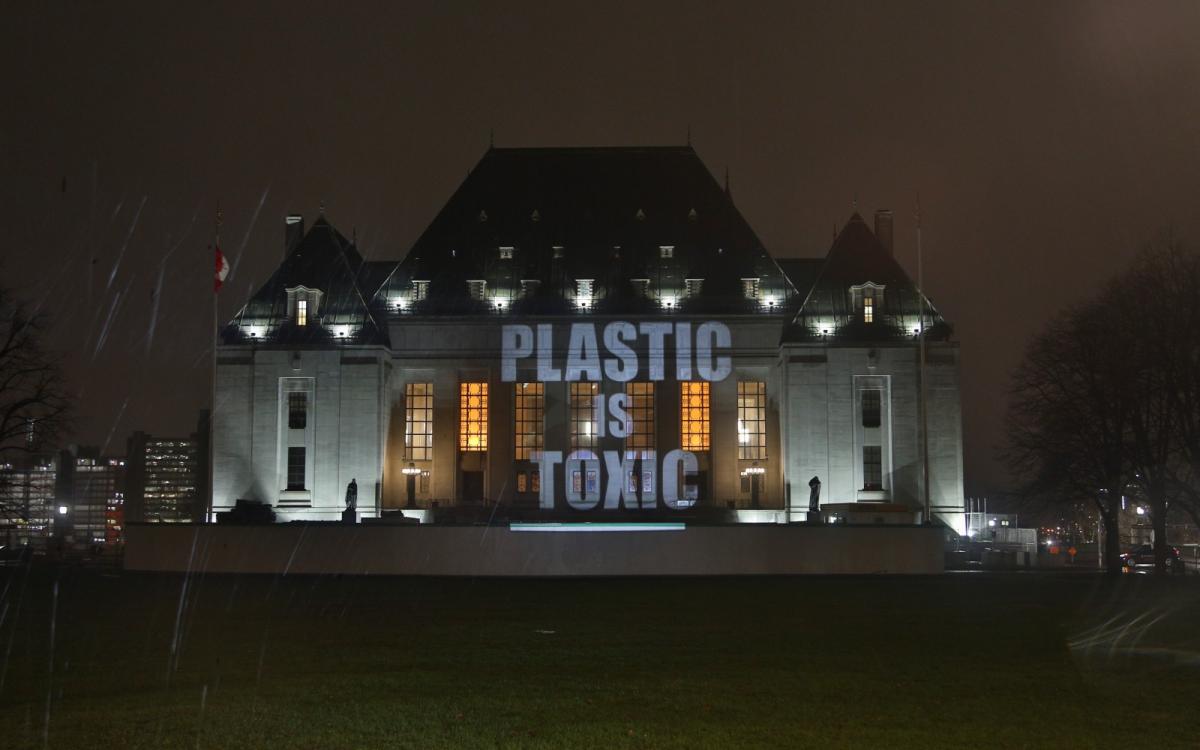

On Sunday, EarthDay.org and other campaigners organized a march in Ottawa, demanding a strong and ambitious global plastics treaty. EARTHDAY.ORG

But the negotiations on the treaty have been fraught with competing interests — and even as the deadline nears, much remains to be sorted out. This week, delegates and advocates are gathering in Ottawa, Canada, for the fourth intergovernmental negotiating committee, or INC-4 — the second-to-last session on the books before the U.N.’s self-imposed deadline to finalize the agreement at the end of this year. As the parties have failed to make significant progress at the previous three meetings, the stakes at INC-4 are high.

So, today, I’m turning the newsletter over to the capable hands of my colleague Joseph Winters, who covers the plastics industry and has been following the negotiations of the global plastics treaty for the past two years. Read on a primer on the history of the treaty, the solutions being proposed in it, and where things stand as negotiators head into another round of discussions this week.

— Claire Elise Thompson

![]()

To understand the global plastics treaty, it’s helpful to go back to the 2022 U.N. Environment Assembly meeting, where delegates agreed to write it. By then, plastics had long been considered an environmental scourge. The world was — and still is — producing more than 400 million metric tons of the material every year, almost entirely from fossil fuel feedstocks. Just five years prior, researchers had shown that 91 percent of the world’s plastics were not recycled due to high costs and technological barriers.

Agreeing to write some kind of treaty was seen as a big success, but the icing on the cake was the promise to address not only plastic litter, but “the full life cycle” of plastics. This opened the door to discussions around limiting plastic production, which most experts consider to be a nonnegotiable part of an effective mitigation strategy for plastic pollution. They liken it to an overflowing bathtub: better to “turn off the tap” — i.e., stop making plastic — rather than try to mop up the floor while the water’s still running.

Experts see the treaty as a critical opportunity to stop the fossil fuel industry’s pivot to plastic production, as the world begins to phase out oil and gas from transportation and electricity generation. None of the details are even close to being finalized — but observers have called the treaty the “most significant” international environmental deal since 2015, when countries agreed to limit global warming under the Paris Agreement. And advocates hope that this agreement will ultimately have even more teeth.

Under a very optimistic scenario, it could include global, legally binding plastic production caps for all U.N. member states, plus some details on how rich countries should help poorer ones achieve their plastic reduction targets. The treaty might ban particular types of plastic, plastic products, and chemical additives used in plastics, and set legally binding targets for recycling and recycled content used in consumer goods. It could also chart a path for a just transition for waste pickers in the developing world who make a living from collecting and selling plastic trash. But such a far-reaching agreement is by no means guaranteed; some countries and industry groups are working hard to water down the treaty’s ambition, and have thus far limited negotiators’ progress.

![]()

When delegates first met in Punta del Este, Uruguay, in November 2022, it became clear that a vocal minority of countries — mostly oil-producing states including Saudi Arabia and Russia, as well as the U.S., to some extent — wanted to bend the treaty away from plastic production limits by focusing instead on better recycling and cleanup efforts. Petrochemical companies are also pushing for a focus on recycling, despite their trade groups knowing since the 1980s that plastics recycling would be unable to keep up with booming production.

This disagreement — production versus pollution — has been central to each meeting since then, stalling progress at every turn. Although delegates have held important discussions on plastic-related chemicals and the impact of the treaty on frontline communities, by the end of INC-3 last November, negotiators still hadn’t written anything beyond a so-called “zero draft,” basically a laundry list of options and suboptions for various parts of the treaty. They also failed to agree on an agenda for “intersessional” work between INC-3 and INC-4, meaning they could not use those intervening months to continue formal discussions, although several countries arranged unofficial meetings.

In a provisional note released ahead of this week’s negotiations, INC chair Luis Vayas Valdivieso made paring down the revised zero draft a key priority for delegates at INC-4. The committee should “streamline” the document, he wrote, and set an agenda for intersessional work to be completed in the months between INC-4 and INC-5.

“INC-4 is going to be likely the most important of all the INCs,” said Ana Rocha, global plastics program director for the nonprofit Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives.

The march on Sunday began with a rally outside of Parliament Hill, where crowds heard from activists and Indigenous leaders who traveled from all over the world to join the demonstration. EARTHDAY.ORG

One of the key priorities for advocates is some kind of quantitative production limit. “If the goal is to end plastic pollution, it’ll be really hard to do without a cap on virgin plastic production,” said Douglas McCauley, an associate professor of ecosystem ecology at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Some of the most specific recommendations are based on plastic’s contribution to climate change. To limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit), the nonprofit Pacific Environment calculated last year that global plastic production should be cut by 75 percent by 2050, compared to a 2019 baseline. The Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives has proposed a 12 to 17 percent reduction every year starting in 2024.

A so-called “high-ambition coalition” of countries — including Norway, Rwanda, Canada, Peru, and a host of small island and developing states — say they support production limits as part of the plastics treaty, although they have not yet rallied around a particular target. It’s also possible that the treaty will have to rely on indirect measures to restrict plastic production, like bans on single-use plastics or a tax on plastic packaging.

![]()

Public health has emerged as another major, and surprisingly popular, priority for the treaty. Even in the two short years since world leaders first agreed to broker a treaty, lots of new evidence has emerged to highlight the human and environmental health risks associated with plastics. Last month, scientists raised the number of chemicals known to be used in plastics from 13,000 to 16,000. More than 3,000 of these substances are known to have hazardous properties, while a much larger fraction — about 10,000 — have never been assessed for toxicity. According to one recent analysis from the nonprofit Endocrine Society, plastic-related health problems cost the U.S. $250 million per year.

As of last November, more than 130 countries supported incorporating human health into the treaty’s primary objective, and many explicitly said they wanted the agreement to somehow control problematic chemicals. This is currently reflected in the zero draft, in proposals to prioritize “chemicals and polymers of concern,” putting them first in line for bans and restrictions. Some substances that would likely be included on this list are polyvinyl chloride, or PVC — the plastic used to make water pipes and some toys — as well as endocrine-disrupting chemicals like phthalates, bisphenols, and PFAS.

Bjorn Beeler, general manager and international coordinator for the nonprofit International Pollutants Elimination Network, said that chemicals are the most “matured” part of the treaty.

Other sections, however — like the financial details of how countries will pay for the provisions of the agreement — have been largely unaddressed. With so much left to negotiate and so little time, questions are swirling around whether there will have to be an additional meeting after INC-5, or perhaps an INC-4.1 during the summer.

For now, many environmental advocates say it’s important that negotiators stick to the original schedule, running INC-4 under the assumption that they can and will finish the treaty by 2025. Should they need an extension, they can consider how best to coordinate that at a later date. Rocha, with the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives, said she’d rather extend the timeline than rush through a weak agreement.

“More important than an ambitious timeline is an ambitious treaty,” she said.

— Joseph Winters

Last call for the Looking Forward drabble contest! This is the final week to share your 100-word vision for a clean, green, just future, for a chance to win presents.

To submit: Send your drabble to lookingforward@grist.org with “Drabble contest” in the subject line, by the end of Friday, April 26 (two days away)!

Here’s the prompt: Choose ONE climate solution that excites you, and show us how you hope it will evolve over the next 100 years to contribute to building a clean, green, just future. We’ve covered a boatload of solutions you could draw from (100, in fact!) — so if you need some inspiration, peruse the Looking Forward archive here.

Drabbles offer little glimpses of the future we dream about, so paint us a compelling picture of how you hope the world, and our lives on it, will evolve.

Here’s what we’re looking for:

The winning drabbles will be published in Looking Forward in May, and the winners will receive presents! Some Grist-y swag, and a book of your choice lovingly packaged and mailed to you by Claire.

On Monday (Earth Day), in collaboration with a conservation organization called Oceana Canada, EarthDay.org projected an illuminated message onto the Canadian Supreme Court building in Ottawa, reading “plastic is toxic.” Similar messages were also projected onto Parliament Hill and the Canadian National Arts Centre, sending a clear message to leaders ahead of the treaty negotiations this week.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline On the agenda this Earth Day: A global treaty to end plastic pollution on Apr 24, 2024.

Despite its other environmental impacts, including toxic waste that requires centuries or millennia of storage…

The post Best of Earth911 Podcast: Can Nano Nuclear Energy’s Microreactors Deliver Equitable Electricity? appeared first on Earth911.

Ewaste remains a massive problem. We’re two high school students who launched Ecoolair, a solar-powered…

The post Ecoolair: Two High Schoolers Trying To Make A Difference appeared first on Earth911.

Last fall, I invited a stranger into my yard.

Manzanita, with its peeling red bark and delicate pitcher-shaped blossoms, thrives on the dry, rocky ridges of Northern California. The small, evergreen tree or shrub is famously drought-tolerant, with some varieties capable of enduring more than 200 days between waterings. And yet here I was, gently lowering an 18-inch variety named for botanist Howard McMinn into the damp soil of Tacoma, a city in Washington known for its towering Douglas firs, bigleaf maples, and an average of 152 rainy days per year.

It’s not that I’m a thoughtless gardener. Some studies suggest that the Seattle area’s climate will more closely resemble Northern California’s by 2050, so I’m planting that region’s trees, too.

Climate change is scrambling the seasons, wreaking havoc on trees. Some temperate and high-altitude regions will grow more humid, which can lead to lethal rot. In other temperate zones, drier springs and hotter summers are disrupting annual cycles of growth, damaging root systems, and rendering any survivors more vulnerable to pests.

The victims of these shifts include treasured species from around the globe, including certain varietials of the Texas pecan, the towering baobabs found in Senegal, and the expansive fig trees native to Sydney. In the Pacific Northwest, I’ve seen summer heat domes turn our region’s beloved conifers into skeletons and prolonged dry spells wither the crowns of maples until the leaves die off in chunks.

The world is warming too quickly for arboreal adaptation, said Manuel Esperon-Rodriguez, an ecologist at Western Sydney University who researches the impact of climate change on trees. That’s especially true of native trees. “They are the first ones to suffer,” he said.

Urban arborists say planting for the future is urgently needed and could prevent a decline in leafy cover just when the world needs it most. Trees play a crucial role in keeping cities cool. A study published in 2022 found that a roughly 30 percent increase in the metropolitan canopy could prevent nearly 40 percent of heat-related deaths in Europe. The need is particularly acute in marginalized communities, where residents — often people of color — live among treeless expanses where temperatures can go much higher than in more affluent neighborhoods.

While the best solution would be to stop emitting greenhouse gases, the world is locked into some degree of warming, and many regional governments have begun focusing on building resilience into the places we live. Urban botanists and other experts warn that cities are well behind where they should be to avoid overall tree loss. The full impact of climate change may be decades away, but oaks, maples, and other popular species can take 10 or more years to mature (and show they can tolerate a new climate), making the search for the right varieties for each region a frantic race against time.

In response, scientists and urban foresters are trying to speed up the process, thinking strategically about where to source new trees and using experiments to predict the hardiness of new species. Beyond that, many places are moving past the idea that native species are the most sustainable choice by default.

“Everybody is looking for the magic tree,” said Mac Martin, who leads the urban and community forestry program at Texas A&M’s Forest Service. He went on to say that one kind of tree isn’t enough. We need “a high number of diverse trees that can survive.”

In other words, a whole new urban forest.

In late 2023, that quest took Kevin Martin, no relation to Mac, to the arid forests of Romania. As the head of tree collections at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, he spent a week hiking through pine-scented forests to gather beech acorns. He brought seeds from seven species back to the U.K. and planted them in individual pots at the botanical garden’s nursery. Now, he waits.

He hopes the trees will thrive in London’s drier springtime soils, which are making it hard for old standbys like the English oak to survive the hotter summers that follow. The research is part of a bigger change for the botanical garden, Martin said, which historically focused on collecting rare plant specimens. “We’re flipping that on its head and looking at what we want to grow,” he said. “We want a good outcome for humanity.”

Under normal conditions, trees are among the best defenses against heat, and not just because they provide a shady place to rest. As their leaves transform sunlight into energy, trees give off water vapor through tiny holes called stomata, cooling the air around them with “nature’s own air conditioning,” Martin said.

But increasingly hot temperatures can shut down this process. In extreme dry heat, the cells slacken and the stomata close, stopping water from escaping. The point at which this happens is called the turgor loss point, and it’s like the leaves on a houseplant wilting. If a stressed tree doesn’t get water, its leaves will overheat and die before the fall, sometimes across entire sections of the crown. In highly humid conditions, the air holds too much water vapor to absorb any more, leaving leaves waterlogged and beckoning rot. Even if a tree in this condition looks healthy, it can’t cool cities as well as it used to. Making matters worse, distressed plants are more vulnerable to pests like the borer beetle.

Native trees are particularly at risk for climate stress, and in many cities, they make up a significant chunk of urban tree cover. Eighty-seven percent of the trees in Plano, Texas, are native species, for example. That number is 66 percent in Santa Rosa, California, and 30 percent in Providence, Rhode Island.

To be sure, non-native trees have been a part of human settlements for a long time. Plants often spread with human migration, and European colonists brought many species to other continents. Many of these newcomers grow faster than the indigenous varieties, and some have proven better suited to urban areas.

However, flora introduced from far away can also experience climate shock. Currently, non-native trees typically come from climates similar to those trees they now stand alongside. Until the seasons started going haywire, this made them well-suited to their adopted homes. For example, the London plane, a cross between an American sycamore and a plane tree from western Asia, lines streets in temperate zones around the world. Now, scientists are worried about the tree’s future in its namesake city as dry springs and hot summers leave them weak and susceptible to pests.

To find solutions, researchers are studying which trees could do better than those currently struggling in rapidly warming cities, with an eye toward species that have already adapted to drier regions hundreds or even thousands of miles away. In Canada, for example, scientists have matched trees from the northern United States with the expected climates in cities including Vancouver, Winnipeg, and Ottawa. Urban foresters in Sydney are considering the trees in Grafton, an Australian city about 290 miles closer to the equator.

Thinking of a future U.K., Kevin Martin started evaluating trees from the steppes of Romania more than 1,000 miles away. To find the right places to collect acorns, Martin looked at both temperature and the amount of water available in the soils of Romanian forests, explaining that trees in moist soils in tropical rainforests or near rivers will keep going even in hot conditions.

He will have to wait two years for the acorns to sprout and grow into saplings. Only then can he begin stress-testing the specimens to see if the trees are a good fit for the growing conditions of London in 2050 and beyond. Martin plans to study at what point the trees’ leaves hit turgor loss in dry, hot conditions. But crucially, the trees must also be able to adapt to London’s cold winters, which are expected to stay freezing even as drought and heat waves increase.

Examining leaf turgor loss can’t be used to assess trees for every neighborhood in a city. Parts of Sydney are facing increasingly humid summers in an otherwise temperate climate. With this in mind, the municipal forestry department used a database that matches a far-off location’s current humidity with what experts expect for the city in 2050. In addition to considering temperature, officials hope to increase tree canopy to cover 27 percent of the city in the next quarter century. They are also mindful that the climate will change gradually and have laid out a phased planting plan. Trees that thrive in the Sydney of 2060 may struggle in 2100.

Such factors are on Mac Martin’s mind as his department updates Texas A&M’s online tree selector, a statewide database that recommends species, to include varieties that are likely to flourish in the future.

Texas is slated to experience a triple climate whammy of hotter summers, colder winters, and changing humidity, with some places becoming intolerably dry and others getting more muggy. It’s a complex weather pattern to plant for — and that’s assuming cities are prepared to adapt once the right species are identified.

As risky as it may seem to hold on to endemic species in the face of climate change, some governments continue to create policies that favor native trees over non-natives. Canada, for example, has funded the planting of thousands of native trees in urban areas through its 2 Billion Trees project.

Botanists like Henrik Sjöman, who oversees collections at the Gothenburg Botanical Gardens in Sweden, say native-only thinking can leave cities unprepared to adapt to climate change. But he doesn’t believe cities must completely abandon native species. He hopes that some species can be saved with a process he calls “upgrading.” The idea is to find trees from the same species that are already growing in harsher conditions, and propagate seeds from those plants. To grow more resilient English oaks in the U.K., for example, scientists could grow them from acorns sourced from western Asia, where the tree also grows. These acorns would come from trees thriving in a more arid region, so they could potentially yield hardier varietals that will one day thrive in a drier London.

Additionally, locale-adapted native species might continue thriving in woodlands like large city parks or green spaces. Sjöman said it’s possible that trees in undeveloped areas will have more time to adapt to climate change, because rainfall more easily soaks into the ground and fills the water table. That’s not the case in highly paved and built-up neighborhoods, where decreasing rainfall hurts trees more.

“Everything’s pushed to its limit in urban environments,” Sjöman said.

That reality has many locales taking a “block-by-block” approach to planting guidelines. Toronto, for example, plants trees from the region’s ecosystem whenever possible, said Kristjan Vitols, the city’s supervisor of forest health care and management. That’s especially true of its iconic ravines, where newly planted trees must be endemic — and raised from locally sourced seeds when possible. But the city is also open to non-native species where plants face harsh conditions along streets.

The rules for Toronto’s ravines are based on the idea that a species will develop traits specific to a location as they grow over many generations. As a result, trees grown from seeds gathered in Toronto may be more likely to blossom when native pollinators are active than seeds from the same species grown at a lower latitude.

Foresters say there’s another valid argument for trying to keep as many native trees as possible. For some First Nations and Indigenous people with deep ties to particular varieties, phasing them out could add to the long history of cultural and physical dispossession.

In the Pacific Northwest, for example, the Western redcedar (written as one word because it’s not a true cedar) is central to Native American cultural practices for many local tribes. Some groups refer to themselves as the “people of the cedar tree,” using the logs for canoes, basketry, and medicine.

But drying soils mean the tree is no longer thriving in many parts of Portland, Oregon, said Jenn Cairo, the city’s urban forestry manager. The city has faced deadly heat domes and drier conditions in recent years. As a result, Portland only recommends planting the species in optimal conditions in its list of approved street trees. “We’re not eliminating them,” she said, “but we’re being careful about where we’re planting them.”

A similar tactic is being used in Sydney, where the Port Jackson fig tree is struggling, but a close relative, the Moreton Bay fig, is thriving. Head of urban forestry Karen Sweeney said the city is looking at irrigated parklands as potential homes for native species that are dying elsewhere in the city. “We often say we’re happy to do it where we can find a location,” she said.

When introducing new tree species to supplement the urban canopy, they must be sure any newcomers won’t spread invasively — dominating their new habitats and causing damage to native species.

There are plenty of examples of what to avoid. The Norway maple, native to Europe and western Asia, has escaped the bounds of North American cities, creating excessive shade and crowding out understory plants — they’re one of the invasive species pushing out natives in the ravines of Toronto. Tree of heaven, native to China, deposits chemicals into the soil that damage nearby plants, letting it establish dense thickets and drive out native species; it is illegal to plant in parts of the U.S., including Indiana, where residents are urged to pull it up wherever they see it. The highly flammable eucalyptus, native to Australia, has put down roots all over the world, bringing increased wildfire danger along with it.

Urban tree experts don’t expect introduced species to cause major disruptions to native wildlife. Done right, adding some variety to cities dominated by one kind of tree could reduce the problems caused by waves of pests or disease. A patchwork of species could create a buffer against tree-to-tree infection among the same species. While it’s possible that new plant species displace plants used by animals that depend on one kind of plant to survive, those cases are the exception, Esperon-Rodriguez, the ecologist at Western Sydney University, said.

Some native animals do surprisingly well alongside their new plant neighbors. Introducing trees that are closely related to what’s already there could provide additional food and shelter for the local fauna. Animals might already be eating fruit from a new tree that grows somewhere else in their range.

If it thrives, my Howard McMinn manzanita could attract Anna’s hummingbird with its pale blossoms in the Pacific Northwest, just as it would in its native California hills.

For now, my manzanita is a small bush. (Manzanita straddles the line between shrub and tree, which is not a clear-cut distinction. The definition of a tree is something that ornithologist David Allen Sibley said “one could quibble endlessly over.”) The plant made it through a cold snap this winter, and I was happy to see the bright green new leaves growing at the tips of its little branches after temperatures warmed.

Eager for a sign of spring, I leaned in close and found what I was looking for: clusters of tiny, unopened flower buds.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline As the climate changes, cities scramble to find trees that will survive on Apr 24, 2024.

This coverage is made possible through a partnership with WABE and Grist, a nonprofit, independent media organization dedicated to telling stories of climate solutions and a just future.

In a case that could impact other lawsuits on voting rights, Black voters who sued over Georgia’s elections for key utility regulators are appealing their case to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Those elections for the Georgia Public Service Commission, or PSC, have been on hold for years and while last week a federal appeals court lifted an injunction blocking the elections from taking place, there is little chance the elections will happen this year.

Public Service Commissioners have enormous sway over greenhouse gas emissions because they approve how electric utilities get their power. They also set the rates consumers pay for electricity.

In Georgia, the commissioners have to live in specific districts. But unlike members of Congress who are only elected by residents of their district, the Georgia commissioners are elected by a statewide, at-large vote. A group of Black voters in Atlanta argued in a lawsuit that this violates Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act because it dilutes their votes, preventing them from sending the candidate of their choice to the commission.

In one example the plaintiffs cited, the former commissioner for District 3, which covers Metro Atlanta, “was elected to three terms on the PSC without ever winning a single county in District 3.”

That commissioner — along with four of the five current commissioners — is a white Republican. Georgia’s population is one-third Black, with a much higher proportion in District 3. Georgia voters elected Democrat Joe Biden and two Democratic U.S. Senators in 2020, and Atlanta voters tend to choose Democrats for seats ranging from mayor and city council to U.S. Congress.

A federal judge agreed with the plaintiffs in 2022 and suspended PSC elections until the state legislature could devise a new system. However, in November 2023, the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals reversed that decision.

The appeals court ruling took issue with the proposed fix of single-member district elections, arguing a federal court can’t overrule the state’s choice to hold at-large elections because it would violate the “principles of federalism.”

“It’s kind of an upside-down view,” said Bryan Sells, one of the lawyers for the plaintiffs. “What the 11th Circuit’s ruling says is that Georgia is allowed to discriminate against Black voters.”

The plaintiffs are asking the U.S. Supreme Court to overturn the appeals court decision, though there’s no guarantee the Supreme Court will take up the case.

In their petition for Supreme Court consideration, the plaintiffs argue that if it’s upheld, the appeals court decision “would upend decades of settled law and have a cascading effect far beyond the reach of this case.”

“[The appeals court panel] simply decided that whatever rationales Georgia might tender for the at-large scheme…automatically trump any amount of racial vote dilution, no matter how severe,” the petition argues. “If a State’s interest can prevail in this case, there is no case in which it won’t.”

The Georgia secretary of state’s office declined to comment on the appeal.

In the meantime, PSC elections have been on hold since 2022, when the federal judge who found for the plaintiffs imposed an injunction blocking the secretary of state from holding or certifying those elections. The 11th Circuit issued an order last week lifting the injunction, though its effect was not immediately clear.

Sells and a spokesman for the secretary of state’s office both said they were reviewing the order. In a text message, Sells also expressed surprise at what he called “the court’s unilateral action that no one asked for.”

Under the injunction, elections for two PSC seats that were scheduled for November 2022 were canceled. Despite not facing voters, those commissioners continue to serve and vote on PSC decisions, including rate increases and the three new fossil fuel-powered turbines the commission just approved.

PSC elections are also not on the 2024 ballot. A third commissioner’s term will expire at the end of the year.

A bill that passed the Georgia General Assembly before the Supreme Court appeal was filed or the injunction was lifted lays out a schedule for elections to resume, still following the current model of statewide voting. Governor Brian Kemp signed it into law last week.

The law schedules those elections to begin in 2025.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How should Georgia elect key utility regulators? US Supreme Court is asked to weigh in. on Apr 24, 2024.

This story is published as part of the Global Indigenous Affairs Desk, an Indigenous-led collaboration between Grist, High Country News, ICT, Mongabay, Native News Online, and APTN.

More than 20 years ago, the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, or UNPFII, held its annual meeting with a focus on youth, and educating and nurturing them. This year, the forum’s 24th gathering, the emphasis was again on youth — but this time on listening to them.

Meet seven of the young leaders who spoke at this year’s forum.

Name: Michael Severin Bro

Age: 32

Peoples: Inuit

Home: Ilulissat, a small town on the western coast of Greenland. His family calls him Mikaali.

What he wants people to know: Bro believes Indigenous and LGBTQ+ communities are especially vulnerable in Greenland.

“We have been struggling within society, and we need to be included in decision-making,” he said. “I refer to myself as Sipineq, which is our word in Inuit language defining everything about queerness, or all letters of the LGBTQIA+.”

Advocating for both issues is complicated. “It’s like wearing two hats,” he said.

More: As climate change warms the Arctic four times faster than global temperatures, Bro said that Greenland’s Inuit are facing difficulties in seal hunting.

Name: Gervais NdIhokubwayo

Age: 30

Peoples: Batwa

Home: Bujumbura, Burundi

What he wants people to know: Batwa children need more support for their education, including infrastructure and school supplies.

The Batwa are one of the oldest Indigenous cultures in Africa. In Burundi, they receive little support from the government. The Batwa in Uganda experience health disparities due to climate change.

More: The focus on youth at this year’s forum was exciting.

“Compared to last year, there’s a noticeable advancement in prioritizing youth perspectives, fostering collaboration, and advocating for Indigenous rights on a global scale,” he said.

Name: Kseniia Bolshakova

Age: 24

Peoples: Dolgan

Home: Popigai in Siberia, Russia

What she wants people to know: Her community in Siberia has difficulties getting access to fresh drinking water, because of colonization and climate change. Bolshakova would like to seek help to get a salination station near her village that converts sea water into fresh water.

“There is no funding for this,” she said through a translator. “This challenge is very costly and that’s why the problem has not been solved.”

She’s writing a book on language revitalization, and the effects of climate change on her homeland.

More: When she was still in Russia, she participated in a protest against the war in Ukraine. Afterward, she felt under threat and left the country, and believes it would be unsafe for her to return. She currently lives in New Hampshire.

Name: Jakirah Telfer

Age: 21

Peoples: Kaurna

Home: Aldelade, on the coast of southern Australia

What she wants people to know: She feels responsible for fixing climate change brought on by colonialism, but also powerless if Australia won’t listen to Aboriginal people. She started to cry in frustration during a panel discussion at the UNPFII, because she was reminded of her grandmother who was part of the Stolen Generation, a dark chapter in Australia’s colonial history when Aboriginal children were taken from their parents to be assimilated into colonial society.

“I sort of had to reflect, because I hated myself for crying. I think one thing the U.N. is missing is emotion and vulnerability,” she said. “I hated myself for crying, but I also felt so nurtured and safe in that space with so many other Indigenous peoples. I just feel like youth brings that passion.”

More: She thinks about her relationship with the land as a language.

“When we listen to the land, the land will listen to us. It’s a language. Climate change is creating a language barrier.”

Name: Nilla-Juhán Valkeapää

Age: 19

Peoples: Sámi

Home: Helsinki, Finland

What he wants people to know: Finland is forcing the Sámi Parliament to redo an election and include some 70 residents of the homeland who are not Sámi, a move that leaves Valkeapää concerned. The Sámi believe this is an infringement on their self-determination.

If the Sámi Parliament is treated with so little respect, then Valkeapää feels especially invisible because of his youth.

“People are like, ‘Youth are the future, listen to the youth.’ But when it comes to actually listening to us they are like, ‘Nah let the adults do this stuff,’” he said.

He is proud of being Sámi in Finland, so this recent infringement on the Sámi electoral process makes him nervous about the future. Especially after a recent U.N. report outlined that Finland still needs to do more to address the historical removal of the Sámi from their lands and suppression of their language.

More: Green energy projects have threatened the Sámi homeland over the last few years, including an illegal wind farm in Norway.

Name: Majo Andrade Cerda

Age: 29

Peoples: Kichwa

Home: Puyo, Ecuador

What she wants people to know: She’s an activist who wants to better protect the Amazon rainforest, a place very important to the Kichwa. While she believes there has been progress in getting more young people involved in the United Nations, she still sees barriers, especially with people for whom English is a second or third language.

“I recognize my privilege in being able to learn English, so if [member states] want to help, they would help with the language barrier,” she said.

More: Cerda is a member of Yuturi Warmi, the first Indigenous women guard that protects the Ecuadorian rainforest, and she is also a community organizer for Escuela Runa Yachay.

Name: Morgan Brings Plenty

Age: 29

Peoples: Cheyenne River Sioux

Home: Eagle Butte, South Dakota

What they want peolpe to know: Brings Plenty is two-spirit, an umbrella term that encompasses an array of Indigenous gender identities. An activist since they were 12, they are critical of the push for electric cars as a way to stop using fossil fuels, since few people think about the burden that puts on tribal lands through mining.

“People say ‘go green,’ but there are a lot of false solutions,” they said. “Like there’s electric cars, but you have to mine lithium.”

As an example, they point to the potential for lithium mines in the Black Hills of South Dakota, a sacred space for the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, Omaha, and many other tribes.

“[It] goes into the water and gets into Indigenous communities,” they said. “There are health concerns there,” they said.

More: Brings Plenty wanted to make sure their colleagues also got credit for their work at the U.N. — Annalee Yellowhammer, 20, and Maya Runnels, 22, from the Standing Rock Sioux tribe.

“We are a team. We are a group effort,” they said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline From Australia to the Arctic, young Indigenous changemakers speak out on Apr 24, 2024.

Grasslands — also known as savannas, prairies, steppes and pampas — are ecosystems found in parts of the world that do not get sufficient consistent rainfall to support forest growth, but get enough to avoid the landscape turning into desert. Often, grasslands are a transition ecosystem between deserts and forests.

Found on every continent other than Antarctica, grasslands are typically flat and open, making them more vulnerable to human development. Agriculture, overgrazing, drought, illegal hunting, invasive species and climate change are all threats to the health of grasslands and the wildlife who live in their abundant expanse.

Resilient and beneficial, grasslands and rangelands provide many essential ecosystem services such as acting as habitat for large mammals, burrowing animals, reptiles and pollinators; mitigating flooding and droughts; water filtration; and long-term carbon sequestration.

Even with all the benefits they provide, less than 10 percent of grasslands are protected globally.

Grasslands go by many different names and are made up of two main types: tropical — also known as savannas — and temperate.

The two types appear similar, but have different kinds of soil and are inhabited by a variety of unique creatures depending on their location. As many as 25 large plant-eating species can be supported by the different types of abundant grasses in any given grassland habitat.

African savannas are home to many iconic animal species, like elephants, lions, giraffes, gazelles, zebras, cheetahs and wildebeest.

The savannas of northern Australia, sub-Saharan Africa, Asia and South America are examples of tropical grasslands. The climate is warm with contrasting rainy and dry seasons. Savannas get most of their rainfall for the year in only a few months, which means trees are without water for long periods of time, inhibiting their growth.

The soil of savannas is not as rich as that of temperate grasslands. Rainfall can vary from year to year — 10 to 40 inches — and season to season. Temperatures are also highly variable, from below freezing to above 90 degrees Fahrenheit.

Vegetation height depends on the amount of rainfall a region gets. Some grasses can be less than a foot tall, while others may be up to seven feet high, with roots extending as deep as three to six feet. Two of the many types of grassland vegetation found in tropical savannas include Rhodes grass and red oat grass.

Because of their moderate rainfall and underground biomass, savanna soil tends to be extremely fertile and beneficial for crops.

Temperate prairies in the U.S. are lively with burrowing creatures such as prairie dogs and black footed ferrets, bison, deer, elk, pronghorns, coyotes, badgers and swift foxes, as well as bird species like larks, sparrows, raptors and blackbirds.

The rich soil of temperate grasslands means grasses are abundant and tall. Galleta and purple needlegrass — native to California — are two of the species found in the temperate grasslands of North America, Northern Mexico and Argentina.

Grassland habitats provide an abundant variety of grasses that wildlife use as a food source, for building burrows and nests and as camouflage from predators and prey.

Wildflowers like hyssop, yarrow and milkweed spring up and carpet grasslands during the rainy season, attracting pollinators that are important to crops and native vegetation. Grassland vegetation has adapted to the grazing, wildfires and drought that regularly occur in the ecosystem.

The deep root systems of prairie grasses absorb the abundant water that comes with the rainy season, reducing runoff, flooding and erosion. Wells made by roots trap water and act as sponges that slowly release the water into the soil. This ecosystem service is becoming increasingly important as extreme rainfall becomes more common due to climate change.

The deep roots of grassland vegetation also boost drought resistance, as they retain water longer than plants with shallow roots.

Though most seeds are deposited close to their parent, grassland plants use a variety of creative transport methods to spread their seeds far and wide through the process of seed dispersal. Whether they travel by wind, water or animal courrier, each seed has unique physical characteristics fit for the job.

Some seeds are contained inside fruits animals enjoy, and when they are ingested, the seeds travel with their host until they are deposited somewhere else.

Other plants, like violets, produce seed pods. When they are ripe, they pop open and eject the seeds away from the parent plant. Ants also bring violet seeds into their tunnels where they germinate.

The physiology of seeds like sandburs enables them to get caught on animals, who carry them to another location, sometimes a good distance away. Bison have historically been major seed carriers.

Wind is a common method of seed dispersal for prairie vegetation like milkweed, thistle, wild lettuce, goldenrod, aster and other plants that have little propellers or feathery or wing-like structures that catch the wind. Other seeds are so light and tiny that they are blown easily, like dust.

In moist prairies and wetlands, seeds that are able to float are dispersed by wind, rivers and streams.

Whatever the method, seed dispersal is an ingenious and efficient way for grassland plants to ensure at least some of their seeds have a chance of propagating.

Grasslands help filter and purify surface water, groundwater and air with their dense, deep roots, which trap rainwater, allowing it to trickle into the soil, where it is cleaned. This is especially important in agricultural areas where harmful chemicals are used. Some farmers plant buffers of grasses alongside ditches and streams to catch excess pesticides, phosphorus, nitrogen and sediment before it makes its way into freshwater sources.

Grassland vegetation cleans the air by removing carbon dioxide — turning it into energy and releasing oxygen as a byproduct through the process of photosynthesis. Plant roots also store carbon in the soil, rather than releasing it into the atmosphere.

In some areas, agricultural runoff contaminates soil, drinking water and groundwater with chemicals, polluted sediment, manure, bacteria and an overabundance of nitrites and nutrients.

Runoff also harms fish and other aquatic life. Grasslands’ carbon-rich soils and vegetation act as a natural filter of agricultural toxins, preventing them from entering waterways.

Roughly half a million tons of pesticides, four million tons of phosphorus and 12 million tons of nitrogen are applied each year to U.S. crops, pointing to the importance of intact grasslands to help maintain the country’s clean freshwater sources.

Temperate grasslands have dark soil rich in nutrients from their deep, many-branched roots. When vegetation rots, it binds soil together and provides food for living plants.

Savannas, on the other hand, have porous soil with a thin humus layer that drains water quickly.

In addition to the nutrients that come from decaying roots, the bulk of organic matter in grassland soils comes from animal manure. Only a small portion of the soil’s nutrients comes from plant matter.

The consistently rejuvenating process of growth, decay, nourishment and regrowth keeps grassland soils fresh and robust.

Grasslands’ extensive, deep root systems help to prevent erosion by anchoring soil and holding it in place.

The ability of grassland vegetation to increase water permeation and stimulate soil microbes contributes to improved soil structure and healthier soil overall, which means better plant growth.

The root systems of grasslands are denser and more shallow than those of woodlands and grow laterally, providing the best erosion control.

Grasslands provide a natural and sustainable form of “pest” control by providing food, breeding sites and shelter for species — like spiders and ground beetles — who consume them. These services are an alternative to the use of toxic chemicals on crops.

Pesticides meant to kill certain “pests” contaminate soil and water and can end up harming or killing pollinators, other insects and larger animals as well.

Expanding grasslands and other natural habitats like hedgerows and forests near agricultural lands — as well as establishing new ones — can help increase this regenerative form of “pest” management.

Not only do grasslands sequester a third of the planet’s carbon deep in their root systems and soil, the carbon is not released unless the ground is tilled or dug up. This means that — unlike trees that release their sequestered carbon when they die — undisturbed prairies and savannas are able to store carbon for thousands of years, even when their grasses are destroyed by wildfires.

Their remarkable ability to store carbon contributes to climate stability and helps fight climate change.

Wildfires can be beneficial to grassland ecosystems and play an important role in keeping grasslands healthy by helping to prevent woody shrubs, trees and invasive species from taking over the landscape. This helps increase wildflower diversity, which in turn supports pollinators.

Wildfires help maintain vegetation habitat for species that need open, sunny conditions to germinate, like wildflowers and oak trees. Fresh habitat is created after a fire, which sometimes attracts new species, but can also lead to a decline in others.

Native Americans help maintain grasslands for bison and other species by setting fires. The grazing animals enjoy the fresh grass regrowth in that area and graze on it more frequently.

The rich soil of temperate grasslands have led to most in the U.S. being converted into farm or grazing land. The loss of so much grassland has destroyed wildlife habitat, affecting many species, including vital pollinators who depend on grassland wildflowers for food. This in turn affects crops and native flowers, which rely on the pollinators for propagation.

Along with agriculture comes increased sedimentation, soil erosion, pesticides, livestock manure and nutrient runoff, which leaches into groundwater, rivers and streams.

Drought can have a major impact on grasslands, reducing the productivity of vegetation and causing massive plant dieoff that can limit species’ geographical distribution.

Native grasslands have evolved to adapt to low levels of precipitation, but unusually severe and prolonged drought is a different story. It can reduce plant abundance and affect the amount of forage vegetation for grazing animals.

Drought and overgrazing during rapid growth periods of a plant’s life also lead to less growth the following year. And when drought and high temperatures cause the green leaf area of plants to be removed, or lack of soil moisture limits the production of carbohydrates, plant growth can be delayed or reduced.

The effects of severe drought are predicted to occur more frequently due to climate change. A 2024 study found that the loss of plant growth was 60 percent higher during extreme short-term droughts when compared with historically more common droughts that are less severe.

Overgrazing is a main contributor to degradation of grasslands worldwide. It reduces vegetation cover and degrades topsoil, leading to soil compaction from trampling by wildlife. It also increases soil susceptibility to erosion and reduces infiltration rates.

One of the best ways to ensure grasslands do not become degraded is to support sustainable grazing. Grazing management works best when it takes into account the characteristics of the local environment, as well as factors like elevation, slope, water accessibility and climate.

Reducing the grassland ecosystem’s competitive nature through selective grazing can help thin out some plants while allowing others to become more dense.

Invasive plant species can reduce grassland quality and displace native plants. These non-native grasses may not be able to withstand extreme weather such as wildfires and drought, leading to further loss of habitat.

Illegal hunting has decimated many large animal populations, affecting entire ecosystems. Large animals like elephants crush and eat shrubs and trees, preventing them from overtaking grasses and turning savannas into forests.

Loss of grasses means less vegetation for grazing animals such as the endangered Grevy’s zebra.

As global heating affects Earth’s rainfall patterns, marginal grasslands can turn into deserts.

Additionally, increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere affects the cycle of water, carbon and nitrogen, which controls the exchange of air and gasses in plants — particularly grassland vegetation. When carbon concentrations are higher, plant stomata get smaller in order to save water, reducing transpiration. When this happens, the flow from soil to roots and leaves is also reduced, potentially lowering nitrogen uptake and weakening plants’ ability to perform photosynthesis.

Education is essential to restoring and conserving grassland habitats for wildlife, essential carbon storage and the many other ecosystem services grasslands provide. Educating farmers and the public about how important grasslands are to the planet — as well as about methods to build and protect healthy, chemical-free soil — will help safeguard these vital ecosystems for the future.

Crop rotation is a key part of building and maintaining healthy soil, as greater plant diversity means more accumulation of organic matter and nutrients, which improves productivity. It can also disrupt the life cycles of “pests,” thereby acting as a natural substitute for toxic pesticides.

Not only do we need to protect and restore grasslands, but we need to safeguard wetlands — a crucial part of grassland ecology — at the same time.

Setting aside more of Earth’s terrestrial habitat for nature is one of the most important ways to help protect grasslands. The creation of nature reserves and state and national parks, the enforcing and expansion of endangered species protections and the repurposing of land and land restoration can all work together to preserve and restore natural ecosystems like grasslands. This serves to enhance biodiversity, conserve soils and vegetation and mitigate the impacts of climate change.

It is also important to increase investment in key conservation programs to keep grasslands healthy and intact. We must preserve old-growth grasslands through easements and acquisition.

Grasslands can be restored through the thinning of forested areas that were once open. In addition, controlled burning can stimulate vegetation growth while replenishing calcium stored in dried grasses to the soil.

Biodiversity research is essential to understand the complexity of grassland ecosystems so that we can better protect and restore them for future generations. Planning for the future by seedbanking ensures we continue to have the “right seed” when we need it to reestablish grasslands that are at risk of extinction.

One of the best ways to help preserve our grasslands is to volunteer with a restoration organization. Citizen science projects like vegetation and soil collection and wildlife monitoring can help researchers to better understand these important ecosystems.

You can support legislation that promotes the sustainable use of land, prevents deforestation and looks after biodiversity in your area.

Opting for sustainable methods of gardening, reducing personal consumption and choosing products from companies that use eco-friendly practices are all ways to support grasslands and the environment as a whole.

Supporting the rights and traditional knowledge of Indigenous Peoples whose stewardship of the land has been sustainable for thousands of years is another important aspect of grassland conservation.

Other ways to help grasslands are to participate in activities like local educational programs, habitat restoration and clean up efforts. Bring friends and family along with you!

Grasslands are vitally important for biodiversity, nature and climate. They are essential habitat for billions of animals — such as the African elephant, long-billed curlew and black-footed ferret — throughout the world. They store roughly a third of the Earth’s carbon while providing climate resilience against heat waves, drought and wildfires. They are crucial for the food security, energy and livelihoods of many communities throughout the planet.

Despite their importance, grasslands are remarkably unprotected. From 2016 to 2020, 10 million acres of Great Plains grasslands were destroyed — mostly for crop agriculture. The destruction of grassland habitats is one of the main contributors to the steep decline of grassland birds, more than 300 species of which call the ecosystem home.

Grasslands provide natural solutions for carbon sequestration while reducing climate change impacts. Restoring and protecting them not only bolsters habitat and improves landscape resilience, it supports wildlife, rural and Indigenous communities and the ecological balance of the planet as a whole.

The post Grasslands 101: Everything You Need to Know appeared first on EcoWatch.